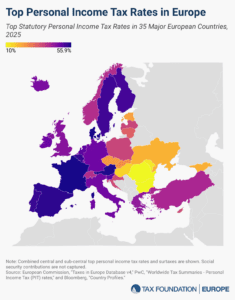

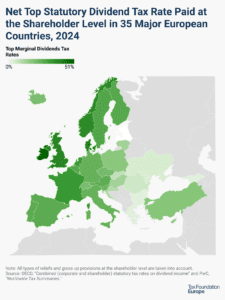

Top Personal Income Tax Rates in Europe, 2025

Denmark (55.9 percent), France (55.4 percent), and Austria (55 percent) levy the highest top personal income tax rates in Europe.

4 min readProviding journalists, taxpayers, and policymakers with the latest data on taxes and spending is a cornerstone of the Tax Foundation’s educational mission.

As a nonpartisan, educational organization, the Tax Foundation has earned a reputation for independence and credibility.

Our EU tax policy team regularly provides accessible, data-driven insights from sources such as the European Commission, the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), and others.

Denmark (55.9 percent), France (55.4 percent), and Austria (55 percent) levy the highest top personal income tax rates in Europe.

4 min read

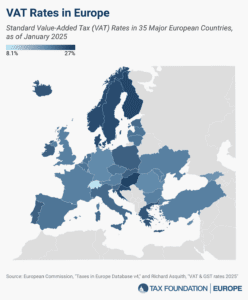

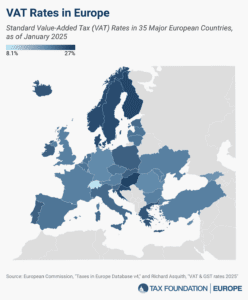

More than 175 countries worldwide—including all major European countries—levy a value-added tax (VAT) on goods and services. EU Member States’ VAT rates vary across countries, though they’re somewhat harmonized by the EU.

5 min read

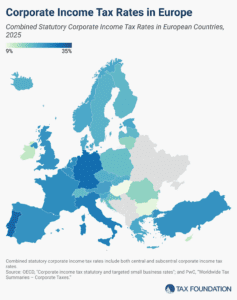

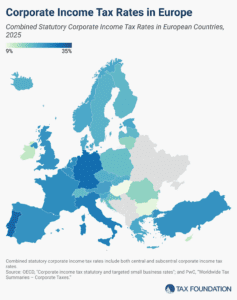

Some European countries have raised their statutory corporate rates over the past year, including Czechia, Estonia, Iceland, Lithuania, and Slovenia.

3 min read

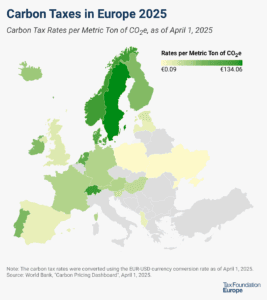

In recent years, several countries have taken measures to reduce carbon emissions, including instituting environmental regulations, emissions trading systems (ETSs), and carbon taxes.

4 min read

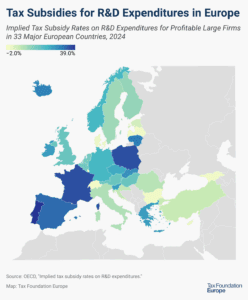

Many countries incentivize business investment in research and development (R&D), intending to foster innovation. A common approach is to provide direct government funding for R&D activity. However, a significant number of jurisdictions also offer R&D tax incentives.

4 min read

To make the taxation of labor more efficient, policymakers should understand their country’s tax wedge and how their tax burden funds government services.

5 min read

Carryover provisions help businesses “smooth” their risk and income, making the tax code more neutral across investments and over time.

5 min read

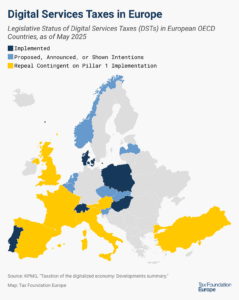

Currently, about half of all European OECD countries have either announced, proposed, or implemented a digital services tax. Because these taxes mainly impact US companies and are thus perceived as discriminatory, the US responded with retaliatory tariff threats.

5 min read

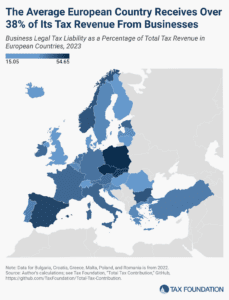

Without businesses as their taxpayers and tax collectors, governments would not have the resources to provide even the most basic services.

5 min read

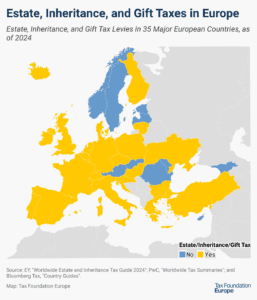

Twenty-four out of the 35 European countries covered in this map currently levy estate, inheritance, or gift taxes.

3 min read

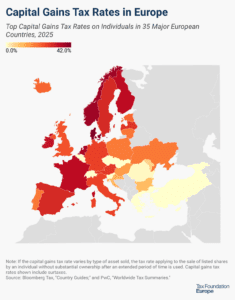

Many countries’ personal income tax systems tax various sources of individual income—including investment income such as dividends and capital gains.

4 min read

Capital gains taxes create a bias against saving, leading to a lower level of national income by encouraging present consumption over investment.

5 min read

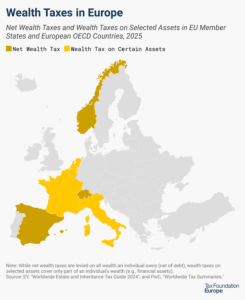

Wealth taxes not only collect little revenue and create legal uncertainty, but an OECD report argues that they can also disincentivize entrepreneurship, harming innovation and long-term growth.

5 min read

Denmark (55.9 percent), France (55.4 percent), and Austria (55 percent) levy the highest top personal income tax rates in Europe.

4 min read

More than 175 countries worldwide—including all major European countries—levy a value-added tax (VAT) on goods and services. EU Member States’ VAT rates vary across countries, though they’re somewhat harmonized by the EU.

5 min read

Some European countries have raised their statutory corporate rates over the past year, including Czechia, Estonia, Iceland, Lithuania, and Slovenia.

3 min read

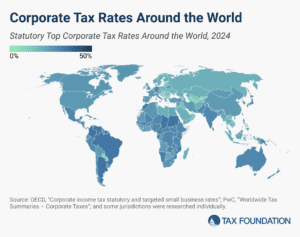

The worldwide average statutory corporate tax rate has consistently decreased since 1980 but has leveled off in recent years. In the US, the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act brought the country’s statutory corporate income tax rate from the fourth highest in the world closer to the middle of the distribution.

18 min read

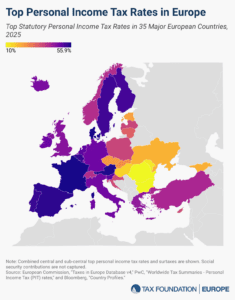

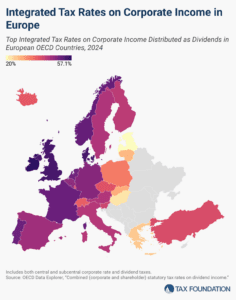

In most European OECD countries, corporate income is taxed twice, once at the entity level and once at the shareholder level.

4 min read

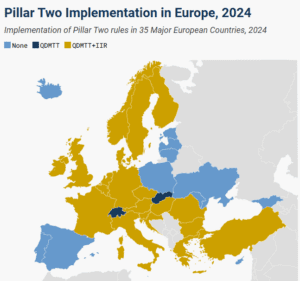

18 of the 27 EU Member States have implemented both the income inclusion rule and the qualified domestic minimum top-up tax in 2024.

4 min read

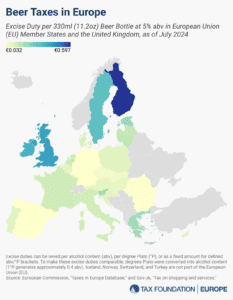

As Oktoberfest celebrations wrap up across the continent, now is a great time to examine beer taxes in the European Union. Hefty beer taxes add to the price of every drink consumed.

5 min read

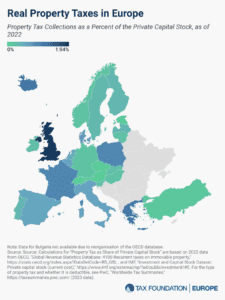

High property taxes levied not only on land but also on buildings and structures can discourage investment in infrastructure, which businesses would have to pay additional tax on.

3 min read

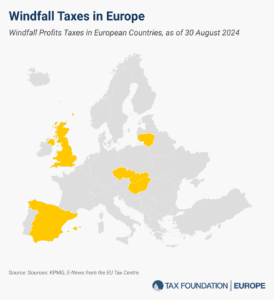

The flawed design of these windfall profits taxes has created problems in countries that implemented them.

4 min read

Explore the latest EU tobacco and cigarette tax rates, including EU excise duties on cigarettes. Compare cigarette taxes in Europe.

3 min read