Table of Contents

- Key Findings

- Introduction

- Double Taxation of Corporate Income in the United States

- — Integrated Tax Rates on Corporate Income and the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

- — Integrated Tax Rates on Corporate Income vs. Pass-through Income

- — Integrated Tax Rates on Corporate Income under Biden’s Tax Plan

- Double Taxation of Corporate Income in the OECD

- Distortions Created by the Double Taxation of Corporate Income

- Corporate Integration

- Conclusion

- Appendix

Key Findings

- The TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. Cuts and Jobs Act lowered the top integrated tax rate on corporate income distributed as dividends from 56.33 percent in 2017 to 47.47 percent in 2020; the OECD average is 41.6 percent.

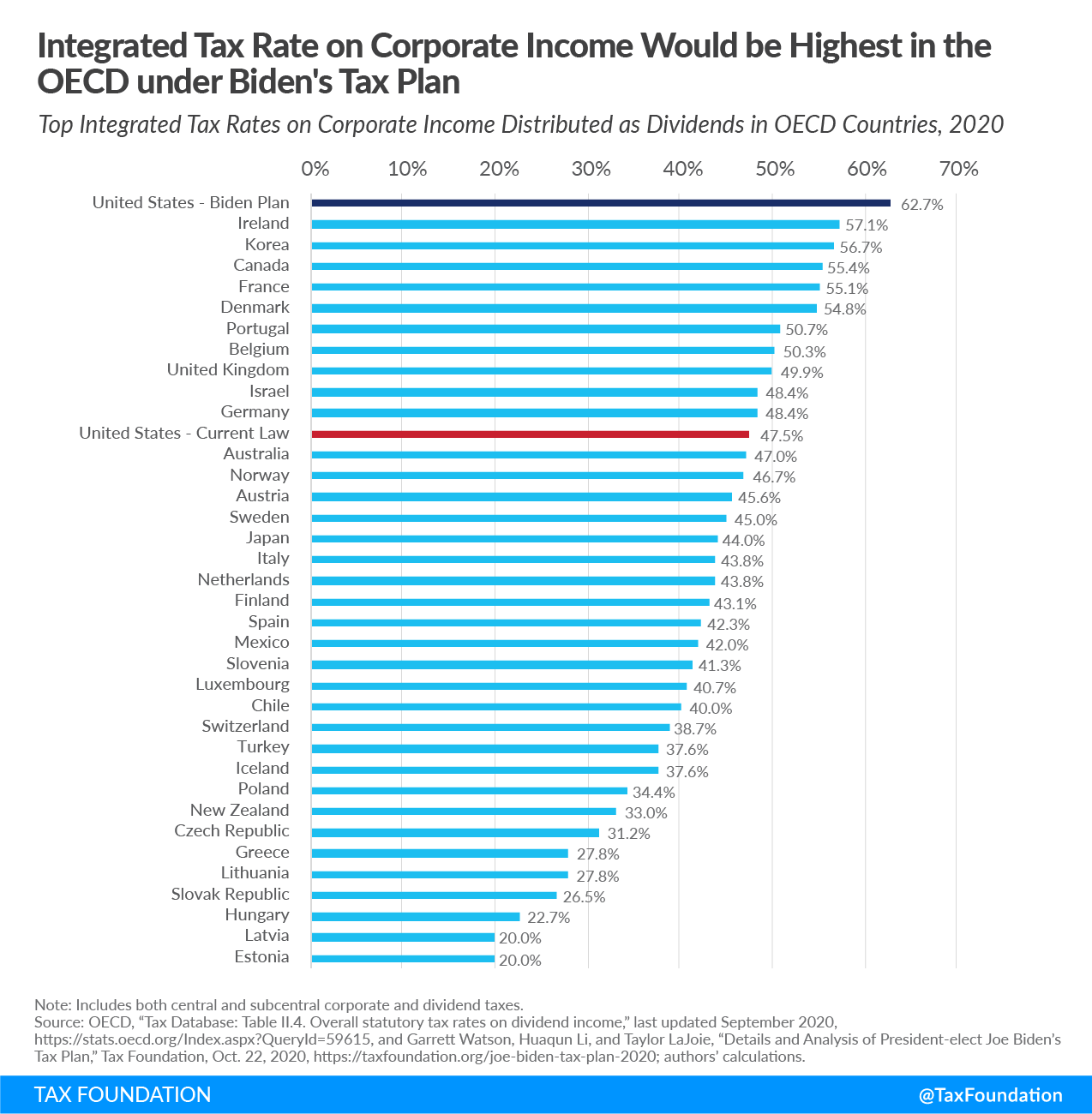

- Joe Biden’s proposal to increase the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate and to tax long-term capital gains and qualified dividends at ordinary income rates would increase the top integrated tax rate on distributed dividends to 62.73 percent, highest in the OECD.

- Income earned in the U.S. through a pass-through businessA pass-through business is a sole proprietorship, partnership, or S corporation that is not subject to the corporate income tax; instead, this business reports its income on the individual income tax returns of the owners and is taxed at individual income tax rates. is taxed at an average top combined statutory rate of 45.9 percent.

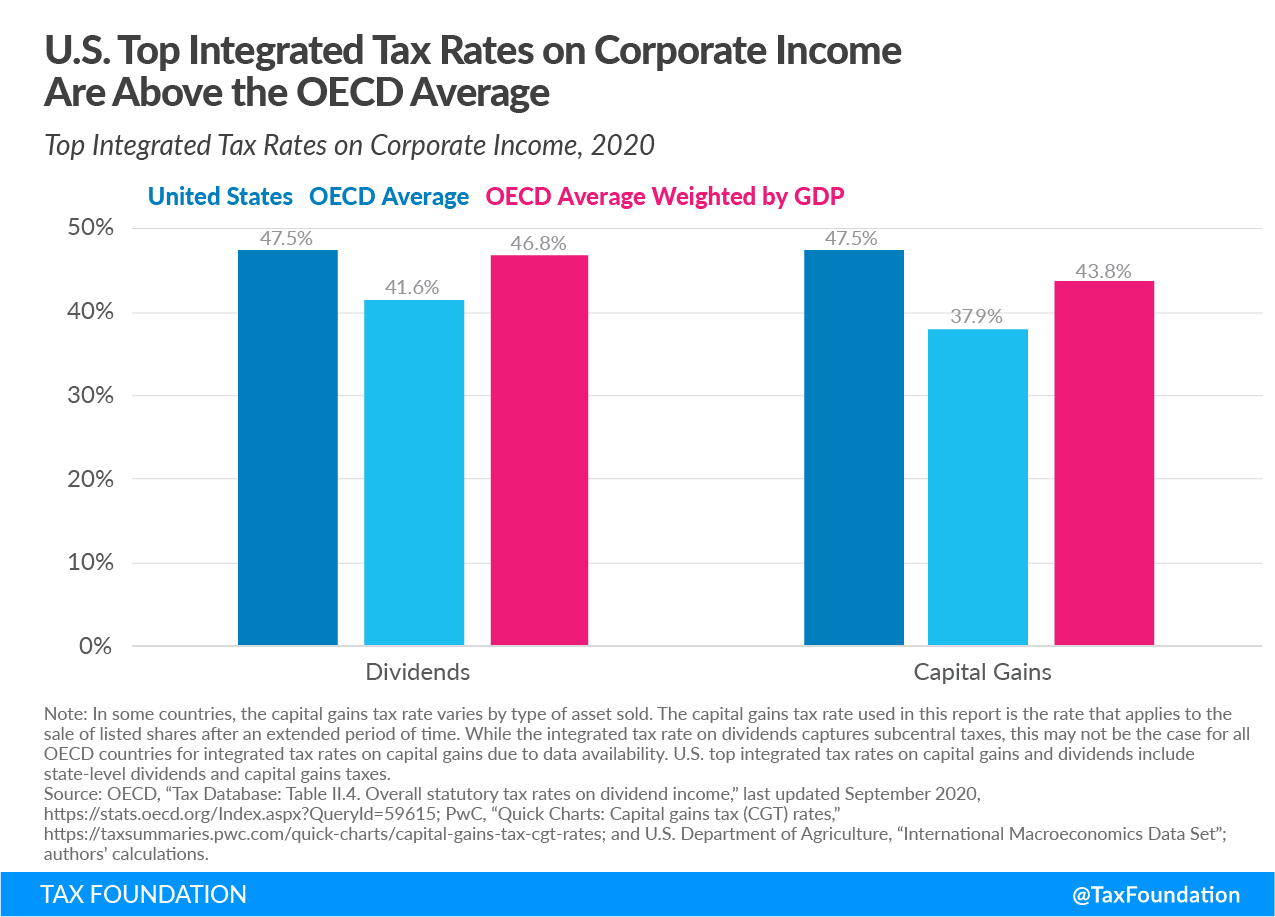

- On average, OECD countries tax corporate income distributed as dividends at 41.6 percent and capital gains derived from corporate income[1] at 37.9 percent.

- Double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. of corporate income can lead to such economic distortions as reduced savings and investment, a bias towards certain business forms, and debt financing over equity financing.

- Several OECD countries have integrated corporate and individual tax codes to eliminate or reduce the negative effects of double taxation on corporate income.

Introduction

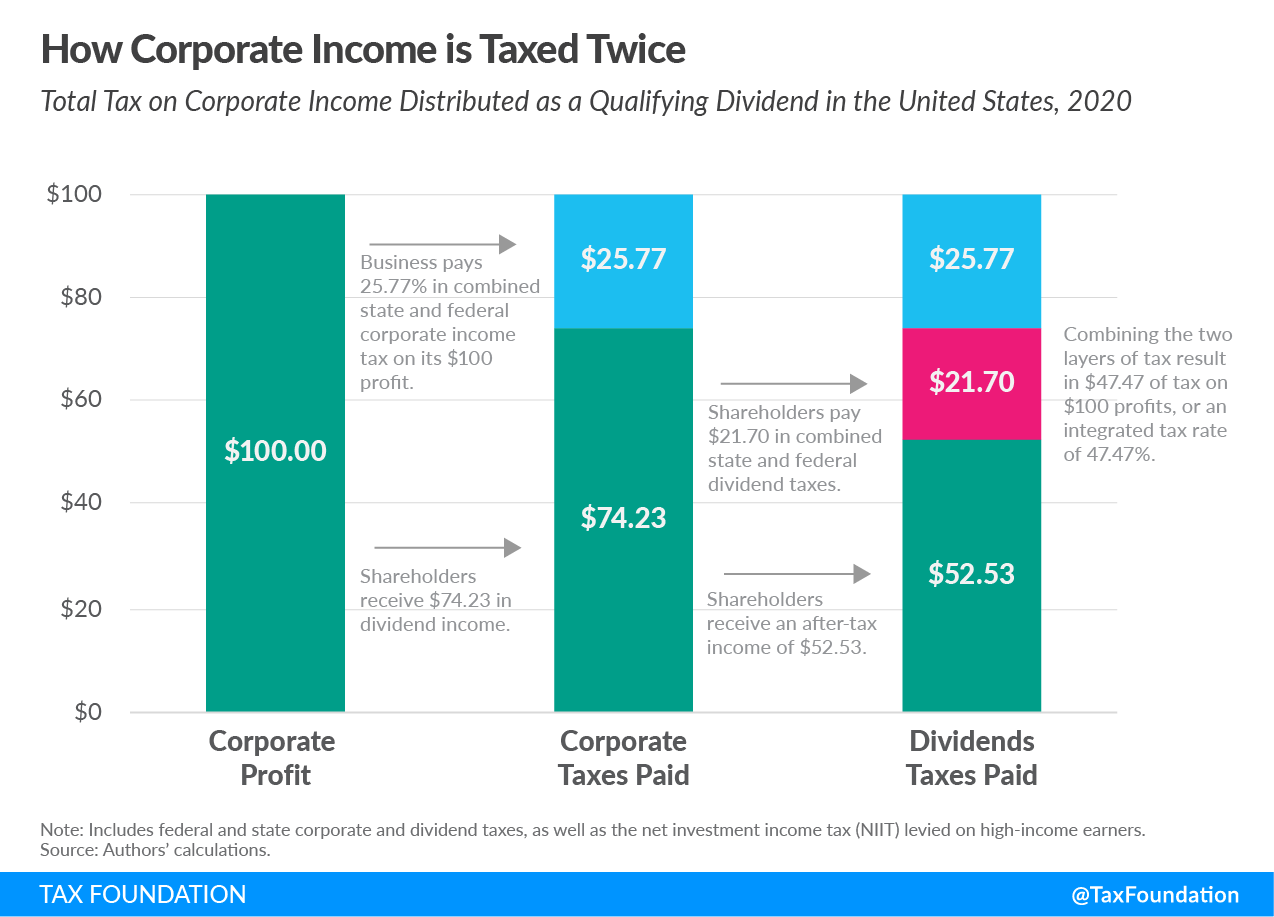

In the United States, corporate income is taxed twice, once at the entity level and once at the shareholder level. Before shareholders pay taxes, the business first faces the corporate income tax. A business pays corporate income tax on its profits; thus, when the shareholder pays their layer of tax they are doing so on dividends or capital gains distributed from after-tax profits.

The integrated tax rate on corporate income reflects both the corporate income tax and the dividends or capital gains taxA capital gains tax is levied on the profit made from selling an asset and is often in addition to corporate income taxes, frequently resulting in double taxation. These taxes create a bias against saving, leading to a lower level of national income by encouraging present consumption over investment. —the total tax levied on corporate income. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) significantly reduced the tax burden on corporate income in the United States, which brought the U.S. integrated tax rate on corporate income closer to the OECD average and thus improved U.S. competitiveness.[2]

Double Taxation of Corporate Income in the United States

Under current law, income earned by C corporations in the United States is taxed at the entity level at a statutory federal rate of 21 percent, plus state corporate taxes. After paying the corporate income tax, the firm can either distribute its after-tax profits to shareholders through dividend payments or reinvest or hold its after-tax earnings, which raises the value of its stock and leads to capital gains.

If the corporation distributes dividends, those are taxed at the shareholder level as high as 37 percent under the federal individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. rate for ordinary dividends or as high as 20 percent for qualified dividends[3] (plus the 3.8 percent net income investment tax [NIIT] for certain high-income taxpayers). States levy additional taxes on dividends.

Investors also pay tax when stock appreciates and is sold for a gain. Capital gains tax rates vary with respect to two factors: how long the asset was held and the amount of income the taxpayer earns. However, capital gains are not considered taxable income until they are realized (when the asset is sold), allowing investors to defer tax on their gains until realization.

As an example, suppose that a corporation earns $100 of profit in 2020. It must pay corporate income tax of $25.77 (federal and state combined rate of 25.77 percent), which leaves the corporation with $74.23 in after-tax profits. If the corporation distributes those earnings as a dividend, the income is taxed again at the individual level at a top rate of 29.23 percent (federal and state combined tax rate on qualified dividends [including NIIT], resulting in $21.70 in federal and state income taxes. Thus, final after-tax income is $52.53, implying that the $100 in original corporate profits faces an integrated tax rate on corporate income of 47.47 percent.

Integrated Tax Rates on Corporate Income and the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

The TCJA significantly lowered the integrated tax rate on corporate income, largely due to the significant cut in the federal corporate income tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent. In 2017, the last year before the TCJA went into effect, the top integrated tax rate on corporate income distributed as dividends was 56.33 percent. In 2020, the top integrated rate stands at 47.47 percent, approximately 9 percentage points lower than pre-TCJA.

| Pre-TCJA (2017) | Current Law (2020) | |

|---|---|---|

| Corporate Profits | $100 | $100 |

| Corporate Income Tax (Combined Federal and State Statutory Corporate Rate) | -$38.91 | -$25.77 |

| Distributed Dividends | $61.09 | $74.23 |

| Dividend Income Tax (Combined Federal and State Statutory Rate on Qualified Dividends) | -$17.42 | -$21.70 |

| Total After-Tax Income | $43.67 | $52.53 |

| Integrated Tax Rate | 56.33% | 47.47% |

|

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on OECD, “Tax Database: Table II.4. Overall statutory tax rates on dividend income,” last updated September 2020, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?QueryId=59615. |

||

Integrated Tax Rates on Corporate Income versus Pass-through Income

Pass-through businesses, such as sole proprietorships, S corporations, and partnerships, make up the majority of businesses in the United States. At the federal level and in most states, the income of these pass-through businesses is only subject to individual income tax, and thus does not face corporate taxes.[4] In other words, pass-through business earnings are “passed through” to their owners, who pay ordinary individual income tax on them.

The marginal tax rates vary for pass-through firms depending on the state where they operate, as states tax individual income differently.[5] Income earned by a pass-through business is taxed at an average top rate of 45.9 percent, 1.6 percentage points lower than traditional C corporations.

| Traditional C Corporations | Pass-through Businesses | |

|---|---|---|

| Entity-Level Tax | 25.8% | 0.0% |

| Individual-Level Tax | 29.2% | 45.9% |

| Total Tax Rate | 47.5% | 45.9% |

|

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on Garrett Watson, “Marginal Tax Rates for Pass-through Businesses by State,” Tax Foundation, July 15, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/pass-through-businesses-tax-rate-2020/. Note: Example assumes C corporation distributes dividends. Pass-through business is a partnership. Top marginal tax rates on pass-through income vary by state. The pass-through tax rate shown here is the U.S. average combined federal and state top marginal tax rate as of January 1, 2020. |

||

Qualifying pass-through firms may use Section 199A, commonly known as the pass-through deduction, to deduct 20 percent of their qualified business income from federal income tax. However, the pass-through deduction is subject to limitations for firms earning above certain income limits that operate in a “specified service trade or business” (SSTB) and other guardrails that limit the size of the deduction. This means that many pass throughs are not eligible for Section 199A and face top marginal income tax rates without it.

Integrated Tax Rates on Corporate Income under Biden’s Tax Plan

President Joe Biden’s tax plan includes various federal tax changes.[6] The following tax changes would directly[7] impact the top statutory integrated tax rate on corporate income:

- Increase in the statutory federal corporate income tax rate from 21 percent to 28 percent.

- Taxing long-term capital gains and qualified dividends at the ordinary income tax rate of 39.6 percent on income above $1 million.

| Current Law (2020) | Biden Plan | |

|---|---|---|

| Corporate Profits | $100 | $100 |

| Corporate Income Tax (Combined Federal and State Statutory Corporate Rate) | -$25.77 | -$32.20 |

| Distributed Dividends | $74.23 | $67.80 |

| Dividend Income Tax (Combined Federal and State Statutory Rate on Qualified Dividends) | -$21.70 | -$30.53 |

| Total After-Tax Income | $52.53 | $37.27 |

| Integrated Tax Rate | 47.47% | 62.73% |

|

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on OECD, “Tax Database: Table II.4. Overall statutory tax rates on dividend income,” last updated September 2020, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?QueryId=59615, and Garrett Watson, Huaqun Li, and Taylor LaJoie, “Details and Analysis of President Joe Biden’s Tax Plan,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 22, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/joe-biden-tax-plan-2020. Note: The calculations for Biden’s tax plan assume a 28 percent federal corporate income tax rate (32.2 percent if state corporate taxes are included) and a 39.6 percent ordinary federal individual income tax rate (45.0 percent including state taxes on dividends). |

||

Taking these two changes into account, the top integrated tax rate on distributed dividends increases from 47.47 percent under current law to 62.73 percent, which would be higher than pre-TCJA and the highest in the OECD.[8]

Integrated Tax Rates on Corporate Income in the OECD

Most OECD countries—like the United States—double-tax corporate income by taxing it at the entity and at the shareholder levels. On average, OECD countries tax corporate income distributed as dividends at a rate of 41.6 percent (46.8 percent if weighted by GDP) and capital gains derived from corporate income[9] at 37.9 percent (43.8 percent weighted by GDP). At 47.5 percent, the U.S. top integrated tax rates are above the OECD average for both dividends and capital gains.

For dividends, Ireland’s top integrated tax rate was highest in the OECD, at 57.1 percent, followed by South Korea (56.7 percent) and Canada (55.4 percent). Estonia (20 percent), Latvia (20 percent), and Hungary (22.7 percent) levy the lowest rates. Estonia and Latvia’s dividend exemption system means that the corporate income tax is the only layer of taxation on corporate income distributed as dividends.

For capital gains,[10] Chile (55 percent), Denmark (54.8 percent), and France (52.4 percent) have the highest integrated rates in the OECD, while the Czech Republic (19 percent), Slovenia (19 percent), and Slovakia (21 percent) levy the lowest rates. Several OECD countries—namely Belgium, the Czech Republic, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Korea, Switzerland, and Turkey—do not levy capital gains taxes on long-term capital gains, making the corporate tax the only layer of tax on corporate income realized as long-term capital gains.

Distortions Created by the Double Taxation of Corporate Income

The interaction of entity and shareholder level taxes on corporate income has significant implications on both business decisions and the overall economy.

Reduced Investment

A higher marginal tax rateThe marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. on both corporate income and investment income makes investments more costly, reducing the number of projects corporations invest in. This leads to lower levels of investment and a smaller capital stock in the overall economy. A smaller capital stock means lower worker productivity, lower wages, and slower economic growth.

Shift to Non-corporate Business Forms

The double tax on corporate income can also distort the organizational form of businesses. Unlike traditional C corporations, pass-through businesses, such as S corporations, partnerships, and sole proprietorships, only face one layer of tax, as there is no entity level tax (at the federal level and in most states). All profits from these entities are immediately passed through to their owners, who pay the individual income tax.

The reduction in the corporate tax rate enacted through the TCJA has largely aligned the tax rate on corporate income and pass-through income that does not qualify for the Section 199A deduction. However, businesses that do qualify for the Section 199A deduction face a lower tax rate than C corporations, creating a bias towards pass-through businesses.

Debt over Equity

When a corporation wants to fund a new project, it can either finance it through equity (issue of new shares or use of retained earnings) or it can borrow money. The current tax code treats debt financing more favorably than equity financing. Specifically, there are two layers of taxation on equity financing and only one layer of taxation on debt financing, due to the deduction for net interest expense.

Suppose a corporation issues new stock to raise money to purchase a machine. When this investment earns a profit, the corporation needs to pay the corporate income tax. It then needs to compensate the original investors, so the corporation distributes the after-tax earnings as dividends. The investors then need to pay tax on these dividends. This equity-financed project nets two layers of tax, one at the corporate level and one at the shareholder level.

Alternatively, the corporation could finance the same investment by borrowing money. When the corporation earns a profit from a debt-financed investment, it needs to pay the corporate income tax on its profits. But before the corporation pays its corporate tax, it needs to pay its lender back a portion of what it borrowed plus interest. Under current law, corporations can deduct interest payments they make to lenders against their taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. . Thus, profits derived from the debt-financed investment do not face a corporate level tax on the portion of the profit that is paid back in interest. The lender then receives the interest as income and needs to pay tax on it. The debt-financed project only nets a single layer of tax at the debt holder’s level.

Due to this inequitable treatment of debt and equity in the tax code, the rate of return on debt-financed projects, all else equal, is higher. This encourages corporations to borrow more than they otherwise would in the absence of the double tax on equity investment.[11]

Corporate Integration

Corporate integration standardizes the taxation of business income across business forms and methods of financing by integrating the corporate and individual tax codes. There are many ways in which corporate integration can be designed. Australia and Estonia provide examples for credit imputation and dividend exemption systems, respectively.

Australia

Australia integrates their corporate and individual income taxes with a tax credit imputation. Both the corporation and the shareholder pay part of the corporate income tax, but the shareholder is given a tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. to offset the taxes already paid by the corporation. In the end, corporate income is taxed at the marginal income tax rate applied to its shareholders.

Estonia

Estonia integrates its corporate and individual income tax code by having a full dividend exemption at the shareholder level. This system of integration levies only one layer of tax on corporate income at the corporate level when dividends are distributed. When the shareholder receives dividends from the corporation, there is no additional tax due.[12]

Conclusion

The U.S. tax code—as with many OECD countries’ tax systems—double-taxes corporate income: once at the corporate level and then again at the shareholder level. This creates a significant tax burden on corporate income, which increases the cost of investment, encourages a shift from the traditional C corporate form, and incentivizes debt financing.

The TCJA significantly lowered the integrated tax rate on corporate income in the United States. Biden’s proposal to increase the corporate income tax rate and to tax long-term capital gains and qualified dividends at ordinary income tax rates would increase the top integrated tax rate above pre-TCJA levels, making it the highest in the OECD and undercutting American economic competitiveness.

Appendix

| Top Integrated Tax Rates on Corporate Income in OECD Countries, 2020 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OECD Country | Statutory Corporate Income Tax Rate | Dividends | Capital Gains (a) | ||

| Top Personal Dividend Tax Rate | Integrated Tax on Corporate Income (Dividends) | Top Personal Capital Gains Tax Rate | Integrated Tax on Corporate Income (Capital Gains) | ||

| Australia | 30.0% | 24.3% | 47.0% | 23.5% | 46.5% |

| Austria | 25.0% | 27.5% | 45.6% | 27.5% | 45.6% |

| Belgium | 29.0% | 30.0% | 50.3% | 0.0% | 29.0% |

| Canada | 26.4% | 39.3% | 55.4% | 26.3% | 45.7% |

| Chile | 25.0% | 20.0% | 40.0% | 40.0% | 55.0% |

| Czech Republic | 19.0% | 15.0% | 31.2% | 0.0% | 19.0% |

| Denmark | 22.0% | 42.0% | 54.8% | 42.0% | 54.8% |

| Estonia | 20.0% | 0.0% | 20.0% | 20.0% | 36.0% |

| Finland | 20.0% | 28.9% | 43.1% | 34.0% | 47.2% |

| France | 32.0% | 34.0% | 55.1% | 30.0% | 52.4% |

| Germany | 29.9% | 26.4% | 48.4% | 26.4% | 48.4% |

| Greece | 24.0% | 5.0% | 27.8% | 15.0% | 35.4% |

| Hungary | 9.0% | 15.0% | 22.7% | 15.0% | 22.7% |

| Iceland | 20.0% | 22.0% | 37.6% | 22.0% | 37.6% |

| Ireland | 12.5% | 51.0% | 57.1% | 33.0% | 41.4% |

| Israel | 23.0% | 33.0% | 48.4% | 25.0% | 42.3% |

| Italy | 24.0% | 26.0% | 43.8% | 26.0% | 43.8% |

| Japan | 29.7% | 20.3% | 44.0% | 20.4% | 44.1% |

| Korea | 27.5% | 40.3% | 56.7% | 0.0% | 27.5% |

| Latvia | 20.0% | 0.0% | 20.0% | 20.0% | 36.0% |

| Lithuania | 15.0% | 15.0% | 27.8% | 20.0% | 32.0% |

| Luxembourg | 24.9% | 21.0% | 40.7% | 0.0% | 24.9% |

| Mexico | 30.0% | 17.1% | 42.0% | 10.0% | 37.0% |

| Netherlands (b) | 25.0% | 25.0% | 43.8% | 30.0% | 47.5% |

| New Zealand | 28.0% | 6.9% | 33.0% | 0.0% | 28.0% |

| Norway | 22.0% | 31.7% | 46.7% | 31.7% | 46.7% |

| Poland | 19.0% | 19.0% | 34.4% | 19.0% | 34.4% |

| Portugal | 31.5% | 28.0% | 50.7% | 28.0% | 50.7% |

| Slovak Republic | 21.0% | 7.0% | 26.5% | 0.0% | 21.0% |

| Slovenia | 19.0% | 27.5% | 41.3% | 0.0% | 19.0% |

| Spain | 25.0% | 23.0% | 42.3% | 23.0% | 42.3% |

| Sweden | 21.4% | 30.0% | 45.0% | 30.0% | 45.0% |

| Switzerland | 21.1% | 22.3% | 38.7% | 0.0% | 21.1% |

| Turkey | 22.0% | 20.0% | 37.6% | 0.0% | 22.0% |

| United Kingdom | 19.0% | 38.1% | 49.9% | 20.0% | 35.2% |

| United States (c) | 25.8% | 29.2% | 47.5% | 29.2% | 47.5% |

| Average | 23.3% | 23.9% | 41.6% | 19.1% | 37.9% |

|

Source: OECD, “Tax Database: Table II.4. Overall statutory tax rates on dividend income,” last updated September 2020, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?QueryId=59615; PwC, “Quick Charts: Capital gains tax (CGT) rates,” https://taxsummaries.pwc.com/quick-charts/capital-gains-tax-cgt-rates; authors’ calculations. Notes: Integrated tax rates are calculated as follows: (Corporate Income Tax) + [(Distributed Profit – Corporate Income Tax) * Dividends or Capital Gains Tax]. (a) In some countries, the capital gains tax rate varies by type of asset sold. The capital gains tax rate used in this report is the rate that applies to the sale of listed shares after an extended period of time. While the integrated tax rate on dividends captures subcentral taxes, this may not be the case for all integrated tax rates on capital gains due to data availability. (b) In the Netherlands, the net asset value is taxed at a flat rate on a deemed annual return. (c) The integrated top tax rate on corporate income distributed as dividends or as capital gains includes both federal and state dividend and capital gains taxes. For state capital gains tax rates, the weighted average of state dividend tax rates (5.4 percent) provided by the OECD was used, as all except one state taxed capital gains the same as dividends in 2020. (New Hampshire imposes a tax on dividends but not on capital gains.) |

|||||

[1] In some countries, the capital gains tax rate varies by type of asset sold. The capital gains tax rate used in this report is the rate that applies to the sale of listed shares after an extended period of time. While the integrated tax rate on dividends captures subcentral taxes, this may not be the case for all integrated tax rates on capital gains due to data availability. The U.S. integrated tax rate on capital gains captures both federal and state taxes.

[2] Robert Bellafiore, “The Lowered Corporate Income Tax Rate Makes the U.S. More Competitive Abroad,” Tax Foundation, May 2, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/lower-us-corporate-income-tax-rate-competitive/.

[3] Unless otherwise noted, this report focuses on the tax levied on qualified rather than ordinary dividends. Whereas ordinary dividends are taxable as ordinary income, qualified dividends that meet certain requirements are taxed at the lower capital gain rates (e.g., long-term capital gains held for more than one year). See Internal Revenue Service (IRS), “Topic No. 404 Dividends,” https://www.irs.gov/taxtopics/tc404.

[4] Wolters Kluwer, ”State Entity-Level Tax on Pass-Through Entities,” Jan. 24, 2019, http://news.cchgroup.com/2019/01/24/state-entity-level-tax-on-pass-through-entities/news/state-tax-headlines/.

[5] For pass-through tax rates by state, see Garrett Watson, “Marginal Tax Rates for Pass-through Businesses by State,” Tax Foundation, July 15, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/pass-through-businesses-tax-rate-2020/. The average U.S. pass-through tax rate shown in this report represents the simple average of all U.S. states’ combined federal and state top marginal tax rates as of January 1, 2020.

[6] A detailed overview and economic and distributional analysis of Biden’s tax plan can be found in Garrett Watson, Huaqun Li, and Taylor LaJoie, “Details and Analysis of President Joe Biden’s Tax Plan,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 22, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/joe-biden-tax-plan-2020.

[7] Biden’s plan also includes restoring the Pease limitation on itemized deductions for taxable incomes above $400,000, which, combined with changes to the state and local tax (SALT) deduction, would change marginal and average effective tax rates. (It would not, however, impact the top statutory rate.) See Jared Walczak, “Top Rates in Each State Under Joe Biden’s Tax Plan,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 20, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/top-tax-rates-under-biden-tax-plan/.

[8] For long-term capital gains, the federal integrated tax rate would increase from 43.4 percent to 59.05 percent. This, however, does not include state-level capital gains taxes (each state taxes capital gains differently). The integrated top tax rate on corporate income distributed as dividends includes both federal and state dividend taxes.

[9] In some countries, the capital gains tax rate varies by type of asset sold. The capital gains tax rate used in this report is the rate that applies to the sale of listed shares after an extended period of time. Some OECD countries’ integrated tax rates on capital gains may not include taxes levied at the subcentral level due to data availability. U.S. top integrated tax rates on capital gains include state-level capital gains taxes.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Under the TCJA, the deduction for net interest expense is generally limited to 30 percent of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) through 2021, and thereafter limited to 30 percent of earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT). Although limiting interest deductions has narrowed the debt-bias embedded in the tax code, it has not eliminated it.

[12] More details on the trade-offs between the different forms of corporate integration can be found in Scott Greenberg, “Corporate Integration: An Important Component of Tax Reform,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 21, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/corporate-integration-important-component-tax-reform.

Share this article