Update 11/26/18:

California: Officials are planning an early 2019 collections start date.

Colorado: On September 11, 2018, the Department of Revenue announced they would begin collection on December 1, 2018, by administrative rule. The rule applies only prospectively and excludes retailers whose sales are less than $100,000 or 200 transactions annually. The state Department of Revenue will be the collection point for all local sales taxes, but the state has not joined the Streamlined agreement.

Idaho: Idaho began enforcing a click-through nexus law (collection requirement if you provide referral commissions to in-state residents) on July 1, 2018.

Nevada: Nevada Department of Taxation adopted a rule effective October 1, 2018 requiring collection by any seller with more than $100,000 in sales or 200 transactions in the previous or current calendar year. Collection begins November 1, 2018. Nevada is a Streamlined member.

New Jersey: Effective date changed from October 1, 2018 to November 1, 2018 following a bill veto and subsequent legislative action.

South Dakota: Collection began November 1, 2018 following the end of court proceedings.

Texas: Texas Comptroller’s office says they will seek legislation in the January 2019 legislative session to begin collection. Collection will not be retroactive. Effective date will be set in the legislation.

West Virginia: Collection begins January 1, 2019 following an administrative rule announcement. Collection is not required by sellers with less than $100,000 in sales or fewer than 200 transactions during the previous calendar year. The state is a Streamlined member.

Key Findings

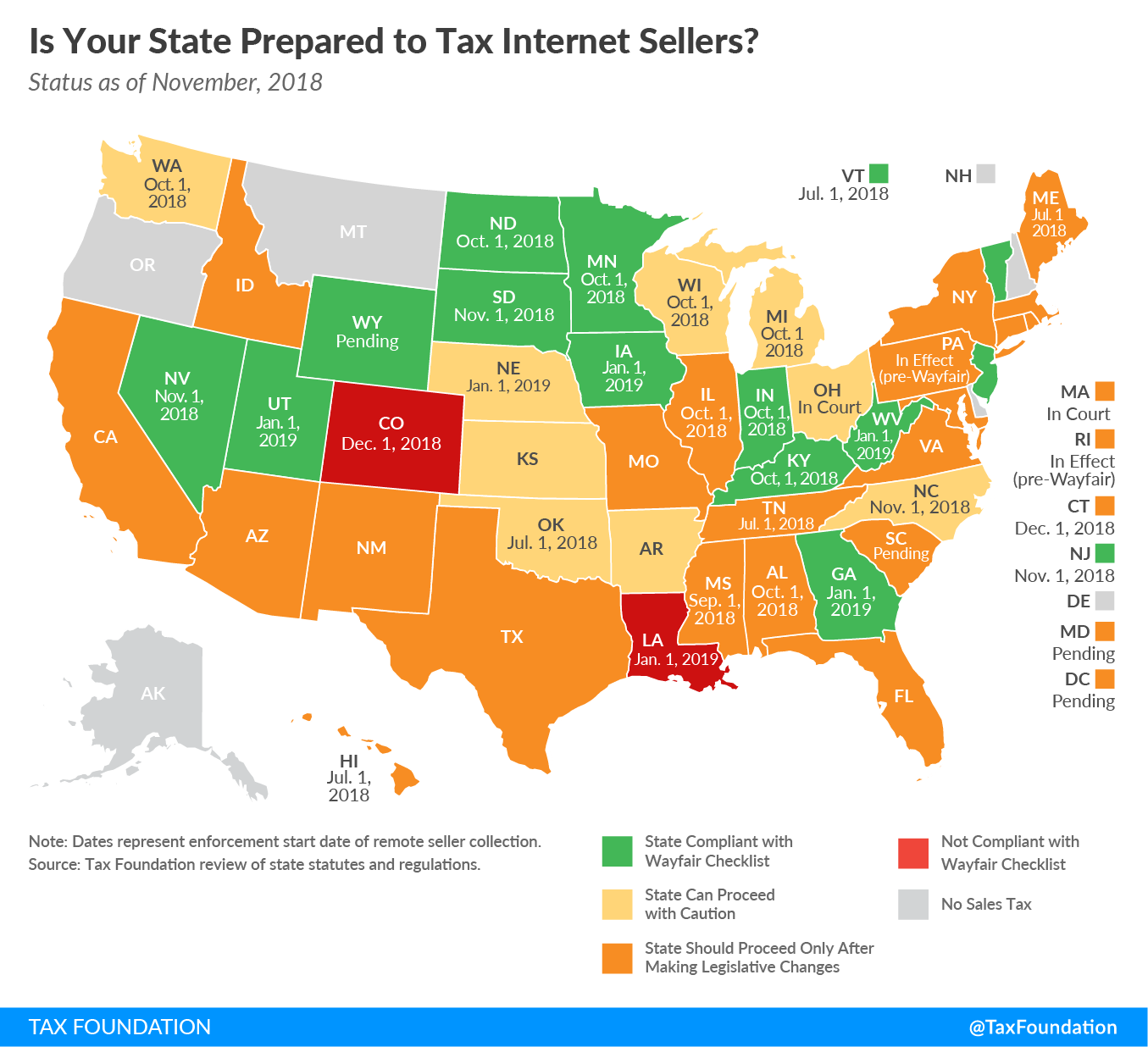

- The U.S. Supreme Court in South Dakota v. WayfairSouth Dakota v. Wayfair was a 2018 U.S. Supreme Court decision eliminating the requirement that a seller have physical presence in the taxing state to be able to collect and remit sales taxes to that state. It expanded states’ abilities to collect sales taxes from e-commerce and other remote transactions. this year ruled that a state may require collection of sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. by out-of-state internet retailers who sell into the state (“remote sellers”), so long as the law does not discriminate against or place excessive burdens on those engaging in interstate commerce.

- The Court strongly suggested that a law that follows what we call “the Wayfair checklist” would be constitutional. States can satisfy this checklist by adopting a de minimis threshold, explicitly rejecting retroactive enforcement, and adhering to uniformity and simplification rules in the Streamlined Sales and Use TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. Agreement (SSUTA).

- Policy choices for state officials include whether to adopt a more generous de minimis threshold, when the qualifying period for the threshold should be, what date enforcement should start, whether to include local taxes, and how to use the revenue.

- Thirty-two states are acting to pass laws or regulations to require sales tax collection by remote sellers now or in the immediate future:

- Preexisting prior to Wayfair: Pennsylvania & Rhode Island (both give retailers a choice between collecting tax or complying with notice-and-reporting laws)

- July 1, 2018: Colorado (notice-and-reporting only), Hawaii, Maine, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Vermont

- September 1, 2018: Mississippi

- October 1, 2018: Alabama, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, North Dakota, Washington, Wisconsin

- November 1, 2018: North Carolina

- December 1, 2018: Connecticut

- January 1, 2019: Georgia, Iowa, Louisiana, Nebraska, Utah

- Not yet formalized: Maryland, Nevada, South Carolina, Wyoming

- In litigation: Massachusetts, Ohio, South Dakota

- States we identify as “yellow light” and “red light” states, particularly those that are not SSUTA members, should undertake improvements to their sales tax systems and consider higher de minimis thresholds to minimize the risk of legal challenge to future remote seller tax collection. At minimum states should allow sellers to register with SSUTA rather than requiring state-by-state registrations, allow SSUTA service providers to work with their state, restrict multistate audits, and provide taxability, exemption, rate, and boundary data for download on their websites.

Introduction

On June 21, 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in South Dakota v. Wayfair that South Dakota can require collection of its sales tax on sales to its residents by out-of-state internet retailers.[2] The 5 to 4 decision overruled two earlier precedents, National Bellas Hess, Inc. v. Illinois Department of Revenue (1967) and Quill Corp. v. North Dakota (1992), which had both held that only businesses with a physical presence in a state can be required to collect that state’s sales tax. The new rule, articulated in Wayfair, is that a state sales tax can be constitutionally collected so long as it does not discriminate against or place excessive burdens on those engaging in interstate commerce.

Since the decision, states have begun considering actions that they might need to take to collect sales tax on internet transactions while adhering to the Wayfair decision. The Court stopped short of upholding South Dakota’s collection of remote sales taxes as constitutional but gave several reasons why the state’s law in particular and its tax compliance system in general would not be a burden on interstate commerce. This report reviews the Wayfair decision and evaluates existing state laws to determine what further action each state may need to take.

South Dakota’s Law

South Dakota S.B. 106 was the law contested in Wayfair. It requires sales tax collection by out-of-state sellers if they have a minimum of $100,000 in sales or 200 transactions per year in the state. This de minimis threshold, or safe harbor, has the effect of excluding those sellers with incidental sales into the state and where establishing collection mechanisms might outstrip the business’s incremental revenue from selling into South Dakota. South Dakota’s statute also has a provision barring retroactive collection. South Dakota passed the law with unanimous votes and it was signed into law on March 22, 2016, to take effect on May 1, 2016.[3]

South Dakota was well-chosen as the state to bring the challenge to Quill, for four main reasons. First, the state is a full member of the Streamlined Sales Tax and Use Agreement (SSUTA), a multistate organization that works to increase uniformity and reduce complexity in sales tax collection. Second, South Dakota taxes nearly all goods and services under its sales tax, avoiding definitional and administrative problems encountered by other states in distinguishing among items. Third, while there are local sales taxes in South Dakota, the state keeps it simple in requiring them to adhere to the state base of transactions and only at uniform rates. Fourth, South Dakota has no state individual income or corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. ; sales and property taxes are essentially its only taxes and make up three-quarters of total South Dakota state and local tax revenue.

The Wayfair Decision

Justice Anthony Kennedy delivered the opinion for the five-justice majority. The opinion first recited the history of the dormant Commerce Clause, a doctrine that prevents states from discriminating against interstate commerce or placing undue burdens upon interstate commerce. The Court noted that the 1970 Complete Auto case[4] formulated a four-part test to evaluate state laws under the dormant Commerce Clause doctrine, with one of those parts being “substantial nexus,” a sufficient connection between the state and the taxpayer.

The opinion then gives three reasons for deeming Quill flawed. First, physical presence is not a necessary interpretation of substantial nexus from Complete Auto. Kennedy writes that “[t]he physical presence rule is a poor proxy for the compliance costs faced by companies that do business in multiple States,” comparing a company with a salesperson in each state that must therefore collect tax with a company with 500 people in one central location and a website accessible in every state that need only collect in one state. Second, the Quill rule creates market distortions between brick-and-mortar and online retailers–“a judicially created tax shelter,” in the Court’s words–and an incentive to avoid physical presence in multiple states purely for tax avoidance reasons.[5] Third, the physical presence standard is arbitrary and formalistic, rather than looking at the substance of a law’s compliance burdens or discriminatory effect.

The Court acknowledged substantial reliance on its earlier decisions, conducting a stare decisis analysis. Against this reliance the Court listed the need to correct an error depriving states from exercising lawful powers, the strong growth of e-commerce and consequent growth in the states’ revenue shortfalls from being unable to tax online sellers, and the variety of state laws working to “embroil courts in technical and arbitrary disputes about what counts as physical presence.”[6]

The Court also acknowledged burdens associated with tax compliance but expressed hope that software and other systems will be able to reduce these costs. The Court noted that South Dakota, as a SSUTA member, had done much to make compliance easier. If not, the Court stated, Congress could act to address these problems through legislation. Finally, small sellers seeking relief from future state laws that impose excessive burdens on them “may still do so under other theories.”[7]

The Court then stated that “the physical presence rule of Quill is unsound and incorrect,” and overruled Quill and Bellas Hess. The Court concludes that the statute’s standard of $100,000 in sales or 200 transactions can only be met if “the seller availed itself of the substantial privilege of carrying on business in South Dakota. And respondents are large, national companies that undoubtedly maintain an extensive virtual presence. Thus, the substantial nexus requirement of Complete Auto is satisfied in this case.”

The decision did not end there, and experts since have debated whether what follows is binding or not. The Court remands the South Dakota law for further consideration. But before concluding the decision, the Court offered a checklist of why the South Dakota law would likely be constitutional:

That said, South Dakota’s tax system includes several features that appear designed to prevent discrimination against or undue burdens upon interstate commerce. First, the Act applies a safe harbor to those who transact only limited business in South Dakota. Second, the Act ensures that no obligation to remit the sales tax may be applied retroactively. S. B. 106, §5. Third, South Dakota is one of more than 20 States that have adopted the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement. This system standardizes taxes to reduce administrative and compliance costs: It requires a single, state level tax administration, uniform definitions of products and services, simplified tax rate structures, and other uniform rules. It also provides sellers access to sales tax administration software paid for by the State. Sellers who choose to use such software are immune from audit liability.

Two justices wrote separate concurring opinions while joining the majority opinion. Justice Clarence Thomas concurred to write that he should have joined the Quill dissent in 1992. Justice Neil Gorsuch concurred, joining the majority in full and adding that he questions Commerce Clause doctrine.

Four justices dissented, in an opinion authored by Chief Justice John Roberts. The dissent agreed that “Bellas Hess was wrongly decided, for many of the reasons given by the Court,” but urged that any change to the physical presence rule be undertaken by Congress. Unlike in other contexts where only the Supreme Court can reverse a previous decision, Commerce Clause decisions by the Court can be changed by Congress.[8] Roberts also took issue with the Court’s sense of urgency, pointing out that states are already able to collect the vast majority of potential online sales tax revenue. He worried that the burden of getting it wrong will fall squarely on small sellers, another reason for Congress to draw where the line should be instead of the Court.

The Wayfair Checklist

The Court provided a checklist of factors present in South Dakota law that strongly suggested why it would be constitutional under this standard:

- Safe harbor: Exclude “those who transact only limited business” in the state. (South Dakota’s is $100,000 in sales or 200 transactions.)

- No retroactive collection.

- Single state-level administration of all sales taxes in the state.

- Uniform definitions of products and services.

- Simplified tax rate structure. (South Dakota requires the same tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. between state and local sales tax, has only three sales tax rates, and limited exemptions from the tax.)

- Software: access to sales tax administration software provided by the state.

- Immunity: sellers who use the software are not liable for errors derived from relying on it.

In South Dakota, the first two items on the checklist were met through S.B. 106, the enabling law directly challenged in Wayfair. The other five items were met through other provisions in state law relating to South Dakota’s adherence to SSUTA.

Policy Choices for Legislators

Legislators may make several policy choices when complying with the Wayfair checklist:

- Adopt the same threshold as South Dakota ($100,000 in sales or 200 transactions) or a more generous one to account for larger population size or larger economy. A state could also drop the number of transactions requirement to avoid impacting a seller with many small transactions.

- Decide when the threshold period is measured. South Dakota’s law looked at the previous calendar year and current calendar year, with collection commencing only after the threshold was met. Other states have considered continuing most-recent-12-month periods, or 12 months ending on the most recent quarter. Small retailers, whom this provision is meant to protect, benefit from clear and easy-to-track rules in this regard, which mitigate in favor of calendar periods rather than roving periods.

- Setting an enforcement start date. States should give retailers enough notice before collection must begin. The National Conference of State Legislatures has recommended that states begin collection on a calendar quarter and consider waiting until at least January 1, 2019[9].

- Consider repealing click-through nexus and notice-and-reporting laws. If a seller is pressured to collect through those laws but would not meet the de minimis threshold, the enforcement of those laws could be a Due Process Clause or Commerce Clause violation.

- Decide how to collect local sales taxes. This may not be advisable in states that do not provide lookup software and unified collection under SSUTA. States with a large number of local sales tax jurisdictions might consider imposing a “flat” local sales tax on internet sales, as Alabama has done, if simplification is not possible. However, a flat sales tax higher than the lowest sales tax charged anywhere in the state is probably unconstitutional.[10]

- Decide use of the revenue. The Government Accountability Office estimated additional state and local government revenue from remote seller tax collection of between $8 billion and $13 billion per year[11]. Several states plan to use internet sales tax revenue for tax reductions:

- Arkansas law currently requires remote seller revenue above $70 million per year be used to reduce the 4.5 percent bracket of its individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. . The state’s Tax Reform Task Force is developing more detailed tax reform proposals that include tax reductions offset by internet sales taxAn internet sales tax is a sales and use tax collected and remitted on remote sales, many done online. In 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that states could impose such obligations on sellers lacking physical presence in the state, vastly expanding the reach of these collection and remittance requirements. revenue[12].

- Georgia law envisions[13] an individual income tax rate reduction, from 5.75 percent to 5.5 percent, contingent on revenue performance and legislative action. The reduction is more likely to occur due to additional internet sales tax revenue.

- Iowa passed a major tax reform[14], reducing income and corporate tax rates and including additional internet sales tax revenue.

- Kentucky passed a major tax overhaul[15], reducing income and corporate tax rates and including additional internet sales tax revenue.

- South Dakota plans[16] on reducing its overall state sales tax rate in stages, from the current 4.5 percent to 4 percent.

- Utah law eliminates the final remnant[17] of its double sales tax on manufacturing machinery with internet sales tax revenue.

- Wisconsin is considering[18] using the additional revenue for income tax reductions[19].

Green Light: Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Minnesota, New Jersey, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, and Wyoming Can Proceed

Eleven states have adopted all seven provisions of the Wayfair checklist, through SSUTA membership and enabling legislation with de minimis thresholds and retroactive bans similar to or better than South Dakota’s law. The collection of sales tax on internet transactions by these states is therefore permissible under current court rulings.

- Georgia law[20] adopts a $250,000 or 200-transaction threshold, in the previous or current calendar year, with an effective date of January 1, 2019. The state is a full member of SSUTA.

- Indiana law[21] adopts a $100,000 or 200-transaction threshold, in the previous or current calendar year, effective prospectively after all appeals have concluded. The state is a full member of SSUTA. The Indiana Department of Revenue has set a collection start date[22] of October 1, 2018, and has set up a FAQ page[23].

- Iowa law[24] adopts a $100,000 or 200-transaction threshold, in the previous or current calendar year, with an effective date of January 1, 2019. The state is a full member of SSUTA. The Iowa Department of Revenue has set up a FAQ page[25].

- Kentucky law[26] adopts a $100,000 or 200-transaction threshold, in the previous or current calendar year, effective prospectively. The state is a full member of SSUTA. The Kentucky Department of Revenue has set a collection start date of October 1, 2018, and has set up a FAQ page[27].

- Minnesota Department of Revenue has issued a regulation enforcing a statute[46] to require sales tax collection by internet sellers with sales of at least 10 that total more than $100,000, or 100 more sales shipped to Minnesota, in any period of 12 consecutive months, effective October 1, 2018.

- New Jersey law[28] adopts a $100,000 or 200-transaction threshold, in the previous or current calendar year, effective prospectively. The state is a full member of SSUTA. The New Jersey Division of Taxation has set a collection start date[29] of October 1, 2018, and has set up a FAQ page.

- North Dakota law[30] adopts a $100,000 or 200-transaction threshold, in the previous or current calendar year. The state is a full member of SSUTA. The State Tax Commissioner has set a collection start date[31] of October 1, 2018, and has set up a FAQ page[32].

- South Dakota law[33] adopts a $100,000 or 200-transaction threshold, in the previous or current calendar year, effective prospectively after pendency of appeals conclude. The state is a full member of SSUTA. The South Dakota Department of Revenue has set up a FAQ page[34].

- Utah law[35] adopts a $100,000 or 200-transaction threshold, in the previous or current calendar year, with an effective date of January 1, 2019. The state is a full member of SSUTA. The Utah State Tax Commission has set up a FAQ page[36].

- Vermont law[37] adopts a $100,000 or 200-transaction threshold, during any 12-month period preceding the current month, with an effective date of July 1, 2018. The state is a full member of SSUTA. The state had recently stepped up[38] its enforcement of use tax by sending letters to consumers. The Vermont Department of Taxes has set up a FAQ page[39].

- Wyoming law[40] adopts a $100,000 or 200-transaction threshold, in the previous or current calendar year, effective prospectively. The state is a full member of SSUTA. The Wyoming Department of Revenue has not yet set a collection start date[41], but October 1, 2018 has been mentioned.

Flashing Yellow Light: Arkansas, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, Nevada, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Washington, West Virginia, and Wisconsin Can Proceed with Caution

Twelve states have completed items 3 through 7 of the Wayfair checklist as a result of SSUTA membership. They have not yet passed enabling legislation to make them compliant with items 1 and 2 of the Wayfair checklist. If they wish to pursue collection of sales tax on internet transactions, these states should pass enabling legislation with a de minimis threshold and a ban on retroactive collection similar to or more generous than the South Dakota standards. Some states may assert authority to collect through regulatory action, but to be on firm legal ground the state should pass enabling legislation as soon as practicable.

- Arkansas has provided an FAQ page[42] on remote sales. A Tax Reform Task Force has recommended adoption of legislation[43] similar to South Dakota’s in the near future.

- Michigan Department of Treasury has issued a regulation[44] to require sales tax collection by internet sellers with sales of at least $100,000 or more than 200 transactions in the previous calendar year, effective October 1, 2018. The Department did not cite a statutory basis for its regulation, although a prior regulation[45] cited the state’s very broad (and perhaps unconstitutionally broad) nexus statute. Consequently, the regulation’s enforcement could face legal challenge, which can be avoided through enactment of an enabling statute similar to South Dakota’s.

- Nebraska While the Nebraska Department of Revenue issued a statement[47] reiterating current Nebraska law which only extends to sellers with in-state property, in-state sellers, sales via in-state broadcast television, or sales into the state of banking/marketing/repair/installation services by mail, the Department emailed the Tax Foundation on August 31 to indicate they interpret that statute as applying to all remote sellers who meet a threshold of $100,000 or more than 200 transactions annually, effective January 1, 2019. The Department indicated in its statement that it may seek legislation in the 2019 session.

- Nevada Department of Taxation has proposed a draft regulation[48] to require sales tax collection by internet sellers with sales of at least $100,000 or more than 200 transactions in the current or previous calendar year, to be enforced prospectively. The Department cited state law authorizing collection of sales tax up to the limits of the United States Constitution. The regulation will be considered for adoption[49] on September 13, 2018, with implementation as early as October or November 2018. The state should consider enactment of a statute codifying these provisions.

- North Carolina Department of Revenue has issued a directive[50] to require sales tax collection by internet sellers with sales of at least $100,000 or more than 200 transactions in the previous or current calendar year, effective November 1, 2018, or 60 days after the seller meets the threshold, whichever is later. The Department cited the state’s very broad (and perhaps unconstitutionally broad) nexus statute. Consequently, the regulation’s enforcement could face legal challenge, which can be avoided through enactment of an enabling statute similar to South Dakota’s.

- Ohio Department of Taxation tweeted[51] that legislative action would be required before remote sellers would be required to collect tax. However, Ohio has a statute[52] requiring tax collection by internet retailers who sell more than $500,000 into the state and place software or an app on computers or phones in Ohio. The law is currently being challenged by the American Catalog Mailers Association, and given that the law relies on a physical presence justification that no longer is good law, the challenge may succeed.

- Oklahoma law[53] includes a notice-and-reporting requirement for retailers with more than $10,000 in sales in the state in the preceding 12 calendar months, and retailers must either collect the tax or comply with the notice-and-reporting provision, effective July 1, 2018.

- Rhode Island law[54] adopts a $100,000 or 200-transaction threshold but gives retailers a choice of collecting or complying with the state’s notice-and-reporting law. That legislation went into effect on August 17, 2017. The state should consider disavowing retroactive enforcement for retailers who did not register prior to issuance of the Department of Revenue Division of Taxation’s revised post-Wayfair statement[55] on July 20, 2018.

- Washington Department of Revenue announced on August 3, 2018[56] that retailers with $100,000 in gross retail sales or 200 transactions in the current or previous year must collect sales tax, effective October 1, 2018. The Department did not cite a statutory basis for its announcement. This new requirement is in addition to a law that went into effect July 7, 2017[57] that includes a notice-and-reporting requirement for retailers with more than $10,000 in sales in the state, and retailers must either collect the tax or comply with the notice-and-reporting provision. There is also a click-through nexus provision for referrers with more than $267,000 in sales in the state. Remote retailers with $267,000 in gross receipts in the state are also deemed to have nexus[58] for the state’s Business & Occupation gross receipts taxGross receipts taxes are applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like compensation, costs of goods sold, and overhead costs. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and applies to transactions at every stage of the production process, leading to tax pyramiding. . The Department has posted a FAQ page[59]. The state should consider enactment of a statute codifying these provisions and rescinding any duplicative or superseded portions of the 2017 law. The state should also consider increasing the de minimis threshold for its marketplace law (discussed below) above the very minimal $10,000.

- Wisconsin Department of Revenue has announced[60] that it will require sales tax collection by internet sellers with sales of at least $100,000 or more than 200 transactions annually, effective October 1, 2018. The state should consider enactment of a statute codifying these provisions.

Steady Yellow Light: Alabama, Arizona, California, Connecticut, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Missouri, New Mexico, New York, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and the District of Columbia Should Only Proceed After Making Legislative Changes

The remaining states have not completed several items on the Wayfair checklist, in large part due to their non-membership of SSUTA. Without action to adopt uniform definitions and simplify their sales tax systems, requiring collection from internet sellers will be under a cloud of legal uncertainty. At minimum states should allow sellers to register with SSUTA rather than requiring state-by-state registrations, limit multistate audits, allow SSUTA service providers to work with their state, and provide taxability, exemption, rate, and boundary data for download on their websites.

Several of these states have passed legislation or adopted regulations relating to taxation of internet sales:

- Alabama has a revenue rule[61] adopting a $250,000 threshold but no transaction minimum. The Alabama Department of Revenue has set a collection start date[62] of October 1, 2018. The state is not a member of SSUTA, and does not adhere to common definitions, does not provide base/rate lookup software or immunity from errors resulting from reliance on software, but has established a portal to pay all state and local sales taxes[63] and does offer the option[64] of collecting a flat 8 percent tax in lieu of the multiple sales taxes imposed by the state’s taxing jurisdictions. While the state should pursue SSUTA membership, the 8 percent flat taxAn income tax is referred to as a “flat tax” when all taxable income is subject to the same tax rate, regardless of income level or assets. option does somewhat reduce the burden on interstate sellers and should not be removed.

- California officials are considering a higher threshold[65] of $500,000, although a draft document[66] accidentally placed on the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration’s public website would have set[67] a $100,000 or 200-transaction threshold.

- Connecticut law[68] adopts a $250,000 and 200-transaction threshold (during the 12-month period ending September 30, 2018), with an effective date of December 1, 2018. The preexisting click-through nexus law is amended to adjust the de minimis threshold from a very low $2,000 to $250,000 as well. The state also has[69] a notice-and-reporting law that requires quarterly statements sent to each seller beginning July 1, 2019, and an annual notice to the Commissioner of Revenue Services starting January 31, 2020. The state is not a member of SSUTA, does not adhere to common definitions, and does not provide base/rate lookup software or immunity from errors resulting from reliance on software, but does have centralized collection of sales tax. (Connecticut has no local sales taxes.) While the state should pursue SSUTA membership, the lack of local sales tax jurisdictions does somewhat reduce the burden on interstate sellers.

- Hawaii law[70] adopts a $100,000 or 200-transaction threshold (during the previous calendar year) for its sales tax (called the General Excise TaxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. ), effective prospectively. The Hawaii Department of Taxation announced a collection effective date[71] of July 1, 2018, with the first filing due August 20, 2018. The Department has stated that those who met the $100,000 or 200-transaction threshold in 2017 or 2018 will not be required to remit tax for the period prior to July 1, 2018, but must begin filing thereafter. The state is not a member of SSUTA, does not adhere to common definitions, and does not provide base/rate lookup software or immunity from errors resulting from reliance on software, but does have centralized collection of sales tax. (Hawaii has only one local sales tax jurisdiction, Oahu County.) The state also taxes nearly all goods and services under its tax, unlike most other states, thereby avoiding base calculation and definition problems. While the state should pursue SSUTA membership, having only one sales tax jurisdiction and broadly taxing all goods and services does somewhat reduce the burden on interstate sellers.

- Idaho has not moved to apply the Wayfair ruling but is enforcing its click-through nexus law[72].

- Illinois law[73] adopts a $100,000 or 200-transaction threshold (determined at the end of each March, June, September, and December for the previous 12 months), with an effective date of October 1, 2018. The state is not a member of SSUTA, does not adhere to common definitions, and does not provide base/rate lookup software (other than a website), but does have centralized collection of sales tax for its 563 local sales tax jurisdictions[74]. State law waives[75] penalties assessed based on erroneous information provided by the state, and purchasers can pursue refunds directly from the state[76] instead of the seller. There are different sales tax rates[77] on general merchandise, food and drugs, and vehicles. The state should pursue SSUTA membership, because the significant complexity associated with collecting the state and local sales tax places an undue burden on interstate sellers.

- Maine law[78] adopts a $100,000 or 200-transaction threshold (in the previous or current calendar years), and Maine Revenue Services began enforcing collection[79] from July 1, 2018. The state is not a member of SSUTA, does not adhere to common definitions, and does not provide base/rate lookup software or immunity from errors resulting from reliance on software (aside from a website), but does have centralized collection of sales tax. (Maine has no local sales taxes.) While the state should pursue SSUTA membership, the lack of local sales tax jurisdictions does somewhat reduce the burden on interstate sellers.

- Massachusetts has adopted a regulation[80] defining the placement of website “cookies” on in-state computers as physical presence and requiring retailers who do so to collect sales tax, if the retailer had at least $500,000 in Massachusetts sales and 100 or more transactions in the previous calendar year, and excluded retailers whose only connection with the state is that a website can be accessed from within the state. The regulation is being challenged[81] by Crutchfield Corporation; an earlier version of the regulation had been withdrawn[82] under legal scrutiny. The state is not a member of SSUTA, does not adhere to common definitions, and does not provide base/rate lookup software or immunity from errors resulting from reliance on software, but does have centralized collection of sales tax. (Massachusetts has no local sales taxes.) While the state should pursue SSUTA membership, the lack of local sales tax jurisdictions does somewhat reduce the burden on interstate sellers.

- Mississippi has adopted a regulation[83] setting a $250,000 threshold (in the previous 12 months) but no transaction minimum, effective prospectively from December 1, 2017. The Mississippi Department of Revenue has issued a statement[84] setting the beginning of enforcement with sales on or after September 1, 2018, and urged remote sellers to register by August 31, 2018. The state is not a member of SSUTA, does not adhere to common definitions, and does not provide base/rate lookup software or immunity from errors resulting from reliance on software (aside from a website), but does have centralized collection of sales tax. (Mississippi has no local sales taxes.) While the state should pursue SSUTA membership, the lack of local sales tax jurisdictions does somewhat reduce the burden on interstate sellers.

- Pennsylvania law[85], Act 43, adopts a $10,000 threshold (in the previous 12 months) but no transaction minimum, effective prospectively from March 1, 2018, and each June 1 thereafter beginning June 1, 2019. Prior to the Wayfair decision, the Pennsylvania Department of Revenue had clarified that sellers must choose[86] one or two options: collect, or comply with the state’s notice-and-reporting law. The state is not a member of SSUTA, does not adhere to common definitions, and does not provide base/rate lookup software or immunity from errors resulting from reliance on software, but does have centralized collection of sales tax (Pennsylvania has only two local sales tax jurisdictions, Philadelphia and Allegheny County) and a website list of taxable items[87]. The constitutionality of Pennsylvania’s Act 43 is murky, and aggressive enforcement of internet retailers under its provisions could result in a successful legal challenge. The state should pursue SSUTA membership and, if it wishes to collect tax from internet retailers, revise enabling legislation similar to or more generous than South Dakota’s.

- Tennessee has adopted a regulation[88] setting a $500,000 threshold (in the previous 12 months) but no transaction minimum, effective prospectively from July 1, 2017. Enforcement is on hold pending disposition of a legal challenge[89] by the American Catalog Association, and collection is unlikely to begin before early 2019. The state is not a full member of SSUTA, but has enacted legislation to become a full member[90] as of July 1, 2019. Until then, the state adheres to most common definitions, and provides base/rate lookup software. It also provides centralized collection of sales tax (Tennessee has 298 local sales tax jurisdictions), but until July 1, 2019, tax bases can differ between state and local jurisdictions. Based on the current state of Tennessee law, the $500,000 threshold regulation may not survive legal challenge. The state should not further delay SSUTA membership, and if it wishes to collect tax from internet retailers, should adopt legislation similar to or more generous than South Dakota’s.

The remaining states in this group have not yet passed South Dakota-style legislation or regulations relating to internet sales, but would have to undertake significant simplifications prior to doing so:

- Arizona is not a SSUTA member but tackled a major roadblock with central administration of its 131 sales tax jurisdictions (called the Transactions Privilege Tax) beginning January 1, 2017. Each local jurisdiction still determines its own tax base, however. The state should pursue SSUTA membership and/or significant simplification of its local sales taxes prior to pursuing enabling legislation similar to South Dakota’s.

- California is not a SSUTA member and has 323 sales tax jurisdictions. The state provides central collection and local sales taxes must adhere to the state sales tax base, but the state does not adhere to common definitions or provide base/rate lookup software (aside from a website). The state should pursue SSUTA membership and/or significant simplification of its local sales taxes prior to pursuing enabling legislation similar to South Dakota’s.

- Florida is not a SSUTA member and has 69 sales tax jurisdictions. The state provides central collection and local sales taxes must adhere to the state sales tax base, but the state does not adhere to common definitions or provide base/rate lookup software (aside from a website). The state should pursue SSUTA membership and/or significant simplification of its local sales taxes prior to pursuing enabling legislation similar to South Dakota’s.

- Idaho is not a SSUTA member and has 11 sales tax jurisdictions. The state provides central collection and local sales taxes must adhere to the state sales tax base, but the state does not adhere to common definitions or provide base/rate lookup software. The state should pursue SSUTA membership prior to pursuing enabling legislation similar to South Dakota’s.

- Maryland is not a SSUTA member and has no local sales tax jurisdictions. The state does not adhere to common definitions, deviates from a standard “rounding” rule, and does not provide base lookup software (aside from a website), but does have centralized collection of sales tax. (Maryland has no local sales taxes.) Maryland’s Comptroller has proposed a draft regulation[91] to adopt a $100,000 or 200-transaction threshold, in the previous or current calendar years, effective October 1, 2018. While the state should pursue SSUTA membership, the lack of local sales tax jurisdictions does somewhat reduce the burden on interstate sellers.

- Missouri is not a SSUTA member and has 1,393 sales tax jurisdictions. The state provides central collection and local sales taxes must adhere to the state sales tax base, but the state does not adhere to common definitions or provide base/rate lookup software (aside from a website). The state should pursue SSUTA membership and/or significant simplification of its local sales taxes prior to pursuing enabling legislation similar to South Dakota’s.

- New Mexico is not a SSUTA member and has 144 sales tax jurisdictions. The state provides central collection and local sales taxes must adhere to the state sales tax base, but the state does not adhere to common definitions or provide base/rate lookup software (aside from a website). The state should pursue SSUTA membership and/or significant simplification of its local sales taxes prior to pursuing enabling legislation similar to South Dakota’s.

- New York is not a SSUTA member and has 82 sales tax jurisdictions. The state provides central collection and local sales taxes must adhere to the state sales tax base, but the state does not adhere to common definitions or provide base/rate lookup software (aside from a website). The state should pursue SSUTA membership and/or significant simplification of its local sales taxes prior to pursuing enabling legislation similar to South Dakota’s.

- South Carolina is not a SSUTA member and has 45 sales tax jurisdictions. The state provides central collection and local sales taxes must adhere to the state sales tax base, but the state does not adhere to common definitions or provide base/rate lookup software (aside from a website). State officials are considering a draft regulation[92] to require collection by remote sellers with at least $250,000 in sales, in the prior year or in the current year up to the last day of the last calendar month, effective October 1, 2018. The state should pursue SSUTA membership and/or significant simplification of its local sales taxes prior to pursuing enabling legislation similar to South Dakota’s.

- Texas is not a SSUTA member and has 1,594 sales tax jurisdictions. The state provides central collection and local sales taxes must adhere to the state sales tax base, but the state does not adhere to common definitions or provide base/rate lookup software (aside from a website). The state should pursue SSUTA membership and/or significant simplification of its local sales taxes prior to pursuing enabling legislation similar to South Dakota’s. The Texas Comptroller has issued a statement[93] inviting input for future legislation and disavowing any retroactive application.

- Virginia is not a SSUTA member and has 174 sales tax jurisdictions. The state provides central collection and local sales taxes must adhere to the state sales tax base, but the state does not adhere to common definitions or provide base/rate lookup software (aside from a website). The state should pursue SSUTA membership and/or significant simplification of its local sales taxes prior to pursuing enabling legislation similar to South Dakota’s.

- District of Columbia is not a SSUTA member and has no local sales tax jurisdictions. D.C. does not adhere to common definitions or provide base lookup software (aside from a website). D.C. should pursue SSUTA membership prior to pursuing enabling legislation similar to South Dakota’s.

Red Light: Colorado and Louisiana

Colorado and Louisiana have duplicative, outdated, inconsistent, and inefficient sales tax collection mechanisms that make it unlikely that any attempt to pass a South Dakota-style law would survive a legal challenge. Both states permit each tax jurisdiction (328 in Colorado, 370 in Louisiana) to administer, collect, and auditA tax audit is when the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) conducts a formal investigation of financial information to verify an individual or corporation has accurately reported and paid their taxes. Selection can be at random, or due to unusual deductions or income reported on a tax return. its sales tax separately, and define its base independently of the state sales tax base. Neither state is a member of SSUTA and therefore neither adheres to common definitions or provide base/rate lookup software. Adopting sales tax practices that are used by every other state, such as centralized collection of all sales taxes in the state and uniformity between the state and local bases, would be essential prerequisites before Colorado or Louisiana could take advantage of the Wayfair ruling. Both states are aware of these deficiencies and have in recent months begun taking tentative steps to improve their sales tax systems.

- Colorado has a preexisting notice-and-reporting law[94], applying to vendors with in-state sales of at least $100,000 per year. Colorado began enforcement of that law on July 1, 2017. The state’s Sales and Use Tax Simplification Task Force[95] is currently meeting to consider possible changes to sales tax administration and structure.

- Louisiana nonetheless enacted a law[96] adopting a $100,000 or 200-transaction threshold, during the previous or current calendar year, with the Department of Revenue setting an effective date[97] of January 1, 2019. The law establishes[98] a new Sales and Use Tax Commission for Remote Sellers to serve as the single collection entity for remote seller sales taxes, and a Uniform Local Sales Tax Board to promote uniformity and efficiency in local sales tax administration. Both of these new entities have only just begun their work. There is discussion of having remote sellers collect at a uniform rate of 8.45 percent.

NOMAD States: Alaska, Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oregon

These developments are unpopular with online retailers in these five states, which have no statewide sales tax, as they must now collect tax on sales to customers in other states. (Alaska and Montana have limited local sales taxes, which would require centralized collection if internet sales were to be subject to them.) New Hampshire considered a proposal that would limit the ability of other states to subject New Hampshire businesses to collection obligations unless those other states adopted designated minimum simplifications, but that bill did not pass the New Hampshire Legislature[99] due to constitutional concerns.

Marketplaces

One open question is marketplace facilitators: websites such as eBay[100] or Etsy[101] that do not sell goods directly but provide a platform for sellers. The issue of who should collect tax on such transactions was not addressed by South Dakota’s law or the Wayfair case, and whether states have the power to require marketplaces to collect tax is an unresolved question. On one hand it is probably the least complicated option for these websites to collect on behalf of their sellers, but on the other are potentially unintended consequences from redefining who the seller, or merchant of record, is for transactions.

Several states have enacted laws requiring marketplaces to collect for their sellers:

- Alabama law[102] requires marketplace facilitators to collect and remit tax on behalf of their sellers if they facilitate in-state sales of at least $250,000 during the preceding 12-month period, effective January 1, 2019.

- Arizona requires[103] marketplaces to collect for any sellers who have nexus in the state.

- Connecticut law[104] requires marketplace facilitators to collect and remit tax on behalf of their sellers if they facilitate in-state sales of at least $250,000 during the preceding 12-month period ending September 30, effective December 1, 2018.

- Minnesota law[105] requires marketplace facilitators to collect and remit tax on behalf of their sellers if they facilitate in-state sales of at least $10,000 during the preceding 12-month period ending on any calendar quarter, effective October 1, 2018.

- Oklahoma law[106] includes a notice-and-reporting requirement for marketplaces with more than $10,000 in sales in the state in the preceding 12 calendar months, and marketplaces must either collect the tax or comply with the notice-and-reporting provision, effective July 1, 2018.

- Pennsylvania law[107] includes a notice-and-reporting requirement for marketplaces with more than $10,000 in sales in the state in the preceding 12 calendar months, and marketplaces must either collect the tax or comply with the notice-and-reporting provision, effective March 1, 2018.

- Rhode Island law[108] requires marketplaces, called retail sale facilitators[109], with at least $100,000 in sales or 200 transactions in the preceding 12 calendar months, to annually provide a list of names and addresses for in-state retailers for whom the marketplace did and did not collect tax, effective January 15, 2018.

- Washington law[110] includes a notice-and-reporting requirement for marketplaces with more than $10,000 in sales in the state in the preceding 12 calendar months, and marketplaces must either collect the tax or comply with the notice-and-reporting provision, effective January 1, 2018.

Additionally, South Carolina is considering a draft regulation[111] to require collection by marketplaces with at least $250,000 in the prior year or in the current year up to the last day of the last calendar month, effective October 1, 2018.

Changes to marketplace taxation should only be done through legislative action, not administrative rule-making, and with sufficient notice.

Conclusion

As with any tax change, policymakers will be best served in approaching this issue in a deliberate fashion and with eyes wide open to second-order effects. The end goal of extending state sales taxes to online transactions is a broader, more stable sales tax base. Because that goal will impact state finances for years to come, policymakers should build systems meant to last; ones that are surely constitutional, that are free from the threat of lawsuit, and that uphold a system of voluntary compliance.

Notes

[1] The authors would like to acknowledge the following online resources: Karl Frieden & Fred Nicely, “The Best and Worst of State Sales Tax Systems,” Council on State Taxation, Apr. 2018, https://www.cost.org/globalassets/cost/state-tax-resources-pdf-pages/cost-studies-articles-reports/the-best-and-worst-of-state-sales-tax-systems-august-17-2018-final.pdf; Avalara, “Ecommerce,” https://www.avalara.com/us/en/blog/category/ecommerce.html; Streamlined Sales Tax Governing Board, “State Info,” https://www.streamlinedsalestax.org/index.php?page=state-info; Vertex, as cited in Katherine Loughead, “Growing Number of State Sales Tax Jurisdictions Makes South Dakota v. Wayfair That Much More Imperative, Tax Foundation, Apr. 17, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/growing-number-state-sales-tax-jurisdictions-makes-south-dakota-v-wayfair-much-imperative. The author also acknowledges the research assistance of Jared Walczak and Loic Fremond.

[2] Technically, the tax being collected is the state’s use tax, a tax imposed at an identical rate as the sales tax on any purchase by a resident where sales tax has not otherwise been collected.

[3] On April 28, 2016, South Dakota notified four companies of the pending effective date. Three of the companies (Wayfair, Overstock.com, and Newegg) refused to collect, citing Quill, and sued. By the law’s own terms, its enforcement was suspended until the conclusion of legal proceedings. On January 17, 2017, a federal court declined to entertain jurisdiction, considering it a state tax matter. On March 6, 2017, a South Dakota Sixth Judicial Circuit judge ruled in favor of Wayfair, citing Quill. The South Dakota Supreme Court heard oral argument on August 29, 2017, and issued its opinion shortly thereafter, affirming the trial court. The petition for writ of certiorari followed on October 2, 2017, and was granted on January 12, 2018. Oral argument was heard on April 17 and the decision handed down on June 21.

[4] Chris Atkins, “Important Tax Cases: Complete Auto Transit v. Brady and the Constitutional Limits on State Tax Authority” Tax Foundation, 2005.

[5] The Court cited Wayfair’s website, which stated, “One of the best things about buying through Wayfair is that we do not have to charge sales tax.”

[6] On the latter point, the Court referenced the Tax Foundation’s brief cataloging laws passed in 31 states to require tax collection by internet retailers within the physical presence framework. These laws include New York-style “click-through nexus” laws, Colorado-style “notice and reporting” laws, and Massachusetts-style “cookie nexus” laws.

[7] This could be a reference to the Due Process Clause, other parts of the Complete Auto test, or the Pike balancing test. The Due Process question of to what extent a state can regulate an out-of-state entity is therefore left for another day. Pike compares the benefits to the state and burdens on the interstate business for a law otherwise valid under the Commerce Clause. The Pike test is very deferential to the state and therefore tough for a taxpayer to win.

[8] Joseph Bishop-Henchman, “Testimony: Post-Wayfair Options for Congress” Tax Foundation, 2018.

https://taxfoundation.org/post-wayfair-options-congress.

[9] National Congress of State Legislators (NCSL), “Principles of State Implementation after South Dakota v. Wayfair”, Remote Sales Tax Collection Principles, 2018, http://www.ncsl.org/documents/taskforces/SALT_SD_vs_Wayfair.pdf.

[10] See, e.g., Associated Industries of Missouri v. Lohman, 511 U.S. 641 (1994) (invalidating a use tax which exceeds the sales tax as discriminating against interstate commerce). Cf. Metropolitan Life Ins. Co. v. Ward, 470 U.S. 869 (1985) (invalidating as an Equal Protection Clause violation a higher insurance premium tax on foreign corporations than domestic corporations); Williams v. Vermont, 472 U.S. 14 (1985) (invalidating as an Equal Protection Clause violation a purchase and use tax on motor vehicles where the tax was credited only if the purchaser was a Vermont resident).

[11] United States Government Accountability Office, “States Could Gain Revenue from Expanded Authority, but Businesses Are Likely to Experience Compliance Costs”, Report to Congressional Requesters GAO-18-114, 2017, https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/688437.pdf.

[12] Nicole Kaeding, “Prioritizing Tax Reform in Arkansas”, Tax Foundation, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/prioritizing-tax-reform-arkansas.

[13] Jared Walczak, “Two States Cut Taxes Due to Federal Tax Reform”, Tax Foundation, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/two-states-cut-taxes-due-federal-tax-reform.

[14] Jared Walczak, “What’s in the Iowa Tax Reform Package”, Tax Foundation, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/whats-iowa-tax-reform-package.

[15] Morgan Scarboro, “Kentucky Legislature Overrides Governor’s Veto to Pass Tax Reform Package”, Tax Foundation, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/kentucky-tax-reform-package.

[16] Patrick Anderson, “U.S. Supreme Court ruling could mean lower South Dakota sales tax. Eventually.”, Argus Leader, 2018, https://www.argusleader.com/story/news/business-journal/2018/07/25/south-dakota-sales-tax-governor-daugaard-wayfair/833042002.

[17] CCH Tax Group, “Utah Might Expand Manufacturing Exemption”, Wolters Kluwer, 2018, http://news.cchgroup.com/2018/05/21/utah-might-expand-manufacturing-exemption.

[18] Katherine Loughead, “Online Sales Tax Revenue Presents Opportunity for Permanent, Comprehensive Reform in Wisconsin”, Tax Foundation, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/online-sales-tax-comprehensive-permanent-tax-reform-wisconsin.

[19] Matthew DeFour, Mark Somerhauser, “Wisconsin could reap $187 million a year from Internet sales tax — but there’s a catch”, Wisconsin State Journal, 2018, https://madison.com/wsj/news/local/govt-and-politics/wisconsin-could-reap-million-a-year-from-internet-sales-tax.

[20] Ga. H.B. 61 (sec. 2 C.2(1)(A)).

[21] Ind. Code § 6-2.5-2.1.

[22] Indiana Statehouse Files “Indiana Going After Online Sales Tax,” Nuovo Independent News 2018, https://www.nuvo.net/news/indiana-going-after-online-sales-tax.

[23] Indiana Department Of Revenue “South Dakota V. Wayfair, Inc.,” Department of Revenue 2018, https://www.in.gov/dor/6367.

[24] Iowa State Senate, “Senate File 2417” Committee On Ways And Means 2018

[25] Iowa Department of Revenue, https://tax.iowa.gov/south-dakota-v-wayfair.

[26] Ky. Rev. Stat § 139.340.

[27] Kentucky Department of Revenue, https://revenue.ky.gov/News/Pages/Kentucky-Sales-and-Use-Tax-Collections-by-Remote-Retailers-U.S.-Supreme-Court-Ruling.

[28] N.J. Stat. § A4261.

[29] N.J. Department of the Treasury, “Sales and Use Tax Information for Remote Sellers Effective October 1, 2018”, 2018, https://www.state.nj.us/treasury/taxation/remotesellers.

[30] N.D. Code § 57-40.2.

[31] Tripp Baltz, “State of Wayfair: Utah Tax Officials Feeling, Umm, Taxed,” Bloomberg BNA, 2018, https://www.bna.com/state-wayfair-utah-n73014477303.

[32] State of North Dakota, “Remote Seller Sales Tax”, https://www.nd.gov/tax/remoteseller.

[33] S.D. S.B. 106.

[34] SD Department of Revenue “Remote Sellers”, https://dor.sd.gov/taxes/business_taxes/remoteseller.

[35] Utah § S.B 2001 (2018).

[36] Utah State Tax Commission, “Sales Tax on Internet Purchases: South Dakota v. Wayfair Court Decision”, https://tax.utah.gov/current-news. ,

[37] Vt. Stat. tit. 32 § 9701.

[38] Dave Gram, “Vermont eases the squeeze on online, out-of-state sales tax”, VTDigger, 2017, https://vtdigger.org/2017/12/06/vermont-eases-the-squeeze-for-substitute-sales-tax.

[39] Agency of Administration, Department of Taxes, “South Dakota V. Wayfair”, http://tax.vermont.gov/business-and-corp/sales-and-use-tax/sales-and-use/wayfair.

[40] Wyo. Stat. § 39-15-501.

[41] Wyoming Department of Revenue, “Notice of Collection Authority,” 2018, https://0ebaeb71-a-84cef9ff-s-sites.googlegroups.com/a/wyo.gov/wy-dor/Noticeofcollectionauthority.pdf.

[42] Arkansas Department of Finance Administration (DFA), “Arkansas Remote Seller Frequently Asked Questions”, https://www.dfa.arkansas.gov/excise-tax/sales-and-use-tax/arkansas-remote-seller-frequently-asked-questions-faqs.

[43] Nicole Kaeding, “Prioritizing Tax Reform in Arkansas”, Tax Foundation, 2018 https://taxfoundation.org/prioritizing-tax-reform-arkansas/.

[44] State of Michigan Department of Treasury (DOT), “Sales and use tax nexus standards for remote sellers”, Revenue and Administrative Bulletin for 2018-16”, 2018, https://www.michigan.gov/taxes/0,4676,7-238-43519_43529-474288–,00.html.

[45] State of Michigan Department of Treasury (DOT), “Sales and use tax nexus standards for out of state sellers”, Revue and Administrative Bulletin for 2015-22”, 2015, https://www.michigan.gov/documents/treasury/RAB_2015-22_-_Nexus_Standards_505107_7.pdf.

[46] Minnesota Department of Revenue (DOR) “News release: remote sellers”, 2018, http://www.revenue.state.mn.us/newsroom/Documents/20180725%20Wayfair%20Update.pdf; Minn. Stat. § 297A.66(3)(d).

[47] Nebraska Department of Revenue (DOR), “News Release: Regarding the South Dakota v. Wayfair United States

Supreme Court Decision”, 2018, http://www.revenue.nebraska.gov/news_rel/jul_18/wayfair.pdf.

[48] Nevada Department of Taxation (DOT), “remote Sellers Proposed Regulations”, https://tax.nv.gov/FAQs/LCB-File-No-R189-18.

[49] State of Nevada Department of Taxation (DOT), “Notice of Intent to Act Upon Regulation”, Nevada Tax Commission, 2018, https://tax.nv.gov/uploadedFiles/taxnvgov/Content/FAQs/Adoption-Notice-R189-18.pdf.

[50] North Carolina Department of Revenue, “Sales and Use Tax Collections on Remote Sales – SD-18-6”, 2018, https://files.nc.gov/ncdor/documents/files/sd-18-6_0.pdf; cf. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 105-264.

[51] Ohio Taxation (@OhioTaxation). “Statement on the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling of South Dakota vs. Wayfair Inc.,” Jun. 21, 2018, 1:21 p.m. Tweet, https://twitter.com/OhioTaxation/status/1009894000009056256.

[52] Alex Ebert, “Online Retailers Sue to Scorch Ohio’s ‘Cookie’ Sales Tax”, Bloomberg BNA, 2018, https://www.bna.com/online-retailers-sue-n73014473733.

[53] Okla. H.B. § 1019. Governor Fallin vetoed S.B. 337, which would have established a $100,000 threshold.

[54] Rhode Island Department of Revenue (DOR), “Non-collecting retailers, referrers, and retail sales facilitators”, Division of Taxation, http://www.tax.ri.gov/Non-collecting%20retailers/index.php.

[55] Rhode Island Department of Revenue (DOR), “FAQS FOR NON-COLLECTING RETAILERS (REMOTE

SELLERS) FOLLOWING WAYFAIR DECISION” Division of Taxation, 2018, http://www.tax.ri.gov/notice/Remote_seller_FAQs_07_06_18.pdf.

[56] Washington State Department of Revenue (DOR), “Washington to begin collecting sales tax from out-of-state sellers”, 2018, https://dor.wa.gov/about/news-releases/2018/washington-begin-collecting-sales-tax-out-state-sellers.

[57] Wash. H.B. § 2163 (2017)

[58] Kristen Moritz-Baune, “Washington enacts use tax reporting and B&O changes for remote sellers”, RSM Tax Alert, 2017, https://rsmus.com/what-we-do/services/tax/state-and-local-tax/washington-enacts-use-tax-reporting-and-b-o-changes-for-remote-s.

[59] Washington State Department of Revenue, “Registration thresholds for out-of-state businesses: retail sales FAQ”, https://dor.wa.gov/find-taxes-rates/retail-sales-tax/marketplace-fairness-leveling-playing-field/registration-thresholds-out-state-businesses-retail-sales.

[60] Wisconsin Department of Revenue (DOR), “Remote Sellers – Wayfair Decision”, https://www.revenue.wi.gov/Pages/Businesses/remote-sellers.aspx.

[61] Ala. Code § 40-23-31 & Ala. Code § 40-23-83.

[62] Alabama Department of Revenue, ” Simplified Sellers Use Tax FAQs”, https://revenue.alabama.gov/sales-use/simplified-sellers-use-tax-ssut/simplified-sellers-use-tax-faqs.

[63] Alabama Department of Revenue, “My Alabama Taxes”, https://myalabamataxes.alabama.gov.

[64] Alabama Department of Revenue, “Simplified Sellers Use Tax (SSUT)”, https://revenue.alabama.gov/sales-use/simplified-sellers-use-tax-ssut.

[65] Gail Cole, “The sleeping giant awakens: California looks for best way to tax out-of-state sellers”, Avalara Tax Compliance, 2018, https://www.avalara.com/us/en/blog/2018/08/sleeping-giant-awakens-california-looks-to-tax-out-of-state-sellers.html.

[66] California Department Of Tax And Fee Administration (CDTFA), “Tax Guide for New Tax Collection Requirements for Retailers Making Sales for Delivery into California”, 2018, http://src.bna.com/Alh.

[67] Id.

[68] Conn. S.B. 417.

[69] Gail Cole, “Connecticut amends economic nexus law, taxes marketplace facilitators”, Avalara Tax Compliance, 2018, http:// avalara.com/us/en/blog/2018/06/connecticutamendseconomicnexuslawtaxesmarketplacefacilitators.

[70] Haw. S.B. 2514.

[71] Hawaii Department of Taxation, “Implementation of Act 41”, Announcement No. 2018-10, 2018, http://files.hawaii.gov/tax/news/announce/ann18-10_amended.pdf.

[72] Avalara Tax Compliance, “Idaho plays hard ball with non-collecting remote retailers”, 2018, https://www.avalara.com/us/en/blog/2018/08/idaho-plays-hard-ball-with-non-collecting-remote-retailers.

[73] Ill H.B. 3342 (sec. 80-5(9)).

[74] Illinois Department of Revenue, “Locally Imposed Sales Taxes Administered by the Department of Revenue”, http://tax.illinois.gov/Publications/LocalGovernment/ST-62.pdf.

[75] Ill. Comp. Stat. 20/2520.

[76] Illinois Department of Revenue, “Claims for Credit” Sales Tax Letter 13—0029-GIL, 2013, http://www.revenue.state.il.us/LegalInformation/LetterRulings/st/2013/ST-13-0029.pdf.

[77] Illinois Department of Revenue, “Sales & Use Taxes”, http://tax.illinois.gov/Businesses/TaxInformation/Sales/rot.

[78] Me. Stat. tit. 36, E Title 36 § 1951-B(3).

[79] Maine Revenue Service (MRS), “Guidance for Remote Sellers”, 28(6), 2018, https://www.maine.gov/revenue/publications/alerts/2018/ta_aug2018_vol28_iss6.html.

[80] 830 Mass. Code Regs. 64H.1.7, https://www.mass.gov/regulations/830-CMR-64h17-vendors-making-internet-sales.

[81] Gail Cole, “Remote online seller tries to crush Massachusetts cookie law”, Avalara Tax Compliance, 2018, https://www.avalara.com/us/en/blog/2017/10/remote-online-seller-tries-crush-massachusetts-cookie-law.

[82] Gail Cole, “Massachusetts swallows tax on internet cookies … for now”, Avalara Tax Compliance, 2018, https://www.avalara.com/taxrates/en/blog/2017/07/massachusetts-swallows-tax-internet-cookies-now.

[83] Miss. Code R. § 35.IV.3.09.

[84] Mississippi Department of Revenue, “Sales and Use Tax Guidance for Online Sellers”, http://www.dor.ms.gov/Business/Documents/Online%20Seller%20Guidance.pdf.

[85] Pa. H.B. 542.

[86] Pennsylvania Department of Revenue, “Advice for Remote Sellers”, https://www.revenue.pa.gov/GeneralTaxInformation/Tax%20Types%20and%20Information/SUT/MarketPlaceSales/Pages/Remote-Sellers.

[87] PDOR, “SALES & USE TAX TAXABILITY LISTS,” https://revenue.pa.gov/GeneralTaxInformation/Tax%20Types%20and%20Information/SUT/Pages/Taxability%20Lists.

[88] Tennessee Department of Revenue, “State Sale and Use Tax Rules” Rules of Department of Revenue 1320(05-01), 40, 2017, https://publications.tnsosfiles.com/rules/1320/1320-05/1320-05-01.20170101.pdf#page=40.

[89] Tripp Baltz, “State of Wayfair: Tennessee Collections on Hold”, BNA Bloomberg, 2018, http://src.bna.com/nPZ. https://www.bna.com/state-wayfair-tennessee-n73014481801; American Catalog Mailers Association v. Tennessee Department of Revenue, No. 17-307-IV (Tenn. Chancery Ct.), Agreed Order Preventing Enforcement,

[90] “Tennessee Full SST Member”, 2005, https://www.streamlinedsalestax.org/index.php?page=tennessee.

[91] Maryland Comptroller of Revenue, “Draft Regulations Submitted to AELR Committee,” http://src.bna.com/AUm.

[92] Retailers Without a Physical Presence, SC Revue 18 (proposed August 2018), to be codified SC Revenue Ruling #14-4, https://dor.sc.gov/resources-site/lawandpolicy/Advisory%20Opinions/Public%20Draft%20-Remote%20Seller.pdf.

[93] Glenn Hagar, Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts (TCPA), “Comptroller Issues Initial Guidance on Remote Seller Sales Tax Decision by U.S. Supreme Court”, June 2018, https://comptroller.texas.gov/about/media-center/news/2018/180627-wayfair.php.

[94] See Colorado Department of Revenue, “Use Tax – Information for Non-Collecting Retailers,” https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/tax/use-tax-information-non-collecting-retailers.

[95] Colorado General Assembly (CGA), “Sales and Use Tax Simplification Task Force”, Fiscal Policy & Taxes, 2018, https://leg.colorado.gov/committees/sales-and-use-tax-simplification-task-force/2018-regular-session.

[96] 2018 La. HB 17 Sec.1 §301(4)(m).

[97] Louisiana Sales and Use Tax Commission for Remote Sellers (LSUTCRS), “Impact of Wayfair Decision on Remote Sellers Selling to Louisiana Purchasers”, Remote Sellers Information Bulletin, 18(001), 2018, http://revenue.louisiana.gov/LawsPolicies/RSIB%2018-001%20-%20Remote%20Sellers%20Impact%20of%20Wayfair.pdf.

[98] Gail Cole, “Louisiana takes steps to simplify sales and use tax administration”, Avalara Tax Compliance, 2017, https://www.avalara.com/taxrates/en/blog/2017/07/louisiana-takes-steps-to-simplify-sales-and-use-tax-administration.

[99] Kevin Landrigan, “NH lawmakers kill internet sales-tax bill”, New Hampshire Union Leader, 2018, http://www.unionleader.com/state-government/nh-lawmakers-kill-internet-sales-tax-bill–20180725.

[100] eBay News Team, “Supreme Court Rules on Internet Sales Tax”, 2018, https://www.ebayinc.com/stories/news/supreme-court-decision-in-south-dakota-v-wayfair.

[101] Etsy News Team, “Etsy Responds to U.S. Supreme Court Decision”, 2018, https://blog.etsy.com/news/2018/etsy-responds-to-u-s-supreme-court-decision.

[102] Ala. H.B. 470 (2018).

[103] Arizona Department of Revenue (ADR), “Arizona Transaction Privilege Tax Ruling (TPR)”, 16-3, https://azdor.gov/sites/default/files/media/RULINGS_TPT_2016_tpr16-3.pdf.

[104] Conn. S.B. 417 (2018).

[105] Minnesota Department of Revenue (MDR), “Update for Marketplace Providers” Sales and Use Tax, 2018, http://www.revenue.state.mn.us/businesses/sut/Pages/Marketplace-Providers.

[106] Okla. H.B. 1019 (2018).

[107] Pennsylvania Department of Revenue (PDOR), “MARKETPLACE FACILITATORS”, Tax Types and Information, 2018, https://revenue.pa.gov/GeneralTaxInformation/Tax%20Types%20and%20Information/SUT/MarketPlaceSales/Pages/Marketplace-Facilitators.aspx?

[108] Rhode Island Department of Revenue (RIDR), “Non-collecting retailers, referrers, and retail sales facilitators”, Division of Taxation, 2018, http://www.tax.ri.gov/Non-collecting%20retailers/index.php

[109] RIDR, “NOTICE: TO ALL RETAIL SALE FACILITATORS”, Division Of Taxation, 2018, http://www.tax.ri.gov/notice/Notice%202017-03%20–%20Retail%20Sale%20Facilitator%20Notice%20–%2008-04-17.pdf

[110] Washington Department of Revenue (WDR), “Marketplace sellers”, Marketplace Fairness, 2018, https://dor.wa.gov/find-taxes-rates/retail-sales-tax/marketplace-fairness-leveling-playing-field/marketplace-sellers.

[111] Online Marketplaces – Physical and Economic Nexus, SC REVENUE RULING #18, (proposed 27 August 2018), https://dor.sc.gov/resources-site/lawandpolicy/Advisory%20Opinions/Public%20Draft%20-Marketplace%20Operator.pdf.

Share this article