Key Findings

- State taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. collections declined 5.5 percent in FY 2020 according to new Census data, though actual losses are likely to be significantly lower after accounting for the shifting of income tax collections into the current fiscal year due to delayed tax filing deadlines.

- After a sharp initial drop under stay-at-home orders, sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. collections have rebounded, closing the year down 0.3 percent with indications of growth in early FY 2021.

- Individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. collections dropped 10.1 percent year-over-year, but most of this can be attributed to timing effects. However, states should expect sluggish income tax collections in FY 2021.

- Corporate income taxes plummeted 17.5 percent in FY 2020 as businesses went into the red, but fortunately for states, they account for less than 5 percent of state tax revenue.

- Other state taxes suffered as the activities they tax—driving, tourism, and entertainment among them—came to a standstill, and these may take time to recover.

- Local sales and property taxes have proven highly resilient thus far, though municipalities which impose local income taxes may experience distress as employees work remotely from outside their borders.

- The latest tax collection data are consistent with prior projections of FYs 2020 and 2021 underperforming initial projections by just under $200 billion (a decline of $121 billion compared to a FY 2019 baseline), which would represent a loss of far lower magnitude than many initially feared.

Introduction

New U.S. Census data shows state tax collections down 5.5 percent in FY 2020, driven by a dismal final quarter (April through June) as states began to feel the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.[1] After accounting for revenues shifted into the current fiscal year due to delayed income tax filing and payment deadlines, all indications are that the overall decline was in the low single digits—not desirable, certainly, but far better than many feared.

Sales taxes appear to have rebounded, while income tax collections have benefited from federal relief and stimulus spending in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act.[2] And, while local tax data are incomplete, there is good reason to believe that municipal governments are weathering the crisis well thus far.

Overview of the New Data

In the final quarter of FY 2020, revenues were a full 29.0 percent lower than they were in the same quarter one year prior, yielding a decline in annual collections of 5.5 percent. Yet, as bad as that is, the figures offer several glimmers of hope and further bolster the growing realization that state revenue losses are considerably more manageable than many feared in the early days of the pandemic.

Although the hit to FY 2021 revenues is expected to be steeper than the FY 2020 decline—since much of FY 2020 was already in the books when the pandemic hit, and some of the losses from the early days of the pandemic will not show up in state tax revenues until later—these new figures enhance our understanding of the scope of the impact on state revenues. These projections are largely consistent with our earlier estimates that states will experience revenue losses of slightly less than $200 billion in aggregate across FYs 2020 and 2021 compared to initial projections ($121 billion against a FY 2019 baseline).[3]

Sales tax collections took a sharp dip in the final quarter of the fiscal year, but robust collections earlier in the year yielded annual collections almost perfectly on par with FY 2019, and early indications are that sales taxes have recovered nicely in the early months of the new fiscal year.

Income tax collections are more complicated, with individual income tax revenue provisionally down 10.1 percent year-over-year, a figure that is likely to be dramatically overstated due to most states’ decision to delay income tax deadlines from April to July, shifting a fair amount of the revenue into the subsequent fiscal year (beginning July 1).

Corporate income tax revenues plummeted, with states only bringing in half as much corporate tax revenue in the fourth quarter of FY 2020 as they did the same quarter in FY 2019, since corporate income taxes are imposed on net revenue and many companies found themselves in the red early in the pandemic. The drop was enough for corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. collections to close out the year 17.5 percent lower, though this figure is also subject to revision (though much more modestly) due to delayed filing and payment deadlines.

States have little reliance on property taxes—which are mostly imposed at the municipal level—but those that exist at the state level were quite stable, while the remaining state taxes were a mixed bag, with some excise tax revenues vanishing as the activities they tax (like travel, lodging, and entertainment) largely dried up. Once delayed income tax payments are accounted for and shifted to FY 2020, the decline in state tax revenue between FY 2019 and FY 2020 should drop from 5.5 percent to the low single digits.

| Revenue Changes for Full Fiscal Years and for the Final Quarter of Each Fiscal Year | ||

|---|---|---|

| Tax Type | Year-over-Year | Quarter-over-Quarter |

|

Individual Income Taxes |

-10.1% | -38.7% |

|

Corporate Income Taxes |

-17.5% | -50.9% |

|

General Sales Taxes |

-0.3% | -17.3% |

|

State Property Taxes |

2.0% | -2.5% |

|

Other Taxes |

-2.6% | -18.8% |

|

Total Tax Collections |

-5.5% | -29.0% |

|

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau; Tax Foundation calculations. |

||

Sales Tax Revenues

Sales tax revenues only declined 0.3 percent from FY 2019 to FY 2020 despite the final quarter’s receipts coming in 17.3 percent lower than those in the last quarter of FY 2019. Flat collections—a relief under the circumstances—can be attributed to robust sales tax revenues earlier in the year, with collections up 6.4 percent over the prior year’s totals for the first three quarters. This reflects both a strong economy prior to the pandemic and states’ continued success generating revenue from remote (online) sales as their post-Wayfair remote seller and marketplace facilitator regimes hit their stride.[4]

The 17.3 percent decline in the final quarter of FY 2020 would be alarming if there were good cause to believe the slide has continued into the current fiscal year, but all available evidence—Census data, a smattering of monthly receipts from select states, and industry reports—shows a strong rebound in consumption and taxable sales beginning in June. (Due to the timing of sales tax remittances, the revenue recovery would begin to show up in July.) Retail sales plummeted at the height of business closure orders and stay-at-home mandates, but the decline did not last.

Census data on retail sales and food services shows sales trending about 4.6 percent higher than the previous year for January and February before dipping in March and plunging in April, when retail volume was 19.9 percent lower than the same month the previous year.[5] Overall retail sales were down 7.7 percent in the fourth quarter compared to the same quarter in the previous fiscal year, and this understates the impact on taxable sales, since many people were stockpiling groceries and other largely untaxed items at the time.

By June, however, monthly sales tax collections were again higher than they were the same month the previous year, and they have remained so through August (most recent data). While any number of factors—the expiration of benefits, another wave of the virus, a new round of business closures—could cause sales volume to decline again, for now the data are consistent with a steep but relatively brief dip in taxable sales, with sales and use taxes poised to perform well in FY 2021.

Income Tax Revenues

Income tax revenues in the final quarter of FY 2020 came in extremely low. Individual income tax receipts were 38.7 percent lower than they were a year previously, and corporate income tax collections were down 50.9 percent, resulting in year-over-year declines of 10.1 and 17.5 percent, respectively. Particularly with individual income taxes, however, this is largely the consequence of delayed collections due to postponed filing deadlines, not an actual decline in receipts associated with the fiscal year.

The majority of income tax collections in the final quarter of a traditional state fiscal year (ending in June) are typically derived from income earned the previous tax year (in this case, tax year 2019), on which final payments are generally due April 15th. While withholdingWithholding is the income an employer takes out of an employee’s paycheck and remits to the federal, state, and/or local government. It is calculated based on the amount of income earned, the taxpayer’s filing status, the number of allowances claimed, and any additional amount the employee requests. and quarterly estimated payments keep income tax revenues flowing throughout the year, Tax Day remains very important for state revenues—and in all but three states with an income tax, this year’s tax filing deadline was pushed into July, the subsequent fiscal year.[6]

Consider Colorado as an example. In April 2019, the state brought in $1.82 billion in individual income tax revenues, but in April 2020, a billion dollars were shaved off collections, with the state only garnering $819 million. The revenue did not disappear, however; it showed up in July receipts, after the end of FY 2020, where this year saw the state bring in $1.76 billion, compared to only $614 million last year. All told, state individual income tax receipts were 3.4 percent higher for the four months from April to July in 2020 than they were in 2019; only the timing changed.[7]

Or take New York, a state that has been particularly ravaged both by the virus and a worker exodus in its wake—many temporary, some not. New York is unusual in beginning its fiscal year in April rather than July. The state only brought in $8.63 billion in individual income tax collections between April and June, corresponding with the final quarter of FY 2020 for most states, barely half the $16.91 billion the state raised in those same months the previous year. By August, however, the gap had closed substantially—to $21.59 billion compared to $23.15 billion the previous year.[8] New York is still in a hole, but a snapshot of income tax collections through the end of June does not paint an accurate picture.

After shifting delayed collections from tax year 2019 into the FY 2020 budgets (out of FY 2021), what appears to be a stark revenue decline all but disappears. That is the good news. The bad news, unfortunately, is that the major income tax revenue losses should show up in FY 2021, not FY 2020. While income tax withholding and estimated payments are remitted throughout the year, a sizable amount of tax obligations incurred during 2020 will not be paid until April 2021, toward the end of the current fiscal year.

Income tax receipts will, however, be propped up by unemployment compensation, and particularly by the $600 per week Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program and its $300 a week successor, since unemployment benefits constitute taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. Taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. . The Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and other federal aid programs have also served to maintain incomes. The role of both these programs, not only in aiding workers and their employers, but also in enhancing state revenues, has been underappreciated. Boosted by federal relief spending, personal income in the final quarter of FY 2020 was consistent with $20.40 trillion in annual income nationwide, compared to $17.75 trillion the same quarter the previous year.[9]

Corporate income tax receipts, by contrast, are likely to be disappointing throughout FY 2021 as many businesses continue to post losses or demonstrate only modest profits, limiting their tax liability. This extreme volatility is an inherent problem of corporate income taxes, so it is fortunate that corporate income taxes account for less than 5 percent of state tax revenue nationwide.[10]

Other Taxes

While most states impose income and sales taxes, other sources of revenue vary greatly. All impose excise taxes on gasoline, cigarettes, and alcohol, while a growing number have also legalized and taxed marijuana and gaming. Some states generate significant revenue from severance taxes on oil, natural gas, and other natural resources. Others supplement their budgets with tourism-oriented taxes on lodging, rental cars, and dining.

Many of these taxes are impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, and in some cases, it may take time for receipts to recover. While gasoline and diesel sales are on the road to recovery, tourism revenue may remain abysmal for some time. States heavily reliant on oil and natural gas revenues were suffering even before the pandemic as energy prices cratered, yielding particularly dramatic declines in states like Alaska and North Dakota, where extraction costs are sufficiently high to make oil and gas recovery uneconomical at current prices.

Although this catch-all category of other taxes was only down 2.6 percent on the year, the decline at the end of the fiscal year may be hard for states to shake. Receipts were down 18.8 percent in the final quarter of FY 2020 compared to the same quarter in FY 2019. Unlike with income taxes, this is not a timing shift, and unlike with sales taxes, there is not a dramatic rebound so much as what looks to be a gradual recovery.

Total Revenues

Total state tax collections were about $59 billion (5.5 percent) lower in FY 2020 than in FY 2019, though once delayed income tax collections are accounted for, that gap should close markedly, if it is not eliminated outright. In the final analysis, FY 2020 tax collections are likely to be better than our July estimate (-$41 billion)[11] and significantly better than late April estimates from Moody’s Investors Service (-$121 billion).[12] States had, however, been anticipating 3.0 percent revenue growth in FY 2020,[13] and final receipts will certainly fall short of that mark, even if they approach the prior year’s baseline.

We have previously estimated that FY 2021 revenues would come in $80 billion lower than FY 2019 actual revenues, or $118 billion lower than initial projections for FY 2021. The latest Census data release is consistent with that estimate, which is also in line with estimates by the Tax Policy Center and independent academic researchers.[14] Such losses would be significant but not catastrophic, and are considerably better than many had once feared. They are also far lower than the assumptions that drove proposals for state and local relief packages in excess of $1 trillion.

The most recent Census data release does not provide a complete picture of all local tax revenues, but it does permit an evaluation of local property and sales tax revenues, which are responsible for the overwhelming share of all local tax collections (85 percent in FY 2018). For FY 2020, property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services. collections were up 4.8 percent over the previous year, while local sales tax receipts rose 4.7 percent. Other taxes, which often fall on business activities and entertainment, are likely to have experienced an overall decline, but these preliminary data suggest that local revenues were stable in FY 2020.

Property and sales taxes, the bedrock of local government finance, are considerably less volatile than income taxes and other taxes popular at the state level, so this bodes well for FY 2021 as well. Overall stability in local tax revenue, however, will mask losses in certain municipalities, particularly those which impose taxes on earned income. Cities like New York and Philadelphia, which aggressively tax the income of those employed in the city, are losing out on revenue as many employees now work remotely outside their borders.

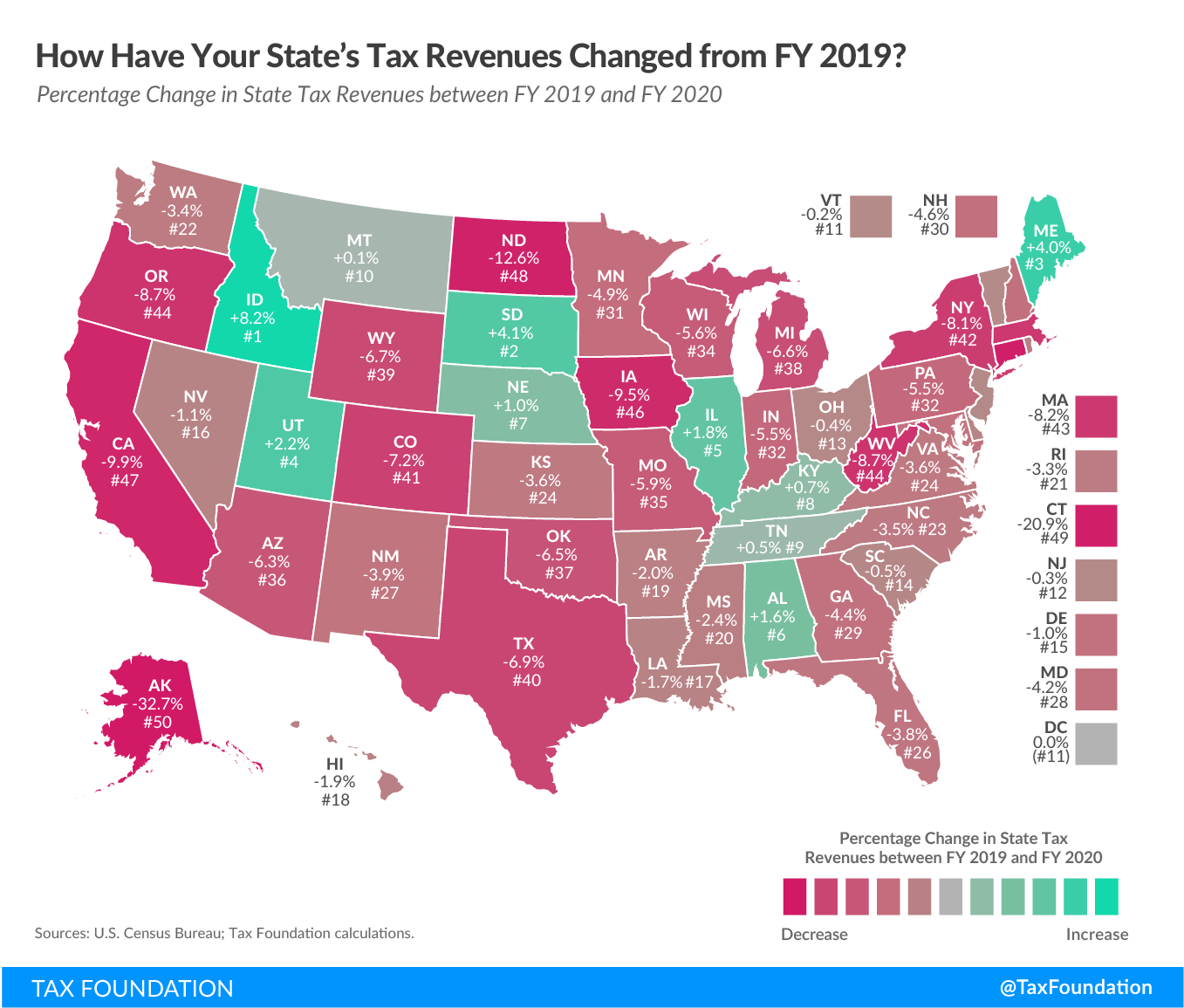

State-by-State Tax Revenues

While state tax collections declined 5.5 percent nationwide, these losses are not evenly distributed. A range of factors contributed to variations in revenue losses. These may include, but are not limited to, the intensity of the virus’s spread in a given state, the strictness and duration of business closure orders, the state’s industry mix, and the stability of the state’s tax code, with states relying more heavily on broad-based consumption taxes faring better than those with a heavy reliance on high-rate income taxes, or whose fortunes are tied to the performance of extractive industries. The following table shows how each state’s FY 2020 tax collections compared to receipts in FY 2019.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe| State | FY 2019 | FY 2020 | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Alabama |

$11.5 | $11.7 | 1.6% |

|

Alaska |

$1.9 | $1.3 | -32.7% |

|

Arizona |

$17.5 | $16.4 | -6.3% |

|

Arkansas |

$10.3 | $10.1 | -2.0% |

|

California |

$188.6 | $169.9 | -9.9% |

|

Colorado |

$15.3 | $14.2 | -7.2% |

|

Connecticut |

$19.1 | $15.1 | -20.9% |

|

Delaware |

$4.6 | $4.5 | -1.0% |

|

Florida |

$45.8 | $44.0 | -3.8% |

|

Georgia |

$24.0 | $23.0 | -4.4% |

|

Hawaii |

$8.2 | $8.0 | -1.9% |

|

Idaho |

$4.9 | $5.3 | 8.2% |

|

Illinois |

$42.5 | $43.3 | 1.8% |

|

Indiana |

$22.2 | $21.0 | -5.5% |

|

Iowa |

$10.6 | $9.6 | -9.5% |

|

Kansas |

$10.0 | $9.7 | -3.6% |

|

Kentucky |

$12.8 | $12.9 | 0.7% |

|

Louisiana |

$12.2 | $11.9 | -1.7% |

|

Maine |

$4.7 | $4.9 | 4.0% |

|

Maryland |

$23.9 | $22.9 | -4.2% |

|

Massachusetts |

$31.5 | $28.9 | -8.2% |

|

Michigan |

$29.8 | $27.8 | -6.6% |

|

Minnesota |

$28.2 | $26.8 | -4.9% |

|

Mississippi |

$8.2 | $8.0 | -2.4% |

|

Missouri |

$13.2 | $12.4 | -5.9% |

|

Montana |

$3.2 | $3.2 | 0.1% |

|

Nebraska |

$5.8 | $5.8 | 1.0% |

|

Nevada |

$10.0 | $9.9 | -1.1% |

|

New Hampshire |

$2.9 | $2.8 | -4.6% |

|

New Jersey |

$38.1 | $37.9 | -0.3% |

|

New Mexico |

$7.6 | $7.3 | -3.9% |

|

New York |

$88.0 | $80.9 | -8.1% |

|

North Carolina |

$29.2 | $28.2 | -3.5% |

|

North Dakota |

$5.0 | $4.3 | -12.6% |

|

Ohio |

$30.7 | $30.6 | -0.4% |

|

Oklahoma |

$10.6 | $9.9 | -6.5% |

|

Oregon |

$12.9 | $11.8 | -8.7% |

|

Pennsylvania |

$41.4 | $39.1 | -5.5% |

|

Rhode Island |

$3.7 | $3.6 | -3.3% |

|

South Carolina |

$11.4 | $11.3 | -0.5% |

|

South Dakota |

$1.9 | $2.0 | 4.1% |

|

Tennessee |

$16.5 | $16.6 | 0.5% |

|

Texas |

$62.9 | $58.5 | -6.9% |

|

Utah |

$9.7 | $9.9 | 2.2% |

|

Vermont |

$3.4 | $3.4 | -0.2% |

|

Virginia |

$24.0 | $23.1 | -3.6% |

|

Washington |

$28.2 | $27.2 | -3.4% |

|

West Virginia |

$6.0 | $5.5 | -8.7% |

|

Wisconsin |

$20.0 | $18.9 | -5.6% |

|

Wyoming |

$2.1 | $2.0 | -6.7% |

|

District of Columbia |

$8.4 | $8.4 | 0.0% |

|

U.S. Total |

$1,076.4 | $1,017.1 | -5.5% |

|

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau; Tax Foundation calculations. |

|||

Conclusion

Revenues for FY 2020 were not what states hoped for when the year began, but for most states, early losses have been manageable. While state forecasters continue to turn a wary eye to the future, the most recent Census tax data is consistent with expectations that FY 2021 tax revenues will come in about 11 percent lower than originally projected—a serious challenge, but not of the magnitude once feared. Initial indications, meanwhile, are that local tax revenues may not have taken as much of a hit, though the gaps in our knowledge here remain considerable.

A new federal relief package appears increasingly unlikely before the next Congress is sworn in, and these new revenue figures, properly understood, do not add much urgency that was previously lacking. The more we learn of states’ revenue shortfalls, the less of a case there is for the expansive aid packages floated in the spring.

Some additional flexible aid for states may, however, still be prudent, whether offered this calendar year or early in the next (in the latter half of FY 2021). Should such a relief package be offered, however, federal lawmakers should take the most recent revenue data into consideration and be careful not to eliminate incentives for state and local governments to prepare for the next downturn or to induce them to undertake imprudent expenditures.

In the final analysis, FY 2020 revenues appear to be a few percentage points below FY 2019 totals, and certainly fall short of initial projections. While hardly good news, it is, perhaps, worthy of a cautious sigh of relief under the circumstances.

[1] U.S. Census Bureau, “Quarterly Summary of State & Local Tax Revenue,” Quarter 2 [calendar year 2020], Sept. 17, 2020, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/econ/qtax/historical/q2.html.

[2] Garrett Watson, Taylor LaJoie, Huaqun Li, and Daniel Bunn, “Congress Approves Economic Relief Plan for Individuals and Businesses,” Tax Foundation, March 30, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/cares-act-senate-coronavirus-bill-economic-relief-plan/.

[3] Jared Walczak, “State Forecasts Indicate $121 Billion 2-Year Tax Revenue Losses Compared to FY 2019,” Tax Foundation, https://taxfoundation.org/state-revenue-forecasts-state-tax-revenue-loss-2020.

[4] Jared Walczak and Janelle Cammenga, “State Sales Taxes in the Post-Wayfair Era,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 19, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/state-remote-sales-tax-collection-wayfair/.

[5] U.S. Census Bureau, Monthly Retail Trade Time Series Data, “Retail and Food Services, total,” https://www.census.gov/retail/marts/www/adv44x72.txt. Data through August 2020, seasonally adjusted.

[6] Katherine Loughead, Janelle Cammenga, Jared Walczak, Ulrik Boesen, Tyler Parks, Rachel Shuster, and Justin DeHart, “Tracking State Legislative Responses to COVID-19,” Tax Foundation, April 30, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/state-tax-coronavirus-covid19/.

[7] Colorado Department of Revenue, “General Fund Net Tax Collections,” multiple months, https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/revenue/general-fund-net-tax-collections.

[8] New York Department of Taxation and Finance, “Monthly Tax Collections Reports,” multiple months, https://www.tax.ny.gov/research/collections/monthly_tax_collections.htm.

[9] U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, GDP & Personal Income, “Personal Income and Its Disposition” (Table 2.1), https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm.

[10] U.S. Census Bureau, “Quarterly Summary of State & Local Tax Revenue.”

[11] Jared Walczak, “State Forecasts Indicate $121 Billion 2-Year Tax Revenue Losses Compared to FY 2019.”

[12] Moody’s Investors Service, “Revenue Recovery from Coronavirus Hit Will Lag GDP Revival, Prolonging Budget Woes,” Apr. 24, 2020.

[13] National Association of State Budget Officers, “Fiscal Survey of the States,” Spring 2020, 40, https://www.nasbo.org/reports-data/fiscal-survey-of-states.

[14] Jared Walczak, “State Forecasts Indicate $121 Billion 2-Year Tax Revenue Losses Compared to FY 2019.”

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe