Note: The following is the testimony of Daniel Bunn, President & CEO of TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. Foundation, before the US Senate Committee on Finance hearing on September 12, 2024, titled, “The 2025 Tax Policy Debate and Tax Avoidance Strategies.”

Chairman Wyden, Ranking Member Crapo, and members of the committee, thank you for the opportunity to discuss the upcoming 2025 tax debate and tax avoidance strategies with you. My name is Daniel Bunn, and I am President of the Tax Foundation, a nonprofit think tank dedicated to studying tax policy at all levels of government.

The stakes for next year’s expiring tax provisions are quite high. If Congress does nothing, then 62 percent of filers will see their taxes go up in January of 2026. However, the proposals from both sides of the political aisle raise questions about policy design, fiscal impact, and economic results. A multi-trillion-dollar gap separates the parties’ positions on major tax policy questions.

Concerns about avoidance should be bipartisan, and, in my view, motivate policy in the direction of a simpler, more neutral tax code rather than one with a litany of deductions, credits, and provisions for special interests.

In this testimony, I will focus on three key ideas that should be central in the upcoming debate: simplicity, neutrality, and trade-offs. While the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) moved in the right direction, the tax code remains a daunting morass of expiring, confusing, and duplicative provisions. Simplification can better deliver relief to taxpayers without breaking the bank or acting as a boon to the industry of tax advisors and planners. Neutrality should guide how we set the tax code up for growth to keep the US ahead of its competitors.

While second nature for this body, evaluating trade-offs takes on a new meaning with our current fiscal situation. Economic growth is essential to keep our debt load under control, and tax policy provides tools to achieve both growth and revenue. Economic analysis shows us that some options create stronger growth, more opportunity, and greater benefits for Americans than others. I will discuss some of those today, and my colleagues and I at the Tax Foundation would welcome the opportunity to provide further help as you consider various policy options in the coming months. While certain tax provisions have become ingrained in Americans’ way of thinking, my hope is that prioritizing simplicity and neutrality in the tax code will ultimately become commonly understood as most beneficial to Americans.

Simplification Makes Filing Easier for Millions of Americans

Without congressional action, your constituents will feel the negative impact of next year’s tax expirations immediately. Tax withholdingWithholding is the income an employer takes out of an employee’s paycheck and remits to the federal, state, and/or local government. It is calculated based on the amount of income earned, the taxpayer’s filing status, the number of allowances claimed, and any additional amount the employee requests. tables will adjust, take-home pay will shrink, and tax filing will get more complicated and more expensive for millions of Americans. As nearly all individual changes in the TCJA expire just 15 months from now, exploring what worked well can help guide further efforts to simplify the tax code.

The expansion of the standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. Taxpayers who take the standard deduction cannot also itemize their deductions; it serves as an alternative. and higher threshold for the alternative minimum tax (AMT) were the most powerful provisions that simplified tax filing for individuals.

The Tax Foundation, using IRS estimates, calculates that these changes to the AMT and the standard deduction would save taxpayers up to $10 billion annually in compliance costs.[1] However, other TCJA provisions, such as the Section 199A deduction, were predicted to increase compliance costs. There remains significant room for improvement.

Consolidating income tax bracketsA tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. ; further limiting deductions, credits, and exemptions; and lowering marginal rates are a good recipe for tax simplification. Tax Foundation analysis shows that further work toward simplification could eliminate all itemized deductions to cover the revenue reductions from lower rates and a larger standard deduction.[2]

A larger standard deduction, lower marginal rates, and expanded child tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. were partially paid for by eliminating personal exemptions and limiting itemized deductions. These changes led to nearly 90 percent of taxpayers claiming the standard deduction in 2018, whereas only around 70 percent claimed it in 2016.[3]

Limiting itemized deductions played a crucial role in tax reform, and I don’t need to tell the members of this committee how contentious they continue to be. It is important to place those limitations in context, so we can think about future avenues for simplification. For example, the $10,000 limit on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction and the limit on mortgage interest deductionThe mortgage interest deduction is an itemized deduction for interest paid on home mortgages. It reduces households’ taxable incomes and, consequently, their total taxes paid. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) reduced the amount of principal and limited the types of loans that qualify for the deduction. for home values above $750,000, along with other changes to itemized deductions, raised $668 billion in the TCJA.[4]

However, placing that change in the context of the increased AMT, a parallel individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. system, tells an interesting story. As you may know, if a taxpayer falls under the AMT, he or she is not allowed any SALT deduction.

In tax year 2015, 10.3 million taxpayers had to calculate AMT liability, and 5 million actually paid it.[5] In 2016, among taxpayers owing AMT, 89 percent earned under $500,000.[6] AMT filers disproportionately filed in California, New York, and New Jersey.[7] Now, only 5.7 million taxpayers calculate AMT, with only 220,000 owing AMT liability.[8] Instead of millions of taxpayers complying with two tax codes and receiving no SALT deduction, they now save hours filing and can deduct

Further work on the SALT deduction cap should be done as many state-level pass-through entity taxes act as workarounds to that cap. Tax Foundation modeling shows that a permanent SALT deduction cap would increase federal revenues by about $1.2 trillion from 2026 to 2033 and nearly $1.4 trillion if state-level workarounds are ended.[9]

The US Tax Code Remains Progressive

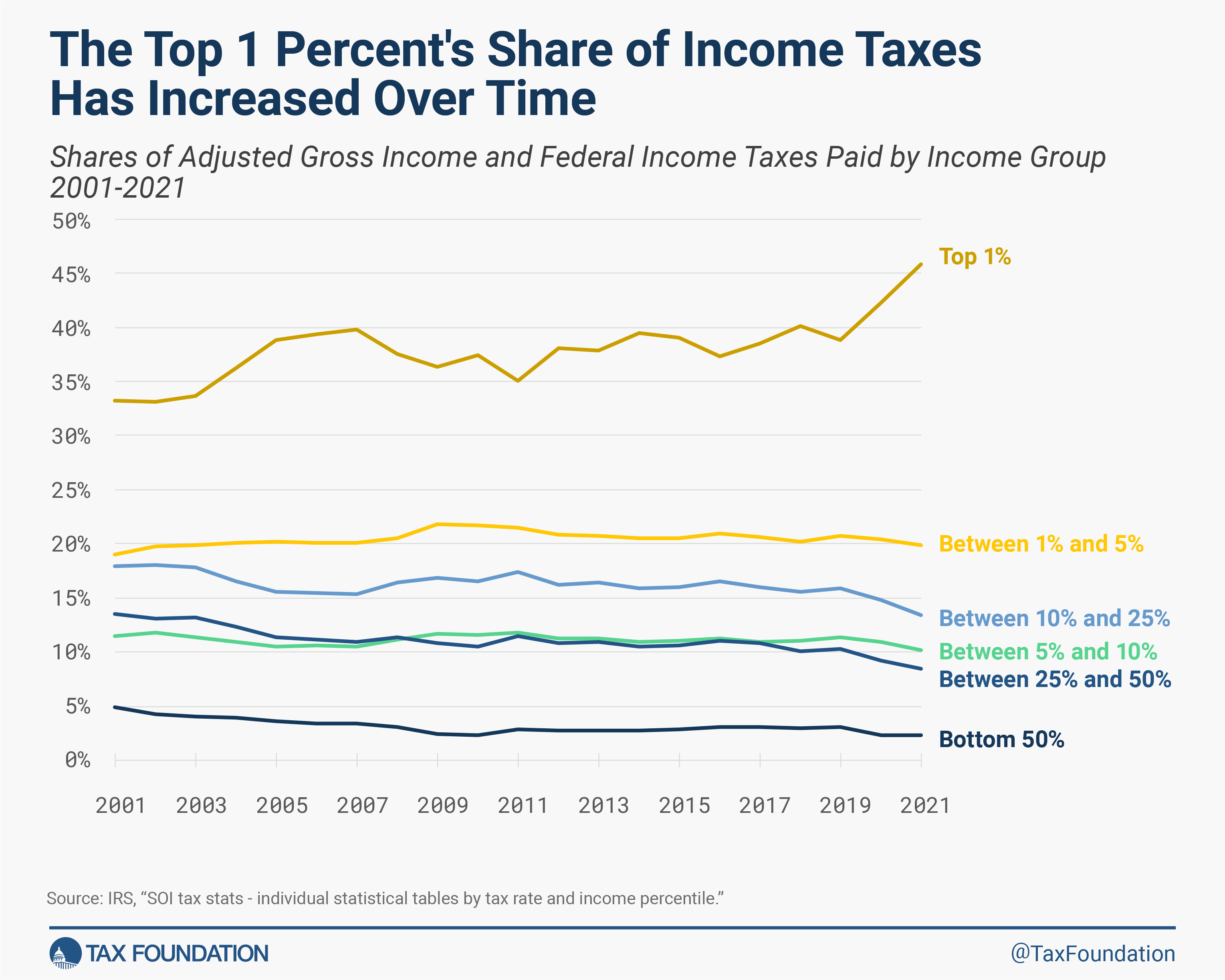

The US tax code has remained highly progressive, even after the TCJA In 2021, the top 1 percent of taxpayers paid 45.8 percent of all federal income taxes while they earned only 26.3 percent of all income. The bottom 50 percent of taxpayers paid 2.3 percent of all federal income taxes.[10]

An even wider lens view of the tax and transfer system in the US shows that the bottom quintile of households have an effective tax rate of negative 127 percent, while the highest quintile pays an effective tax rate of 30.7 percent.[11] To me, that seems like a sufficiently progressive taxA progressive tax is one where the average tax burden increases with income. High-income families pay a disproportionate share of the tax burden, while low- and middle-income taxpayers shoulder a relatively small tax burden. and transfer system.

The progressivity of the US tax code also raises questions about how much additional revenue can be squeezed from high-income earners if policymakers are unwilling to broaden the tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. and simplify the tax code in a way that increases neutrality and raises revenue.

Though some may think targeting upper-income earners is a fiscally responsible way to address the deficit while tackling inequalities, this is unlikely to succeed on its own.

Brian Riedl from the Manhattan Institute analyzed several policies that would increase taxes on high-income earners and wealthy individuals and measured them against our annual deficits. Even with aggressive hikes, policies focused only on high-income earners and the wealthy would close less than one-third of our annual budget deficits.[12]

This means that closing that budget gap would require significant spending reductions or broadening the lens for additional revenue raisers beyond those in higher earnings or wealth categories.

One policy the Chairman has focused some of his legislative efforts on, and that has been a part of presidential budgets in recent years, is a tax on unrealized capital gains. This approach would make the tax code decidedly more complex, raise the tax burden on saving and entrepreneurship, and introduce complicated new reporting and filing requirements.

Neutral Tax Policy Supports Business Investment

In 2023, Tax Foundation released its “Growth and Opportunity” tax plan. Over the 10-year budget window, the plan increases tax revenue, grows the economy, and takes dramatic steps toward a truly neutral tax code.[13]

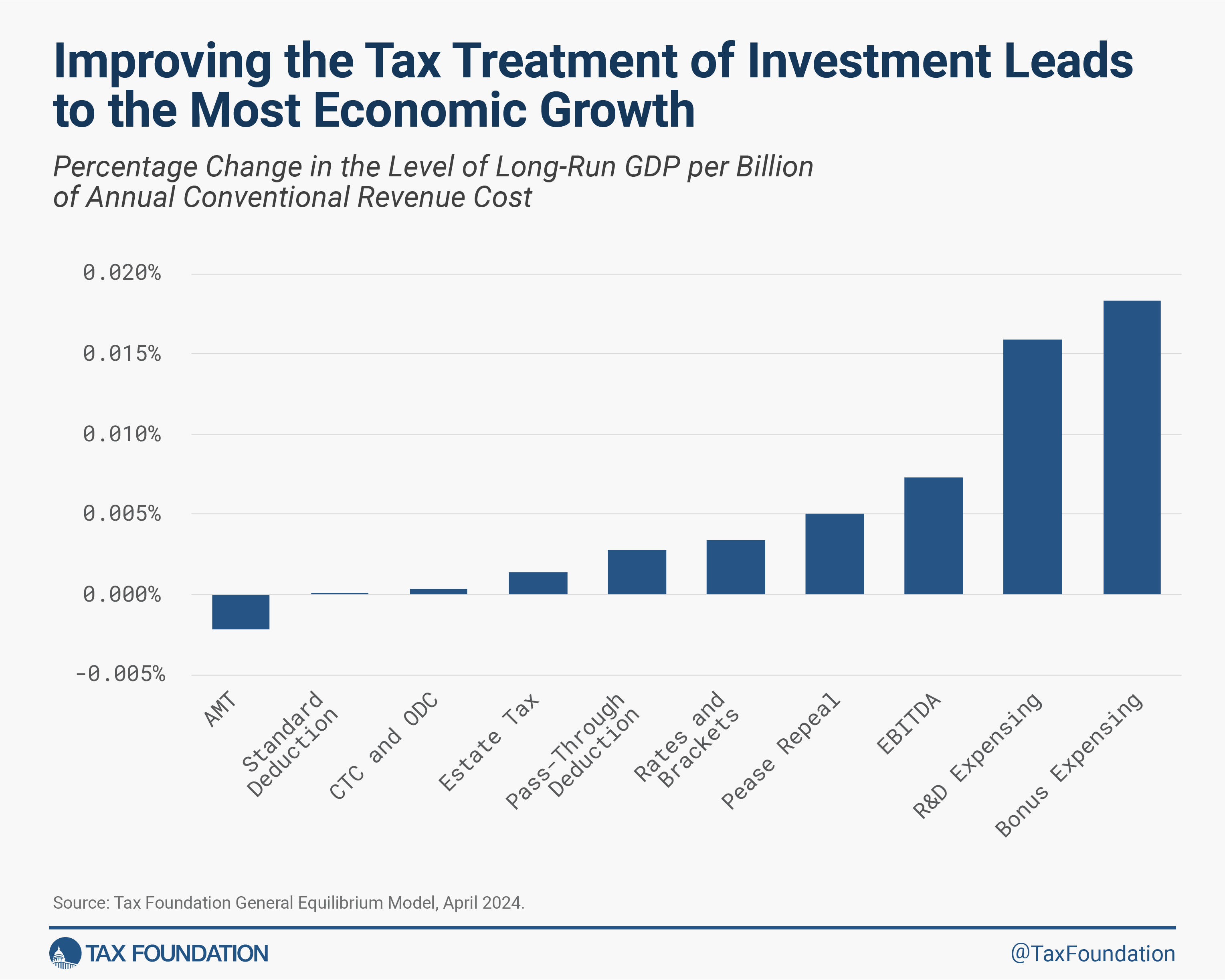

In the context of less fundamental reforms, the Tax Foundation has long focused on promoting the valuable policy of full and immediate expensing for business investments. Making 100 percent bonus depreciationBonus depreciation allows firms to deduct a larger portion of certain “short-lived” investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings in the first year. Allowing businesses to write off more investments partially alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. permanent and canceling amortization for research and development investments are the quickest ways to ensure the neutral treatment of investment. But we need to go far beyond those policies if we want to orient our tax code for economic growth.

Our tax code should treat all business investment neutrally. We believe that businesses have the know-how to decide when and where to invest without the tax code standing in the way. History cautions us against a code that micromanages business investment as it leads to a less dynamic economy.

A lower, 21 percent corporate tax rate supports business investment in the US and allows us to compete more effectively for new investments. Domestic companies are more likely to start projects or invest more than they otherwise would have. Critically, American workers and families benefit when businesses invest more: their wages increase and more jobs are created.

One hundred percent bonus depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. is the most pro-growth element of the TCJA, providing the most growth for its revenue cost.

The TCJA fell short of truly creating tax parity across all forms of business. The ultimate solution is integrating the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. so that all businesses are subject to a single layer of tax. Former Chairman Orrin Hatch made great strides in finding ways the US could implement such a system.[17] While the pass-through deduction attempts to achieve equal treatment, true parity is best accomplished through integration where all businesses are under a uniform tax treatment.[18]

While the InflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. Reduction Act improved neutrality in some ways (e.g., by consolidating energy production credits into a new, technologically neutral credit), it moved the tax code away from neutrality in many more ways. The new corporate alternative minimum tax and suite of green energy tax credits pick winners and losers. They are especially complicated provisions, requiring volumes of Treasury regulations and creating widespread uncertainty for taxpayers.

Perhaps the clearest picture is painted by the changing scores of the legislation from the Joint Committee on Tax (JCT) as regulations have been finalized. In August 2022, immediately after passage, JCT estimated the green energy tax credits would cost $271 billion over the next 10 years. In May 2023, less than a year later, JCT increased that estimate to $536 billion (and this “preliminary” score is still the most recent estimate JCT has provided).[19] New Treasury guidance explains much of the change, and guidance continues to roll out more than two years after the law was enacted. We at the Tax Foundation know that tax modeling is a tough job, but that job becomes nearly impossible when estimating the impacts of such novel and complicated provisions that grant so much authority to the Treasury Secretary for interpretation and implementation.

IRA Green Energy Credit Fiscal Costs as Estimated by the Joint Committee on Taxation, 2023 to 2031

| JCT Score (August 2022), 2023-2031 | Preliminary Revised JCT Score (May 2023), 2023-2031 | Net Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Credit for Electricity from Renewables (Section 45) | $51.10 | $63.60 | $12.50 |

| Modification of Energy Credit (Section 48) | $14 | $60.10 | $46.10 |

| Clean Vehicle Credits | $11.10 | $69.40 | $58.30 |

| Advanced Manufacturing Production Credit (Section 45X) | $30.60 | $132.50 | $101.90 |

| Carbon Sequestration Credit (Section 45Q) | $3.20 | $17.40 | $14.20 |

| Clean Fuel Production Credit (Section 45Z) | $2.90 | $7.40 | $4.50 |

| Clean Electricity Investment Credit (48E) | $50.90 | $71.70 | $20.80 |

| Other | $107.20 | $114.30 | $7.10 |

| Total | $271.00 | $536.40 | $265.40 |

Another non-neutral and complicated feature of the Inflation Reduction Act is the corporate alternative minimum tax (CAMT), designed to tax the financial statement income of US companies reporting more than $1 billion of income on average over the last three years. That may sound simple, but it has proven very difficult for the Treasury Department and the IRS to implement, as final regulations have still not been released, and cumbersome for taxpayers to comply with. In a recent survey of large companies targeted by the CAMT, most companies indicated they do not expect to pay additional tax under the CAMT rules, yet have incurred considerable expense complying with it, including by calculating CAMT liability and determining if they are in scope. Several companies pointed to the CAMT as a major reason their compliance costs have risen in recent years.[20]

While working to improve the neutrality of the tax code, policymakers should also examine how many tax-exempt entities compete directly with for-profit, taxable entities. My colleague, Scott Hodge, has written extensively on this issue. The tax code clearly takes sides when it allows for-profit, taxable entities to compete with non-profit, tax-exempt organizations that earn substantial amounts of business-like income.[21]

US Tax Code Must Balance Fiscal Responsibility with Economic Growth

When considering provisions for 2025, comparing their “bang for the buck” can help policymakers balance being fiscally responsible with promoting growth. The Tax Foundation has ranked commonly discussed provisions by their ability to produce growth per revenue lost. Highly ranked provisions can actually reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio over the long run when accounting for the impacts on economic growth.[22]

This bang-for-the-buck analysis provides a useful litmus test for policies when the main objective is growth. However, it does not capture other benefits, like simplification, that would result from eliminating the AMT and increasing the standard deduction.

Bang-for-the-buck analysis also helps illuminate where revenue reductions will be most helpful in boosting growth. The TCJA was clearly a pro-growth reform, supporting business investment and the repatriationRepatriation is the process by which multinational companies bring overseas earnings back to the home country. Prior to the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the US tax code created major disincentives for US companies to repatriate their earnings. Changes from the TCJA eliminate these disincentives. of foreign earnings, while many valuable assets also returned to the US tax base.

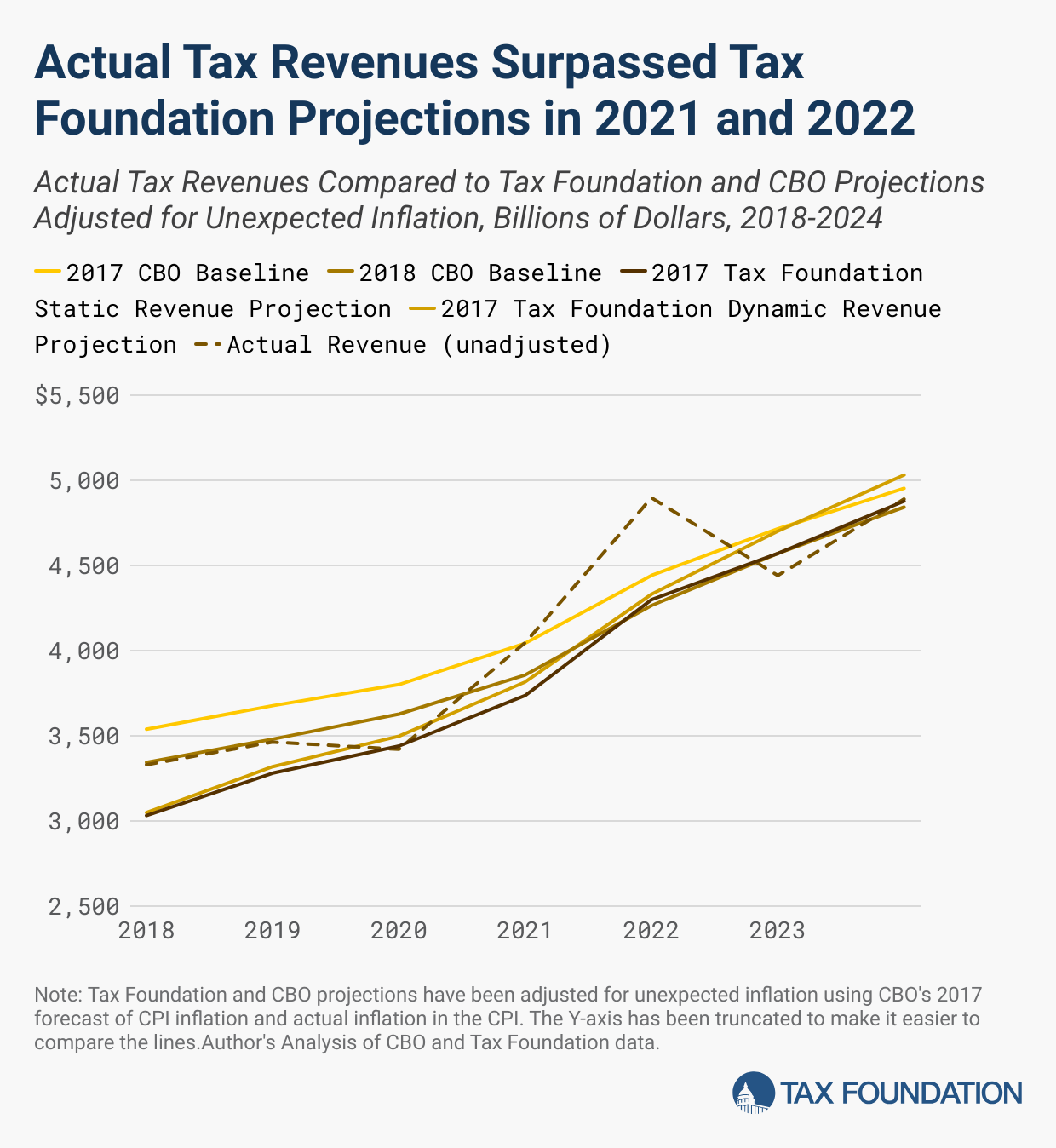

Even with these positive impacts, the TCJA has not paid for itself, though the tax system still raised historically average revenue after its passage. Looking at Congressional Budget Office (CBO) baseline estimates before and after the TCJA, we can reasonably say that revenues have remained within historical norms and surpassed the Tax Foundation’s own original estimates for revenue.[23]

However, the upcoming expirations have a much heftier price tag for a multitude of reasons, and simple extension will not produce significant economic growth compared to its cost.[24]

Since the TCJA, we have seen legislation pass Congress that is tremendously costly and moves the tax code away from simplicity and neutrality. As mentioned, the tax credits in the Inflation Reduction Act are a prime example. The most recent information we have, coming from Treasury’s tax expenditureTax expenditures are departures from a “normal” tax code that lower the tax burden of individuals or businesses through an exemption, deduction, credit, or preferential rate. However, defining which tax expenditures grant special benefits to certain groups of people or types of economic activity is not always straightforward. estimates and analysis by the CBO, indicates these credits will cost more than $1 trillion over the next decade.[25] Another example is the CHIPS Act, which contained $52 billion in manufacturing incentives in addition to $24 billion in investment tax credits. As the Committee evaluates opportunities to improve growth and revenue per dollar spent, it should consider altering the corporate alternative minimum tax and the green energy credits with an eye toward simplification and fiscal responsibility.

Conclusion

The TCJA moved the tax code toward simplicity and neutrality in many ways, and away from them in others. The coming months will be ripe with opportunity to simplify taxes for millions of taxpayers, orient the tax code for growth, and ensure a stable fiscal trajectory for the United States. Policymakers have the benefit of experience and data to approach these opportunities wisely, and the Tax Foundation will be standing by to help. Taking the right lessons from previous efforts for tax reform can help ensure that the next chapter of tax reform is better yet.

Thank you again for having me, and I look forward to your questions.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe[1] Erica York and Alex Muresianu, “The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Simplified the Tax Filing Process for Millions of Households,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 7, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-simplified-the-tax-filing-process-for-millions-of-americans/.

[2] Erica York, Alex Durante, Huaqun Li, Garrett Watson, and William McBride, “Options for Navigating the 2025 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Expirations,” Tax Foundation, May 7, 2024, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/2025-tax-reform-options-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act/.

[3] Alex Muresianu, “How Did the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Simplify the Tax Code,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 7, 2024, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/tcja-complexity-compliance/.

[4] The Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects Of the Conference Agreement for H.R. 1, The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Dec. 18, 2017, https://www.jct.gov/publications/2017/jcx-67-17/.

[5] Erica York and Alex Muresianu, “The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Simplified the Tax Filing Process for Millions of Households.”

[6] Alex Muresianu, “How Did the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Simplify the Tax Code.”

[7] Scott Eastman, “The Alternative Minimum Tax Still Burdens Taxpayers with Compliance Costs,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 4, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/alternative-minimum-tax-burden-compliance/.

[8] Scott Eastman, “The Alternative Minimum Tax Still Burdens Taxpayers with Compliance Costs.”

[9] Garrett Watson, “Policymakers Must Weigh the Revenue, Distributional, and Economic Trade-Offs of SALT Deduction Cap Design Options,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 7, 2023.

[10] Erica York, “Summary of the Latest Federal Income Tax Data, 2024 Update,” Tax Foundation, Mar. 13, 2024, https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/federal/latest-federal-income-tax-data-2024/.

[11] Timothy Vermeer, Alex Durante, Erica York, and Jared Walczak, “America’s Progressive Tax and Transfer System: Federal, State, and Local Tax and Transfer Distributions,” Tax Foundation, Mar. 30, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/who-pays-taxes-federal-state-local-tax-burden-transfers/.

[12] Brian Riedl, “The Limits of Taxing the Rich,” Manhattan Institute, Sep. 21, 2023, https://manhattan.institute/article/the-limits-of-taxing-the-rich.

[13] William McBride, Huaqun Li, Garrett Watson, Alex Durante, Erica York, and Alex Muresianu, “Details and Analysis of a Tax Reform Plan for Growth and Opportunity,” Tax Foundation, Jun. 29, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/growth-opportunity-us-tax-reform-plan/.

[14] Erica York, Huaqun Li, Daniel Bunn, Garrett Watson, and Cody Kallen, “The Economic, Revenue, and Distributional Effects of Permanent 100 Percent Bonus Depreciation,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 30, 2022, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/permanent-100-percent-bonus-depreciation-effects/.

[15] Gabriel Chodorow-Reich, Owen M. Zidar, and Eric Zwick, “Lessons from the Biggest Business Tax Cut in US History,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 326272, July 2024, https://www.nber.org/papers/w32672.

[16] E. Mark Curtis, Daniel G. Garrett, Eric C. Ohrn, Kevin A. Roberts, and Juan Carlos Suarez Serrato, “Capital Investment and Labor Demand,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 29485, November 2021, https://www.nber.org/papers/w29485.

[17] Senator Orrin Hatch, “Statement at Finance Hearing on Corporate Integration,” United States Committee on Finance, May 17, 2016, https://www.finance.senate.gov/chairmans-news/hatch-statement-at-finance-hearing-on-corporate-integration.

[18] Alex Durante, “Higher Taxes Under House Ways and Means Plan Emphasize Need for Corporate Integration,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 13, 2021, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/corporate-integration-tax-reform/.

[19] See Table 2 in William McBride, Alex Muresianu, Erica York, and Michael Hartt, “Inflation Reduction Act One Year After Enactment,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 16, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/inflation-reduction-act-taxes/.

[20] William McBride, “Results of a Survey Measuring Business Tax Compliance Costs,” Tax Foundation, Sep. 4, 2024, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/us-business-tax-compliance-costs-survey/.

[21] Scott Hodge, “Reining in America’s $3.3 Trillion Tax-Exempt Economy,” Tax Foundation, Jun. 18, 2024, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/501c3-nonprofit-organization-tax-exempt/.

[22] Erica York, Alex Durante, Huaqun Li, Garrett Watson, and William McBride, “Options for Navigating the 2025 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Expirations.”

[23] Daniel Bunn, “How Have Federal Revenues Evolved since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act?,” Tax Foundation, Jul. 10, 2024, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/2017-tax-law-revenue/.

[24] Erica York, Garrett Watson, Alex Durante, Huaqun Li, Peter Van Ness, and William McBride, “Details and Analysis of Making the 2017 Tax Reforms Permanent,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 8, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/making-2017-tax-reform-permanent/.

[25] Alex Muresianu, “When Looking to Reform Inflation Reduction Act, Start with EV Credits,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 11, 2024, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/ev-tax-credits-inflation-reduction-act/.