Key Findings

- The Alternative Minimum TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. (AMT) requires a subset of taxpayers to compute their income tax liability twice—once under the ordinary individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. , and again under the AMT that allows fewer tax preferences—and pay whichever tax is highest.

- The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) increased the AMT’s exemption and exemption phaseout. These reforms will reduce the number of taxpayers that pay the AMT to an estimated 200,000 each year through 2025, down from 5 million in 2017.

- The AMT increases income tax compliance costs for taxpayers. TCJA reforms limited the number of taxpayers filing AMT returns, saving an estimated $4.6 billion in AMT-related compliance costs.

- The number of AMT taxpayers will increase again in 2026, from about 200,000 to 7 million when the TCJA’s individual income tax reforms expire. This will increase compliance costs for taxpayers.

- Removing one individual income tax—either the ordinary individual income tax or the tax currently structured as the AMT— would eliminate compliance burdens stemming from a system that subjects taxpayers to two different income taxes.

- Alternatively, policymakers could make the TCJA’s expanded exemption and exemption phaseout threshold permanent. This option would limit the number of taxpayers subject to the AMT and reduce AMT revenue. Taxpayers would still be subject to compliance burdens created by having to calculate two different income taxes.

Introduction

In 1969, U.S. Treasury Secretary Joseph Barr testified that in 1966, 155 high-income people paid zero income tax. Instead of eliminating the tax preferences that enabled these taxpayers to reduce their taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. Taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. , Congress created a minimum tax—10 percent of certain tax preferences—to curb this tax avoidance. By 1982, Congress had ditched this first minimum tax but established a second, known today as the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT).[1]

The AMT requires a subset of taxpayers to compute their income tax liability twice—once under the ordinary individual income tax, and again under the AMT which allows fewer tax preferences—and pay whichever tax is highest. The AMT was intended to keep wealthy taxpayers from using too many tax preferences, but in recent decades, the AMT’s impact has spread to affect taxpayers throughout income groups.[2]

The AMT generates little revenue compared to the ordinary individual income tax but significantly increases tax code compliance burdens for a subset of taxpayers. It impacts not just those who pay the AMT but also those taxpayers who are required to calculate their AMT liability but end up paying more through the ordinary individual income tax.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

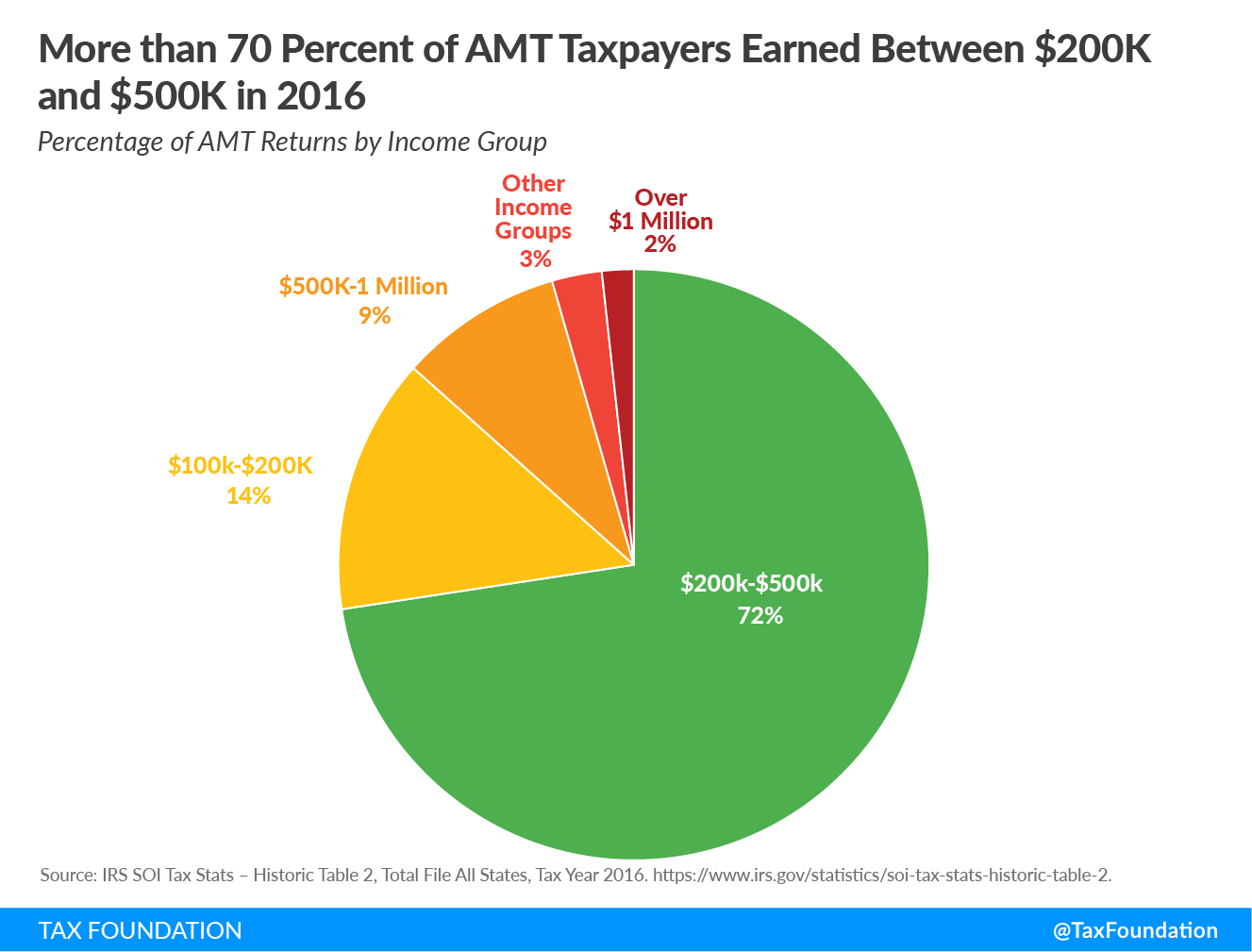

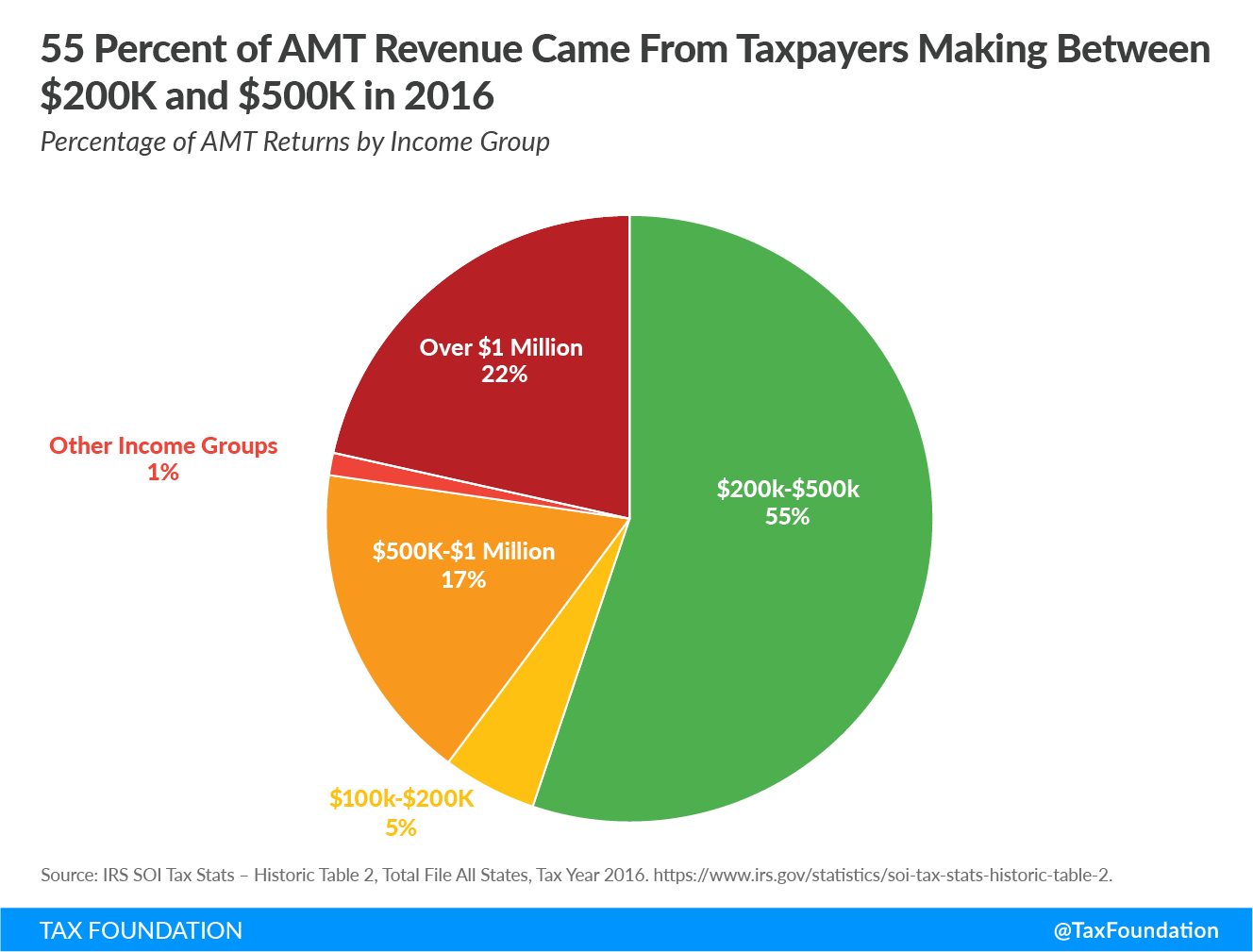

SubscribeThis analysis describes how the AMT works, as well as the types of taxpayers it affects. Using 2016 Internal Revenue Service (IRS) data (before the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, TCJA), we find the AMT’s burden is skewed toward a few high-tax states, and that more than 70 percent of AMT payers earned between $200,000 and $500,000. It then describes how the TCJA’s increases to the AMT’s exemption and exemption phaseout threshold will reduce the number of taxpayers who pay the AMT through 2025, as well as the impact the AMT will have on taxpayers if the TCJA’s AMT provisions expire in 2026 as scheduled.

The best way to reduce compliance burdens created by the AMT is to repeal one of the tax code’s income taxes because completing individual income taxes twice, under two sets of rules, is particularly burdensome for taxpayers. Alternatively, policymakers could make the TCJA’s expanded exemption and exemption phaseout threshold permanent. This would limit the number of AMT payers subject to the tax but reduce federal revenue and retain the tax code complexity that comes from requiring some taxpayers to comply with two different income taxes.

How the AMT Works

To understand the AMT, you must understand how taxpayers compute their ordinary individual income tax liability. The ordinary individual income tax allows taxpayers to reduce their Adjusted Gross IncomeFor individuals, gross income is the total of all income received from any source before taxes or deductions. It includes wages, salaries, tips, interest, dividends, capital gains, rental income, alimony, pensions, and other forms of income. For businesses, gross income (or gross profit) is the sum of total receipts or sales minus the cost of goods sold (COGS)—the direct costs of producing goods, including inventory and certain labor costs. (AGI) in two ways. Taxpayers can either itemize their deductions and pick specific tax preferences to lower their AGI, or taxpayers can take one larger deduction, called the standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. Taxpayers who take the standard deduction cannot also itemize their deductions; it serves as an alternative. , which allows individuals to reduce their AGI by $12,200 in 2019 ($24,400 for those married filing jointly). Once taxpayers calculate their AGI, they are taxed according to a progressive income tax rate schedule, with a top rate of 37 percent levied on income above $510,300.[3]

Each year, a subset of these ordinary individual income taxpayers find they have to calculate their income tax liability again under the AMT. Out of this group, an even smaller subset of taxpayers—just over 5 million in 2017[4]—have to pay a bit more in income taxes because their AMT liability exceeds their ordinary individual income tax liability.

The first step is figuring out whether AMT liability needs to be computed. Some taxpayers are automatically required to compute their AMT for taking certain tax preferences under the ordinary individual income tax, such as if a taxpayer excluded private activity bond interest or deducted intangible drilling costs from their taxable income. Others must complete a series of income tests to see whether they have to calculate their AMT liability.[5]

Once a taxpayer knows they have to compute their AMT liability, the next step is to figure out their Alternative Minimum Taxable Income (AMTI). In general, the AMT eliminates or reduces the value of tax preferences taken under the ordinary individual income tax.[6] The standard deduction, as well as certain itemized deductions, such as the deduction for state and local taxes (SALT) paid, cannot reduce AMTI.[7] Other expenses that are fully deductible under the ordinary individual income tax must be capitalized and amortized, such as costs related to the circulation of newspapers and mining.[8]

After establishing AMTI, the taxpayer is entitled to an exemption worth $71,700 for unmarried individuals, and $111,700 for those married, filing jointly in 2019. This exemption allows individuals to exclude the first $71,700 of AMTI from taxation, and only income beyond this exemption is taxed.[9] However, the AMT has an exemption phaseout that kicks in when an individual’s AMTI exceeds $510,300 ($1,020,600 for married couples). Once a taxpayer’s income passes this threshold, the amount of income a taxpayer can exclude from their AMTI declines by $0.25 for every dollar of income beyond the exemption phaseout threshold until the taxpayer’s exemption is eliminated.[10]

|

Source: Amir El-Sibaie, “2019 Tax Brackets,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 28, 2018. |

||

| Filing Status | Exemption Amount | Exemption Phaseout Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Unmarried Individuals | $71,700 | $510,300 |

| Married Filing Jointly | $111,700 | $1,020,600 |

After figuring out their AMTI and applying the exemption, taxpayers are taxed at a rate of 26 percent on AMTI below $191,500 ($95,750 for unmarried), and a rate of 28 percent on all AMTI in excess of $191,500 ($95,750 for unmarried).[11] Taxpayers then pay either their ordinary individual income tax liability or their AMT liability, whichever is greater.

Who the AMT Impacts

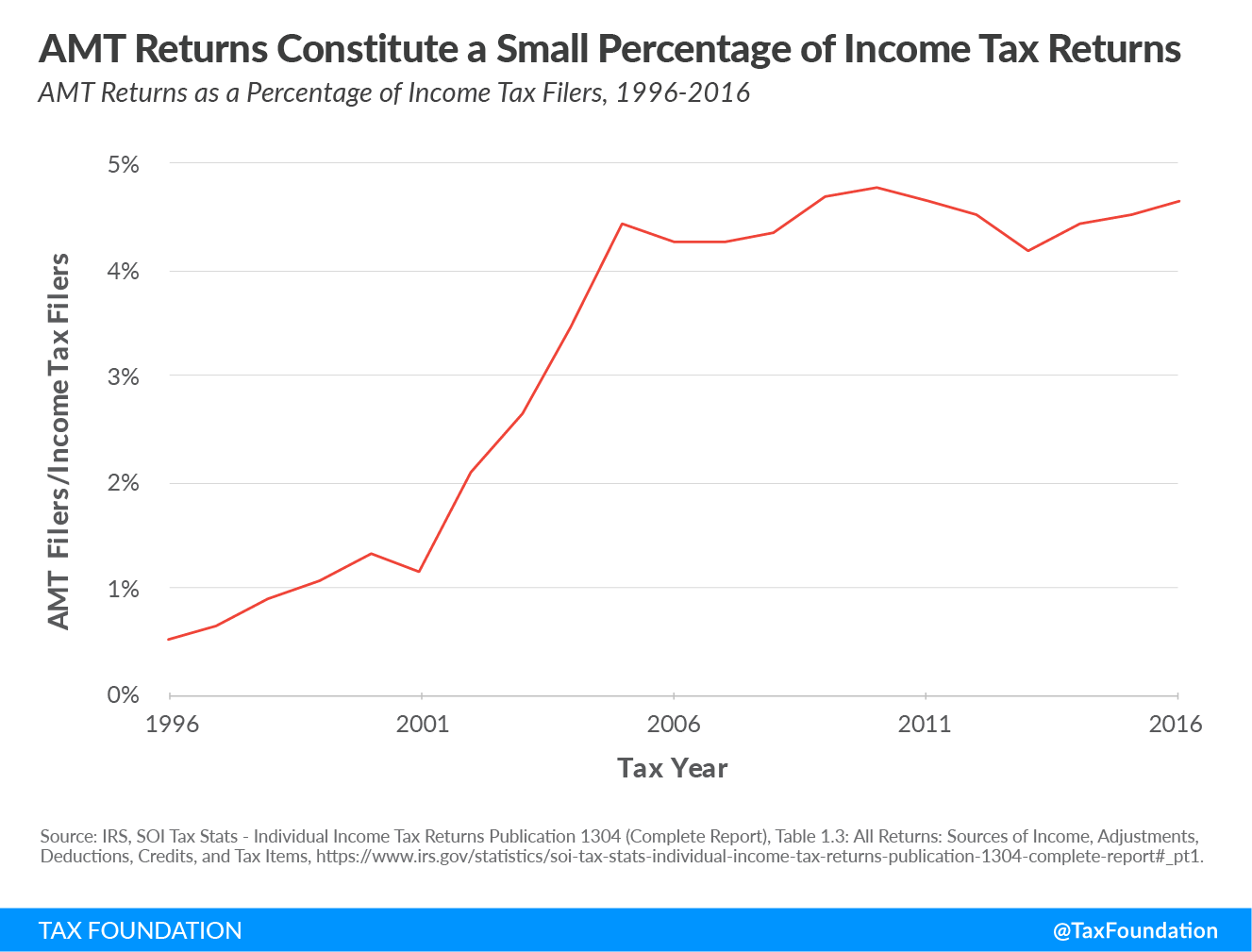

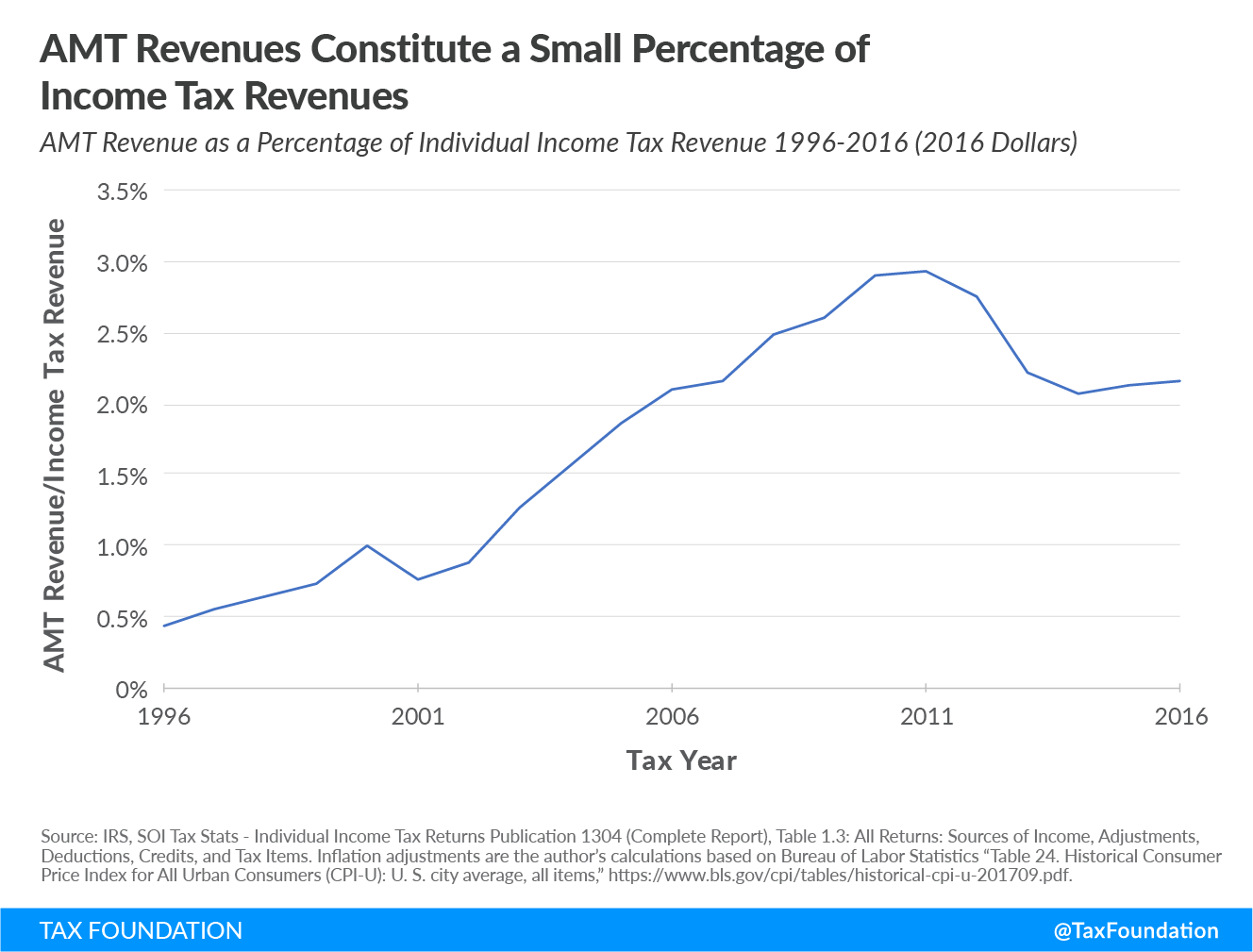

Historically, the number of AMT returns and revenue has been small relative to the number of tax filers and the revenue generated by the individual income tax. Since 1996, the number of AMT returns as a percentage of individual income tax returns has not surpassed 5 percent, while AMT revenue as a percentage of individual income tax revenue has not surpassed 3 percent.

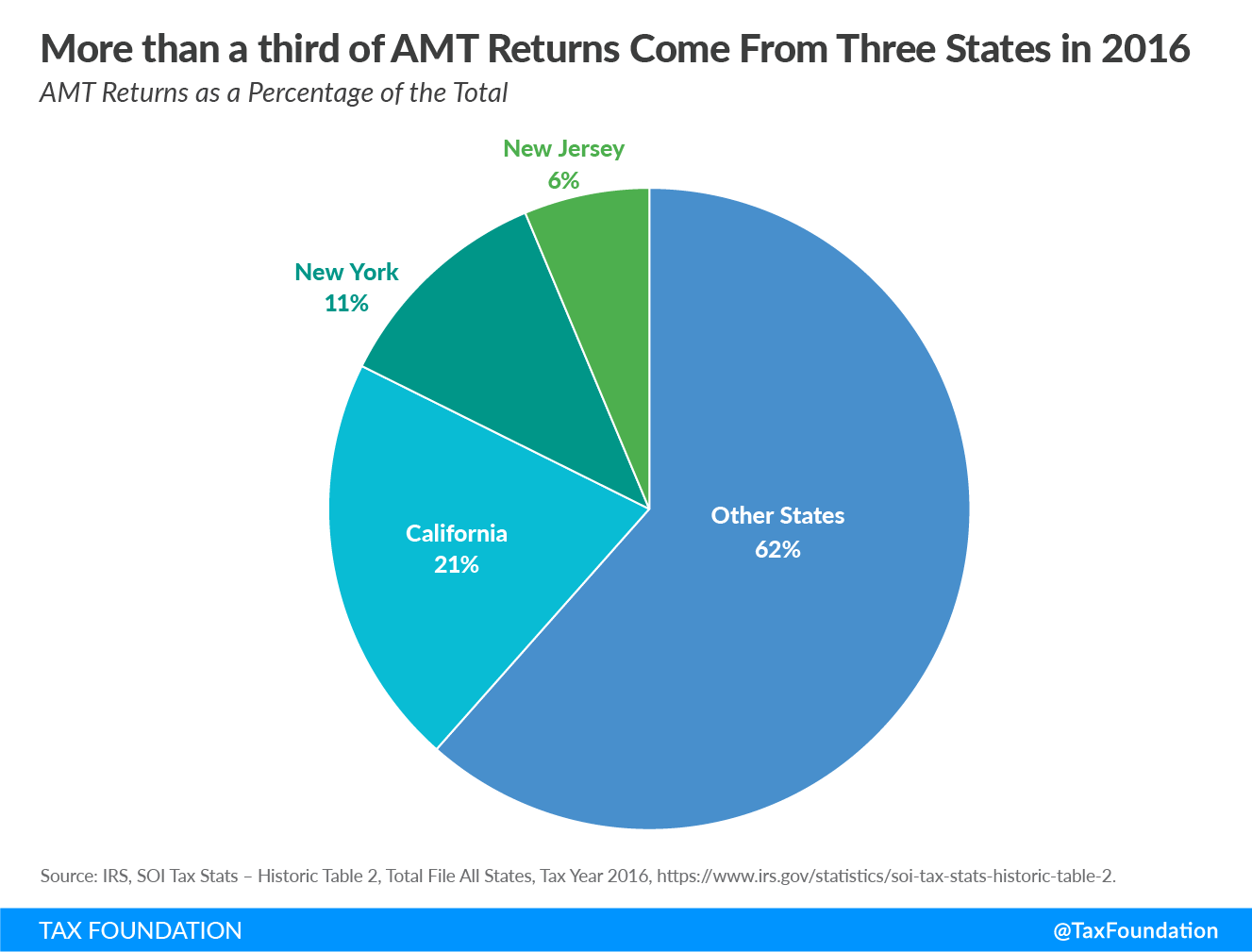

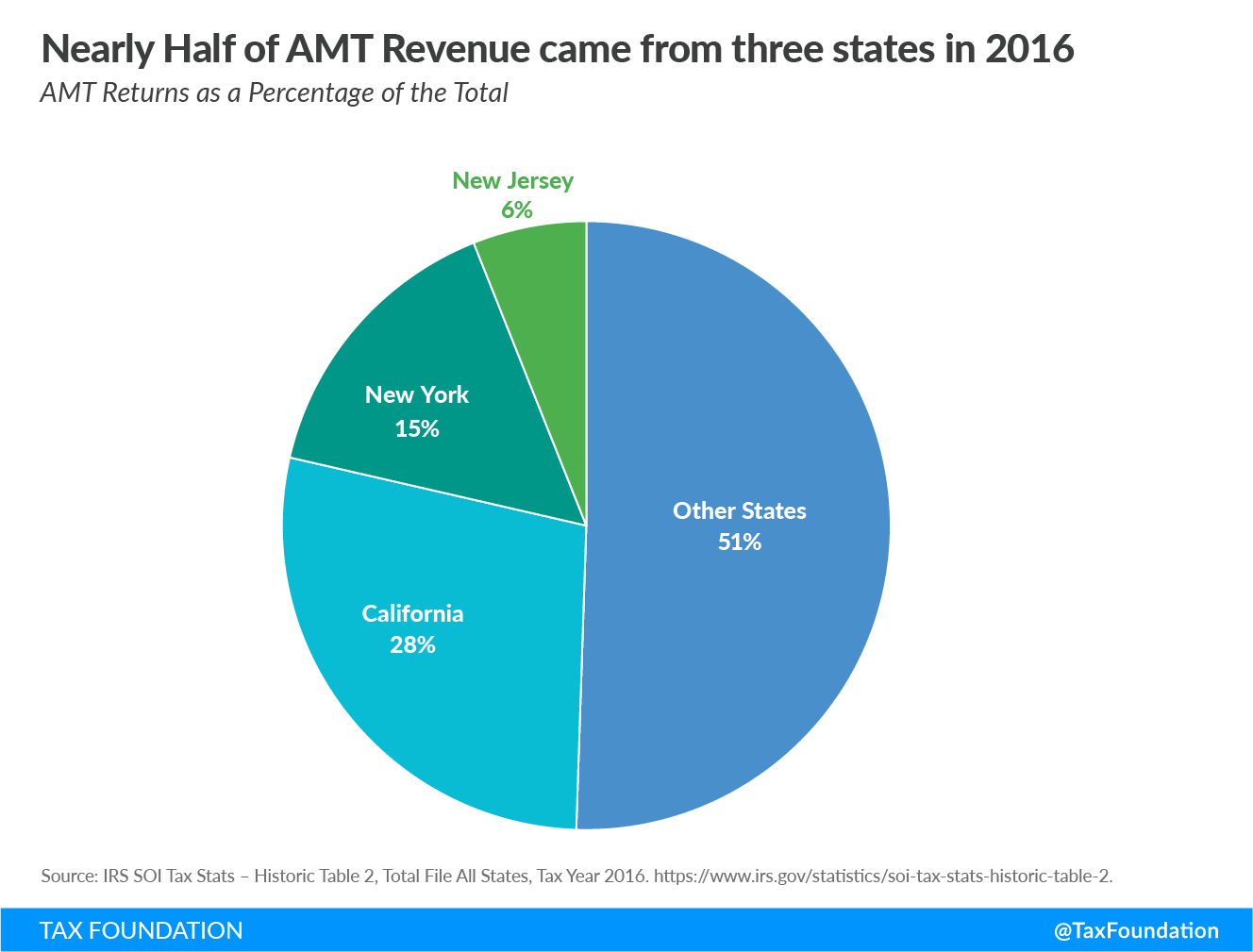

A few states make up a large portion of AMT filers and revenue. In 2016, California, New York, and New Jersey made up more than a third of AMT filers and generated almost half of all AMT revenue. One reason for this is that the AMT disallows the SALT deduction. Taxpayers in these relatively high-tax states[12] are unable to deduct their state and local taxes from their AMTI, which can push a taxpayer’s AMT liability beyond their ordinary individual income tax liability, resulting in more taxpayers paying the AMT.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeIn 2016, taxpayers earning between $200,000 and $500,000 in income comprised 72 percent of AMT taxpayers and 55 percent of AMT revenue, while taxpayers making between $100,000 and $200,000 comprised 14 percent of AMT filers and 5 percent of AMT revenue. The wealthiest income group, or those making more than $1 million annually, comprised just under 2 percent of all AMT taxpayers but accounted for 22 percent of AMT revenue.

The TCJA Has Reduced the Number of AMT Taxpayers Through 2025

The TCJA increased the AMT’s exemption for married filers from $84,500 to $109,400 (from $54,300 to $70,300 for individuals), and the AMT’s phaseout threshold from $160,900 to $1 million for married filers ($120,700 to $500,000 for individuals).[13]

This expanded exemption allows taxpayers calculating their AMT liability to exclude more income from taxation. The expanded exemption phaseout threshold allows more taxpayers to retain their full exemption for longer. This is because more taxpayers are now below the higher income level at which the exemption phaseout kicks in.

These reforms are expected to reduce the number of taxpayers paying the AMT to an estimated 200,000 each year through 2025, down from 5 million in 2017.[14] These reforms will reduce AMT revenue by an estimated $637 billion from 2018 to 2027.[15]

It’s worth highlighting that the AMT interacts with itemized deductions taken under the ordinary individual income tax. Because the expanded AMT exemption and exemption phaseout threshold limit the number of AMT payers, these reforms increase the likelihood taxpayers will benefit from itemized deductions, such as the SALT deduction that was capped by the TCJA at a non-inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. -adjusted $10,000.[16]

The TCJA Has Temporarily Reduced the AMT’s Compliance Burden

While the TCJA limited the number of actual AMT taxpayers, it’s important to understand that the AMT impacts a broader swath of taxpayers with compliance costs by making them comply with two separate income taxes. The IRS’s Taxpayer Advocate notes the AMT almost doubles the compliance costs of filing a federal income tax return, increases tax penalties, and reduces voluntary compliance.[17] The TCJA’s individual income tax reforms, which reduced the number of taxpayers who will have to calculate their AMT liability from an estimated 10 million to 1 million,[18] will save taxpayers an estimated $4.6 billion in AMT related compliance costs.[19]

However, the number of AMT taxpayers and revenue will increase from 2025 to 2026—from about 200,000 taxpayers to 7 million, and from approximately $6 billion in revenue to over $60 billion—when the TCJA’s AMT reforms expire.[20] This will cause compliance costs to increase and direct more taxpayer resources toward tax compliance instead of more productive activities.[21]

Possibilities for Reform

While the AMT generates far less revenue than the ordinary individual income tax, the AMT is particularly costly because it doubles the burden of filing income taxes for some taxpayers.

Policymakers could eliminate both the costs of and need for the AMT by removing tax expenditures that allow taxpayers to reduce their taxable income. In some cases, tax expenditures are special preferences for particular kinds of economic activity that deserve elimination in order to broaden the income tax’s base and fund broader tax relief. But other tax expenditures are more complicated, such as the reduced rate of tax for dividends and long-term capital gains. This policy mitigates the double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. of investment income and moves the U.S. tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. closer to a consumption taxA consumption tax is typically levied on the purchase of goods or services and is paid directly or indirectly by the consumer in the form of retail sales taxes, excise taxes, tariffs, value-added taxes (VAT), or income taxes where all savings are tax-deductible. base that would tax income once.[22]

Eliminating tax expenditures requires careful evaluation of which are worth retaining and which should go. Eliminating all tax preferences would also be politically difficult because interest groups are effective at defending the tax expenditures that benefit them.[23]

Instead, policymakers could consider eliminating one of the income taxes. Counterintuitively, eliminating the AMT could reduce both revenue on a dynamic basis compared to a static basis as well as the size of the economy, by increasing marginal tax rates on a taxpayer’s last dollar of income. Instead of some taxpayers paying a top rate of 28 percent, as they do currently under the AMT, all taxpayers would be required to pay marginal tax rates as high as 37 percent. This would reduce incentives to work and invest, both of which are important to the economy.[24] And in many ways, the AMT’s broader base, fewer tax bracketsA tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. , and lower rates make it a better structured tax than the ordinary individual income tax.[25]

Absent broad reform, policymakers could make the TCJA’s expanded exemption and exemption phaseout threshold permanent. This would reduce federal revenue by an estimated $288 billion between 2019-2028, but it would reduce the number of AMT payers permanently relative to current law. Some taxpayers would still be subject to costs of complying with two separate income taxes.

Conclusion

Although Congress intended the AMT to be a tax on wealthy taxpayers, for much of its history it has subjected middle-income taxpayers in high-tax states to heavy compliance burdens. TCJA reforms that have increased the AMT’s exemption and exemption phaseout threshold will shield some taxpayers from the AMT through 2025, but the number of taxpayers impacted will increase in 2026 when the TCJA’s individual income tax reforms expire.

Repealing the AMT or replacing the ordinary individual income tax with what is currently the AMT would resolve compliance costs that stem from calculating income taxes twice. Alternatively, policymakers could make the TCJA’s expanded exemption and exemption phaseout threshold permanent. This would reduce federal revenue but limit the number of AMT payers subject to the tax permanently relative to current law.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeNotes

[1] 26 U.S. Code § 55. For more on the history of the AMT, see Leonard E. Burman, “The Alternative Minimum Tax: Assault on the Middle Class,” Tax Policy Center, Oct. 29, 2007, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/alternative-minimum-tax/full.

[2] “The Individual Alternative Minimum Tax,” Congressional Budget Office, Jan. 15, 2010, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/111th-congress-2009-2010/reports/01-15-amtbrief.pdf.

[3] Amir El-Sibaie, “2019 Tax Brackets,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 28, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/2019-tax-brackets/.

[4] Internal Revenue Service Statistics of Income, “Table 1. Individual Income Tax Returns, Preliminary Data for Tax Years 2016 and 2017: Selected Income and Tax Items, by Size of Adjusted Gross Income,” https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/17in01pl.xls.

[5] “Alternative Minimum Tax: An Overview of Its Rationale and Impact on Individual Taxpayers,” United States General Accountability Office, August 2000, https://www.gao.gov/assets/240/230547.pdf, and “2018 Instructions for Form 6251,” The Internal Revenue Service, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/i6251.pdf.

[6] Melinda Garvin, “Alternative Minimum Tax Pains!” National Association of Tax Professionals. https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-utl/03-Alternative%20Minimum%20Tax%20Pains.pdf. The ordinary individual income tax contained 173 types of tax expenditures—such as exemptions, deductions, and credits—that allowed taxpayers to lower their tax burden in 2018. See Robert Bellafiore, “Tax Expenditures Before and After the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 18, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-expenditures-pre-post-tcja/.

[7] “Overview of the Federal Tax System as in Effect for 2018,” Joint Committee on Taxation, Feb. 7, 2018, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5060.

[8] 2017 Instructions for Form 6251, The Internal Revenue Service. For more information on the benefits of expensing, or the ability to immediately deduct the cost of business inputs from taxable income, see Erica York and Alex Muresianu, “The TCJA’s Expensing Provision Alleviates the Tax Code’s Bias Against Certain Investments,” Tax Foundation, Sept. 5, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/tcja-expensing-provision-benefits/.

[9] This phaseout establishes a 35 percent top effective AMT tax rate (125 percent of 28 percent). See “What is the AMT?” in Tax Policy Center, Tax Policy Center Briefing Book: Key Elements of the U.S. Tax System, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/what-amt.

[10] Amir El-Sibaie, “2019 Tax Brackets.”

[11] Ibid.

[12] Jared Walczack, Scott Drenkard, Joseph Bishop-Henchman, “2019 State Business Tax Climate Index,” Tax Foundation, 2018, /wp-content/uploads/2018/09/2019-State-Business-Tax-Climate-Index.pdf.

[13] These numbers have since been adjusted for inflation. See Tax Policy Center, “What is the AMT?”

[14] “T18-0145 – Aggregate AMT Projections, 2016-2028,” Tax Policy Center, Oct. 2, 2018, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/baseline-alternative-minimum-tax-amt-tables-oct-2018/t18-0145-aggregate-amt.

[15] “Estimated Budget Effects of the Conference Agreement For H.R. 1, the ‘Tax Cuts And Jobs Act,’” Joint Committee on Taxation, Dec. 18, 2017, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5053.

[16] Scott Eastman, “The TCJA Cuts Taxes Across Every Income Level and Congressional District,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 30, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/tcja-cuts-taxes-across-every-income-level-and-congressional-district/.

[17] “Repeal the Alternative Minimum Tax,” Taxpayers Advocate Service, 2013, 298, http://www.taxpayeradvocate.irs.gov/2013-Annual-Report/downloads/Repeal-the-Alternative-Minimum-Tax.pdf.

[18] Internal Revenue Service, “Proposed Collection; Comment Request for Regulation Project: 83 FR 34698,” July 20, 2018, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/07/20/2018-15627/proposed-collection-comment-request-for-regulation-project.

[19] Erica York and Alex Muresianu, “The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Simplified the Tax Filing Process for Millions of Households.” Tax Foundation, Aug. 7, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-simplified-the-tax-filing-process-for-millions-of-households/#_ftn24.

[20] Tax Policy Center, “T18-0145 – Aggregate AMT Projections, 2016-2028.”

[21] Research suggests tax compliance costs range from $215 billion to $987 billion annually. See Jason J. Fichtner and Jacob M. Feldman, “The Hidden Costs of Tax Compliance,” The Mercatus Center at George Mason University, May 20, 2013, https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/Fichtner_TaxCompliance_v3.pdf.

[22] Robert Bellafiore, “Tax Expenditures Before and After the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

[23] Matthew Mitchell, “Overcoming the Special Interests That Have Ruined Our Tax Code,” in Adam J. Hoffer and Todd Hesbit (eds.), For Your Own Good: Taxes, Paternalism, and Fiscal Discrimination in the Twenty-First Century (Arlington, VA: Mercatus Center at George Mason University, 2018), https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/chapter_19.pdf.

[24] See Option 44, “Eliminate the Alternative Minimum Tax,” in Options for Reforming America’s Tax Code (Washington, DC: Tax Foundation, 2016). /wp-content/uploads/2016/06/TF_Options_for_Reforming_Americas_Tax_Code.pdf.

[25] For a discussion of this idea, see Michael Kinsley, “In Defense of the AMT,” The Washington Post, Oct. 20, 2007, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/10/19/AR2007101901577.html.

Share this article