Related Research

Key Findings

- Connecticut is struggling. The state is affluent, but a shrinking population and departing employers, coupled with mounting costs of government and the high taxes that pay for it, have the state headed in the wrong direction.

- The state’s high and economically inefficient taxes are only one of several reasons for the outmigration of people and jobs, but taxes are an important consideration and one within policymakers’ power to address.

- In addition to its high rate, Connecticut’s volatile corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. suffers from its inclusion of an alternative capital stock base and limitations on the utilization of net operating losses. The state’s recent shift to unitary combined reporting can also raise both taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. and compliance costs for some businesses.

- The individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. has grown far beyond the expectations set when it was first implemented in 1991, and its structure, in tandem with the unique economic characteristics of Connecticut’s population, result in substantial revenue instability.

- Like most states, Connecticut exempts broad swaths of personal consumption from the sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. . Broadening the tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. could pay down substantial reforms to other taxes, as could the use of newfound authority to tax remote sales.

- The absence of a de minimis threshold for business tangible property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services. liability imposes substantial compliance costs on many businesses while yielding a negligible amount of additional revenue for local governments.

- Keeping faith with an electorate which adopted a spending cap alongside the authorization of an individual income tax requires properly implementing and abiding by the cap.

- With businesses and individuals heading for the exits, policymakers cannot afford complacency.

Introduction

Connecticut’s population is shrinking. From year to year the decline is not dramatic, but the trend is there—and the effects are beginning to be felt. They have been noticed, too: in 2017, The Atlantic asked, “What on Earth Is Wrong with Connecticut?”[1] At Slate, it was “Something has gone wrong with Connecticut.”[2] The Hartford Courant is keeping tabs on the number of billionaires leaving the state.[3] Business journals are fretting about sustained outmigration.[4] Even the state itself is getting into the act, producing a 2017 study on population and migration trends.[5]

That migration is not limited to people: companies are leaving, too. While CVS Health’s acquisition of Aetna kept the company–which had planned a relocation to New York City–in Hartford,[6] there was no such reprieve with General Electric or Alexion Pharmaceuticals, both of which decamped to Boston.[7] Corporations headquartered elsewhere, like Caterpillar, Motorola, and Kraft Heinz, reduced the size of their Connecticut workforces—and that’s just the companies that shifted jobs to one city, Chicago.[8] The biggest companies garnered the most headlines, but for every General Electric or Alexion, there are many more small businesses that have pulled up stakes.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeThese companies did not relocate to the Sun Belt. That might have been worrying enough. Instead, companies are being pulled toward New York City, Boston, and Chicago. For some, taxes are the clear culprit, with proponents of this theory pointing to the statements of companies and individuals making their exodus. For others, taxes are at most incidental to the main story, particularly given that Boston and New York City are not exactly known as oases of low taxation.

The truth, as is often the case, likely lies somewhere in between. High (and rising) tax burdens have contributed to stagnation. So has the revitalization of major urban centers. So, too, have broader economic and demographic trends, greater mobility, and a shift in the entrepreneurial center of gravity in the country.

Younger workers increasingly want to move back into the cities their parents and grandparents abandoned for the suburbs. Lifestyles have changed; industry balances have shifted. Connecticut can address some of these problems, but not all. What it can do, though–what it must do–is make its tax code more competitive.

Taxes, after all, are within policymakers’ authority in a way that the weather, or the rising appeal of big cities, really aren’t. Cities and states with enough cachet can often thrive despite high costs of living, including high tax costs, but states that are losing ground enjoy no such luxury. If policymakers wish to arrest the outmigration of jobs and people to more welcoming climes, they will need to do something about a tax code that increasingly penalizes those who might otherwise be inclined to stay.

Connecticut’s Economy

At $70,121, Connecticut has the highest per capita income of any state in the country[9]—an unusual preface to a tale of a state in a snowballing fiscal crisis. Nor does the state lack for resources, at least by conventional measures: Connecticut has the third-highest state and local tax collections per capita, at $7,410 per person.

As a wealthy state, Connecticut receives less federal funding than average, since fewer residents are beneficiaries of state-administered programs with federal funding sources.[10] Therefore, while the state’s $7,410 per capita tax collections is substantially higher than the national average of $4,875, its total revenue per capita of $9,121 is just slightly above the national average. This should, however, also come with fewer demands on that revenue, since higher levels of federal assistance typically imply substantial low-income populations which create additional financial pressures on the state treasury as well.

But Connecticut has historically prioritized relatively high provision of government services. Generous public pensions, meanwhile, are beginning to catch up with the state, particularly as the population declines. Some of the traditional engines of economic activity in Connecticut are slowing, and in some cases businesses and individuals are going elsewhere.

The state benefits from a strong manufacturing base and an educated workforce. Its geography is advantageous for multinational firms which require an East Coast presence but not a big city headquarters. For many years, it has proven an attractive alternative to New York City and Boston. Increasingly, however, the state is struggling. Connecticut’s high and distortive taxes are part of the problem, and their reform can be part of the solution.

Corporate Taxes

Connecticut’s corporate tax has two components: a traditional tax on net income and an alternative minimum tax on net assets. Businesses pay the greater of 7.5 percent of net income (no cap) or 3.1 mills on the value of their capital stock up to a cap of $1 million in capital stock tax liability. Companies with at least $100 million in gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total of all income received from any source before taxes or deductions. It includes wages, salaries, tips, interest, dividends, capital gains, rental income, alimony, pensions, and other forms of income. For businesses, gross income (or gross profit) is the sum of total receipts or sales minus the cost of goods sold (COGS)—the direct costs of producing goods, including inventory and certain labor costs. also face a surtaxA surtax is an additional tax levied on top of an already existing business or individual tax and can have a flat or progressive rate structure. Surtaxes are typically enacted to fund a specific program or initiative, whereas revenue from broader-based taxes, like the individual income tax, typically cover a multitude of programs and services. of 10 percent, down from 20 percent prior to 2018.[11]

Corporate Net Income and Capital Stock Taxes

Imagine a company with $20 million in net assets and $3 million in net taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. Taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. . This company would owe $225,000 in corporate income taxes under the net income calculation and $62,000 under the capital stock calculation, so the company would remit the higher of the two ($225,000). If, however, the next year the company posted a loss, it would still face positive tax liability, now paying against its assets. This illustrates one of the shortcomings of capital stock taxes: they are levied without regard to ability to pay, imposing burdens even when a business is losing money.

Capital stock taxes are also nonneutral, as different industries and business structures have vastly different asset mixes. Finally, capital stock taxes penalize investment and expansion. Most established, profitable companies in Connecticut have little reason to be concerned with the state’s capital stock tax, since it functions as a minimum tax within the corporate income tax, but new and expanding companies can be penalized by it, as can businesses that are struggling to survive. The tax favors the status quo to the detriment of less established businesses, and thus holds back Connecticut’s economy.

Meanwhile, the surtax, while applicable to very few businesses, imposes an unusually high corporate rate on some of the state’s largest employers. At 10 percent, the surtax brings the corporate net income tax rate to 8.25 percent for businesses with more than $100 million in gross income, which is on the high side nationally, though about in line with regional peers.

Net Operating Loss Provisions

Connecticut’s net operating loss provisions are slightly less generous than those of many peer states. Although corporate income tax liability is determined on an annualized basis, business cycles do not follow the calendar. This can be problematic for corporations with cyclical income, enjoying high profitability one year and losses the next. To mitigate this reality, states (along with the federal government) allow corporations to deduct losses from previous and future years to offset current taxes owed. These net operating loss (NOL) “carrybacks” and “carryforwards” smooth out tax obligations over time, ensuring that industries with cyclical income are not at a competitive disadvantage against industries with more consistent and stable revenue streams.

Under a well-designed system of net operating losses, businesses which experience a period of negative income but return to profitability have the opportunity to deduct their losses against future taxable income. The NOL deduction helps ensure that, over time, the corporate income tax is a tax on average profitability. Without the NOL deduction, corporations in cyclical industries pay much higher taxes than those in stable industries, even assuming identical average profits over time.

There are two important variables of a state’s NOL provisions: the number of years allowed for carrybacks and carryforwards, and caps on the amount of carrybacks and carryforwards. The maximum that any state allows for carrybacks is three years, with no cap (that is, an unlimited dollar amount allowed up to the entirety of current year taxable income). Among the states that allow carrybacks, the most common time span is two years with no cap. Most states offer a 20-year uncapped carryforward, and under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the federal government now permits losses to be carried forward indefinitely but limits them to 80 percent of pre-NOL taxable income.

Connecticut disallows net operating loss carrybacks. Furthermore, while the state permits a 20-year carryforward, the deduction is limited to 50 percent of net income in any given year. Among neighboring states, New York has 20-year uncapped carryforwards and a three-year uncapped carryback period, and Massachusetts offers 20-year uncapped carryforwards but no carrybacks. Neighboring Rhode Island has an uncommonly stingy approach to net operating losses, only permitting them to be carried forward for five years.

Unitary Combined Reporting

Since 2016, Connecticut has mandated unitary combined reporting for corporations, requiring companies with common ownership that are engaged in a unitary business to calculate their tax liability on a combined basis.[12] Functionally, this means that all related businesses are treated as a single entity for tax purposes, rather than filing separately.

Taxing all affiliated businesses as if they constitute a single legal entity is designed to undermine tax planning, where companies shift income to some subsidiaries and park losses in others to minimize tax exposure. Opponents point to high compliance costs, increased complexity, and taxation of legitimate business activity in no way associated with the state or not otherwise subject to corporate taxes.

Unitary combined reporting shifts tax liability among related firms in ways that have no connection to ability to pay. It assumes that all member companies have the same level of profitability per dollar of sales, an assumption which cannot be borne out in the real world. Just because two companies are affiliated does not mean that each entity is in similar shape financially; increasing the tax burden on one company, which may be struggling, because a related company elsewhere is doing well, can be economically devastating.

Where differences in profitability are the result of tax planning, those strategies can be adjusted; where, as is more often the case, they represent the actual financial standing of each company, splitting tax liability this way can be uniquely burdensome for some operations.

The challenges associated with combined reporting do not end–or even begin–with an inequitable distribution of tax burdens. The first step is calculating that tax liability, which can be complex, costly, and controversial under combined reporting. There is often no easy answer to the question of which affiliated businesses should be considered as part of the unitary group; in fact, answers to this definitional question can vary from state to state and even year to year, meaning that just because a company is already subject to combined reporting in other states does not mean that Connecticut’s requirements create no additional burden.[13] Disputes can take years or even decades to untangle. In 2010, California (which used combined reporting) was still processing tax cases from the 1970s, and General Electric had just closed its 1982 California tax return.[14]

Combined reporting increases complexity and can misallocate tax burdens. Statistical analyses demonstrate that combined reporting reduces gross state product.[15] Expectations of higher state revenue, meanwhile, have not always panned out. [16]

Other Issues in Corporate Taxation

Revenue volatility is a frequent complaint in Connecticut, and the state’s reliance on a high-rate corporate income tax contributes to that revenue uncertainty. Since 2008, 16 states and the District of Columbia have cut corporate income taxes.[17] Reductions in corporate rates elsewhere reflect a trend toward decreased reliance on the highly volatile tax, which is imposed on an ever-declining amount of taxable income. Furthermore, a number of states have undertaken efforts to simplify the tax structure by broadening the base and lowering the rate. Corporate income tax revenue is in decline across the country as more businesses choose to structure as S corporations and limited liability corporations (LLCs), single sales factor apportionmentApportionment is the determination of the percentage of a business’s profits subject to a given jurisdiction’s corporate income tax or other business tax. US states apportion business profits based on some combination of the percentage of company property, payroll, and sales located within their borders. schemes become more common, and states give away more of their tax base in special credits and deductions.

Like most states, Connecticut relies on tax incentives to reduce liability for select industries and economic activities. Some of the state’s business tax credits have unlimited carryforward periods, while others are capped, most frequently at five years of carryforwards.[18] Tax incentives are a patch for an otherwise uncompetitive tax code, and Connecticut policymakers should explore paring back incentives in exchange for rate reductions or other structural reforms. They should not, however, reduce the value of credits already issued by further limiting their carryforward periods or otherwise capping claims, as this constitutes retroactive taxation.

Corporate income taxes tend to be complex and impose substantial administrative burdens for both payers and the government, and this complexity has not abated as the tax base has eroded. Finally, revenue volatility necessarily follows from the nature of the tax, since in periods of economic distress, many companies may post losses and thus be exposed only to the capital stock portion of the tax—significant for some, but negligible for others. As such, collections tend to be highly unstable, spiking sharply in good years and collapsing in bad ones.

Individual Income Taxes

Connecticut’s individual income tax is of a recent vintage. Implemented in 1991, it is the newest state income tax in the country. Touted as a way to diversify the state’s revenue stream and take the pressure off other taxes, it has expanded at a rapid clip and accounts for a far larger share of the state’s total collections than was originally envisioned.

Connecticut’s individual income tax has a top rate of 6.99 percent, which is above the national average, and it is imposed on a broad base of income. State income tax collections consume 3.05 percent of personal income in the state, a percentage only exceeded by five states and the District of Columbia. Collections per dollar of personal income are about 41 percent higher than the national average, reflecting the state’s above-average top rate and broad definition of taxable income.[19] As a wealthy state, Connecticut also sees an above-average share of state income exposed to the top rate.

Adopted as a way to improve revenue stability, it has proved the opposite.[20] Capital gains are a significant source of income for high earners, but investment income is inherently volatile. A graduated-rate tax in a high-income state results in heavy reliance on income streams which may change sharply from year to year. Capital gains are taxed upon realization, meaning that taxes are only owed once an asset is sold. They are, moreover, offset by capital losses, and in some years, many more people will be cutting their losses than taking their gains.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeNationally, capital gains realizations soared 91 percent in the tax reform year of 1986, then plummeted 55 percent the next year.[21] They slid 71 percent between 2007 and 2009, during the Great RecessionA recession is a significant and sustained decline in the economy. Typically, a recession lasts longer than six months, but recovery from a recession can take a few years. . They slipped 55 percent in 1987 and 46 percent in 2001.[22] Other sources of tax revenue showed volatility in these years as well, but at nowhere near the intensity of capital gains.

Capital gains are taxed upon realization, meaning that you only owe the tax once you sell the asset. And of course, capital gains are offset by capital losses. In some years, many more people will be cutting their losses than taking their gains.

Connecticut acknowledges this problem, which served as the motivation for the state’s volatility cap. Recognizing that a sizable share of capital gains income is reported by individuals who file quarterly returns, the state set a $3.15 billion cap on collections from quarterly filers and sweeps any additional amounts into the budget reserve fund, part of which can be transferred to help pay down unfunded pension liabilities.[23] This policy represents a meaningful step in the right direction, but can only partially remedy the tax’s underlying instability.

Revenue stability can also be undermined if people choose to vote with their feet. Taxes are only one of many factors in deciding where to live and work, but especially for high-income taxpayers–who enjoy greater mobility–an uncompetitive individual income tax has the potential to drive people away faster than the state can attract new residents.

In fiscal year 2016, more than 82,000 people left for another state, while 63,000 moved to Connecticut from another state, representing a net outflow. Even more significantly, however, the newcomers of fiscal year 2016 had a cumulative adjusted gross income (AGI) of $3.2 billion, while those departing had a cumulative AGI of $5.8 billion. This represents a net loss of $2.6 billion of AGI from departures that year alone. [24]

Initially a 4.5 percent single-rate tax,[25] the individual income tax’s rate structure has changed five times since the income tax’s adoption in 1991.[26] The tax became a graduated rate tax in 1996, but its current status as a highly progressive income tax only dates to 2009. When the state first shifted from a flat income tax to a two-rate tax, the former flat rate was adopted as the new flat rate (on income above $10,000), making the change a small net tax cut. The top rate crept up to 5 percent in 2003, but it was not until 2009 that the tax’s character changed, with a new top rate of 6.5 percent on income above $500,000.

Two tax increases later, 6.5 percent is the rate on income between $200,001 and $250,000, while the top rate stands at 6.99 percent. All income above $10,000 is taxed at higher rates than it was under the initial 4.5 percent flat-rate tax.[27] The income tax had expanded to include seven brackets by 2015.

| Year | Top Rate | Kick-In of Top Rate | Brackets |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Source: Connecticut Office of Legislative Research |

|||

| 1991 | 4.50% | $0 | 1 |

| 1996 | 4.50% | $2,250 | 2 |

| 1997 | 4.50% | $6,250 | 2 |

| 1998 | 4.50% | $7,250 | 2 |

| 1999 | 4.50% | $10,000 | 2 |

| 2003 | 5.00% | $10,000 | 2 |

| 2009 | 6.50% | $500,000 | 2 |

| 2011 | 6.70% | $250,000 | 6 |

| 2015 | 6.99% | $500,000 | 7 |

Aggressive increases in recent years contribute to a sense that the state’s desire for additional revenue is insatiable. In conversations with leaders of traditional C corporations, we found that the individual income tax was cited frequently as a consideration for businesses making location decisions. Even though the businesses themselves pay corporate, not individual, income taxes, the individual income tax drives up the cost of living in Connecticut and makes the state less attractive overall.

The last budget adopted prior to the adoption of an individual income tax ran $7.15 billion.[28] In the fiscal year 2019 budget, total appropriations reached $20.86 billion.[29] Had Connecticut’s budget merely kept pace with inflation, appropriations would stand at $13.67 billion. Instead, state spending burgeoned, driven in large part by an expanding individual income tax.

Once championed as a way to diversify revenue sources and reduce volatility, with additional revenues as a secondary consideration, the income tax has transformed Connecticut’s budget through a dramatic expansion in revenue capacity. Unfortunately for taxpayers, even this remarkable rate of revenue growth has proven incapable of keeping up with the demands of an ever-costlier state government.

Sales Tax

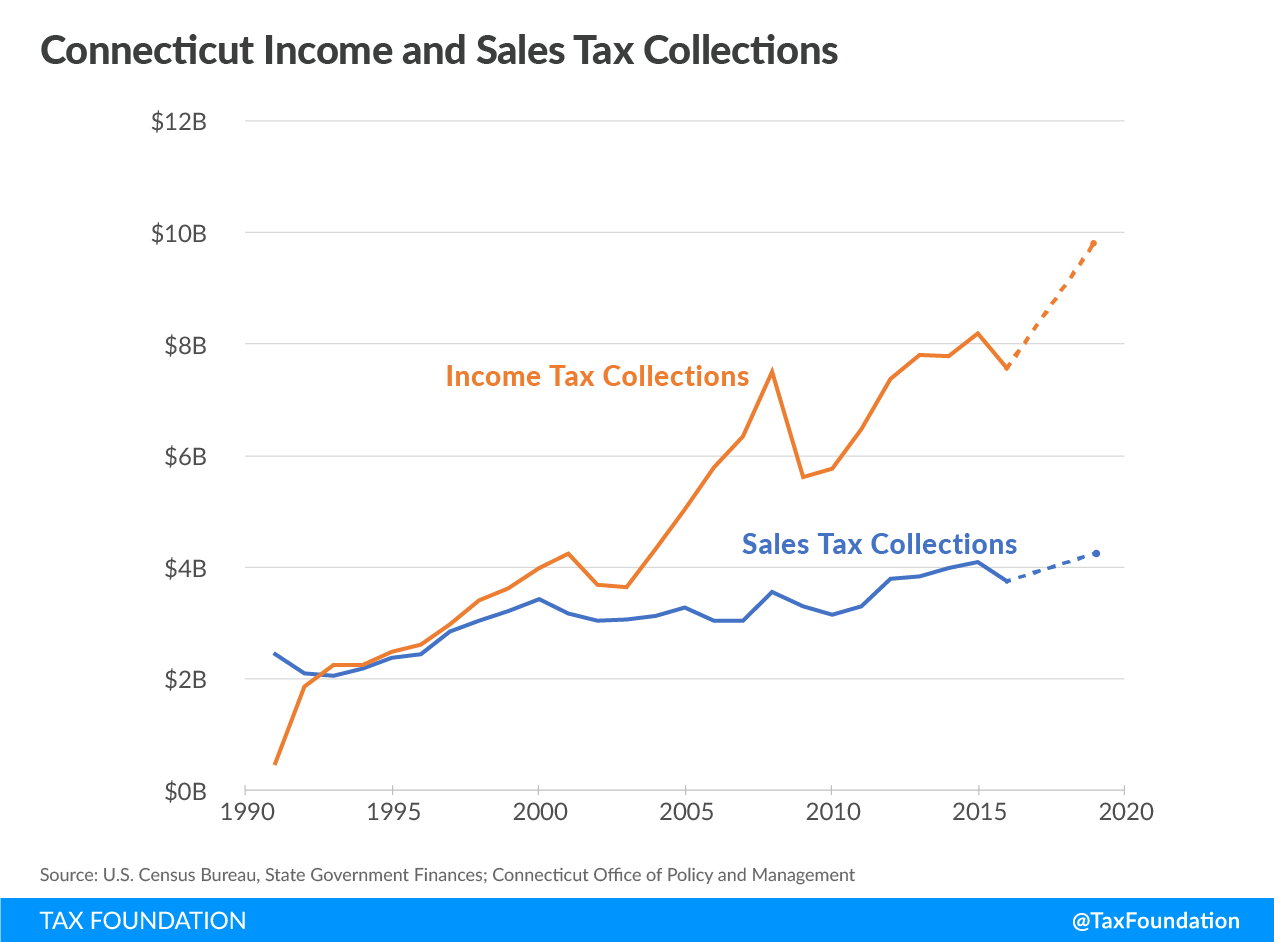

First adopted in 1947, the sales tax long held pride of place as Connecticut’s most important source of tax revenue. As the state’s spending soared, the sales tax rate peaked at 8 percent in 1989,[30] which helped build support for the adoption of an individual income tax in 1991. The sales tax rate was rolled back to 6 percent, and the new income tax initially yielded slightly less revenue than the 6 percent sales tax. Changes to the income tax since then, however, have caused the two taxes to diverge sharply, and today the income tax raises more than twice as much as the sales tax.

If the sales tax were still at 8 percent, it would raise an additional $1.06 billion each year. The income tax that occasioned the rate reduction generates $9.86 billion a year.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeOne of the great advantages of the sales tax is its stability. All tax revenue is subject to economic cycles, but consumption taxes experience considerably less volatility than income taxes. Over time, however, Connecticut’s sales tax base has eroded as the economy becomes increasingly service-oriented. Lawmakers have also carved certain goods out of the sales tax for policy reasons.

The exemption for groceries, for instance, reduces collections by an estimated $451 million each year. The prescription drug exemption costs $412 million, while the state forgoes another $31 million by exempting nonprescription drugs.[31] Most services go untaxed by default, as the state tax base includes tangible goods unless otherwise exempted, but only includes such services which are directly mentioned in statute.

Accordingly, the state does not provide estimates for the exclusion of many services from the base. However, a first-order estimate of amount forgone by not taxing personal services alone is $150 million.[32] The following table delineates just a few of the major exemptions within the sales tax code, together worth $2 billion in forgone revenue. To place the magnitude of these exemptions in context, if they were included in the base, the sales tax would raise the same amount of revenue with a 4.3 percent rate as it currently does at a 6.35 percent rate.

| Good or Service | Amount |

|---|---|

|

* Author’s estimate. Sources: Office of Fiscal Analysis; Bureau of Economic Analysis; author’s calculations (personal services category). |

|

| Food | $450.8 million |

| Prescription Drugs | $411. 8 million |

| Motor Fuel | $411.7 million |

| Patient Care Services | $382.9 million |

| Consumer Utilities | $156.1 million |

| Personal Services* | $150.6 million |

| Nonprescription Drugs | $30.8 million |

| Amusement and Recreation | $12.3 million |

| Total | $2.01 billion |

The Supreme Court’s decision in Wayfair v. South Dakota, eliminating physical presence as a requirement for collecting sales taxes on transactions involving out-of-state sellers,[33] gives states new opportunities to collect additional revenue as well. However, the size of this windfall should not be overestimated. The federal General Accountability Office provides low- and high-end estimates of potential revenue gains through remote sales tax collection authority, giving Connecticut a range from $128 to $194 million.[34] For simplicity’s sake, this paper will use a midpoint estimate of $161 million, but this figure–as with estimates from sales tax base broadening–should be considered a rough estimate only. Adding remote sales authority to the above base-broadeners would be enough to permit a revenue-neutral 4.2 percent rate.

Connecticut does not, however, need a 4.2 percent sales tax rate. (Earlier this year, a state tax commission recommended raising the sales tax rate from 6.35 to 7.25 percent to help pay down reforms elsewhere in the code.[35]) What it needs is reforms to other elements of the tax code, and sales tax base-broadening can help pay down rate reductions and reforms elsewhere. If Connecticut wanted to restore its old 6.0 percent sales tax rate, this could be accomplished with about $289 million in base-broadeners; any revenue beyond that could be put toward other reforms.

Property and Wealth Taxes

Business Tangible Property Taxes

Connecticut’s property taxes extend to both real and tangible personal property. Real property includes land, buildings, improvements, fixtures, minerals, and other property attached to the land itself, including rights and interests. Tangible personal property encompasses other physical objects, including business equipment—often colloquially defined as property that can be touched and moved. In Connecticut, household goods are exempt from the tangible personal property tax, and automobiles are taxed separately, rendering the tangible personal property tax primarily a tax on machinery and equipment (except when used in manufacturing), trade fixtures, and even some software owned by businesses.

Connecticut has reduced its reliance on tangible personal property taxes over the years, adopting exemptions for inventory and manufacturing machinery and equipment. These reforms are part of the reason why personal property taxes declined from 14.3 to 5.5 percent of the property tax base from 1991 to 2013.[36]

Several of Connecticut’s regional competitors forgo tangible personal property taxes. New York, Pennsylvania, and New Hampshire exempt tangible personal property, while collections in Vermont are minimal.[37] This gives businesses in those states an advantage over their Connecticut-based competitors, as tangible personal property taxes reduce capital investment.

In addition to the actual tax burden, tangible personal property taxes impose substantial compliance and administration costs because the tax levy is “taxpayer active.” This means that businesses must fill out forms identifying all of their personal property subject to taxation and detailing relevant attributes including, but not limited to, a physical description, the year of purchase, the purchase price, and any identifying information (e.g., serial numbers). The tax is to be remitted upon the depreciated value of each article of personal property.[38]

The direct and indirect costs of tangible personal property taxes have made such taxes a target for reduction or elimination in a growing number of states, as they are a barrier to economic growth. According to the Council on State Taxation, nearly 34 percent of state and local business taxes remitted in Connecticut are property taxes (almost four times as much as is paid in corporate income taxes),[39] and nearly a quarter of it ($590 million a year) is due to personal property taxes.[40] A direct tax on capital formation, tangible personal property taxes are also distortionary, as they apply to some business inputs but not to others. Taxes and machinery and equipment create incentives for mobile capital to flow out of high-tax areas into low-tax areas.

Removing manufacturing machinery and equipment from the base was an important step, but the state should have the ultimate goal of repealing this uncompetitive tax. In the interim, Connecticut policymakers have several options for tangible personal property tax reform.

The state could gradually reduce reliance on tangible personal property taxes by creating a de minimis exemption. Simply exempting taxpayers with $10,000 or less in taxable personal property would eliminate liability for 46 percent of current taxpayers at a cost of 0.014 percent of property tax revenue. The costs of compliance and collections are far too high to justify collecting such a negligible amount of revenue.[41] Setting a higher threshold, such as $200,000 in assessed value, would exempt almost 93 percent of current filers while retaining 88.5 percent of the tax base.[42]

The state could also phase out the tax over time by exempting new property from taxation, as Maine and Kansas have done.[43] This has the advantage of limiting the immediate impact on local bases, while at the same time encouraging economic growth by keeping new and expanding business from entering the system in the future. Over time, taxable old equipment is replaced with new equipment that is exempt from the tax, while local governments avoid steep and sudden reductions in tax revenue, instead relying on gradual cuts that could be absorbed by real property or other taxes over time without large rate increases.

Estate Tax

Connecticut is one of 13 states which levies an estate taxAn estate tax is imposed on the net value of an individual’s taxable estate, after any exclusions or credits, at the time of death. The tax is paid by the estate itself before assets are distributed to heirs. , and one of 18 states with some sort of tax on transfers at death.[44]

Until recently, the federal government provided a credit against state death taxes paid (CSDT), up to a certain amount. Consequently, all 50 states adopted estate taxes designed, at the very least, to capture all revenue up to this threshold (commonly called the “pick-up tax”), since they could do so without increasing anyone’s tax liability. With the elimination of the credit, most states have repealed their estate taxes—some immediately, and some in the intervening years. Connecticut remains one of a dwindling number of holdouts.[45]

In recent years, Connecticut’s nine-bracket estate tax, with rates ranging from 7.2 to 12 percent, has yielded above-average burdens on estates valued at less than $5 million, but below-average burdens for the largest estates. The state is currently phasing in conformity with the federal exemption level, however, which will ultimately exempt from taxation all estates valued under $11.2 million.

This reform will eliminate liability for most taxpayers currently subject to the estate tax, and will make compliance and administration easier by mirroring federal law. Even a tax limited to the largest of estates, however, can have detrimental economic effects, as it can encourage tax avoidance activities or even drive wealthy older taxpayers out of state, potentially depriving the state of income tax and other tax collections (and broader economic activity) in their final years.

Spending Cap

Since 1991, Connecticut’s constitution has imposed a spending cap, ratified by the voters in tandem with the individual income tax. Ostensibly, the cap prohibits the state budget from increasing faster than the percentage increase in personal income or inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. (whichever is higher), subject to supermajority overrides or an emergency finding by the governor. In practice, however, the requirement is largely ineffectual, with the legislature and governor repeatedly redefining the base for the authorized budget or leaning on enabling legislation to exclude elements of the budget from the capped general budget expenditures.[46] And now, according to the Office of the Attorney General, the cap is not only ineffectual but unenforceable.[47]

The constitutional amendment requires that the General Assembly define the terms “increase in personal income,” “increase in inflation,” and “general budget expenditures” in statute, all of which are necessary to the operation of the cap. Prior to the amendment’s ratification, the legislature adopted a stopgap statutory spending cap, but never proceeded to adopt legislation defining terms for the new constitutional requirement. Accordingly, the Attorney General contends that the constitutional cap is not in operation, and that while the statutory cap also imposes a supermajority requirement, it is legally unenforceable, and could be suspended by a simple majority vote.[48]

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribePrevious Attorneys General came to a different conclusion, opining that the statutory caps provided the required definitions for purposes of the constitutional amendment.[49] Policymakers have long evaded the cap by shifting costs outside it, but under the new interpretation, they are spared even this hurdle. When voters ratified an income tax and a spending cap side-by-side, it is reasonable to assume that they wanted real spending restraint. Instead, they got a nearly toothless measure, and now no constraint at all. Maintaining faith with the public requires fixing the spending cap.

Conclusion

Connecticut has failed to live up to the expectations of 1991. Changes intended to make tax collections more stable, combined with constraints intended to promote fiscal prudence, have strayed far wide of the mark. In recent years, policymakers have pursued a range of tax hikes which have created uncertainty and undermined the state’s competitiveness, without addressing structural shortcomings which become more pronounced with time. The time has come to rebalance and restructure the tax code, and perhaps to cast a more critical eye upon the rising expenditures that helped bring the state to this point.

There will be hard choices. But as the state’s finances falter and its people and businesses look for the exits, the status quo is no choice at all.

Notes

[1] Derek Thompson, “What on Earth is Wrong With Connecticut?” The Atlantic, July 5, 2017, https://theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/07/connecticut-tax-inequality-cities/532623/.

[2] Henry Grabar, “Trouble in America’s Country Club,” Slate, June 2, 2017, http://slate.com/articles/business/metropolis/2017/06/something_is_wrong_with_connecticut.html.

[3] Dan Haar, “Two Billionaires Head For Florida, Deepening CT’s Cash Crisis,” Hartford Current, March 3, 2016, http://courant.com/business/dan-haar/hc-haar-forbes-list-thomas-peterffy-exit-costs-state-20160302-column.html; Russell Blair, “Forbes: Connecticut Retains Its 17 Billionaires,” Hartford Courant, March 7, 2018, http://courant.com/politics/hc-pol-no-billionaires-left-connecticut-20180307-story.html.

[4] HartfordBusiness.com, “CT Fourth Highest State in Out-Migration,” Jan. 4, 2018, http://hartfordbusiness.com/article/20180104/NEWS01/180109967/ct-fourth-highest-state-in-out-migration.

[5] Manisha Srivastava, “Connecticut’s Population and Migration Trends: A Multi-Data Source Dive,” Connecticut’s Office and Policy and Management, May 2017, http://ct.gov/opm/lib/opm/budget/resourcesanddata/CTs_Population_and_Migration_Trends.pdf.

[6] Jon Chesto, “CVS Health Confirms that Aetna Will Stay in Hartford,” Boston Globe, Jan. 12, 2018, https://bostonglobe.com/business/2018/01/12/cvs-health-confirms-that-aetna-will-stay-hartford/KhNHIzNDG455v5Nt9QgyEI/story.html.

[7] Stephen Singer, “General Electric Moving Headquarters to Boston,” Hartford Courant, Jan. 13, 2016, http://courant.com/business/hc-boston-ge-moving-20160113-story.html; Stephen Singer, “Alexion Exits New Haven For Boston, Agrees To Repay Millions In State Aid,” Hartford Courant, Sept. 12, 2017, http://courant.com/news/connecticut/hc-alexion-moving-new-haven-boston-20170911-story.html.

[8] Henry Grabar, “Trouble in America’s Country Club.”

[9] This is true of states, though the District of Columbia posts a higher per capita income ($76,986). Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Regional Economic Accounts, SA1 Personal Income Summary: Personal Income, Population, Per Capita Personal Income,” https://www.bea.gov/regional/.

[10] States receive block grants or partial federal matches for many expenditures, Medicaid perhaps most notably. Not all federal grants are for low-income individuals, however, or for individuals at all; for instance, states receive highway dollars from the federal government as well.

[11] Connecticut Commission on Fiscal Stability and Economic Growth, “Final Report,” March 2018, 27-28, https://www.cga.ct.gov/fin/tfs/20171205_Commission%20on%20Fiscal%20Stability%20and%20Economic%20Growth/20180301/Final%20Report%20with%20Appendix.pdf.

[12] PricewaterhouseCoopers, “Connecticut – Guidance on unitary combined reporting requirements,” March 2, 2016, 1, https://www.pwc.com/us/en/state-local-tax/newsletters/salt-insights/connecticut-guidance-on-unitary-combined-reporting-requirements.html.

[13] William F. Fox and LeAnn Luna, “Combined Reporting with the Corporate Income Tax: Issues for State Legislatures,” Center for Business and Economic Research, University of Tennessee, November 2010, iv.

[14] Commonwealth Foundation, “Pennsylvania Budget Facts 2010: Corporate Taxes,” June 29, 2010, https://www.commonwealthfoundation.org/research/detail/pennsylvania-budget-facts-2010-corporate-taxes.

[15] William F. Fox and LeAnn Luna, “Combined Reporting with the Corporate Income Tax: Issues for State Legislatures,” 36-40.

[16] William F. Fox, LeAnn Luna, Rebekah McCarty, Ann Boyd Davis, and Zhou Yang, “An Evaluation of Combined Reporting in the Tennessee Corporate Franchise and Excise Taxes,” Report to the Tennessee Comptroller of the Treasury, Oct. 30, 2009, 35, http://cber.haslam.utk.edu/pubs/combrpt.pdf.

[17] See Joseph Bishop-Henchman, “Trend #3: Corporate Tax Reductions, Top 10 State Tax Trends in Recession and Recovery, 2008 to 2012,” Tax Foundation, June 13, 2012, http://taxfoundation.org/article/trend-3-corporate-tax-reductions; Facts & Figures: How Does Your State Compare? Tax Foundation, multiple years.

[18] Rute Pinho, “Guide to Connecticut’s Business Tax Credits,” Connecticut Office of Legislative Research, Dec. 11, 2017, 23, https://cga.ct.gov/2017/rpt/pdf/2017-R-0287.pdf.

[19] Author’s calculations using U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis data.

[20] Editorial, “25 Years After Reviled Income Tax Came In, CT Is Hooked On It,” Hartford Courant, Aug. 12, 2016, http://www.courant.com/opinion/editorials/hc-ed-income-tax-still-riles-25-years-later-20160811-story.html.

[21] Congressional Budget Office, “Capital Gains Taxes and Federal Revenues,” Revenue and Tax Policy Brief, Oct. 9, 2002, 3, https://cbo.gov/sites/default/files/107th-congress-2001-2002/reports/taxbrief2.pdf.

[22] Congressional Budget Office, “Budget and Economic Data,” https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#7.

[23] Rute Pinho, “OLR Backgrounder: Connecticut’s Volatility Cap,” Connecticut Office of Legislative Research, Jan. 29, 2018, https://cga.ct.gov/2018/rpt/pdf/2018-R-0041.pdf.

[24] U.S. Census Bureau, “State to State Migration Flows,” https://census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/geographic-mobility/state-to-state-migration.html.

[25] Rute Pinho, “Connecticut Income Tax Rates and Brackets Since 1991,” Connecticut Office of Legislative Research,” June 14, 2018, https://www.cga.ct.gov/2018/rpt/pdf/2018-R-0058.pdf.

[26] In 1996, when the single-rate tax was first transformed into a two-rate graduated income tax, the threshold for the second bracket was gradually phased up from $2,250 to $10,000 over several years. We count this as a single structural change.

[27] Rute Pinho, “Connecticut Income Tax Rates and Brackets Since 1991,” 3-4.

[28] Office of Fiscal Analysis, Connecticut General Assembly, “The State Budget for the 1990-1991 Fiscal Year,” July 1990, xxix, https://cga.ct.gov/ofa/Documents/year/BB/1991BB-19900701_FY%2091%20Connecticut%20State%20Budget.pdf.

[29] Office of Fiscal Analysis, Connecticut General Assembly, “SB-543: An Act Concerning Revisions to the State Budget for Fiscal Year 2019 and Deficiency Appropriations for Fiscal Year 2018,” 2018, https://cga.ct.gov/2018/FN/2018SB-00543-R00-FN.htm.

[30] Connecticut Department of Revenue Services, “Special Notice – Sales and Use Tax,” TSSN-20, 1989, http://ct.gov/drs/cwp/view.asp?a=1475&q=268944.

[31] Office of Fiscal Analysis, Connecticut General Assembly, “Connecticut Tax ExpenditureTax expenditures are departures from a “normal” tax code that lower the tax burden of individuals or businesses through an exemption, deduction, credit, or preferential rate. However, defining which tax expenditures grant special benefits to certain groups of people or types of economic activity is not always straightforward. Report,” Feb. 13, 2018, https://cga.ct.gov/ofa/Documents/year/TER/2018TER-20180201_Tax%20Expenditure%20Report%20FY%2018.pdf.

[32] Author’s calculations based on U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis Personal Consumer Expenditures data.

[33] South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc., 585 U.S. ___, slip op. (2018).

[34] United States Government Accountability Office, “Sales Taxes: States Could Gain Revenue from Expanded Authority, But Businesses Are Likely to Experience Compliance Costs,” November 2017, 48, https://gao.gov/assets/690/688437.pdf.

[35] Connecticut Commission on Fiscal Stability and Economic Growth, “Final Report,” 44.

[36] Lawrence C. Walters, “The Business Personal Property Tax in Connecticut,” Draft Paper, Nov. 6, 2015, 3, https://cga.ct.gov/fin/tfs%5C20140929_State%20Tax%20Panel%5C20151117/Business%20Tangible%20Property%20Tax%20Walters.pdf.

[37] Joyce Errecart, Ed Gerrish, and Scott Drenkard, “States Moving Away From Taxes on Tangible Personal Property,” Oct. 4, 2012, https://taxfoundation.org/states-moving-away-taxes-tangible-personal-property/.

[38] Id.

[39] Council on State Taxation, “Total State and Local Business Taxes: State-by-State Estimates for Fiscal Year 2016,” August 2017, 22, https://ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/ey-total-state-and-local-business-taxes-2016/$File/ey-total-state-and-local-business-taxes-2016.pdf.

[40] Id., 10; and Lawrence C. Walters, “The Business Personal Property Tax in Connecticut,” 1.

[41] Lawrence C. Walters, “The Business Personal Property Tax in Connecticut,” 23.

[42] Id., 17.

[43] Joyce Errecart, Ed Gerrish, and Scott Drenkard, “States Moving Away From Taxes on Tangible Personal Property.”

[44] Six states impose inheritance taxes; one of them (Maryland) has an estate tax as well. New Jersey had both an inheritance and an estate tax until this year, but now only imposes an inheritance taxAn inheritance tax is levied upon the value of inherited assets received by a beneficiary after a decedent’s death. Not to be confused with estate taxes, which are paid by the decedent’s estate based on the size of the total estate before assets are distributed, inheritance taxes are paid by the recipient or heir based on the value of the bequest received. .

[45] Jeffrey A. Cooper, “Interstate Competition and State Death Taxes: A Modern Crisis in Historical Perspective,” Pepperdine Law Review 33:4 (May 15, 2006), 840.

[46] Stan McMillen et al., “Connecticut’s Spending Cap: Its History and an Alternative Spending Growth Rule,” Connecticut Center for Economic Analysis, September 2005, 2, https://webshare.business.uconn.edu/ccea/studies/Connecticut’s-Spending-Cap-History-Alternative-Spending-Growth-Rule.pdf.

[47] Office of the Attorney General of Connecticut, “Formal Opinion 2015-05,” Nov. 17, 2015, https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/AG/Opinions/2015/2015-05_fasano_spending_caps-pdf.pdf.

[48] Id., 7-9.

[49] Keith M. Phaneuf and Mark Pazniokas, “AG Declares Constitutional Spending Cap Unenforceable,” The Connecticut Mirror, Nov. 17, 2015, https://ctmirror.org/2015/11/17/ag-declares-constitutional-spending-cap-invalid/.

Share this article