Key Findings

- State taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. changes are not made in a vacuum. States often adopt policies after watching peers address similar issues. Several notable trends in tax policy have emerged across states in recent years, and policymakers can benefit from taking note of these developments.

- The enactment of the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in late 2017 expanded many states’ tax bases and drove deliberations on tax conformity. By the end of 2019, all but four states with individual or corporate income taxes (or, in the case of Texas, a gross receipts taxGross receipts taxes are applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like compensation, costs of goods sold, and overhead costs. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and applies to transactions at every stage of the production process, leading to tax pyramiding. that relies on federal definitions) updated their conformity date to reflect a post-TCJA version of the Internal Revenue Code.

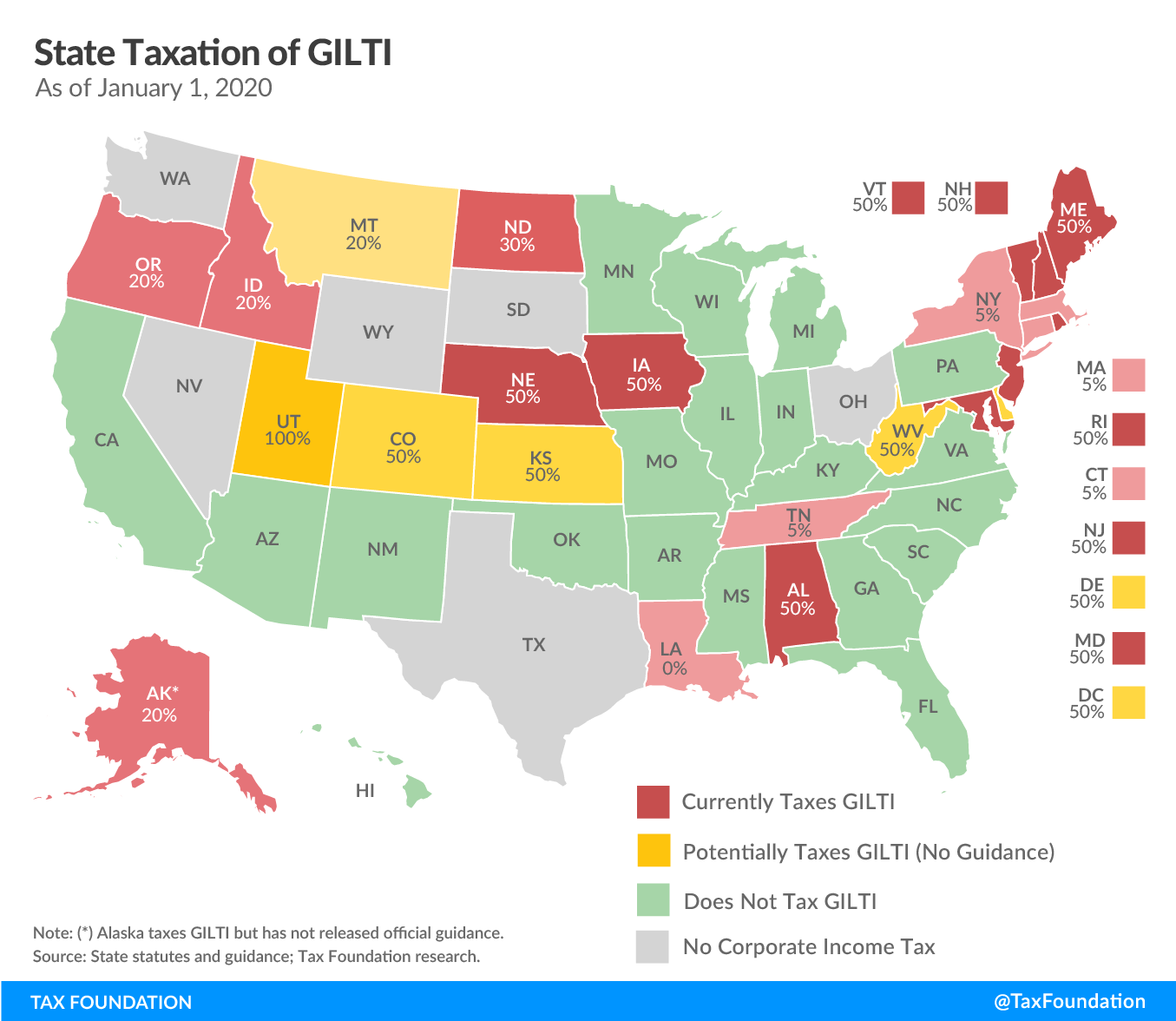

- Many states incorporate the new federal tax on Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) by default, which often positions them to meaningfully tax international income for the first time and, in many cases, raises serious constitutional questions. In 2018, few states had issued guidance on their approach to GILTI, but by the end of 2019, 17 states taxed GILTI and had issued guidance to that effect, and another seven states and the District of Columbia may tax GILTI but have yet to offer guidance to taxpayers.

- Five states cut corporate income taxes in 2019, and another two have reductions effective on, or which will be backdated to, January 1, 2020.

- Six states cut individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. rates in 2019, three of them retroactive to 2018 and designed as a response to the base-broadening provisions of the TCJA.

- The U.S. Supreme Court’s Wayfair v. South Dakota decision ushered in a new era of sales taxes on e-commerce and other remote sales, with 43 of the 45 states with state sales taxes implementing a remote seller regime by the end of 2019, though state legislation on marketplace facilitators remains a work in progress, with amendments likely in many states.

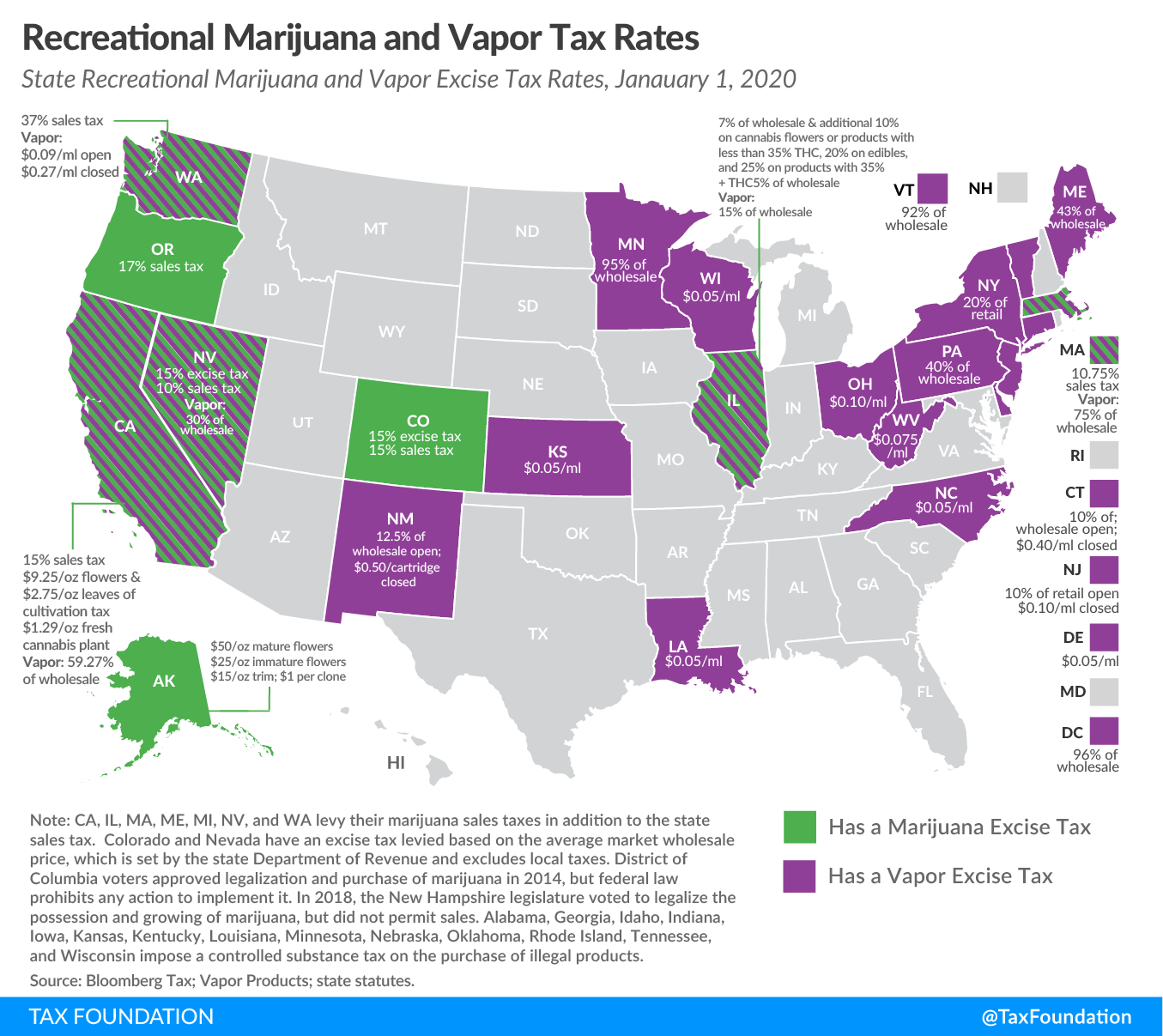

- Illinois was the only state to adopt legislation legalizing and taxing marijuana in 2019, but despite a slowdown, 2020 is shaping up to be a significant year, with some states exploring coordinated legalization efforts.

- A 2018 court ruling has states scrambling to legalize and tax sports betting, and eight states did so in 2019, joining 12 other states and the District of Columbia which already have active sports betting markets. The new rates range from 6.75 percent of gross revenues in Iowa to 51 percent in a monopolistic franchise system in New Hampshire.

- Another 11 states implemented excise taxes on vaping in 2019, as states continue to split on their approach to vapor taxation—specific excise or ad valorem

- After decades of ignoring a gradual erosion of gas taxes, states are now taking adjustments seriously, with four states adopting new rates in 2019 and a growing number of states using inflation indexingInflation indexing refers to automatic cost-of-living adjustments built into tax provisions to keep pace with inflation. Absent these adjustments, income taxes are subject to “bracket creep” and stealth increases on taxpayers, while excise taxes are vulnerable to erosion as taxes expressed in marginal dollars, rather than rates, slowly lose value. .

- States continue to raise the exemption thresholds for their estate taxes following the repeal of two estate taxes in 2018, continuing a decade-long trend away from taxes on estates and inheritances.

- Declining revenues from oil, gas, and other natural resources are forcing energy-rich states to scrutinize their tax codes and, in some cases, contemplate new taxes.

- Policymakers would do well to pay attention to the experiences of their peers—to learn from their mistakes as well as their successes.

Introduction

The dawning of a decade instills a sense of newness and possibility, and perhaps anxiety, but whatever else may be in doubt, things as certain as death and taxes can be more firmly believed.[1] The new decade will have its share of new ideas and challenges—the state taxation of international income, for instance, or of remote sales or even of sports betting—but also more than its fill of old ones. And even the “new” draw from the old, for what’s past is prologue, now as always.

State tax policy decisions are not made in isolation. Changes in federal law, global markets, and other exogenous factors create a similar set of opportunities and challenges across states. The challenges faced by one state often bedevil others as well, and the proposals percolating in one state capitol often show up elsewhere. Ideas spread and policies can build their own momentum. Sometimes a trend emerges because one state consciously follows another, and in other cases, similar conditions result in multiple states trying to solve the same problem independently.

Identifying state tax trends serves a dual purpose: first, as a leading indicator providing a sense of what we can expect in the coming months and years, and second, as a set of case studies, placing ideas into greater circulation and allowing empirical consideration of what has and has not worked. Policymakers across the country can benefit from a greater awareness of these trends.

Four key developments underlie many tax trends from 2019, some of them continuing from prior years. First, the adoption of the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) continues to reverberate through state tax codes, particularly in the realm of international taxation. Second, the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2018 decision in Wayfair v. South Dakota is still playing out in state capitols as lawmakers tinker with their newly empowered remote seller and marketplace facilitator sales and use tax regimes. Third, expanding legal markets in gaming, marijuana, and vapor products provide new avenues for excise taxation. And fourth, changes roiling the energy sector are showing up in the budgets of states heavily reliant on extractive industries, with potential consequences for state taxation.

Income Taxes

Across the country, income tax policies—both individual and corporate—were heavily influenced by the enactment of federal tax reform. States grappled with how to conform to the provisions of the new tax law, and in some cases sought to help their taxpayers circumvent its effects. The past year saw reductions in individual and corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rates and the adoption of further reforms intended to enhance the neutrality of individual income tax codes.

IRC Conformity Updates

Most states begin their own income tax calculations with federal definitions of adjusted gross income (AGI) or taxable income, and they frequently incorporate many federal tax provisions into their own codes. The degree to which state tax provisions conform to the federal Internal Revenue Code (IRC) varies, as does the version of that code to which they conform. Some states have “rolling conformity,” meaning that they couple to the current version of the IRC, while others have “static conformity,” utilizing the IRC as it existed at some fixed date. Although exceptions exist, most states with static conformity update their conformity date every year as a matter of course.

The adoption of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act turned what had been routine into a serious policy deliberation. Most states stand to see increased revenue due to federal tax reform, with expansions of the tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. reflected in state tax systems while corresponding rate reductions fail to flow down. The increase in the standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. It was nearly doubled for all classes of filers by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) as an incentive for taxpayers not to itemize deductions when filing their federal income taxes. , the repeal of the personal exemption, the creation of a deduction for qualified pass-through businessA pass-through business is a sole proprietorship, partnership, or S corporation that is not subject to the corporate income tax; instead, this business reports its income on the individual income tax returns of the owners and is taxed at individual income tax rates. income, the narrowing of the interest deduction, the cap on the state and local tax deductionA tax deduction allows taxpayers to subtract certain deductible expenses and other items to reduce how much of their income is taxed, which reduces how much tax they owe. For individuals, some deductions are available to all taxpayers, while others are reserved only for taxpayers who itemize. For businesses, most business expenses are fully and immediately deductible in the year they occur, but others, particularly for capital investment and research and development (R&D), must be deducted over time. (which affects state deductions for local property taxes), adjustments to the treatment of net operating losses, and enhanced cost recoveryCost recovery is the ability of businesses to recover (deduct) the costs of their investments. It plays an important role in defining a business’ tax base and can impact investment decisions. When businesses cannot fully deduct capital expenditures, they spend less on capital, which reduces worker’s productivity and wages. for machinery and equipment purchases, and even some of the provisions on the taxation of international income, flow through to the tax codes of some states—in different combinations, depending on the federal code sections to which they are coupled.[2]

States, therefore, were faced with choices. They could continue to conform to an older version of the IRC to avoid these revenue implications.[3] Alternatively, if conforming to the IRC post-TCJA, they could decouple from revenue-raising provisions, cut tax rates or implement other tax reforms to offset revenue increases, or do nothing, keeping the additional revenue.

At the conclusion of 2018, 32 states and the District of Columbia conformed to a version of the IRC which includes the reforms adopted under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. By the end of 2019, all but four states with individual or corporate income taxes (or, in one case, a gross receipts tax that uses IRC definitions) conformed to a post-TCJA version of the IRC. The remaining outliers are California, Massachusetts (for individual income taxes only), New Hampshire, and Texas (for its gross receipts tax).[4]

Entering 2020, 21 states and the District of Columbia use rolling conformity for both their individual and corporate income taxes, while two states—Massachusetts and Pennsylvania—employ rolling conformity exclusively for their corporate income taxes. Another 15 states use static conformity for both taxes, while the remaining states with income taxes use selective conformity, defining most major tax provisions independently of the federal tax code.[5]

Addressing the Taxation of International Income

Historically, federal taxes extended to international income, with credits for taxes paid to other countries. If the U.S. rate was higher than the rate in the country where income was earned, taxpayers remitted the difference to the Internal Revenue Service. State tax codes, by contrast, generally did not reach beyond the “water’s edge”—or at least, only did so on a very limited basis. One of the great ironies of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act is that a law intended to pull the federal government back from the taxation of international income has become a vehicle for states to expand significantly into that realm for the first time.

With the U.S. now operating on a quasi-territorial tax code, guardrails were established to curtail profit shifting by placing intangibles like patents or trademarks in low-tax countries. One of these, the tax on Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI), automatically flows through to the tax code of many states unless they intentionally decouple or make an administrative determination that GILTI qualifies for existing deductions for foreign dividend income. Consequently, while the federal government is trying to get out of the business of taxing international income (more or less), some states are moving in the opposite direction.

State tax codes, however, were not designed with international income in mind, nor is there a compelling reason why the income of foreign subsidiaries (controlled foreign corporations) should be taxable in a U.S. state. Bringing all this international income into a state’s tax base, moreover, can drastically expand corporate income tax liability for firms headquartered in a given state, undercutting a state’s business competitiveness. Finally, depending on how states tax GILTI, they risk long and costly litigation. In many states, there is no provision for the fair apportionment of GILTI in the state tax code, leading to its overinclusion, and in states which adopt separate rather than combined reporting (meaning that they do not normally tax all related companies as a single entity), a difference in treatment between international and U.S.-based subsidiaries raises additional constitutional issues.

For these and other reasons, states have been slow to issue guidance on if and how they tax GILTI, even two years after enactment of the TCJA. In 2019, however, that dam began to break, and additional activity should be anticipated in 2020. More states will issue guidance on how much, if any, GILTI is included in the tax base and how it is apportioned. As policymakers become more familiar with the issue, new legislation either decoupling or limiting GILTI is likely, and it is also plausible that the first serious round of litigation will commence in states that overreach.

Entering 2019, few states had outlined their approach to GILTI taxation. By year’s end, 17 states taxed GILTI and had guidance to that effect, leaving seven remaining states and the District of Columbia that might hypothetically tax GILTI based on their tax definitions, but where guidance is not yet forthcoming. Every state taxing GILTI incorporates some sort of deduction, most commonly following the federal government in providing a 50 percent deduction under IRC § 250, often in tandem with a dividends received deduction (DRD) worth 80 to 100 percent of the inclusion. Consequently, nine states include 50 percent of GILTI (the § 250 deduction only) and eight include amounts ranging from 5 to 30 percent, though proper factor representation is still largely lacking.

|

(a) Separate reporting state, raising constitutional issues because U.S.-based out-of-state subsidiaries are treated differently than international subsidiaries (controlled foreign corporations). (b) State has not conformed to the IRC post-TCJA, but could include GILTI with update. (c) The deduction is reduced to 80 percent if the taxpayer elects not to submit domestic disclosure spreadsheets. (d) A 70 percent deduction for foreign dividends is available for companies filing returns using the water’s edge method, while GILTI is eliminated (100 percent deduction) as duplicative for companies using a worldwide combined reporting method. n.a.: Not applicable. Sources: State statutes and guidance; Tax Foundation research. |

|||||

| State | Inclusion | In Starting Point | § 250 | DRD | Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama (a) | 50% | Yes | Yes | 0% | ✓ |

| Alaska | 20% | Yes | No | 80% | ✗ |

| Arizona | 0% | No | No | 100% | |

| Arkansas | 0% | No | No | 100% | |

| California | 0% | No (b) | No | 0% | |

| Colorado | 50% | Yes | Yes | 0% | ✗ |

| Connecticut | 5% | Yes | No | 95% | ✓ |

| Delaware (a) | 50% | Yes | Yes | 0% | ✗ |

| Florida | 0% | No | No | 100% | |

| Georgia | 0% | No | Yes | 100% | |

| Hawaii | 0% | No | No | 100% | |

| Idaho (c) | 15% | Yes | Yes | 85% | ✓ |

| Illinois | 0% | No | No | 100% | |

| Indiana | 0% | No | No | 100% | |

| Iowa (a) | 50% | Yes | Yes | 0% | ✓ |

| Kansas | 50% | Yes | Yes | 0% | ✗ |

| Kentucky | 0% | No | No | 100% | |

| Louisiana | 0% | Yes | Yes | 100% | ✓ |

| Maine | 50% | Yes | No | 0% | ✓ |

| Maryland (a) | 50% | Yes | Yes | 0% | ✓ |

| Massachusetts | 5% | Yes | No | 95% | ✓ |

| Michigan | 0% | No | Yes | 100% | |

| Minnesota | 0% | No | No | 100% | |

| Mississippi | 0% | No | No | 100% | |

| Missouri | 0% | No | Yes | 100% | |

| Montana | 20% | Yes | No | 80% | ✗ |

| Nebraska | 50% | Yes | Yes | 0% | ✓ |

| Nevada | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| New Hampshire | 50% | Yes | Yes | 0% | ✓ |

| New Jersey | 50% | Yes | Yes | 0% | ✓ |

| New Mexico | 0% | No | Yes | 100% | |

| New York | 5% | Yes | No | 0% | ✓ |

| North Carolina | 0% | No | No | 100% | |

| North Dakota (d) | 30% | Yes | No | 70% | ✓ |

| Ohio | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Oklahoma | 0% | Yes | No | 100% | |

| Oregon | 20% | Yes | No | 80% | ✓ |

| Pennsylvania | 0% | No | No | 100% | |

| Rhode Island | 50% | Yes | No | 0% | ✓ |

| South Carolina | 0% | No | No | 100% | |

| South Dakota | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| Tennessee | 5% | Yes | Yes | 95% | ✓ |

| Texas | 0% | No (b) | No | 0% | |

| Utah | 100% | Yes | No | 0% | ✗ |

| Vermont | 50% | Yes | Yes | 0% | ✓ |

| Virginia | 0% | No | Yes | 100% | |

| Washington | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| West Virginia | 50% | Yes | Yes | 0% | ✗ |

| Wisconsin | 0% | No | No | 100% | |

| Wyoming | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| District of Columbia | 50% | Yes | Yes | 0% | ✗ |

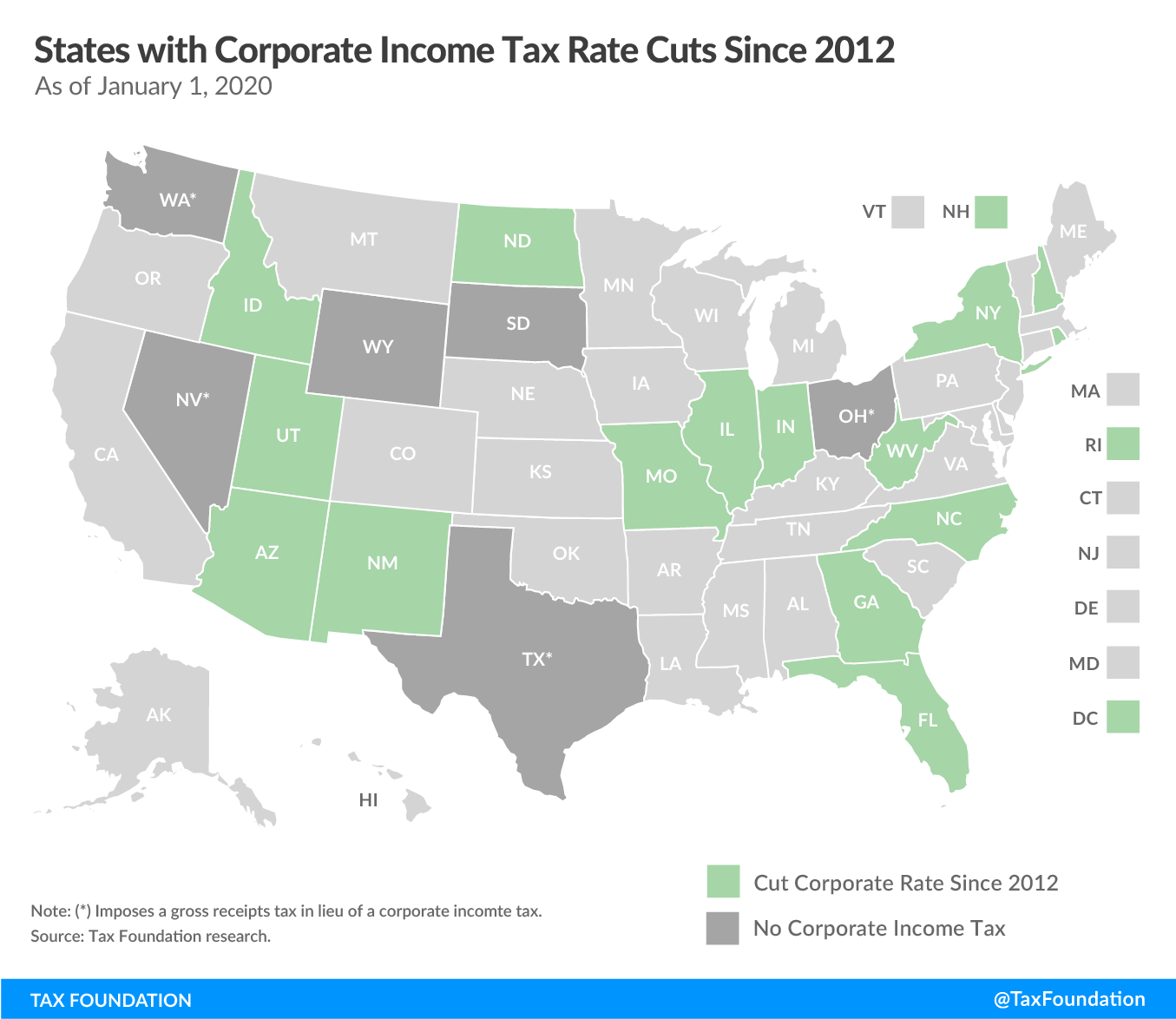

Corporate Income Tax Rate Reductions

Corporate income taxes represent a small and shrinking share of state revenue, the product of a long-term trend away from C corporations as a business entity and ever-narrowing bases due to the accumulation of tax preferences. (The pass-through sector has grown dramatically, both in raw numbers and share of business income, over the past few decades, due in no small part to the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which lowered the top individual income tax rate from 50 to 28 percent.[6]) Fifteen states and the District of Columbia have cut corporate taxes since 2012, including five in 2019 and two others effective on or retroactive to January 1, 2020.

In 2019, Georgia cut its corporate rate from 6.0 to 5.75 percent, the first of two planned reductions in response to the base-broadening provisions of the TCJA.[7] With little fanfare, Florida met a previously-established tax trigger in September and reduced its corporate income and franchise tax rate from 5.5 to 4.458 percent, retroactive to January 1, 2019.[8]

Indiana continued a series of rate reductions that began in 2011, reducing its rate from 5.75 to 5.5 percent; based on 2014 legislation, it is currently slated to continue a phasedown to 4.9 percent. New Hampshire, which has two statewide business taxes (the business profits tax, the state’s corporate income tax, and the business enterprise tax, a kind of value-added tax), reduced both rates in 2019, from 7.9 to 7.7 and 0.675 to 0.6 percent respectively. North Carolina trimmed its corporate income tax yet again, from 3.0 to 2.5 percent, the nation’s lowest corporate income tax rate, as revenues continue to meet or exceed projections.[9]

Several states, moreover, have already implemented rate cuts in 2020. In Missouri, the corporate income tax rate declined from 6.25 to 4.0 percent as of January 1 as the state switched to single sales factor apportionmentApportionment is the determination of the percentage of a business’ profits subject to a given jurisdiction’s corporate income or other business taxes. U.S. states apportion business profits based on some combination of the percentage of company property, payroll, and sales located within their borders. for most corporations, eliminating the choice of apportionment factor that existed previously.[10] A tax reform package adopted in December 2019 will see Utah’s corporate income tax rate reduced from 4.95 to 4.66 percent, a rate which will go into effect in February 2020 retroactive to the start of the year.[11] In July, Indiana’s corporate income tax rate will be cut again, to 5.25 percent.[12]

Although few states have repealed their corporate income taxes, their volatility, narrowing bases, economic impacts, and modest contribution to state revenues have all contributed to states’ decisions to reduce reliance on the tax.

|

Source: Tax Foundation research |

|||

| State | 2012 | 2020 | Scheduled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | 6.968% | 4.9% | — |

| Florida | 5.5% | 4.458% | |

| Georgia | 6.0% | 5.75% | 5.5% |

| Idaho | 7.6% | 7.4% | — |

| Illinois | 9.5% | 7.75% | — |

| Indiana | 8.5% | 5.5% | 4.9% |

| Missouri | 6.25% | 4.0% | — |

| New Hampshire | 8.5% | 7.7% | — |

| New Mexico | 7.6% | 5.9% | — |

| New York | 7.1% | 6.5% | — |

| North Carolina | 6.9% | 2.5% | — |

| North Dakota | 5.2% | 4.31% | — |

| Rhode Island | 9.0% | 7.0% | — |

| Utah | 5.0% | 4.95% | 4.66% |

| West Virginia | 7.75% | 6.5% | — |

| District of Columbia | 9.975% | 8.25% | — |

Individual Income Tax Rate Cuts

Continued state responses to the TCJA have increased the pace at which states have cut individual income taxes, with six states cutting rates in 2019 (three retroactive to 2018) and another two doing so effective January 1, 2020. (Two states, Arkansas and Massachusetts, saw rate cuts both years.)

Arkansas is the only state with multiple independent rate schedules depending on the filer’s taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. , with filers shifting schedules—and not just facing higher marginal rates—as their income rises. As part of a broader tax reform package, the top rate for the lowest schedule (for incomes under $21,000) declined from 4.4 to 3.4 percent, with lower brackets seeing rate reductions as well.[13] On January 1, 2020, further rate cuts took effect, with the top marginal rate declining from 6.9 to 6.6 percent.[14]

Georgia cut its individual income tax from 6.0 to 5.75 percent in tandem with its corporate income tax rate reduction, and three states—Idaho, Utah, and Vermont—cut individual income tax rates in 2019 but retroactive to 2018 in response to base broadeningBase broadening is the expansion of the amount of economic activity subject to tax, usually by eliminating exemptions, exclusions, deductions, credits, and other preferences. Narrow tax bases are non-neutral, favoring one product or industry over another, and can undermine revenue stability. under federal tax reform. Massachusetts continues to phase in rate reductions subject to revenue availability, trimming the rate from 5.15 to 5.1 in 2019 and cutting it further to 5.05 percent in 2020.[15]

Many other states have also seen additional revenue from the TCJA that could facilitate rate cuts, though the further removed from federal tax reform, the less likely that states will predicate additional income tax rate reductions on revenue they have already added to their baselines.

Sales and Excise Taxes

After the Wayfair decision, states moved quickly to impose collection and remittance obligations on remote sellers previously out of reach, and to create marketplace facilitator regimes requiring certain platforms to collect on behalf of their sellers. Meanwhile, shifting public attitudes, a changing legal environment, and product innovations are responsible for a spate of new or revised “sin” taxes on marijuana, sports betting, and vapor products, a trend likely to continue in coming years. Many states also adopted gas tax increases in 2019.

Revising Remote Sales Tax Standards

E-commerce represented 11.2 percent of all retail sales in the third quarter of 2019,[16] a slice of the retail pie that states are increasingly able to capture in the aftermath of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Wayfair v. South Dakota, which struck down the physical presence requirement for substantial nexus.[17] For the most part, states spent 2018 adopting new post-Wayfair remote seller laws, with companion laws imposing similar obligations on marketplace facilitators—platforms like Amazon Marketplace, eBay, or even UberEats—coming into their own in 2019. The year closed out with 43 of the 45 states with statewide sales taxes implementing collection and remittance obligations for remote sellers, and 38 states having provisions targeted at marketplace facilitator regimes.

This is, however, only the beginning of states’ responses to Wayfair, not the end. Policy and legal uncertainties continue to plague marketplace facilitator regimes, which vary substantially across states, and a few states are still grappling with policy solutions to make their sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. regimes Wayfair-compliant.

At year’s end, both the Multistate Tax Commission (MTC) and the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) were heavily engaged on the policy development front, with the MTC issuing a new white paper on the design and implementation of marketplace facilitator laws and related regulations, and NCSL still working on model legislation. Most states have a law in place, but the administration of those facilitator regimes, and possibly the text of the laws themselves, remain very much in flux. This is especially important because, early on, some states adopted extremely broad, vague definitions of what constitutes a marketplace facilitator—definitions that generate uncertainty and, if applied expansively, could lead to double taxation and other undesirable consequences.

|

Sources: State statutes; regulations and guidance; Tax Foundation research. |

||

| State | Remote Seller | Marketplace Facilitator |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 10/1/2018 | 1/1/2019 |

| Alaska | No state sales tax | |

| Arizona | 9/30/2019 | 10/1/2019 |

| Arkansas | 7/1/2019 | 7/1/2019 |

| California | 4/1/2019 | 10/1/2019 |

| Colorado | 6/1/2019 | 10/1/2019 |

| Connecticut | 7/1/2019 | 12/1/2018 |

| Delaware | No sales tax | |

| Florida | n.a. | n.a. |

| Georgia | 1/1/2019 | n.a. |

| Hawaii | 7/1/2018 | 1/1/2020 |

| Idaho | 6/1/2019 | 6/1/2019 |

| Illinois | 10/1/2018 | 1/1/2020 |

| Indiana | 10/1/2018 | 7/1/2019 |

| Iowa | 7/1/2019 | 7/1/2019 |

| Kansas | 10/1/2019 | 10/1/2019 |

| Kentucky | 10/1/2018 | 7/1/2019 |

| Louisiana | 7/1/2020 | n.a. |

| Maine | 7/1/2018 | 10/1/2019 |

| Maryland | 10/1/2018 | 10/1/2019 |

| Massachusetts | 10/1/2019 | 10/1/2019 |

| Michigan | 10/1/2018 | n.a. |

| Minnesota | 10/1/2019 | 10/1/2019 |

| Mississippi | 9/1/2018 | n.a. |

| Missouri | n.a. | n.a. |

| Montana | No sales tax | |

| Nebraska | 1/1/2019 | 4/1/2019 |

| Nevada | 10/1/2018 | 10/1/2019 |

| New Hampshire | No sales tax | |

| New Jersey | 11/1/2018 | 11/1/2018 |

| New Mexico | 7/1/2019 | 7/1/2019 |

| New York | 6/21/2018 | 6/1/2019 |

| North Carolina | 11/1/2018 | |

| North Dakota | 10/1/2018 | 7/1/2019 |

| Ohio | 8/1/2019 | 8/1/2019 |

| Oklahoma | 11/1/2019 | 11/1/2019 |

| Oregon | No sales tax | |

| Pennsylvania | 7/1/2019 | 7/1/2019 |

| Rhode Island | 8/17/2017 | 7/1/2019 |

| South Carolina | 11/1/2018 | 4/26/2019 |

| South Dakota | 11/1/2018 | 3/1/2019 |

| Tennessee | 7/1/2019 | n.a. |

| Texas | 10/1/2019 | 10/1/2019 |

| Utah | 1/1/2019 | 10/1/2019 |

| Vermont | 7/1/2018 | 6/1/2019 |

| Virginia | 7/1/2019 | 7/1/2019 |

| Washington | 10/1/2018 | 10/1/2018 |

| West Virginia | 1/1/2019 | 7/1/2019 |

| Wisconsin | 10/1/2018 | 1/1/2020 |

| Wyoming | 2/1/2019 | 7/1/2019 |

| District of Columbia | 1/1/2019 | 1/1/2019 |

Although the Wayfair decision eliminated the physical presence requirement, it did not bless all possible alternatives. States must still abide by existing Due Process and Commerce Clause constraints in designing their remote sales tax regimes, and most have elected to be guided in this process by the tax simplification provisions commended in the Wayfair decision—what we and others have termed the “Wayfair Checklist.”[18] The factors present in the challenged South Dakota law, which the Supreme Court strongly suggested would protect it against any further legal challenges, include:

- A safe harbor for those only transacting limited business in the state;

- An absence of retroactive collection;

- Single state-level administration of all sales taxes in the state;

- Uniform definitions of goods and services;

- A simplified tax rate structure;

- The availability of sales tax administration software; and

- Immunity from errors derived from relying on such software.[19]

Most states comply with the majority of these factors, with participants in the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement (SSUTA) faring best, because they all use common definitions, share sales tax administration software with immunity for any errors it might contain, and, as a condition of membership, have centralized state administration of all state and local sales taxes and use a unitary base across all jurisdictions. Regardless of SSUTA status, however, all states except Kansas have adopted a safe harbor for small sellers, though parameters vary. The absence of a de minimis exemption for smaller remote sellers can create constitutionally undue burdens.

A few states, most notably Alabama, Colorado, and Louisiana, face serious impediments to legal collection of remote sales tax—at least the local share—due to the breadth of local tax authority and the consequent lack of uniformity (with attendant high compliance costs for remote sellers). Simplification regimes adopted in Alabama and Louisiana face uncertain legal futures. Kansas’ lack of a safe harbor also raises serious constitutional concerns. These issues deserve to be resolved at the earliest opportunity. Some states should also view 2020 as an opportunity to clear out the detritus of the old physical presence regime, eliminating “click-through nexus,” “cookie nexus,” and notice and reporting requirements—creative, if complex and sometimes legally dubious, ways of expanding the pool of sales tax collectors in the days before Wayfair permitted the use of economic nexus standards.

In most states, however, 2020 is likely to be a year of tinkering and building out: adjusting definitions of marketplace facilitators in both regulation and statute, and enhancing, or providing for the first time, software solutions for remote sellers. That much of this will take place under the radar does not lessen its importance. This is a new field of state taxation, and early adopters lacked the benefit of subsequent deliberation and legal analysis. Policymakers would do well to take advantage of recent policy developments and legal analysis and to amend their remote seller and marketplace facilitator laws, where necessary, to ensure that they are consistent with the proper aims of this extension of state sales taxes: a broader, equitable, more stable, and legally resilient sales tax base that can serve states and their residents well for decades to come.

|

Sources: State statutes; guidance; Tax Foundation research. |

||

| State | Old Nexus Regime(s) Still on the Books | Facilitator Law Breadth |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | Notice and Reporting | Broad |

| Alaska | n.a. | |

| Arizona | Narrow | |

| Arkansas | Narrow | |

| California | Broad | |

| Colorado | Narrow | |

| Connecticut | Click-Through and Notice and Reporting | Narrow |

| Delaware | No Sales Tax | |

| Florida | n.a. | |

| Georgia | Click-Through | n.a. |

| Hawaii | Narrow | |

| Idaho | Click-Through | Broad |

| Illinois | Narrow | |

| Indiana | Broad | |

| Iowa | Click-Through and Cookie | Broad |

| Kansas | Click-Through and Notice and Reporting | Broad |

| Kentucky | Notice and Reporting | Broad |

| Louisiana | Click-Through and Notice and Reporting | n.a. |

| Maine | Click-Through | Narrow |

| Maryland | Narrow | |

| Massachusetts | Broad | |

| Michigan | Click-Through | n.a. |

| Minnesota | Click-Through | Narrow |

| Mississippi | n.a. | |

| Missouri | Click-Through | n.a. |

| Montana | No Sales Tax | |

| Nebraska | Narrow | |

| Nevada | Click-Through and Notice and Reporting | Broad |

| New Hampshire | No Sales Tax | |

| New Jersey | Click-Through | Broad |

| New Mexico | Narrow | |

| New York | Click-Through | Narrow |

| North Carolina | Click-Through | n.a. |

| North Dakota | Broad | |

| Ohio | Broad | |

| Oklahoma | Notice and Reporting | Narrow |

| Oregon | No Sales Tax | |

| Pennsylvania | Click-Through and Notice and Reporting | Narrow |

| Rhode Island | Click-Through and Cookie | Broad |

| South Carolina | Click-Through and Cookie | Narrow |

| South Dakota | Notice and Reporting | Narrow |

| Tennessee | Click-Through and Cookie | n.a. |

| Texas | Narrow | |

| Utah | Broad | |

| Vermont | Click-Through and Notice and Reporting | Broad |

| Virginia | Broad | |

| Washington | Broad | |

| West Virginia | Broad | |

| Wisconsin | Narrow | |

| Wyoming | Narrow | |

| District of Columbia | Narrow | |

Legalization and Taxation of Marijuana

As public attitudes toward marijuana have changed, states are increasingly revisiting their statutes on the possession, sale, and taxation of marijuana. Many states now allow medical marijuana, others have decriminalized possession, and a small but growing number have legalized recreational marijuana. Thus far, every state which has legalized marijuana has done so in concert with the implementation of a new excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. regime.

A marijuana-specific tax regime is not theoretically essential, as it could, post-legalization, simply fall under the state sales tax like most other consumer goods. The notion that marijuana (like tobacco products, alcohol, and select other goods) should have its own tax regime has, however, been largely uncontroversial. These taxes also fund the states’ marijuana regulatory regimes, though in all cases they raise revenue considerably in excess of these costs and help fund general governmental expenditures.

Curiously, 2019 itself was a slow year for legalization, with only Illinois adopting such a regime over the past year, joining 10 other states as of the Illinois statute’s effective date of January 1, 2020. Michigan chose to implement an already-planned legalization in December 2019 rather than in the spring of 2020.[20] Only eight states, however, closed 2019 with active markets.

Illinois’ tax regime is needlessly complex, with a 7 percent excise tax on wholesale value combined with a 10 percent tax on cannabis flowers or products with less than 35 percent THC, a 20 percent tax on edibles and other cannabis-infused products, and a 25 percent tax on any product with a THC concentration of 35 percent or higher. State and local sales taxes also apply. Illinois is, to date, the only state to tax on the basis of potency.

Despite the slowdown in 2019, however, 2020 is already shaping up to be a significant year on marijuana policy. The governors of five northeastern states—Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island—are collaborating in developing a potential common framework on legalization and taxation of marijuana,[21] and Arizona, Florida, New Jersey, and Ohio could all see ballot measures on legalization this year. Other states are sure to consider legalization and taxation as well. Still, while some legislation can be expected, lawmakers across the country have demonstrated a marked preference for leaving the decision to voters at the ballot.

Excise taxes tended to be quite high when states first began legalizing marijuana. In 2016, the four states with recreational marijuana were Washington with a 37 percent excise tax, Colorado at 29 percent, and Alaska and Oregon at 25 percent. These rates may have been too high to drive out gray and black markets.[22] Since then, Alaska, Colorado, and Oregon have reduced marijuana tax burdens, and states which implemented marijuana excise taxes since then have tended to adopt lower rates. As more states contemplate marijuana legalization, they are likely to consider excise tax rates closer to those adopted in 2017 through 2019 than those set in 2016.

Taxation of Sports Betting

The Supreme Court’s 2018 decision in Murphy v. National Collegiate Athletic Association opened the way to the legalization and taxation of sports betting, and states are wasting no time joining the playing field.

Sports betting has changed since the 1992 law was enacted, particularly with the rise of daily fantasy sports. Not only can bettors lay odds on a team winning straight up or against the spread, but they can engage in fast-paced in-game betting on discrete events, such as how many three-pointers in basketball will be made or whether the current drive in football will end with an interception. These in-game bets enhance the importance of the integrity of in-game data, at least theoretically. That has been the crux of the argument professional sports leagues—particularly Major League Baseball (MLB) and the National Basketball Association (NBA)—have advanced for so-called “integrity fees,” in which as much as 1 percent of the “handle” (the total amount of bets taken) would be remitted to the league to offset the costs of maintaining the data on which bets are based, and in compensation for generating the product (the games themselves) which make betting possible.

Many policymakers have questioned the justifications for these integrity fees, and by the end of 2018, some proponents were calling them royalties, which comes closer to explaining the real basis of the claim. Actual royalties, though, would not require the state to act as collector; unfortunately for sports leagues, there is little legal precedent to support the notion that statistics and scores constitute intellectual property. In 2018, many states were contemplating integrity fees, but by the close of 2019, the leagues appear to be losing that battle.

States which have already legalized casino gambling are particularly likely to permit sports betting, but they should be conservative in their revenue estimates. Daily fantasy sports and other online options largely out of reach of state tax regimes will limit taxable betting activity, and collections are likely to be modest. If states adopt particularly high taxes, they are likely to discourage in-person betting in competition with online alternatives which are far harder to tax, or even competition across state lines.

Similar to issues raised by marijuana legalization, brick-and-mortar sports betting facilities will be competing with black and gray markets, and setting tax rates too high could keep bettors in untaxed markets. Initially, moreover, a state which legalizes sports betting may attract bettors across state lines, but this effect should dissipate as more states legalize wagering on sports.

In 2019, eight states approved sports betting and taxation, joining 12 other states and the District of Columbia which already had active sports betting markets. Colorado voters approved a measure legalizing sports betting in casinos and online and imposing a tax of 10 percent of adjusted gross revenues, while in Illinois, the legislature green-lit a 15 percent tax. Indiana set a rate of 9.5 percent, while Iowa now taxes sports betting at 6.75 percent, which is tied with Nevada—which was grandfathered in under prior law—for the lowest rate.

Michigan began allowing in-person and online sports betting in December, with an excise tax rate of 8.4 percent. New Hampshire, meanwhile, bucked trends in other states by authorizing a single company, DraftKings, to run its legalized sports betting system, and requiring them to remit 51 percent of gross revenue for online bets to the New Hampshire lottery fund, with a 50 percent tax on in-person bets at casinos.[23] Tennessee, the only state to exclusively authorize online betting, adopted a tax rate of 20 percent. Finally, two states took different routes, with Montana authorizing sports betting run exclusively by the state lottery and North Carolina approving sports betting only on tribal lands.

|

Source: State statutes; Tax Foundation research. |

|

| State | Tax Rate |

|---|---|

| Colorado | 10% |

| Illinois | 15% |

| Indiana | 9.5% |

| Iowa | 6.75% |

| Michigan | 8.4% |

| Montana | Lottery-run |

| New Hampshire | 51% online; 50% retail |

| North Carolina | Tribal lands |

| Tennessee | 20% |

States increasingly see sports betting as an easy way to obtain a modest revenue infusion, so the pace of adoption should not be expected to slacken any time soon. Most states seem to have settled on rates in the high single to low double digits; the major anomaly of 2019, New Hampshire, involves a monopoly grant to a single company.

Taxation of Vapor Products

The taxation of vapor products is expanding swiftly, with 11 states implementing new excise taxes on vaping in 2019, bringing the total number of states with such taxes to 20 plus the District of Columbia.

E-cigarettes are themselves relatively new, and states have struggled to determine if and how to tax them, though many have not hesitated to move forward even with uncertainties. When smokers shift to vapor products, this reduces cigarette tax revenue, but given that a stated purpose of most tobacco taxes is to improve health outcomes and reduce health-related expenditures, the harm reduction associated with these alternative products must be taken into account. Taxing vapor products identically with, or even more heavily than, traditional tobacco products creates a disincentive for smokers to shift to a less harmful product.

Vapor taxes come in two varieties: specific taxes based on the volume of e-cigarette liquid, in keeping with the standard approach to excise taxation, or ad valorem taxes on the wholesale price. Excise taxes are generally designed to price externalities (user fee) or disincentivize a transaction (sin tax), or both. Specific taxes make more sense in either case, as the nature of the purchase, not its cost, is the relevant factor; potential harm is not predicated on price. Imposing ad valorem taxes incentivizes the purchase of lower-cost and perhaps lower-quality products, and the resulting revenue is less predictable for states.

Nevertheless, many states choose to impose ad valorem taxes, using price as a proxy for different potencies. As a superior alternative, states can—and sometimes do—set two specific rates, one for closed tank systems that have higher nicotine levels per milliliter, and another for open tank systems with a lower nicotine concentration.[24]

In 2019, Connecticut and New Mexico implemented bifurcated excise taxes which taxes open systems on an ad valorem basis and closed systems on volume. Washington now taxes open and closed tank systems at different specific rates (9 and 27 cents, respectively), while Ohio and Wisconsin impose specific excise tax rates that apply equally to all systems. The remaining states—Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, New York, Nevada, and Vermont—all adopted ad valorem taxes on vapor products in 2019.

|

Sources: State statutes; Tax Foundation research. |

|

| State | Tax Rate(s) |

|---|---|

| Connecticut | $0.40 per ml. closed tanks

10% wholesale other vapor products |

| Illinois | 15% wholesale |

| Maine | 43% wholesale |

| Massachusetts | 75% wholesale |

| Nevada | 30% wholesale |

| New Mexico | $0.50 closed tanks

12.5% wholesale open tanks |

| New York | 20% retail |

| Ohio | $0.10 per ml. |

| Vermont | 92% wholesale |

| Washington | $0.09 per ml. open tanks

$0.27 per ml. closed tanks |

| Wisconsin | $0.05 per ml. |

In 2018, vapor taxation was mainly a matter of revenue, with states seeking to capture some of the lost revenue as some smokers transitioned to vapor products. This is not to deny that health was a consideration, but vapor products were largely seen as harm reduction products compared to traditional cigarettes. In 2019, deaths linked to (mostly counterfeit and THC-laced) vapor products, along with escalating opposition to flavored products deemed more attractive to children (recently restricted by the Trump administration), emerged as a more significant basis for taxation along with regulatory constraints, even though higher taxes might expand the appeal of black market products.

From this arises the major uncertainty for 2020. Vapor products will undeniably be at the forefront for many legislators this year, though there may be competing impulses—taxing for revenue versus taxing to restrict access, or instead limiting or banning vapor products altogether.

Gas TaxA gas tax is commonly used to describe the variety of taxes levied on gasoline at both the federal and state levels, to provide funds for highway repair and maintenance, as well as for other government infrastructure projects. These taxes are levied in a few ways, including per-gallon excise taxes, excise taxes imposed on wholesalers, and general sales taxes that apply to the purchase of gasoline. Increases

States continue to adjust their motor fuel tax rates, which had long eroded due to inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. . Today, a growing number of states automatically index their gas taxes to inflation or, less ideally, incorporate wholesale gasoline prices into the rate calculation. Four states—Alabama, Arkansas, Illinois, and Ohio—adopted new rate increases in 2019, and Tennessee implemented the second stage of a rate increase that began in 2018. The largest increase was in Illinois, where the excise doubled from 19 to 38 cents per gallon and will henceforth be indexed for inflation.[25]

Other Tax Issues

The estate tax continues to die a slow death, while changing energy markets may force difficult choices on some states.

Declining Estate TaxAn estate tax is imposed on the net value of an individual’s taxable estate, after any exclusions or credits, at the time of death. The tax is paid by the estate itself before assets are distributed to heirs. Burdens

Until 2005, taxpayers received a federal credit for state inheritance and estate taxes paid, essentially rendering them (up to a certain limit) a way for states to raise additional revenue at no additional cost to their taxpayers. Since the phaseout of that provision, states have been moving away from estate and inheritance taxes, a trend that continues unabated. Before the credit’s repeal, all 50 states had an estate or inheritance taxAn inheritance tax is levied upon the value of inherited assets received by a beneficiary after a decedent’s death. Not to be confused with estate taxes, which are paid by the decedent’s estate based on the size of the total estate before assets are distributed, inheritance taxes are paid by the recipient or heir based on the value of the bequest received. . Today only 17 do, following the repeal of estate taxes in Delaware and New Jersey in 2018. (New Jersey also imposes an inheritance tax. With estate tax repeal, Maryland is now the only state to impose both an inheritance and an estate tax.)[26]

As part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the federal exclusion amount was doubled to $11.58 million as of 2020 (an inflation-adjusted $10 million), which in turn prompted higher exemptions in a number of states which conform to federal provisions. There is a growing realization, moreover, that estate taxes can be counterproductive, driving high-net-worth retirees (who tend to be highly mobile) out of state, thus losing not only the potential estate tax revenue, but also years of income, sales, property, and other tax collections. Estate taxes are thus highly inefficient, since the revenue comes at a cost of reduced investment by (and tax liability for) high-net-worth individuals due to outmigration.

For now, some states with thresholds below the new federal level are raising their own exemptions. In a recent policy development, for instance, Connecticut now matches the old federal level as of 2020 and will continue to phase in the new, higher exemptions. The result of prior legislation, Minnesota’s estate tax exemptionA tax exemption excludes certain income, revenue, or even taxpayers from tax altogether. For example, nonprofits that fulfill certain requirements are granted tax-exempt status by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), preventing them from having to pay income tax. rose to $3 million in 2020, and Vermont’s rose from $2.75 million to $4.25 million.[27] Other states are likely to follow. Longer term, there is every reason to expect that more states will follow in the footsteps of Delaware, New Jersey, and those that have already abandoned these taxes.

Comprehensive Reform

Recent years have witnessed the return of comprehensive tax reform in its most robust form since at least states’ responses to the Tax Reform Act of 1986, if not earlier. Whereas lawmakers once preferred to tackle one tax at a time, increasingly reform has gained additional viability by becoming broader, not narrower, permitting necessary trade-offs and benefiting a wider range of taxpayers. States like Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, North Carolina, and Utah are indicative of this trend, and in 2019, Utah adopted a reform package affecting multiple taxes (touching individual income taxes, corporate income taxes, sales taxes, and excise taxes) for the second time in 12 years. States do continue to pursue discrete changes to a single tax, but policymakers have come to see benefits in addressing multiple taxes at once rather than conducting an overhaul of one tax at a time.

Revenue Challenges in Energy States

No state has adopted a new income tax since 1991, nor a new sales tax since 1969,[28] but that streak could be threatened in coming years, particularly as resource-intensive states struggle to cope with changing energy markets. In 2019, Wyoming’s joint revenue committee referred legislation creating a corporate income tax for consideration in the 2020 legislative session.[29] Steeply declining oil and gas revenues are generating talk of a possible sales or even individual income tax in Alaska.[30] Montana does not meet in legislative session in 2020 but will use the off year for a tax study which might consider the adoption of a state sales tax to permit reforms to other taxes.[31] More broadly, states which rely heavily on severance taxes or property taxes on those industries are increasingly experiencing revenue contractions and lowering their expectations for coming years.

Conclusion

The year 2019 was an eventful one in the realm of state taxation, but no slackening should be expected soon—not even in states’ responses to the major upheavals of 2018 (Wayfair and the TCJA, and to a lesser extent Murphy). State interest in taxing remote sales and legalizing and taxing both sports betting and marijuana should continue unabated. While most states now conform, at least in part, to the new federal tax law, many important considerations, from how to handle the international provisions to what to do with the revenue, will continue to occupy lawmakers’ attention in 2020. States are only now figuring out their marketplace facilitator laws, and revisions are likely.

Long-term trends, like the declining importance of corporate income taxes and starker economic implications of retaining an estate tax, will continue to figure into states’ tax considerations. In recent years, moreover, tax plans have increasingly been comprehensive, reforming multiple taxes at once rather than being limited to a single tax. Often previously considered too daunting, comprehensive reform is increasingly viewed as more practical, as it allows reforms to be balanced against each other.

The future of state taxation no doubt holds a few surprises, but a key to many future developments can be found in the experience of other states. Policymakers would do well to pay attention to the experiences of their peers—to learn from their mistakes as well as their successes.

[1] Daniel Defoe, The Political History of the Devil (London: T. Warner, 1726), 269.

[2] Jared Walczak and Erica York, “GILTI and Other Conformity Issues Still Loom for States in 2020,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 19, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/gilti-state-conformity-issues-loom-in-2020/; Jared Walczak, “Tax Reform Moves to the States: State Revenue Implications and Reform Opportunities Following Federal Tax Reform,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 31, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/state-conformity-federal-tax-reform/.

[3] In some cases, the implications cannot be wholly avoided by failing to conform to the IRC post-TCJA. For instance, Virginia expressly decouples from the provisions of the new federal law, but it requires filers’ choice to take the federal standard deduction to be replicated on their state tax forms. Because many more filers will benefit from taking the federal standard deduction, Virginia can expect additional revenue as these filers must now take Virginia’s standard deduction even though, all else being equal, they would benefit from being able to itemize at the state level.

[4] Jared Walczak and Erica York, “GILTI and Other Conformity Issues Still Loom for States in 2020.”

[5] Id.

[6] Scott Greenberg, “Pass-Through Businesses: Data and Policy,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 17, 2017, 7, https://taxfoundation.org/pass-through-businesses-data-and-policy/.

[7] Jared Walczak, “Tax Changes Taking Effect January 1, 2019,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 27, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/state-tax-changes-january-2019/.

[8] Katherine Loughead, “State Tax Changes as of January 1, 2020,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 20, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/2020-state-tax-changes-january-1/.

[9] Jared Walczak, “Tax Changes Taking Effect January 1, 2019.”

[10] Jared Walczak, “Missouri Governor Set to Sign Income Tax Cuts,” Tax Foundation, July 11, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/missouri-governor-set-sign-income-tax-cuts/.

[11] Jared Walczak, “Utah Passes Tax Reform Bill in Special Session,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 12, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/utah-sales-tax-reform/.

[12] Katherine Loughead, “State Tax Changes as of January 1, 2020.”

[13] Jared Walczak, “Tax Changes Taking Effect January 1, 2019.”

[14] Katherine Loughead, “State Tax Changes as of January 1, 2020.”

[15] Id.

[16] U.S. Census Bureau, “Quarterly Retail E-Commerce Sales, 3rd Quarter 2019,” CB19-170, Nov. 19, 2019, https://www.census.gov/retail/mrts/www/data/pdf/ec_current.pdf.

[17] South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc., 585 U.S. ___ (2018).

[18] Jared Walczak and Janelle Cammenga, “State Sales Taxes in the Post-Wayfair Era,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 12, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/state-remote-sales-tax-collection-wayfair/.

[19] Id.

[20] Lauren Gibbons, “Recreational marijuana rollout in Michigan could be national model for how not to do it, industry insider says,” mlive.com, Dec. 13, 2019, https://www.mlive.com/public-interest/2019/12/recreational-marijuana-rollout-in-michigan-could-be-national-model-for-how-not-to-do-it-industry-insider-says.html.

[21] State of New Jersey news release, “Governor Cuomo, Governor Lamont, Governor Murphy, and Governor Wolf, Co-Host Regional Cannabis Regulation and Vaping Summit,” Oct. 17, 2019, https://www.nj.gov/governor/news/news/562019/approved/20191017c.shtml.

[22] Joseph Bishop-Henchman and Morgan Scarboro, “Marijuana Legalization and Taxes: Lessons for Other States from Colorado and Washington,” Tax Foundation, May 12, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/marijuana-taxes-lessons-colorado-washington/.

[23] New Hampshire H.B. 480 (2019).

[24] Ulrik Boesen, “Vaping Taxes Should Be Carefully Designed,” Tax Foundation, Sept. 12, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/vaping-taxes-carefully-designed/.

[25] Jamie Munks and Dan Petrella, “Gov. J.B. Pritzker signs bills that ignite $45 billion construction program, massive gambling expansion and doubling of gas tax,” Chicago Tribune, June 28, 2019, https://www.chicagotribune.com/politics/ct-jb-pritzker-gambling-construction-bills-gas-tax-signed-20190628-inux5umelbewje5zzdrpphz3ze-story.html.

[26] Jared Walczak, “State Inheritance and Estate Taxes: Rates, Economic Implications, and the Return of Interstate Competition,” Tax Foundation, July 17, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/state-inheritance-estate-taxes-economic-implications/.

[27] Katherine Loughead, “State Tax Changes as of January 1, 2020.”

[28] Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations, Significant Features of Fiscal Federalism, Volume 1, September 1995, 32, https://library.unt.edu/gpo/acir/SFFF/sfff-1995-vol-1.pdf.

[29] Jared Walczak, “Throwback, Pricing Strategies, and a Wyoming Corporate Tax,” State Tax Notes, July 22, 2019, https://www.taxnotes.com/lr/resolve/tax-notes-state/throwback-pricing-strategies-and-a-wyoming-corporate-tax/29pyf.

[30] Andrew Kitchenman, “Budget Scenarios Include ‘Balanced Approach’ That Draws Interest,” Alaska Public Media and KTOO-Juneau, Dec. 18, 2019, https://www.alaskapublic.org/2019/12/18/budget-scenarios-include-balanced-approach-that-draws-interest/.

[31] Corin Cates-Carney, “Montana Lawmakers Plan Tax Policy Review,” Montana Public Radio, May 22, 2019, https://www.mtpr.org/post/montana-lawmakers-plan-tax-policy-review.

Share this article