Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- The Current Crisis in Context

- — New York’s Competitive Standing

- — New York’s Recent Reforms

- — New York’s Budget Gap

- — Prospects for Federal Relief

- — The State and Local Tax Deduction (SALT) Cap and New York’s Fiscal Capacity

- — New York’s Convenience Rule and the Future of Remote Work

- Evaluating New York’s Revenue Options

- — Mark-to-Market Taxation of Capital Gains Income

- — Stock Transfer Tax

- — Raising Income Tax Rates

- — Taxing Digital Advertising

- — Taxing Consumer Data

- — Modernizing the Sales Tax

- — Pied-à-Terre Tax

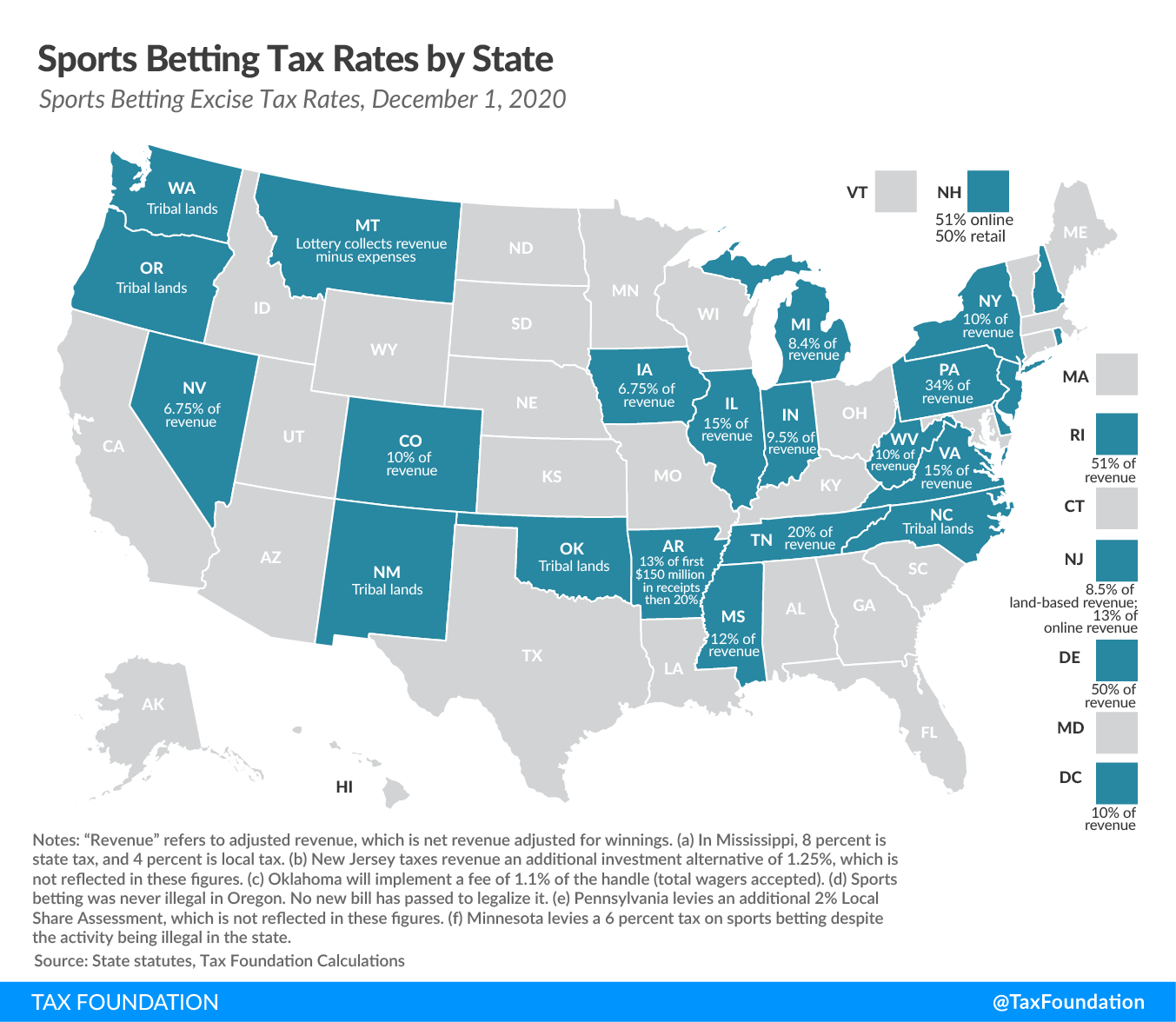

- — Legalizing and Taxing Gaming and Marijuana

- — Revisiting Costly Incentives

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

At first glance, New York faces projected budget shortfalls as arresting as the New York City skyline, and to meet the challenge, some have proposed taxes that would rival that skyline for staggering height. The challenge confronting policymakers is real, though perhaps not as dire as once feared. Its intensity depends on the pace of recovery, the availability of additional federal aid, and the policy choices state officials make in a state that has borne the brunt of the pandemic. State lawmakers will be called upon to navigate between two forbidding shoals, finding a way to meet the state’s revenue needs from a currently diminished tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. without implementing policies that make those economic losses permanent.

It is no easy task, and there are no pat answers. In this publication, we examine the scope of the losses New York confronts and the prospects for—and potential extent of—federal relief in helping alleviate the state’s fiscal crisis. Then, situated in the context of New York’s past efforts to improve its taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. competitiveness, and the importance of maintaining the Empire State’s attraction in an increasingly mobile economy, we review many of the proposals for raising additional revenue. Some hold promise, others present economic perils, and a few are legal quagmires.

Recent data from the New York Department of Taxation and Finance suggest four-year tax revenue losses of $20.9 billion in real terms, about a 6.7 percent inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. -adjusted decline across the period, and a challenge above what the figures would indicate for a state that was struggling to balance its budgets even before the COVID-19 pandemic. If federal aid were provided on par with what U.S. House Democrats proposed in May, a state share currently estimated at just under $26.9 billion would cover the gap and then some, while an additional $22.8 billion would benefit New York City and other struggling municipalities, making it easier for them to absorb not only their own revenue losses but also a reduction in state aid.

But these levels are by no means guaranteed, nor are tax revenues the only sources of revenue loss for New York. Further savings, in the form of both budget cuts and revenue increases, may be on the table, particularly if aid to either state or local governments falls well short of earlier proposals, as is quite plausible.

State officials, including Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D), have worried that raising the state’s already-high taxes could jeopardize long-term economic prospects, as New York loses out to more competitive tax environments. New York already imposes the nation’s second-highest tax burdens on individuals and fourth-highest burdens on businesses, leaving policymakers with little room to maneuver. The governor has expressed heightened concern in light of the capped state and local tax (SALT) deduction, though, as we discuss in this publication, the broader effects of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) meant that the adverse effects on New York’s fiscal capacity were overstated. Furthermore, President-elect Joe Biden’s tax proposal, even if coupled with the repeal of the SALT deduction cap, would not enhance the state’s fiscal capacity.

The SALT deduction notwithstanding, there are in fact legitimate reasons to be worried about tax-influenced outmigration, especially after the pandemic’s forced experiment with remote work ushers in a more flexible, and geographically mobile, way of living and working. For high-net-worth individuals in particular, it has never been easier to move—and to avoid higher taxes, some already have, and more will.

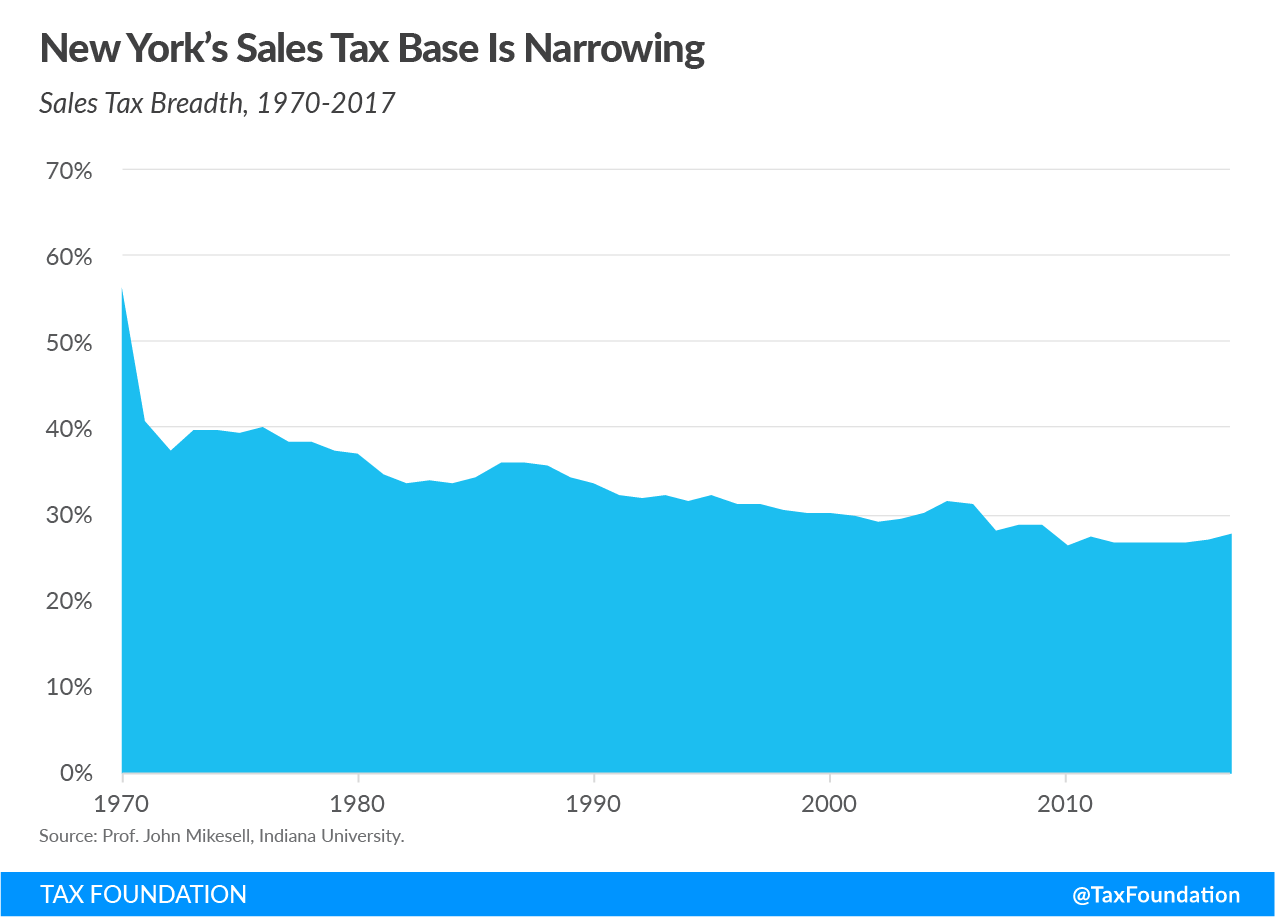

Some revenue options, like broadening the sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. base or briefly pausing currently scheduled income tax rate reductions, could bridge a revenue gap with limited harm to the state’s economic competitiveness. Similarly, legalization of gaming or marijuana, both of which have been advocated in some quarters, could create new revenue streams, though a legal marijuana market, in particular, would take some time to develop and would not yield significant new revenue immediately. Business incentives which fail to deliver on their promises should also come under greater scrutiny in light of budget shortfalls; a planned reduction in the state’s Excelsior Jobs Program Tax CreditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. s could be accelerated, and costly film tax credits which cost $420 million a year while failing to deliver for the state economically should be on the chopping block.

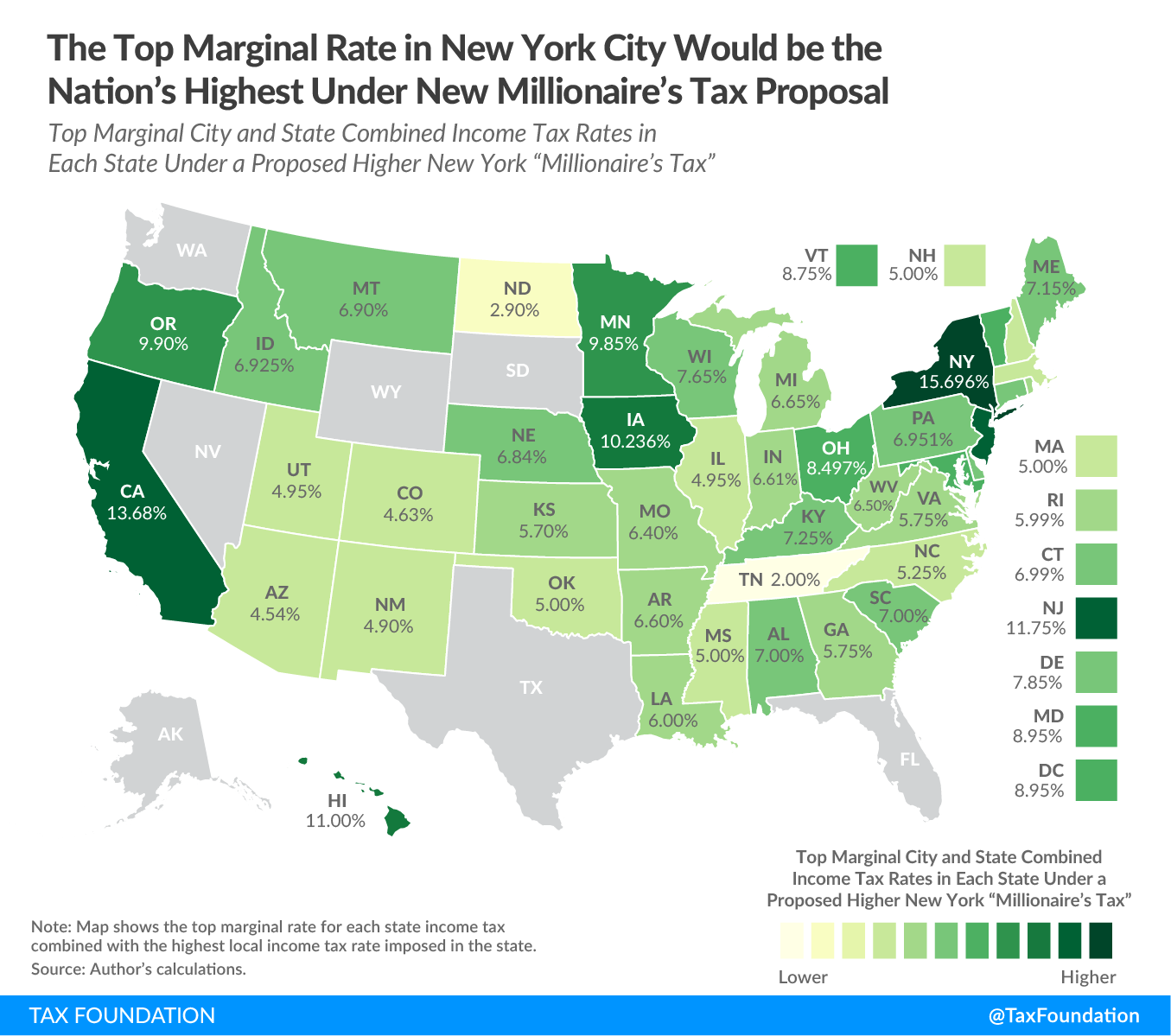

Other proposals under consideration, like a higher millionaire’s tax that could bring the top state and local combined rate in New York City to nearly 15.7 percent, could accelerate an outmigration that has already cost the state nearly a million residents and about $51 billion in annual adjusted gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total pre-tax earnings from wages, tips, investments, interest, and other forms of income and is also referred to as “gross pay.” For businesses, gross income is total revenue minus cost of goods sold and is also known as “gross profit” or “gross margin.” between 2010 and 2017 (most recent data). Evidence also suggests that authorizing New York City to impose a so-called pied-à-terre tax on second residences within the city, while superficially appealing as a way to export taxes to wealthy nonresidents, could backfire by driving out a subset of taxpayers who impose few costs on the city while contributing substantially to its tax base.

Then there are proposals that simply may not work at all. A mark-to-market proposal designed to accelerate the collection of capital gains taxA capital gains tax is levied on the profit made from selling an asset and is often in addition to corporate income taxes, frequently resulting in double taxation. These taxes create a bias against saving, leading to a lower level of national income by encouraging present consumption over investment. may be virtually unworkable, because it would require regular valuations of unpriced business interests and could require the liquidation of business assets to pay taxes on unrealized gains. A stock transfer tax could easily raise nothing at all, while depressing other sources of tax collections, by causing New York-based exchanges to relocate—a seismic shift that is nonetheless quite feasible in today’s highly interconnected economy, and which would be devastating for New York. The major exchanges have already indicated that they would relocate their servers to avoid a proposed New Jersey tax on processing the transactions; a relocation of the exchanges themselves, and the jobs that go with them, is a greater undertaking, but an increasingly viable one. And taxes on data and digital advertising, in addition to their many implementation challenges, run headlong into constitutional constraints.

Policymakers must manage a balancing act, meeting the state’s budgetary needs without getting in the way of economic recovery. Taxpayers, especially the high earners who are responsible for the lion’s share of state tax collections, are less geographically tethered than ever before; lawmakers must contend with higher mobility for businesses and individuals alike. But there’s still something special about New York, and always will be—something that will bring people back, if policymakers will allow it. The decisions made in Albany will influence what New York’s recovery looks like. This publication seeks to inform the important deliberations ahead by examining the magnitude of the revenue crisis and outlining the trade-offs policymakers must take into account as they craft their solutions.

Introduction

New York is a state of superlatives. It is the Empire State—even if no one is quite sure why. Certainly, however, no observer can deny New York’s claims to greatness. It is a state characterized by high energy, high hopes, high skylines, high culture, high frequency trading, and, yes, high taxes. It is, moreover, the kind of state that can get away with—justify, even—higher than average tax burdens. Whatever else they may be, taxes are part of the cost of living, and New York is undeniably a place that commands a premium.

New Yorkers have been willing to put up with higher-than-average tax burdens. They may grumble about them, but there is a degree to which they are an accepted cost of living in a desirable location with a large, active government sector. That does not, however, mean that the state faces no fiscal constraints. And as many in upstate New York have increasingly realized, a tax code that is manageable for wealthy New York City residents and businesses can prove incredibly burdensome elsewhere.

Some tax proposals, of course, might be unmanageable from almost any point of view. One advocacy effort suggests raising an additional $35 billion a year from the wealthiest New Yorkers, including $5.5 billion a year from a tax that targets about 120 people: an average of $46 million per taxpayer a year on a very small set of highly mobile individuals whose current presence in the state contributes immensely to existing revenues.[1] It is not so much a question of whether New York’s billionaires have the ability to pay—it is that many of them would have the ability not to, and would deprive the state of other much-needed revenue with their departure.

As a high-tax state, New York’s fiscal capacity is more constrained than some of its peers; remaining revenue options are more disruptive than the ones available to states which had exhausted or maxed out fewer revenue streams entering the COVID-19 pandemic. Taxes targeting the financial sector, which is at the heart of the state’s economy, could prove particularly damaging—catastrophic, even, if some of the more aggressive proposals led to an exodus of traders and exchanges. The financial sector is to New York what the technology sector is to California or agriculture to Nebraska. At the same time, however, the state’s budget gap is very real, and—absent generous federal assistance, which many policymakers continue to count on—exceeds the state’s realistic capacity to close through cuts alone.

This publication examines New York’s budget outlook and the tax competition the state faces. It explores New York’s revenue options—none of them good, but some better than others—as policymakers search for answers to the state’s budget crisis. Some proposals may have merit, if approached carefully:

- Modernizing the sales tax base could stabilize collections and generate additional revenue, particularly from higher-net-worth New Yorkers who are more likely to consume currently untaxed personal services;

- A temporary pause in scheduled income tax rate reductions can help offset immediate revenue losses while still assuring taxpayers of a downward, not upward, rate trajectory;

- The legalization and taxation of new markets in gaming and marijuana can be a welcome, if modest, source of additional tax revenue; and

- A reappraisal of the state’s corporate tax incentives can yield savings by reducing or eliminating underperforming credits.

Other proposals would prove considerably more harmful:

- Mark-to-market taxation would be virtually impossible to implement at the state level, and, if enacted, would break up many businesses whose owners have insufficient liquidity to pay taxes on the unrealized appreciation of their business interests;

- A stock transfer tax in such an interconnected, digitally-focused era could easily displace the major stock exchanges, and much of the state’s vital financial services sector with them;

- A higher “millionaire’s tax,” after failing to allow the current one to expire as planned, would undermine the state’s tax competitiveness and accelerate outmigration in an increasingly mobile economy;

- Taxation of digital advertising or consumer data is fraught with legal and practical pitfalls, and much of the burden would be borne by in-state businesses; and

- Authorization of a city pied-à-terre, which has been proposed as both a revenue-raiser and a disincentive for nonresidents to maintain a place in New York City, would see these goals in tension, as fewer high-net-worth individuals spend time in—and pay taxes—to the city and state.

This publication also argues that lawmakers should preserve the progress the state has made in recent years, not using the current crisis as an impetus for dramatic long-term tax experiments. Public officials from Gov. Andrew Cuomo on down have identified the economic perils of overreach, and that has never been truer than it is now.

New York is still a special place, and rumors of New York City’s demise are greatly exaggerated. Great cities are resilient; they bend, but do not break. The cavernous feel of the city’s great thoroughfares is temporary: people will return.

But not all of them.

Even before a global pandemic which ravaged New York and prompted an urban exodus, New York was losing more people (and income) to migration than it gained each year. Technology that brings us closer together was already eroding the need for physical proximity. Now, the telework experience is upending our conception of the workplace, or at least rapidly accelerating an existing trend. Most office workers will return, in time, but not all. Most businesses will retain their prior office locations, but not all. And in that “not all” there is a credible threat to New York’s finances. We have never had this much mobility before, and the advantages of being at the center of it all have never been weaker. Those eulogizing America’s great cities have arrived far too soon, but those unwilling to acknowledge symptoms and summon a doctor are far too sanguine.

The Current Crisis in Context

New York’s Competitive Standing

New York’s motto, “Excelsior,” means “higher,” but is commonly expressed as “ever upward.” In the Longfellow poem of that name, an intrepid young explorer braves a forbidding climate to complete his quest, but does not make it: he is found, having succumbed to unfavorable conditions, “still grasping in his hand of ice that banner with the strange device, Excelsior!”[2] The fate of New York businesses is not, perhaps, so dramatic, but the tension is there: New York is a state of ingenuity and innovation, but with a business climate that can be cold to the risk-takers that have so long defined the state.

New York ranks 48th in the 2021 edition of the Tax Foundation’s State Business Tax Climate Index, which measures tax structure, not rates or collections. On structure, the state does reasonably well on corporate taxes after the reforms of the past decade, but poorly on all other categories. At the same time, New York ranks 27th in CNBC’s most recent Top States for Business ranking, buoyed by high scores on access to capital (2nd), technology and innovation (4th), education (7th), and quality of life (13th) but dragged down by a high cost of doing business (42nd), a high cost of living (48th), and a lack of business friendliness (49th).[3] This encapsulates the tension of New York for businesses and individuals alike: the state has so much to offer, but sometimes the price of entry can be prohibitive.

| Component | Rank |

|---|---|

| Overall Rank | 48 |

| Corporate Taxes | 15 |

| Individual Taxes | 48 |

| Sales and Excise Taxes | 43 |

| Property and Wealth Taxes | 45 |

| Unemployment Insurance Taxes | 38 |

| Source: Tax Foundation. | |

Measured in nonbusiness taxes as a percentage of personal income, New York has the nation’s second-highest tax burden on individuals (an 8.1 percent effective rate), trailing only Hawaii (8.4 percent). The national average is 5.7 percent, making personal tax burdens more than 40 percent higher in New York than they are nationally. Propelled by top city and state combined income tax rates as high as 12.696 percent, along with above-average property and other tax burdens, these individual burdens are much higher than in other high-tax states in the region and are uncompetitive with most of New York’s peers nationwide.

| Nonbusiness State and Local Tax Burdens as a Percentage of State Personal Income, 2019 | |

|---|---|

| State | Personal Taxes as a % of Personal Income |

| New York | 8.1% |

| U.S. Average | 5.7% |

| Neighboring States | |

| Connecticut | 7.5% |

| Massachusetts | 6.5% |

| New Jersey | 6.6% |

| Pennsylvania | 5.8% |

| Rhode Island | 6.9% |

| Vermont | 5.8% |

| Select National Competitors | |

| California | 6.7% |

| Florida | 3.5% |

| Illinois | 6.2% |

| North Carolina | 5.6% |

| Texas | 3.7% |

| United States | 5.7% |

| Virginia | 5.4% |

| Washington | 4.9% |

| Sources: Council on State Taxation; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis; Tax Foundation calculations. | |

Businesses fare no better. They face the fourth-highest business taxes per employee in the country at $10,400 per employee, according to the Council on State Taxation, the cumulative effect of a panoply of state and local taxes on corporate income (imposed, unusually, by New York City in addition to the more traditional state-level tax), property, commercial rent, property transfers, business-to-business sales, and more. The only states with higher business taxes per employee—North Dakota, Wyoming, and Alaska, in that order—generate much of their tax revenue from capital-intensive oil and natural gas operations. Of states with broader economies, New York is without peer, in a bad way. Nationally, business taxes run about $6,500 per employee, putting New York’s taxes at a 60 percent premium.

| Business Tax Burdens Per Employee, 2019 | |

|---|---|

| State | Business Taxes Per Employee |

| New York | $10,400 |

| U.S. Average | $6,500 |

| Neighboring States | |

| Connecticut | $6,300 |

| Massachusetts | $5,900 |

| New Jersey | $8,800 |

| Pennsylvania | $6,200 |

| Rhode Island | $5,900 |

| Vermont | $8,400 |

| Select National Competitors | |

| California | $7,700 |

| Florida | $5,700 |

| Illinois | $6,800 |

| North Carolina | $4,300 |

| Texas | $7,700 |

| Virginia | $5,900 |

| Washington | $8,000 |

| Source: Council on State Taxation. | |

Some of the differences, for both individuals and businesses, can be explained by differences in these states’ respective economies, but such analysis only goes so far. New York’s concentration of high earners generates more revenue than the same rate structure would in a less affluent state, but this capacity does not go very far in explaining why New York requires such levels. A strong corporate presence in New York City provides the state with a large corporate tax base that other states may lack, but here too, this better explains the how than the why—and that “how” is dependent on New York’s ability to retain its businesses and high earners. Here, there is cause for concern.

Between 2010 and 2017 (most recent data), New York lost a net 963,182 residents to outmigration and, in aggregate, about $51 billion in annual adjusted gross income in current dollars, reflecting a state gross income loss of 5.4 percent.[4] About one-fifth of those leaving the state decamped to Florida, where they are shielded from both harsh winters and an individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. .[5]

Separately, the New York City Comptroller reports that the City’s population declined for the third consecutive year in 2019, losing 1.6 percent of its population over a three-year stretch in which the national population increased by 1.6 percent.[6] The COVID-19 pandemic, meanwhile, has likely both accelerated existing long-term outmigration trends and created some share of residents whose temporary relocations will become permanent, especially as remote work becomes more feasible.

In January, New York’s unemployment rate was 3.8 percent, only modestly higher than the national average of 3.6 percent. In September, the state’s rate stood at 9.7 percent, substantially higher than the national rate of 7.9 percent. (By October, the national rate had declined further, to 6.9 percent, but new state-level figures have not been released as of the date of this publication’s release.)[7] New York is strong, but New York is not invincible. The trends were already cutting against the state, and the pandemic and its aftermath will make them worse.

Taxes are only one of many considerations for businesses and individuals when they decide where to locate (or relocate). New York’s taxes are quite high, however, and contribute to the high cost of living and high cost of doing business. The financial sector, in particular, is essential to New York, generating almost 30 percent of gross state product, and higher taxes—particularly ones targeted at financial activity—could shift many of those jobs out of state, and tax dollars with them. As we enter into an era of greater mobility and flexibility, policymakers cannot afford to ignore the risks of an uncompetitive tax code, particularly one that so heavily targets a single industry.

New York’s Recent Reforms

Gov. Andrew Cuomo has left his mark on the tax code, convening two state tax relief commissions and implementing several of their recommendations earlier in his administration.[8] New York remains a high-tax state, but these reforms have improved the state’s competitiveness at a time when peer states like Massachusetts were also shedding their reputations for exorbitant taxation, and as taxpayer mobility increased.

Gov. Cuomo has overseen the reduction of the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate from 7.1 to 6.5 percent, its lowest rate since 1968. The corporate tax code was also improved through the elimination of the corporate alternative minimum tax, one of four tax bases under which the tax was then calculated, while beginning a phaseout of another base, measured by capital stock. That tax base is scheduled for repeal in 2021, the culmination of a six-year phasedown. The state also dramatically improved its treatment of corporations’ net operating losses, bringing its code in line with those of other states.[9]

The state improved 15 places on the corporate tax component of the Tax Foundation’s State Business Tax Climate Index, which measures tax structure, during the first four years of corporate tax reform,[10] though some of those gains have been lost in relative terms as other states have made more recent reforms.

Many individuals, meanwhile, have benefited from individual income tax rate cuts for the middle brackets, which will ultimately reduce the marginal rate on income below $80,650 ($161,550 for married filers) to 5.5 percent.[11] The state also adopted inflation indexingInflation indexing refers to automatic cost-of-living adjustments built into tax provisions to keep pace with inflation. Absent these adjustments, income taxes are subject to “bracket creep” and stealth increases on taxpayers, while excise taxes are vulnerable to erosion as taxes expressed in marginal dollars, rather than rates, slowly lose value. in 2011, ensuring that taxpayers do not see their effective rates increase due to bracket creepBracket creep occurs when inflation pushes taxpayers into higher income tax brackets or reduces the value of credits, deductions, and exemptions. Bracket creep results in an increase in income taxes without an increase in real income. Many tax provisions—both at the federal and state level—are adjusted for inflation. . A property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services. limitation regime, meanwhile, has kept the growth of local tax revenues in check,[12] and the state raised its formerly low estate taxAn estate tax is imposed on the net value of an individual’s taxable estate, after any exclusions or credits, at the time of death. The tax is paid by the estate itself before assets are distributed to heirs. thresholds.[13] At the same time, however, lawmakers chose to make the 8.82 percent top marginal rate permanent; it was originally scheduled to expire after 2017.[14]

The state’s higher top marginal rate notwithstanding—and it is a major caveat in an era of increased mobility—New York has, under Gov. Cuomo, recognized the role of tax competition and the risks associated with taxes that drive out the state’s top earners, who are also, of course, the drivers of state revenue. In 2016, tax filers earning less than $50,000 a year were responsible for less than 3 percent of income tax receipts, while filers earning more than $200,000 generated 63 percent of all income tax collections.[15]

| Individual Income Tax Liability by Income Class, Tax Year 2016 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Income Class | % of Filers | % of Liability |

| $0 – $49,999 | 64.1% | 2.8% |

| $50,000 – $99,999 | 19.7% | 14.8% |

| $100,000 – $199,999 | 11.1% | 20.0% |

| $200,000 + | 5.2% | 62.8% |

| Source: New York State Comptroller, “Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for Fiscal Year Ended March 31, 2019.” | ||

Although more recent data are not yet available, the gap will only have widened since then, as the “millionaire’s tax” rate has remained in place while other rates have been reduced. Many other state taxes are also disproportionately—or in the case of the estate tax, entirely—remitted by the highest-income New Yorkers. The temptation to generate additional revenues from the state’s wealthiest residents, particularly given the current downturn, must be tempered by a sober acknowledgment of how much state coffers stand to lose if too many of those wealthy taxpayers left.

New York Budget Gap

New York’s tax collections, though down from last year, do not look especially dire at first glance. The vacant office buildings of Manhattan tell a different story, one that is keeping state officials up at night. As of September 18th, only 10 percent of Manhattan office workers had returned, compared to 25 percent of office workers nationwide and even higher proportions in other large metropolitan areas, like Dallas (40 percent) and Los Angeles (32 percent), according to the commercial real estate services firm CBRE.[16] The Partnership for New York City published similar numbers in its late October survey, and reported that responding businesses expect only 48 percent of their employees to return by July 2021.[17] The result is devastating for businesses serving downtown employees (to say nothing of tourists), as well as to city revenues. They are also worrying to state officials who wonder, with reason, whether some of these workers—and their tax dollars—are gone for good.

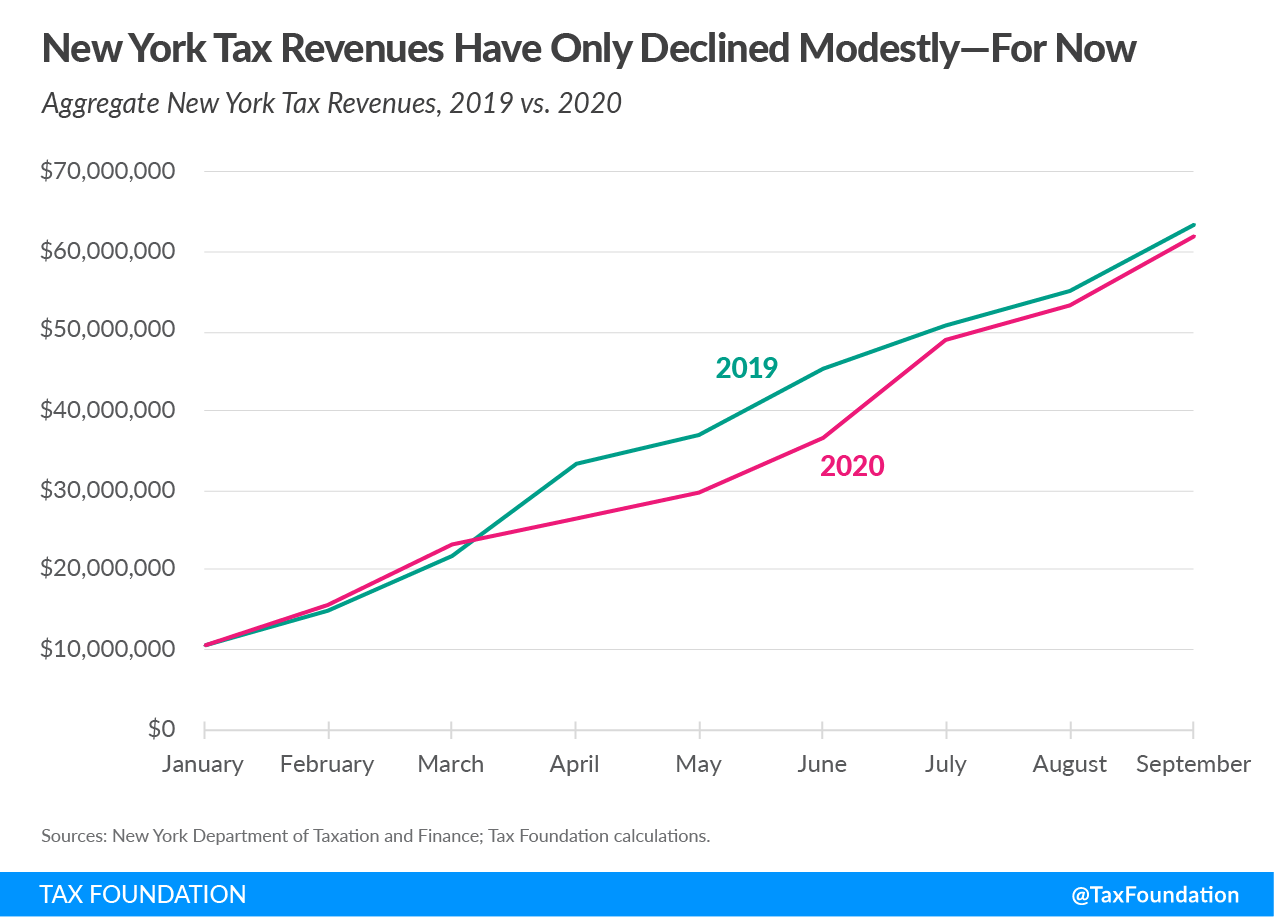

Between January and September of 2020, New York collected 2.5 percent less in taxes and fees than it did in the same nine months in 2019.[18] Tax revenues plummeted in April, when they fell nearly 69 percent, the combination of a decline in taxable activity (e.g., sales, tourism, withholdingWithholding is the income an employer takes out of an employee’s paycheck and remits to the federal, state, and/or local government. It is calculated based on the amount of income earned, the taxpayer’s filing status, the number of allowances claimed, and any additional amount of the employee requests. , nonresident income, and business profits) and the decision to delay the income tax filing deadline to July. A 137 percent spike in July collections made up for the latter, as taxes owed on 2019 income belatedly flowed to the state. By September, with delayed collections in the rearview mirror, monthly receipts were 4.4 percent higher than they were in the prior year.[19]

These revenue trends are not enough, on their own, to predict the crisis that state officials envision. To be sure, revenue collections will get worse before they get better: in New York as in the rest of the country, the full damage to income tax collections will not be realized until next April, the filing deadline for 2020 tax returns. And unlike in much of the country, where sales and excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. receipts have recovered to pre-recessionA recession is a significant and sustained decline in the economy. Typically, a recession lasts longer than six months, but recovery from a recession can take a few years. levels, New York’s heavy reliance on still-absent tourists, office workers, and other nonresidents has made a serious dent. Still, income tax withholding is fairly stable, which provides reason for optimism.

Yet, where many other states anticipate manageable losses, New York predicts crisis: in August 2020, the Division of the Budget anticipated total losses of $62.09 billion between Fiscal Years 2021 and 2024.[20] After accounting for enhanced federal matching assistance for Medicaid, the allocation of some spending to moneys received from the federal Coronavirus Relief Fund, and other savings and offsets, most notably a dramatic curtailment in local aid payments, the budget division expects the four-year gap to be a still daunting $27.4 billion.[21] At the same time, moreover, the reductions in local aid will intensify the fiscal crisis for municipalities.

New York, which had to close a $6.1 billion budget gap for FY 2021 before anyone had even heard of the novel coronavirus,[22] has been banking on revenue growth to help patch over its structural challenges and ever-growing budget. Before Gov. Cuomo offered a budget plan rolling back much of the planned growth of government this fiscal year, the FY 2021 budget was poised to be 7 percent larger than the prior year’s, with 9.4 percent growth in the general fund. This was entirely unsustainable even before the pandemic, and still worse, its baseline was an anomalously good year for revenue collections.

Tax receipts grew 9.7 percent in FY 2020, a dramatic leap from prior years. The individual income tax, for instance, generated $53.7 billion in FY 2020, compared to $48.1 billion the previous year. Adjusting for inflation, collections consistently hovered around $50 billion a year previously with no significant growth, before soaring to $53.7 billion in FY 2020, an increase that was likely the result of income-shifting in response to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) and not reflective of actual economic growth. Because New York’s fiscal years end in March, the most important revenue month for FY 2020 was April 2019, when final taxes on 2018 income were collected—a lengthy lookback which means that FY 2020 collections were substantially influenced by taxpayers who deferred earnings from tax years 2017 to 2018 to take advantage of the TCJA’s lower rates. This increase, therefore, is not real or sustainable; the FY 2019 figures were too low, and the FY 2020 figures too high, relative to the state of the actual economy.

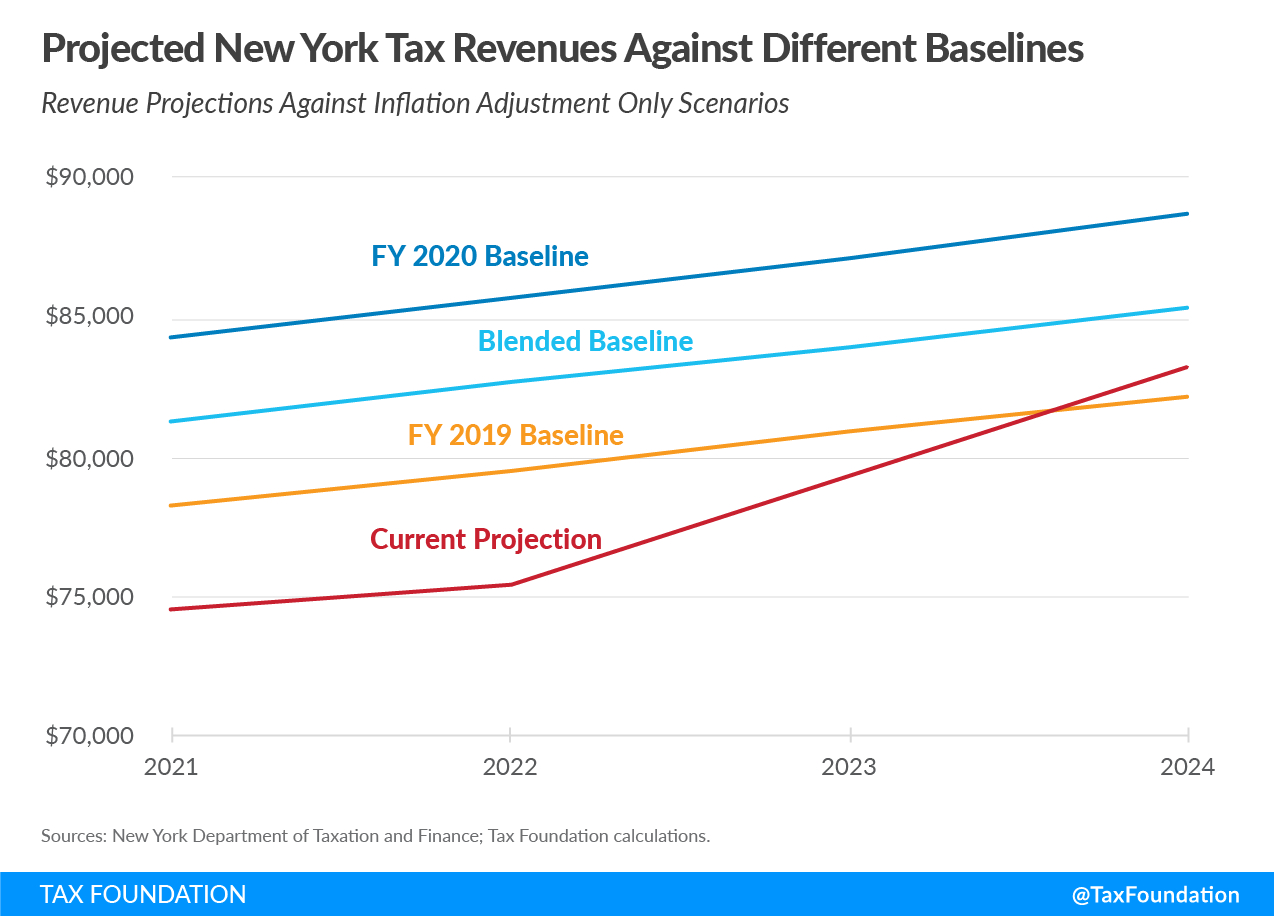

The dramatic projected decline in tax revenues looks, in part, like a reversion to the mean. In nominal terms, total tax revenues were $75.6 billion in FY 2019 and are projected to be $74.5 billion and $75.3 billion in FYs 2021 and 2022 respectively, a decline that looks less steep if the $82.9 billion figure from FY 2020 is not regarded as the new normal, which was already highly unrealistic. A blended baseline may be the most responsible approach, and suggests a four-year tax revenue loss of $20.9 billion compared to a scenario at which revenues had continued to grow at the rate of inflation, representing about a 6.7 percent inflation-adjusted decline across the period.[23]

Figure 2 shows projected revenues against each of these baselines, showing how projected revenues compare to three scenarios. Under the first, FY 2019 collections continue, rising only at the rate of inflation. Because of income shifting into FY 2020, this likely represents too low a baseline. The third, the FY 2020 baseline, benefits from that income shifting, and is therefore likely too high. The blended baseline averages the two years and inflation adjusts from that starting point.

Contributing to revenue estimators’ fears is the dreadful uncertainty of how, and where, people will work when the pandemic subsides. The novelist John Updike defined a true New Yorker as someone who secretly believes that people living anywhere else have to be, in some sense, kidding[24]—but right now, a fair percentage of New Yorkers themselves are living somewhere else, and they may not be kidding.

Many will return; offices will not be vacant forever. But a virus has upended the ways we live and work, and some of these changes will endure, with the pandemic accelerating nascent trends, like greater acceptance of telework and flexible working arrangements. “People are mobile. They will go to a better tax environment. That is not a hypothesis. That is a fact.”[25] These were Gov. Cuomo’s words in 2019, long before the country’s forced experiment in large-scale remote work. They look especially prescient, and worrisome, now.

A growing number of jobs can be performed from anywhere, and even for those that do remain office-bound, the benefits of being located in one of the country’s most expensive metropolitan areas may not be as strong as they once were. New York needs to prepare for this possibility and must take care not to rush headlong into tax plans that might accelerate these trends.

Prospects for Federal Relief

One likely bulwark against both spending reductions and tax increases is a new round of federal assistance. Anticipating the size, scope, and timing of any future federal aid to states is an uncertain proposition at best, particularly with the continuation of divided government with the election of Joe Biden as President but, pending the outcome of runoff elections, the retention of a Republican Senate disinclined to approve an additional relief package on the scale of the one favored by congressional Democrats. Some additional federal aid, however, appears likely, and may prove extremely helpful as the state weathers the current crisis. It is important to recognize, however, that any federal relief is definitionally temporary, and cannot be relied upon to address broader structural issues. New York’s expenditure trajectory vastly exceeded its anticipated growth in tax collections long before the COVID-19 pandemic, and, unless adjustments are made, will continue to do so long after any federal aid has run out.

Arguably one reason for the generosity of the Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions (HEROES) Act introduced by House Democrats in the spring of 2020, which would have extended state and local aid substantially in excess of the multiyear losses of these governments, is that creating a formula that could make a serious dent in the budget holes faced by a state like New York, which was hit particularly hard and faced pre-pandemic fiscal challenges, meant appropriating a total amount that looks vastly inflated compared to the needs of most other states.

The HEROES Act would have provided $540 billion in flexible aid to state governments and another $375 billion to local governments, in addition to about $81 billion in further enhanced Medicaid funding that would free up an equivalent amount in states’ budgets. This yields a total of at least $996 billion in flexible aid, plus $100 billion more for expenses arising from the COVID-19 pandemic.[26] About 54 percent of the flexible state aid calculation was based on population, while 37 percent is pegged to the state’s share of overall unemployment, and the remainder is tied to coronavirus cases, both (in the original bill) as of the spring of 2021.

When the bill was introduced in May, New York’s shares of both COVID-19 cases and total unemployment were much larger, and had the snapshot date for the formula been at that time, the Empire State would have been in line for $42.5 billion in aid. But the snapshot date was always for early 2021, and as time has passed and the virus’s damage is more keenly felt elsewhere (even if New York still bears disproportionate costs), the proportions—and pro rata shares—have changed. Using the latest data, New York’s share would be just under $26.9 billion. Another $22.8 billion would be available to New York municipalities, much of it flowing to New York City, and this calculation is not dependent upon economic or health data.

State and local aid under the HEROES Act was extremely generous. Not only was the bill introduced before officials had the advantage of second- and third-quarter economic and revenue data, but it was also drafted as a starting point in negotiations which quickly faltered. With aggregate state FY 2020 revenues only slightly down, little evidence of most states’ worst fears being realized,[27] and a significant decline in unemployment (to 6.9 percent in October,[28] compared with earlier projections that year-end unemployment would be around 10 percent), it is reasonable to expect that state relief would be smaller than what was embodied in the HEROES Act—even before divided government is taken into account. It is possible, however, that any future relief package may be more narrowly targeted, focusing more on economic indicators (like unemployment levels), which would favor New York in relative terms.

Even with generous federal assistance, however, New York may still be required to make its own further adjustments in the short term, and has no choice but to do so in the long term. The default governmental growth trajectory is unsustainable at present. Cuts not only in the rate of growth, but actual reductions in outlays, are necessary under the circumstances. Additional revenues, however, are also sure to be on the table, and are already the subject of strenuous debate. Be they income tax increases, a stock transfer tax, mark-to-market treatment of capital gains, digital services taxes, sales tax base broadeningBase broadening is the expansion of the amount of economic activity subject to tax, usually by eliminating exemptions, exclusions, deductions, credits, and other preferences. Narrow tax bases are non-neutral, favoring one product or industry over another, and can undermine revenue stability. , marijuana and gaming legalization and taxation, or any of a host of other proposals, policymakers will have much to consider.

This publication explores those options, examining revenue projections, economic considerations, and, where applicable, legal constraints. It highlights several potentially viable options for additional revenue, while sounding notes of caution about others which would put the state at a greater competitive disadvantage. Before doing so, however, it makes a detour to consider the effect of the state and local tax (SALT) deduction on New York’s fiscal capacity and risks surrounding New York’s so-called “convenience of the employer” income tax sourcing rule.

The State and Local Tax DeductionA tax deduction is a provision that reduces taxable income. A standard deduction is a single deduction at a fixed amount. Itemized deductions are popular among higher-income taxpayers who often have significant deductible expenses, such as state and local taxes paid, mortgage interest, and charitable contributions. (SALT) Cap and New York’s Fiscal Capacity

Gov. Cuomo and several other Northeastern governors have identified the $10,000 cap on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction, a feature of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017, as an impediment to their ability to raise revenue. In the process, the governor has articulated a particularly aggressive theory of tax flight, positing that this limitation on the tax code’s prior subsidy for high earners in high-tax states makes New York’s high taxes less attractive, exposing the state to more competition from lower-tax peers and thereby risking significant tax migration.

At a theoretical level, the governor is correct. “Tax the rich, tax the rich, tax the rich and now what do you? The rich leave,”[29] he declared, and this is correct—at some level. Without the cap, New York is, in his estimation, at a “long-term competitive disadvantage.”[30]

The federal tax code’s constraints on state fiscal capacity can be understood in both absolute and relative terms. An absolute constraint is imposed when federal taxes reduce income or investment in a way that reduces the state’s taxable base, or when they are high enough that taxpayers’ willingness to accept state levies is reduced. In an extreme case, the top federal income tax rate reached 92 percent in 1952, even though very few Americans had any income exposed to that rate.[31] Were this still in force today, New York’s current top marginal rate of 8.82 percent would yield a combined marginal rate in excess of 100 percent for some taxpayers in the absence of a deduction. But even in considerably less extreme cases, an increase in federal tax liability may diminish taxpayers’ appetite for state taxes.

A relative constraint, by contrast, is one that does not reduce a state resident’s ability to pay, but instead accentuates the competitive differences across different state tax regimes. The TCJA imposed a relative, not absolute, constraint on New York’s revenue options, because on net it represented a reduction in New Yorkers’ federal tax burdens—increasing ability to pay—but the tax savings were less pronounced in New York than they were in states with lower tax burdens.

Most taxpayers experienced tax savings in every state, including in New York, where federal income taxes paid by residents decreased by almost $3.4 billion in 2018, the first year the TCJA was in effect.[32] But while New Yorkers experienced tax savings, the benefit they could gain from relocating to a lower-tax jurisdiction also increased.[33] The SALT cap subsidy served to smooth out some of the differences in state tax liability for high earners; with the cap, the distinctions between state tax systems matter more.

Importantly, the reduction in federal taxes under the TCJA lowers the value of the SALT deduction. Because the TCJA lowered individual rates, the benefit of the SALT deduction would have been less even if uncapped. The legislation also repealed a provision called the Pease Limitation, which added a surcharge for some taxpayers, and reformed the alternative minimum tax (AMT), both of which reduced liability, with AMT reform making the SALT deduction available to some taxpayers for whom it was previously denied altogether.

President-elect Biden has unveiled a tax plan which, in addition to raising the top marginal rate from 37 percent to 39.6 percent, would restore the Pease Limitation and create a so-called “donut hole” where the Social Security payroll taxA payroll tax is a tax paid on the wages and salaries of employees to finance social insurance programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance. Payroll taxes are social insurance taxes that comprise 24.8 percent of combined federal, state, and local government revenue, the second largest source of that combined tax revenue. , which currently only applies to the first $137,700 of wage income, applies to all further marginal income above $400,000 as well.[34] His campaign has also signaled willingness to consider lifting the SALT cap, instead subjecting the deduction to a 28 percent overall cap, though this is not part of his official plan and would necessitate further adjustments to generate the same amount of revenue.

As Table 5 illustrates, the highest marginal rate New Yorkers currently face on combined federal and state income taxes is 48.17 percent, which is actually 0.2 percentage points lower than their pre-TCJA rate and 9.98 percentage points less than what they would pay under the Biden plan (7.52 percent if the SALT deduction were restored).[35] In this respect, the TCJA actually increased New Yorkers’ capacity to pay state taxes, since the reduced SALT deduction was more than offset by the rate cut and elimination of the Pease limitation. Those also subject to New York City taxes, however, face about a 1.31 percentage-point higher top marginal rate under current law than they did pre-TCJA, but still significantly less than they would face under the Biden plan.

Table 5 shows high earners’ top marginal rates in New York City and the much lower-tax Massachusetts (5.0 percent income tax rate), a state with which New York is frequently in competition for businesses, under current law, prior law, and the Biden plan with and without a SALT deduction cap. Under the Biden plan as outlined during the campaign, the top marginal all-in rate in New York City would reach 62.03 percent.

| Combined Top Marginal Rates in New York City and Massachusetts Under Multiple Systems | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Law (TCJA) | Prior Law (Pre-TCJA) | Biden Plan | Biden Plan + SALT | |||||

| NY | MA | NY | MA | NY | MA | NY | MA | |

| Federal Income Tax Rate | 37.00% | 37.00% | 39.60% | 39.60% | 39.60% | 39.60% | 39.60% | 39.60% |

| Medicare Taxes (Employee) | 2.35% | 2.35% | 2.35% | 2.35% | 2.35% | 2.35% | 2.35% | 2.35% |

| Social Security Donut Hole | — | — | — | — | 6.20% | 6.20% | 6.20% | 6.20% |

| Pease Limitation | — | — | 1.188% | 1.188% | 1.188% | 1.188% | 1.188% | 1.188% |

| Effective State Rate | 8.82% | 5.00% | 5.33% | 3.02% | 8.82% | 5.00% | 6.35% | 3.60% |

| Effective City Tax Rate | 3.876% | — | 2.341% | — | 3.876% | — | 2.791% | — |

| State-Only Effective Rate | 48.17% | 44.35% | 48.40% | 46.09% | 58.16% | 54.34% | 55.69% | 52.87% |

| State and City Effective Rate | 52.05% | 44.35% | 50.74% | 46.09% | 62.03% | 54.34% | 58.41% | 52.87% |

| NY / MA Tax Differential | 7.70% | 4.65% | 7.70% | 5.54% | ||||

| Source: Tax Foundation calculations. | ||||||||

While the TCJA yielded lower combined federal and state rates (but somewhat higher rates for those also subject to New York City taxes), by reducing the subsidy for high state and local taxes, it also accentuated the difference between states’ tax regimes. New Yorkers’ federal and state tax burdens are lower than they were previously—but the marginal rate differential between Massachusetts (to choose just one example) and New York rose by more than 1.5 percentage points. For New York City taxpayers, the tax differential with Massachusetts has risen from 4.65 to 7.7 percent.

Were Biden’s plan implemented, the combination of a higher rate, the restored Pease limitation, a Social Security donut hole payroll tax, and (assuming its inclusion for sake of argument) a larger but not unlimited SALT deduction would yield higher combined rates than New Yorkers saw either before or after implementation of the TCJA—58.41 percent, compared to 52.05 percent now and 50.74 percent under prior law. (Without the benefit of an uncapped SALT deduction, the Biden plan would increase New York City taxpayers’ top marginal rate to 62.03 percent.) The taxpayers’ marginal cost of living in New York rather than another state, however, would shrink somewhat compared to current law.

Should the Biden plan plus an uncapped SALT deduction, or something like it, become law, it will be tempting for state lawmakers to say that there is room to raise taxes because the SALT cap has been restored. It is important to be clear on what this means. It emphatically does not mean that federal burdens are lower, giving states the ability to raise rates to restore the status quo ex ante. Instead, it means that taxpayers’ burdens would be higher, but that the benefit of outmigration would be moderately lower—at least assuming that taxpayers only care about relative gains, and that aggregate levels do not give them sticker shock and provide the impetus for a move. If the concern is that combined federal taxes are already high, a plan which would increase those burdens would be a curious justification for raising New York’s taxes as well, even if the relative increase in other states’ burdens is even higher.

The Cuomo administration is, therefore, right to acknowledge that a capped SALT deduction means that the entire cost of higher income tax rates will be borne by New York taxpayers,[36] though the effect is not as pronounced as the governor has sometimes cautioned.[37] It would be a mistake, however, to conclude that only the SALT deduction cap matters. If, under policies implemented in the Biden presidency, high-income New Yorkers face higher federal taxes than they did either pre- or post-TCJA, an increase in state taxes will have an even more profoundly adverse economic effect and could accelerate outmigration even if the relative differences between states are slightly attenuated. That is particularly true if the cost of leaving has declined as workforces become more mobile.

New York’s Convenience Rule and the Future of Remote Work

Should remote work remain at elevated levels even after the pandemic subsides, New York will have a short-term revenue advantage over many of its peer states—albeit one that may come under increasing legal and political scrutiny, and one which may backfire in the long term, chasing employers out of the state. The policy in question is a relatively obscure one, an income tax sourcing rule called the “convenience of the employer” rule which has the effect of sourcing an employee’s income to New York if her office is located in-state, even if she conducts most or all of her work elsewhere.[38] As firms increasingly position themselves to be friendly to remote work, the effect of this policy could easily shift from one of maintaining revenues even as employees disperse to one of driving employers out of state as relocation becomes more attractive for their employees’ tax burdens as well as their own. Firms which remain, moreover, may find it more difficult to attract and retain talent.

Under most state systems, protections exist to avoid double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. when a taxpayer earns income in more than one state. A taxpayer’s domiciliary state—the place where they live—begins with a baseline of taxing all income from all sources, whether earned there or elsewhere, while other states may tax that individual on income earned within their borders. Domiciliary states then provide a credit for taxes paid to other states (frequently, but not always, capped at the amount the taxpayer would have paid on that income in their home state), avoiding double taxation.

If, for instance, a Mainer earned half her income in Vermont, her Maine taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. would include income earned in both states, while her Vermont taxable income would be half that amount. Maine would then give her a credit for the amount she paid in Vermont, ensuring that tax owed is never more than the higher of the two states’ rates on any given income stream. That, at least, is how it is supposed to work. New York and six other states with convenience rules (or similar sourcing rules) complicate things substantially, to the detriment of taxpayers.

Under so-called convenience rules, an employee is treated as if they work in their employer’s state if their work is performed elsewhere for what is termed the “convenience of the employer”—but convenience is defined very broadly, and the exceptions tend to be quite narrow. States have not always done a good job of spelling out what is meant by “convenience,” but generally the only exceptions are for when an employee’s work legitimately could not be carried out in the employer’s state.

For example, a technician servicing a New York company’s products in Vermont could not, by definition, do her job in New York, so that is not for the convenience of the employer. But a financial advisory firm’s work theoretically could be performed in the employer’s state, no matter how inconvenient or even impossible that might be for a given employee. New York and other states with convenience rules claim that income even if the employee never sets foot in the state.[39]

The convenience rule, by sourcing income to New York based on an office location, can deny taxpayers the ability to avail themselves of other states’ credits for taxes paid to other states, since, from the standpoint of those states, the taxpayer both lived and worked in their state. A company which authorizes telework, while based in New York, could frequently see its employees subject to two different state income taxes, with no offsets.

When this does and does not happen is complex and varies based on states’ interpretations and applications of their laws. Some statutes, like Vermont’s, are explicit: for a taxpayer to merit the credit, the income must be earned while physically present in the other state. Most other state statutes are silent on this point; nothing in, say, Rhode Island law expressly spells out what is required for income to be determined to be derived from New York.

Generally, however, the taxpayer’s domiciliary state is likely to assert that income earned while both living and working in their state is rightfully theirs to tax, concluding that just because an employee’s office is in another state does not mean that her income is “derived from sources outside the state.” So when a state with a convenience rule steps in and asserts the right to tax it as well, the result is double taxation.

The following table outlines three scenarios to demonstrate how tax liability is affected by convenience rules. In the first instance, a taxpayer commutes into a New York office from a New Jersey residence, with the income earned from employment in New York included in both states’ bases, but with New Jersey offering a credit that wipes out liability. In the second scenario, the New Jersey resident conducts all her work remotely in New Jersey, even though her business maintains an office in New York (and she is not assigned to an office somewhere else). In this case, she is denied New Jersey’s credit, and is exposed to double taxation. Finally, we imagine a scenario in which New York repeals its convenience rule; here, the taxpayer pays taxes to New Jersey, but not to New York.

| Commute Into New York Office from New Jersey | New Jersey Remote Work with Convenience Rule | New Jersey Remote Work without Convenience Rule | |

|---|---|---|---|

| New York Liability | $5,458 | $5,458 | $0 |

| New Jersey Pre-Credit Liability | $4,182 | $4,182 | $4,182 |

| New Jersey Tax Credit | ($4,182) | $0 | $0 |

| Total Liability | $5,458 | $9,640 | $4,182 |

| Sources: State tax schedules; Tax Foundation calculations. | |||

Crucially, this is, in 2020, a hypothetical where New Jersey is concerned. The Garden State has temporarily waived several nexus and income tax sourcing rules for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic, and is allowing taxpayers who normally commute into New York to retain the benefit of the credit for taxes paid to other states even if they no longer actually commute to New York.[40] This is a generous, taxpayer-friendly policy that avoids double taxing residents by forgoing tax revenue to which New Jersey has a far stronger claim than New York does. It is, however, a temporary policy. Once the pandemic subsides, a remote worker based in New Jersey would face double taxation if her office were located in New York, as was the case before the pandemic.

A New Yorker might well ask why he should care: even if the outcome is unfair to remote workers who reside outside the state, it is certainly consistent with the late Sen. Russell Long’s dictum (“Don’t tax you, don’t tax me, tax that man behind the tree!”),[41] and with the general popularity of exporting taxes to nonresidents. The potential concerns are twofold: one, that the tax regime might end abruptly either through federal legislation or an adverse court ruling, and two, that over time, it will drive businesses out of state.

New York’s convenience rule has existed for years, but its significance will be much greater as businesses continue to embrace telework even after it is possible for all workers to return to their offices. It is increasingly likely that companies’ unplanned experiment in telework will yield a long-term shift in how we conceptualize the workplace. In March and April alone, over 420,000 people left New York City.[42] Through October, nearly 300,000 households—not individuals—have filed change-of-address forms designating a new address outside the city,[43] a statistic that almost certainly understates the extent of the exodus. Some of those who left may never return.

In the short term, New York and the six other states with such rules[44] will be tempted to maintain them to stave off revenue declines as workers relocate elsewhere. Such rules, however, render states incredibly unattractive for businesses that wish to develop a remote work culture. By locating their offices in such a state, businesses can expose many of their employees to double taxation. This becomes an incentive to locate (or relocate) elsewhere.

Convenience rules sever whatever tie exists between a tax and the government services it funds. While most taxes (unlike some fees) fund a broad array of services and cannot be understood as a strictly user-pays arrangement, there is at least some connection between the taxpayer and the expenditure of the funds. Taxpayers pay for the governance of the area where they work—a place from which they derive some direct benefit. Taxing people who never set foot in a state, under a vague and inconsistently applied notion that they are availing themselves of the state’s market simply because their company has an office there, has scant justification.

States have broad latitude to tax in-state activity as they wish, subject to a few constitutional constraints. Aggressive tax structures which seek to tax activity that takes place wholly or almost entirely beyond the state’s borders, however, represent bad tax policy, raising constitutional questions and, as their salience increases, drawing greater attention from federal lawmakers and peer states that might be willing to challenge these rules in court.[45] New Hampshire has already entered a motion for leave to bring suit against Massachusetts before the U.S. Supreme Court over the latter’s sourcing rules[46]—a case in which any adverse ruling would also implicate New York’s regime—and a bipartisan New Jersey bill would open the door to similar litigation against New York as well.[47]

Evaluating New York Revenue Options

Some policymakers have approached the revenue question with trepidation, others with gusto. For some, the pandemic-induced revenue crunch represents an ideal time to move forward with sweeping tax policy changes; for others, it is a time for caution, balancing immediate revenue needs with the recognition that budgets can only be made whole if the economy roars back to life.

Those counseling caution have the better end of the argument. New York’s tax burdens are already the highest in the nation, with state and local taxes claiming 13.9 percent of New York personal income, compared to a national average of 9.8 percent. Even other high-tax jurisdictions like New Jersey (10.8 percent), Connecticut (10.7 percent), and Illinois (10.6 percent) are below New York levels of taxation.[48] New Yorkers’ capacity for higher taxes is not unlimited, and sensitivity to tax burdens has doubtless increased as remote work becomes considerably more feasible.

New York has netted a loss of nearly a million residents the most recent seven years for which data are available, reducing annual AGI by more than $50 billion (5.4 percent). By the standards of most of the rest of the country, these are staggering losses. New York has endured them for now, buoyed by the sheer size and vigor of its economy. The potential losses now, as businesses and individuals decide whether to return to New York, and in what capacity, could dwarf prior outmigration, and aggressive new taxes could put a thumb on the scale for some taxpayers considering their options—typically those with the largest contributions to the state’s coffers.

The remainder of this publication reviews a range of tax proposals—some with promise, others deeply fraught. Policymakers face difficult choices in the months and years ahead, but whatever decisions are made, it is important that they are reached in light of a serious analysis of the effect of proposed tax changes on the state’s competitive standing. That competitive standing has never been more important.

Mark-to-Market Taxation of Capital Gains Income

Some state lawmakers, led by Sen. Jessica Ramos (D), have proposed what is known as mark-to-market taxation of capital gains income. The so-called “Billionaire Mark to Market Tax Act” (S.8277),[49] sponsored by Ramos, would treat unrealized capital gains on billionaires’ assets as taxable income, and would begin with a first-year catchup period in which all existing realized gains are taxed (with an optional 10-year payment schedule, with a 7.5 percent penalty). Proponents believe it could raise up to $5.5 billion a year, and more than four times that the first year, which is intended to capture years of previously accumulated gains.[50] The tax would have a dramatic impact on New York’s financial sector and its investor class—a highly mobile group of taxpayers.

The proposal involves an annual tax on the appreciated value of a wide range of assets, including stocks and bonds; interests in private equity or hedge funds; ownership interests in S corporations, partnerships, or other closely-held or noncorporate businesses; cash, deposits, and options; futures contracts; real property; art and collectibles; pension funds; and other assets. The tax falls on such property wherever it is sitused (it need not be in New York) if it is owned by the taxpayer, their spouse, their minor children, or any estate or trust of which they are the beneficiary. Notably, it also applies to assets held by private foundations (including charities) to which they are a substantial contributor,[51] and to gifts they give, which are taxed as if they were still owned by the taxpayer.[52]

Although it has been branded a wealth taxA wealth tax is imposed on an individual’s net wealth, or the market value of their total owned assets minus liabilities. A wealth tax can be narrowly or widely defined, and depending on the definition of wealth, the base for a wealth tax can vary. , it technically is not one, because it only taxes the increased value of assets, not the total value, each year. Nevertheless, it has enough in common with wealth taxes to replicate some of their economic pitfalls—and the legal ones as well.

New York’s state constitution categorically prohibits a wealth tax as commonly understood, providing that “[i]ntangible personal property shall not be taxed ad valorem nor shall any excise tax be levied solely because of the ownership or possession thereof, except that the income therefrom may be taken into consideration in computing any excise tax measured by income generally,” and that “[u]ndistributed profits shall not be taxed.”[53]

The entire article on state tax powers, adopted by the Constitutional Convention of 1938 and ratified by a popular vote that year, is sufficiently clear that even the most ardent proponents of wealth taxation concede that a traditional wealth tax is impossible in the state absent a constitutional amendment. Some, however, have suggested that a mark-to-market system of taxation, which would tax unrealized investment gains, could serve as a modified wealth tax, and that it would comply with the state constitution. That argument is dubious. To appreciate why, an understanding of classes of property is necessary.

At the highest level, property is bifurcated into real and personal property classes. Real property refers to land and improvements—essentially real estate and structures. Personal property is a catch-all class for everything else, though the terminology can be confusing, because “personal” does not tell us anything about the owner of the property. Both businesses and individuals possess personal property. Your television is personal property; so is a construction company’s heavy machinery.

Personal property, moreover, can be further divided into two types: tangible and intangible personal property. As the name suggests, tangible property refers to types of (non-real estate) property that can be touched and moved: machinery, equipment, vehicles, household goods, artwork, and the like. Intangible property refers to items of value that are not physical in nature—stocks, bonds, patents, or an ownership stake in a partnership, for instance. Under New York’s constitution (and the constitutions of most states), tangible property can be taxed under the property tax, but intangible property is exempt from taxation. New York and its localities cannot tax the value of intangible assets, and a wealth tax falls apart without that, since most wealth is concentrated in businesses and investments.

Proponents contend that accumulated but unrealized gains, which would be subject to taxation under the Billionaire Mark to Market Tax Act, are income, not wealth, and can be taxed as such without violating the state constitution. But while we might conceptualize them as economic income, this is a concept, not a taxable flow. Economists speak of the imputed rent the owner of a house receives from living in (and therefore gaining the benefit from) a house she owns, but no one mistakes this concept for the actual payment of rent. Similarly, the economic income associated with unrealized gains are not contemplated by the New York constitution’s authorization of income taxes, which fall on actual cash flows.[54] The constitutional gymnastics necessary to justify the tax may be enough to table it, but they are not the only concern.

Under current law—at both the national and state levels—capital gains are not taxable until a taxpayer sells an asset. Its rising (but unrealized) value on paper is not taxed. Some federal lawmakers have contemplated what is known as a mark-to-market system that taxes capital gains annually, whether or not those gains are realized,[55] though New York’s S.8277 represents the first meaningful consideration of such a proposal at the subnational level.

Mark-to-market taxation would result in a more accurate measure of fluctuations in wealth from year to year, but it is also exceedingly complex, requiring the annual valuation of assets that lack a sales price. It is also potentially quite economically damaging, necessitating the liquidation of some assets (including business investments) to pay taxes on valuation increases that are unmatched by income flows.[56] Taxpayers are obligated to remit actual taxes on paper gains.

It is important to note that mark-to-market taxation does not change the ultimate taxability of capital gains; it changes the timing of that taxation. But time is money—literally. Under the current deferral-based system of capital gains taxation, taxpayers benefit compared to a mark-to-market system where they must pay on gains more quickly. Additional revenue from such a proposal, therefore, is not due to taxing what was once untaxed, but by accelerating payment and benefiting from the time value of money. J. Wellington Wimpy would gladly pay you Tuesday for a hamburger today; some New York lawmakers, by contrast, would gladly accept your payment today for a gain realized years or even decades from now.

Consider an investment which appreciates at a constant rate of 5 percent a year for 20 years, producing $100 million in capital gains income,[57] and assume New York’s 8.82 percent rate applies to all that income. Under both systems, the taxpayer remits $8.82 million in tax—8.82 percent of the $100 million in gains. But under deferral, the entire amount is remitted in year 20, whereas under mark-to-market, payments are made every year. In present value, mark-to-market payments are worth $1.84 million more to the state than a single payment upon realization in 20 years.[58]

In one important respect, taxing capital gains at ordinary income tax rates already overtaxes these gains, particularly under a mark-to-market regime, because inflation is included in gains. At an inflation rate of 2 percent per year, for instance, the real rate of return on this hypothetical investment would only be 3 percent, but all 5 percent would be taxed. Deferral is a counterweight to the effects of inflation.

This hypothetical, at least, involves an asset with measurable appreciation. It is rarely that simple. Even with publicly traded assets, ownership through trusts and holding companies can complicate valuation, but privately held business assets, artwork, and other items in the portfolios of the wealthiest New Yorkers defy easy valuation. Nationally, publicly traded assets only account for one-fifth of the assets held by the top 1 percent, while private business assets account for more than half.[59] The lopsidedness would be even more acute when limited to New York’s roughly 120 billionaires. The value of many privately held businesses is unknown until they are sold.

Take a recent example from the tech world, where PayPal acquired an online coupon-clipping company called Honey in 2019. Before its acquisition, the 200-person company had raised about $41 million in venture capital and was likely generating good, if not necessarily phenomenal, income for its founders. After the acquisition, its two cofounders and two other high-ranking employees split $4 billion.[60] The co-founders are both billionaires now, but would anyone have valued their assets at anywhere near that level prior to the sale? And if they had, how would the owners have been able to pay?

The assessment process would, therefore, be highly speculative and legally contentious. Even the federal government would struggle with the task. When the Joint Committee on Taxation analyzed such a proposal, it observed the magnitude of the challenge: “Many mandatory convertible securities may not have a readily ascertainable fair market value, e.g. where they are not actively traded on an exchange. Determining a value at which to mark the securities to market each year could present challenges for both taxpayers and the IRS in those circumstances.”[61]

Taxing unrealized income, moreover, can easily disrupt the source of that income. When an asset is taxed upon realization, the realization event itself produces liquid assets from which the tax can be paid. Even taxing unrealized gains from publicly traded assets is relatively straightforward, since some portion of the shares could be sold in satisfaction of tax liability. (This would, of course, still have consequences for some wealthy investors who are trying to maintain a controlling interest, and conflicting treatment of capital gains at the federal and state levels would create confused incentives.) But with private business assets, the tax can be much more consequential: some portion of the company or its assets may have to be sold to pay taxes on gains that only exist on paper. The owners are asset rich but cash poor.

Such a highly complex, costly tax will undoubtedly change behavior. Research indicates that the long-run elasticity of capital gains with respect to taxation is between -0.6 and -0.79, meaning that a 10 percent increase in tax rates on capital gains would lead to an approximately 7.9 percent reduction in capital gains.[62] If proponents’ revenue estimates are correct (and they may be seriously inflated), they would represent more than a doubling of capital gains effective rates on actual realizations.[63] In addition to potentially changing investment decisions and reducing the overall amount of capital invested (cutting into future taxable returns), the tax could easily drive some of New York’s wealthiest taxpayers out of state—depriving the state of their existing income tax payments (including on capital gains), along with other taxes they remit, ultimately including estate taxes in many cases.

No tax system anywhere in the world has ever used mark-to-market taxation. New York is often an innovator, but implementing such a system at the state level would be incredibly daunting and economically uncompetitive even if it did not raise major constitutional concerns.

Stock Transfer Tax

For over two centuries, a single street has been almost synonymous with the financial sector. Wall Street is more than a street; it is a metonym for the entire American financial services industry. It is, nevertheless, still a street, a stretch of real estate incorporating the New York Stock Exchange, major investment banks, and other financial services companies. For years, however, conceptual Wall Street has burgeoned beyond the bounds of geographic Wall Street—and a stock transfer tax, which has generated interest in some quarters, could strike a heavy blow against New York’s centrality in the financial sector.

Legislation introduced by Assemblyman Phil Steck (D) and Sen. James Sanders (D)—A.7791 and S.6203, respectively—would revive a long-abandoned stock transfer tax at rates of up to 5 cents per share (1.25 cents for stocks worth less than $5), intended to raise as much as $13 billion per year. This could easily drive trading out of New York and deal a devastating blow to the state’s financial sector, which powers so much of the New York economy.

New York’s position as a global financial capital is rooted in the geographical and political advantages of 18th and 19th century markets. Such advantages build on themselves, and New York is an undisputed beneficiary of two centuries of agglomeration effects. Even a few decades ago, it would have been almost unthinkable to operate major parts of the global financial services industry outside a few major cities like New York, London, and Shanghai. But the world has changed.

In an increasingly interconnected global economy, where financial transactions can be processed anywhere and traders can work any place with a sufficiently fast internet connection, the importance of the major exchanges being located in New York City has attenuated. Given enough of a push, they could relocate—to Chicago, to Boston, to Denver, to anywhere, really.

The major exchanges have already signaled their willingness to relocate servers from New Jersey to some other state to avoid a proposed New Jersey tax on the digital processing of the transaction. Moving the exchanges entirely is a more serious undertaking, but not an unrealistic one. There are costs to moving: transition costs, certainly, to say nothing of the appeal of New York City for many of the industry’s high earners. Yet whereas it was once almost unfathomable that the financial services industry could operate from other locales, the industry’s need of New York City is clearly in decline.

The same cannot be said for New York’s (city or state) need of the financial services industry, which directly employed 8 percent of all employees in the city and generated about 20 percent of gross city product (2015 figures)[64]. This, moreover, does not take into account the indirect contribution from jobs and industries sustained by New York’s financial services sector.