Key Findings

- Forty-five states and the District of Columbia collect statewide sales taxes.

- Local sales taxes are collected in 38 states. In some cases, they can rival or even exceed state rates.

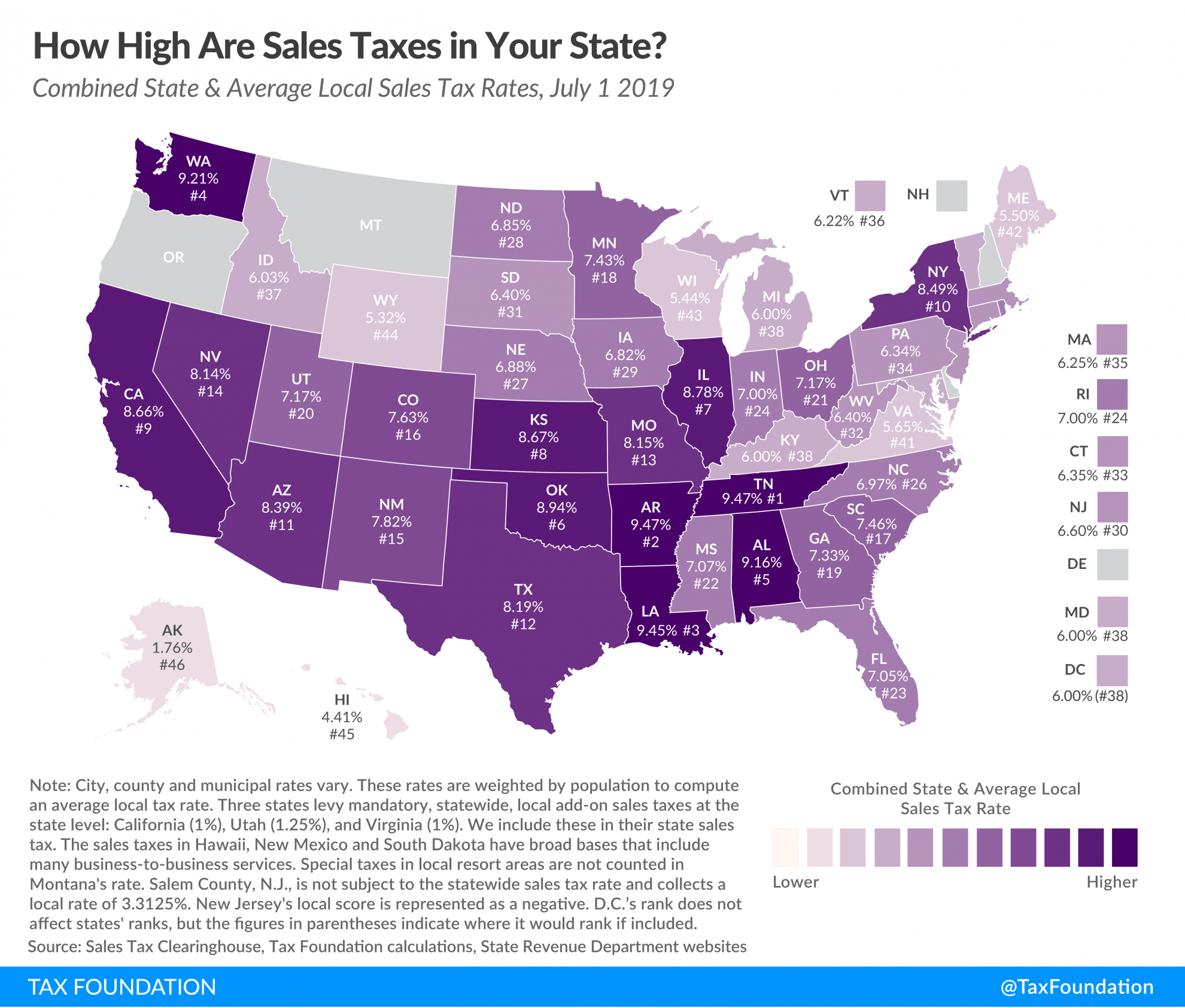

- The five states with the highest average combined state and local sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. rates are Tennessee and Arkansas (9.47 percent), Louisiana (9.45 percent), Washington (9.21 percent), and Alabama (9.16 percent).

- Utah’s statewide rate increased from 5.95 percent to 6.1 percent in April 2019. No other state rates have changed since July 2018, although the District of Columbia’s rate increased to 6 percent in October 2018.

- Sales taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. rates differ by state, but sales tax bases also impact how much revenue is collected from a tax and how the tax affects the economy.

- Sales tax rate differentials can induce consumers to shop across borders or buy products online.

Introduction

Retail sales taxes are one of the more transparent ways to collect tax revenue. While graduated income tax rates and brackets are complex and confusing to many taxpayers, sales taxes are easier to understand; consumers can see their tax burden printed directly on their receipts.

In addition to state-level sales taxes, consumers also face local sales taxes in 38 states. These rates can be substantial, so a state with a moderate statewide sales tax rate could actually have a very high combined state and local rate compared to other states. This report provides a population-weighted average of local sales taxes as of July 1, 2019, to give a sense of the average local rate for each state. Table 1 provides a full state-by-state listing of state and local sales tax rates.

Combined Rates

Five states do not have statewide sales taxes: Alaska, Delaware, Montana, New Hampshire, and Oregon. Of these, Alaska allows localities to charge local sales taxes.[1]

The five states with the highest average combined state and local sales tax rates are Tennessee and Arkansas (9.47 percent), Louisiana (9.45 percent), Washington (9.21 percent), and Alabama (9.16 percent). The five states with the lowest average combined rates are Alaska (1.76 percent), Hawaii (4.41 percent), Wyoming (5.32 percent), Wisconsin (5.44 percent), and Maine (5.50 percent).

State Rates

California has the highest state-level sales tax rate, at 7.25 percent.[2] Four states tie for the second-highest statewide rate, at 7 percent: Indiana, Mississippi, Rhode Island, and Tennessee. The lowest non-zero state-level sales tax is in Colorado, which has a rate of 2.9 percent. Five states follow with 4 percent rates: Alabama, Georgia, Hawaii, New York, and Wyoming.[3]

Utah’s statewide rate increased from 5.95 percent to 6.1 percent in April 2019, jumping the ranking 10 places to 20th highest statewide sales tax rates.[4] No other state rates have changed since July 2018, although the District of Columbia’s rate increased to 6 percent in October 2018.[5]

Local Rates

The five states with the highest average local sales tax rates are Alabama (5.16 percent), Louisiana (5.00 percent), Colorado (4.73 percent), New York (4.49 percent), and Oklahoma (4.44 percent).

In addition to its statewide change, Utah also saw small local rate changes. Although average local rates increased from 0.99 percent to 1.068 percent, the relative stability on the local level helped to moderate the statewide shift. Regardless, Utah still jumped in rank from 26th highest to 20th highest state and local rates. This shift is largely due to Washington and Utah Counties, which both adopted a 0.25 percent sales tax for transportation funding.[6] Several localities also imposed a new 1 percent municipal transient room tax.[7]

California’s local rates rose the second most, although the state remains in ninth place in the rankings. The increase can be traced back to Santa Cruz County’s increase from 1.25 percent to 1.75 percent, Sonoma County’s 0.125 percentage point increase, and various increases in many smaller localities.[8]

Arkansas jumped into second place in July due to a number of annexations, where cities were absorbed into neighboring localities with higher sales taxes.[9] Annexations included Centerton, Pea Ridge, and other small cities. The city of Hampton created a new local rate of 0.5 percent.

Local rates in Alaska rose from 1.43 percent to 1.76 percent without changing the state’s ranking; it remains the only state to levy sales taxes at a local but not state level. This change is largely due to a new 5 percent local sales tax in Whittier, although taxes in Elfin Cove, Seldovia, and Skagway also increased by two percentage points each.[10] Rates increased to 6 percent in Sitka and Sitka City and Borough from a previous 5 percent rate.

Any state whose ranking improved did so only in comparison to those who enacted rate increases. In fact, North Carolina and Louisiana improved their standings by one place while actually seeing small local rate increases.

Wyoming saw a small decrease in its average local rates, and it continues to have the sixth lowest combined sales taxes. Johnson County increased its rates to 6 percent, and Park County decreased its rates to 4 percent, resulting in a slight decrease for the state overall.[11]

It must be noted that some cities in New Jersey are in “Urban Enterprise Zones,” where qualifying sellers may collect and remit at half the 6.625 percent statewide sales tax rate (3.3125 percent), a policy designed to help local retailers compete with neighboring Delaware, which forgoes a sales tax. We represent this anomaly as a negative 0.03 percent statewide average local rate (adjusting for population as described in the methodology section below), and the combined rate reflects this subtraction. Despite the slightly favorable impact on the overall rate, this lower rate represents an implicit acknowledgment by New Jersey officials that their 6.625 percent statewide rate is uncompetitive with neighboring Delaware, which has no sales tax.

| (a) City, county and municipal rates vary. These rates are weighted by population to compute an average local tax rate. (b) Three states levy mandatory, statewide, local add-on sales taxes at the state level: California (1%), Utah (1.25%), and Virginia (1%). We include these in their state sales tax. (c) The sales taxes in Hawaii, New Mexico and South Dakota have broad bases that include many business-to-business services. (d) Special taxes in local resort areas are not counted here. (e) Salem County, N.J., is not subject to the statewide sales tax rate and collects a local rate of 3.3125%. New Jersey’s local score is represented as a negative. Sources: Sales Tax Clearinghouse; Tax Foundation calculations; State Revenue Department websites | ||||||

| State | State Tax Rate | Rank | Avg. Local Tax Rate | Combined Rate | Rank | Max Local Tax Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ala. | 4.00% | 40 | 5.16% | 9.16% | 5 | 7.00% |

| Alaska | 0.00% | 46 | 1.76% | 1.76% | 46 | 7.50% |

| Ariz. | 5.60% | 28 | 2.79% | 8.39% | 11 | 5.60% |

| Ark. | 6.50% | 9 | 2.965% | 9.465% | 2 | 5.13% |

| Calif. (b) | 7.25% | 1 | 1.41% | 8.66% | 9 | 2.50% |

| Colo. | 2.90% | 45 | 4.73% | 7.63% | 16 | 8.30% |

| Conn. | 6.35% | 12 | 0.00% | 6.35% | 33 | 0.00% |

| Del. | 0.00% | 46 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 47 | 0.00% |

| Fla. | 6.00% | 17 | 1.05% | 7.05% | 23 | 2.50% |

| Ga. | 4.00% | 40 | 3.33% | 7.33% | 19 | 5.00% |

| Hawaii (c) | 4.00% | 40 | 0.41% | 4.41% | 45 | 0.50% |

| Idaho | 6.00% | 17 | 0.03% | 6.03% | 37 | 3.00% |

| Ill. | 6.25% | 13 | 2.53% | 8.78% | 7 | 4.75% |

| Ind. | 7.00% | 2 | 0.00% | 7.00% | 24 | 0.00% |

| Iowa | 6.00% | 17 | 0.82% | 6.82% | 29 | 1.00% |

| Kans. | 6.50% | 9 | 2.17% | 8.67% | 8 | 4.00% |

| Ky. | 6.00% | 17 | 0.00% | 6.00% | 38 | 0.00% |

| La. | 4.45% | 38 | 5.00% | 9.45% | 3 | 7.00% |

| Maine | 5.50% | 29 | 0.00% | 5.50% | 42 | 0.00% |

| Md. | 6.00% | 17 | 0.00% | 6.00% | 38 | 0.00% |

| Mass. | 6.25% | 13 | 0.00% | 6.25% | 35 | 0.00% |

| Mich. | 6.00% | 17 | 0.00% | 6.00% | 38 | 0.00% |

| Minn. | 6.88% | 6 | 0.56% | 7.43% | 18 | 2.00% |

| Miss. | 7.00% | 2 | 0.07% | 7.07% | 22 | 1.00% |

| Mo. | 4.23% | 39 | 3.93% | 8.15% | 13 | 5.51% |

| Mont. (d) | 0.00% | 46 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 47 | 0.00% |

| Nebr. | 5.50% | 29 | 1.38% | 6.88% | 27 | 2.00% |

| Nev. | 6.85% | 7 | 1.29% | 8.14% | 14 | 1.42% |

| N.H. | 0.00% | 46 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 47 | 0.00% |

| N.J. (e) | 6.63% | 8 | -0.03% | 6.60% | 30 | 3.31% |

| N.M. (c) | 5.13% | 32 | 2.69% | 7.82% | 15 | 4.13% |

| N.Y. | 4.00% | 40 | 4.49% | 8.49% | 10 | 4.88% |

| N.C. | 4.75% | 35 | 2.22% | 6.97% | 26 | 2.75% |

| N.D. | 5.00% | 33 | 1.85% | 6.85% | 28 | 3.50% |

| Ohio | 5.75% | 27 | 1.42% | 7.17% | 21 | 2.25% |

| Okla. | 4.50% | 36 | 4.44% | 8.94% | 6 | 7.00% |

| Ore. | 0.00% | 46 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 47 | 0.00% |

| Pa. | 6.00% | 17 | 0.34% | 6.34% | 34 | 2.00% |

| R.I. | 7.00% | 2 | 0.00% | 7.00% | 24 | 0.00% |

| S.C. | 6.00% | 17 | 1.46% | 7.46% | 17 | 3.00% |

| S.D. (c) | 4.50% | 36 | 1.90% | 6.40% | 31 | 4.50% |

| Tenn. | 7.00% | 2 | 2.469% | 9.469% | 1 | 2.75% |

| Tex. | 6.25% | 13 | 1.94% | 8.19% | 12 | 2.00% |

| Utah (b) | 6.10% | 16 | 1.068% | 7.168% | 20 | 2.95% |

| Vt. | 6.00% | 17 | 0.22% | 6.22% | 36 | 1.00% |

| Va. (b) | 5.30% | 31 | 0.35% | 5.65% | 41 | 0.70% |

| Wash. | 6.50% | 9 | 2.71% | 9.21% | 4 | 4.00% |

| W.Va. | 6.00% | 17 | 0.40% | 6.40% | 32 | 1.00% |

| Wis. | 5.00% | 33 | 0.44% | 5.44% | 43 | 1.75% |

| Wyo. | 4.00% | 40 | 1.32% | 5.32% | 44 | 2.00% |

| D.C. | 6.00% | (17) | 0.00% | 6.00% | (38) | 0.00% |

The Role of Competition in Setting Sales Tax Rates

Avoidance of sales tax is most likely to occur in areas where there is a significant difference between jurisdictions’ rates. Research indicates that consumers can and do leave high-tax areas to make major purchases in low-tax areas, such as from cities to suburbs.[12] For example, evidence suggests that Chicago-area consumers make major purchases in surrounding suburbs or online to avoid Chicago’s 10.25 percent sales tax rate.[13]

At the statewide level, businesses sometimes locate just outside the borders of high sales-tax areas to avoid being subjected to their rates. A stark example of this occurs in New England, where even though I-91 runs up the Vermont side of the Connecticut River, many more retail establishments choose to locate on the New Hampshire side to avoid sales taxes. One study shows that per capita sales in border counties in sales tax-free New Hampshire have tripled since the late 1950s, while per capita sales in border counties in Vermont have remained stagnant.[14] Delaware actually uses its highway welcome sign to remind motorists that Delaware is the “Home of Tax-Free Shopping.”[15]

State and local governments should be cautious about raising rates too high relative to their neighbors because doing so will yield less revenue than expected or, in extreme cases, revenue losses despite the higher tax rate.

Sales Tax Bases: The Other Half of the Equation

This report ranks states based on tax rates and does not account for differences in tax bases (e.g., the structure of sales taxes, defining what is taxable and nontaxable). States can vary greatly in this regard. For instance, most states exempt groceries from the sales tax, others tax groceries at a limited rate, and still others tax groceries at the same rate as all other products.[16] Some states exempt clothing or tax it at a reduced rate.[17]

Tax experts generally recommend that sales taxes apply to all final retail sales of goods and services but not intermediate business-to-business transactions in the production chain. These recommendations would result in a tax system that is not only broad-based but also “right-sized,” applying once and only once to each product the market produces.[18] Despite agreement in theory, the application of most state sales taxes is far from this ideal.[19]

Hawaii has the broadest sales tax in the United States, but it taxes many products multiple times and, by the estimate of Indiana University professor emeritus John Mikesell, ultimately taxes 105.29 percent of the state’s personal income.[20] This base is far wider than the national median, where the sales tax applies to 34.25 percent of personal income.[21]

Methodology

Sales Tax Clearinghouse publishes quarterly sales tax data at the state, county, and city levels by ZIP code. We weight these numbers according to Census 2010 population figures to give a sense of the prevalence of sales tax rates in a particular state.

It is worth noting that population numbers are only published at the ZIP code level every 10 years by the U.S. Census Bureau, and that editions of this calculation published before July 1, 2011, do not utilize ZIP code data and are thus not strictly comparable.

It should also be noted that while the Census Bureau reports population data using a five-digit identifier that looks much like a ZIP code, this is actually what is called a ZIP Code Tabulation Area (ZCTA), which attempts to create a geographical area associated with a given ZIP code. This is done because a surprisingly large number of ZIP codes do not actually have any residents. For example, the National Press Building in Washington, D.C., has its own ZIP code solely for postal reasons.

For our purposes, ZIP codes that do not have a corresponding ZCTA population figure are omitted from calculations. These omissions result in some amount of inexactitude but overall do not have a palpable effect on resultant averages because proximate ZIP code areas which do have ZCTA population numbers capture the tax rate of those jurisdictions.

Conclusion

Sales taxes are just one part of an overall tax structure and should be considered in context. For example, Tennessee has high sales taxes but no wage income tax, whereas Oregon has no sales tax but high income taxes. While many factors influence business location and investment decisions, sales taxes are something within policymakers’ control that can have immediate impacts.

Notes

[1] Special taxes in Montana’s resort areas are not included in our analysis.

[2] This number includes mandatory add-on taxes which are collected by the state but distributed to local governments. Because of this, some sources will describe California’s sales tax as 6.0 percent. A similar situation exists in Utah and Virginia.

[3] The sales taxes in Hawaii and South Dakota have bases that include many services and so are not strictly comparable to other sales taxes.

[4] This rate includes two levies, summing 1.25 percentage points, which are imposed statewide but distributed to localities. “Second Quarter 2019 Changes,” Tax.Utah.gov, April 1, 2019, https://tax.utah.gov/sales/ratechanges.

[5] “District of Columbia Tax Rates Changes Take Effect Monday, October 1,” DC.gov, Sept. 5, 2018, https://otr.cfo.dc.gov/release/district-columbia-tax-rates-changes-take-effect-monday-october-1.

[6] Mori Kessler, “Washington County adopts quarter-percent sales tax for road, transit funding,” St George News, June 18, 2019, https://www.stgeorgeutah.com/news/archive/2019/06/18/mgk-washington-county-adopts-quarter-percent-sales-tax-for-road-transit-funding/; Katie England, “Utah County passes quarter-cent sales tax in split vote; 2019’s $95 million budget approved,” Daily Herald, Dec. 18, 2018, https://www.heraldextra.com/news/local/govt-and-politics/utah-county-passes-quarter-cent-sales-tax-in-split-vote/article_c3429fe4-1fe7-5ee8-8486-8060ee3def4c.html; “Combined Sales and Use Tax Rates,” Tax.Utah.Gov, July 1, 2019, https://tax.utah.gov/salestax/rate/19q3combined.pdf.

[7] “Third Quarter 2019 Changes,” Tax.Utah.gov, July 1, 2019, https://tax.utah.gov/sales/ratechanges.

[8] “Sales Tax Rates,” County of Santa Cruz, April 2019, http://www.co.santa-cruz.ca.us/Departments/TaxCollector/SalesTaxRates.aspx; Katie Dowd, “Sales tax is going up in dozens of California cities,” SFGate.com, Apr. 1, 2019, https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/california-city-sales-tax-2019-rates-increase-13732684.php.

[9] “Recent Changes for Local Taxes,” Arkansas Department of Finance and Administration, https://www.dfa.arkansas.gov/excise-tax/sales-and-use-tax/recent-changes-for-local-taxes/.

[10] “2019 Sales Tax Reporting Form,” WhittierAlaska.gov, Apr. 1, 2019, http://www.whittieralaska.gov/docs/2019-sales-tax-reporting-form.pdf; “Alaska (AK) Sales Tax Rate Changes,” Sale-Tax.com, Apr. 1, 2019, http://www.sale-tax.com/Alaska-rate-changes.

[11] Stephen Dow, “No fooling,” Buffalo Bulletin, Mar. 27, 2019, http://www.buffalobulletin.com/article_d26d451c-509b-11e9-9e77-5354b2ecb5c6.html; Leo Wolfson, “One cent tax to end March 31,” Cody (Wyo.) Enterprise, Dec. 26, 2018, http://www.codyenterprise.com/news/local/article_6275e838-094f-11e9-a60f-4bf147843a5c.html.

[12] Mehmet Serkan Tosun and Mark Skidmore, “Cross-Border Shopping and the Sales Tax: A Reexamination of Food Purchases in West Virginia,” Research Paper 2005-7, Regional Research Institute, West Virginia University, September 2005, http://rri.wvu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Tosunwp2005-7.pdf. See also T. Randolph Beard, Paula A. Gant, and Richard P. Saba, “Border-Crossing Sales, Tax Avoidance, and State Tax Policies: An Application to Alcohol,” Southern Economic Journal 64:1 (July 1997), 293-306.

[13] Susan Chandler, “The sales tax sidestep,” Chicago Tribune, July 20, 2008, http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2008-07-20/business/0807190001_1_sales-tax-tax-avoidance-tax-landscape.

[14] Arthur Woolf, “The Unintended Consequences of Public Policy Choices: The Connecticut River Valley Economy as a Case Study,” Northern Economic Consulting, Inc., November 2010, http://www.documentcloud.org/documents/603373-the-unintended-consequences-of-public-policy.html.

[15] Len Lazarick, “Raise taxes, and they’ll move, constituents tell one delegate,” Marylandreporter.com, Aug. 3, 2011, http://marylandreporter.com/2011/08/03/raise-taxes-and-theyll-move-constituents-tell-one-delegate/.

[16] For a list, see Jared Walczak, Scott Drenkard, and Joseph Bishop-Henchman, 2019 State Business Tax Climate Index, Tax Foundation, Sept. 26, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/publications/state-business-tax-climate-index/.

[17] Liz Malm and Richard Borean, “How Does Your State Sales Tax See That Blue and Black (or White and Gold) Dress?” Tax Foundation, Feb. 27, 2015, http://taxfoundation.org/blog/how-does-your-state-sales-tax-see-blue-and-black-or-white-and-gold-dress.

[18] Justin M. Ross, “A Primer on State and Local Tax Policy: Trade-Offs among Tax Instruments,” Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Feb. 25, 2014, http://mercatus.org/publication/primer-state-and-local-tax-policy-trade-offs-among-tax-instruments.

[19] For a representative list, see Jared Walczak, Scott Drenkard, and Joseph Henchman, 2019 State Business Tax Climate Index.

[20] Janelle Cammenga, Facts and Figures 2019: How Does Your State Compare? Table 22, Tax Foundation, Mar. 19, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/facts-figures-2019/.

[21] Id.

Share this article