Federal, state, and local governments raise revenues for road infrastructure and maintenance through a combination of taxes on motor fuel, fees on vehicles like registration or licensure, and direct levies on drivers like tolls. This system constitutes a relatively well-designed user feeA user fee is a charge imposed by the government for the primary purpose of covering the cost of providing a service, directly raising funds from the people who benefit from the particular public good or service being provided. A user fee is not a tax, though some taxes may be labeled as user fees or closely resemble them. system, where roadway expenditures are largely furnished by the people who use the roads generally in proportion to the extent of their use.

However, these road taxes and fees are far from a perfect user fee, especially as inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. , electric vehicles, and fuel efficiency gains erode gas taxA gas tax is commonly used to describe the variety of taxes levied on gasoline at both the federal and state levels, to provide funds for highway repair and maintenance, as well as for other government infrastructure projects. These taxes are levied in a few ways, including per-gallon excise taxes, excise taxes imposed on wholesalers, and general sales taxes that apply to the purchase of gasoline. revenues per mile of road driven. Most states fail to collect enough in user fees to fully provide for roadway spending. This necessitates transfers from general funds or other revenue sources that are unrelated to road use to pay for road construction and maintenance.

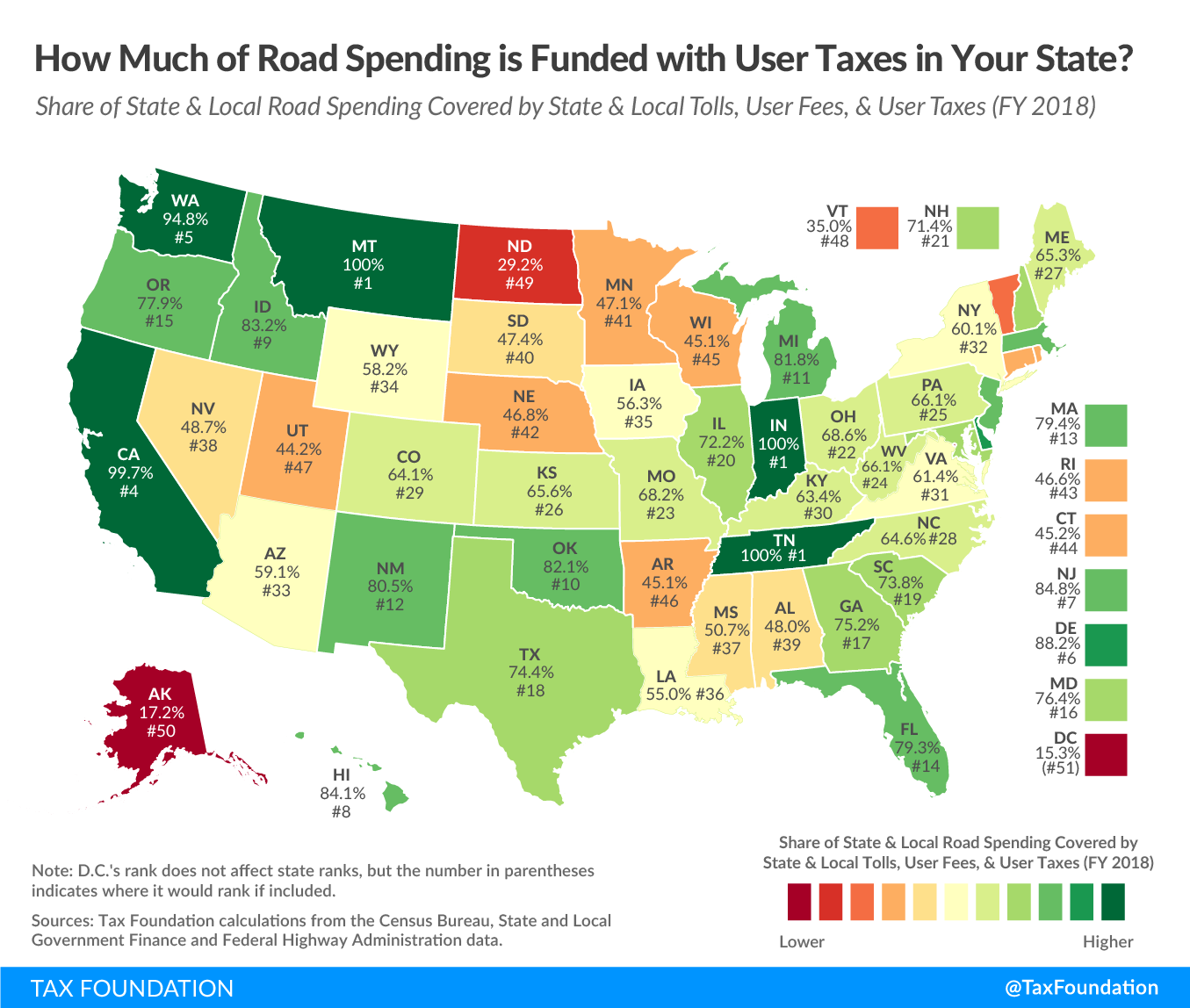

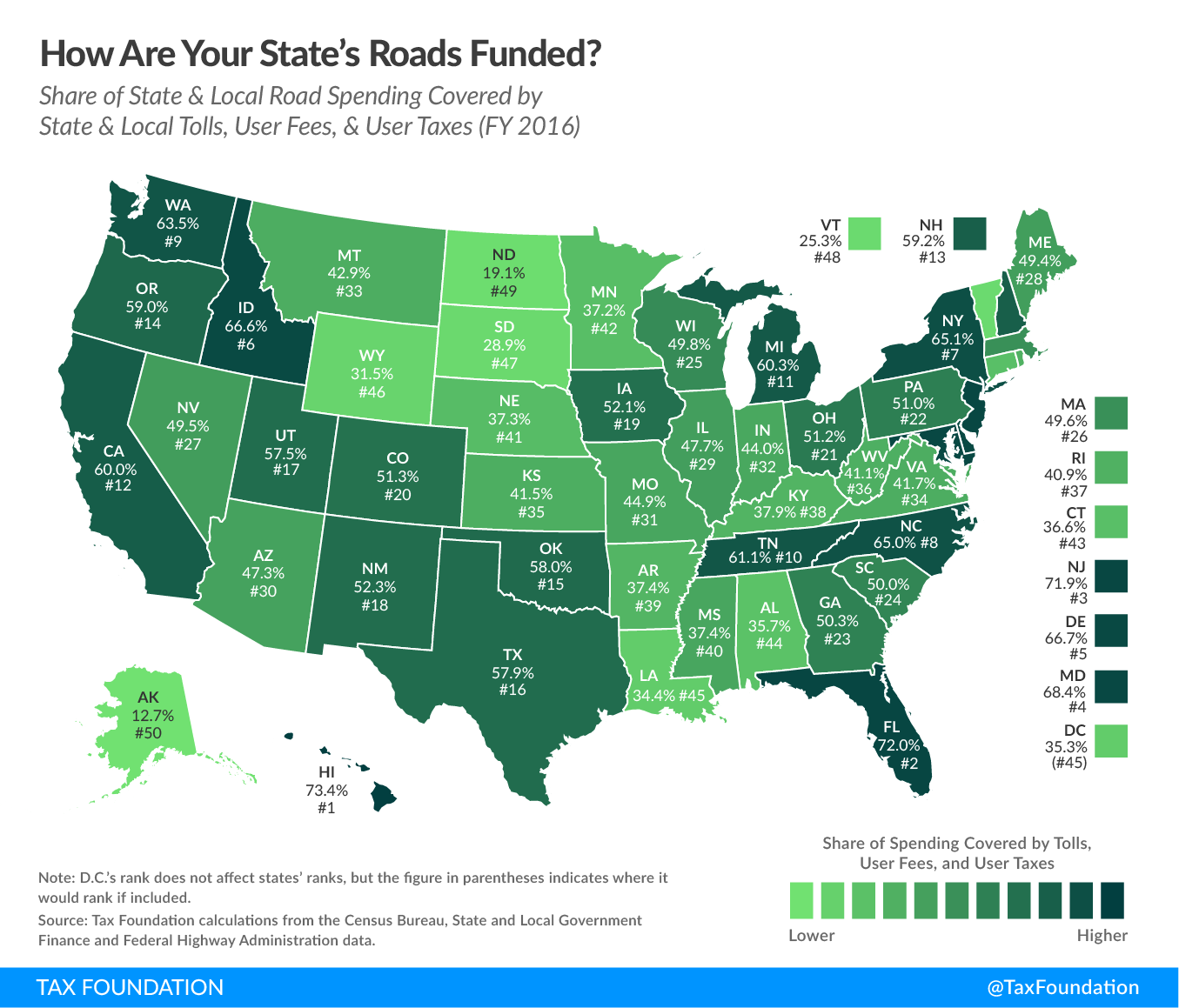

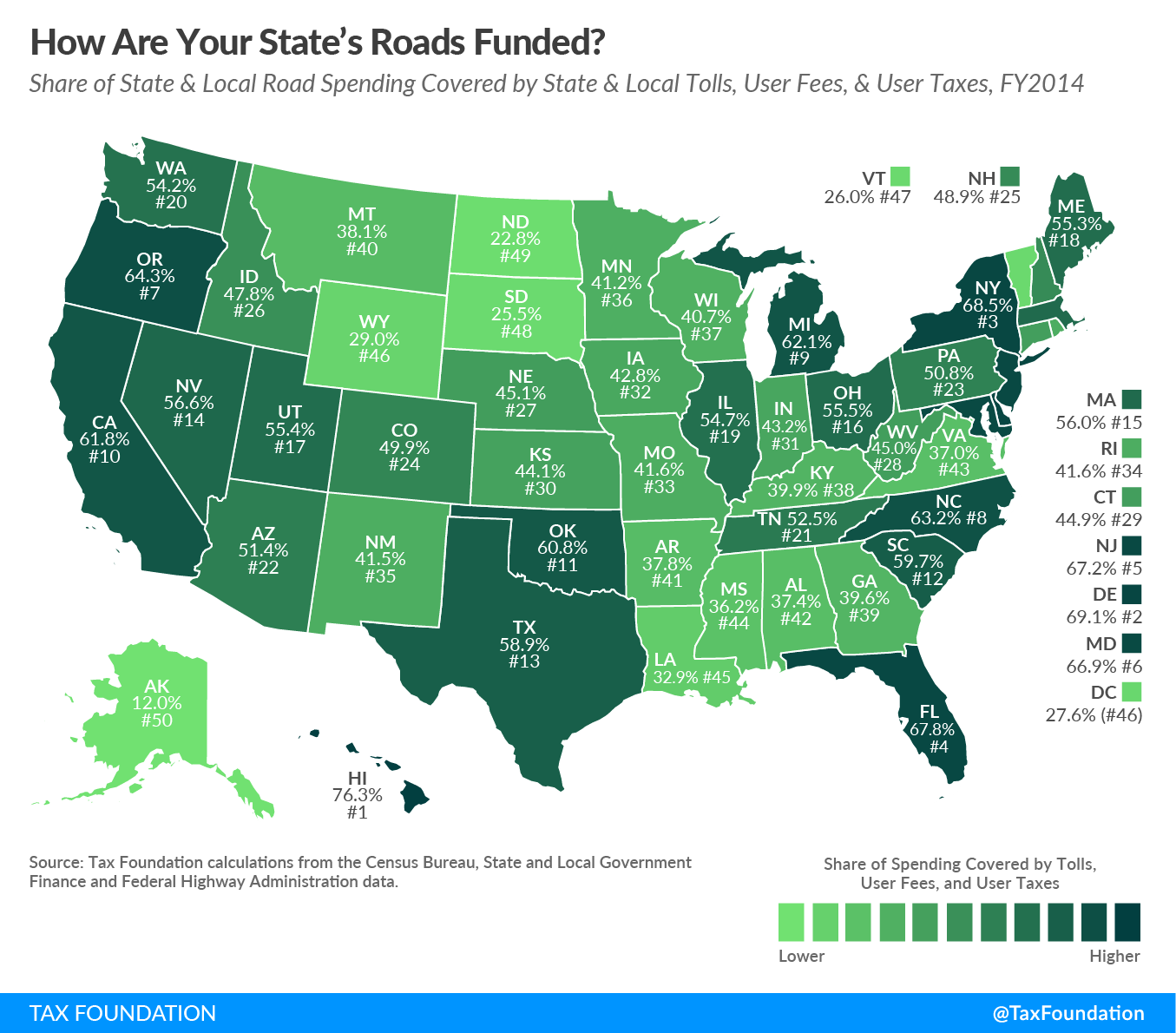

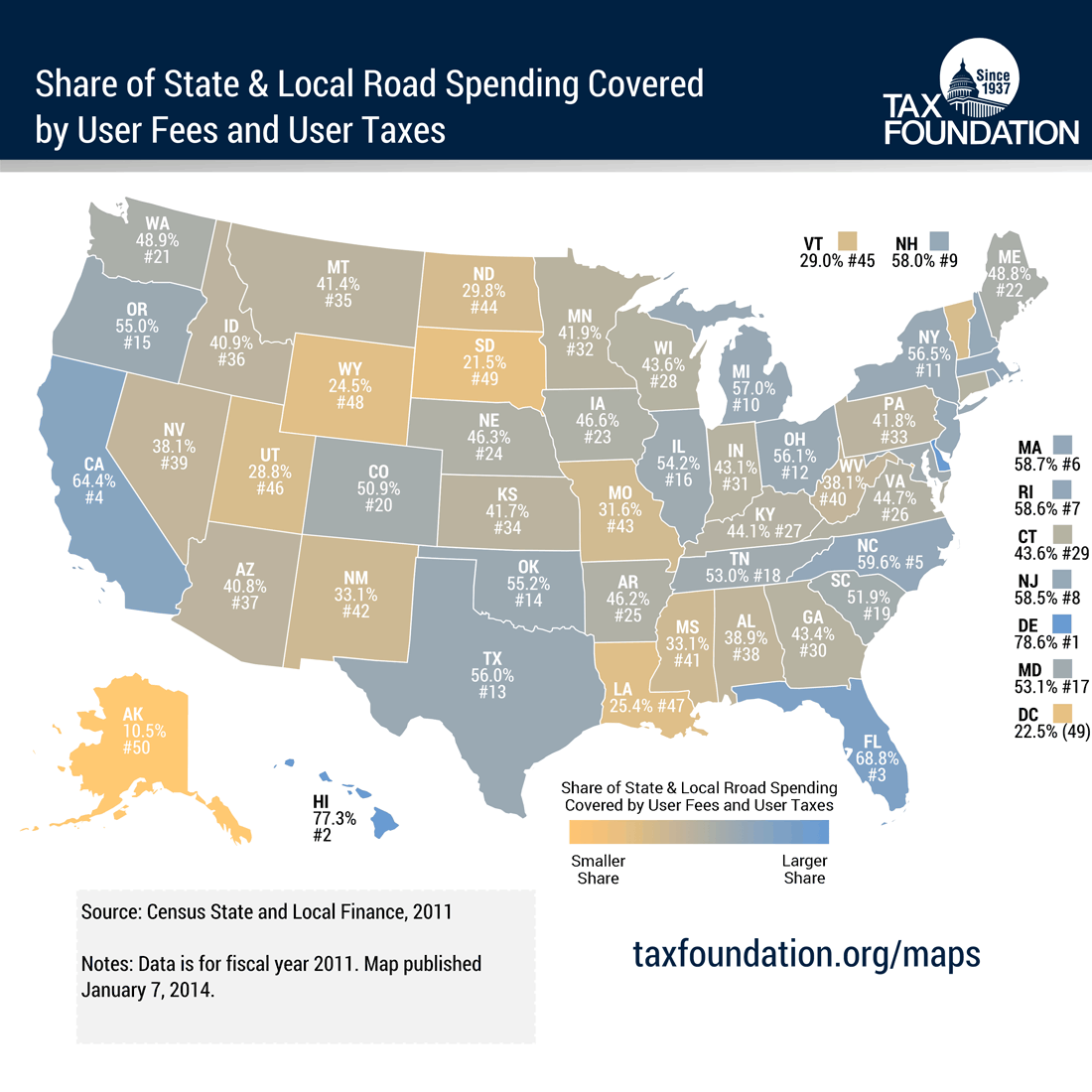

The amount of revenue states raise through roadway-related revenues varies significantly across the US. Only three states—Delaware, Montana, and New Jersey—raise enough revenue to fully cover their highway spending. The remaining 47 states and the District of Columbia must make up the difference with taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. revenues from other sources. The states that raise the lowest proportion of their highway funds from transportation-related sources are Alaska (19.4 percent) and North Dakota (35.1 percent), both states which rely heavily on revenue from severance taxes.

Road Taxes and Funding by State

Share of State and Local Spending Covered by State and Local Road Use Taxes (FY 2022)

| State | Share of State and Local Spending Covered by State and Local Road Use Taxes (FY 2022) | Rank |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 74.9% | 18 |

| Alaska | 19.4% | 50 |

| Arizona | 67.3% | 23 |

| Arkansas | 55.1% | 35 |

| California | 89.2% | 11 |

| Colorado | 58.0% | 33 |

| Connecticut | 48.7% | 41 |

| Delaware | 100.0% | 1 |

| Florida | 77.7% | 16 |

| Georgia | 58.4% | 32 |

| Hawaii | 97.2% | 7 |

| Idaho | 78.9% | 14 |

| Illinois | 95.4% | 8 |

| Indiana | 76.2% | 17 |

| Iowa | 61.6% | 31 |

| Kansas | 57.4% | 34 |

| Kentucky | 54.7% | 36 |

| Louisiana | 47.9% | 43 |

| Maine | 54.4% | 37 |

| Massachusetts | 82.2% | 12 |

| Maryland | 93.2% | 10 |

| Michigan | 64.5% | 26 |

| Minnesota | 44.1% | 45 |

| Mississippi | 52.7% | 38 |

| Missouri | 65.5% | 25 |

| Montana | 100.0% | 1 |

| Nebraska | 43.0% | 46 |

| Nevada | 52.2% | 39 |

| New Hampshire | 79.7% | 13 |

| New Jersey | 100.0% | 1 |

| New Mexico | 64.1% | 27 |

| New York | 93.8% | 9 |

| North Carolina | 68.8% | 22 |

| North Dakota | 35.1% | 49 |

| Ohio | 99.0% | 5 |

| Oklahoma | 72.1% | 21 |

| Oregon | 74.4% | 19 |

| Pennsylvania | 73.4% | 20 |

| Rhode Island | 61.6% | 30 |

| South Carolina | 99.1% | 4 |

| South Dakota | 41.6% | 47 |

| Tennessee | 97.2% | 6 |

| Texas | 65.9% | 24 |

| Utah | 41.6% | 48 |

| Virginia | 44.7% | 44 |

| Vermont | 48.3% | 42 |

| West Virginia | 52.1% | 40 |

| Washington | 78.4% | 15 |

| Wisconsin | 62.4% | 28 |

| Wyoming | 61.7% | 29 |

| District of Columbia | 18.9% | (51) |

| US | 73.0% |

Source: US Census Bureau State and Local Finances; Federal Highway Administration Highway Statistics Series 2022; Authors' Calculations

Data compiled by Jacob Macumber-Rosin , Adam Hoffer

Latest Updates

- California has increased its proportion of roadway spending furnished by road users from 72 percent to 89.2 percent.

- Hawaii has increased its proportion of roadway spending furnished by road users from 78 percent to 97.2 percent.

- Indiana has decreased its proportion of roadway spending furnished by road users from 88 percent to 76.2 percent.

- Kentucky has decreased its proportion of roadway spending furnished by road users from 74 percent to 54.7 percent.

- New Hampshire has increased its proportion of roadway spending furnished by road users from 62 percent to 79.7 percent.

- New York has increased its proportion of roadway spending furnished by road users from 71 percent to 93.8 percent.

- North Carolina has decreased its proportion of roadway spending furnished by road users from 88 percent to 68.8 percent.

- Ohio has increased its proportion of roadway spending furnished by road users from 82 percent to 99.0 percent.

Diving Deeper

Because road use fees fall short of fully funding roadway systems in most states, governments must transfer revenues from other sources to road expenditures. By diverting general funds to roadway spending, the burden of paying for the roads falls on all taxpayers, including people who drive very little or may not drive at all. By relying on other revenue sources to fund roads, states effectively underprice road use. This can manifest in several forms, most notably traffic congestion, but can also distort the transportation market by subsidizing road use relative to alternatives, particularly freight rail.

Gas tax revenues have become increasingly decoupled from road funding needs. Tax rates are often not indexed to inflation, which causes the real value of the revenues to deteriorate even without other changes.

Beyond the effects of inflation, gas taxes are losing ground as an effective proxy for road use. Motor vehicle fuel efficiency increased substantially over the past several decades meaning vehicles can drive more miles per gallon of gas consumed. This means the gas tax generates declining revenue per mile driven on roads. And electric vehicles don’t pay the gas tax at all. Whatever the benefits of electric vehicles, they still put wear and tear on roads.

The federal government is considering large one-time fees on electric vehicles in order to partially offset their lack of exposure to the gas tax and address the Highway Trust Fund’s major fiscal problems. State governments have implemented similar programs through special registration fees or taxes on charging electric vehicles to varying degrees. At both the federal and state levels, these crude patches in roadway funding holes can at best delay fiscal problems with the road funding system, as the same underlying trends would still affect road revenues despite the new influx of EV fees.

A better long-term fix would be to shift funding from increasingly inappropriate proxies for road use to a direct user fee on each mile driven, a vehicle miles traveled tax (VMT). Most states and the federal Department of Transportation have begun exploring replacing the existing funding structure with a simpler VMT tax that better aligns use with costs and better approximates the real price of roads. While states may find it difficult to shift to such a system without the federal government as first mover, state policymakers might nonetheless want to push—and prepare—for such a system. With all but three states unable fund their roadways using existing user fees, road funding is in dire need of a better system.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe