Nicole Kaeding, Vice President of Federal and Special Projects at the Tax Foundation, testifies before the House Ways and Means Select Revenue Measures Subcomittee on the impact of limiting the SALT deduction. See her full testimony below.

The Impacts of Limiting the State and Local Taxes Paid Deduction

Chairman Thompson, Ranking Member Smith, and members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to speak to you today regarding the recent changes to the state and local taxes paid deduction and its impact on communities.

The TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. Foundation is the nation’s oldest organization dedicated to promoting economically sound tax policy at the federal, state, local, and global levels of government. We are a nonpartisan 501(c)(3) organization.

For more than 80 years, the Tax Foundation’s research has been guided by the principles of sound tax policy. Taxes should be neutral to economic decision-making, and they should be simple, transparent, and stable.

Today, I have been asked to discuss the recent changes made to the state and local taxes (SALT) paid deduction within Public Law 115-97, known informally as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA).

The SALT Deduction Prior to Reform

Since the creation of the federal income tax in 1913, the federal government has allowed individuals to deduct taxes paid to state and local governments.[1] Prior to the TCJA, taxpayers could deduct their income or sales tax liabilities, plus their property taxes paid. For most taxpayers, they deducted their income and property taxes. Residents of no-income-tax states would instead deduct their sales taxes paid.

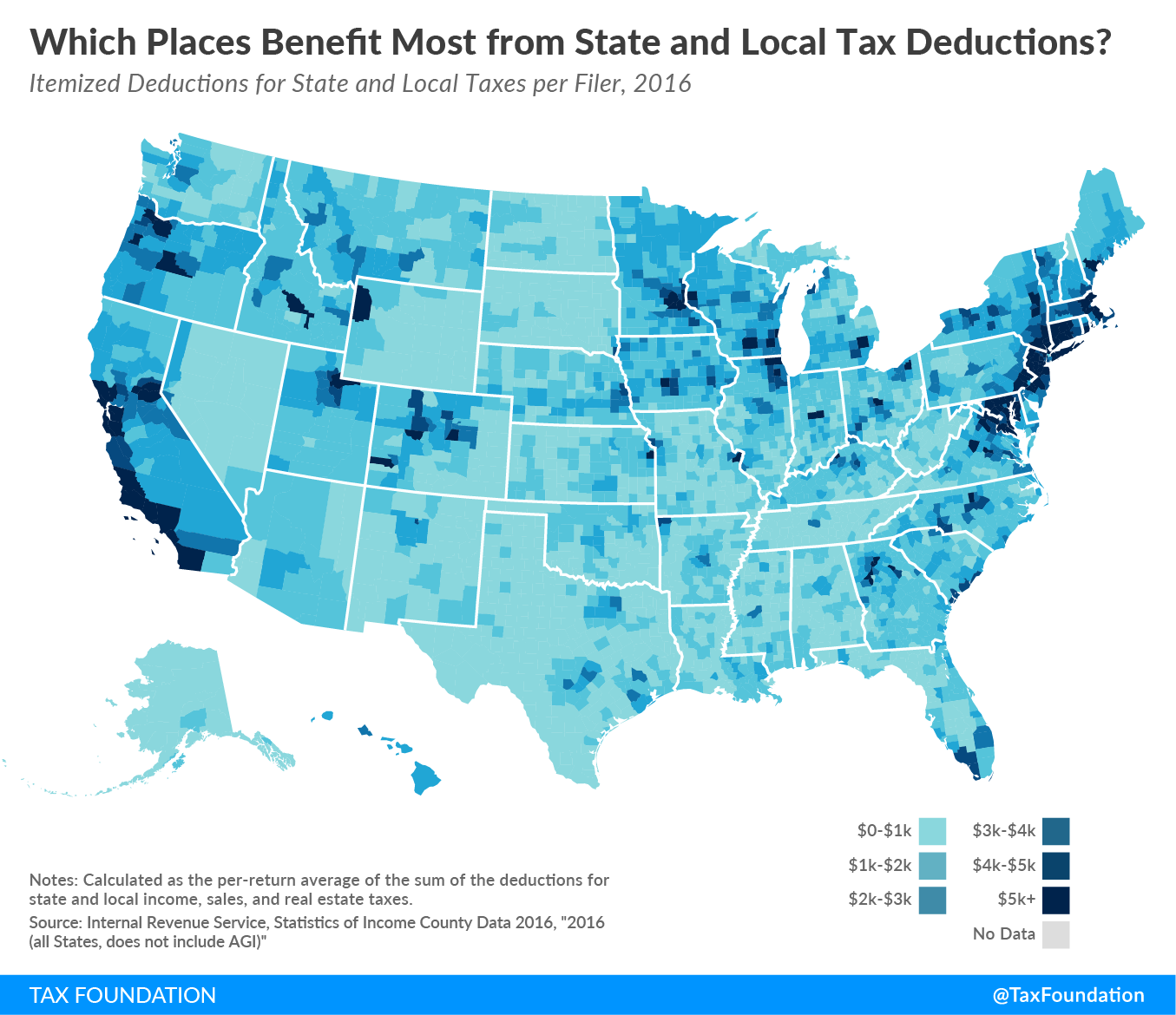

The map below shows the mean deduction amount taken per return by county prior to the TCJA.

Figure 1.

Prior to the TCJA, the top ten counties that claimed the SALT deduction were concentrated in four states: New Jersey, California, New York, and Connecticut.[2] Six states– California, New York, New Jersey, Illinois, Texas, and Pennsylvania– claimed more than half of the deduction.[3]

The SALT deduction is often discussed as benefiting taxpayers in high-tax states, but that analysis obscures the true impact of the SALT deduction. While it does benefit those taxpayers, it is better understood as benefiting high-income taxpayers in high-tax jurisdictions. For example, the deduction is used often by residents of New York state, but as the map illustrates, its usage is not monolithic. In 2016, the mean deduction taken in Westchester County, New York was almost $16,000. But the mean deduction taken in St. Lawrence County, New York was less than $2,000. The deduction is worth more in Westchester County for several reasons: namely, that incomes and housing values are higher. The median home price in Westchester County is $513,300, compared to $88,000 in St. Lawrence County.[4] Property taxes are calculated based on housing prices, resulting in a large variance in taxes paid even within New York. The median property taxes paid in Westchester County was more than $10,000, while it was $2,208 in St. Lawrence County.[5]

Even in low-tax states, such as Indiana, usage of the deduction varies. The mean deduction in Hamilton County, a high-income suburb of Indianapolis, is approximately $5,500, compared to approximately $1,000 in Washington County in Southern Indiana.

It is too simple to say that the deduction only benefits high-tax states. It is better understood as benefiting high-income individuals, many of whom reside in high-tax jurisdictions with high housing values. Prior to the TCJA, high-tax states and localities were able to raise taxes without their taxpayers feeling the entire impact of the high tax levels. When a state or local tax was raised by $1, individuals who itemized their federal deductions would only experience a net tax increase of $0.60 to $0.90, depending on their federal marginal income tax rate. Jurisdictions with higher-income residents received more of a benefit than those with lower-income residents. The value of the deduction increased with income. In some ways, it allowed high-tax states and localities to export their tax liabilities to taxpayers in other states, particularly low-tax, low-income states.

Generally, policymakers and their constituents argue for a progressive set of tax and spending policies at the federal and state levels. Higher-income individuals should be subject to higher levels of taxation to finance spending programs that benefit low- and middle-income individuals. The SALT deduction, however, distorts this preference. The SALT deduction provides a larger benefit to states with high levels of income and well-being, compared to other states.

Prior Limitations to the SALT Deduction

Federal policymakers have enacted multiple limits to the SALT deduction since its creation. Some limitations have been explicit, such as elimination of the deduction for state sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. paid in 1986.[6] (That deduction was partially restored later.) Others have been hidden, such as through the alternative minimum tax and the Pease limitation.

The alternative minimum tax (AMT) was passed in 1969, to limit the ability of high-income taxpayers to escape federal taxation from the overuse of tax expenditures.[7] The AMT changed somewhat over time, but the essence of the minimum tax has stayed constant; taxpayers must calculate their tax liabilities under the alternative tax base, in addition to the traditional tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. , and pay whichever tax liability is higher.

Prior to the TCJA, the AMT had several components, but the most notable for this context was that the SALT deduction was disallowed.[8] Taxpayers hit by the AMT were limited in their ability to deduct their state and local taxes paid.

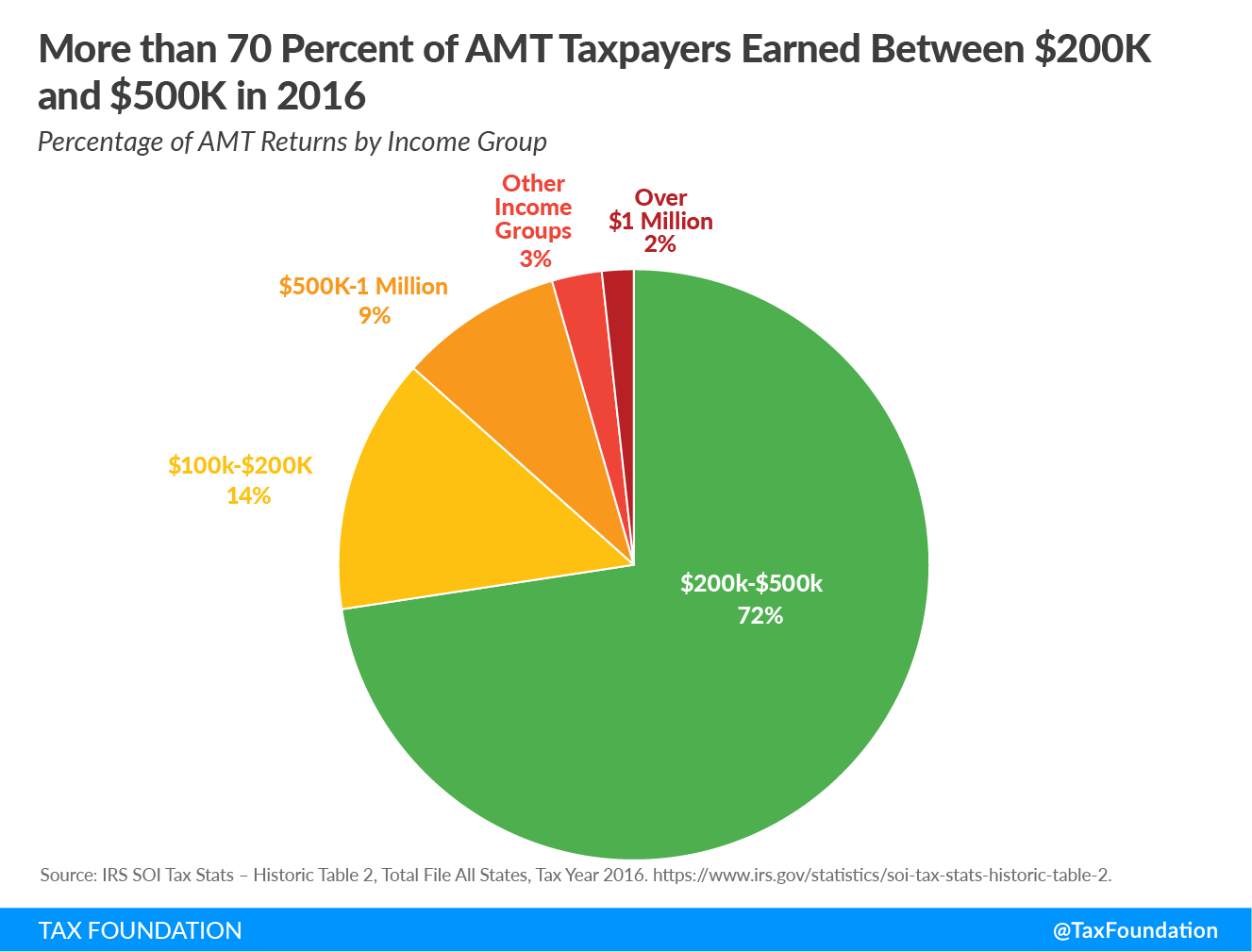

Prior to the TCJA, the AMT hit taxpayers making between $200,000 and $500,000 hardest. In 2015, almost 60 percent of taxpayers in that income range were subject to the AMT.[9] This means that those filers did not receive the full benefit of their SALT deduction. In 2016, more than 70 percent of AMT taxpayers earned income between $200,000 and $500,000.

Figure 2.

Additionally, the Pease limitation impacted the ability of high-income taxpayers to receive the full benefit of the SALT deduction. Named for late Congressman Donald Pease (D-OH), the Pease limitation reduced the value of itemized deductions for high-income taxpayers by phasing out deductions by 3 percent for every dollar of taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. Taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. above a threshold.[10] In 2017, that threshold was $261,500 for single filers and $313,800 for married couples.[11] Up to 80 percent of a filer’s itemized deductions could be capped by the Pease limitation. Taxpayers with incomes above those levels would also have the value of their SALT deduction impacted, as the value would phase out by increasing their taxable income.

These two provisions, the AMT and the Pease limitation, meant that many taxpayers were unable to deduct the full value of their state and local taxes paid, even though the deduction was not explicitly limited.[12]

The SALT Deduction Post-Reform

The TCJA limited the SALT deduction available to individual taxpayers. Starting with the 2018 tax year, the deduction was limited to $10,000 for state and local income taxes paid. The limit, however, is scheduled to expire on December 31, 2025, when most of the individual tax changes in the TCJA are set to expire. The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimated that the limit would raise $668 billion from 2018 to 2027.[13]

The $10,000 limit is not adjusted for inflation, meaning that it will impact more taxpayers over time. In addition, the value does not reflect marital status. Single and married taxpayers are limited to the same $10,000 deduction.

The SALT deduction limit was part of a larger change to the individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. . The TCJA lowered tax rates and expanded the standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. Taxpayers who take the standard deduction cannot also itemize their deductions; it serves as an alternative. to $12,000 for single filers and $24,000 for married couples, a functional doubling of the deduction. It repealed personal exemptions and doubled the child tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. from $1,000 to $2,000. At the same time, the eligibility of the child tax credit was expanded. Previously, the credit began phasing out at $110,000 in income for married couples. Now, it is $400,000 in income. The TCJA also limited the impact of the alternative minimum tax and limited the mortgage interest deduction, among other changes.

These changes, in total, lowered taxes for most Americans. The Tax Policy Center estimated that 65 percent of taxpayers would pay less in taxes in 2018 than they would have under previous law. Only 6.3 percent would have a higher tax liability.[14]

Limiting the SALT deduction helped finance broader tax reforms, for both individuals and businesses, within the TCJA. While the TCJA is not perfect, it is projected to be a pro-growth tax reform. According to the Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth model, GDP is estimated to be 1.7 percent higher in the long run because of the TCJA. It is projected to create 340,000 jobs and raise long-run wages by 1.5 percent.[15]

While the new SALT cap increases federal taxable income for high-income taxpayers, these taxpayers benefited from other tax changes. The new lower tax rates, expanded child tax credit, and limiting of the AMT, among others, all benefited taxpayers now impacted by the SALT cap. On net, even many taxpayers limited by the new SALT deduction had their taxes lowered in 2018.

The Distributional Impacts of Capping the SALT Deduction

Before the TCJA, 91 percent of the benefit of the state and local taxes paid deduction was claimed by those with income above $100,000.[16] Limiting the deduction, therefore, is progressive. Its impact is mostly limited to high-income households.

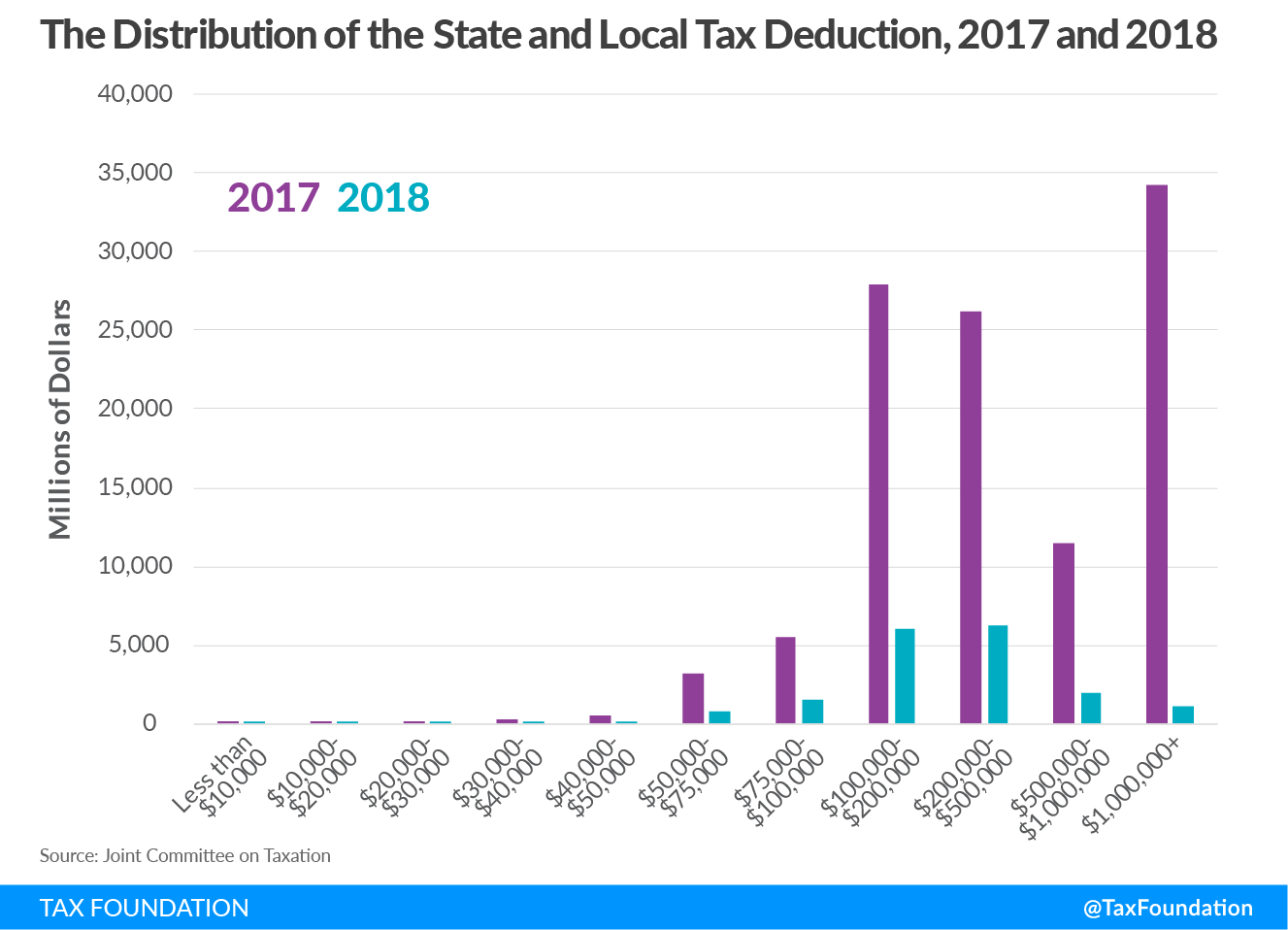

The chart below shows the distributional impact of limiting the deduction.

Figure 3.

For individuals with income between $100,000 and $200,000, JCT estimates that the dollar benefit of the SALT deduction falls from $28 billion in 2017 to $7 billion in 2018. For those with income between $200,000 and $500,000, it falls from $26 billion to $7.1 billion. For those with income between $500,000 and $1,000,000, the benefit of the deduction falls from $11.5 billion to $2.2 billion. It falls from $34 billion to 1.3 billion for those with income above $1,000,000.

Contrary to popular arguments, the SALT cap does not disproportionately impact middle-income taxpayers. The benefits concentrate above $100,000 in income, which some have labeled as “middle-income.” However, these individuals are in approximately the top 20 percent of taxpayers, outside the traditional definition of middle-income. In 2016, the top 25 percent of taxpayers had incomes above $81,000. The top 10 percent of taxpayers had incomes above $140,000. The top 5 percent of taxpayers had income above $200,000.[17] Very few middle-income taxpayers claimed the deduction before the TCJA, meaning they are not impacted by the new cap.

Some have also argued that this cap is devasting to taxpayers of specific states. While taxpayers with high income in high-tax states bear a higher cost of the limiting of the SALT deduction, it is also true that taxpayers in these states still often received net tax cuts. For example, 6.3 percent of Americans were estimated to pay more in 2018 due to the TCJA. In New Jersey, that increases to 10.2 percent, the highest of any state. However, 62 percent of New Jersey residents were estimated to have a tax cut, with the average tax cut being $2,740. In New York, 8.3 percent of tax filers were estimated to pay more in 2018, with 7.7 percent of payers in Virginia paying more. Still, 61 percent of New York taxpayers and 70 percent of Virginia taxpayers are estimated to have paid less in 2018 than under prior law.[18]

However, taxpayers that experienced tax increases in 2018 were impacted by more than just the SALT deduction cap. Many taxpayers impacted by the new SALT cap still had net tax cuts due to the other tax changes. For example, taxpayers could be limited by the new SALT deduction cap, but also benefit from the new expanded child tax credit, resulting in a net tax cut.

Additionally, some taxpayers might stop taking the capped SALT deduction due to the newly expanded standard deduction. While their SALT deduction is limited, they are now better off taking the larger standard deduction.

At the same time, taxpayers limited by the SALT cap but do not have children, or have dependents that do not qualify for the child tax credit, could have a small tax increase. But it isn’t just the SALT cap that raises their net tax liability; instead, it is an interaction with the repeal of personal exemptions, too.

But regardless of the interactions, the tax increases caused in some part by the SALT deduction would be progressive, impacting high-income taxpayers.

The Impact of Repealing or Limiting the SALT Cap

Since the passage of the TCJA, policymakers have debated repealing or limiting the new SALT cap. Repealing the deduction limit would be a regressive taxTaxes can create different burdens on taxpayers of different income levels, measured by comparing taxes paid as a fraction of income. A regressive tax is one that creates a larger burden on lower-income taxpayers than on middle- or higher-income taxpayers. policy change; the benefits would skew to those with higher incomes. The benefits of repeal overwhelmingly benefit those in the top 20 percent of taxpayers. Even in 2025, when the impacts of the non-inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. adjusted cap are most felt, the benefits disproportionately skew to high-income households.[19]

| Income Group | Percent Change in After-tax Income |

|---|---|

|

Source: Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model, October 2018 |

|

| 0% to 20% | 0.00% |

| 20% to 40% | 0.00% |

| 40% to 60% | 0.01% |

| 60% to 80% | 0.04% |

| 80% to 90% | 0.18% |

| 90% to 95% | 0.47% |

| 95% to 99% | 1.25% |

| 99% to 100% | 2.79% |

| Total | 0.67% |

The distributional impact is the result of several different phenomena. First, deductions are worth more to high-income filers; deductions against a 37 percent rate are more valuable than deductions against a 22 percent rate. Second, because the TCJA doubled the standard deduction, fewer taxpayers are itemizing. Only 10 percent of taxpayers are now itemizing, compared to 30 percent under previous law. The JCT estimates that of those that itemize, 67 percent have income above $100,000.[20]

Additionally, repealing the SALT cap would significantly reduce federal revenues by $673 billion from 2019 to 2028[21]. Some policymakers have suggested offsets to repealing the cap, such as raising the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate or raising the top individual income tax rate to 39.6 percent. However, these policies are flawed.

Repealing the SALT cap financed by raising the corporate income tax rate would raise taxes on the bottom 90 percent of taxpayers, while cutting it for the top 10 percent of taxpayers. This trade would also reduce long-run GDP by 0.19 percent.[22]

Repealing the SALT cap financed by raising the top marginal income tax rate would not raise taxes on low- and middle-income taxpayers, unlike the previous proposal, but it would fall short of offsetting any revenue loss. Federal revenues would be reduced by $532 billion over the next 10 years, with tax cuts concentrated on the top 20 percent of taxpayers, an expensive and regressive tax cut.[23]

A final proposal would raise the SALT cap from $10,000 to $15,000 for single filers and $30,000 for married couples.[24] Those caps would also be adjusted for inflation annually. This policy would reduce federal revenues by a lesser amount than a straight repeal of the cap. Revenues would be reduced by $223 billion between 2020 and 2029. However, similar distributional concerns are raised. It would make the tax code less progressive.

Taxpayers in the bottom three quintiles would not benefit from the change, with a small impact on those in the fourth quintile. Taxpayers in the top 20 percent, particularly those in the top 5 and 1 percent, would benefit the most.

| Income Group | Percent Change in After-tax Income |

|---|---|

|

Source: Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model, March 2019 |

|

| 0% to 20% | 0.00% |

| 20% to 40% | 0.00% |

| 40% to 60% | 0.00% |

| 60% to 80% | 0.03% |

| 80% to 90% | 0.16% |

| 90% to 95% | 0.41% |

| 95% to 99% | 0.82% |

| 99% to 100% | 0.42% |

| TOTAL | 0.25% |

The Impacts of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act on State Budgets

States use the federal tax code as the basis of their state tax codes. State codes refer directly to the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) in many places. This process is known as conformity.[25] For individuals, states often conform to the federal definition of adjusted gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total of all income received from any source before taxes or deductions. It includes wages, salaries, tips, interest, dividends, capital gains, rental income, alimony, pensions, and other forms of income. For businesses, gross income (or gross profit) is the sum of total receipts or sales minus the cost of goods sold (COGS)—the direct costs of producing goods, including inventory and certain labor costs. , while also conforming to many deductions and credits. In 2017, 27 states conformed to federal adjusted gross income.[26] State corporate income tax codes often conform to the federal definitions of taxable income. Prior to the TCJA, 41 states, for example, conformed to the federal definition of taxable income for corporations, either before or after net operating losses.

This makes the tax filing process easier for the taxpayer, as amounts and calculations from their federal return can be carried over to their state return. At the same time, it makes the tax code easier to administer for the state. They can rely upon federal tax statutes for definitions, IRC guidance for direction, and use federal tax audits as the basis of their audits.[27]

Therefore, when large changes are made to the federal tax code, such as those made by the TCJA, state tax codes are also impacted. At the federal level, the TCJA limited tax deductions, broadening the tax base. It then used that revenue to lower tax rates for individuals and corporations.

State tax bases, through conformity, became broader too; tax deductions at the state level were limited. However, states do not conform to federal tax rates.[28] While the federal government used the newfound revenue from base broadening to finance lower tax rates, state tax rates did not change. As a result, many states saw an increase in revenue from federal tax reform.

The increases in revenue were significant for many states.[29] For example, Georgia’s revenue over five years was expected to increase $5.2 billion. New York estimated an increase of $1.1 billion in fiscal year 2019. Virginia estimated an increase of $4.5 billion from fiscal years 2019 to 2024.[30]

Not all states have published revenue estimates from conformity, but of those that have, the overwhelming majority have forecasted revenue increases. Of the several states that have forecasted losses, those losses are largely due to the new 20 percent deduction for pass-through businesses in IRC §199A.[31] Six states initially conformed to §199A, but several, such as Oregon, have moved to decouple to limit the revenue loss.[32]

States have used this newfound revenue to finance tax changes.[33] States, such as Virginia[34] and Iowa, have lowered taxes for residents, because of the new revenue from conformity. Virginia, for example, will cut taxes by $1 billion, first by providing a tax credit for the 2018 tax year and then by expanding the state standard deduction, beginning for tax year 2019.

Notably, however, limiting the SALT deduction has had limited impacts on state tax codes, via conformity. States did not provide deductions for state taxes paid. State tax base broadeningBase broadening is the expansion of the amount of economic activity subject to tax, usually by eliminating exemptions, exclusions, deductions, credits, and other preferences. Narrow tax bases are non-neutral, favoring one product or industry over another, and can undermine revenue stability. , via conformity, came from other changes.

Other Impacts of Limiting the SALT Deduction

Tax Increases Under a SALT Cap

Some state policymakers have argued that the SALT cap has limited their ability to raise taxes. Prior to the TCJA, a $1 state tax increase only increased a taxpayer’s liability by between $0.60 to $0.90, depending on the individual’s federal marginal rate. The increase at the state level would increase their federal tax deductions. This acted like an implicit subsidy to state and local tax increases.

Now, with the cap, state tax increases are more acutely felt, as the federal deduction is limited. All else being equal, state and local policymakers might be limited in their ability to pass tax increases as individuals would be more impacted. However, it is not clear how binding this constraint will be in practice.

State and local governments have explored, and in some cases passed, tax increases on high-income individuals since the TCJA. New Jersey created a new tax bracket at $5 million in income in 2018. New York kept its millionaires’ tax. Illinois and Massachusetts are considering creating new millionaires’ taxes. In 2018, 22 cities in Minnesota held referendums to raise property taxes. Voters in 16 jurisdictions approved the measures.[35]

Additionally, if the goal is to subsidize state and local programs, policymakers should consider how to do it explicitly.

Housing Value Changes Under the SALT Cap

The TCJA limited the mortgage interest deductionThe mortgage interest deduction is an itemized deduction for interest paid on home mortgages. It reduces households’ taxable incomes and, consequently, their total taxes paid. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) reduced the amount of principal and limited the types of loans that qualify for the deduction. on high-value properties. Starting with purchases after the TCJA was passed, taxpayers can now only deduct interest on the first $750,000 in principal, compared to $1,000,000 under prior law. Limiting the mortgage interest deduction raises the cost of purchasing a high-value home, as the cost is no longer subsidized above the $750,000 principal value.

Additionally, property taxes on the high-value homes would likely no longer be deductible, as the taxpayer would have more than $10,000 in state and local taxes.

This combination of limiting the mortgage interest deduction and the SALT deduction is likely to have an impact on housing values. But there are several important considerations. First, these limits are progressive. Only high-income individuals can afford to purchase homes with more than $750,000 in principal. A $750,000 principal limit implies a $937,500 home price, assuming a 20 percent down payment. Borrowers should be affluent to afford such a mortgage balance, as principal and interest alone is $3,800 per month.[36]

Second, its impact would be limited to expensive areas of the country. There are very few areas of the country where the median home price reaches these levels. According to the National Association of Realtors, less than 0.5 percent of counties in the United States have median home prices exceeding $750,000.[37] In jurisdictions with median values below $750,000, the impact would be even less.

Third, any impact on housing values would be beneficial to many, particularly first-time homebuyers. By lowering the cost of purchasing a home, first-time buyers, all else being equal, would be more likely to afford a home. Current homeowners would experience a small decrease, but often individuals selling a home are also buying a new property. While they would not net as much on the sale, their next home would be less expensive too, holding the impact on their wealth constant.

Conclusion

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, passed in 2017, overhauled the federal tax code. It lowered tax rates, expanded the standard deduction and child tax credit, and limited the AMT and several notable deductions, including the SALT deduction. On net, most Americans had a tax cut.

Limiting the SALT deduction was a step to finance broad tax reform and help maintain progressivity within the tax code. Prior to tax reform, more than 90 percent of the benefits of the SALT deduction accrued to those with income above $100,000. The impacts of limiting the deduction are, therefore, concentrated among high-income individuals.

Even those impacted by the SALT cap often saw a net tax decrease. First, they often were previously impacted by prior implicit SALT limitations, such as the AMT and the Pease limitation, which were repealed by the TCJA. Second, some quit itemizing their deductions, switching to the expanded standard deduction. Filers also benefit from lower rates and the expanded child tax credit, among other changes.

To the small group of individuals with net tax increases, an estimated 6.5 percent in 2018, it is unlikely that the tax increase is solely due to the SALT cap. It is often due to interactions with other provisions, such as the repeal of personal exemptions.

The deduction cap is frequently cited as impacting state budgets; however, its impact is overstated. States saw an increase in revenue from tax reform, due to their conformity to the federal tax code. State and local governments have also explored and passed tax increases since the passage of the new SALT cap.

Tax reform is a difficult task. Limiting deductions and tax expenditures burdens those who benefit from their existence. But in the context of the TCJA, limiting the SALT deduction was a desirable and strong policy choice.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe[1] Jared Walczak, “The State and Local Tax DeductionA tax deduction allows taxpayers to subtract certain deductible expenses and other items to reduce how much of their income is taxed, which reduces how much tax they owe. For individuals, some deductions are available to all taxpayers, while others are reserved only for taxpayers who itemize. For businesses, most business expenses are fully and immediately deductible in the year they occur, but others, particularly for capital investment and research and development (R&D), must be deducted over time. : A Primer,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 545, Mar. 15, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/state-and-local-tax-deduction-primer/.

[2] Robert Bellafiore, “The Benefits of the State and Local Tax Deduction by County,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 5, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/state-and-local-tax-deduction-by-county-2016/.

[3] Walczak, “The State and Local Tax Deduction: A Primer.”

[4] U.S. Census, “Median Value (Dollars), Owner-Occupied Housing Units,” American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates 2013-2017.

[5] U.S. Census Bureau, “Mortgage Status by Median Real Estate Taxes Paid (Dollars), Owner-Occupied Housing Units,” American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates 2013-2017.

[6] Walczak, “The State and Local Tax Deduction: A Primer.”

[7] Scott Eastman, “The Alternative Minimum Tax Still Burdens Taxpayers with Compliance Costs,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 647, Apr. 4, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/alternative-minimum-tax-burden-compliance.

[8] Walczak, “How the State and Local Tax Deduction Interacts with the AMT and Pease Limitation,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 6, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/state-and-local-tax-deduction-amt-pease/.

[9] Erica York, “Under Conference Agreement, Fewer Households Would Face the Alternative Minimum Tax,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 16, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/conference-report-alternative-minimum-tax/.

[10] Kyle Pomerleau, “The Pease Limitation on Itemized Deductions is Really a SurtaxA surtax is an additional tax levied on top of an already existing business or individual tax and can have a flat or progressive rate structure. Surtaxes are typically enacted to fund a specific program or initiative, whereas revenue from broader-based taxes, like the individual income tax, typically cover a multitude of programs and services. ,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 16, 2014, https://taxfoundation.org/pease-limitation-itemized-deductions-really-surtax/.

[11] Kyle Pomerleau, “2017 Tax BracketsA tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. ,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 534, Nov. 10, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/2017-tax-brackets/.

[12] Other policy provisions within the last ten years have explored other implicit limits to the SALT deduction. For example, President Barack Obama (D) proposed limiting the value of all itemized deductions to 28 percent, meaning that high-income individuals would not get the full value of their itemized deductions in high-tax brackets.

[13] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Conference Agreement for H.R. 1, The “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” JCX-67-17, Dec. 18, 2017, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5053.

[14] Frank Sammartino, Philip Stallworth, and David Weiner, “The Effect of the TCJA Individual Income Tax Provisions Across Income Groups and Across the States,” Tax Policy Center, Mar. 28, 2018, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/effect-tcja-individual-income-tax-provisions-across-income-groups-and-across-states/full. These numbers change slightly if you include the impact of the corporate tax changes in the individual distributional tables, following JCT’s general practice. Then, 80 percent of taxpayers saw a net tax cut, while only 5 percent having a tax increase in 2018.

[15] Tax Foundation, “Preliminary Details and Analysis of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Dec. 18, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/final-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-details-analysis/.

[16] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Tables Related to the Federal Tax System as in Effect 2017 Through 2026,” JCX-32-18, Apr. 23, 2018, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?id=5091&func=startdown.

[17] Robert Bellafiore, “Summary of the Latest Federal Income Tax Data, 2018 Update,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 622, Nov. 13, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/summary-latest-federal-income-tax-data-2018-update/.

[18] Sammartino, Stallworth, and Weiner, “The Effect of the TCJA Individual Income Tax Provisions Across Income Groups and Across the States.”

[19] Kyle Pomerleau, “Eliminating the SALT Deduction Cap Would Reduce Federal Revenue and Make the Tax Code Less Progressive,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 4, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/salt-deduction-analysis/

[20] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Tables Related to the Federal Tax System as in Effect 2017 Through 2026.”

[21] Pomerleau, “Eliminating the SALT Deduction Cap Would Reduce Federal Revenues and Make the Tax Code Less Progressive.”

[22] Kyle Pomerleau, “The Impact of a Higher Corporate Tax Rate to Fund Eliminating the SALT Deduction Cap,” Tax Foundation, Sept. 13, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/higher-corporate-tax-rate-fund-eliminating-salt-deduction-cap/.

[23] Kyle Pomerleau and Huaqun Li, “Analysis of the SALT Act,” Tax Foundation, Mar. 11, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/salt-act/.

[24] Kyle Pomerleau, “Analysis of H.R. 1757: A Proposal to Raise the SALT Deduction Cap,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 29, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/raise-salt-deduction-cap-hr-1757-analysis/.

[25] Jared Walczak, “Tax Reform Moves to the States: State Revenue Implications and Reform Opportunities Following Federal Tax Reform,” Tax Foundation Special Report, No. 242, Jan. 31, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/state-conformity-federal-tax-reform/.

[26] Nicole Kaeding and Kyle Pomerleau, “Federal Tax Reform: The Impact on States,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 543, Mar. 8, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/federal-tax-reform-the-impact-on-states/.

[27] Kaeding and Pomerleau, “Federal Tax Reform: The Impact on States.”

[28] Ibid.

[29] A selected list of state conformity revenue estimates is available on the Tax Foundation’s website. https://taxfoundation.org/state-tax-conformity-revenue-effects/.

[30] Chainbridge Software, LLC, “Estimated Impact of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act on Virginia,” Jul. 27, 2018, https://www.finance.virginia.gov/media/governorvirginiagov/secretary-of-finance/pdf/master-revenue-reports/additional-reports/Chainbridge-Technical-Appendix-corrected-82318.pdf.

[31] Walczak, “Tax Reform Moves to the States: State Revenue Implications and Reform Opportunities Following Federal Tax Reform.”

[32] Walczak, “Toward a State of Conformity: State Tax Codes a Year After Federal Tax Reform,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 631, Jan. 28, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/state-conformity-one-year-after-tcja/.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Julia Varnier, “Governor Northam Signs Tax Conformity Legislation,” WTKR, Feb. 16, 2019, https://wtkr.com/2019/02/16/governor-northam-signs-tax-conformity-legislation/.

[35] Gregg Aamot, “For Minnesota Cities and Counties, the 2019 Increase in State Aid Was Long Awaited,” International Falls Journal, Jun. 20, 2019, ttps://www.ifallsjournal.com/news/local/for-minnesota-cities-and-counties-the-increase-in-state-aid/article_374e0f79-8b28-56b8-86b5-5e9a7a9a5e97.html.

[36] Assumes a 4.5 percent mortgage interest rate and does not include any property taxes or insurance costs.

[37] National Association of Realtors, “County Median Home Prices and Monthly Mortgage Payment,” https://www.nar.realtor/research-and-statistics/housing-statistics/county-median-home-prices-and-monthly-mortgage-payment.