Key Findings

- State taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. changes are not made in a vacuum. States often adopt policies after watching peers address similar issues. Several notable trends in tax policy have emerged across states in recent years, and policymakers can benefit from taking note of these developments.

- The enactment of the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) expanded many states’ tax bases and drove deliberations on tax conformity. At year’s end, only five states conform to an older version of the federal tax code, though many have yet to resolve issues raised by their tax conformity regimes.

- Several states experimented with mechanisms to allow their high-income taxpayers to avoid the new cap on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction, efforts cast into doubt–though not entirely ended–by draft U.S. Treasury regulations.

- Three states and the District of Columbia cut corporate taxes in 2018, with rate reductions pending in two other states. Reductions in other taxes on capital are ongoing as well, with Mississippi beginning the phaseout of its capital stock tax.

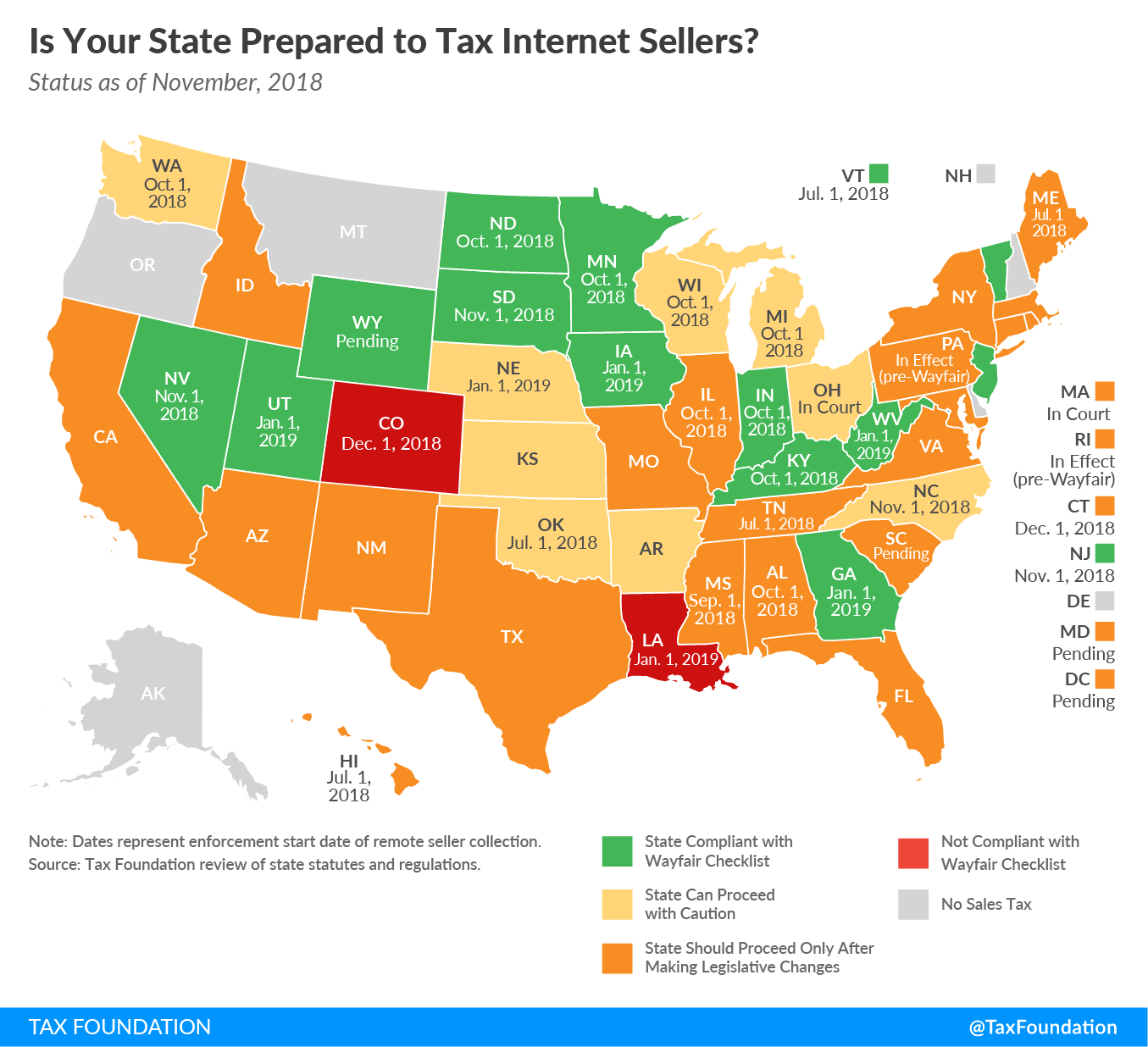

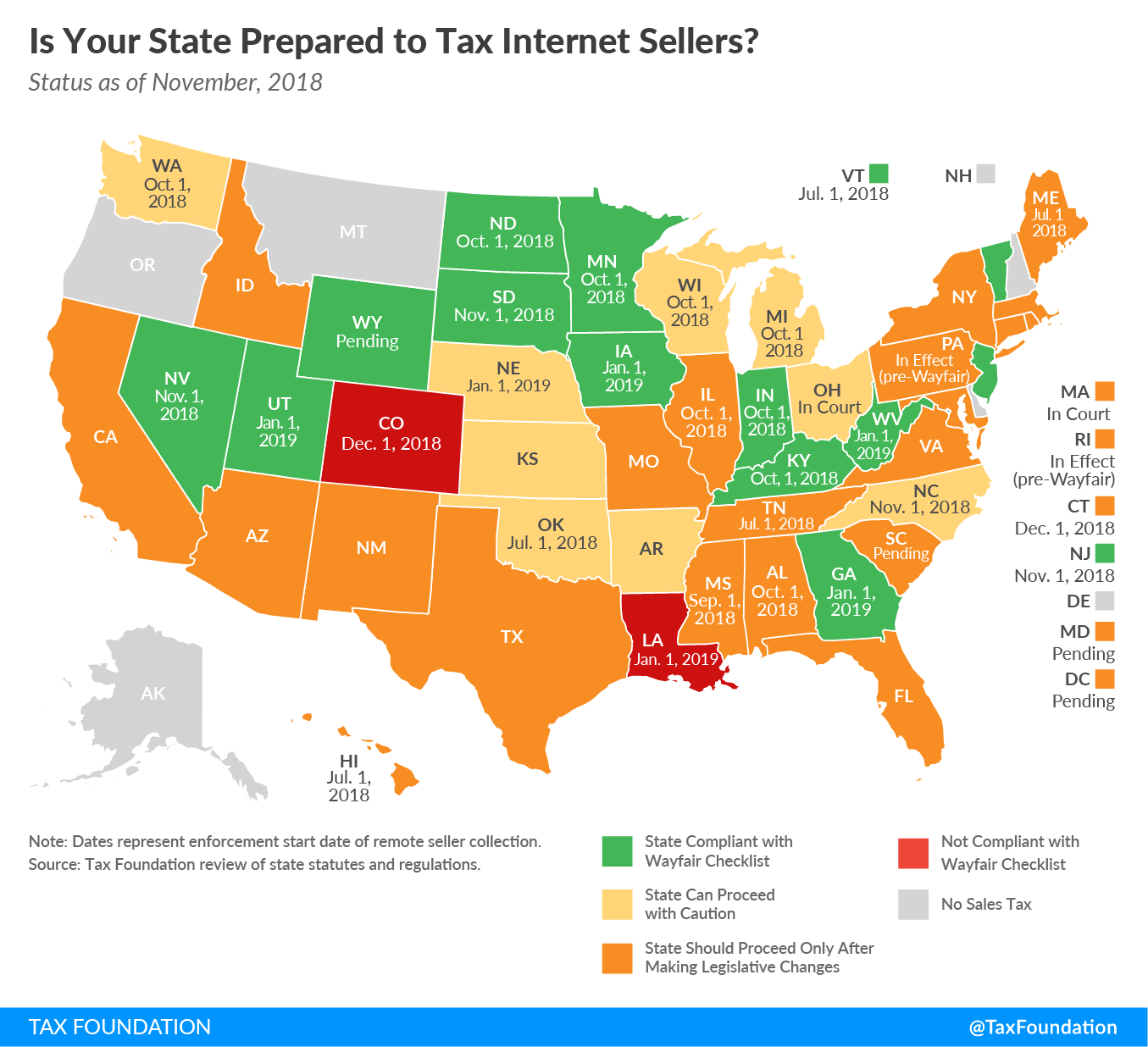

- The U.S. Supreme Court’s Wayfair v. South Dakota decision ushered in a new era of sales taxes on e-commerce and other remote sales, but many states have yet to implement the provisions the Court strongly suggested would protect such tax regimes from future legal challenges.

- A second state (Arizona) adopted a constitutional amendment banning the expansion of the sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. to additional services, with similar efforts–which have the effect of locking an outdated sales tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. in place–expected to emerge in other states in 2019 and beyond.

- A court ruling has states scrambling to legalize and tax sports betting, while shifting public attitudes continue to render the legalization and taxation of marijuana an attractive revenue option in a growing number of states. In 2018, seven states adopted sports betting taxes, while two legalized and taxed marijuana.

- States continue to grapple with the appropriate taxation, if any, of e-cigarettes, with two states adopting taxes at rates reflective of vapor products’ potential for harm reduction, while the District of Columbia increased its tax to a punitive 96 percent rate.

- Business head taxes came out of nowhere to become a key consideration for several cities, particularly those with thriving tech sectors.

- Consideration of gross receipts taxes continue as corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. revenues decline, though concerns about their economic effects have generally helped stave off their adoption.

- Two states repealed their estate taxes in 2018, continuing a decade-long trend away from taxes on estates and inheritances.

- Revenue triggers, a relatively modern innovation, again featured prominently in tax reform packages and will continue to do so.

Introduction

State tax policy decisions are not made in isolation. Changes in federal law, global markets, and other exogenous factors create a similar set of opportunities and challenges across states. The challenges faced by one state often bedevil others as well, and the proposals percolating in one state capitol often show up elsewhere. Ideas spread and policies can build their own momentum. Sometimes a trend emerges because one state consciously follows another, and in other cases, similar conditions result in multiple states trying to solve the same problem independently.

Identifying state tax trends serves a dual purpose: first, as a leading indicator providing a sense of what we can expect in the coming months and years, and second, as a set of case studies, placing ideas into greater circulation and allowing empirical consideration of what has and has not worked.

The adoption of the federal Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) and the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Wayfair v. South Dakota set off a chain reaction in state capitals, and the reaction to a Court decision on sports betting has been swift and enthusiastic in a growing number of states. As policymakers grapple with tax conformity under the TCJA, seek to craft Wayfair-compliant remote sales tax regimes, and figure out if and how to legalize and tax sports betting, they can and should learn from their peers.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeNot all trends are driven by the federal government, of course. Shifting public attitudes toward marijuana have many states contemplating legalization as a new revenue stream, while declining collections from corporate income taxes have states grasping for alternatives. Ideas tried in one state–be it tax triggers, business head taxes, or changes to the sales tax base–often crop up elsewhere. The past year contains tax policy story lines that provide insights on the year to come.

Some trends worth noting have been with us for years, while others are just emerging; some are promising, while others might be thought of as cautionary; and some are time-constrained reactions to exogenous factors, while others represent innovations other states may wish to adopt. In all cases, policymakers can benefit from greater awareness of these developments.

Income Taxes

Across the country, income tax policies–both individual and corporate–were heavily influenced by the enactment of federal tax reform. States grappled with how to conform to the provisions of the new tax law, and in some cases sought to help their taxpayers circumvent its effects. The past year also saw further corporate income tax rate reductions and the adoption of reforms intended to enhance the neutrality of individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. codes.

IRC Conformity Updates

Most states begin their own income tax calculations with federal definitions of adjusted gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total pre-tax earnings from wages, tips, investments, interest, and other forms of income and is also referred to as “gross pay.” For businesses, gross income is total revenue minus cost of goods sold and is also known as “gross profit” or “gross margin.” (AGI) or taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. , and they frequently incorporate many federal tax provisions into their own codes. The degree to which state tax provisions conform to the federal Internal Revenue Code (IRC) varies, as does the version of that code to which they conform. Some states have “rolling conformity,” meaning that they couple to the current version of the IRC, while others have “static conformity,” utilizing the IRC as it existed at some fixed date. Although exceptions exist, most states with static conformity update their conformity date every year as a matter of course.

The adoption of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) turned what had been routine into a serious policy deliberation. Most states stand to see increased revenue due to federal tax reform, with expansions of the tax base reflected in state tax systems, while corresponding rate reductions fail to flow down. The increase in the standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. It was nearly doubled for all classes of filers by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) as an incentive for taxpayers not to itemize deductions when filing their federal income taxes. , the repeal of the personal exemption, the creation of a deduction for qualified pass-through businessA pass-through business is a sole proprietorship, partnership, or S corporation that is not subject to the corporate income tax; instead, this business reports its income on the individual income tax returns of the owners and is taxed at individual income tax rates. income, the narrowing of the interest deduction, the cap on the state and local tax deductionA tax deduction is a provision that reduces taxable income. A standard deduction is a single deduction at a fixed amount. Itemized deductions are popular among higher-income taxpayers who often have significant deductible expenses, such as state and local taxes paid, mortgage interest, and charitable contributions. (which affects state deductions for local property taxes), adjustments to the treatment of net operating losses, and enhanced cost recoveryCost recovery is the ability of businesses to recover (deduct) the costs of their investments. It plays an important role in defining a business’ tax base and can impact investment decisions. When businesses cannot fully deduct capital expenditures, they spend less on capital, which reduces worker’s productivity and wages. for machinery and equipment purchases, and even some of the provisions on the taxation of international income, flow through to the tax codes of some states—in different combinations, depending on the federal code sections to which they are coupled.[1]

States, therefore, were faced with choices. They could continue to conform to an older version of the IRC to avoid these revenue implications.[2] Alternatively, if conforming to the IRC post-TCJA, they could decouple from revenue-raising provisions, cut tax rates or implement other tax reforms to offset revenue increases, or do nothing, keeping the additional revenue.

The extent to which this is true (and indeed in some cases, whether it is true) depends on the federal tax provisions to which a state conforms. In 2018, five states–Georgia, Iowa, Missouri, Utah, and Vermont–adopted rate cuts or other reforms designed, at least in part, as a response to the expectation of increased revenue due to federal tax reform. Others, like Maryland and New York, rolled back some–but not all–of the federal changes to reduce the added state tax burden. States have generally been more willing to roll back changes to the individual income tax than to the corporate income tax. Finally, other states have been satisfied to retain the additional revenue, at least for now.

As of December 15, 2018, 32 states and the District of Columbia conformed to a version of the IRC which includes the reforms adopted under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (14 through updates to static conformity statutes). Another five states (Arizona, California, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Virginia) conform to an older version of the code or expressly exclude changes implemented as part of the TCJA, while the remaining states either forgo an individual income tax or use state-specific calculations of income.[3] Many of these states have yet to grapple with the revenue implications of their decisions, and most have provided limited guidance on incorporated elements of the new system of international taxation, meaning that conformity issues will continue to dominate many legislatures in 2019.

SALT Deduction Cap Avoidance

By capping the state and local tax deduction (SALT) at $10,000, the new federal law set off a flurry of legislative activity in high-income, high-tax states. Policymakers had no shortage of inventive, if sometimes legally dubious, workarounds from which to choose. In broad terms, however, these efforts fell under three headings: (1) recharacterization of state and local tax payments as charitable contributions, thus evading the cap; (2) optional participation in an employer-remitted payroll taxA payroll tax is a tax paid on the wages and salaries of employees to finance social insurance programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance. Payroll taxes are social insurance taxes that comprise 24.8 percent of combined federal, state, and local government revenue, the second largest source of that combined tax revenue. regime to offset employees’ individual income tax liability, shifting payments to an uncapped arena; and (3) converting pass-through business owners’ income tax liability into an entity-level tax not subject to the cap. Each approach suffers from some combination of legal, practical, and distributional shortcomings.[4]

This trend is not without irony, as it involves some of the nation’s most progressive states–like New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut–taking great pains to reduce liability for their highest-income taxpayers even though most of these taxpayers already received a substantial tax cut under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut established an option of charitable contribution in lieu of taxes, which would be disallowed under draft guidance from the U.S. Department of the Treasury,[5] while a similar effort in California was vetoed by Gov. Jerry Brown (D). Connecticut and Wisconsin enacted an entity-level tax on S corporationAn S corporation is a business entity which elects to pass business income and losses through to its shareholders. The shareholders are then responsible for paying individual income taxes on this income. Unlike subchapter C corporations, an S corporation (S corp) is not subject to the corporate income tax (CIT). s and partnerships, with a countervailing credit against the individual income tax liability of owners, to circumvent the cap, though in addition to any potential legal defects, the new tax can significantly complicate taxation for small businesses with income earned in, or partners located in, other states. And New York created an optional business payroll tax which would yield a credit against employees’ income tax liability, for much the same purpose—though with the further implication that taxpayers could receive the benefit of the standard deduction and a reduction in federal tax liability intended to replicate the state and local tax deduction, otherwise only available to filers who itemize.

It is possible that the pending Treasury guidance will put an end to the charitable contribution workarounds, but given the multiple permutations, it seems more likely that these efforts will continue at least another year or two.

Corporate Income Tax Rate Reductions

Corporate income taxes represent a small and shrinking share of state revenue, the product of a long-term trend away from C corporations as a business entity and ever-narrowing bases due to the accumulation of tax preferences. (The pass-through sector has grown dramatically, both in raw numbers and share of business income, over the past few decades, due in no small part to the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which lowered the top individual income tax rate from 50 to 28 percent.[6])

In 2018, Connecticut permitted a 20 percent corporate income surtaxA surtax is an additional tax levied on top of an already existing business or individual tax and can have a flat or progressive rate structure. Surtaxes are typically enacted to fund a specific program or initiative, whereas revenue from broader-based taxes, like the individual income tax, typically cover a multitude of programs and services. on large businesses to decline to 10 percent, bringing the top marginal rate from 9.0 to 8.25 percent. The reduction was scheduled as part of an extension of the surtax adopted in 2015. In New Mexico, the top marginal corporate income tax rate declined from 6.2 to 5.9 percent, the culmination of a multiyear phasedown beginning with a top rate of 7.6 percent in 2017. Indiana’s corporate rate declined to 5.75 percent, continuing a series of reductions that will culminate in a 4.9 percent rate in 2022. In the District of Columbia, the final phase of a multiyear tax reform package saw the corporate franchise tax rate decline from 8.75 to 8.25 percent.[7]

Meanwhile, future rate reductions are scheduled in New Hampshire and North Carolina in 2019, and Missouri in 2020. New Jersey was the anomaly this year, hiking its corporate income tax.[8]

Although few states have repealed their corporate income taxes, their volatility, narrowing bases, economic impacts, and modest contribution to state revenues have all contributed to states’ decisions to reduce reliance on the tax.

|

Source: Tax Foundation research. |

|||

| State | 2012 | 2018 | Scheduled |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Arizona |

6.968% | 4.9% | — |

|

Idaho |

7.6% | 7.4% | — |

|

Illinois |

9.5% | 7.75% | — |

|

Indiana |

8.5% | 5.75% | 4.9% |

|

Missouri |

6.25% | 6.25% | 4.0% |

|

New Hampshire |

8.5% | 8.2% | 7.9% |

|

New Mexico |

7.6% | 5.9% | — |

|

New York |

7.1% | 6.5% | — |

|

North Carolina

|

6.9% | 3.0% | 2.5% |

|

North Dakota |

5.2% | 4.31% | — |

|

Rhode Island |

9.0% | 7.0% | — |

|

West Virginia |

7.75% | 6.5% | — |

|

District of Columbia |

9.975% | 8.25% | — |

Federal Deductibility Limitations

Under federal deductibility, taxpayers can deduct federal tax liability from income in calculating their state tax liability. This provision, which only exists in six states, is the mirror image of the federal government’s state and local tax (SALT) deduction and is based on estimated liability to avoid a circular interaction with the federal government’s state and local tax deduction. It has the perverse effect of penalizing whatever the federal government incentivizes, and vice versa, as anything which incurs greater tax liability at the federal level reduces tax burdens at the state level.

The resulting distributions are convoluted and difficult to defend: things like having children, investing in your small business, or earning capital gains income, because they receive preferential tax treatment at the federal level, face higher effective rates in states with federal deductibility. Meanwhile, federal deductibility creates the mirror image of the federal government’s progressive rate structure. A graduated-rate state income tax and federal deductibility operate at cross-purposes with each other, but the result is not a flat taxAn income tax is referred to as a “flat tax” when all taxable income is subject to the same tax rate, regardless of income level or assets. but rather one where effective rates on marginal income fluctuate irrationally.

Only six states still permit a deduction for federal taxes paid, and thanks to reforms adopted this year, one of those states (Iowa) is set to repeal it entirely, and another (Missouri), which already caps the value of the deduction, adopted further restrictions on its availability. In both cases, federal deductibility is being traded for rate reductions and other structural reforms. Until recently, the remaining states offering federal deductibility thought of it as a “third rail.” Iowa’s breakthrough may well have changed that, paving the way for reforms in Missouri and potentially elsewhere.

Sales Taxes

In 2018, the Supreme Court upended the sales tax landscape by paving the way for states to apply their tax to remote sellers not physically present in the state. This outcome created new revenue opportunities for states, while simultaneously inducing them to simplify and modernize their tax codes. Unfortunately, some states continue to push in the wrong direction, resisting efforts to bring their sales tax systems in line with modern consumption patterns.

Remote Sales Tax Collection Regimes

E-commerce represented 9.8 percent of all retail sales in the third quarter of 2018,[9] a slice of the retail pie that states are increasingly able to capture in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s decision in Wayfair v. South Dakota, which struck down the physical presence requirement for substantial nexus.[10] After years of chafing at Quill, states won a major victory in court—and are now lining up to begin collecting.

Some states have incorporated tax simplification provisions recommended in the Wayfair decision–what we have termed the “Wayfair Checklist”[11]–while others are moving forward with collections even though their tax codes are vulnerable to legal challenges on the grounds that they unduly burden interstate commerce. The factors present in South Dakota’s law, which the Supreme Court strongly suggested would protect it against any further legal challenges, include:

- A safe harbor for those only transacting limited business in the state;

- An absence of retroactive collection;

- Single state-level administration of all sales taxes in the state;

- Uniform definitions of goods and services;

- A simplified tax rate structure;

- The availability of sales tax administration software; and

- Immunity from errors derived from relying on such software.[12]

As of December 15, 2018, 34 states have adopted laws or regulations to tax remote sales, with legislation or administrative action pending in several others. Twelve of these states are clearly compliant with the Wayfair Checklist, and many others are undertaking improvements to shore up their remote sales tax regimes. However, some states–Louisiana is a particularly egregious example–are proceeding despite tax codes which impose significant burdens on remote sellers and raise serious legal issues. Colorado, another state with serious compliance issues, recently postponed remote sales tax collections.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeIn 2019, we can expect additional states to expand into the taxation of remote sales and should anticipate litigation in states which take too many shortcuts in their efforts to capture that revenue. Ultimately, the framework for those collections might have to be established over time through the courts, though states can and should avoid this by modeling their regime on the South Dakota law upheld by the Supreme Court.

Sales Tax Base-Narrowing Measures

Public finance scholars overwhelmingly agree that a well-designed sales tax base should extend to both goods and services while excluding business inputs.[13] Voters, however, are often skeptical of broadening the sales tax base, and we may be witnessing the beginning of a trend of tying policymakers’ hands on expansion to new services.

The exclusion of many services from most states’ sales tax bases is a historical accident, the result of sales taxes being implemented in an era when consumption was dominated by the sale of tangible goods and where the rudimentary tax systems in place would have made the taxation of services difficult. Today, however, services comprise more than two-thirds of all consumption, meaning that the sales tax omits most of what people purchase. Unchecked, this continual base erosion forces policymakers to raise rates or turn to other, often less efficient, taxes to raise the necessary revenue. Exempting services from the sales tax is also regressive, since services are consumed in greater proportion by wealthier households.

Ideally, policymakers should be exploring the expansion of the sales tax base, which can often help pay for other, much-needed tax reforms. Last year, however, Missouri voters ratified a constitutional amendment prohibiting base broadeningBase broadening is the expansion of the amount of economic activity subject to tax, usually by eliminating exemptions, exclusions, deductions, credits, and other preferences. Narrow tax bases are non-neutral, favoring one product or industry over another, and can undermine revenue stability. to any service not already taxed, and this year, voters in Arizona followed suit.[14] On the heels of these victories at the ballot box, opponents of service taxation are already gearing up for similar ballot measures in other states.

These constitutional prohibitions prevent states from modernizing their sales tax, which in turn forces policymakers to turn to far less economically efficient sources of revenue.

Excise TaxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. es

Shifting public attitudes, a changing legal environment, and product innovations made are responsible for a spate of new or revised “sin” taxes on marijuana, sports betting, and vapor products, a trend likely to continue in coming years.

Taxation of Sports Betting

A U.S. Senator from New Jersey, basketball great Bill Bradley, was responsible for the 1992 legislation banning sports betting in the 46 states that had not already legalized it.[15] Earlier this year, a court case brought by New Jersey got that law struck down as unconstitutional. The Supreme Court’s decision in Murphy v. National Collegiate Athletic Association opened the door to the legalization and taxation of sports betting, and states have wasted no time in entering the space.

Sports betting has changed since the 1992 law was enacted, particularly with the rise of daily fantasy sports. Not only can bettors lay odds on a team winning straight up or against the spread, but they can engage in fast-paced in-game betting. Will the next touchdown be scored by a wide receiver? Will the next shot be a three-pointer?

These in-game bets enhance the importance of the integrity of in-game data, at least theoretically. That has been the crux of argument advanced by professional sports leagues–particularly Major League Baseball (MLB) and the National Basketball Association (NBA)– for so-called “integrity fees,” in which as much as 1 percent of the “handle” (the total amount of bets taken) would be remitted to the league to offset the costs of maintaining the data on which bets are based, and in compensation for generating the product (the games themselves) which makes betting possible.

Many policymakers have questioned the justifications for these integrity fees. (Are existing league statistics somehow unreliable?) Some proponents are increasingly calling them royalties, which comes closer to explaining the real basis of the claim. Actual royalties, though, would not require the state to act as collector; unfortunately for sports leagues, there is little legal precedent to support the notion that statistics and scores constitute intellectual property. Thus far, states have spurned league efforts to insert them into sports betting legalization bills, though that may change with pending legislation in Michigan and Missouri.

States which have already legalized casino gambling are particularly likely to permit sports betting, but they should be conservative in their revenue estimates. Daily fantasy sports and other online options largely out of reach of state tax regimes will limit taxable betting activity, and collections are likely to be modest. If states adopt particularly high taxes–like the 51 percent of gross gaming revenues (revenues less winnings) sought by Rhode Island, or the 34 percent chosen in Pennsylvania[16]—they are likely to discourage in-person betting in competition with online alternatives which are far harder to tax. Or even competition down the road: Pennsylvania’s neighbor to the east, New Jersey, plans to tax sports betting at casinos and race tracks at 8 percent.[17]

Similar to issues raised by marijuana legalization, brick-and-mortar sports betting facilities will be competing with black and gray markets, and setting tax rates too high could keep bettors in untaxed markets. Initially, moreover, a state which legalizes sports betting may attract bettors across state lines, but this effect should dissipate as more states legalize wagering on sports. As of December 15, 2018, seven states (Delaware, Mississippi, New Jersey, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and West Virginia) had legalized sports betting in addition to Nevada, which already had a substantial sports betting regime.[18] Measures are pending in about two dozen more states.

Legalization and Taxation of Marijuana

As public attitudes toward marijuana have changed, states are increasingly revisiting their statutes on the possession, sale, and taxation of marijuana. Many states now allow medical marijuana, others have decriminalized possession, and a small but growing number have legalized recreational marijuana. Thus far, every state which has legalized marijuana has done so in concert with the implementation of a new excise tax regime.

A marijuana-specific tax regime is not theoretically essential, as it could, post-legalization, simply fall under the state sales tax like most other consumer goods. The notion that marijuana (like tobacco products, alcohol, and select other goods) should have its own tax regime has, however, been largely uncontroversial. These taxes also fund the states’ marijuana regulatory regimes, though in all cases they raise revenue considerably in excess of these costs and help fund general governmental expenditures.

Heading into 2018, seven states (Alaska, California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington) had legalized recreational marijuana, while implementation of a voter-approved measure in Maine had been delayed.[19] Of these, Alaska imposed a volume-based excise tax at $50 per ounce, while the remaining states imposed ad valorem taxes, such as Oregon’s 17 percent tax on marijuana. California has a hybrid system which includes both a 15 percent ad valorem tax and flat per-ounce taxes on flowers and leaves.

This year, Michigan voters legalized recreational marijuana and imposed a 10 percent excise tax. Missouri voters, meanwhile, were given a menu of options: they could impose either a 4 or 15 percent tax via constitutional amendment, or a 2 percent tax with an initiated measure, each with revenue dedicated to a different set of priorities. Voters overwhelmingly selected the modest 4 percent rate.

North Dakota voters rejected marijuana legalization in November, but it is reasonable to expect that legalization will reach additional states each year, either at the ballot box or through legislation. Although legislation is pending or expected to be introduced in a number of states during the 2019 session, lawmakers across the country have demonstrated a marked preference for leaving the decision to voters at the ballot.[20]

Initially, excise taxes tended to be quite high. In 2016, the four states with recreational marijuana were Washington with a 37 percent excise tax, Colorado at 29 percent, and Alaska and Oregon at 25 percent. These rates may have been too high to drive out gray and black markets.[21] Since then, Alaska, Colorado, and Oregon have reduced marijuana tax burdens, and states which implemented marijuana excise taxes since then have tended to adopt lower rates. As more states contemplate marijuana legalization, they are likely to consider excise tax rates closer to those adopted in 2017 and 2018 than those set in 2016.

Taxation of Vapor Products

Nine states and the District of Columbia tax vapor products. E-cigarettes are themselves relatively new, and states have struggled to determine if and how to tax them. When smokers shift to vapor products, this reduces cigarette tax revenue, but given that a stated purpose of most tobacco taxes is to improve health outcomes and reduce health-related expenditures, the harm reduction associated with these alternative products must be taken into account. Taxing vapor products identically with, or even more heavily than, traditional tobacco products creates a disincentive for smokers to shift to a less harmful product.

This year, Delaware and New Jersey adopted volume-based excise taxes, at 5 and 10 cents per fluid milliliter, respectively, while the District of Columbia hiked its ad valorem tax to an astonishing 96 percent of wholesale price, a tax rate likely to discourage smokers from making the transition. As vapor products increase in popularity, more states are likely to consider taxing them.

Business Taxes

State and local governments continue to experiment with new (and often economically harmful) businesses taxes, though a couple of outmoded business taxes are on the way out.

Revival of Business Head TaxA head tax, also known as a poll tax or capitation, is a flat or uniform tax levied equally on every taxpayer. Unlike an income tax, it is a fixed amount and not based on how much one earns, nor does it change based on any taxpayer circumstance or action. es

The past year saw a resurgence of “head” or capitation taxes, which had long since fallen out of favor. Historically, head taxes were levied on individuals. What they lacked in equity, they made up for in administrative simplicity—a key consideration in medieval and early modern times. As other tax options emerged, head taxes fell out of favor (and, in some cases, into disrepute as they transformed into discriminatory poll taxes). A few states experimented with employment-based head taxes, imposed on the privilege of working, and assessed against either the employer or the employee—but these have been relatively rare. They exist, in different forms, in Colorado, Pennsylvania, Washington, and West Virginia, for instance, though frequently the levy was low (commonly $10 a year in Pennsylvania).

Then 2017 came along and suddenly head taxes were back in vogue, kicked off by a proposal for a $500 per-employee “business head tax” on large businesses in Seattle, Washington, home of Amazon and other major technology companies. Other cities with thriving tech sectors, like Cupertino (home of Apple) and Mountain View (home of Alphabet, the parent company of Google) in California, quickly expressed interest as well.[22]

Officials in these cities have argued that some technology companies impose a significant burden on local infrastructure but that their employees, who often live outside jurisdictional lines, have little exposure to local taxes. Business head taxes have been sold as a way to rectify this perceived wrong, often with the intention of raising money for expanded homelessness prevention services.

Unfortunately, business head taxes have the potential to be deeply counterproductive, which is why Seattle quickly reversed its decision to impose one. Taxes on job creation are rare—and for good reason.[23]

Even when the tax is limited to large employers, its impact can be vast. Not only do thresholds often capture low-margin businesses like supermarkets, but even small companies can take a big hit if major employers reduce their footprint. That’s particularly true of suppliers or other complementary companies, or smaller tech companies that locate in these high-cost areas to take advantage of the benefits of “tech agglomeration.”

Seattle dropped its head tax, but Mountain View, which proceeded more collaboratively, secured voter approval for a business head tax at the ballot in November. They are unlikely to be the last.

Reduced Taxation of Capital Stock and Tangible Personal Property

States have been slowly but steadily eliminating or reducing reliance on tangible personal property taxes (generally levied on business property like equipment and fixtures) for years.[24] Similarly, most states outside the Southeast have repealed their capital stock taxes, with Pennsylvania, Missouri, Rhode Island, and West Virginia the most recent to abandon them, while New York is in the midst of a multiyear phaseout and Mississippi began one this year.[25] There appears to be an emerging consensus that these taxes impede economic growth and are ill-suited to the modern economy.

Gross Receipts TaxA gross receipts tax, also known as a turnover tax, is applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like costs of goods sold and compensation. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and apply to business-to-business transactions in addition to final consumer purchases, leading to tax pyramiding. Consideration

Just over a decade ago, gross receipts taxes appeared to be on the verge of extinction, with the antiquated form of taxation persisting (at the state level) only in Delaware and Washington. In recent years, however, several states have turned to this highly nonneutral tax, chiefly as an alternative to volatile corporate income taxes. Ohio, Texas, and Nevada all adopted gross receipts taxes in the past decade, while several states–including California, Louisiana, Missouri, Oregon, West Virginia, and Wyoming–contemplated them over the past two years.

No new states adopted a gross receipts tax in 2018, but they remained under active consideration in Missouri, Oregon, and Wyoming. The circumstances behind this resurgence have not abated, and additional proposals can be expected in coming years.

Other Tax Issues

The estate taxAn estate tax is imposed on the net value of an individual’s taxable estate, after any exclusions or credits, at the time of death. The tax is paid by the estate itself before assets are distributed to heirs. continues to be repealed in a number of states, while revenue triggers continue to feature prominently in tax reform packages.

Declining Estate Tax Burdens

Until 2005, taxpayers received a federal credit for state inheritance and estate taxes paid, essentially rendering them (up to a certain limit) a way for states to raise additional revenue at no additional cost to their taxpayers. Since the phaseout of that provision, states have been moving away from estate and inheritance taxes, a trend that continues unabated. Before the credit’s repeal, all 50 states had an estate or inheritance taxAn inheritance tax is levied upon an individual’s estate at death or upon the assets transferred from the decedent’s estate to their heirs. Unlike estate taxes, inheritance tax exemptions apply to the size of the gift rather than the size of the estate. . Today, only 17 do, with two states–Delaware and New Jersey–repealing their estate taxes effective January 1, 2018. (New Jersey also imposes an inheritance tax. With estate tax repeal, Maryland is now the only state to impose both an inheritance and an estate tax.)[26]

As part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the federal exclusion amount was doubled to $11.2 million as of 2018, which in turn prompted higher exemption thresholds in a number of states which conform to federal provisions. There is a growing realization, moreover, that estate taxes can be counterproductive, driving high-net-worth retirees (who tend to be highly mobile) out of state, thus losing not only the potential estate tax revenue, but also years of income, sales, property, and other tax collections. There is every reason to expect that more states will follow in the footsteps of Delaware, New Jersey, and those that have already abandoned these taxes.

Continued Use of Revenue Triggers

After a lull in 2017, tax triggers reemerged in a big way in 2018, featuring in major tax reform packages in Iowa and Missouri. Triggers are an increasingly popular mechanism for phasing in tax reform measures subject to revenue availability. When designed correctly, triggers limit the volatility and unpredictability associated with changes to the tax code and can be an important part of the toolkit for states seeking to balance the economic impetus for tax reform with a governmental interest in revenue predictability.

In Iowa, the past year saw the adoption of a significant tax reform package which will ultimately lower individual and corporate income tax rates, repeal the alternative minimum tax, modestly broaden the sales tax base, and phase out an outmoded policy of federal deductibility. In Missouri, rate cuts were paired with the elimination of some exemptions and a narrowing of federal deductibility. Iowa is using triggers to phase in a number of its reforms, including the rate reductions, while Missouri adopts rate cuts in tandem with revenue-raising reforms, then resumes a previously-adopted schedule of tax triggers to implement further rate reductions subject to revenue availability.

Over the past decade, 12 states and the District of Columbia have turned to tax triggers to implement contingent tax rate reductions or other reforms. It is a trend that can be expected to continue, as well-constructed triggers can enhance stability and aid states in implementing tax policy changes in a fiscally responsible manner.[27]

Conclusion

The year 2018 was an eventful one in the realm of state taxation, but there is little to suggest that activity will slacken in the year to come. State interest in taxing remote sales and legalizing and taxing both sports betting and marijuana should continue unabated. While most states now conform, at least in part, to the new federal tax law, many important considerations–from how to handle the international provisions to what to do with the revenue–were postponed and will continue to dominate the tax conversation in 2019 and beyond.

Long-term trends, like the declining importance of corporate income taxes and starker economic implications of retaining an estate tax, will continue to figure into states’ tax considerations, while new mechanisms like tax triggers can be expected to feature prominently in future tax reforms. In recent years, moreover, tax plans have increasingly been comprehensive, reforming multiple taxes at once rather than being limited to a single tax. Often previously considered too daunting, comprehensive reform is increasingly viewed as more practical, as it allows reforms to be balanced against each other. In 2018, Iowa became the latest state to adopt a comprehensive reform package, but with several other states already gearing up for significant reform pushes, it will not be the last.

George Santayana’s maxim that those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it is widely cited. Two sentences prior, he wrote, “Progress, far from consisting in change, depends on retentiveness.”[28] Whatever progress policymakers wish to make on tax policy in 2019, they would do well to begin by internalizing the lessons to be gleaned from other states’ efforts in recent years.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeNotes

[1] See generally Jared Walczak, “Tax Reform Moves to the States: State Revenue Implications and Reform Opportunities Following Federal Tax Reform,” Jan. 31, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/state-conformity-federal-tax-reform/.

[2] In some cases, the implications cannot be wholly avoided by failing to conform to the IRC post-TCJA. For instance, Virginia expressly decouples from the provisions of the new federal law, but it requires a filers’ choice to take the federal standard deduction to be replicated on their state tax forms. Because many more filers will benefit from taking the federal standard deduction, Virginia can expect additional revenue as these filers must now take Virginia’s standard deduction even though, all else being equal, they would benefit from being able to itemize at the state level.

[3] State statutes; Bloomberg Tax; Tax Foundation research.

[4] See generally Jared Walczak, “State Strategies to Preserve SALT Deductions for High-Income Taxpayers: Will They Work?” Tax Foundation, Jan. 5, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/state-strategies-preserve-state-and-local-tax-deduction/.

[5] U.S. Department of the Treasury, REG-112176-18, “Contributions in Exchange for State or Local Tax CreditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. s,” 83 Fed. Reg. 43563 (Aug. 27, 2018).

[6] Scott Greenberg, “Pass-Through Businesses: Data and Policy,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 17, 2017, 7, https://taxfoundation.org/pass-through-businesses-data-and-policy/.

[7] Jared Walczak, “State Tax Changes That Took Effect on January 1, 2018,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 2, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/state-tax-changes-took-effect-january-1-2018/; Tax Foundation research.

[8] Ben Strachman and Scott Drenkard, “Business and Individual Taxpayers See No Reprieve in New Jersey Tax Package,” Tax Foundation, July 3, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/individual-income-tax-corporate-tax-hike-new-jersey/.

[9] U.S. Census Bureau, “Quarterly Retail E-Commerce Sales, 3rd Quarter 2018,” CB18-173, Nov. 19, 2018, https://www.census.gov/retail/mrts/www/data/pdf/ec_current.pdf.

[10] South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc., 585 U.S. ___ (2018).

[11] Joseph Bishop-Henchman, Hannah Walker, and Denise Garb, “Post-Wayfair Options for States,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 29, 2018, 6, https://taxfoundation.org/post-wayfair-options-for-states/.

[12] Id.

[13] Business inputs are excluded to avoid what is known as tax pyramidingTax pyramiding occurs when the same final good or service is taxed multiple times along the production process. This yields vastly different effective tax rates depending on the length of the supply chain and disproportionately harms low-margin firms. Gross receipts taxes are a prime example of tax pyramiding in action. , where the final price includes the sales tax embedded at multiple points across the production process. In an optimal sales tax, only final consumption is subject to taxation.

[14] Joseph Bishop-Henchman, Jared Walczak, and Katherine Loughead, “Results of 2018 State and Local Tax Ballot Initiatives,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 6, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/2018-state-tax-ballot-results/.

[15] Brent Johnson, “The Story of When N.J. Almost Legalized Sports Betting in 1993,” NJAdvanceMedia.com, March 15, 2015, https://www.nj.com/politics/index.ssf/2015/03/the_story_of_njs_missed_opportunity_on_sports_bett.html.

[16] Ryan Prete, “States Cash in on Sports Betting Taxes, More Expected to Play,” Bloomberg Tax, Aug. 1, 2018, https://www.bna.com/states-cash-sports-n73014481301/.

[17] Howard Gleckman, “6 Reasons Why States Shouldn’t Be Counting Their Sports Betting Tax Revenue Yet,” Forbes, May 16, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/howardgleckman/2018/05/16/six-reasons-why-states-shouldnt-be-counting-their-sports-betting-tax-revenue-yet/.

[18] Ryan Rodenberg, “State-by-State Sports Betting Bill Tracker,” ESPN.com, Nov. 26, 2018, http://www.espn.com/chalk/story/_/id/19740480/gambling-sports-betting-bill-tracker-all-50-states.

[19] Samuel Stebbins, Grant Suneson, and John Harrington, “Pot Initiatives: Predicting the Next 15 States to Legalize Marijuana,” USA TODAY, Nov. 14, 2017, https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2017/11/14/pot-initiatives-predicting-next-15-states-legalize-marijuana/860502001/.

[20] Joseph Bishop-Henchman, Jared Walczak, and Katherine Loughead, “Results of 2018 State and Local Tax Ballot Initiatives.”

[21] Joseph Bishop-Henchman and Morgan Scarboro, “Marijuana Legalization and Taxes: Lessons for Other States from Colorado and Washington,” Tax Foundation, May 12, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/marijuana-taxes-lessons-colorado-washington/.

[22] Jared Walczak, “Business Head Taxes Take Aim at Having ‘Too Many Good Jobs,’” Tax Foundation, May 22, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/business-head-taxes-take-aim-many-good-jobs/.

[23] Jared Walczak, “Seattle Council Votes Overwhelmingly to Repeal New Business Head Tax,” Tax Foundation, June 12, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/seattle-city-council-votes-overwhelmingly-repeal-new-business-head-tax-2/.

[24] Joyce Errecart, Ed Gerrish, and Scott Drenkard, “States Moving Away from Taxes on Tangible Personal Property,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 4, 2012, https://taxfoundation.org/states-moving-away-taxes-tangible-personal-property/.

[25] Morgan Scarboro, “Does Your State Levy a Capital Stock Tax?” Tax Foundation, Oct. 5, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/state-levy-capital-stock-tax/.

[26] Jared Walczak, “State Inheritance and Estate Taxes: Rates, Economic Implications, and the Return of Interstate Competition,” Tax Foundation, July 17, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/state-inheritance-estate-taxes-economic-implications/.

[27] For a consideration of the elements of tax trigger design, see Jared Walczak, “Designing Tax Triggers: Lessons from the States,” Tax Foundation, Sept. 7, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/designing-tax-triggers-lessons-states/.

[28] George Santayana, The Life of Reason: The Phases of Human Progress (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1906), Vol, 1, Ch. XII.

Share