Executive Summary

Policymakers should have two priorities in the upcoming economic policy debates: a larger economy and fiscal responsibility. Principled, pro-growth taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. policy can help accomplish both.

Congress is staring down the expiration of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), and Tax Foundation is prepared to provide insight and analysis on the policies at stake. Since its enactment in 2017, the Tax Foundation team has studied the TCJA’s underlying construction and resulting strengths and weaknesses. We have also analyzed fundamental reforms that would dramatically improve the U.S. tax system to support economic growth as well as greater efficiency and simplicity.

Whether lawmakers target fundamental tax reform or follow the outline of the TCJA, they will confront decisions on what to prioritize in this forthcoming round of tax reform. In that regard, staying within the overall TCJA construct, the Tax Foundation team has analyzed difficult, but revenue-neutral ways to build a pro-growth set of reform options that would not significantly worsen the deficit once changes to the economy are considered or substantially change the distribution of the tax burden across the income scale.

The alternative reform options outlined in this paper may not be politically popular, but they would grow the economy and provide sufficient revenue to avoid significantly increasing our nation’s debt. The two alternative options would further broaden the tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. for individual income (more so than the TCJA), maintain much of the individual rate cuts from that law, improve the business tax base to support investment, and maintain the corporate tax rate of 21 percent.

Both reform options would provide working families and businesses with more long-term certainty than the current expiring tax code and remove many of the tax code’s special interest provisions.

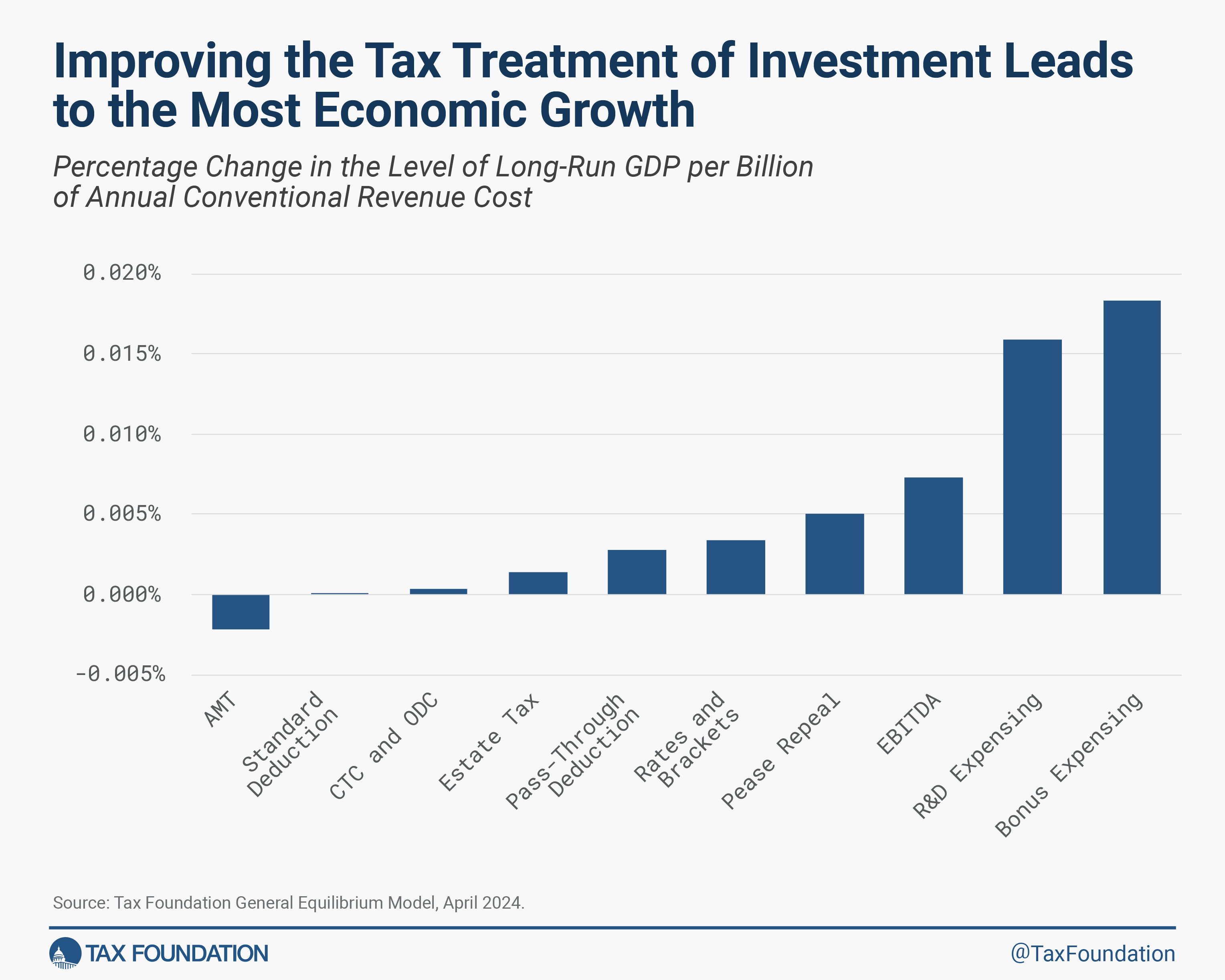

The options prioritize provisions that have the largest “bang for the buck,” or the most economic growth per dollar of revenue loss. These include immediate cost recoveryCost recovery is the ability of businesses to recover (deduct) the costs of their investments. It plays an important role in defining a business’ tax base and can impact investment decisions. When businesses cannot fully deduct capital expenditures, they spend less on capital, which reduces worker’s productivity and wages. for investments in the types of machinery and equipment upon which millions of small and large businesses depend, as well as immediate write-offs for investments in research and development. These two policy changes support a growing economy like no other tax policies proposed since the corporate tax rate was reduced from 35 percent to 21 percent. The options would also extend better cost recovery to investments that are currently excluded, resulting in more neutral tax treatment across assets.

The options in this paper show that pro-growth tax reform that does not add to the deficit requires tough choices. If lawmakers do not like the types of choices represented here, there are still other pro-growth options to achieve similar goals. Tax Foundation has modeled several alternative options over the last year. Our primary concern is not to endorse any of the specific policy options here, but to provide a resource to lawmakers so they can create sound tax policy.

With respect to the two options in this paper, the first would support an economy that is 1.4 percent larger in the long run and reduce the long-run debt-to-GDP ratio by 1.7 percentage points compared to what would happen under current law. The second option would have somewhat smaller impacts with an economy that is 0.9 percent larger and a debt-to-GDP ratio that is 0.1 percentage points larger.

Working families and businesses deserve a tax code that prioritizes growth and fiscal responsibility. This paper demonstrates multiple ways to reach those goals without substantially changing the distribution of the tax burden. These options can help Congress as lawmakers begin the difficult work of designing legislation to prevent an automatic, detrimental tax hike at the end of 2025.

Key Findings

- Unless Congress acts, the vast majority of Americans will see higher, more complicated taxes beginning in 2026 as major provisions from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 expire.

- The TCJA reduced average tax burdens for taxpayers across the income spectrum and temporarily simplified the tax filing process through structural reforms. It also boosted capital investment by reforming the corporate tax system and significantly improved the international tax system.

- If Congress fully extends the individual, estate, and business provisions, federal tax revenues would fall by more than $4 trillion on a conventional basis and by nearly $3.5 trillion on a dynamic basis over the coming decade; and without spending cuts, debt and deficits would increase.

- At a time of already high national debt, rising deficits, and higher interest rates, Congress should exercise fiscal responsibility when deciding how to extend the expiring changes.

- The decision process should be guided by promoting growth and critical principles of sound tax policy: simplicity, neutrality, transparency, and stability.

- Lawmakers must avoid economically counterproductive approaches to fiscal responsibility, such as paying for individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. cuts with higher taxes on business investment or trade.

- Tax Foundation outlines two approaches that illustrate possibilities and difficult trade-offs for designing a pro-growth and fiscally responsible extension of the TCJA without raising taxes on investment or trade.

Lawmakers Will Have to Reform the Tax Code in 2025

The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) reduced average tax burdens for taxpayers across the income spectrum by temporarily changing the structure of the individual income tax, including lower rates, wider brackets, a larger standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. It was nearly doubled for all classes of filers by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) as an incentive for taxpayers not to itemize deductions when filing their federal income taxes. and child tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. in lieu of personal and dependent exemptions, and limitations on itemized deductions. The reforms also reduced the individual income tax compliance burden by making it more advantageous for most filers to take the standard deduction and by eliminating the complexity of calculating their taxes again under the alternative minimum tax for millions of filers. Those changes all expire at the end of 2025, along with several TCJA business provisions over the next several years.

Absent congressional action, the tax system will largely revert to its previous structure, placing a higher and more complex tax burden on most people, as well as a higher tax burden on investment. Extending all the changes would greatly reduce federal tax revenue when debt is already high and deficits are rising.

As lawmakers face the challenge posed by the upcoming expirations, they should be guided by the principles of sound tax policy: simplicity, neutrality, transparency, and stability. Weighing how each provision affects individuals’ tax burdens, federal revenue, the complexity of today’s income tax system, and, most importantly, the effects of taxes on economic growth, will help prioritize which provisions should be permanent and how they should be funded.

One looming threat is that Congress will offset the cost of extending the individual tax cuts by hiking economically harmful taxes elsewhere. Several proposals have already surfaced suggesting higher taxes on corporations, investment, work, and saving to pay for continuing the TCJA’s lower taxes for individuals. Elsewhere, higher tariffs (taxes on U.S. purchases from foreign businesses) have been proposed to offset the cost of individual tax cuts. While such proposals may offset the fiscal cost of TCJA extensions, they would worsen incentives for productive activity in the United States and impose significant economic costs on the same taxpayers they purport to help. The expirations in 2025 should not be used to further riddle the tax code with distortions, redistributions, and economically harmful provisions to pay for tax breaks for some at the expense of economic growth for all.

Instead, lawmakers should use the opportunity in 2025 to further simplify and improve the tax code. Broadening the individual income tax base and ensuring permanence for better cost recovery provisions and lower tax rates would make the system more pro-growth without significantly reducing federal revenues or harming incentives to work and invest.

Ideally, tax reform would reach farther than the TCJA provisions alone. Tax Foundation has outlined several options for fundamental reform, including moving to a flat individual income tax paired with a distributed profits taxA distributed profits tax is a business-level tax levied on companies when they distribute profits to shareholders, including through dividends and net share repurchases (stock buybacks). , as other nations have successfully implemented, as well as moving to a consumption-based business profits and household compensation tax. Such reforms would go beyond the TCJA’s changes to the income tax system and move instead toward a consumption taxA consumption tax is typically levied on the purchase of goods or services and is paid directly or indirectly by the consumer in the form of retail sales taxes, excise taxes, tariffs, value-added taxes (VAT), or an income tax where all savings is tax-deductible. system. However, short of the consumption tax reform ideal, policymakers should avoid economically counterproductive tax hikes on business, trade, and investment to offset the cost of individual tax cuts. We illustrate two better options that primarily rely on base broadeners to pay for TCJA-like extensions.

The Expiring Tax Provisions

The TCJA adjusted tax bracket thresholds and widths to reduce marriage penalties and reduced five of the seven individual income tax rates. Rates fell from 10 percent, 15 percent, 25 percent, 28 percent, 33 percent, 35 percent, and 39.6 percent to 10 percent, 12 percent, 22 percent, 24 percent, 32 percent, 35 percent, and 37 percent.

The TCJA reconfigured tax adjustments for household size, shifting tax benefits toward lower- and middle-income households with roughly revenue-neutral adjustments to the standard deduction, personal and dependent exemptions, and the child tax credit (CTC). Specifically, the TCJA:

- Increased the standard deduction from $6,350 to $12,700 for singles and from $12,700 to $25,400 for married joint filers in 2018, adjusted annually for inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power.

- Increased the CTC from $1,000 to $2,000, with the maximum refundable portion increased from $1,000 to $1,400 in 2018, adjusted for inflation until it reaches $2,000; lowered the CTC phase-in threshold from $3,000 to $2,500; and lifted the phaseout thresholds from $75,000 to $200,000 for single filers and from $110,000 to $400,000 for married couples filing jointly

- Created a nonrefundable $500 credit for certain dependents who do not meet the CTC eligibility guidelines

- Suspended the personal exemption, which had previously allowed households to reduce their taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. by $4,050 for each filer and dependent, adjusted annually for inflation

To simplify the tax system and offset part of the cost of the rate reductions, the TCJA reduced itemized deductions by:

- Lowering the cap on home mortgage interest deductions from $1 million in principal to $750,000 and making interest on home equity debt nondeductible

- Introducing a $10,000 limitation on the itemized deductionItemized deductions allow individuals to subtract designated expenses from their taxable income and can be claimed in lieu of the standard deduction. Itemized deductions include those for state and local taxes, charitable contributions, and mortgage interest. An estimated 13.7 percent of filers itemized in 2019, most being high-income taxpayers. for state and local taxes paid

- Suspending miscellaneous itemized deductions such as casualty and theft losses

The TCJA also simplified the tax system by significantly reducing the number of households caught up in the alternative minimum tax (AMT) by increasing the AMT exemption and the exemption phaseout thresholds and by repealing the Pease limitation on itemized deductions.

For noncorporate businesses, the TCJA established a temporary 20 percent deduction that effectively reduced marginal tax rates by 20 percent. The pass-through deduction is subject to several complex limitations that restrict the benefit of the provision for high-income households.

The TCJA also introduced a limitation on excess business loss deductions for noncorporate businesses. It disallows losses that exceed income by more than $250,000 for single filers and $500,000 for joint filers. The thresholds adjust for inflation each year. The limitation was scheduled to be in effect from 2018 through 2025 but it was postponed to tax years beginning after 2020 during the coronavirus pandemic. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021 then extended the limitation through 2026 and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 extended the limitation through 2028.

The TCJA doubled the estate tax exemptionA tax exemption excludes certain income, revenue, or even taxpayers from tax altogether. For example, nonprofits that fulfill certain requirements are granted tax-exempt status by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), preventing them from having to pay income tax. from $5.6 million in 2017 to $11.2 million in 2018, adjusted for inflation moving forward.

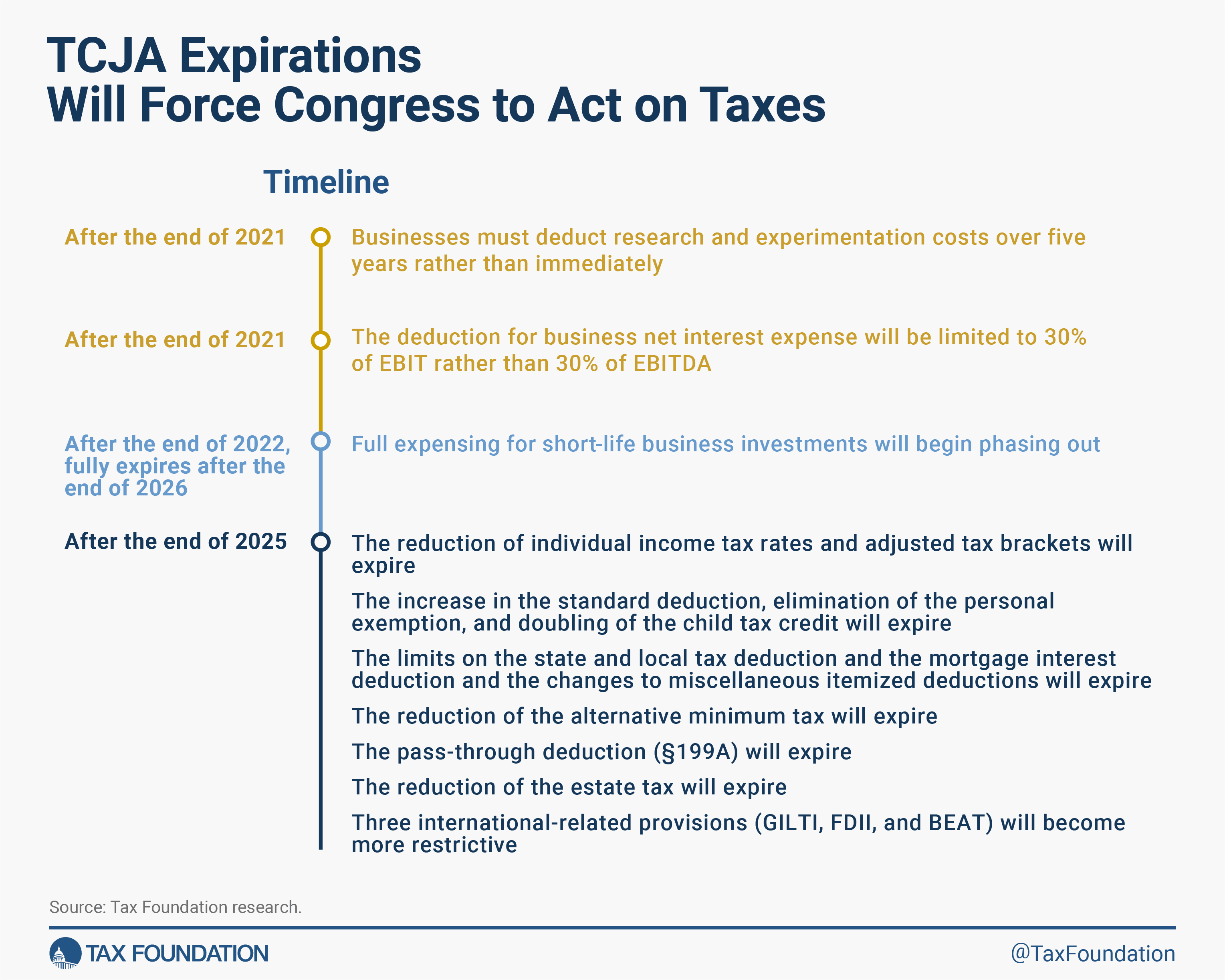

For corporate businesses, the TCJA permanently reduced the corporate tax rate to 21 percent, from a previous top rate of 35 percent.[1] The TCJA temporarily enacted full expensingFull expensing allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of certain investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings. It alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. for most short-lived business investments, such as equipment and machinery, through a provision known as 100 percent bonus depreciationBonus depreciation allows firms to deduct a larger portion of certain “short-lived” investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings in the first year. Allowing businesses to write off more investments partially alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. . The provision began phasing out by 20 percentage points each year after the end of 2022 and will fully expire after the end of 2026.

To offset the long-run cost of the lower corporate tax rate, the TCJA introduced requirements to amortize research and development (R&D) expenses over five years for domestic R&D and 15 years for foreign-sited R&D beginning in 2022 and limit deductibility of interest expenses initially based on earnings before interest, taxes, depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. , and amortization (EBITDA). Since 2022, the interest limitation has become significantly tighter due to a switch from EBITDA to earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT).

R&D amortization, tighter limits on interest deductions, and the phaseout of bonus depreciation are all policies put in place by the TCJA to reduce or offset the cost of the corporate provisions.

Making the TCJA permanent thus entails restoring the individual, noncorporate, and estate taxAn estate tax is imposed on the net value of an individual’s taxable estate, after any exclusions or credits, at the time of death. The tax is paid by the estate itself before assets are distributed to heirs. reforms as well as 100 percent bonus depreciation, R&D expensing, and the EBITDA-based interest limitation.

Economic and Revenue Effects of TCJA Permanence

In all, making the TCJA permanent would boost long-run GDP by 1.1 percent and employment by 913,000 full-time equivalent jobs, while reducing revenue by $4.0 trillion on a conventional basis. Though TCJA permanence would be pro-growth, it would still result in significant revenue losses on a dynamic basis, amounting to $3.5 trillion over the 10-year budget window. In the long run, TCJA permanence would increase the debt-to-GDP ratio by 25.5 percentage points conventionally and 19.0 percentage points dynamically.

Table 1. Economic and Revenue Effects of Continuing the TCJA

| Long-Run GDP | +1.1% |

| Long-Run Capital Stock | +0.9% |

| Long-Run Wages | +0.3% |

| Long-Run Full-Time Equivalent Employment | +913,000 |

| Conventional Revenue, 2025-2034 | -$4,047.3 |

| Dynamic Revenue, 2025-2034 | -$3,466.4 |

| Conventional Long-Run Change in Debt-to-GDP | +25.5 percentage points |

| Dynamic Long-Run Change in Debt-to-GDP | +19.0 percentage points |

TCJA permanence would increase after-tax incomes across all income groups on a conventional and dynamic basis. In 2026, taxpayers would see an average increase of 2.9 percent in their after-tax incomes; the bottom quintile’s increase would be slightly below the average at 2.2 percent while the top quintile would be above the average at 3.4 percent.

At the end of the budget window, the average increase in after-tax incomes would be 2.3 percent, slightly smaller because the one-time increase in revenue costs from transitioning to better cost recovery would have faded. On a dynamic basis, after-tax incomes would increase by 3.0 percent on average.

Because TCJA permanence would be a substantial tax cut, all income groups would see increases in their after-tax incomes, on average, on a conventional basis. In addition to the tax cuts, because TCJA permanence would increase economic output, taxpayers across the income spectrum would see higher pre-tax incomes on a dynamic basis under the larger economy.

Table 2. Distributional Effects of Continuing the TCJA (Percent Change in After-Tax Income)

| Income Group | 2026 Conventional | 2034 Conventional | Long Run Dynamic |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0% - 20.0% | 2.2% | 1.5% | 2.3% |

| 20.0% - 40.0% | 2.2% | 1.5% | 2.3% |

| 40.0% - 60.0% | 1.9% | 1.8% | 2.5% |

| 60.0% - 80.0% | 2.2% | 1.9% | 2.6% |

| 80.0% - 100% | 3.4% | 2.6% | 3.3% |

| 80.0% - 90.0% | 2.1% | 1.8% | 2.5% |

| 90.0% - 95.0% | 2.6% | 2.3% | 3.1% |

| 95.0% - 99.0% | 4.4% | 3.6% | 4.3% |

| 99.0% - 100% | 4.8% | 2.8% | 3.6% |

| Total | 2.9% | 2.3% | 3.0% |

Analyzing the TCJA’s Bang for the Buck

Altogether, we estimate the 10 tax cuts (lower rates and brackets, larger standard deduction, larger child tax credit and other dependent credit, the pass-through deduction, Pease limitation repeal, AMT changes, estate tax changes, EBITDA, 100 percent expensing, and R&D expensing) would reduce federal tax revenue by $7.4 trillion. The four base broadeners (SALT cap, other itemized deduction limitations, personal exemption repeal, noncorporate loss limitation) partially pay for the tax cuts by raising nearly $3.4 trillion.

Not every dollar of the $7.4 trillion in lower taxes has the same effect on economic growth or tax compliance and administration costs. The most pro-growth provision by far is permanence for 100 percent bonus depreciation, illustrating how improving investment incentives creates the most economic return for each dollar of tax revenue forgone. Indeed, recent studies have determined that the TCJA’s corporate tax reforms, including lowering the corporate tax rate and providing 100 percent bonus depreciation, significantly boosted investment in the United States.[2]

Of course, economic growth is not the only metric by which to judge a tax provision. For example, the alternative minimum tax requires taxpayers to calculate their tax liability the ordinary way, then again for AMT purposes. Taxpayers must add back several ordinary tax deductions, then subtract an AMT exemption, determine whether they are subject to the phaseout of the AMT exemption, and then calculate their tax liability under the AMT rates (of 26 percent and 28 percent) and pay whichever tax is highest.

Because the AMT rates are lower than ordinary rates, taxpayers caught up in the alternative system face lower marginal tax rates, but they also face a much higher compliance burden and potentially higher average tax rates. Past IRS estimates indicate an average compliance burden of more than 12 hours per taxpayer subject to the AMT, and the TCJA’s changes reduced AMT filers from 5 million in 2017 to 244,000 in 2018.[3] Likewise, the TCJA’s larger standard deduction, combined with limitations on itemized deductions, further simplified the tax system by reducing the number of filers who itemize their deductions. The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated the number of itemized filers would decline from 46.5 million in 2017 to just over 18 million in 2018, implying nearly 30 million households would find it more advantageous to take the standard deduction.[4]

On the other hand, some tax cuts, such as the pass-through deduction and the more generous deduction for interest expenses, increase economic growth but raise other concerns regarding neutrality and simplicity. For example, the argument for including the pass-through deduction, which reduced the tax rates faced by noncorporate businesses, in the TCJA was to achieve parity with the rate reductions C corporations received. But rather than parity, estimates of effective tax rates by business type show that noncorporate businesses face lower marginal tax rates than corporate businesses, in large part due to the pass-through deduction.[5]

Limiting interest deductibility continues to be a worthwhile policy goal, as it moves the tax base closer to one on consumption and scales back the tax bias for debt over equity.

Accordingly, considerations in addition to growth, including the effects on complexity, compliance costs, and administrative costs, should guide lawmakers as they consider what to include in a tax reform package.

Alternatives for Extending the TCJA

In 2025, lawmakers will debate how to prioritize better cost recovery for business investment, lower individual rates and a broader tax base, and changes to family provisions. Tax Foundation believes a top priority should be to craft a tax reform package that prioritizes economic growth and moves the tax code toward simplicity, transparency, neutrality, and stability.

The first alternative we model, i.e., Option 1, focuses on the policies changed by the TCJA. It starts with permanence for 100 percent bonus depreciation and R&D expensing and expands better cost recovery to structures with the policy of neutral cost recovery. Neutral cost recovery would retain the current depreciation schedules for structures (27.5 years for residential real estate and 39 years for commercial real estate) but would augment the depreciation deductions with adjustments for inflation and the time value of money. In real terms, the neutral cost recovery adjustments hold companies harmless for having to wait to take deductions. Option 1 also eliminates all green energy tax credits and the newly enacted 15 percent corporate alternative minimum tax (CAMT).

For individual income taxes, Option 1 retains the TCJA’s CTC and personal exemption changes. It expands the standard deduction, reduces tax rates, and alters tax bracketsA tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. , but all to a slightly smaller degree than the TCJA to reduce the revenue cost of the tax reductions.

To offset the cost of the reductions, Option 1 fully eliminates all Schedule A itemized deductions, which also significantly simplifies the structure of the tax. Building on the simplification, it fully eliminates the individual AMT. To reduce marriage penalties, it sets the head of household brackets and standard deduction equal to single filer thresholds.

Option 1 makes the TCJA’s increase in the estate tax exemption permanent, switches the limitation on interest back to EBITDA but at a lower percentage (17 percent instead of 30 percent), and allows both the Section 199A pass-through deduction and non-corporate loss limitation to expire.

The second alternative we model, i.e., Option 2, incorporates all the changes from Option 1, then further broadens the individual income tax base by ending the income tax exclusion for employer-provided fringe benefits, most notably health insurance. The additional revenue from ending the exclusion offsets the cost of making the CTC fully refundable and further lowering individual income tax rates and widening brackets.

Both Option 1 and Option 2 illustrate the tough trade-offs lawmakers will face in 2025, even short of pursuing a more comprehensive overhaul of the entire tax system. The biggest challenge lawmakers will face is that while broadening the tax base reduces distortions and complexities and offsets the fiscal impact of rate reductions, it also imposes costs on the narrow groups of taxpayers currently benefiting from each provision.

Table 3. Comparing Major Provisions of TCJA Permanence, Expiration, and Other Options in 2026

| TCJA Permanence | TCJA Expiration | Revenue-Neutral Option 1 | Revenue-Neutral Option 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonus Depreciation | Restored | Expired | Restored | Restored |

| R&D Expensing | Restored | Expired | Restored | Restored |

| Interest Limitation | 30% EBITDA | 30% EBIT | 17% EBITDA | 17% EBITDA |

| Section 199a Pass-through Deduction | Extended | Expired | Expired | Expired |

| Noncorporate Loss Limitation | Extended | Expired (after 2028) | Expired (after 2028) | Expired (after 2028) |

| Other business provisions | Neutral cost recovery for structures Eliminate green energy credits (allow grandfathering for production tax credits) and CAMT | Neutral cost recovery for structures Eliminate green energy credits (allow grandfathering for production tax credits) and CAMT |

||

| Single Rates and Brackets, 2026 | 10% - $0 | 10% - $0 | 10% - $0 | 10% - $0 |

| 12% - $12,125 | 15% - $12,125 | 12% - $12,150 | 10% - $0 | |

| 22% - $49,450 | 25% - $49,250 | 24% - $50,000 | 20% - $52,350 | |

| 24% - $105,400 | 28% - $119,300 | 25% - $105,400 | 25% - $108,550 | |

| 32% - $201,150 | 33% - $248,850 | 32% - $201,150 | 32% - $191,600 | |

| 35% - $255,450 | 35% - $541,000 | 35% - $300,000 | 35% - $255,240 | |

| 37% - $638,650 | 39.6% - $543,200 | 36% - $450,000 | 36% - $510,900 | |

| Joint Rates and Brackets, 2026 | 10% - $0 | 10% - $0 | 10% - $0 | 10% - $0 |

| 12% - $24,300 | 15% - $24,250 | 12% - $24,300 | 10% - $0 | |

| 22% - $98,900 | 25% - $98,500 | 24% - $100,000 | 20% - $104,700 | |

| 24% - $210,800 | 28% - $198,800 | 25% - $210,800 | 25% - $217,100 | |

| 32% - $402,300 | 33% - $302,950 | 32% - $402,300 | 32% - $383,200 | |

| 35% - $510,900 | 35% - $541,000 | 35% - $510,900 | 35% - $485,355 | |

| 37% - $766,350 | 39.6% - $611,100 | 36% - $766,350 | 36% - $766,350 | |

| Other individual income tax provisions | Head of household brackets set to single | Head of household brackets set to single |

||

| Standard Deduction, 2026 | $15,300 single | $8,300 single | $13,750 single and head of household | $13,750 single and head of household |

| $23,000 head of household | $12,150 head of household | $27,500 joint | $27,500 joint | |

| $30,600 joint | $16,600 joint | |||

| Personal Exemption, 2026 | $0 | $5,300 | $0 | $0 |

| 2026 CTC max | $2,000 | $1,000 | Same as TCJA | $2,100, inflation adjusted |

| Phase in | $2,500 | $3,000 | Same as TCJA | $2,500 |

| Refundability cap | $1,800 inflation adjusted | No cap | Same as TCJA | No cap |

| Phase out | $200,000 single and $400,000 joint | $75,000 single and $110,000 joint | Same as TCJA | $200,000 single and $400,000 joint |

| $500 non-refundable other dependent credit | Same as TCJA | $500 non-refundable other dependent credit | ||

| Other dependent credit | Same as TCJA | |||

| SALT | $10,000 limit | Uncapped | Eliminated | Eliminated |

| HMID | $750,000 principal | $1 million principal | Eliminated | Eliminated |

| Other Itemized Deductions | Mics. itemized deductions eliminated | Restored | All itemized deductions eliminated | All itemized deductions eliminated |

| TCJA AMT | Extended | Expired | Fully eliminated | Fully eliminated |

| Estate Tax Exemption, 2026 | $14.3 million | $7 million | $14.3 million | $14.3 million |

Permanence for the TCJA would increase the 10-year deficit by more than $4 trillion conventionally and $3.5 trillion dynamically, before added interest costs. By contrast, Option 1 and Option 2 would reduce revenue by a much smaller magnitude on a conventional basis, by $488.5 billion and $182 billion over 10 years. On a dynamic basis, both options would be approximately revenue neutral over the budget window. And though the revenue impact between TCJA permanence and the options is markedly different, both options have a positive effect on the long-run economy. Option 1 would increase long-run GDP by 1.4 percent and Option 2 by 0.9 percent. The larger economy and revenue-neutral impact on a dynamic basis together would lead to a 1.7 percentage point reduction in the debt-to-GDP ratio over the long run under Option 1 and a very slight increase of 0.1 percentage points under Option 2, measured on a dynamic basis.

Table 4. Economic and Revenue Effects of Revenue-Neutral TCJA Options

| Option 1 | Option 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Long-Run GDP | 1.4% | 0.9% |

| Long-Run Capital Stock | 1.6% | 1.1% |

| Long-Run Wages | 1.0% | 1.0% |

| Long-Run Full-Time Equivalent Employment | 494,000 | -79,000 |

| Conventional Revenue, 2025-2034 | -$488.5 billion | -$182.0 billion |

| Dynamic Revenue, 2025-2034 | +$5.2 billion | -$1.9 billion |

| Long-Run Change in Debt-to-GDP, Conventional | +5.4 percentage points | +3.9 percentage points |

| Long-Run Change in Debt-to-GDP, Dynamic | -1.7 percentage points | +0.1 percentage points |

On average, after-tax incomeAfter-tax income is the net amount of income available to invest, save, or consume after federal, state, and withholding taxes have been applied—your disposable income. Companies and, to a lesser extent, individuals, make economic decisions in light of how they can best maximize their earnings. would rise for all quintiles under both options, by 0.5 percent conventionally under Option 1 and from 0.3 percent to 0.4 percent conventionally under Option 2. Under Option 1, in 2026, the 80th to 95th percentile would see a reduction in after-tax income on a conventional basis, and under Option 2, the 80th to 99th percentile would see a reduction in after-tax incomes in 2026. On a long-run dynamic basis, all groups would see increases in after-tax income by 1.6 percent on average under Option 1 and by 1.1 percent under Option 2.

Table 5. Distributional Effects of Revenue-Neutral TCJA Options (Percent Change in After-Tax Income)

| Option 1 | Option 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional, 2026 | Conventional, 2034 | Dynamic, Long Run | Conventional, 2026 | Conventional, 2034 | Dynamic, Long Run | |

| 0% - 20.0% | 1.6% | 1.2% | 2.3% | 1.4% | 1.5% | 2.3% |

| 20.0% - 40.0% | 0.5% | 0.1% | 1.1% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.9% |

| 40.0% - 60.0% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 1.3% | 0.2% | 0.5% | 1.2% |

| 60.0% - 80.0% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 1.1% | 0.4% | 0.6% | 1.2% |

| 80.0% - 100% | 0.6% | 0.7% | 1.9% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 1.0% |

| 80.0% - 90.0% | -0.3% | -0.3% | 0.7% | Less than -0.05% | Less than +0.05% | 0.7% |

| 90.0% - 95.0% | -0.3% | -0.1% | 1.0% | -0.5% | -0.5% | 0.2% |

| 95.0% - 99.0% | 1.1% | 1.3% | 2.6% | -0.1% | Less than +0.05% | 0.8% |

| 99.0% - 100% | 2.0% | 1.9% | 3.5% | 1.4% | 1.3% | 2.5% |

| Total | 0.5% | 0.5% | 1.6% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 1.1% |

Fundamental Tax Reform Options

Even after the reforms made by the TCJA, the U.S. tax system still closely resembles a broad income tax, generally taxing a person’s current earnings (whether spent or saved) plus the change in the value of their existing assets (such as dividends, capital gains, interest, etc.). By taxing income this way, the tax system places a higher tax burden on future or deferred consumption. Taxing income also requires complicated determinations on how to define income, which increases the complexity of the tax code and makes it harder for families to file their taxes and claim certain tax benefits.

In some cases, however, the tax system adopts provisions like retirement savings accounts for individuals and investment deductions for businesses that eliminate double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. for specific forms of saving and investment. These provisions, however, are limited and complex.

Both options outlined above retain the general structure of the income tax, albeit with marked improvements such as better deductions for business investment and reduced (or eliminated) itemized deductions. Full cost recovery moves the business tax code closer to a consumption-based tax but it does not remove the tax bias against saving at the individual level.

A more fundamental reform would move away from the income tax system and replace it with a consumption tax system. Table 6 illustrates the economic, revenue, and distributional differences of two comprehensive reforms proposed by Tax Foundation.

The first proposal would replace the entire business income tax system with a 20 percent distributed profits tax resembling Estonia’s tax system and make significant reforms to individual, capital gains, and estate taxes, including a flat rate of 20 percent on individual income to match the distributed profits tax rate.[6]

The second proposal would replace the current business and individual income tax systems with a modified value-added tax, applying a 30 percent rate to destination-based cash flow of businesses and a progressive taxA progressive tax is one where the average tax burden increases with income. High-income families pay a disproportionate share of the tax burden, while low- and middle-income taxpayers shoulder a relatively small tax burden. ranging from 10 percent to 30 percent on household compensation.[7] Both reforms would significantly simplify the tax system, move toward a consumption tax base, and reduce tax penalties on work, saving, and investment. With changes to tax rates, either plan could be made more progressive and raise more revenue, with relatively smaller economic trade-offs because the tax base would be appropriately designed.

As lawmakers look to change the tax system in 2025, pursuing more comprehensive tax reform offers more significant economic and simplification benefits and can be done in a fiscally responsible manner. The distributed profits tax plan would substantially boost revenue within the budget window; in the long run, it would lose revenue on a conventional basis and be slightly revenue raising on a dynamic basis. The larger economy and increased tax revenue together would result in a reduction in the debt-to-GDP ratio of 9.2 percentage points over the long run, on a dynamic basis. The household compensation and business profits tax would lose revenue within the 10-year budget window, but would be revenue neutral on a conventional basis and revenue raising on a dynamic basis in the long run. The plan would have a small impact on the debt-to-GDP ratio over the long run, increasing it by 1.5 percentage points.

Table 6. Economic and Revenue Effects of Selected Comprehensive Tax Reform Options

| Distributed Profits Tax Reform | Household Compensation and Business Profits Tax Reform | |

|---|---|---|

| Long-Run GDP | +2.5% | +1.9% |

| Long-Run Capital Stock | +3.4% | +2.8% |

| Long-Run Wages | +1.4% | +1.2% |

| Long-Run Full-Time Equivalent Employment | 1.3 million | +886,000 |

| 10-Year Conventional Revenue | +$523 billion | -$1.0 trillion |

| 10-Year Dynamic Revenue | +$1.4 trillion | -$129.6 billion |

| Dynamic Long-Run Change in Debt-to-GDP | -9.2 percentage points | +1.5 percentage points |

Conclusion

The upcoming expirations of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act provide lawmakers the opportunity to build on what the TCJA did well and avoid some of its pitfalls. The TCJA boosted investment, simplified the tax filing process, and cut taxes for households across the income spectrum.

Rising deficits, debt, and interest rates should push lawmakers toward a more fiscally responsible approach than in 2017, but they must exercise caution when evaluating how to pay for tax cuts. The principles of simplicity, neutrality, stability, and transparency should guide the debate, and the end goal should be a tax code that is less harmful to economic growth and supports fiscal responsibility.

The best outcome would be a comprehensive reform of the income tax system toward a consumption tax system. Short of that, lawmakers should at a minimum aim to reduce tax preferences and broaden the tax base to offset the costs of TCJA extensions, rather than raising economically harmful taxes on corporations, international trade, or high-income individuals to pay for a continuation of TCJA policies. The goal of any tax reform should be to improve incentives for Americans to work, save, and invest, and to significantly simplify the complex process people face in complying with the current tax system.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe[1] The TCJA also moved the international tax system toward a territorial one by exempting foreign profits from domestic taxation and creating anti-base erosion provisions targeted at high-return foreign profits, intangible income, and income stripped out of the United States. The four main components of the new international tax system are the participation exemption, GILTI, FDII, and BEAT, and the latter three provisions are scheduled to become more restrictive after the end of 2025. A forthcoming Tax Foundation publication will discuss international tax policy options.

[2] Gabriel Chodorow-Reich, Matthew Smith, Owen Zidar, Eric Zwick, “Tax Policy and Investment in a Global Economy,” National Bureau of Economic Research, March 2024, https://www.nber.org/papers/w32180.

[3] Demian Brady, “Tax Complexity 2021: Compliance Burdens Ease for Third Year Since Tax Reform,” National Taxpayers Union, Apr. 15, 2021, https://www.ntu.org/foundation/tax-page/tax-complexity-2021-compliance-burdens-ease-again-after-tcja.

[4] The Joint Committee on Taxation, “Tables Related to the Federal Tax System as in Effect 2017 Through 2026,” Apr. 24, 2018, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5093.

[5] Kyle Pomerleau, “Section 199A and ‘Tax Parity,’” American Enterprise Institute, Sep. 12, 2022, https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/section-199a-and-tax-parity/.

[6] William McBride, Huaqun Li, Garrett Watson, Alex Durante, Erica York, and Alex Muresianu, “Details and Analysis of a Tax Reform Plan for Growth and Opportunity,” Tax Foundation, Jun. 29, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/growth-opportunity-us-tax-reform-plan/.

[7] Erica York, Garrett Watson, Alex Durante, and Huaqun Li, “How Taxing Consumption Would Improve Long-Term Opportunity and Well-Being for Families and Children,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 12, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/us-consumption-tax-vs-income-tax/.

Share this article