Explore Our New Interactive Tool Download Promotional Toolkit

Introduction

The structure of a country’s tax code is an important determinant of its economic performance. A well-structured taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. code is easy for taxpayers to comply with and can promote economic development while raising sufficient revenue for a government’s priorities. In contrast, poorly structured tax systems can be costly, distort economic decision-making, and harm domestic economies.

Many countries have recognized this and have reformed their tax codes. Over the past few decades, marginal tax rates on corporate and individual income have declined significantly across the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Now, most nations raise a significant amount of revenue from broad-based taxes such as payroll taxes and value-added taxes (VAT).[1]

Not all recent changes in tax policy among OECD countries have improved the structure of tax systems; some have made a negative impact. Though some countries like the United States and Belgium have reduced their corporate income tax rates by several percentage points, others, like Korea and Portugal, have increased them. Corporate tax base improvements have been put in place in the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada, while tax bases were made less competitive in Chile and Korea. Several EU countries have recently adopted international tax regulations like Controlled Foreign Corporation rules that can have negative economic impacts.[2] Additionally, while many countries have removed their net wealth taxes in recent decades, Belgium recently adopted a new tax on net wealth.

Some countries consistently adopt policies that worsen the structure of their tax system relative to other OECD countries. Over the last few decades, France has introduced several reforms that have significantly increased marginal tax rates on work, saving, and investment. For example, France recently instituted a corporate income surtaxA surtax is an additional tax levied on top of an already existing business or individual tax and can have a flat or progressive rate structure. Surtaxes are typically enacted to fund a specific program or initiative, whereas revenue from broader-based taxes, like the individual income tax, typically cover a multitude of programs and services. , which joined other distortive taxes such as the financial transactions tax, a tax on net real estate wealth, and an inheritance tax.

Following tax reform in the United States, France now has the highest taxes on corporate income—a combined rate of about 34 percent. Though the central government statutory rate is scheduled to be lowered over the next several years, many more changes are necessary for France to have a competitive tax code.

The variety of approaches to taxation among OECD countries creates a need for a way to evaluate these systems relative to each other. For that purpose, we have developed the International Tax Competitiveness Index to compare the ways that countries structure their tax systems.

The International Tax Competitiveness Index

The International Tax Competitiveness Index (ITCI) seeks to measure the extent to which a country’s tax system adheres to two important aspects of tax policy: competitiveness and neutrality.

A competitive tax code is one that keeps marginal tax rates low. In today’s globalized world, capital is highly mobile. Businesses can choose to invest in any number of countries throughout the world to find the highest rate of return. This means that businesses will look for countries with lower tax rates on investment to maximize their after-tax rate of return. If a country’s tax rate is too high, it will drive investment elsewhere, leading to slower economic growth. In addition, high marginal tax rates can lead to tax avoidance.

According to research from the OECD, corporate taxes are most harmful for economic growth, with personal income taxes and consumption taxes being less harmful. Taxes on immovable property have the smallest impact on growth.[3]

Separately, a neutral tax code is simply one that seeks to raise the most revenue with the fewest economic distortions. This means that it doesn’t favor consumption over saving, as happens with investment taxes and wealth taxes. This also means few or no targeted tax breaks for specific activities carried out by businesses or individuals.

A tax code that is competitive and neutral promotes sustainable economic growth and investment while raising sufficient revenue for government priorities.

There are many factors unrelated to taxes which affect a country’s economic performance. Nevertheless, taxes play an important role in the health of a country’s economy.

To measure whether a country’s tax system is neutral and competitive, the ITCI looks at more than 40 tax policy variables. These variables measure not only the level of taxes, but also how taxes are structured. The Index looks at a country’s corporate taxes, individual income taxes, consumption taxes, property taxes, and the treatment of profits earned overseas. The ITCI gives a comprehensive overview of how developed countries’ tax codes compare, explains why certain tax codes stand out as good or bad models for reform, and provides important insight into how to think about tax policy.

Due to some data limitations, recent tax changes in some countries may not be reflected in this year’s version of the International Tax Competitiveness Index.

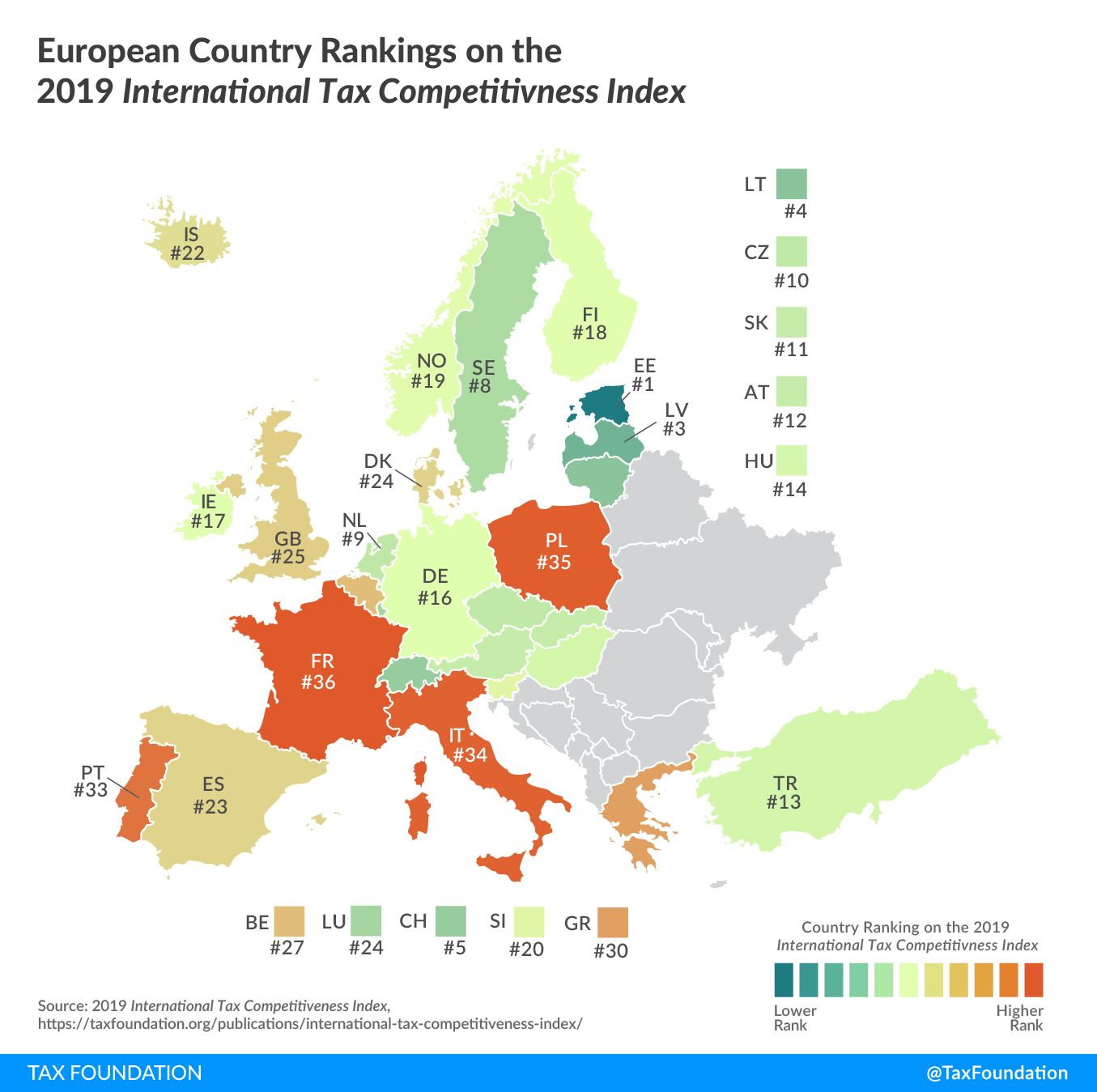

2019 Rankings

For the sixth year in a row, Estonia has the best tax code in the OECD. Its top score is driven by four positive features of its tax code. First, it has a 20 percent tax rate on corporate income that is only applied to distributed profits. Second, it has a flat 20 percent tax on individual income that does not apply to personal dividend income. Third, its property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services. applies only to the value of land, rather than to the value of real property or capital. Finally, it has a territorial tax system that exempts 100 percent of foreign profits earned by domestic corporations from domestic taxation, with few restrictions.

Table 1

| Country | Overall Rank | Overall Score | Corporate Tax Rank | Individual Taxes Rank | Consumption Taxes Rank | Property Taxes Rank | International Tax Rules Rank | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estonia | 1 | 100 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 11 | |

| New Zealand | 2 | 86.3 | 24 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 9 | |

| Latvia | 3 | 86 | 1 | 6 | 29 | 6 | 7 | |

| Lithuania | 4 | 81.5 | 3 | 3 | 24 | 7 | 17 | |

| Switzerland | 5 | 79.3 | 8 | 10 | 1 | 34 | 1 | |

| Luxembourg | 6 | 77 | 23 | 16 | 4 | 19 | 5 | |

| Australia | 7 | 76.4 | 28 | 15 | 8 | 3 | 12 | |

| Sweden | 8 | 75.5 | 6 | 19 | 16 | 5 | 14 | |

| Netherlands | 9 | 72.5 | 19 | 21 | 12 | 12 | 3 | |

| Czech Republic | 10 | 72.2 | 9 | 5 | 34 | 13 | 6 | |

| Slovak Republic | 11 | 71.4 | 14 | 2 | 33 | 4 | 31 | |

| Austria | 12 | 71.4 | 17 | 29 | 11 | 10 | 4 | |

| Turkey | 13 | 69 | 18 | 7 | 20 | 18 | 16 | |

| Hungary | 14 | 68.6 | 4 | 8 | 35 | 25 | 2 | |

| Canada | 15 | 67 | 20 | 25 | 7 | 20 | 18 | |

| Germany | 16 | 66.9 | 26 | 26 | 10 | 16 | 8 | |

| Ireland | 17 | 66.9 | 5 | 33 | 23 | 11 | 13 | |

| Finland | 18 | 66.8 | 7 | 27 | 15 | 14 | 23 | |

| Norway | 19 | 66.2 | 12 | 13 | 18 | 24 | 20 | |

| Slovenia | 20 | 65.1 | 10 | 17 | 30 | 22 | 15 | |

| United States | 21 | 63.7 | 21 | 24 | 5 | 29 | 28 | |

| Iceland | 22 | 61.8 | 11 | 28 | 19 | 23 | 22 | |

| Spain | 23 | 60.3 | 22 | 14 | 14 | 32 | 19 | |

| Denmark | 24 | 60.1 | 16 | 34 | 17 | 8 | 29 | |

| United Kingdom | 25 | 60.1 | 15 | 22 | 22 | 31 | 10 | |

| Korea | 26 | 59.5 | 33 | 20 | 2 | 26 | 34 | |

| Belgium | 27 | 57.2 | 25 | 11 | 26 | 27 | 25 | |

| Japan | 28 | 57.1 | 36 | 32 | 3 | 30 | 21 | |

| Mexico | 29 | 54.2 | 32 | 12 | 25 | 9 | 35 | |

| Greece | 30 | 52.9 | 29 | 18 | 31 | 28 | 26 | |

| Israel | 31 | 51.9 | 27 | 36 | 13 | 15 | 33 | |

| Chile | 32 | 49.1 | 30 | 23 | 28 | 17 | 36 | |

| Portugal | 33 | 46.6 | 34 | 30 | 32 | 21 | 30 | |

| Italy | 34 | 44 | 31 | 31 | 27 | 35 | 27 | |

| Poland | 35 | 43.5 | 13 | 9 | 36 | 33 | 32 | |

| France | 36 | 42.7 | 35 | 35 | 21 | 36 | 24 | |

While Estonia’s tax system is the most competitive in the OECD, the other top countries’ tax systems receive high scores due to excellence in one or more of the major tax categories. New Zealand has a relatively flat, low-rate individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. that also exempts capital gains (with a combined top rate of 33 percent), a well-structured property tax, and a broad-based value-added tax. Latvia, which recently adopted the Estonian system for corporate taxation, also has a relatively efficient system for taxing labor. Lithuania has the third lowest corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate at 15 percent, a relatively neutral treatment of capital investment costs, and a well-structured individual income tax system. Switzerland has a relatively low corporate tax rate (21.1 percent), a low, broad-based consumption tax, and a relatively flat individual income tax that exempts capital gains from taxation. Sweden has a lower-than-average corporate income tax rate of 21.4 percent, no estate or wealth taxes, and a well-structured value-added tax and individual income tax.

For the sixth year in a row, France has the least competitive tax system in the OECD. It has one of the highest corporate income tax rates in the OECD (34.4 percent), high property taxes, a net tax on real estate wealth, a financial transaction tax, and an estate tax. France also has high, progressive, individual income taxes that apply to both dividend and capital gains income.

In general, countries that rank poorly on the ITCI levy relatively high marginal tax rates on corporate income. The five countries at the bottom of the rankings all have higher than average corporate tax rates, except for Poland, at 19 percent. In addition, all five countries have high consumption taxes, with rates of 20 percent or higher, except for Chile, at 19 percent.

Notable Changes from Last Year[4]

Belgium

Belgium’s ranking fell from 22nd to 27th after adopting a set of international tax rules following an EU directive. Belgium now has both Controlled Foreign Corporation rules and thin capitalization rules that hurt its ranking on international tax regulations.

Canada

Canada adjusted its corporate income tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. by providing expanding write-offs for capital investments in machinery and buildings. It followed the United States by providing for full expensing for short-lived assets. Canada improved from 20th to 15th.

Ireland

Ireland’s ranking fell from 14th to 17th after adopting a new Controlled Foreign Corporations regime. These rules apply tax to passive income earned by or attributed to a foreign subsidiary simply for tax purposes (non-genuine arrangements). This reduced its score for international tax regulations.

Korea

In 2019, Korea continued to reduce the ability for businesses to offset future tax liability with current losses. Losses are currently allowed to be carried forward for 10 years, but they are capped at 60 percent of taxable income for large companies. Korea’s rank fell from 24th to 26th.

Poland

Poland adopted a patent box that provides a reduced corporate rate of 5 percent on qualified intellectual property income. Poland’s rank fell from 32nd to 35th.

Slovenia

As is the case in several other EU countries, Slovenia adopted new Controlled Foreign Corporation legislation. The new rules apply to passive income. Slovenia’s rank fell from 17th to 20th.

Turkey

Turkey’s rank improved from 16th to 13th. Three measures of compliance time with corporate income, individual income, and consumption taxes have shown significant improvement in the last several years. Average corporate tax compliance time fell to 24 hours from 44.5 in 2018; individual income tax compliance time fell to 71 hours from 91 hours in 2018; and consumption taxA consumption tax is typically levied on the purchase of goods or services and is paid directly or indirectly by the consumer in the form of retail sales taxes, excise taxes, tariffs, value-added taxes (VAT), or income taxes where all savings are tax-deductible. compliance time fell to 75 hours from 80 hours.

Table 2

| Country | 2017 Rank | 2017 Score | 2018 Rank | 2018 Score | 2019 Rank | 2019 Score | Change in Rank from 2018 to 2019 | Change in Score from 2018 to 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 9 | 75 | 9 | 72.3 | 7 | 76.4 | 2 | 4.1 | |

| Austria | 10 | 71.5 | 11 | 69.2 | 12 | 71.4 | -1 | 2.1 | |

| Belgium | 22 | 64.8 | 22 | 60.2 | 27 | 57.2 | -5 | -3 | |

| Canada | 20 | 65.4 | 20 | 62.5 | 15 | 67 | 5 | 4.6 | |

| Chile | 33 | 49.3 | 33 | 46.7 | 32 | 49.1 | 1 | 2.4 | |

| Czech Republic | 12 | 71.3 | 12 | 68.4 | 10 | 72.2 | 2 | 3.8 | |

| Denmark | 23 | 63.9 | 23 | 60.2 | 24 | 60.1 | -1 | 0 | |

| Estonia | 1 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 0 | |

| Finland | 14 | 67 | 15 | 64.9 | 18 | 66.8 | -3 | 2 | |

| France | 36 | 39.1 | 36 | 40.4 | 36 | 42.7 | 0 | 2.3 | |

| Germany | 15 | 66.8 | 18 | 63.7 | 16 | 66.9 | 2 | 3.2 | |

| Greece | 31 | 53.1 | 31 | 49.5 | 30 | 52.9 | 1 | 3.4 | |

| Hungary | 17 | 66.1 | 13 | 66.4 | 14 | 68.6 | -1 | 2.2 | |

| Iceland | 24 | 62.6 | 25 | 59.7 | 22 | 61.8 | 3 | 2.1 | |

| Ireland | 16 | 66.2 | 14 | 64.9 | 17 | 66.9 | -3 | 2 | |

| Israel | 30 | 53.4 | 30 | 49.6 | 31 | 51.9 | -1 | 2.4 | |

| Italy | 35 | 46.9 | 35 | 43.3 | 34 | 44 | 1 | 0.7 | |

| Japan | 26 | 60.4 | 28 | 55.2 | 28 | 57.1 | 0 | 1.8 | |

| Korea | 18 | 66.1 | 24 | 59.9 | 26 | 59.5 | -2 | -0.4 | |

| Latvia | 2 | 84.1 | 2 | 83.8 | 3 | 86 | -1 | 2.3 | |

| Lithuania | 5 | 78.8 | 4 | 78.7 | 4 | 81.5 | 0 | 2.8 | |

| Luxembourg | 4 | 79 | 5 | 76.6 | 6 | 77 | -1 | 0.4 | |

| Mexico | 29 | 55.2 | 29 | 52.2 | 29 | 54.2 | 0 | 1.9 | |

| Netherlands | 6 | 77.2 | 7 | 74.9 | 9 | 72.5 | -2 | -2.4 | |

| New Zealand | 3 | 82.7 | 3 | 81.6 | 2 | 86.3 | 1 | 4.6 | |

| Norway | 21 | 65 | 19 | 63.4 | 19 | 66.2 | 0 | 2.8 | |

| Poland | 32 | 51.2 | 32 | 48.3 | 35 | 43.5 | -3 | -4.8 | |

| Portugal | 34 | 48.7 | 34 | 44.7 | 33 | 46.6 | 1 | 1.9 | |

| Slovak Republic | 11 | 71.5 | 10 | 70.7 | 11 | 71.4 | -1 | 0.7 | |

| Slovenia | 19 | 65.5 | 17 | 63.9 | 20 | 65.1 | -3 | 1.2 | |

| Spain | 25 | 60.4 | 27 | 57.3 | 23 | 60.3 | 4 | 3 | |

| Sweden | 8 | 76.5 | 8 | 73.1 | 8 | 75.5 | 0 | 2.4 | |

| Switzerland | 7 | 76.9 | 6 | 75.3 | 5 | 79.3 | 1 | 4 | |

| Turkey | 13 | 67.6 | 16 | 64.7 | 13 | 69 | 3 | 4.3 | |

| United Kingdom | 27 | 60 | 26 | 57.7 | 25 | 60.1 | 1 | 2.4 | |

| United States | 28 | 57.8 | 21 | 60.9 | 21 | 63.7 | 0 | 2.8 |

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom reversed a policy that eliminated capital expenditure deductions for the costs of investing in buildings. The new policy provides businesses with a 2 percent annual allowance for spending on industrial buildings. This effectively provides businesses with the ability to recover 27.9 percent of their building costs in present value. The UK’s rank improved from 26th to 25th.

Explore Our New Interactive Tool

Notes

[1] Elke Asen and Daniel Bunn, “Sources of Government Revenue in the OECD, 2019,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 23, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/publications/sources-of-government-revenue-in-the-oecd/.

[2] Daniel Bunn, “Ripple Effects from Controlled Foreign Corporation Rules,” Tax Foundation, June 13, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/controlled-foreign-corporation-rules-effects/.

[3] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “Tax and Economic Growth,” Economics Department Working Paper No. 620, July 11, 2008.

[4] Last year’s scores published in this report can differ from previously published rankings due to both methodological changes and corrections made to previous years’ data.

Share this article