Key Findings

- The TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) reformed the U.S. system for taxing international corporate income. Understanding the impact of TCJA’s international provisions thus far can help lawmakers consider how to approach international tax policy in the coming years.

- International tax policy must balance competing objectives, such as maximizing revenue and growth while minimizing profit shiftingProfit shifting is when multinational companies reduce their tax burden by moving the location of their profits from high-tax countries to low-tax jurisdictions and tax havens. and complexity.

- The TCJA’s international changes—a transition to a territorial system with worldwide elements, and some anti-base-erosion measures—were an attempt to balance those competing objectives.

- The TCJA’s international system’s “global minimum tax,” known as GILTI, raises substantial revenue, but it may lose much of its revenue as countries work to comply with Pillar Two.

- The TCJA’s incentive to keep highly mobile profits in the U.S., known as FDII, has been somewhat successful in curbing profit shifting.

- A rule known as BEAT, which disallows the overuse of cross-border tax deductions commonly associated with profit shifting as measured by accounting data, may not be as effective as projected.

- Reformers should build on what these provisions got right and modify them where they fail or where they become incompatible with international tax developments.

Introduction

In 2017, Congress passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, a broad tax law that included significant changes to the U.S. international corporate tax system. The TCJA reduced the headline corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, while reforming the taxation of income earned abroad by U.S. multinational enterprises (MNEs).

The pre-2017 system could be called a worldwide system with deferral. That is, U.S. MNEs nominally owed the full U.S. corporate income tax rate on profits earned abroad, but only when the profits were “repatriated.” The post-2017 system could be called a territorial system with base erosion measures. The U.S. no longer lays claim to all worldwide corporate income, but it has rules intended to prevent firms from avoiding U.S. tax by attributing their income to low-tax jurisdictions (i.e., profit shifting). The TCJA international system improved upon its predecessor, but it, too, has flaws and will likely need revision before the end of 2026.

Tax policy around the world has changed since 2017 and will continue to change in the next few years. A global tax agreement known as Pillar Two, brokered by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), begins to go into effect this year and intends to establish a global minimum rate of 15 percent. TCJA’s international provisions resemble some Pillar Two rules, but TCJA and Pillar Two clash on some specific details. Pillar Two includes a safe harbor provision that will effectively insulate the U.S. from major problems through December 31, 2026. However, beyond that date, a mismatch between U.S. rules and Pillar Two rules may be costly in terms of compliance efforts and tax liabilities.

The 119th Congress will likely be interested in addressing Pillar Two in 2025 or 2026, perhaps in legislation that also addresses the scheduled expiration of many of TCJA’s individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. provisions. In doing so, it is likely to revamp some of TCJA’s international provisions—the base erosion measures mentioned above.

Below is a review of three major international provisions of the TCJA, known as global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI), foreign-derived intangible income (FDII), and base erosion and anti-abuse tax (BEAT). A strong understanding of their rationale, impact, and most likely interactions with Pillar Two will be helpful in designing future modifications to the system.

Defining Objectives in International Tax Policy

To evaluate TCJA’s international policies against its predecessors or successors, one must consider the objectives of international corporate tax policy. What goals might policymakers hope to accomplish? There are several to keep in mind, and they often conflict with each other, forcing us to consider trade-offs between them.

Raise Revenue

The principal goal of tax policy is to raise revenue. Every tax has flaws, and those flaws tend to become unwieldy at higher rates. But the best one can do is select the taxes with the most manageable flaws for a given revenue target.

U.S. international provisions could generate revenues in two ways. First, they could tax income genuinely earned abroad by U.S. firms. Second, and more importantly, they can protect the domestic tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. —that is, prevent MNEs from avoiding U.S. taxes by profit shifting.

The second goal is more important, at least for the U.S., because the U.S. domestic market is so large, and because U.S. firms are disproportionately concentrated in it, even after accounting for its size.

Make the U.S. an Attractive Place for Investment

Tax policy should also make the U.S. an attractive destination for investment, both by U.S. firms and by foreign ones. Capital investments—including physical capital like buildings or equipment, and even more abstract forms of investment like organizational know-how—are complementary to workers’ efforts and skills, raising their productivity. At the national level, greater capital investment makes for higher gross domestic product (GDP) and higher living standards.

Make U.S. Firms Globally Competitive

It is also in the U.S.’s interest to facilitate the success of U.S. firms abroad. If a U.S. firm and a foreign firm are competing to succeed in a third market, Americans should generally prefer that the U.S. firm win a greater market share. This may include investing abroad, hiring abroad, and earning revenues and profits abroad. On average, these activities are beneficial for U.S. citizens, even though they happen elsewhere.

One simple reason this might be the case is that Americans are disproportionately likely to be shareholders of American MNEs, and they earn greater dividends or capital gains on their holdings. More subtly, some jobs located in U.S. corporate headquarters are effectively global in function. Success abroad may mean more and better jobs in the MNE’s home city. Even Americans who don’t hold one of those jobs benefit from having deeper-pocketed customers around them. Finally, the U.S. benefits from business activity flowing through the U.S. financial system, rather than European or Asian currencies and stock exchanges. Such activity is more likely to increase demand for the U.S. dollar, entrenching it as the global reserve currency, and more likely to increase demand for U.S. financial services of all kinds. All in all, foreign success by U.S. firms is complementary to success at home.

In a few cases, politics may focus on examples where foreign activity seems to be a substitute for domestic activity instead—for example, two countries may compete over the manufacturing of a tradable good for use in both markets. But these cases are more the exception than the rule. In sectors like retail, transportation services, resource extraction, hospitality, or health care, investment in one place doesn’t come at the expense of another place. Empirical research tends to show that foreign investment is associated with greater domestic investment, lending more credibility to the notion that these are complementary.[1]

As many countries desire to let their MNEs compete globally without disadvantages, they often assess comparatively little or no tax on foreign earnings, a design known as a “territorial” system. However, territorial systems are vulnerable to profit shifting and generally require measures to defend their tax bases.[2]

Reduce Compliance Costs

Finally, an international tax code should avoid being overly complex or cluttered. People may dislike complexity for a variety of reasons, but the most important is that international tax compliance occupies the time and efforts of intelligent, productive people who would be quite valuable elsewhere. As international tax compliance absorbs those people, the rest of the economy loses out on their efforts.

Naturally, these goals conflict with each other. Business competitiveness goals are at odds with revenue-raising goals. Preventing profit shifting requires rules about which profits belong where, which is extremely complex when profits are earned through “intangible” assets or over the internet, without a clear physical location. The job of international tax policymakers is to muddle through as best they can, recognizing they will have to compromise on all of these objectives.

Defining the Flaws of the Pre-2017 System

In 2017, the TCJA’s architects hoped to address the U.S. corporate tax system’s considerable flaws. The U.S. had a corporate income tax rate of 35 percent, which applied to both domestic income and repatriated income earned abroad. However, the tax on income abroad would subtract a credit for any foreign income taxes paid, and, even more importantly, MNEs could defer repatriationTax repatriation is the process by which multinational companies bring overseas earnings back to the home country. Prior to the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the U.S. tax code created major disincentives for U.S. companies to repatriate their earnings. Changes from the TCJA eliminate these disincentives. for years or even decades.

This system was out of step with the rest of the world’s practices, and it was functioning poorly. The U.S. rate was the highest corporate tax rate among all OECD countries in 2017 and among the highest in the world.[3] Furthermore, all but six OECD countries had abandoned worldwide systems in favor of territorial systems by 2017.[4] Today, that number has declined to four.[5]

This system created two major distortions. The first distortion was that it encouraged corporations to delay repatriation as long as possible. The farther into the future the tax is assessed, the better.

The incentives governing corporate income held abroad were similar to those of a retirement saver holding money in a traditional individual retirement account (IRA): no tax owed until withdrawal. IRAs are often referred to as “tax-advantaged” relative to ordinary brokerage or saving accounts because they allow compounding before tax is due. By contrast, an account subject to annual income tax would have to forgo some compound returns on the tax money.

In the same way that retirement savers try to maximize their use of IRAs, corporations before 2017 attempted to maximize earnings reported and held abroad.

While the worldwide deferral system didn’t make much revenue or much sense, it did not necessarily keep investment capital out of the U.S.; highly profitable global firms could find alternative routes to raising domestic capital when they needed to.

The second distortion created by the pre-TCJA international system was companies effectively renouncing their U.S. citizenship. Among those companies that could not shield themselves from U.S. worldwide taxation, the system encouraged them to “invert”—that is, move their legal headquarters outside of the U.S. so that they would no longer be subject to U.S. taxes on non-U.S. income.

In addition to these two distortions, the pre-2017 U.S. tax system was vulnerable to profit shifting, a problem from which no corporate tax system is fully immune. Even though U.S. MNEs nominally owed a 35 percent tax rate on any profits, domestic or international, they were best served by attributing profits to international jurisdictions with low tax rates, to pay a small burden when the profits were earned and delay the rest of the 35 percent until much later.

Although many profits could be deferred or shifted, there were some limitations to these practices. Under a provision called Subpart F, passive income such as interest, dividends, rents, and royalties were taxed worldwide without deferral. This would prevent some of the most obvious schemes for locating subsidiaries with valuable intangible assets in low-tax countries in order to make deductible payments that count against U.S. taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. , “stripping” U.S. earnings to low-tax countries. However, many MNEs were capable of more sophisticated schemes that would avoid Subpart F and nonetheless reduce U.S. taxable income.

TCJA’s Approach

TCJA addressed these issues by reducing the corporate income tax rate and moving toward a territorial system—effectively relinquishing many U.S. claims on foreign income of U.S. MNEs—while adding more base erosion measures to curb profit shifting.

The first item—the lower 21 percent domestic corporate income tax rate—is relevant to international tax policy in that it is easier to “defend” from profit shifting. The lower the domestic rate, the less incentive firms have to reclassify domestic profits. Unfortunately, the lower rate came at a substantial cost to revenues, requiring other revenue-raising provisions to “pay for” it. In some cases, this came out to a beneficial trade—for example, lower rates on corporate income coupled with reduced deductibility of interest ameliorated the tax code’s debt-equity bias.[6] However, other revenue-raising provisions, like research and development amortization, were less worthwhile.[7]

Next, TCJA included a participation exemption, meaning that foreign profits of U.S. companies would be exempt from U.S. tax under certain conditions involving holding periods, ownership stakes, and taxes paid to foreign jurisdictions. A participation exemption is the core of a territorial system, and it was the international norm by the time TCJA was enacted.

The participation exemption put U.S. MNEs on an equal footing when doing business abroad, as they no longer had to pay an extra layer of tax. For example, if a British MNE and an American MNE under the U.S. worldwide system competed against each other in Germany, the British firm would only pay taxes to Germany, while the American firm would anticipate additional U.S. taxes. After TCJA, the U.S. firm would pay only German taxes on its German operations, just like its British counterpart.

A drawback of participation exemptions, however, is that they can make a system more vulnerable to profit shifting. To defend against profit shifting, TCJA included base erosion measures. These are typical of countries with territorial systems. And they often partially walk back the territoriality of the tax system, effectively including elements of a worldwide system—after all, they concern themselves with income a firm would like to label as foreign.[8] However, though TCJA incorporates some elements of a worldwide system, it does not have much in common with the particular U.S. system that it replaced. TCJA’s worldwide system is built around low tax rates without deferral—effectively, the opposite of the high rate and generous deferral system the U.S. had prior to 2017.

The three most significant base erosion provisions are GILTI, FDII, and BEAT. GILTI is a category of foreign income added back into taxable income for U.S. corporations, but it is partially deductible, reducing the effective rate paid on that income, and it contains a partial foreign tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. . FDII is a counterpart to GILTI, a term for intangible and global income that the MNE attributes to the U.S. FDII is also taxed at a low rate, effectively rewarding companies for choosing the U.S. as the location for their highly mobile income. Finally, BEAT is a special minimum tax that applies to firms with too many “base erosion” payments—that is, expenses paid to related corporations abroad in categories often associated with profit shifting. The minimum tax disallows deductions for base erosion payments, effectively nullifying excessive earnings stripping.

Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income

The tax on GILTI is somewhat complex, and Tax Foundation has provided more detailed example calculations elsewhere.[9] But most of its crucial dynamics can be understood through four main elements of the calculation.

The first element of the calculation is the sum of income of foreign affiliates, known as net tested income. Notably, the GILTI calculation is “blended,” meaning it sums all countries together; it is not, under current law, a country-by-country calculation.

Second, the MNE may subtract what is called the qualified business asset investment (QBAI) exemption. The QBAI exemption is an imputed 10 percent return on depreciable foreign assets. Effectively, businesses earning returns from large, substantive investments abroad can expect a large reduction in their GILTI tax base, placing more of the burden of GILTI on businesses earning high margins with intangible assets and markups. After subtracting QBAI, the MNE has its GILTI tax base.

Third, the MNE deducts 50 percent of its GILTI. This effectively means that GILTI is taxed at only half of the normal corporate income tax rate (10.5 percent instead of 21 percent). This deduction is scheduled to fall to 37.5 percent at the end of 2025, meaning that GILTI will be taxed at 5/8 of the normal corporate income tax rate.

Fourth, the MNE is credited for foreign taxes paid, but only at 80 percent of the value, and not to exceed total GILTI liability.

Knowing these design elements can help an observer understand both GILTI’s intent and effects.

Aimed at Supernormal Returns and Profit Shifting, not Normal Activity

The QBAI exemption in GILTI may appear arbitrary, and its rationale may not be obvious at first glance. But it is arguably an attempt at approximating something important: a distinction between two types of corporate income. Some corporate income is characterized more by modest returns on tangible investments. And some corporate income is characterized by high-margin returns on intangible investments. By exempting a 10 percent return on some assets, QBAI shifts the burden of GILTI towards returns that are inframarginal and indicative of highly mobile markups derived from valuable intangibles.

There are two points to be made here. First, and most importantly in the realm of international taxes, high margins often indicate that a firm is profiting from some abstract, non-physical factor of production, like an idea, that gives it a competitive advantage. And of course, a U.S.-headquartered MNE’s best ideas and intangible assets are likely to be most attributable to U.S. efforts.

A combination of high margins and low foreign tax rates, then, is circumstantial evidence that a firm has benefited from intangibles primarily developed in the U.S. but has then taken advantage of intangibles’ non-physical nature to allocate returns to low-tax jurisdictions.

GILTI, despite its homonym, is not a definitive indicator of guilt. However, its drafters understood that a certain tax profile is often consistent with profit shifting and chose to allocate tax burdens more heavily towards MNEs with that profile.

In addition to this main rationale, a more general principle of tax policy, not exclusive to the international realm, justifies the QBAI exemption: ideally, taxes should fall on investments so valuable that they would have been made anyway. A heavy tax burden on a generic capital investment with a modest return—a marginal investment—might disincentivize people from investing in that asset in the first place. By contrast, a tax burden on a wildly profitable capital investment’s returns, an inframarginal investment, would not dissuade the firm from making that investment. The structure of QBAI helps the GILTI system tax inframarginal investments more, and marginal investments less.

Less than Half Worldwide

While GILTI is, in many respects, a worldwide tax systemA worldwide tax system for corporations, as opposed to a territorial tax system, includes foreign-earned income in the domestic tax base. As part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the United States shifted from worldwide taxation towards territorial taxation. , the formula’s elements demonstrate why the U.S. is significantly closer to territorial than worldwide as a whole. Only half of GILTI counts towards the corporate income tax, or 5/8 even after the formula tightens at the end of 2025. Furthermore, GILTI enjoys both the QBAI exemption and a foreign tax credit. The result is a system that is considerably less than half the U.S. domestic rate.

This is roughly consistent with other countries that have territorial systems. Many of them have a participation exemption, excusing most foreign income from tax, but also some form of controlled foreign corporation (CFC) rules, bringing back in certain classes of foreign income most likely to be shifted profits.

All in all, GILTI is tougher on taxpayers than a typical CFC regime, or the proposed Pillar Two income inclusion rule (IIR). On a variety of technical details, like substance carveouts, expense allocation, and carryforwards, GILTI is less generous than some of its counterparts. In fact, Tax Foundation modeling shows that GILTI raises more revenue than a Pillar Two IIR would raise.[10]

Goldilocks Principle of Foreign Taxes

The foreign tax credit design fully incentivizes MNEs to shop for lower taxes, up to a point. If a firm gets its global tax rate down from 20 percent to 19 percent, it keeps the money. GILTI liability is fully zeroed out already through foreign tax credits. Any additional foreign tax credits going from 19 percent to 20 percent are effectively wasted. However, once they get into the range in which they have GILTI liability—for example, an 8 percent rate—the U.S. claws back most of the money from additional tax avoidance.

The result is a kind of Goldilocks principle. If a firm reduces its tax burden among foreign governments by a little bit, the U.S. lets it keep its rewards. If a firm reduces its tax burden on foreign income by a lot, that is suspicious, and perhaps indicative of profit shifting.

Notably, this Goldilocks mean where it lumps all other countries into a “rest of world” category shows it is primarily about U.S. interests vis-à-vis the rest of the world, with little or no concern for dynamics among the rest of the world’s countries. The GILTI calculation effectively asks whether an MNE with income abroad is paying low tax rates in general, not whether it is paying low rates in specific countries. A moderate amount of income in low tax countries is not punished, and indeed, it can be rewarded under certain circumstances. Some income in a low-tax country can offset income in high-tax countries and achieve a moderate rate overall, allowing the firm to use foreign tax credits that would otherwise be wasted.

GILTI’s formula, then, is not fully oriented toward a project of eliminating low-tax countries. Instead, it merely disincentivizes the overuse of low-tax jurisdictions by U.S. MNEs.

This contrasts with Pillar Two, which is indeed a project designed to combat low-tax countries more directly. Pillar Two’s equivalent of GILTI, the IIR, uses country-by-country calculations, penalizing low taxes at the country level even when a blended system like GILTI would show high taxes paid elsewhere.

Double TaxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. Problems in GILTI Design

Though GILTI was intended to increase the tax burden only on foreign income taxed at low rates, some quirks of its expense allocation rules resulted in double taxation of even high-taxed income, contrary to GILTI’s name and stated goals. As stated above, the expense allocation rules are one reason GILTI may be less taxpayer-friendly than an IIR; GILTI can in some cases act as a surtaxA surtax is an additional tax levied on top of an already existing business or individual tax and can have a flat or progressive rate structure. Surtaxes are typically enacted to fund a specific program or initiative, whereas revenue from broader-based taxes, like the individual income tax, typically cover a multitude of programs and services. on income that was already taxed relatively highly.[11] In 2020, the IRS released guidance to partially fix the problem through regulatory observation.[12] However, the expense allocation in GILTI deserves a more comprehensive fix from Congress.[13]

The Revenue Workhorse of TCJA’s International Reforms

GILTI is the most significant persistent revenue-raising element of TCJA. (A one-time transition tax, which closed out the outstanding deferred earnings abroad from the previous tax system by taxing them at a low rate, also raised significant revenue, but will not continue to raise revenue in the future.)

TCJA’s international reforms were roughly revenue neutral, allowing the corporate income tax components of the law to be made permanent, even under budget reconciliation rules. However, the initial Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) projections likely underestimated GILTI revenues and overestimated BEAT revenues. The committee’s initial 10-year estimates at the time TCJA was passed held that BEAT would raise $149.6 billion to GILTI’s $112.4 billion.[14]

By 2021, however, real corporate income tax return data showed a much different story. JCT collected a sample of 81 large C corporations in 2018 and showed that those corporations paid $6.3 billion of GILTI tax liability after foreign tax credits, but just $0.07 billion of BEAT liability.[15] (This quantification of BEAT would not include higher ordinary corporate tax payments induced by MNEs strategizing to avoid BEAT.)

Precise estimates for GILTI revenue are difficult, as corporate income tax revenue is generally volatile, and especially so when it interacts with foreign jurisdictions that may change their own laws or multinational corporations that may change their behavior. However, Tax Foundation has estimated that GILTI will raise $19.1 billion in 2024 and $37.0 billion in 2028.[16] A comparable estimate from Tax Policy Center shows $14.8 billion in 2024 and $26.3 billion in 2028.[17] These numbers are small relative to the corporate income tax as a whole, and even smaller relative to the individual income tax as a whole—but international corporate revenues have always been small. Many corporate profits are fully domestic, and for those that are international, the U.S. gets the second bite at the apple, not the first.

The fast rise in projected revenues from GILTI is largely a consequence of the scheduled decrease in the GILTI deduction to 37.5 percent.

Measuring Tax Parity Correctly

The differential between U.S. domestic rates and GILTI rates may lead an observer to compare them directly and conclude that activity overseas receives better tax treatment. However, it is important to note that GILTI is a secondary top-up rate that might be assessed in addition to a jurisdiction’s domestic tax. It is aimed at boosting tax rates where on-paper profit shifting seems likely. It is not reducing the tax rates on real investments in large markets that have their own corporate tax rates.

Similarly, one notable critique of QBAI has been that it incentivizes overseas investments, perhaps at the expense of domestic investments. It certainly protects investments abroad from an additional layer of tax, incentivizing them to some degree. But investments abroad are often complements, not substitutes, to domestic investments.[18] And more importantly, the main purpose of QBAI is to be a backward-looking “substance test” for profits located overseas, not a prospective incentive.

Foreign-Derived Intangible Income

Foreign-derived intangible income is a new category of income defined as a kind of U.S.-based counterpart to GILTI. Much like GILTI, it is structured around an excess return over QBAI and partially (37.5 percent) excluded from taxable income to get a much lower rate than the headline corporate income tax rate. In general, over the long run, FDII and GILTI rates will be roughly equal for companies choosing where to locate intangible assets.

The purpose of FDII, then, is to incentivize MNEs to locate their intellectual property in the U.S. by offering a discount to income that would otherwise be particularly easy and remunerative to shift abroad. Income associated with intangibles is easy to shift, and that is particularly true when the customers are already located outside of the U.S., so FDII, recognizing the high tax elasticity of this kind of income, offers a competitive rate.

FDII is in this respect a competitor to so-called “patent boxA patent box—also referred to as intellectual property (IP) regime—taxes business income earned from IP at a rate below the statutory corporate income tax rate, aiming to encourage local research and development. Many patent boxes around the world have undergone substantial reforms due to profit shifting concerns. ” regimes in Europe, many of which also offer low rates for varieties of income thought to be highly mobile.[19]

FDII as an Attractor of Inbound Profit Shifting

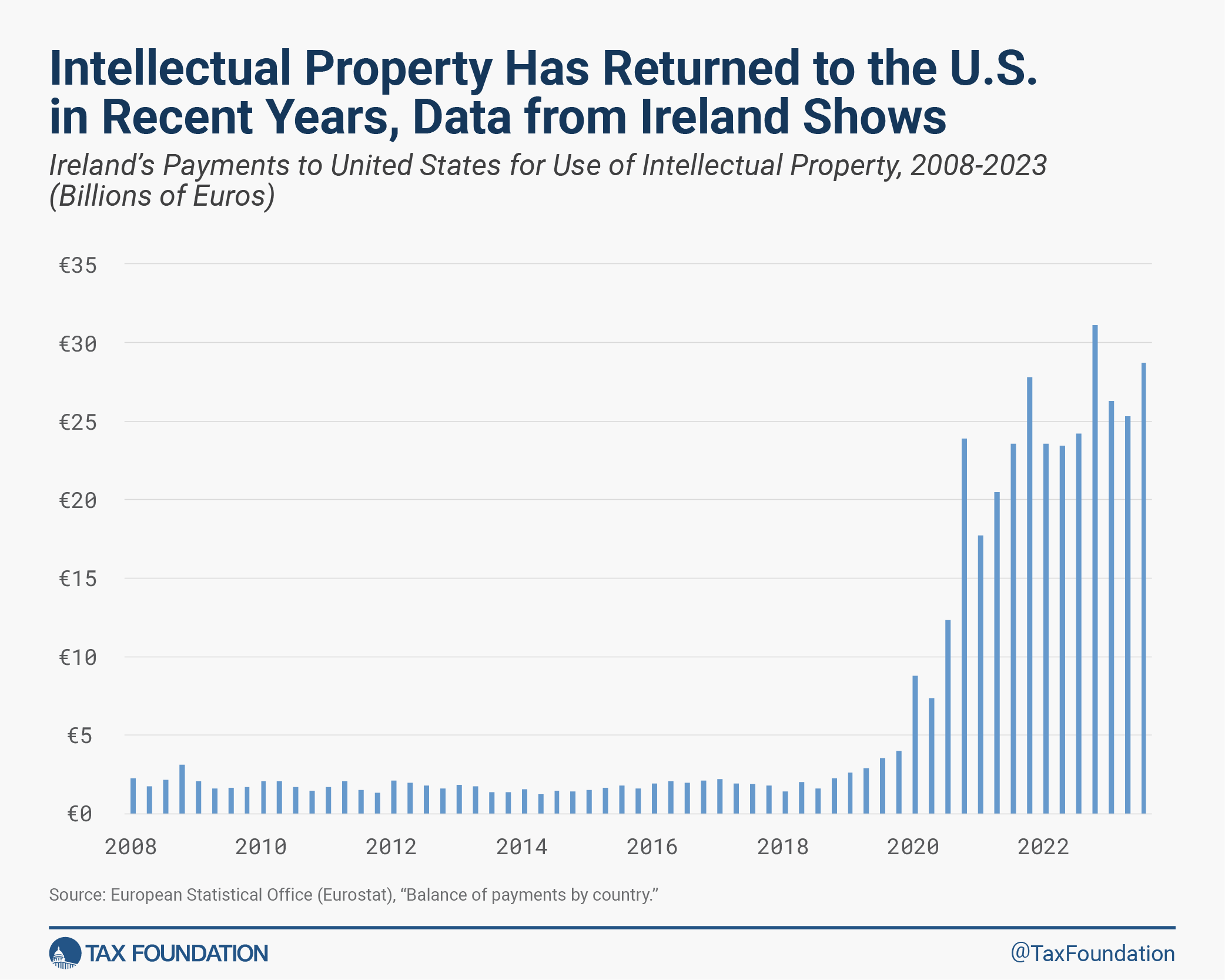

Irish balance of payments data shows that FDII has been somewhat effective in its intended role, driving intellectual property back toward the United States. As Ireland is a global hub for reported corporate income, its import and export data frequently reveal truths about corporate tax planning, rather than the specific trading proclivities of Irish citizens.

In a trend first noted by Irish economist Seamus Coffey in 2021, Irish payments to the United States for intellectual property hovered around €2 billion per quarter for most of the economic expansion of the 2010s. However, TCJA took effect at the beginning of 2018, and by the last quarter of 2019, the payments rose past €4 billion for the first time. By the last quarter of 2020, they skyrocketed to nearly €24 billion.

Coffey further shows that the overall amount of Irish payments for intellectual property did not change much. Instead, merely the destination changed. Payments that previously went to other parts of the Eurozone or offshore financial centers had changed destinations to the United States.

An extended data series showing the continued trajectory of this indicator can be found in Figure 1:

Coffey attributed the trend, which has only continued to greater heights, to a combination of the OECD’s project on income shifting, changes to Irish corporate tax law, and the TCJA. “A case study of US MNCs in the information and communication technology (ICT) sector shows that under the revised structures the use of technology in international markets is no longer licensed from jurisdictions such as Bermuda and the Cayman Islands but instead is licensed directly from the United States,” Coffey concludes. “This is in line with the economic footprint of these companies and aligns the reporting of their profits with the location of their substance.”[20]

“Stuck” Profits

Though FDII may be a reasonable incentive not to shift future profits away, and even to return some intangibles to the U.S., it is not nearly sufficient to fix all profit-shifting ills. One of the largest problems with the current tax system, from the U.S. perspective, is that some older tax structures that predate the OECD’s project or the TCJA will be hard to unwind. The future stock of intangibles may be allocated in a manner more friendly to the U.S., but many high-value intangibles owned by U.S. MNE groups today may remain domiciled in jurisdictions that were tax-friendly in the 2010s, even though that is misaligned with their substance. Future reforms may want to consider possibilities for returning existing assets to the U.S. for tax purposes.

Overall, stasis, rather than a reduction in profit shifting, seems to be the outcome of U.S. and OECD efforts thus far. The European Union Tax Observatory, an organization that generally characterizes profit shifting as a significant problem, shows in its Global Tax Evasion Report 2024 that global corporate tax revenue losses to tax havens rose dramatically throughout the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s, but have since “stagnated at about 10 percent” of total corporate revenues, since the beginnings of the OECD’s project and the passage of TCJA.[21] Whether this counts as a failure or a success is in the eye of the beholder.

In general, economists who have advocated measures to contain profit shifting have shown in their academic work that TCJA should be expected to curb profit shifting, but perhaps not to the degree that they would like.[22]

FDII as an Export Subsidy

One critique of FDII, made shortly after the TCJA passed Congress, is that it offers a lower rate to revenues derived from exports than the U.S. tax system offers to revenues derived from domestic sales. This, the argument goes, will draw a challenge from the World Trade Organization or some other forum and be declared an illegal export subsidy, forcing the U.S. to abandon it.[23]

In simultaneous negotiations with Congress and the OECD in recent years, the Biden administration proposed eliminating FDII, but Congress ultimately did not do so. Nonetheless, the OECD’s June 2023 list of “harmful tax practices” included FDII and noted it was “in the process of being eliminated”—something that the Biden administration could not fully promise without Congress’s cooperation.[24]

Whether FDII ends up being accepted or not in international law remains to be seen. However, a provision resembling FDII that offers a reduced rate to highly mobile income may be an important component of the U.S. tax landscape going forward.

Base Erosion and Anti-Abuse Tax

The base erosion and anti-abuse tax is the last major base erosion element of TCJA. It disallows the deductibility of certain “base erosion payments” for firms that use too many of them. Much like GILTI, it is an attempt to use formulas to identify firms that may be profit shifting, and apply a tax to them. But unlike GILTI, it has raised comparatively little revenue.[25] In fact, JCT notes that despite a scheduled increase doubling the BEAT tax rate, the BEAT raised about as little revenue in 2020 at a 10 percent rate ($1.9 billion) as it did in 2018 at a 5 percent rate ($1.8 billion). JCT notes that the average base erosion percentage has declined from 8.4 percent to 2.9 percent, hollowing out the BEAT base. This is a rough metric that divides base erosion payments by total deductions and determines whether a taxpayer must pay BEAT.[26]

A natural follow-up line of inquiry on BEAT is why the revenue remains so low. Evidently, firms are structuring themselves in ways that avoid paying BEAT. Are they, for example, simply eschewing base erosion payments and giving up on them as a means of earnings stripping entirely?

The best analysis and empirical evidence suggest not. Rather, firms may be relabeling and recategorizing payments in ways that avoid BEAT liability without necessarily paying any more tax.

Shortly after TCJA passed, tax scholars in the Minnesota Law Review suggested a variety of ways that TCJA provisions could be exploited, including BEAT. “Importantly, base erosion payments generally do not include payments for cost of goods sold,” they note. “If a foreign affiliate incorporates the foreign intellectual property into a product and then sells the product back to a U.S. affiliate, the cost of the goods sold does not fall within BEAT.”[27] In other words, they suggest laundering base erosion deductions, which would be disallowed under BEAT, as cost of goods sold (COGS) deductions. A U.S. firm may not be able to make base erosion payments directly, but it can make cost of goods sold payments to a foreign affiliate, which in turn makes base erosion payments to another foreign affiliate, sidestepping BEAT by completing base erosion payments before an entity in scope for BEAT touches the supply chain.

Though data on the inner workings of MNEs are limited, a group of accounting scholars examined data from related-party payments and concluded that “results suggest that firms reclassify below the line related-party payments to COGS to avoid the BEAT.”[28]

Given that BEAT’s problem is a fast-declining base, not its rate, the scheduled increase in BEAT to 12.5 percent starting in 2026 is unlikely to change its trajectory.

How Pillar Two May Change the Impacts of GILTI, FDII, and BEAT

As many foreign jurisdictions change their tax codes to comply with Pillar Two, the impacts of GILTI, FDII, and BEAT will also change.

Most critically, GILTI—which offers relatively generous tax credits for tax rates up to about the mid-teens—will find its revenue sources drying up. As Tax Foundation and JCT modeling exercises have shown, rising foreign taxes will significantly reduce the revenues of U.S. taxes on foreign income by entitling MNEs to larger foreign tax credits.[29] This drawback of Pillar Two would also be likely under any other system with foreign tax credits. As global rates go up, there is simply less profit left for U.S. shareholders and the U.S. treasury to split.

GILTI is not perfectly consonant with Pillar Two’s IIR but is in many respects stricter. However, it is less strict in that it allows blending across countries, rather than requiring country-by-country reporting. This makes it not quite as effective as an IIR at sniffing out and punishing low-tax countries, but substantially easier to comply with. Some MNEs can have dozens of subsidiaries in many different tax jurisdictions. Those subsidiaries may be present in dozens of countries, making country-by-country reporting onerous.

For FDII, Pillar Two will represent both an opportunity and a threat. As foreign tax rates rise, the U.S. may become a relatively more attractive destination for profit shifting, making up a considerable amount of the revenue lost to greater foreign tax credits.[30]

A firm with a substantial FDII deduction would have a tax rate close to Pillar Two’s 15 percent minimum, even before other possible tax credits are considered. If a firm has tax liability below 15 percent under Pillar Two’s rules, it may be assessed a tax penalty known as the undertaxed profits rule.

In general, a successful Pillar Two implementation will reduce the dispersion of tax rates among jurisdictions, making all base erosion measures somewhat less beneficial. However, they are unlikely to become entirely obsolete; countries will still compete on rates up to the 15 percent mark, and on incentives not offset by the Pillar Two regime’s minimum tax. If tax competition remains, then so too will profit shifting, and base erosion measures can still justify their existence.

In reforming GILTI, FDII, and BEAT in the coming years, lawmakers should consider what they got right: relatively generous terms for economic substance, relatively generous terms for intangibles retained domestically, and CFC rules for high-intangible income held abroad. However, lawmakers should take a second look at problems with the current system, find ways to reduce clutter, and avert conflicts with international tax and trade agreements, including Pillar Two.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe[1] Mihir Desai, C. Fritz Foley, and James R. Hines, “Domestic Effects of the Foreign Activities of U.S. Multinationals,” American Economic Journal (February 2009), https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.1.1.181.

[2] Daniel Bunn, Alan Cole, Alex Mengden, “Anti-Avoidance Policies in a Pillar Two World,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 17, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/global/base-erosion-profit-shifting-pillar-two/.

[3] Kari Jahnsen and Kyle Pomerleau, “Corporate Income Tax Rates around the World, 2017,” Tax Foundation, Sep. 7, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/global/corporate-income-tax-rates-around-the-world-2017/.

[4] Kari Jahnsen and Kyle Pomerleau, “Designing a Territorial Tax SystemA territorial tax system for corporations, as opposed to a worldwide tax system, excludes profits multinational companies earn in foreign countries from their domestic tax base. As part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the United States shifted from worldwide taxation towards territorial taxation. : A Review of OECD Systems,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 1, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/eu/territorial-tax-system-oecd-review/.

[5] Tax Foundation, “Worldwide Tax System,” https://taxfoundation.org/tax-basics/worldwide-taxation/.

[6] Alan Cole, “Interest Deductibility – Issues and Reforms,” Tax Foundation, May 4, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/interest-deductibility/.

[7] Alex Muresianu, “R&D Amortization Hurts Economic Growth, Growth Industries, and Small Businesses,” Tax Foundation, Jun. 1, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/rd-amortization-impact/.

[8] Daniel Bunn, Alan Cole, and Alex Mengden, “Anti-Avoidance Policies in a Pillar Two World,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 17, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/global/base-erosion-profit-shifting-pillar-two/.

[9] Daniel Bunn, “U.S. Cross-border Tax Reform and the Cautionary Tale of GILTI,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 17, 2021, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/gilti-us-cross-border-tax-reform/.

[10] Alan Cole and Cody Kallen, “Risks to the U.S. Tax Base from Pillar Two,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 30, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/global-minimum-tax-us-tax-base/.

[11] Cody Kallen, “Expense Allocation: A Hidden Tax on Domestic Activities and Foreign Profits,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 26, 2021, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/expense-allocation-rules-hidden-tax-foreign-profits/.

[12] Internal Revenue Service, “Guidance Under Sections 951A and 954 Regarding Income Subject to a High Rate of Foreign Tax,” https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/07/23/2020-15351/guidance-under-sections-951a-and-954-regarding-income-subject-to-a-high-rate-of-foreign-tax.

[13] Daniel Bunn, “U.S. Cross-border Tax Reform and the Cautionary Tale of GILTI,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 17, 2021, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/gilti-us-cross-border-tax-reform/.

[14] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Conference Agreement for H.R. 1, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Dec. 18, 2017, https://www.jct.gov/publications/2017/jcx-67-17/.

[15] Joint Committee on Taxation, “U.S. International Tax Policy: Overview and Analysis,” Mar. 19, 2021, https://www.jct.gov/getattachment/a7e1e4e1-f225-434e-a58b-072208f11cff/x-16-21.pdf.

[16] Daniel Bunn, Alan Cole, William McBride, and Garrett Watson, “How the Moore Supreme Court Case Could Reshape Taxation of Unrealized Income,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 30, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/moore-v-united-states-tax-unrealized-income/.

[17] Eric Toder, “The Potential Economic Consequences of Disallowing the Taxation of Unrealized Income,” Tax Policy Center, Oct. 11, 2023, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/potential-economic-consequences-disallowing-taxation-unrealized-income/full.

[18] Mihir Desai, C. Fritz Foley, and James R. Hines, “Domestic Effects of the Foreign Activities of U.S. Multinationals,” American Economic Journal (February 2009), https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/pol.1.1.181.

[19] Alex Mengden, “Patent Box Regimes in Europe, 2023,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 8, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/eu/patent-box-regimes-europe-2023/.

[20] Seamus Coffey, “The changing nature of outbound royalties from Ireland and their impact on the taxation of the profits of US multinationals – May 2021,” Ireland Department of Finance, Jun. 14, 2021, https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/fbe28-the-changing-nature-of-outbound-royalties-from-ireland-and-their-impact-on-the-taxation-of-the-profits-of-us-multinationals-may-2021/.

[21] EU Tax Observatory, “Global Tax Evasion Report 2024,” https://www.taxobservatory.eu//www-site/uploads/2023/10/global_tax_evasion_report_24.pdf.

[22] Kimberly Clausing, “Profit Shifting Before and After the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” National Tax Journal 73:4 (November 2018): 1233-1266, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3274827; Javier Garcia-Bernardo, Petr Janský, and Gabriel Zucman, “Did the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Reduce Profit Shifting by US Multinational Companies?,” National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2022, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w30086/w30086.pdf.

[23] Reuven Avi-Yonah and Martin Vallespinos, “The Elephant Always Forgets: US Tax Reform and the WTO,” University of Michigan Law & Econ Research Paper, Jan. 28, 2018, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3113059.

[24] OECD, “Harmful Tax Practices – Peer Review Results,” June 2023, https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/harmful-tax-practices-consolidated-peer-review-results-on-preferential-regimes.pdf.

[25] Joint Committee on Taxation, “U.S. International Tax Policy: Overview and Analysis,” Mar. 19, 2021, https://www.jct.gov/getattachment/a7e1e4e1-f225-434e-a58b-072208f11cff/x-16-21.pdf.

[26] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Background and Analysis of the Taxation of income Earned by Multinational Enterprises,” https://www.jct.gov/publications/2023/jcx-35r-23/

[27] David Kamin, David Gamage, Ari Glogower, Rebecca Kysar, Darien Shanske, Reuven AviYonah, Lily Batchelder, J. Clifton Fleming, Daniel Hemel, Mitchell Kane, David Miller, Daniel Shaviro, and Manoj Viswanathan, “The games they will play: Tax games, roadblocks, and glitches under the 2017 tax legislation,” Minnesota Law Review 103 (2018): 1439–1521, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3089423.

[28] Stacy Kelley LaPlante et al., “Just BEAT It: Do firms reclassify costs to avoid the base erosion and anti-abuse tax (BEAT) of the TCJA?,” Singapore Management University School of Accountancy, Feb. 1, 2021, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3784739.

[29] Alan Cole and Cody Kallen, “Risks to the U.S. Tax Base from Pillar Two,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 30, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/global-minimum-tax-us-tax-base/.

[30] Alan Cole and Cody Kallen, “Risks to the U.S. Tax Base from Pillar Two,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 30, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/global-minimum-tax-us-tax-base/.

Share this article