Forty-three states adopted tax relief in 2021 or 2022—often in both years—and of those, 21 cut state income taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. rates. It’s been a remarkable trend, driven by robust state revenues and an increasingly competitive tax environment. But many observers doubted the trend could, or should, continue into 2023.

It can. It should. It will.

Lawmakers in upwards of a dozen states are seriously contemplating individual income tax cuts in 2023. In many states, these proposals would either accelerate or build upon rate reductions adopted in the past two years. But not all. Four newcomers could join the fold—Kansas, North Dakota, Virginia, and West Virginia—which could lead to half the states (and 25 of the 43 that taxed some sort of income) cutting individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. rates in three years.

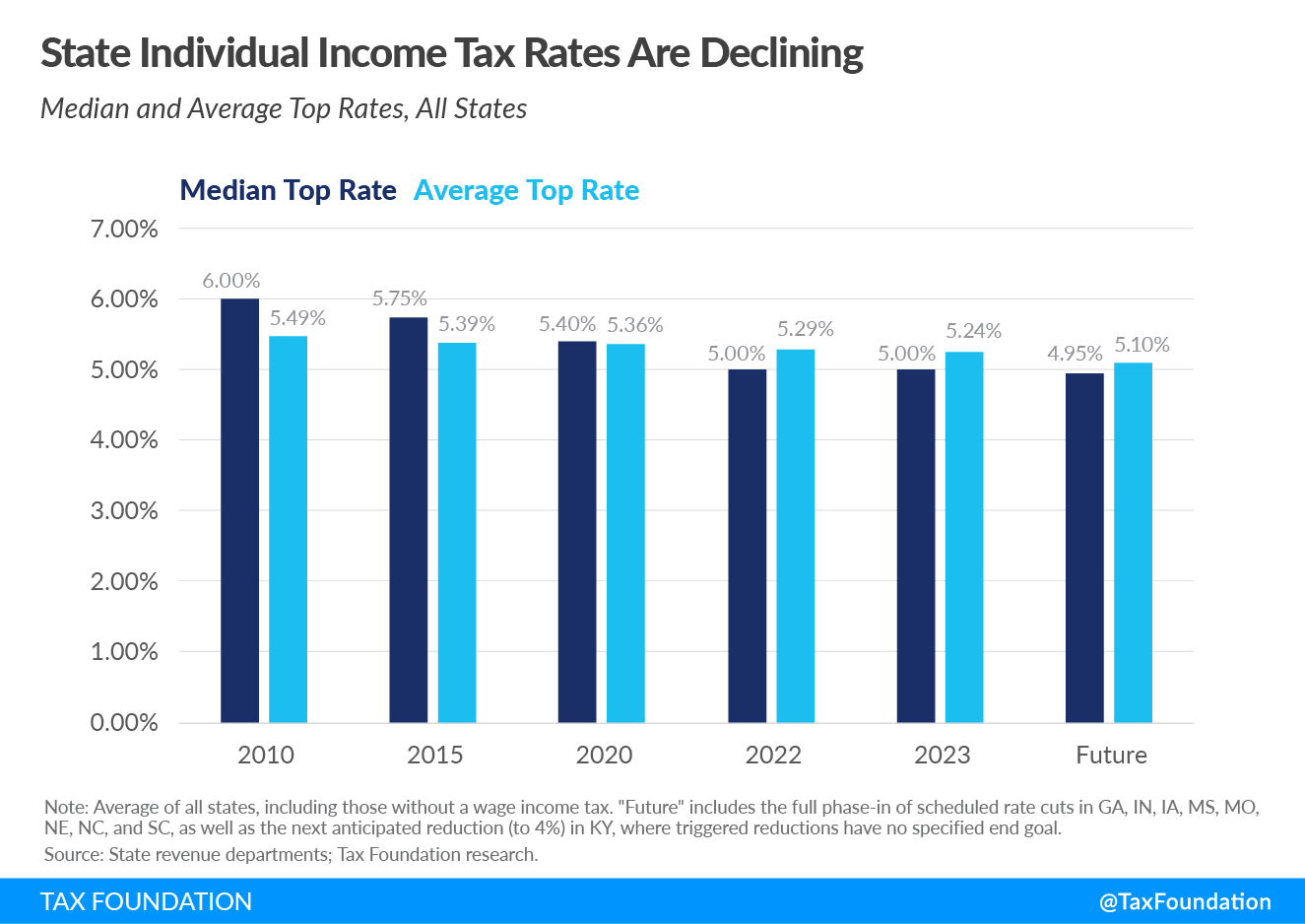

After adjusting for inflation, state tax collections were 9.3 percent higher in 2022 than they were in 2017, even though 17 states had lower top income tax rates in 2022 than they did in 2017, to say nothing of cuts to corporate income taxes and other state taxes. (Four had higher top individual income tax rates in 2017.) The median state’s top individual income tax rate declined from 5.5 percent in 2017 to 5.0 percent in 2022, while tax collections—in real terms—rose 9.3 percent.

These are state tax collections, not state revenues. Federal assistance to state governments during the pandemic is not included in the count. Indirectly, though, the unique circumstances of the pandemic did boost state tax revenues, both because consumer behavior changed—sometimes, but not always, temporarily—and because federal assistance to businesses and individuals increased their taxable activity. States have rightly recognized that some of their own-source revenue gains were temporary and have largely exercised prudence in assessing how much of that growth is sustainable and available to be put toward tax relief.

But it’s a mistake to assume, as some do, that higher tax collections were just a pandemic blip. They were rising long before the pandemic, and experts tend to agree that states have a higher revenue baseline than they did six years ago. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) broadened tax bases (which flowed through to state tax codes) and increased domestic investment. Broad economic changes in recent years have generally yielded higher taxation. And, unfortunately and unfairly, inflation has increased taxability in real, not just nominal, terms.

In other words, most states can afford to provide tax relief. And in an increasingly mobile environment, where people have more flexibility than ever to choose where they live and work, some can hardly afford not to.

And while no one knows if a recession is on the horizon, we do know that states’ revenue baselines are higher than they used to be. Moreover, the states that have forgone tax cuts aren’t sitting on their reserves. They’ve simply chosen to plow their revenue growth into new (often recurring) spending programs rather than returning a portion of it to taxpayers.

In aggregate, the 12 states known to be considering income tax cuts this year—including eight that have already adopted reductions—are anticipating that this coming fiscal year’s tax revenues will be 9.1 percent higher (inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. -adjusted) than pre-pandemic collections. Some, like Utah (32.3 percent), Idaho (24.2 percent), and Arkansas (18.7 percent), are looking at particularly dramatic gains. And if anything, FY 2025 could be better. Some of these states have not yet published their FY 2025 forecasts, but among those that do, the anticipated real tax revenue growth since before the pandemic is 11 percent.

Meanwhile, states’ rainy day funds have never been better stocked, and many states are running large surpluses. Idaho, for instance, is projecting a current-year surplus equivalent to 40 percent of its pre-pandemic annual tax collections.

No wonder income tax relief is on the table in Arkansas, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and potentially elsewhere.

And all the more astonishing that in a different set of states, the tax conversation is about creating new and higher taxes on wealth, investment, and entrepreneurship—tax proposals that seem unrelated to any real or perceived revenue needs, and which tend not to even be connected to new spending proposals. Increasingly, states are offering taxpayers and businesses a choice between jurisdictions that view growing revenues as a reason to cut taxes and double down on their competitive edge, and those that are instead focused on raising taxes, regardless of necessity and with indifference to the economic costs.

After two years of tax reform and tax relief, 2023 appears to be setting states on divergent paths. Their respective choices are only likely to accelerate the migration to, and greater economic growth of, those states that are choosing a more competitive tax environment.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe