Key Findings

- Individual income taxes are a major source of state government revenue, accounting for 37 percent of state tax collections.

- Forty-three states levy individual income taxes. Forty-one taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. wage and salary income, while two states–New Hampshire and Tennessee–exclusively tax dividend and interest income. Seven states levy no income tax at all.

- Of those states taxing wages, nine have single-rate tax structures, with one rate applying to all taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. Taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. . Conversely, 32 states levy graduated-rate income taxes, with the number of brackets varying widely by state. Hawaii has 12 brackets, the most in the country.

- States’ approaches to income taxes vary in other details as well. Some states double their single-bracket widths for married filers to avoid the “marriage penalty.” Some states index tax brackets, exemptions, and deductions for inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. ; many others do not. Some states tie their standard deductions and personal exemptions to the federal tax code, while others set their own or offer none at all.

Individual income taxes are a major source of state government revenue, accounting for 37 percent of state tax collections.[1] Their prominence in public policy considerations is further enhanced by the fact that individuals are actively responsible for filing their income taxes, in contrast to the indirect payment of sales and excise taxes.

Forty-three states levy individual income taxes. Forty-one tax wage and salary income, while two states–New Hampshire and Tennessee–exclusively tax dividend and interest income. Seven states levy no income tax at all. Tennessee is currently phasing out its Hall Tax (income tax applied only to dividends and interest income) and is scheduled to repeal its income tax entirely for tax years beginning January 1, 2021.[2]

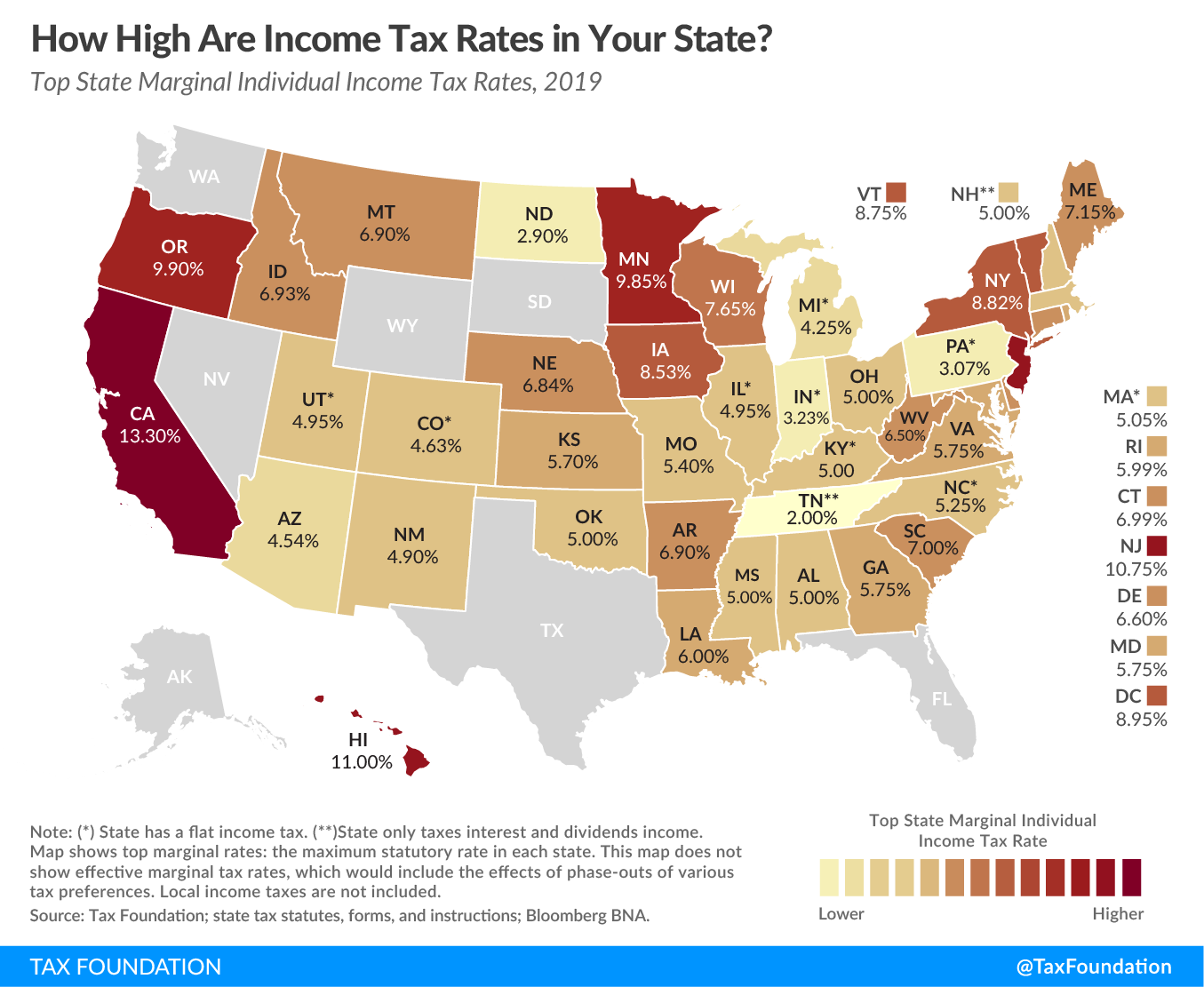

Of those states taxing wages, nine have single-rate tax structures, with one rate applying to all taxable income. Conversely, 32 states levy graduated-rate income taxes, with the number of brackets varying widely by state. Kansas, for example, imposes a three-bracket income tax system. At the other end of the spectrum, Hawaii has 12 brackets, and California has 10. Top marginal rates range from North Dakota’s 2.9 percent to California’s 13.3 percent.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeIn some states, a large number of brackets are clustered within a narrow income band; Georgia’s taxpayers reach the state’s sixth and highest bracket at $7,000 in annual income. In the District of Columbia, the top rate kicks in at $1 million, as it does in California (when the state’s “millionaire’s tax” surcharge is included). New York and New Jersey’s top rates kick in at even higher levels of marginal income: $1,077,550 and $5 million, respectively.

States’ approaches to income taxes vary in other details as well. Some states double their single-bracket widths for married filers to avoid the “marriage penalty.” Some states index tax bracketsA tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. , exemptions, and deductions for inflation; many others do not. Some states tie their standard deductions and personal exemptions to the federal tax code, while others set their own or offer none at all. In the following table, we provide the most up-to-date data available on state individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. rates, brackets, standard deductions, and personal exemptions for both single and joint filers.

The 2017 federal tax reform law increased the standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. Taxpayers who take the standard deduction cannot also itemize their deductions; it serves as an alternative. (set at $12,200 for single filers and $24,400 for joint filers in 2019), while suspending the personal exemption by reducing it to $0 through 2025. Because many states use the federal tax code as the starting point for their own standard deduction and personal exemption calculations, some states that are coupled to the federal tax code updated their conformity statutes in 2018 to either adopt federal changes or retain their previous deduction and exemption amounts.

Notable Individual Income Tax Changes in 2019

Several states changed key features of their individual income tax codes between 2018 and 2019. These changes include the following:

- As part of a broader tax reform package, Kentucky replaced its six-bracket graduated-rate income tax, which had a top rate of 6 percent, with a 5 percent single-rate tax.[3]

- New Jersey created a new top rate of 10.75 percent for marginal income $5 million and above.[4]

- In adopting legislation to conform to changes in the federal tax code, Vermont eliminated its top individual income tax bracket and reduced the remaining marginal rates by 0.2 percentage points across the board.[5]

- Iowa adopted comprehensive tax reform legislation with tax changes that phase in over time. For tax year 2019, income tax rates are reduced across the board, and in 2023, subject to revenue triggers, nine brackets will be consolidated into four, with the top rate reduced to 6.5 percent.[6]

- Idaho adopted conformity and tax reform legislation that included a 0.475 percentage point across-the-board income tax rate reduction.[7]

- Missouri eliminated one of its income tax brackets and reduced the top rate from 5.9 to 5.4 percent as part of a broader conformity and tax reform effort.[8]

- Utah reduced its single-rate individual income tax from 5 to 4.95 percent.[9]

- Arkansas is unique among states in that it has three entirely different rate schedules depending on a taxpayer’s total taxable income. In 2018, Arkansas adopted low-income tax relief legislation that reduced marginal rates in the lowest-income schedule, as well as the lowest rate in the next income schedule.[10]

- Georgia reduced its top marginal individual income tax rate from 6 to 5.75 percent as part of a conformity measure, but this provision is set to expire at the end of 2025 when income tax changes are scheduled to sunset at the federal level.[11]

- North Carolina’s flat income tax was reduced from 5.499 to 5.25 percent.[12]

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeNotes

[1] U.S. Census Bureau, “State & Local Government Finance,” Fiscal Year 2016, https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/2016/econ/local/public-use-datasets.html.

[2] Tennessee Department of Revenue, “Hall Income Tax Notice,” May 2017. https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/revenue/documents/notices/income/income17-09.pdf.

[3] Morgan Scarboro, “Kentucky Legislature Overrides Governor’s Veto to Pass Tax Reform Package,” Tax Foundation, April 16, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/kentucky-tax-reform-package/.

[4] Ben Strachman and Scott Drenkard, “Business and Individual Taxpayers See No Reprieve in New Jersey Tax Package,” Tax Foundation, July 3, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/individual-income-tax-corporate-tax-hike-new-jersey/.

[5] Jared Walczak, “Toward a State of Conformity: State Tax Codes a Year After Federal Tax Reform,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 28, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/state-conformity-one-year-after-tcja/.

[6] Jared Walczak, “What’s in the Iowa Tax Reform Package,” Tax Foundation, May 9, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/whats-iowa-tax-reform-package/.

[7] Katherine Loughead, “Five States Accomplish Meaningful Tax Reform in the Wake of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Tax Foundation, July 23, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/five-states-accomplish-meaningful-tax-reform-wake-tax-cuts-jobs-act/.

[8] Jared Walczak, “Toward a State of Conformity: State Tax Codes a Year After Federal Tax Reform.”

[9] Ibid.

[10] Nicole Kaeding, “Tax Cuts Signed in Arkansas,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 2, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-cuts-signed-arkansas/.

[11] Jared Walczak, “Tax Changes Taking Effect January 1, 2019,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 27, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/state-tax-changes-january-2019/.

[12] Ibid.

Share this article