Key Findings

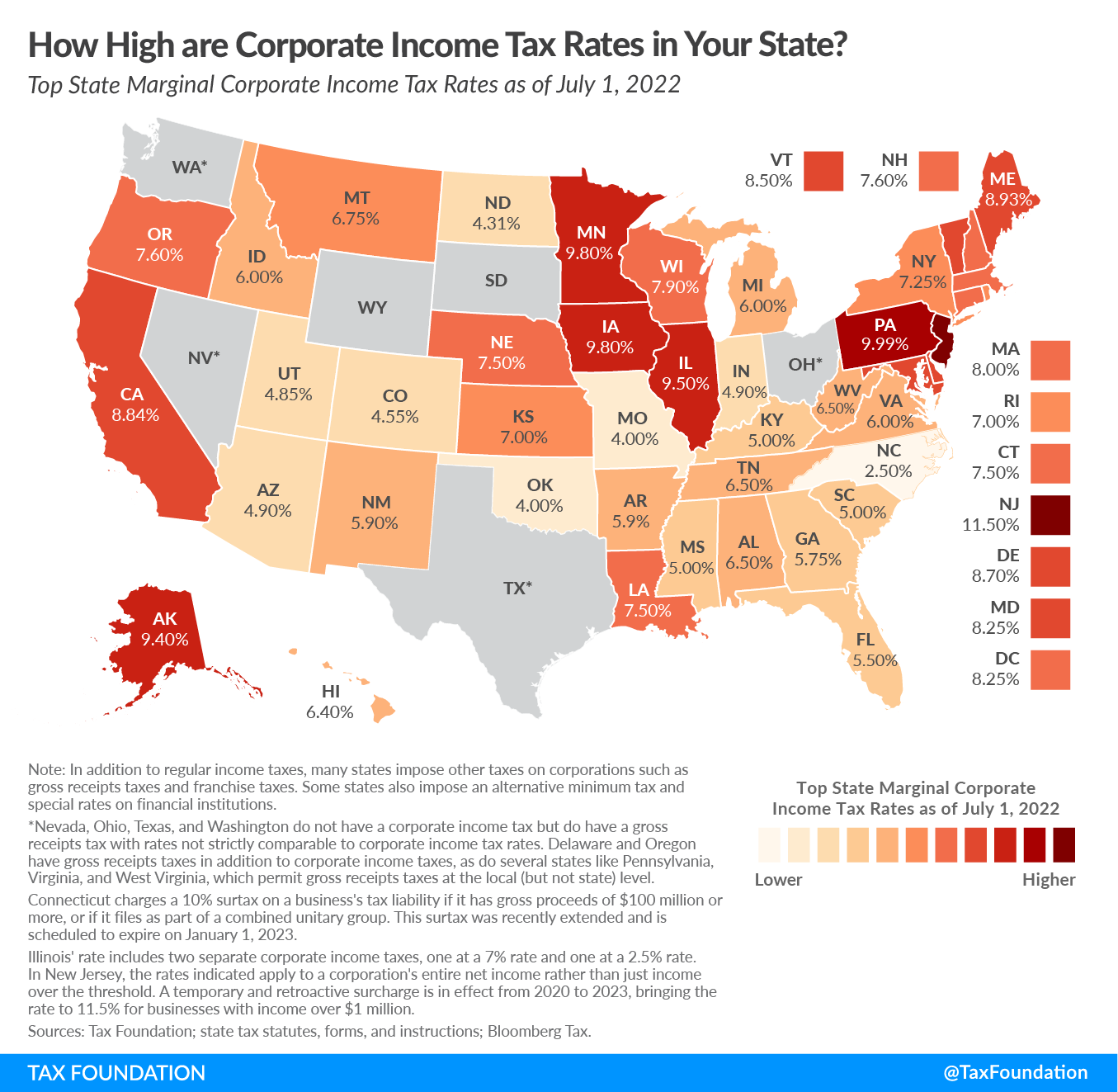

- Forty-four states levy a corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. . Rates range from 2.5 percent in North Carolina to 11.5 percent in New Jersey.

- Six states—Alaska, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania—levy top marginal corporate income taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. rates of 9 percent or higher.

- Eleven states—Arizona, Colorado, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Utah—have top rates at or below 5 percent.

- Nevada, Ohio, Texas, and Washington impose gross receipts taxes instead of corporate income taxes. Gross receipts taxes are generally thought to be more economically harmful than corporate income taxes.

- South Dakota and Wyoming are the only states that levy neither a corporate income nor gross receipts taxGross receipts taxes are applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like compensation, costs of goods sold, and overhead costs. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and applies to transactions at every stage of the production process, leading to tax pyramiding. .

Corporate income taxes are levied in 44 states and DC. Though often thought of as a major tax type, corporate income taxes accounted for an average of just 4.93 percent of state tax collections and 2.26 percent of state general revenue in fiscal year 2020.[1]

New Jersey levies the highest top statutory corporate tax rate at 11.5 percent, followed by Pennsylvania (9.99 percent) and Iowa and Minnesota (both at 9.8 percent). Two other states (Alaska and Illinois) impose rates greater than 9 percent.

Conversely, North Carolina’s flat rate of 2.5 percent is the lowest in the country, followed by rates in Missouri and Oklahoma (both at 4 percent) and North Dakota (4.31 percent). Seven other states impose top rates at or below 5 percent: Colorado (4.55 percent), Arizona and Indiana (4.9 percent), Utah (4.85 percent), and Kentucky, Mississippi, and South Carolina (5 percent).

Nevada, Ohio, Texas, and Washington forgo corporate income taxes but instead impose gross receipts taxes on businesses, which are generally thought to be more economically harmful due to tax pyramidingTax pyramiding occurs when the same final good or service is taxed multiple times along the production process. This yields vastly different effective tax rates depending on the length of the supply chain and disproportionately harms low-margin firms. Gross receipts taxes are a prime example of tax pyramiding in action. and nontransparency.[2] Delaware, Oregon, and Tennessee impose gross receipts taxes in addition to corporate income taxes, as do several states, like Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia, which permit gross receipts taxes at the local (but not state) level. South Dakota and Wyoming levy neither corporate income nor gross receipts taxes, and with the enactment of a budget which includes the multiyear phaseout of its corporate income tax, North Carolina is due to join them by 2030.[3]

Twenty-nine states and the District of Columbia have single-rate corporate tax systems. The greater propensity toward single-rate systems for corporate tax than individual income tax is likely because there is no meaningful “ability to pay” concept in corporate taxation. Jeffrey Kwall, professor of law at Loyola University Chicago School of Law, notes that:

Graduated corporate rates are inequitable—that is, the size of a corporation bears no necessary relation to the income levels of the owners. Indeed, low-income corporations may be owned by individuals with high incomes, and high-income corporations may be owned by individuals with low incomes.[4]

A single-rate system minimizes the incentive for firms to engage in economically wasteful tax planning to mitigate the damage of higher marginal tax rates that some states levy as taxable income rises.

Notable State Corporate Income Tax Changes in 2022

Several states implemented corporate income tax rate changes over the past year, among other revisions and reforms. Notable changes for tax year 2022 include:

- Arkansas saw its previous top rate of 6.2 percent drop to 5.9 percent on January 1, as the final phase of tax reforms started in 2019 kicked in.

- Florida’s corporate tax rate dropped to 3.353 percent in 2021 because its net income tax revenues exceeded projections that year. However, this reduction was only temporary, and the rate returned to 5.5 percent as of January 1.[5]

- Among other reforms, Idaho’s legislature reduced the state’s corporate income tax from 6.925 percent to 6.0 percent.[6]

- Indiana’s final scheduled rate reduction from 5.25 percent to 4.9 percent kicked in on July 1, 2021.[7]

- Louisiana lawmakers’ comprehensive tax reform package, which was approved by voters, includes consolidating the state’s five corporate income tax bracketsA tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. into three and reducing the top rate from 8 to 7.5 percent as of January 1, 2022.[8]

- After increasing the exemption by $1,000 a year since 2018, Mississippi completed the phaseout of its 3 percent corporate income tax bracket as of January 1. The 4 and 5 percent brackets remain in place.[9]

- Nebraska’s top marginal rate lowered from 7.81 to 7.5 percent as a result of Legislative Bill 432, with a further reduction to 7.25 percent scheduled for 2023.[10]

- New Hampshire’s biennial budget reduced the state’s Business Profits Tax (BPT), its corporate income tax, from 7.7 to 7.6 percent. That same legislation also reduced the Business Enterprise Tax (BET)—which is similar to a value-added tax—from 0.6 to 0.55 percent.[11]

- In addition to the previously flat rate of 6.5 percent, New York lawmakers created a second, higher corporate income tax bracket of 7.25 for companies making over $5 million.[12]

- Oklahoma reduced its corporate income tax rate from 6 to 4 percent, tying Missouri for the second-lowest rate in the nation.[13]

| State | Rates | Brackets | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 6.5% | > | $0 |

| Alaska | 0.0% | > | $0 |

| 2.0% | > | $25,000 | |

| 3.0% | > | $49,000 | |

| 4.0% | > | $74,000 | |

| 5.0% | > | $99,000 | |

| 6.0% | > | $124,000 | |

| 7.0% | > | $148,000 | |

| 8.0% | > | $173,000 | |

| 9.0% | > | $198,000 | |

| 9.4% | > | $222,000 | |

| Arizona | 4.9% | > | $0 |

| Arkansas | 1.0% | > | $0 |

| 2.0% | > | $3,000 | |

| 3.0% | > | $6,000 | |

| 5.0% | > | $11,000 | |

| 5.9% | > | $25,000 | |

| California | 8.84% | > | $0 |

| Colorado | 4.55% | > | $0 |

| Connecticut (a) | 7.50% | > | $0 |

| Delaware (b) | 8.7% | > | $0 |

| Florida | 5.5% | > | $0 |

| Georgia (c) | 5.75% | > | $0 |

| Hawaii | 4.4% | > | $0 |

| 5.4% | > | $25,000 | |

| 6.4% | > | $100,000 | |

| Idaho | 6.0% | > | $0 |

| Illinois. (d) | 9.5% | > | $0 |

| Indiana | 4.9% | > | $0 |

| Iowa | 5.5% | > | $0 |

| 9.0% | > | $100,000 | |

| 9.8% | > | $250,000 | |

| Kansas | 4.0% | > | $0 |

| 7.0% | > | $50,000 | |

| Kentucky | 5.0% | > | $0 |

| Louisiana | 3.5% | > | $0 |

| 5.5% | > | $50,000 | |

| 7.5% | > | $150,000 | |

| Maine | 3.50% | > | $0 |

| 7.93% | > | $350,000 | |

| 8.33% | > | $1,050,000 | |

| 8.93% | > | $3,500,000 | |

| Maryland | 8.25% | > | $0 |

| Massachusetts | 8.0% | > | $0 |

| Michigan | 6.0% | > | $0 |

| Minnesota | 9.8% | > | $0 |

| Mississippi (e) | 4.0% | > | $5,000 |

| 5.0% | > | $10,000 | |

| Missouri | 4.0% | > | $0 |

| Montana | 6.75% | > | $0 |

| Nebraska | 5.58% | > | $0 |

| 7.50% | > | $100,000 | |

| Nevada | (b) | ||

| New Hampshire | 7.6% | > | $0 |

| New Jersey (f) | 6.5% | > | $0 |

| 7.5% | > | $50,000 | |

| 9.0% | > | $100,000 | |

| 11.5% | > | $1,000,000 | |

| New Mexico | 4.8% | > | $0 |

| 5.9% | > | $500,000 | |

| New York | 6.50% | > | $0 |

| 7.25% | > | $5,000,000 | |

| North Carolina | 2.5% | > | $0 |

| North Dakota | 1.41% | > | $0 |

| 3.55% | > | $25,000 | |

| 4.31% | > | $50,000 | |

| Ohio | (b) | ||

| Oklahoma | 4.0% | > | $0 |

| Oregon (a) | 6.6% | > | $0 |

| 7.6% | > | $1,000,000 | |

| Pennsylvania | 9.99% | > | $0 |

| Rhode Island | 7.0% | > | $0 |

| South Carolina | 5.0% | > | $0 |

| South Dakota | None | ||

| Tennessee (b) | 6.5% | > | $0 |

| Texas | (b) | ||

| Utah | 4.85% | > | $0 |

| Vermont | 6.0% | > | $0 |

| 7.0% | > | $10,000 | |

| 8.5% | > | $25,000 | |

| Virginia | 6.0% | > | $0 |

| Washington | (b) | ||

| West Virginia | 6.5% | > | $0 |

| Wisconsin | 7.9% | > | $0 |

| Wyoming | None | ||

| Washington, D.C. | 8.25% | > | $0 |

|

(a) Connecticut charges a 10% surtax on a business’s tax liability if it has gross proceeds of $100 million or more, or if it files as part of a combined unitary group. This surtax was recently extended and is scheduled to expire on January 1, 2023. (b) Nevada, Ohio, Texas, and Washington do not have a corporate income tax but do have a gross receipts tax with rates not strictly comparable to corporate income tax rates. Delaware, Oregon, and Tennessee have gross receipts taxes in addition to corporate income taxes, as do several states like Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia, which permit gross receipts taxes at the local (but not state) level. (c) Georgia’s corporate income tax rate will revert to 6% on January 1, 2026. (d) Illinois’ rate includes two separate corporate income taxes, one at a 7% rate and one at a 2.5% rate. (e) Mississippi finished phasing out its 3 percent bracket at the start of 2022. (f) In New Jersey, the rates indicated apply to a corporation’s entire net income rather than just income over the threshold. A temporary and retroactive surcharge is in effect from 2020 to 2023, bringing the rate to 11.5% for businesses with income over $1 million. Note: In addition to regular income taxes, many states impose other taxes on corporations such as gross receipts taxes and capital stock taxes. Some states also impose an alternative minimum tax and special rates on financial institutions. Sources: Tax Foundation; state tax statutes, forms, and instructions; Bloomberg Tax. |

|||

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe[1] U.S. Census Bureau, “2020 Annual Survey of State Government Finances Tables,” https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/econ/state/historical-tables.html.

[2] Justin Ross, “Gross Receipts Taxes: Theory and Recent Evidence,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 6, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/gross-receipts-taxes-theory-and-recent-evidence/.

[3] Katherine Loughead, “North Carolina Reinforces Its Tax Reform Legacy,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 3, 2021, https://www.taxfoundation.org/north-carolina-tax-reform-2021/.

[4] Jeffrey L. Kwall, “The Repeal of Graduated Corporate Tax Rates,” Tax Notes, June 27, 2011, 1395.

[5] Timothy Vermeer, “Florida Lawmakers Should Provide Certainty Around the State’s Corporate Income Tax Rate Reduction,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 1, 2021, https://www.taxfoundation.org/florida-corporate-income-tax/.

[6] Katherine Loughead and Timothy Vermeer, “States Respond to Strong Fiscal Health with Income Tax Reforms,” July 15, 2021, https://www.taxfoundation.org/2021-state-income-tax-cuts/.

[7] Scott Drenkard, “Indiana’s 2014 Tas Package Continues State’s Pattern of Year Over Year Improvements,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 7, 2014, https://www.taxfoundation.org/indiana-s-2014-tax-package-continues-state-s-pattern-year-over-year-improvements/.

[8] Katherine Loughead and Timothy Vermeer, “States Respond to Strong Fiscal Health with Income Tax Reforms.”

[9] Joseph Bishop-Henchman, “Mississippi Approves Franchise Tax Phasedown, Income Tax Cut,” Tax Foundation, May 16, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/mississippi-approves-franchise-tax-phasedown-income-tax-cut/.

[10] Katherine Loughead and Timothy Vermeer, “States Respond to Strong Fiscal Health with Income Tax Reforms.”

[11] Id.

[12] Janelle Cammenga and Jared Walczak, 2022 State Business Tax Climate Index, Tax Foundation, Dec. 16, 2021, https://files.taxfoundation.org/20211215173528/2022-State-Business-Tax-Climate-Index.pdf#page=6.

[13] Katherine Loughead and Timothy Vermeer, “States Respond to Strong Fiscal Health with Income Tax Reforms.”

Share this article