TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. Day is here, and if you’ve already filed your federal and state income tax returns, you’re probably relieved to check that off your to-do list until next year. For most Americans, income tax filing is a time-consuming, resource-intensive, and tedious process. According to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), this tax season, nonbusiness individual income taxpayers will spend an average of 8 hours and $160 filing their federal tax returns, while owners of pass-through businesses will spend an average of 24 hours and $620 to file. When state (and sometimes even local) filing is required, the costs of compliance can grow much higher. And for taxpayers who are required to file resident and nonresident tax returns in multiple states (and even multiple localities), the complexity can be enough to intimidate even paid tax preparers.

Some taxpayers respond to exceedingly complex tax laws by cutting corners, while many unknowingly make mistakes due to a lack of tax expertise. One area of the tax code in which extreme complexity and low compliance go hand-in-hand—and where reform is desperately needed—is in states’ nonresident individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. filing and withholdingWithholding is the income an employer takes out of an employee’s paycheck and remits to the federal, state, and/or local government. It is calculated based on the amount of income earned, the taxpayer’s filing status, the number of allowances claimed, and any additional amount the employee requests. laws.

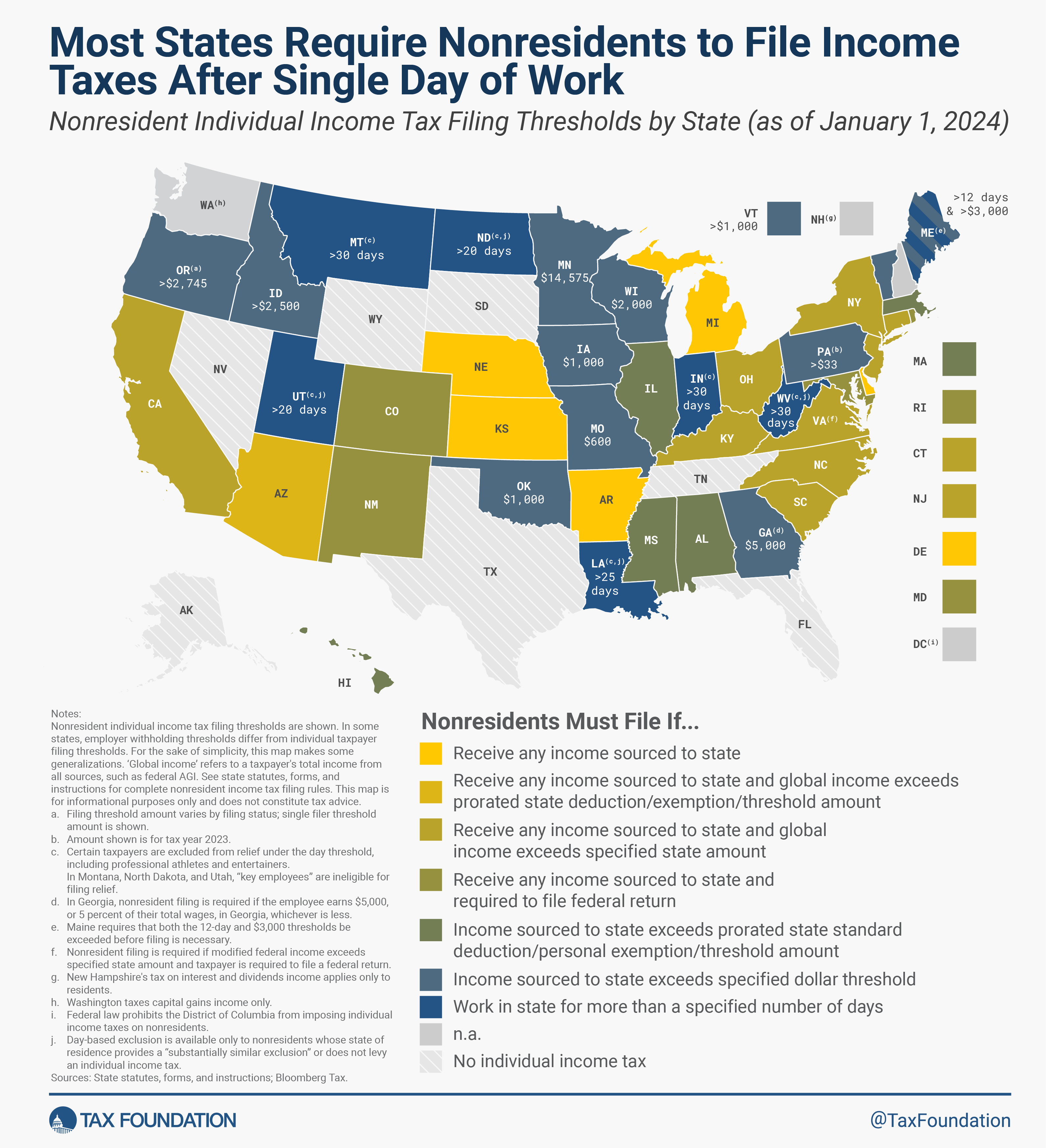

States’ Nonresident Individual Income Tax Filing Thresholds

As of January 1, 2025, 23 states have no meaningful nonresident individual income tax filing threshold, meaning most nonresidents are required to file an individual income tax return if they spend even a single day working in the state. Meanwhile, 18 states have nonresident individual income tax filing thresholds that relieve nonresidents from filing obligations when they perform limited work in the state. Of these, seven states’ thresholds are based on days spent in the state, ranging from 20 days (with a mutuality requirement, explained later) in North Dakota to 30 days (with no mutuality requirement) in Illinois, Indiana, and Montana.

Nine states’ thresholds are based on the amount of income earned in the state, ranging from $100 in Vermont to $14,950 in Minnesota. Two states, Connecticut and Maine, require nonresidents to file only if they spend a certain number of days in the state and earn a certain amount of income in the state. For example, in Connecticut, nonresidents are required to file only after they work for more than 15 days and earn more than $6,000 in the state. Finally, nine states do not levy an individual income tax on wage and salary income at all, while federal law prohibits the District of Columbia from applying its individual income tax to nonresidents.

Nonresident Income Tax Filing by State

Nonresident Individual Income Tax Filing and Withholding Thresholds as of January 1, 2025

| State | Filing Threshold | Withholding Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 1 day | 1 day |

| Alaska | n.a. | n.a. |

| Arizona | 1 day | 60 days |

| Arkansas | 1 day | 1 day |

| California | 1 day | > $1,500 |

| Colorado | 1 day | 1 day |

| Connecticut | > 15 days and > $6,000 | > 15 days |

| Delaware | 1 day | 1 day |

| Florida | n.a. | n.a. |

| Georgia | $5,000 or 5% of wages | > 23 days or > $5,000 or > 5% of wages |

| Hawaii | 1 day | > 60 days |

| Idaho | > $2,500 | $1,000 |

| Illinois | 1 day | > 30 days |

| Indiana | > 30 days | > 30 days |

| Iowa | $1,000 | 1 day |

| Kansas | 1 day | 1 day |

| Kentucky | 1 day | 1 day |

| Louisiana | > 25 days (a) | > 25 days (a) |

| Maine | > 12 days and > $3,000 | > 12 days and > $3,000 |

| Maryland | 1 day | 1 day |

| Massachusetts | 1 day | 1 day |

| Michigan | 1 day | 1 day |

| Minnesota | $14,950 (MN sources) (b) | $14,950 (all sources) (b) |

| Mississippi | 1 day | 1 day |

| Missouri | $600 | 1 day |

| Montana | > 30 days | > 30 days |

| Nebraska | 1 day | 1 day |

| Nevada | n.a. | n.a. |

| New Hampshire | n.a. | n.a. |

| New Jersey | 1 day | 1 day |

| New Mexico | 1 day | > 15 days |

| New York | 1 day | > 14 days |

| North Carolina | 1 day | 1 day |

| North Dakota | > 20 days (a) | > 20 days (a) |

| Ohio | 1 day | $300 quarterly |

| Oklahoma | $1,000 | > $300 quarterly |

| Oregon | > $2,800 (b)(c) | 1 day |

| Pennsylvania | 1 day | 1 day |

| Rhode Island | 1 day | 1 day |

| South Carolina | 1 day | > $2,000 |

| South Dakota | n.a. | n.a. |

| Tennessee | n.a. | n.a. |

| Texas | n.a. | n.a. |

| Utah | > 20 days (a) | > 20 days (a) |

| Vermont | > $100 | 30 days |

| Virginia | 1 day | 1 day |

| Washington | n.a. | n.a. |

| West Virginia | > 30 days (a) | > 30 days (a) |

| Wisconsin | $2,000 | $2,000 |

| Wyoming | n.a. | n.a. |

| District of Columbia | n.a. (d) | n.a. (d) |

(b) Threshold is adjusted annually for inflation.

(c) Threshold varies by filing status; single filer amount is shown.

(d) Federal law prohibits the District of Columbia from taxing nonresidents' income.

Source: Tax Foundation; Bloomberg Tax; state statutes.

Data compiled by Katherine Loughead

Credits for Taxes Paid to Other States

Individuals who reside in a state with an income tax can claim a credit from their home state for income taxes paid to other states, so while paying income taxes to other states does not necessarily increase an individual’s total state tax liability (this depends on whether the other state has higher rates on that income), it does substantially increase the complexity and costs associated with filing. Since states have the authority to tax individuals where they live and where they work, it is relatively common for more than one state to stake a legitimate claim to the same share of a taxpayer’s income. Credits for taxes paid to other states are therefore critical to prevent double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. .

Mutuality Requirements

In some states with day-based thresholds, those thresholds do not apply to everyone. Currently, four of the six states with day-based filing thresholds—Louisiana, North Dakota, Utah, and West Virginia—have a “mutuality requirement” that extends filing relief only to nonresidents who live in a state that does not levy an individual income tax or that offers a “substantially similar” exclusion. For example, in general, a resident of Indiana who works in Utah for 20 days or fewer is not required to file a nonresident tax return in Utah, since Indiana has a similar nonresident filing threshold. However, since Colorado does not have a meaningful filing threshold, a resident of Colorado who spends even a single day working in Utah is not eligible for Utah’s safe harbor and is therefore required to file on day one. Since “substantially similar exclusion” is not clearly defined in regulations, taxpayers can be left in the dark on whether their own state’s provisions are adequate.

Illinois, Indiana, and Montana, which all have 30-day thresholds, are currently the only states that have day-based thresholds that apply broadly to nonresidents regardless of which state they hail from. Forgoing mutuality requirements is the simpler and more neutral approach, as doing so relieves compliance burdens for more individuals and businesses and treats nonresidents neutrally, regardless of the decisions made by policymakers in the states in which they reside.

Filing on Day One

In states that require nonresidents to file for a single day of work in the state, the costs of compliance are often much higher than the amount of taxes remitted. There are many situations in which a taxpayer might owe only a few dollars—or even nothing at all—to a state but still face a legal obligation to file, which can cost $59 or more using popular tax filing software. This can add up quickly for those who travel frequently for work, especially those who visit many different states and municipalities while spending only a short time in each.

Additionally, a nonresident’s low- or zero-dollar income tax return can easily cost a state more to process than is remitted with the return. In practice, revenue departments are typically much more concerned about the compliance of high-income earners (such as professional athletes and entertainers) than of average taxpayers. Unless an employer adjusts an individual’s withholding to the nonresident state, revenue departments oftentimes do not know (or cannot prove) that an individual spent time working in the state without filing a return. Ultimately, keeping laws on the books that are unenforceable or are not worth enforcing is bad tax policy, especially to the extent those policies generate little revenue while creating steep compliance burdens for the honest taxpayers who try to comply.

Nonresident Filing and Withholding Thresholds Oftentimes Do Not Match

Within the same state, nonresident filing and withholding thresholds often differ. For example, employers are only required to withhold on behalf of nonresident employees who spend 60 days or more working in Arizona, but those nonresident employees are required to file when they work even a single day in Arizona. In cases such as these, many individuals assume they are not required to file if their employer does not withhold, but this is frequently not the case. For more information about states’ nonresident income tax withholding thresholds, see our nonresident income tax primer.

Local Income Taxes Too?

Adding to the complexity, 14 states—Alabama, Colorado, Delaware, Indiana, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia—have local income taxes that sometimes apply to nonresidents, increasing the costs of compliance even further, especially for those spending only a short time working in any given city or county. Ultimately, more states should consider moving away from local income taxes altogether or avoid applying them to nonresidents (as is the case in Kansas and Kentucky).

Opportunities for Reform

At the federal level, the Mobile Workforce State Income Tax Simplification Act has been repeatedly introduced to establish a uniform 30-day nonresident individual income tax filing and withhold threshold across the states. But unless Congress acts, taxpayers will be forced to continue to comply with a complex patchwork of states’ nonresident income tax filing and withholding laws.

This leaves state policymakers with an opportunity to take the initiative to adopt state-level reforms that reduce complexity and compliance costs for individuals and employers and streamline administrative and enforcement costs for the state. More states should consider following in the footsteps of Illinois, Indiana, and Montana, adopting 30-day filing and withholding thresholds, which many stakeholders agree strike an appropriate balance between reducing compliance burdens and allocating nonresident income tax revenue to states in which a substantial amount of work is performed by nonresidents. If most states proactively adopted meaningful nonresident individual income tax filing and withholding thresholds, the state income tax landscape would become substantially less burdensome for America’s increasingly mobile workforce.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe