Executive Summary

The TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. Foundation’s State Business Tax Climate Index enables business leaders, government policymakers, and taxpayers to gauge how their states’ tax systems compare. While there are many ways to show how much is collected in taxes by state governments, the Index is designed to show how well states structure their tax systems and provides a road map for improvement.

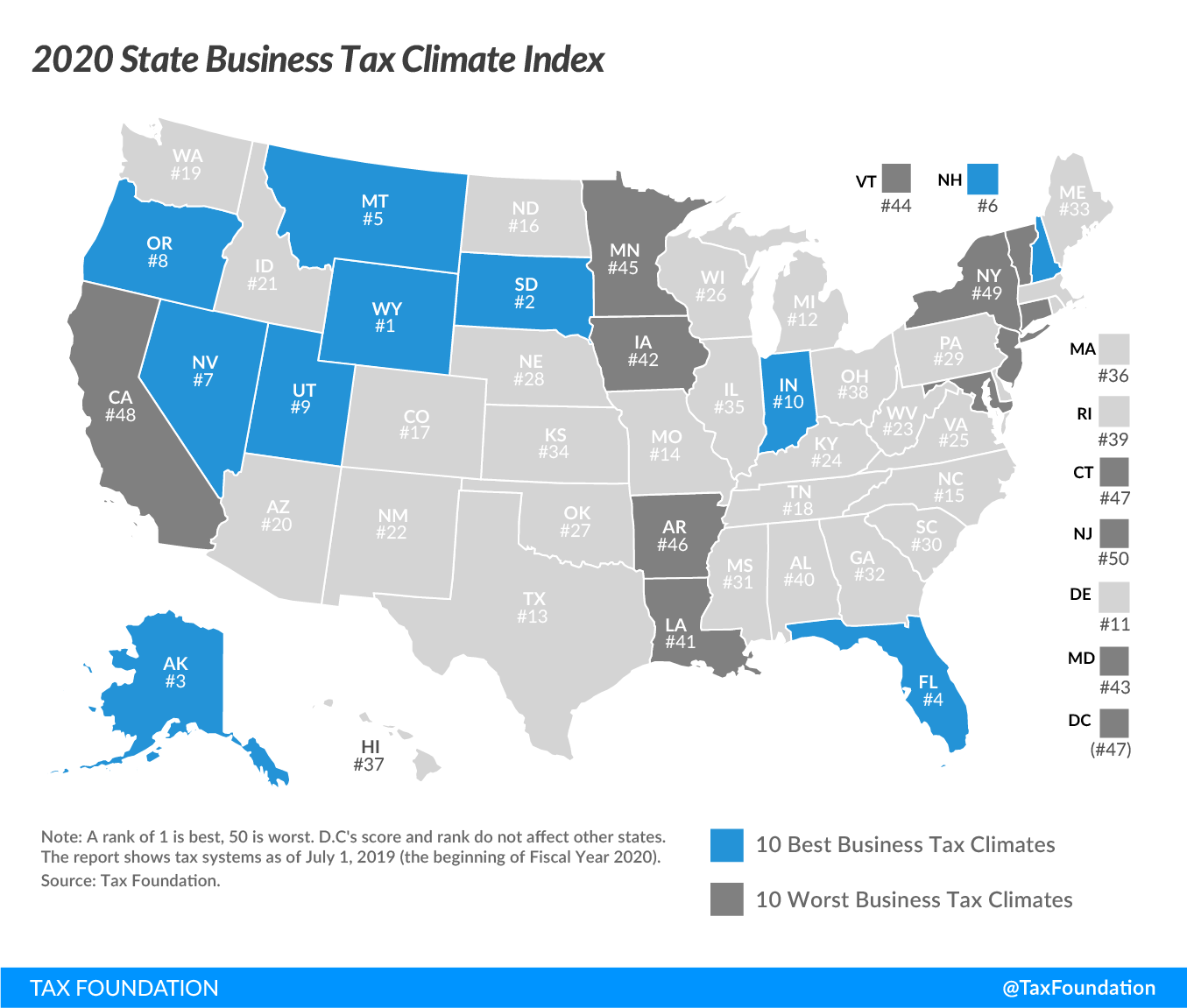

The 10 best states in this year’s Index are:

The absence of a major tax is a common factor among many of the top 10 states. Property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services. es and unemployment insurance taxes are levied in every state, but there are several states that do without one or more of the major taxes: the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. , the individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. , or the sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. . Wyoming, Nevada, and South Dakota have no corporate or individual income tax (though Nevada imposes gross receipts taxA gross receipts tax, also known as a turnover tax, is applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like costs of goods sold and compensation. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and apply to business-to-business transactions in addition to final consumer purchases, leading to tax pyramiding. es); Alaska has no individual income or state-level sales tax; Florida has no individual income tax; and New Hampshire, Montana, and Oregon have no sales tax.

This does not mean, however, that a state cannot rank in the top 10 while still levying all the major taxes. Indiana and Utah, for example, levy all of the major tax types, but do so with low rates on broad bases.

The 10 lowest-ranked, or worst, states in this year’s Index are:

The states in the bottom 10 tend to have a number of afflictions in common: complex, nonneutral taxes with comparatively high rates. New Jersey, for example, is hampered by some of the highest property tax burdens in the country, has the second highest-rate corporate income tax in the country and a particularly aggressive treatment of international income, levies an inheritance taxAn inheritance tax is levied upon an individual’s estate at death or upon the assets transferred from the decedent’s estate to their heirs. Unlike estate taxes, inheritance tax exemptions apply to the size of the gift rather than the size of the estate. , and maintains some of the nation’s worst-structured individual income taxes.

|

Note: A rank of 1 is best, 50 is worst. Rankings do not average to the total. States without a tax rank equally as 1. DC’s score and rank do not affect other states. The report shows tax systems as of July 1, 2019 (the beginning of Fiscal Year 2020). Source: Tax Foundation. |

||||||

| State | Overall Rank | Corporate Tax Rank | Individual Income Tax Rank | Sales Tax Rank | Property Tax Rank | Unemployment Insurance Tax Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 40 | 23 | 30 | 50 | 15 | 18 |

| Alaska | 3 | 26 | 1 | 5 | 25 | 46 |

| Arizona | 20 | 22 | 17 | 40 | 8 | 6 |

| Arkansas | 46 | 34 | 40 | 46 | 29 | 23 |

| California | 48 | 28 | 49 | 45 | 16 | 22 |

| Colorado | 17 | 7 | 14 | 37 | 14 | 43 |

| Connecticut | 47 | 27 | 43 | 26 | 50 | 21 |

| Delaware | 11 | 50 | 41 | 2 | 6 | 3 |

| Florida | 4 | 9 | 1 | 23 | 13 | 2 |

| Georgia | 32 | 6 | 36 | 29 | 28 | 39 |

| Hawaii | 37 | 16 | 47 | 30 | 11 | 28 |

| Idaho | 21 | 29 | 26 | 12 | 4 | 48 |

| Illinois | 35 | 36 | 13 | 33 | 40 | 40 |

| Indiana | 10 | 11 | 15 | 20 | 2 | 25 |

| Iowa | 42 | 48 | 42 | 15 | 35 | 35 |

| Kansas | 34 | 35 | 23 | 38 | 20 | 14 |

| Kentucky | 24 | 17 | 18 | 14 | 36 | 49 |

| Louisiana | 41 | 37 | 32 | 48 | 33 | 4 |

| Maine | 33 | 38 | 22 | 8 | 43 | 32 |

| Maryland | 43 | 32 | 45 | 19 | 42 | 33 |

| Massachusetts | 36 | 39 | 11 | 13 | 48 | 50 |

| Michigan | 12 | 18 | 12 | 9 | 24 | 17 |

| Minnesota | 45 | 44 | 46 | 28 | 26 | 34 |

| Mississippi | 31 | 10 | 27 | 34 | 37 | 5 |

| Missouri | 14 | 5 | 24 | 24 | 7 | 9 |

| Montana | 5 | 21 | 25 | 3 | 12 | 20 |

| Nebraska | 28 | 31 | 21 | 10 | 41 | 11 |

| Nevada | 7 | 25 | 5 | 44 | 10 | 47 |

| New Hampshire | 6 | 43 | 9 | 1 | 44 | 45 |

| New Jersey | 50 | 49 | 50 | 42 | 47 | 30 |

| New Mexico | 22 | 20 | 31 | 41 | 1 | 8 |

| New York | 49 | 13 | 48 | 43 | 46 | 38 |

| North Carolina | 15 | 3 | 16 | 21 | 34 | 10 |

| North Dakota | 16 | 19 | 20 | 27 | 3 | 13 |

| Ohio | 38 | 42 | 44 | 32 | 9 | 7 |

| Oklahoma | 27 | 8 | 33 | 39 | 19 | 1 |

| Oregon | 8 | 33 | 38 | 4 | 18 | 36 |

| Pennsylvania | 29 | 46 | 19 | 17 | 21 | 42 |

| Rhode Island | 39 | 40 | 29 | 25 | 45 | 31 |

| South Carolina | 30 | 4 | 34 | 31 | 30 | 26 |

| South Dakota | 2 | 1 | 1 | 35 | 22 | 44 |

| Tennessee | 18 | 24 | 8 | 47 | 31 | 24 |

| Texas | 13 | 47 | 6 | 36 | 38 | 12 |

| Utah | 9 | 12 | 10 | 22 | 5 | 15 |

| Vermont | 44 | 45 | 39 | 16 | 49 | 16 |

| Virginia | 25 | 14 | 35 | 11 | 32 | 41 |

| Washington | 19 | 41 | 6 | 49 | 27 | 19 |

| West Virginia | 23 | 15 | 28 | 18 | 17 | 29 |

| Wisconsin | 26 | 30 | 37 | 7 | 23 | 37 |

| Wyoming | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 39 | 27 |

| District of Columbia | 47 | 15 | 45 | 36 | 49 | 35 |

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeNotable Ranking Changes in this Year’s Index

Arizona

As part of the state’s belated conformity with the new federal tax law, Arizona trimmed its income tax rates, bringing the top rate down from 4.54 to 4.5 percent and consolidating the two lowest brackets.[1] The reduction was too modest to improve Arizona’s overall rank, but drove a two-place improvement in Arizona’s rank on the individual income tax component of the Index, from 19th to 17th.

Georgia

In 2018, in response to base broadeningBase broadening is the expansion of the amount of economic activity subject to tax, usually by eliminating exemptions, exclusions, deductions, credits, and other preferences. Narrow tax bases are non-neutral, favoring one product or industry over another, and can undermine revenue stability. from federal tax reform, Georgia lawmakers adopted a tax cut package which reduces individual and corporate income tax rates from 6.0 to 5.5 percent in two phases, beginning with reductions to 5.75 percent for tax year 2019. Rates are scheduled to revert after 2025, when the federal changes are currently expected to sunset.[2] These rate reductions helped Georgia improve four places on this year’s Index, from 36th to 32nd overall, while going from 8th to 6th on the corporate tax component, where the lower rate complements an already competitive overall tax structure, and from 38th to 36th on the individual income tax component. The state’s corporate tax component score, in both the 2019 and 2020 Index, also benefits from the state’s decision to decouple from GILTI, which was newly introduced as an Index variable this year.

Indiana

The only state to make midyear rate adjustments, Indiana made another scheduled adjustment to its corporate income tax rate on July 1, 2019, the Index’s snapshot date, bringing the rate from 5.75 to 5.5 percent.[3] This reduction was not enough to improve the state’s already highly competitive overall rank, but, along with modestly negative corporate tax changes in similarly ranked states, helped Indiana improve from 18th to 11th on the corporate tax component of the Index.

Iowa

This year marked the first phase of Iowa’s tax reform package, which will ultimately convert the state’s nine-bracket individual income tax, with a top rate of 8.98 percent, to a four-bracket tax with a top rate of 6.5 percent, while increasing Section 179 small business expensing and eliminating the state’s unusual policy of federal deductibility. Modest sales tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. broadening also features in the package, and the corporate rate will decline from 12 to 9.8 percent, though that rate reduction remains several years out. This year, the top marginal individual income tax rate was cut from 8.98 to 8.53 percent and the Section 179 expensing allowance rose from $70,000 to $100,000, yielding an improvement of one place on the Index overall, from 43rd to 42nd. Further improvements can be anticipated once additional reforms phase in.

Kansas

Through a combination of legislative inaction, vetoes, and agency actions, Kansas has taken an aggressive stance on the taxation of international income and is moving forward with sales tax collection requirements for remote sellers without adopting a safe harbor for small sellers. Because many of its peers have taken a less aggressive approach to the taxation of international income, and no other state has adopted a remote sales tax regime without a de minimis threshold, Kansas dropped seven places on the Index overall, from 27th to 34th.

Massachusetts

Massachusetts adopted a payroll taxA payroll tax is a tax paid on the wages and salaries of employees to finance social insurance programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance. Payroll taxes are social insurance taxes that comprise 24.8 percent of combined federal, state, and local government revenue, the second largest source of that combined tax revenue. of 0.63 percent in addition to its individual income tax, which phased down from a 5.1 to a 5.05 percent flat rate. (We consider the 0.63 percent tax an increase in the rate on wage income for purposes of the Index.) The state also increased unemployment insurance rates, reestablished a sales tax holidayA sales tax holiday is a period of time when selected goods are exempted from state (and sometimes local) sales taxes. Such holidays have become an annual event in many states, with exemptions for such targeted products as back-to-school supplies, clothing, computers, hurricane preparedness supplies, and more. , and made other changes which resulted in a decline from 33rd to 36th overall on the Index.

Missouri

A reduction in the state’s top individual income tax rate, from 5.9 to 5.4 percent, along with the consolidation of an income tax bracketA tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. , improved the state two places on the individual income tax component, from 26th to 24th. Reforms adopted in 2018 will see the individual income tax rate continue to phase down in future years, with a target of 5.1 percent.[4] Next year, the state will no longer give companies the option of choosing the apportionmentApportionment is the determination of the percentage of a business’ profits subject to a given jurisdiction’s corporate income or other business taxes. U.S. states apportion business profits based on some combination of the percentage of company property, payroll, and sales located within their borders. formula most favorable to them, but this consolidation into a single apportionment formula will pay down a significant corporate income tax rate reduction, from 6.25 to 4 percent, which will further improve the state’s rank.

New Hampshire

The Granite State climbed from 7th to 6th overall, and from 46th to 43rd on the corporate tax component, by trimming the rates of both its Business Profits Tax, a corporate income tax, and its Business Enterprise Tax, a value-added tax. The Business Profits Tax rate is now 7.7 percent, down from 7.9 percent in 2018 and 8.2 percent before that, while the Business Enterprise Tax now stands at 0.6 percent, having phased down from 0.675 percent last year and 0.72 percent before that.[5]

North Carolina

North Carolina’s individual income tax rate decreased from 5.499 to 5.25 percent, while the corporate income tax rate—already the nation’s lowest—was cut from 3 to 2.5 percent, completing the latest in several rounds of tax reforms and rate reductions in North Carolina in recent years.[6] These improvements, however, did not help the state on the Index overall, because they failed to leapfrog any states on the corporate or individual income tax components, while changes to the state’s unemployment insurance tax regime, along with improvements in other highly competitive states, slid the state three places from 12th to 15th.

Utah

Utah slid from 8th to 9th on the Index as the state increased its sales tax by 0.15 percentage points in support of Medicaid expansion,[7] but barring new developments, the state is likely to reclaim its old position next year, when Oregon (now in 8th place) implements its newly-adopted gross receipts tax.

Wisconsin

The culmination of a tax package adopted in 2017, Wisconsin repealed its alternative minimum tax for individual filers effective January 2019 and improved two places on the individual component of the Index. The state also benefited greatly from other states shifting around it, increasing its overall rank dramatically, to 26th from 34th.

District of Columbia

The federal district slid eight places on the sales tax component of the Index when it raised its sales tax rate from 5.75 to 6 percent, reversing a reduction made in 2013.[8] This significant movement is reflective of how many states with similar sales tax structures are tightly bunched around a 6 percent rate. The District of Columbia remains 47th overall, although D.C. is given “phantom” ranks in the Index, meaning that its ranks are given by way of example and do not affect the rankings of the 50 states.

Recent and Proposed Changes Not Reflected in the 2020 State Business Tax Climate Index

Arkansas

In 2019, Arkansas adopted a package of individual and corporate income tax reforms which will ultimately see the top individual income tax rate decline from 6.9 to 5.9 percent while consolidating six brackets into three, along with a phasedown of the corporate income tax rate from 6.5 to 5.9 percent, and extension of the net operating loss carryforwardA Net Operating Loss (NOL) Carryforward allows businesses suffering losses in one year to deduct them from future years’ profits. Businesses thus are taxed on average profitability, making the tax code more neutral. In the U.S., a net operating loss can be carried forward indefinitely but are limited to 80 percent of taxable income. period from five to 10 years, among other changes.[9] The state also raised the gas taxA gas tax is commonly used to describe the variety of taxes levied on gasoline at both the federal and state levels, to provide funds for highway repair and maintenance, as well as for other government infrastructure projects. These taxes are levied in a few ways, including per-gallon excise taxes, excise taxes imposed on wholesalers, and general sales taxes that apply to the purchase of gasoline. . Because most of these changes are scheduled for later years, Arkansas’ overall rank did not change this year, but they will be reflected in subsequent versions of the Index.

Mississippi

Mississippi has begun phasing out its capital stock tax, following an exemption added in 2018 with the first rate reduction, from 2.5 to 2.25 mills, in 2019. The tax will slowly phase out through 2028, but the modest rate reduction is not enough to move the needle on Index ranks.[10]

Tennessee

In 2016, Tennessee began phasing out its Hall Tax, a tax on interest and dividend income, though the state does not tax wage income.[11] The Index includes this tax at a calculated rate to reflect its unusually narrow base. Initial reductions are too small to change any component rankings, but Tennessee’s rank will improve once the tax is fully phased out in 2021.

Oregon

In May 2019, the Oregon legislature adopted a modified gross receipts tax, imposed at $250 plus a rate of 0.57 percent on Oregon gross receipts above $1 million. Taxpayers will be permitted to subtract 35 percent of the greater of compensation or the cost of goods sold, putting it somewhere between Ohio’s commercial activity tax and Texas’ franchise (“margin”) tax.[12] When the new tax is implemented, Oregon will become one of only two states, with Delaware, to impose both a corporate income tax and a gross receipts tax. However, the new tax is not reflected in the current edition of the Index, as it does not go into effect until January 1, 2020.

|

Note: A rank of 1 is best, 50 is worst. All scores are for fiscal years. DC’s score and rank do not affect other states. Source: Tax Foundation. |

|||||||||||

| 2020 | 2019 | 2019-2020 Change | Prior Year Ranks | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 |

| Alabama | 40 | 4.53 | 40 | 4.57 | 0 | 0.04 | 39 | 38 | 40 | 40 | 39 |

| Alaska | 3 | 7.22 | 3 | 7.27 | 0 | 0.05 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Arizona | 20 | 5.26 | 20 | 5.22 | 0 | -0.04 | 19 | 18 | 20 | 22 | 19 |

| Arkansas | 46 | 4.34 | 46 | 4.29 | 0 | -0.05 | 42 | 42 | 45 | 41 | 41 |

| California | 48 | 4.02 | 49 | 3.97 | -1 | -0.05 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 | 48 |

| Colorado | 17 | 5.30 | 16 | 5.34 | 1 | 0.04 | 17 | 19 | 18 | 20 | 20 |

| Connecticut | 47 | 4.23 | 47 | 4.12 | 0 | -0.11 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 47 |

| Delaware | 11 | 5.57 | 11 | 5.57 | 0 | 0.00 | 20 | 20 | 14 | 13 | 18 |

| Florida | 4 | 6.80 | 4 | 6.85 | 0 | 0.05 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Georgia | 32 | 4.91 | 36 | 4.84 | -4 | -0.06 | 34 | 34 | 34 | 32 | 30 |

| Hawaii | 37 | 4.68 | 37 | 4.71 | 0 | 0.04 | 26 | 26 | 32 | 31 | 29 |

| Idaho | 21 | 5.23 | 21 | 5.22 | 0 | -0.01 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 18 | 15 |

| Illinois | 35 | 4.87 | 35 | 4.85 | 0 | -0.02 | 28 | 24 | 27 | 36 | 31 |

| Indiana | 10 | 5.59 | 10 | 5.70 | 0 | 0.10 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Iowa | 42 | 4.38 | 43 | 4.40 | -1 | 0.02 | 44 | 43 | 43 | 42 | 42 |

| Kansas | 34 | 4.88 | 27 | 4.99 | 7 | 0.11 | 27 | 28 | 26 | 26 | 25 |

| Kentucky | 24 | 5.10 | 24 | 5.08 | 0 | -0.02 | 37 | 37 | 36 | 38 | 35 |

| Louisiana | 41 | 4.41 | 41 | 4.44 | 0 | 0.02 | 46 | 46 | 38 | 37 | 37 |

| Maine | 33 | 4.90 | 31 | 4.88 | 2 | -0.02 | 36 | 35 | 37 | 35 | 32 |

| Maryland | 43 | 4.37 | 42 | 4.43 | 1 | 0.06 | 40 | 40 | 39 | 39 | 40 |

| Massachusetts | 36 | 4.81 | 33 | 4.88 | 3 | 0.07 | 29 | 31 | 29 | 30 | 28 |

| Michigan | 12 | 5.54 | 17 | 5.34 | -5 | -0.20 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 11 |

| Minnesota | 45 | 4.35 | 44 | 4.37 | 1 | 0.02 | 43 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 44 |

| Mississippi | 31 | 4.96 | 30 | 4.94 | 1 | -0.01 | 32 | 32 | 30 | 28 | 26 |

| Missouri | 14 | 5.43 | 14 | 5.39 | 0 | -0.05 | 15 | 15 | 19 | 15 | 12 |

| Montana | 5 | 6.16 | 5 | 6.22 | 0 | 0.06 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Nebraska | 28 | 5.01 | 26 | 5.06 | 2 | 0.06 | 31 | 30 | 28 | 27 | 36 |

| Nevada | 7 | 5.88 | 6 | 5.93 | 1 | 0.05 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| New Hampshire | 6 | 6.01 | 7 | 5.91 | -1 | -0.10 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| New Jersey | 50 | 3.24 | 50 | 3.24 | 0 | 0.01 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | 49 |

| New Mexico | 22 | 5.13 | 23 | 5.10 | -1 | -0.03 | 24 | 25 | 24 | 25 | 24 |

| New York | 49 | 4.01 | 48 | 4.00 | 1 | 0.00 | 49 | 49 | 49 | 49 | 50 |

| North Carolina | 15 | 5.43 | 12 | 5.47 | 3 | 0.04 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 34 |

| North Dakota | 16 | 5.36 | 15 | 5.39 | 1 | 0.03 | 18 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 |

| Ohio | 38 | 4.67 | 38 | 4.68 | 0 | 0.01 | 41 | 39 | 42 | 43 | 43 |

| Oklahoma | 27 | 5.01 | 28 | 4.95 | -1 | -0.06 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 21 | 22 |

| Oregon | 8 | 5.74 | 9 | 5.73 | -1 | -0.01 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Pennsylvania | 29 | 4.97 | 32 | 4.88 | -3 | -0.09 | 30 | 29 | 33 | 33 | 33 |

| Rhode Island | 39 | 4.57 | 39 | 4.63 | 0 | 0.06 | 38 | 41 | 41 | 45 | 45 |

| South Carolina | 30 | 4.96 | 29 | 4.95 | 1 | -0.01 | 33 | 33 | 31 | 29 | 27 |

| South Dakota | 2 | 7.34 | 2 | 7.28 | 0 | -0.06 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Tennessee | 18 | 5.29 | 18 | 5.29 | 0 | 0.00 | 14 | 14 | 16 | 16 | 13 |

| Texas | 13 | 5.46 | 13 | 5.42 | 0 | -0.04 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 14 | 14 |

| Utah | 9 | 5.70 | 8 | 5.84 | 1 | 0.14 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Vermont | 44 | 4.35 | 45 | 4.36 | -1 | 0.02 | 45 | 45 | 46 | 46 | 46 |

| Virginia | 25 | 5.02 | 25 | 5.07 | 0 | 0.05 | 25 | 27 | 25 | 24 | 21 |

| Washington | 19 | 5.28 | 19 | 5.28 | 0 | 0.00 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 19 | 16 |

| West Virginia | 23 | 5.12 | 22 | 5.11 | 1 | -0.01 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 23 | 23 |

| Wisconsin | 26 | 5.01 | 34 | 4.86 | -8 | -0.16 | 35 | 36 | 35 | 34 | 38 |

| Wyoming | 1 | 7.62 | 1 | 7.52 | 0 | -0.09 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| District of Columbia | 47 | 4.24 | 47 | 4.25 | 0 | 0.01 | 48 | 48 | 45 | 47 | 47 |

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeIntroduction

Taxation is inevitable, but the specifics of a state’s tax structure matter greatly. The measure of total taxes paid is relevant, but other elements of a state tax system can also enhance or harm the competitiveness of a state’s business environment. The State Business Tax Climate Index distills many complex considerations to an easy-to-understand ranking.

The modern market is characterized by mobile capital and labor, with all types of businesses, small and large, tending to locate where they have the greatest competitive advantage. The evidence shows that states with the best tax systems will be the most competitive at attracting new businesses and most effective at generating economic and employment growth. It is true that taxes are but one factor in business decision-making. Other concerns also matter–such as access to raw materials or infrastructure or a skilled labor pool–but a simple, sensible tax system can positively impact business operations with regard to these resources. Furthermore, unlike changes to a state’s health-care, transportation, or education systems, which can take decades to implement, changes to the tax code can quickly improve a state’s business climate.

It is important to remember that even in our global economy, states’ stiffest competition often comes from other states. The Department of Labor reports that most mass job relocations are from one U.S. state to another rather than to a foreign location.[13] Certainly, job creation is rapid overseas, as previously underdeveloped nations enter the world economy, though in the aftermath of federal tax reform, U.S. businesses no longer face the third-highest corporate tax rate in the world, but rather one in line with averages for industrialized nations.[14] State lawmakers are right to be concerned about how their states rank in the global competition for jobs and capital, but they need to be more concerned with companies moving from Detroit, Michigan, to Dayton, Ohio, than from Detroit to New Delhi, India. This means that state lawmakers must be aware of how their states’ business climates match up against their immediate neighbors and to other regional competitor states.

Anecdotes about the impact of state tax systems on business investment are plentiful. In Illinois early last decade, hundreds of millions of dollars of capital investments were delayed when then-Governor Rod Blagojevich (D) proposed a hefty gross receipts tax.[15] Only when the legislature resoundingly defeated the bill did the investment resume. In 2005, California-based Intel decided to build a multibillion-dollar chip-making facility in Arizona due to its favorable corporate income tax system.[16] In 2010, Northrup Grumman chose to move its headquarters to Virginia over Maryland, citing the better business tax climate.[17] In 2015, General Electric and Aetna threatened to decamp from Connecticut if the governor signed a budget that would increase corporate tax burdens, and General Electric actually did so.[18] Anecdotes such as these reinforce what we know from economic theory: taxes matter to businesses, and those places with the most competitive tax systems will reap the benefits of business-friendly tax climates.

Tax competition is an unpleasant reality for state revenue and budget officials, but it is an effective restraint on state and local taxes. When a state imposes higher taxes than a neighboring state, businesses will cross the border to some extent. Therefore, states with more competitive tax systems score well in the Index, because they are best suited to generate economic growth.

State lawmakers are mindful of their states’ business tax climates, but they are sometimes tempted to lure business with lucrative tax incentives and subsidies instead of broad-based tax reform. This can be a dangerous proposition, as the example of Dell Computers and North Carolina illustrates. North Carolina agreed to $240 million worth of incentives to lure Dell to the state. Many of the incentives came in the form of tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. s from the state and local governments. Unfortunately, Dell announced in 2009 that it would be closing the plant after only four years of operations.[19] A 2007 USA TODAY article chronicled similar problems other states have had with companies that receive generous tax incentives.[20]

Lawmakers make these deals under the banner of job creation and economic development, but the truth is that if a state needs to offer such packages, it is most likely covering for an undesirable business tax climate. A far more effective approach is the systematic improvement of the state’s business tax climate for the long term to improve the state’s competitiveness. When assessing which changes to make, lawmakers need to remember two rules:

- Taxes matter to business. Business taxes affect business decisions, job creation and retention, plant location, competitiveness, the transparency of the tax system, and the long-term health of a state’s economy. Most importantly, taxes diminish profits. If taxes take a larger portion of profits, that cost is passed along to either consumers (through higher prices), employees (through lower wages or fewer jobs), or shareholders (through lower dividends or share value), or some combination of the above. Thus, a state with lower tax costs will be more attractive to business investment and more likely to experience economic growth.

- States do not enact tax changes (increases or cuts) in a vacuum. Every tax law will in some way change a state’s competitive position relative to its immediate neighbors, its region, and even globally. Ultimately, it will affect the state’s national standing as a place to live and to do business. Entrepreneurial states can take advantage of the tax increases of their neighbors to lure businesses out of high-tax states.

To some extent, tax-induced economic distortions are a fact of life, but policymakers should strive to maximize the occasions when businesses and individuals are guided by business principles and minimize those cases where economic decisions are influenced, micromanaged, or even dictated by a tax system. The more riddled a tax system is with politically motivated preferences, the less likely it is that business decisions will be made in response to market forces. The Index rewards those states that minimize tax-induced economic distortions.

Ranking the competitiveness of 50 very different tax systems presents many challenges, especially when a state dispenses with a major tax entirely. Should Indiana’s tax system, which includes three relatively neutral taxes on sales, individual income, and corporate income, be considered more or less competitive than Alaska’s tax system, which includes a particularly burdensome corporate income tax but no statewide tax on individual income or sales?

The Index deals with such questions by comparing the states on more than 120 variables in the five major areas of taxation (corporate taxes, individual income taxes, sales taxes, unemployment insurance taxes, and property taxes) and then adding the results to yield a final, overall ranking. This approach rewards states on particularly strong aspects of their tax systems (or penalizes them on particularly weak aspects), while measuring the general competitiveness of their overall tax systems. The result is a score that can be compared to other states’ scores. Ultimately, both Alaska and Indiana score well.

Note: This map is part of a series in which we will examine each of the five major components of our 2020 State Business Tax Climate Index.

- How Does Your State Compare on our 2020 State Business Tax Climate Index?

- How Does Your State Compare on Corporate Taxes?

- How Does Your State Compare on Individual Income Taxes?

- How Does Your State Compare on Sales Taxes?

- How Does Your State Compare on Property Taxes?

- How Does Your State Compare on Unemployment Insurance Taxes?

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeNotes

[1] Jared Walczak, “Arizona Delivers Rate Cuts and Tax Conformity,” Tax Foundation, June 6, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/arizona-income-tax-cuts-tax-conformity/.

[2] Jared Walczak, “Two States Cut Taxes Due to Federal Tax Reform,” Tax Foundation, March 19, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/two-states-cut-taxes-due-federal-tax-reform.

[3] Katherine Loughead, “State Tax Changes as of July 1, 2019,” Tax Foundation, July 11, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/state-tax-changes-effective-july-1-2019/.

[4] Jared Walczak, “Missouri Governor Set to Sign Income Tax Cuts,” Tax Foundation, July 11, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/missouri-governor-set-sign-income-tax-cuts/.

[5] Jared Walczak, “Tax Changes Taking Effect January 1, 2019,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 27, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/state-tax-changes-january-2019/.

[6] Nicole Kaeding, “North Carolina Continues Its Successful Tax Reforms,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 27, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/north-carolina-continues-tax-reforms/.

[7] Jared Walczak, “Modernizing Utah’s Sales Tax: A Guide for Policymakers,” Tax Foundation, June 4, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/modernizing-utah-sales-tax/.

[8] Joseph Bishop-Henchman, “D.C. Proposes Sales Tax Increase, Other Tax Changes,” Tax Foundation, May 16, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/d-c-proposes-sales-tax-increase-tax-changes/.

[9] Nicole Kaeding and Jeremy Horpedahl, “Recapping the 2019 Arkansas Tax Reform,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 11, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/recapping-2019-arkansas-tax-reform/.

[10] Walczak, “Tax Changes Taking Effect January 1, 2019.”

[11] Mike Pare, “Tennessee On Its Way to Becoming a Bona Fide No-Income Tax State in 2021,” Chattanooga Times Free Press, Feb. 1, 2019, https://www.timesfreepress.com/news/edge/story/2019/feb/01/hall-income-tax-ending-2021/487137/.

[12] Corey L. Rosenthal and Jessie Hu, “Oregon’s New Commercial Activity Tax,” The CPA Journal (September 2019), https://www.cpajournal.com/2019/09/18/oregons-new-commercial-activity-tax/.

[13] See U.S. Department of Labor, “Extended Mass Layoffs, First Quarter 2013,” Table 10, May 13, 2013.

[14] Daniel Bunn, “Corporate Income Tax Rates Around the World, 2018,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 27, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/publications/corporate-tax-rates-around-the-world/.

[15] Editorial, “Scale it back, Governor,” Chicago Tribune, March 23, 2007.

[16] Ryan Randazzo, Edythe Jenson, and Mary Jo Pitzl, “Cathy Carter Blog: Chandler getting new $5 billion Intel facility,” AZCentral.com, Mar. 6, 2013.

[17] Dana Hedgpeth and Rosalind Helderman, “Northrop Grumman decides to move headquarters to Northern Virginia,” The Washington Post, April 27, 2010.

[18] Susan Haigh, “Connecticut House Speaker: Tax ‘mistakes’ made in budget,” Associated Press, Nov. 5, 2015.

[19] Austin Mondine, “Dell cuts North-Carolina plant despite $280m sweetener,” TheRegister.co.uk, Oct. 8, 2009.

[20] Dennis Cauchon, “Business Incentives Lose Luster for States,” USA TODAY, Aug. 22, 2007.

Share