Key Findings

-

We analyze four options for changing the taxation of U.S. muiltinationals: the full Biden administration proposal raises the federal corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. liabilities of U.S. multinationals by $1.32 trillion over a decade; a partial version raises $580 billion; making GILTI consistent with Pillar 2 raises $106 billion; and a revenue-neutral option to fix unintended issues with GILTI.

-

All four of these options would raise taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. es on the foreign activities of U.S. multinationals.

-

The effect of the Biden administration’s proposals would be the most extreme, imposing a 7.8 percent surtaxA surtax is an additional tax levied on top of an already existing business or individual tax and can have a flat or progressive rate structure. Surtaxes are typically enacted to fund a specific program or initiative, whereas revenue from broader-based taxes, like the individual income tax, typically cover a multitude of programs and services. on the foreign profits of U.S. multinationals in addition to an average foreign tax rate of 12.5 percent, resulting in a combined tax rate of 20.3 percent. This would be significantly higher than combined tax rates under current law (15.3 percent) and under the other proposals (16.3-17.6 percent).

-

Both the full and partial versions of the Biden administration’s proposals would increase profits shifted out of the U.S. on net. Making GILTI resemble Pillar 2 would have smaller effects on profit shiftingProfit shifting is when multinational companies reduce their tax burden by moving the location of their profits from high-tax countries to low-tax jurisdictions and tax havens. .

-

Other countries raising their effective tax rates to 15 percent in response to the OECD’s proposed minimum tax would substantially reduce U.S. corporate tax revenues under all these proposals, but much less under current law.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Overview of International Tax Policy

- Current Taxation of U.S. Multinationals

- Biden Administration Proposals

- Other Proposals

- Methodology

- CFC Calculations

- Parent Taxable Income Calculations

- Indirect Expense Allocation Calculations

- Foreign Tax Credit Calculations

- Other Calculations

- Profit-Shifting Response

- Results

- Results for Main Options

- Industry-Level Analysis

- Profit-Shifting Responses to International Tax Changes

- Foreign Country Responses to Pillar 2

- Results for Other Options

- Conclusion

Launch U.S. International Tax Reform Resource Center

Introduction

U.S. multinationals represent an important segment of business activity in the United States. Although only a small share of the total number of businesses, these firms are disproportionately larger than purely domestic firms. Based on data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), in 2018, U.S. multinationals contributed 41.5 percent of private business capital expenditures and employed 28.6 million people in the U.S. They constitute an even larger share of high value-added activity, engaging in 74.2 percent of business research and development in the U.S. and earning 76.2 percent of all corporate income. From IRS corporate tax data for 2016, they contributed 63.6 percent of all federal corporate tax revenues.

Unlike domestic businesses, multinationals have greater flexibility to shift their profits to lower-tax countries and to locate investments in jurisdictions with favorable tax treatment. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) reformed the taxation of the foreign profits of U.S. multinationals with the goal of reducing or eliminating profit shifting incentives, centered on the Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) provisions. However, some aspects of the TCJA’s international tax provisions have faced criticism, including over unanticipated interactions between provisions. The Overview below explains these issues in greater detail.

In this context, it is important to understand how proposals to change international tax rules would affect U.S. multinationals. The Biden administration’s “Made in America Tax Plan” would substantially raise taxes on the foreign and domestic activities of U.S. multinationals, and Congress may consider similar approaches to raising revenue.[1] Meanwhile, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has advanced its proposals to reshape the international tax system for large multinational enterprises (MNEs).[2] The OECD proposal consists of two parts: Pillar 1 would change the location of some taxable profits to the location of a firm’s customers, and Pillar 2 would impose a per-country minimum tax of at least 15 percent. We explore the different proposals for restructuring international tax ruleInternational tax rules apply to income companies earn from their overseas operations and sales. Tax treaties between countries determine which country collects tax revenue, and anti-avoidance rules are put in place to limit gaps companies use to minimize their global tax burden. s in the Overview.

A previous paper used Tax Foundation’s new Multinational Tax Model to explore the potential effects on U.S. multinationals of the “Made in America Tax Plan.”[3] Findings in that paper showed that the proposal would substantially raise taxes on the foreign and domestic activities of U.S. multinationals. While it would reduce offshoring incentives as the administration has claimed, those incentives under current law are small, and so this effect would be trivial. The plan would impose a substantial surtax on the foreign activities of U.S. multinationals, putting them at a competitive disadvantage relative to foreign corporations. However, it would increase the tax rate on domestic activity by more, resulting in a net increase in profits shifted out of the U.S.

This paper uses an expanded and improved version of the Multinational Tax Model. This new version includes separate calculations by industry and can model more tax proposals, as explained in the Methodology section below.

We use this enhanced model to analyze different proposals for restructuring the taxation of U.S. multinationals. We focus on four main options:

- The Biden administration’s proposals

- A partial version of the administration’s proposals

- A revenue-neutral fix to problems with GILTI

- Making GILTI resemble Pillar 2

The analysis of the Biden administration’s proposals provides an update on the previous analysis incorporating modeling improvements and recent changes to the administration’s proposals. The partial version reflects that the administration’s large tax hikes may have difficulty getting approval in Congress.[4] Accordingly, this proposal uses more moderate changes to the corporate tax rate and international tax provisions. The third option addresses problems with the design of GILTI that impose higher tax burdens than anticipated. This option trades off reducing these unintended tax burdens in exchange for a higher tax rate on GILTI, to produce a revenue-neutral policy over the 10-year budget window. Finally, our fourth option considers the effects of making the GILTI provisions conform to the minimum taxes that would be imposed under the OECD’s proposal.

The Biden administration’s proposals would raise the federal corporate income tax liabilities of U.S. multinationals by $1.32 trillion over a decade, and the partial version of this would raise these tax liabilities by $580 billion over a decade. Making GILTI conform to Pillar 2 of the OECD’s proposal would raise $106 billion over a decade.

Unlike most other countries, the U.S. imposes significant residual taxes on the foreign activities of its multinationals, which we estimate at 2.9 percent of those foreign profits under current law, on top of foreign taxes on that activity. All four of the options described above would raise this residual U.S. tax, but the Biden administration’s proposal would be the most extreme, raising it to 7.8 percent. This would create a substantial disadvantage to U.S. companies operating abroad; the same activities would face taxes 63 percent higher under U.S. ownership than under foreign ownership.

We also consider potential behavioral responses to these tax changes. The full and partial versions of the Biden administration’s proposals would increase profit shifting out of the U.S. on net. The revenue-neutral GILTI fix would reduce profit shifting, and Pillar 2 compliance would slightly increase profit shifting.

It is also important to consider the behavior of other countries. If low-tax countries raise their effective corporate tax rates to 15 percent—as intended under the OECD proposal—this has two potential effects on U.S. tax revenue. Higher foreign tax rates reduce the incentive to shift profits out of the U.S., increasing the domestic corporate tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. . However, because the U.S. imposes residual taxes on these foreign profits, higher foreign taxes on U.S. multinationals are partially offset by a higher foreign tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. (FTC). On net, the second effect dominates; if foreign countries raise their tax rates to a 15 percent minimum, the U.S. loses tax revenue. This effect is small under current law but is much larger under all four options.

Finally, we provide estimates of the effects on corporate tax liabilities of various options for changing taxes on U.S. multinationals, as a tool for policymakers considering reforms to these tax provisions.

Overview of International Tax Policy

Historically, most countries’ tax systems have generally relied on source-based taxation, imposing taxes in the location where productive activity occurs. However, until 2017, the U.S. system relied on a hybrid between source and residence taxation. The old U.S. system taxed both foreign and domestic corporations on profits produced in the U.S., but it also imposed residual taxes on the foreign profits of U.S. multinationals. Profits of U.S. multinationals booked in their controlled foreign corporations (CFCs) could be included in the parent companies’ taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. through two methods: passive CFC profits—such as interest and royalty income—were automatically included in their parent companies’ taxable income via subpart F rules, but active CFC profits were only subject to tax when repatriated to the parent as a dividend. By not paying dividends to their parent companies, CFCs could defer these U.S. taxes, potentially indefinitely.

Unlike domestic corporations, multinationals have flexibility to take advantage of cross-country tax differences to reduce their tax burdens, such as by engaging in profit shifting to move the location of reported profits from high-tax to low-tax countries. Profit shifting often relies on intangible assets, such as patents.[5] The physical location of an idea is irrelevant to its use, but the legal location of the entity that owns the patent matters for where the profits it generates are taxed. By having patents and other intangible assets owned by affiliates in a tax haven or other low-tax country, a firm could avoid taxes on much of its profits. In addition to shifting profits through intangible assets, firms could often shift profits using the location of debt by concentrating borrowing in affiliates in high-tax countries, where the tax shield from debt is larger.[6]

In addition to shifting profits to low-tax jurisdictions, firms can also choose the location of discrete investments to reduce their tax burdens. Devereux and Griffith found that this extensive margin location decision is sensitive to effective average tax rates (EATRs), a forward-looking measure of the taxes on a profitable project over that project’s lifetime.[7]

In addition to these general multinational responses to tax policies, the U.S. tax system prior to 2017 faced two specific critiques. First, the tax penalty for repatriating profits to the U.S. parent company created a lockout effect, whereby U.S. multinationals could not access the accumulated foreign profits “trapped” in their CFCs without incurring sizable tax liabilities.[8] Furthermore, the U.S. corporate tax rate of 35 percent plus state taxes significantly exceeded those in other developed countries; the OECD average statutory corporate tax rate was 24 percent in 2017.[9]

This high tax rate exacerbated profit shifting and offshoring incentives, and imposing that high rate on some foreign activities of U.S. multinationals put them at a competitive disadvantage. This competitive disadvantage prompted a wave of inversions, in which U.S. multinationals used mergers with foreign firms to shift their legal residence to lower-tax countries.[10]

Current Taxation of U.S. Multinationals

The TCJA sought to address these issues with three major changes to the taxation of U.S. multinationals. First, it reduced the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent. This substantially reduced profit shifting incentives and the competitive disadvantage of the U.S. tax system. Including state and local taxes, the combined U.S. corporate income tax rate of 25.8 percent as of 2020 was close to the OECD average of 23.5 percent. Second, it switched from taxing active CFC income only when repatriated to the parent company to taxing part of that income when earned but at a lower rate, using the new Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) rules. Third, it established a lower tax rate on intangible income reported in the U.S. via the Foreign-Derived Intangible Income (FDII) deduction.

The GILTI and FDII provisions were intended to substantially reduce or eliminate profit-shifting incentives for U.S. multinationals. GILTI was intended to impose a minimum tax on intangible income booked in foreign countries, and FDII provides a reduced tax rate on income from foreign sources booked in the U.S. To avoid complications in defining intangible income, both provisions instead exempted 10 percent of tangible assets, a presumed normal rate of return on these assets; this is known as the qualified business asset investment (QBAI) exemption. GILTI aimed to impose a minimum tax on this income between 10.5 and 13.125 percent (rising to a range of 13.125 to 16.4 percent in 2026) using a 50 percent deduction (37.5 percent as of 2026), and FDII to produce a reduced rate of 13.125 percent (rising to 16.4 percent in 2026) using a 37.5 percent deduction (21.875 percent as of 2026).

These two provisions substantially reduced profit shifting out of the U.S. A previous Tax Foundation analysis of U.S. multinationals found that the TCJA essentially eliminated the tax advantage to shifting profits abroad.[12] A recent analysis by the Penn Wharton Budget Model found that profit-shifting behavior has decreased as well, estimating that multinationals brought at least $140 billion in profits back to the U.S. from 2018 to 2020.[13]

Although it substantially reduced profit shifting, the design of the GILTI provisions has faced several critiques.[14] The Biden administration has heavily criticized inadvertent incentives for offshoring of tangible assets created by the 10 percent exemptions for them in FDII and GILTI.[15] Essentially, by locating tangible capital with a rate of return below 10 percent in a foreign country instead of in the U.S., the higher tangible capital abroad reduces CFC income subject to GILTI while the lower tangible capital in the U.S. increases domestic income eligible for the FDII deduction. A previous analysis of tax incentives for U.S. multinationals found that forward-looking effective average tax rates on tangible investment show that this tax advantage to offshoring from the QBAI exemptions exists, but it is small and sensitive to assumptions about rates of return on investment.[16] Moreover, this offshoring tax advantage is much smaller now than under pre-TCJA law.

The Biden administration has also criticized cross-crediting under GILTI, in which high taxes paid in high-tax countries can offset low taxes paid in low-tax countries.[17] However, the ability to pool foreign taxes across countries is a deliberate feature of GILTI, so that it targets firms achieving low average tax rateThe average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by taxable income. While marginal tax rates show the amount of tax paid on the next dollar earned, average tax rates show the overall share of income paid in taxes. s on their foreign profits. Pooling foreign taxes when calculating the GILTI foreign tax credit (FTC) also avoids the substantial compliance costs associated with a per-country minimum tax.

Other critiques of GILTI have focused on its interaction with indirect expense allocation rules. On the justification that some domestic expenses support the foreign activities of U.S. multinationals, these rules require that some domestic expenses be reallocated from reducing domestic taxable income to reducing foreign taxable income. Although this does not change overall taxable income, it tightens the FTC limitation, resulting in a firm facing GILTI liabilities even if it faces a high foreign tax rate.

To illustrate this effect, consider the calculation in the following table. Suppose a multinational has $100 of domestic income and $100 of GILTI from its CFCs. The first column presents the firm’s tax calculations without GILTI, the next two columns show how GILTI affects this firm if it has a low tax rate of 5 percent, and the last two columns if the firm faces a higher foreign tax rate of 18 percent. We consider how tax liabilities change if $10 of domestic expenses are allocated to GILTI income. For this calculation, we ignore the FDII deduction and any credits other than the FTC, and we assume all CFC income is active.

| No GILTI | GILTI for low-tax firm | GILTI for high-tax firm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No allocation | With allocation | No allocation | With allocation | ||

|

Inputs |

|||||

| Domestic income | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| GILTI inclusion | – | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Foreign tax rate | – | 5% | 5% | 18% | 18% |

|

GILTI calculation |

|||||

| GILTI taxable income | – | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Taxes paid on GILTI | – | 5 | 5 | 18 | 18 |

| Taxable income | 100 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 |

|

FTC calculation |

|||||

| Reallocated expense | – | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| Income in GILTI basket | – | 50 | 40 | 50 | 40 |

| Credit limitation | – | 10.5 | 8.4 | 10.5 | 8.4 |

| Foreign taxes available for credit | – | 4 | 4 | 14.4 | 14.4 |

| Foreign tax credit | – | 4 | 4 | 10.5 | 8.4 |

|

Tax calculation |

|||||

| Tax before credits | 21 | 31.5 | 31.5 | 31.5 | 31.5 |

| U.S. tax liability | 21 | 27.5 | 27.5 | 21 | 23.1 |

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeWithout GILTI, the firm’s taxable income only comes from its domestic income of $100, producing U.S. tax liability of $21 at the 21 percent tax rate. Under current law, a 100 percent GILTI inclusion generates $50 of GILTI taxable income and total taxable income of $150.

The calculation of the FTC chooses the minimum of foreign taxes available for credit and the credit limitation, which is equal to taxable income in the GILTI basket multiplied by the statutory corporate tax rate of 21 percent. The low-tax firm paid a 5 percent tax rate on $100 of GILTI, of which 80 percent is eligible for the FTC. Because its tax rate is low, the FTC limitation does not bind, so its FTC is also $4. The combination of domestic income, the $50 GILTI taxable income, and the $4 FTC produce a net U.S. tax liability of $27.50. Because the FTC limitation does not bind, indirect expense allocation has no effect.

On the other hand, the high-tax firm facing an 18 percent foreign tax rate in theory should have no GILTI liability. With $50 of GILTI taxable income, its FTC limitation—ignoring expense allocation—is equal to its initial tax from GILTI of $10.50. With foreign taxes available for credit of $14.40 (80 percent of the 18 percent tax on $100 of GILTI), the FTC limitation binds. Although GILTI raised the firm’s initial tax liability before credits by $10.50, this is exactly offset by the FTC, leaving a net tax liability of $21. However, if $10 of domestic expenses are allocated to the GILTI basket, the income reported in the GILTI basket falls to $40, reducing the FTC limitation to $8.40. This firm’s net U.S. tax liability is $23.10, so it has $2.10 of U.S. taxes on its GILTI income even though it faced a high foreign tax rate.

To determine the amount of expenses to reallocate to foreign sources, there are two methods available. Under the water’s edge approach, a multinational would allocate the domestic expense in proportion to the foreign share of some basis. For example, to allocate interest expense, a firm calculates its total equity in related foreign affiliates, divides this by the firm’s total assets to obtain the foreign asset share, and multiplies this foreign share by domestic interest expense. This calculation implicitly assumes that the firm’s entire interest expense to support foreign activity occurs domestically, ignoring any interest expense incurred in the foreign affiliates.

Because firms generally borrow both domestically and in their foreign affiliates, an alternative approach—worldwide expense allocation—would correct for this. Under worldwide expense allocation, the firm would instead split the total domestic and foreign expenses in proportion to the foreign share of basis, but the reallocated amount would be this proportional share of the total expense in excess of the actual foreign expense. The resulting reallocated expense then gets split among subpart F, foreign branch income, foreign dividend income, and deemed intangible income.

As of 2021, firms were supposed to be able to elect whether to use the water’s edge or worldwide approach for expense allocation. However, the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 canceled worldwide interest expense allocation; firms can still use the worldwide method for R&D and stewardship expenses.[18]

Whereas expense allocation imposes a residual tax on firms based on their domestic activities, the lack of carryforwards for unused GILTI FTCs or losses can create GILTI liability on a firm facing a high lifetime foreign tax rate but with temporary fluctuations of its foreign profits and tax rates. Traditionally, firms have been allowed to carry foreign taxes in excess of the limitation forward, and to carry losses forward. A firm’s income or loss and its foreign taxes can fluctuate from year to year due to temporary timing effects, and allowing carryforwards recognizes this and mitigates timing impacts on firms’ U.S. taxes. GILTI does not allow carryforwards of CFC losses or of unused foreign taxes (in excess of the limit). A firm with a foreign tax rate that fluctuates between 10 and 20 percent will owe taxes on GILTI in low-tax years but be unable to use all its foreign taxes for the FTC in high-tax years.

Biden Administration Proposals

The Biden administration has argued that U.S. multinationals do not pay their “fair share” of taxes. Accordingly, the administration’s proposals, both the initial version in the “Made in America Tax Plan” and the proposal as described in the Green Book, would raise taxes substantially on activities of U.S. multinationals.[19] They would raise the corporate income tax rate to 28 percent and raise the GILTI minimum rate to 21 percent (by raising the GILTI inclusion rate to 75 percent). These proposals would also tighten GILTI by repealing the QBAI exemption for tangible assets and requiring that GILTI and the FTCs for GILTI and foreign branch income be calculated on a country-by-country basis.

We assume that the repeal of the QBAI exemption also repeals the add-back of interest expense, as in the Removing Incentives for Outsourcing Act (S. 20, 2021).[20] The proposals would also repeal the FDII deduction, although the Green Book proposed to replace it with an unspecified R&D incentive. As this replacement has not been described, we do not model it. The Green Book also proposed to apply the section 265 denial of deductions to exempt foreign income, and this would apply to the “excluded” portion of GILTI (25 percent in the Biden proposal).

All these provisions would raise taxes on U.S. multinationals. The higher domestic corporate tax rate and repeal of FDII would raise marginal tax rateThe marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. s on firms’ income booked domestically, and the 21 percent GILTI rate would raise marginal tax rates on their income booked in CFCs. Repealing the QBAI exemption would broaden the base of GILTI to no longer apply only to intangible income, and paired with FDII repeal it would essentially eliminate the offshoring incentive the administration has focused on. The country-by-country GILTI calculations would eliminate cross-crediting.

However, the administration’s proposals would exacerbate the timing problems of GILTI and the distortions from expense allocation. With full carryforwards, multinationals would essentially be able to pool their income and losses and their foreign taxes across countries and over time. Under current law without carryforwards, they cannot pool over time, resulting in timing distortions. Under the administration’s proposals, they would be not able to pool over time or across countries, further exacerbating the tax consequences of temporary shocks.

The Green Book proposal for denial of deductions is based on complexities in the expense allocation rules. A multinational is supposed to allocate certain deductions—interest expense, R&D expense, and stewardship expenses—to activities in its CFCs and foreign branches. The portion allocated to CFCs gets further split into four categories: subpart F income, which is allocated to the passive foreign income basket; included GILTI income, allocated to the GILTI basket; excluded GILTI income; and dividends from 20-percent owned related foreign corporations.

The portion allocated to excluded GILTI income does not affect the tax liability of the parent company, nor does the portion allocated to these dividends. The Green Book proposal would instead require that the deduction allocated to these exempt income groups be added back to U.S. taxable income. While that could make sense for excluded GILTI income, doing so for exempt dividends is at odds with how the U.S. taxes foreign income of its multinationals. By design, the U.S. system switched from taxing active CFC income when repatriated as dividends to when it occurs, so dividends from CFCs should no longer affect their parents’ tax liabilities. By denying deductions in proportion to exempt dividend income from CFCs, the proposal would conflict with the intended design of the tax system and would re-create part of the lockout effect on CFC profits eliminated by the TCJA.

A previous analysis of the “Made in America Tax Plan” found that the proposal would increase profit shifting on net, contrary to the administration’s claim.[21] Essentially, the 7 percentage point increase in the corporate tax rate would increase domestic taxes by more than their tax hikes on foreign activity, and repeal of FDII would exacerbate this. The proposal would essentially eliminate offshoring incentives for tangible assets, although the tax hikes on CFC activity would put U.S. multinationals at a substantial tax rate disadvantage relative to foreign ownership of the same activities.

Other Proposals

The Biden administration’s proposals are not the only ones under consideration. A proposal from Senators Ron Wyden (D-Oregon), Mark Warner (D-Virginia), and Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) provides an alternative, less extreme proposal for raising taxes on U.S. multinationals.[22] The proposal would raise the GILTI rate an unspecified amount, and it would repeal the QBAI exemptions for GILTI and FDII. To reduce cross-crediting, they proposed to either switch to a country-by-country calculation for GILTI or to apply GILTI only to low-tax countries through a mandatory high-tax exclusion.

Beyond the U.S. debate, the OECD Inclusive Framework of more than 130 countries has produced proposals for the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project.[23] These proposals, which would only apply to the largest multinationals, consist of two pillars. Pillar 1 provides nexus rules that would subject some high profits of multinationals to tax based on the location of their sales. Pillar 2 would impose a country-by-country minimum tax on the foreign activities of multinationals with profits above $750 million euros, with a substance exemption of 7.5 percent of tangible assets and payroll for five years and at least 5 percent thereafter.

There are numerous ways GILTI and other international tax rules could be modified to raise more revenue, reduce tax burdens on foreign activities, or fix unintended interactions with other provisions. The Results section below presents the revenue effects of many such reforms and modifications in our analysis.

Methodology

The Multinational Tax Model is structured as a set of representative MNEs in each of 40 industry groups, each of which own a set of CFCs across 74 industries and 48 regions (42 countries and six other regions). The CFCs earn profits, pay foreign taxes, and engage in activity that affects the U.S. tax liabilities of their parent companies. The parent MNEs receive income from CFCs, as well as other sources of domestic and foreign income, and pay federal corporate income taxes. The model is built on data from 2014, the most recent benchmark survey by the BEA on activities of U.S. MNEs.

CFC Calculations

The calculations for CFCs rely on the IRS tables on CFCs, which provide information such as profits, foreign taxes, dividends received and paid, and subpart F income.[24] We supplement this with data from the BEA on real activities of majority-owned foreign affiliates (MOFAs), to estimate tangible assets, R&D, and other measures relevant to tax calculations.[25] Combining these sources, we have 3,456 representative CFCs, one for each country and industry.

The basic calculations for CFCs come largely from pre-TCJA law. We use total profits and the average foreign tax rate in a given country-industry observation to calculate foreign income taxes and profits after tax. We also calculate subpart F income and dividends paid to the parent company based on effective subpart F rates and dividend repatriationTax repatriation is the process by which multinational companies bring overseas earnings back to the home country. Prior to the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the U.S. tax code created major disincentives for U.S. companies to repatriate their earnings. Changes from the TCJA eliminate these disincentives. rates in the data.

We also compute items for the GILTI calculations from CFCs. When GILTI is calculated on a global basis (as under current law) we only need to compute tested CFC income for each CFC observation and the tax rate paid on it. When calculated on a country-by-country basis (as under the Biden administration’s proposals) we compute deemed intangible income and taxes paid on it for each CFC observation, and we compute the GILTI inclusion in taxable income and the GILTI FTC arising from each country-industry observation. For more details on the FTC calculations, see the explanation below.

Under current law, GILTI calculations are prorated based on the parent’s ownership share of a CFC. Accordingly, when attributing CFC tax items to parents, we scale these down so that the total GILTI inclusion in the model matches that in newly released IRS data for 2018.[26]

Parent Taxable Income Calculations

The data for the parent companies combine results from the CFC calculations with the IRS tables on corporations claiming the FTC.[27] These allow us to extract relevant variables by industry, such as assets, receipts, profits before tax, various income from foreign sources (e.g., foreign interest income and foreign branch income), total gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total pre-tax earnings from wages, tips, investments, interest, and other forms of income and is also referred to as “gross pay.” For businesses, gross income is total revenue minus cost of goods sold and is also known as “gross profit” or “gross margin.” , deductions, and adjustments. We supplement this with data from the BEA on real activities of parents of U.S. MNEs to estimate tangible assets, R&D, interest paid, and other measures.[28]

For each parent company, we first extract relevant variables from their constituent CFCs, such as dividends paid to the parent company, gross-up on dividends and subpart F income, and the components for GILTI calculations. If the GILTI FTC is computed by country, we aggregate income and the FTC from GILTI for each country. If not, we aggregate the CFCs’ tested CFC income, tangible assets, interest paid, and taxes paid on tested CFC income. We use these to compute DII and foreign taxes paid on DII. If the GILTI rules impose a mandatory high-tax exemptionA tax exemption excludes certain income, revenue, or even taxpayers from tax altogether. For example, nonprofits that fulfill certain requirements are granted tax-exempt status by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), preventing them from having to pay income tax. , we restrict the aggregation to come from country-industry observations with foreign tax rates below the specified rate for the high-tax exemption.

We then compute initial taxable income in each of five categories: passive foreign income, which consists of foreign interest income, royalty and license fee income, non-CFC dividends and gross-up, gross-up on subpart F income, and (under pre-TCJA law) CFC dividends and the accompanying gross-up; foreign branch income; active foreign income, which includes foreign service income and other foreign income; taxable income from GILTI; and domestic taxable income.

Using initial taxable income in each basket, we then compute the FDII deduction. We compute deduction eligible income by excluding subpart F income, GILTI income, and foreign branch income. Foreign-derived deduction eligible income also excludes the portion of initial domestic taxable income attributable to domestic sales, the share of which we estimate from the share of sales to domestic and foreign parties by U.S. parent companies. We compute FDII as deduction eligible income less 10 percent of tangible assets of the parent, multiplied by the foreign-derived share of deduction eligible income, if this quantity is positive. We then multiply this by the FDII deduction rate and split this deduction among the passive, other, and domestic taxable income baskets. Both the GILTI and FDII calculations exclude foreign oil and gas extraction income under current law.

We then compute taxable income in each basket as initial taxable income in the basket less its allocated FDII deduction. Totaling the taxable income in each basket gives taxable income before the application of the section 163(j) interest limitation, which constrains the interest paid deduction to interest received plus 30 percent of adjusted taxable income, which we define as taxable income adding back interest paid and subtracting interest received (plus depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. for 2018-2021). We add back the disallowed portion of interest paid to get total taxable income.

Indirect Expense Allocation Calculations

We model indirect expense allocation for interest expense and for R&D expense, for which we have data from the BEA. Our calculations omit the allocation of stewardship expenses.

To implement reallocation under the water’s edge method, we compute the domestic and foreign basis for reallocation. For interest expense, foreign basis is equity in related foreign affiliates, and domestic basis is total parent assets less this related party equity. For R&D expense, we use gross foreign income of MOFAs for foreign basis and gross income of the U.S. parent company as domestic basis. The share of the expense to reallocate is the total expense multiplied by the foreign basis and divided by total basis.

For elective worldwide expense allocation, we use the same basis for R&D expense, but we use total CFC assets as the foreign basis for interest expense. Instead of allocating only domestic expense, we apportion the combined domestic and foreign expenses in proportion to the foreign share of total basis. The amount to reallocate is the excess (if positive) of this proportionally apportioned expense over the actual foreign expense incurred. Because the worldwide reallocation is elective, the parent chooses whichever method reallocates the smaller amount.[29]

Once we have determined the amount of expenses to reallocate, we split this into four categories in proportion to gross income in each category. The portion allocated to subpart F income is subtracted from the passive basket for the calculation of the FTC limitation, and the portion allocated to foreign branch income is similarly subtracted from the foreign branch basket. Part is allocated to tested CFC income; this amount is then multiplied by the GILTI inclusion rate and subtracted from the GILTI basket, and the remaining amount (net of the GILTI inclusion rate) is allocated to exempt foreign income and does not affect the FTC calculations. The final portion is allocated to CFC dividends and gross-up, which is also considered exempt foreign income and does not affect FTC calculations.

Under the Biden administration’s proposal for the application of section 265 to exempt foreign income, the portions allocated to exempt GILTI income and exempt CFC dividends would be added back to taxable income, and so would increase tax liabilities.

Foreign Tax Credit Calculations

The FTC calculations are applied for each of the passive, branch, other, and GILTI baskets. If the GILTI FTC is calculated on a per-country basis, then a separate FTC calculation is implemented for each CFC.

Multiplying taxable income in each of these baskets (after indirect expense allocation) by the statutory tax rate gives the FTC limitation for the basket. We compute taxes paid on the income in each basket, and adding foreign taxes carried forward from previous years gives total taxes available for credit. For GILTI calculations, the taxes in this basket are 80 percent of the foreign taxes paid on deemed intangible income. While no foreign taxes may be carried forward for GILTI under current law, we consider proposals allowing it.

Using a representative firm to calculate the FTC is problematic. In the actual calculations, a firm claims the lesser of the limitation or the taxes available for credit. With heterogeneous firms, some will be constrained by the limitation, and others by the taxes available for credit; when aggregating across firms, this produces a total FTC smaller than both the aggregated FTC limitation and the aggregated taxes available for credit. Thus, a representative firm systematically overestimates the value of the FTC relative to aggregating over many heterogeneous firms.

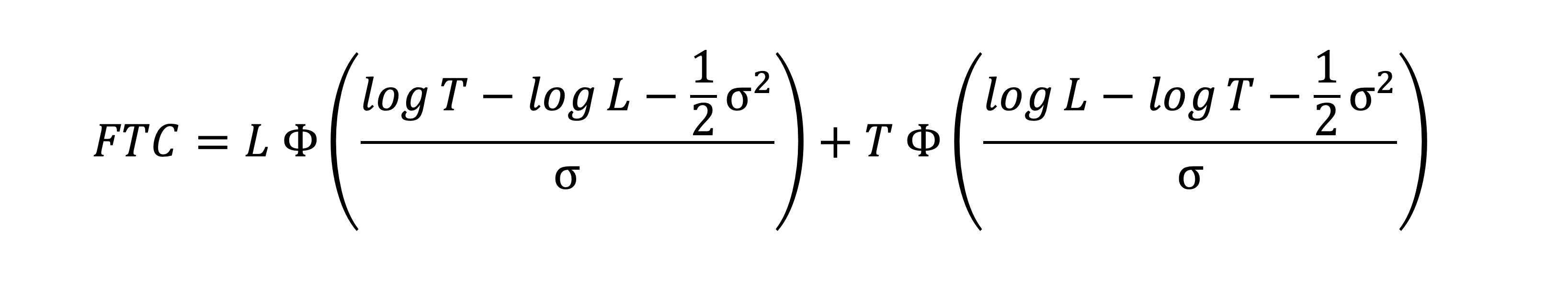

To overcome this problem, we can express the discrepancy between the FTC limitation and the total taxes available for credit as a lognormal-distributed random variable with spread parameter . Under this assumption, we can express the expected value of the FTC, aggregated over many firms, as the following.

In this equation, L is the FTC limitation, T is total taxes available for credit, and Φ is the cumulative distribution function for the standard normal distribution. The spread parameter is calibrated to satisfy this equation in the IRS FTC tables for each industry. When the limitation is much larger than the total taxes available for credit, more weight gets put on the taxes available for credit, and vice versa. The log-standard deviation of causes the FTC to fall below both the aggregated limitation and the aggregated total taxes available for credit.

We apply this formula to each foreign income and tax basket to get the FTC for each basket. Combining these gives the total FTC.

Other Calculations

Multiplying total taxable income by the statutory tax rate gives taxes before credits. Subtracting off the FTC and other tax credits gives total federal corporate income tax liabilities of U.S. MNEs.

In addition to calculating tax liabilities, we also allocate parent tax liabilities arising from CFC activities by computing U.S. taxable income from CFC activities (via subpart F, GILTI as of 2018, and dividends received until 2017) and split the associated FTCs.

Profit-Shifting Response

In theory, profit shifting responds to the marginal tax shield from relocating profits across jurisdictions. For example, if a foreign tax rate is 10 percent and the U.S. tax rate is 21 percent, shifting profits to the foreign jurisdiction provides a tax shield of 11 percentage points.

There are two methods to calculate tax shields: statutory tax rates or average tax rates. Statutory tax rates may be more likely to apply at the margin for some profits, and they do not depend on CFC activities like investment that affect the actual tax liabilities. However, statutory tax calculations miss important complications in international taxes. For example, statutory tax rate calculations are not useful for estimating the incentive effects of cross-crediting under GILTI. Moreover, the definition of the tax base can be more important than the tax rate. For example, Ireland’s 12.5 percent statutory corporate tax rate produces an effective rate of approximately 3 percent on the profits of U.S. MNEs booked in Ireland. Many countries also have special provisions, including tax treaties and favorable patent boxA patent box—also referred to as intellectual property (IP) regime—taxes business income earned from IP at a rate below the statutory corporate income tax rate, aiming to encourage local research and development. Many patent boxes around the world have undergone substantial reforms due to profit shifting concerns. provisions, that produce lower effective tax rates. Because of these limitations, we use average foreign tax rates when calculating profit-shifting incentives.

For the average tax rate calculations, we need to allocate the parent’s tax liabilities arising from CFC activities to each CFC it owns. If GILTI is calculated on a per-country basis, it is straightforward to compute the CFC’s contribution to its parent’s tax liabilities. If GILTI calculations are pooled across countries, we split GILTI income in proportion to the CFC’s contribution to the parent’s tested CFC income, and we split the parent’s GILTI FTC in proportion to foreign taxes paid on its per-country deemed intangible income. The model also computes inclusions via subpart F, dividends paid, and their gross-up, and it allocates the parent’s FTC based on the contributions of these taxes paid to the parent’s total foreign taxes paid.

For the U.S. domestic tax rate, we use the statutory tax rate net of the FDII deduction, and we estimate the probability of FDII eligibility by dividing the actual FDII deduction by the FDII deduction rate and deduction eligible income in each industry. The domestic tax rate less the average foreign tax rate gives the tax shield. We estimate profit shifting using a semi-elasticity of 0.8 with respect to this tax shield, based on the main estimate from Heckemeyer and Overesch.[30]

While the model can also compute investment responses to tax changes, we do not include those in the estimates in this paper.

Results

Our main results focus on four proposals for changing the taxation of U.S. multinationals. The first is the Biden administration’s proposals as described in the Green Book.[31] This proposal raises the corporate tax rate to 28 percent, raises the GILTI minimum rate to 21 percent by raising the GILTI inclusion rate to 75 percent, repeals the QBAI exemption for GILTI, requires that the GILTI FTC be calculated on a per country basis, repeals the FDII deduction, and applies the section 265 denial of deductions to excluded GILTI income and exempt foreign dividends.

The second proposal represents a partial version of the Biden proposals, reflecting potential difficulties getting the full proposal through Congress. Instead of a 28 percent corporate tax rate, this proposal would use a 25 percent rate. Instead of raising the GILTI inclusion rate to 75 percent and repealing FDII, this proposal accelerates the increase in the GILTI inclusion rate and reduction of the FDII deduction rate from 2026 to occur in 2022. At the 25 percent corporate tax rate, these establish a 15.625 percent minimum rate on GILTI and a 19.53 percent FDII rate (also equal to the upper bound on the GILTI rate ignoring expense allocation). It maintains the repeal of the QBAI exemption. However, instead of switching to a per country GILTI calculation, this proposal would use the mandatory high-tax exemption in the proposal from Senators Wyden, Warner, and Brown. Under this approach, tested CFC income and taxes paid on it in countries with effective tax rates on that income above a certain cutoff would be excluded from taxable income and the FTC. The Senators’ proposal leaves the cutoff rate ambiguous; a lower rate reduces cross-crediting (thus reducing the FTC and raising revenue) but also reduces the revenue raised by indirect expense allocation. We use a 22.5 percent cutoff, consistent with the current optional high-tax exemption set at 90 percent of the statutory corporate tax rate.

The third proposal, the revenue-neutral GILTI fix, would alleviate two issues with the design of GILTI that make it a surtax instead of a minimum tax. It would restore worldwide interest expense allocation, and it would allow full GILTI FTC carryforwards. Because each of these provisions loses revenue, it would compensate for these by raising the minimum GILTI rate to 14.1225 percent (instead of 10.5 percent before 2026 and 13.125 percent thereafter).

The final proposal modeled here makes GILTI resemble the OECD’s Pillar 2 proposal. This would raise the GILTI minimum rate to 15 percent, but it would also require substantial changes to the GILTI FTC: repealing the 20 percent haircut on foreign taxes eligible for the GILTI haircut, allowing GILTI FTC carryforwards, and calculating GILTI and its FTCs on a country-by-country basis. It would also switch from a 10 percent GILTI exemption for tangible assets to using exemptions on tangible assets and on payroll, at 7.5 percent rates on each for five years and 5 percent on each thereafter. Although this captures the essence of the OECD’s proposal, there are three potential discrepancies. First, the OECD’s proposal would rely on financial statement income rather than tax income, with unspecified adjustments to reflect timing differences. Second, the OECD’s proposal does not clarify whether the substance carveout for tangible assets and payroll is net of interest paid, as is the case under GILTI, or not. For modeling this, we assume it is net of interest. Third, the OECD proposal would allow losses to be carried forward. We do not have the data to model this change, so the true effect of the proposal may be smaller than our estimated results.

We also consider a set of other options for changing the level of GILTI calculations, changing the structure of the GILTI exemption, and changing indirect expense allocation rules.

Results for Main Options

We first focus on the change in federal corporate income tax liabilities of U.S. multinationals. This is not the same as an actual revenue score, which also includes revenues from non-multinationals and should also reflect offsets from reduced capital gains and dividends for the shareholders of multinationals. A full score should also include the full set of firm responses to tax policies; the estimates here only include the profit-shifting response to tax rate differentials.

Table 2 presents the results for the full Biden administration proposal. The higher corporate tax rate would raise multinationals’ tax liabilities by $753 billion. Raising the GILTI rate to 21 percent would raise $192 billion. At a 21 percent GILTI rate, repealing the QBAI exemption would raise $146 billion, and implementing country-by-country GILTI calculations would raise a further $102 billion. Repealing the FDII deduction would raise their federal tax liabilities by $89 billion. The section 265 denial of deductions against exempt income would raise a further $90 billion. In total, this proposal would raise taxes on U.S. multinationals by $1.37 trillion over a decade.

| Change in Federal Corporate Income Tax Liabilities of U.S. MNEs from Biden Administration Proposal, Billions of Dollars | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provision | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2031 | Total |

| 28% CIT rate | 55.8 | 60.1 | 64.9 | 69.2 | 77.8 | 80.4 | 82.8 | 85.0 | 87.2 | 89.6 | 752.9 |

| + 21% GILTI rate | 22.3 | 23.8 | 25.6 | 27.2 | 14.5 | 14.9 | 15.4 | 15.8 | 16.2 | 16.6 | 192.2 |

| + No QBAI exemption | 11.5 | 12.3 | 13.2 | 14.1 | 14.8 | 15.2 | 15.7 | 16.1 | 16.5 | 16.9 | 146.4 |

| + Country-by-country GILTI | 3.6 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 45.2 |

| + Repeal FDII | 7.9 | 8.9 | 9.9 | 10.7 | 7.0 | 7.2 | 7.4 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 8.1 | 82.6 |

| + Sec. 265 application | 7.7 | 8.2 | 8.8 | 9.4 | 9.7 | 10.0 | 10.3 | 10.6 | 10.9 | 11.1 | 96.7 |

| Total | 108.8 | 117.2 | 126.6 | 135.0 | 128.3 | 132.5 | 136.4 | 140.0 | 143.6 | 147.6 | 1315.9 |

| Note: This table presents the change in federal corporate income tax liabilities of U.S. multinationals in billions of dollars for each provision. All estimates include profit shifting in response to the average tax rate differential with a semi-elasticity of 0.8. | |||||||||||

| Source: Tax Foundation’s Multinational Tax Model. | |||||||||||

Table 3 presents the results for the partial version of the administration’s proposals. Raising the corporate income tax rate to 25 percent raises multinationals’ corporate income tax liabilities by $432 billion over a decade. Accelerating the GILTI and FDII rate changes from 2026 to 2022 raises $56 billion, much smaller than FDII repeal and the 21 percent GILTI rate in the full proposal. Imposing a mandatory high-tax exclusion raises $74 billion, approximately three-fourths of the revenue from switching to a country-by-country GILTI FTC.

Stacked on top of these changes, repealing the QBAI exemption only raises $18 billion. This effect is much smaller than as part of the full Biden administration’s proposal for two reasons. First, the GILTI rate is lower, so changing the GILTI base calculation has a smaller effect. Second, foreign tangible assets of U.S. MNEs are disproportionately located in higher-tax countries relative to the location of profits. Because income from those countries is already being excluded under the mandatory high-tax exclusion, repealing the QBAI exemption has a much smaller effect.

In total, this proposal would raise U.S. multinationals’ federal corporate tax liabilities by $580 billion over a decade, a substantial tax hike but much less extreme than the full Biden administration proposal.

| Change in Federal Corporate Income Tax Liabilities of U.S. MNEs from Partial Proposal, Billions of Dollars | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provision | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2031 | Total |

| 25% CIT rate | 32.0 | 34.5 | 37.3 | 39.7 | 44.6 | 46.1 | 47.5 | 48.7 | 50.0 | 51.3 | 431.7 |

| + Accelerate GILTI/FDII rate changes | 12.2 | 13.2 | 14.3 | 15.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 56.0 |

| + Mandatory high-tax exemption at 22.5% | 5.8 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 7.1 | 7.4 | 7.6 | 7.9 | 8.1 | 8.3 | 8.5 | 73.6 |

| + No GILTI QBAI exemption | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 18.1 |

| Total | 51.5 | 55.5 | 59.9 | 63.8 | 54.2 | 55.8 | 57.4 | 58.9 | 60.4 | 62.0 | 579.5 |

| Note: This table presents the change in federal corporate income tax liabilities of U.S. multinationals in billions of dollars for each provision. All estimates include profit shifting in response to the average tax rate differential with a semi-elasticity of 0.8. | |||||||||||

| Source: Tax Foundation’s Multinational Tax Model. | |||||||||||

Table 4 presents the results for the revenue-neutral GILTI fix. Restoring worldwide interest expense allocation reduces U.S. multinationals’ federal corporate tax liabilities by $23 billion over a decade, and allowing GILTI FTC carryforwards loses a further $47 billion. To pay for these, we set the GILTI minimum rate to 14.1645 percent, which achieves budget neutrality within the 10-year window. However, such a proposal could violate the Byrd rule, as it raises more revenue in the initial years and loses revenue in later years of the budget window and beyond. This timing pattern comes from the higher GILTI rate being a larger increase relative to the current 10.5 percent than to the 13.125 percent beginning in 2026. Additionally, FTC carryforwards accumulate over the first few years of allowing them before stabilizing.

| Change in Federal Corporate Income Tax Liabilities of U.S. MNEs from Revenue-Neutral GILTI Fix, Billions of Dollars | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provision | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2031 | Total |

| Restore worldwide interest expense allocation | -1.8 | -1.9 | -2.1 | -2.2 | -2.4 | -2.4 | -2.5 | -2.6 | -2.6 | -2.7 | -23.3 |

| + Allow GILTI FTC carryforwards | 0.0 | -2.0 | -3.1 | -3.9 | -6.2 | -6.1 | -6.2 | -6.4 | -6.6 | -6.9 | -47.3 |

| + 14.1645% GILTI rate | 10.0 | 10.5 | 11.2 | 11.9 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 70.5 |

| Total | 8.2 | 6.6 | 6.0 | 5.8 | -3.5 | -3.9 | -4.3 | -4.7 | -5.0 | -5.2 | 0.0 |

| Note: This table presents the change in federal corporate income tax liabilities of U.S. multinationals in billions of dollars for each provision. All estimates include profit shifting in response to the average tax rate differential with a semi-elasticity of 0.8. | |||||||||||

| Source: Tax Foundation’s Multinational Tax Model. | |||||||||||

Finally, Table 5 presents the results for making GILTI resemble the OECD’s Pillar 2 proposal. Raising the minimum GILTI rate to 15 percent would raise $99 billion, but removing the 20 percent haircut on foreign taxes paid on GILTI loses $36 billion. On net, a 15 percent minimum tax instead of the GILTI bands under current law (10.5 to 13.125 percent currently, and 13.125 to 16.4 percent beginning in 2026) raises U.S. multinationals’ federal corporate income tax liabilities by $63 billion over a decade. Calculating GILTI on a country-by-country basis would raise $92 billion, more than half of which would be lost to allowing GILTI FTC carryforwards. Switching to the OECD’s tangible asset and payroll substance carve-outs instead of the current 10 percent exemption for tangible assets has a small net effect, losing a little revenue during the five years of 7.5 percent exemptions and raising a little revenue under the subsequent 5 percent exemptions. On net, bringing GILTI into compliance with Pillar 2 would raise $106 billion over a decade. Note that this modeling omits loss carryforwards, which would reduce revenue from Pillar 2 compliance.

| Change in Federal Corporate Income Tax Liabilities of U.S. MNEs from Pillar 2 Compliance, Billions of Dollars | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provision | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2031 | Total |

| 15% GILTI rate | 12.4 | 13.2 | 14.2 | 15.1 | 6.8 | 7.0 | 7.2 | 7.4 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 98.8 |

| + Remove GILTI FTC haircut | -2.8 | -3.0 | -3.2 | -3.4 | -3.6 | -3.7 | -3.8 | -3.9 | -4.0 | -4.1 | -35.7 |

| + Country-by-country GILTI | 7.2 | 7.7 | 8.3 | 8.9 | 9.2 | 9.5 | 9.8 | 10.1 | 10.3 | 10.6 | 91.7 |

| + Allow GILTI FTC carryforwards | 0.0 | -2.4 | -3.7 | -4.7 | -5.4 | -6.0 | -6.5 | -6.9 | -7.3 | -7.7 | -50.8 |

| + Use OECD QBAI/payroll exemptions | -0.4 | -0.3 | -0.3 | -0.3 | -0.2 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 2.1 |

| Total | 16.4 | 15.2 | 15.3 | 15.6 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 7.4 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 7.3 | 106.0 |

| Note: This table presents the change in federal corporate income tax liabilities of U.S. multinationals in billions of dollars for each provision. All estimates include profit shifting in response to the average tax rate differential with a semi-elasticity of 0.8. | |||||||||||

| Source: Tax Foundation’s Multinational Tax Model. | |||||||||||

Industry-Level Analysis

In addition to estimating the changes in firms’ corporate income tax liabilities, we can allocate taxes from subpart F and GILTI to the controlled foreign corporations of multinationals, insofar as they give rise to subpart F and GILTI inclusions and to FTCs. Table 6 presents the average tax rates on CFC activities by industry in 2022, calculated by combining foreign taxes, initial tax liability from subpart F, and GILTI inclusions, net of the GILTI FTC and the subpart F share of the passive FTC. The total foreign tax and the net residual U.S. tax are divided by CFC profits to obtain the average tax rates.

The first column presents the average foreign tax rates on these profits, 12.5 percent on average. All other columns present the combined foreign and residual U.S. tax rates. Under current law, the U.S. imposes a 2.9 percent residual tax of CFC profits. Under the Biden plan this residual U.S. tax would rise to 7.8 percent, resulting in a combined tax rate of 20.2 percent. The partial version of the Biden administration proposal, the GILTI fix, and Pillar 2 compliance would raise this combined tax rate similarly in 2022, to 17.6, 16.3, and 17.1 percent respectively. Note that residual tax from the GILTI fix is much smaller in later years; in 2022, the effect is just the higher GILTI rate and worldwide expense allocation, as firms would begin with no GILTI foreign taxes carried forward.

These average foreign tax rates on CFC activities demonstrate a significant tax disadvantage to U.S. ownership of activities abroad. Under current law, these combined tax rates suggest that the same activities owned by foreign companies facing no residual U.S. tax would have significantly lower tax burdens and thus be more valuable. Under current law, U.S. ownership of foreign profits incurs taxes 23 percent higher than foreign ownership. Under the Biden administration’s proposal, this would almost triple, with U.S. ownership facing 63 percent higher taxes.

| Industry | Foreign | Current law | Biden | Partial | GILTI fix | Pillar 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mining |

||||||

| Oil and gas extraction, coal mining | 34.6 | 34.4 | 36.7 | 34.8 | 34.4 | 34.6 |

| All other mining | 32.7 | 35.1 | 38.8 | 36.8 | 35.1 | 36.0 |

|

Construction |

30.0 | 31.9 | 34.5 | 33.0 | 32.1 | 32.6 |

|

Manufacturing |

||||||

| Food manufacturing | 23.8 | 25.4 | 29.9 | 27.3 | 25.6 | 26.7 |

| Beverage and tobacco products | 13.3 | 16.1 | 23.9 | 20.1 | 17.6 | 19.1 |

| Paper manufacturing | 25.3 | 26.0 | 30.8 | 28.1 | 26.0 | 27.6 |

| Petroleum and coal products manufacturing | 25.2 | 25.4 | 30.0 | 27.5 | 25.3 | 26.5 |

| Pharmaceutical and medicine manufacturing | 7.4 | 11.4 | 15.3 | 13.2 | 12.1 | 12.7 |

| Other chemical manufacturing | 20.3 | 22.6 | 28.0 | 24.6 | 22.4 | 24.4 |

| Plastics and rubber products manufacturing | 17.7 | 18.8 | 22.9 | 20.6 | 19.1 | 20.1 |

| Nonmetallic mineral product manufacturing | 20.6 | 21.8 | 32.0 | 27.5 | 21.8 | 25.4 |

| Primary metal manufacturing | 31.6 | 32.4 | 40.0 | 35.9 | 32.3 | 35.2 |

| Fabricated metal products | 22.7 | 24.4 | 28.4 | 25.9 | 24.4 | 25.6 |

| Machinery manufacturing | 29.0 | 30.7 | 35.0 | 32.1 | 31.0 | 32.1 |

| Computer and electronic product manufacturing | 4.4 | 9.6 | 18.1 | 14.2 | 11.4 | 13.0 |

| Electrical equipment, appliance and component manufacturing | 11.0 | 15.3 | 26.1 | 21.0 | 17.8 | 19.2 |

| Motor vehicles and related manufacturing | 23.5 | 24.5 | 30.4 | 27.8 | 24.5 | 27.2 |

| Other transportation equipment manufacturing | 22.5 | 25.7 | 32.2 | 28.1 | 25.3 | 27.6 |

| Other manufacturing | 18.4 | 20.7 | 24.9 | 22.6 | 21.1 | 22.0 |

|

Wholesale trade |

||||||

| Machinery, equipment, and supplies | 19.1 | 23.2 | 28.3 | 24.9 | 24.4 | 24.8 |

| Other miscellaneous durable goods | 18.8 | 22.7 | 27.9 | 24.1 | 24.2 | 24.5 |

| Drugs, chemicals, and allied products | 5.8 | 9.4 | 14.1 | 11.6 | 10.9 | 11.1 |

| Groceries and related products | 20.5 | 22.9 | 27.4 | 24.7 | 22.6 | 24.3 |

| Other miscellaneous nondurable goods | 19.5 | 21.3 | 26.8 | 24.0 | 22.3 | 23.3 |

|

Retail trade |

23.5 | 24.7 | 31.3 | 27.6 | 25.2 | 27.3 |

|

Transportation and warehousing |

22.9 | 23.5 | 30.1 | 27.0 | 23.5 | 25.7 |

|

Information |

||||||

| Publishing (except internet) | 9.6 | 13.2 | 17.5 | 14.9 | 14.3 | 14.9 |

| Motion picture and sound recording | 29.0 | 29.9 | 32.4 | 30.6 | 30.1 | 30.7 |

| Other information | 10.6 | 13.3 | 21.1 | 17.5 | 14.3 | 16.5 |

|

Finance and insurance |

||||||

| Nondepository credit intermediation | 21.3 | 23.7 | 28.6 | 25.9 | 24.4 | 25.5 |

| Securities, commodity contracts, and other financial investments | 15.5 | 17.9 | 23.1 | 20.3 | 19.1 | 19.6 |

| All other finance industries | 5.6 | 11.8 | 18.9 | 15.1 | 13.9 | 14.6 |

| Insurance and related activities | 22.0 | 23.6 | 26.5 | 24.2 | 24.6 | 24.7 |

|

Real estate and rental and leasing |

13.5 | 14.3 | 22.4 | 18.9 | 14.4 | 18.0 |

|

Professional, scientific, and technical services |

16.7 | 21.0 | 26.3 | 23.3 | 22.0 | 22.3 |

|

Management of holding companies |

7.5 | 10.1 | 13.6 | 11.7 | 11.0 | 11.2 |

|

Administrative and support and waste management and remediation |

12.8 | 14.1 | 16.9 | 15.3 | 14.7 | 15.0 |

|

Arts, entertainment, and recreation |

28.0 | 28.1 | 37.2 | 32.2 | 28.1 | 31.7 |

|

Accommodation and food services |

20.0 | 20.3 | 26.8 | 23.8 | 20.3 | 22.9 |

|

Other industries |

20.2 | 20.7 | 27.6 | 24.4 | 20.7 | 23.5 |

|

All industries |

12.5 | 15.3 | 20.3 | 17.6 | 16.3 | 17.1 |

| Note: This table presents the average tax rates on CFC profits. The first column only includes foreign taxes as a share of CFC profits. All other columns include foreign taxes and residual U.S. taxes from subpart F and GILTI inclusions net of the GILTI FTC and the share of the passive FTC attributable to subpart F income. Major industries are bolded. All estimates include no profit-shifting responses, to avoid conflating that effect on average tax rates. | ||||||

| Source: Tax Foundation’s Multinational Tax Model. | ||||||

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeNot all industries are equally affected; high-tech industries are disproportionately among those facing the highest tax hikes. The most heavily affected industry—electrical equipment, appliance and component manufacturing—would face a 10.8 percentage point tax hike on its CFC profits under the full Biden administration proposal. The computer and electronic product manufacturing industry would face an 8.5 percentage point tax hike, and information services other than publishing and recording would face a 7.8 percentage point tax hike.

However, industries not often associated with profit shifting are also among the most affected. Nonmetallic mineral product manufacturing is the second most-heavily affected industry under the Biden plan, facing a 10.1 percentage point tax hike. Real estate, rental and leasing is also heavily affected, facing an 8 percentage point tax hike. Both of these industries rely relatively heavily on tangible assets and are thus more exposed to repeal of the QBAI exemption.

Profit-Shifting Responses to International Tax Changes

The main estimates include a moderate profit-shifting response to higher U.S. taxes on foreign activity. The Biden administration has claimed that their proposal would eliminate profit-shifting incentives, but this is not the case. From Table 6, the full Biden administration proposal would raise the average tax rate on CFC activity by 4.9 percentage points, but a 28 percent corporate tax rate and repeal of the FDII deduction raise the average tax rate on U.S. activity by more than 7 percentage points. On net, this would increase profit shifting out of the U.S.

To consider the magnitude of this effect, Table 7 presents the 10-year change in federal corporate income tax liabilities of U.S. multinationals for each proposal under different profit-shifting assumptions. The first column uses purely static results, with no behavioral responses. The second column uses a semi-elasticity of 0.8 with respect to the average tax rate differential between the U.S. parent and each CFC. This is the main approach we use; the numbers in the second columns match the totals in Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5. The third column uses a larger profit-shifting response estimated by Dowd, Landefeld, and Moore.[32] Using confidential microdata on multinationals and their CFCs, they estimate separate semi-elasticities for CFCs in tax havens and in non-haven countries. For average tax rates, they estimate a semi-elasticity of 0.684 in non-haven countries and a much larger semi-elasticity of 4.16 in tax havens.[33] The last two columns present the revenue loss to profit shifting under each of these assumptions, relative to the estimates with no profit-shifting responses.

| Change in Federal Corporate Income Tax Liabilities of US MNEs, under Different Profit Shifting Assumptions, Billions of Dollars | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proposal | Change in CIT Liabilities | Loss to Profit Shifting | |||||

| Static | SE = 0.8 | SE from DLM | SE = 0.8 | SE from DLM | |||

| Biden proposal | 1394.4 | 1315.9 | 1152.6 | -78.5 | -241.8 | ||

| Partial Biden | 615.6 | 579.5 | 522.3 | -36.1 | -93.3 | ||

| GILTI fix | -2.5 | 0.0 | 11.4 | 2.5 | 13.9 | ||

| Pillar 2 | 111.3 | 106.0 | 105.5 | -5.2 | -5.8 | ||

| Note: This table presents the 10-year change in federal corporate income tax liabilities of U.S. multinationals in billions of dollars for each proposal. The first three columns present the change in these liabilities from each proposal under different profit-shifting assumptions. The static estimates use no profit-shifting response. The second column uses the moderate profit-shifting response, with a semi-elasticity of 0.8 with respect to the tax rate differential between the U.S. and each CFC. The third column uses the profit-shifting response from Dowd, Landefeld, and Moore (2018), with a semi-elasticity of 4.16 for tax havens and a semi-elasticity of 0.684 for other countries. Tax havens are identified by the Congressional Research Service. The last two columns present the revenue leakage from profit shifting, calculated by subtracting the static results. | |||||||

| Source: Tax Foundation’s Multinational Tax Model. | |||||||

The full and partial Biden proposals both increase profit shifting. This greater profit shifting reduces U.S. tax revenues, as profits shifted abroad only claim a residual U.S. tax instead of the higher tax if booked domestically. Comparing our main results with the static scenario, profit shifting reduces the domestic tax liabilities of U.S. multinationals under the Biden plan by $79 billion over a decade under the Biden administration proposal, and the U.S. loses $36 billion under the partial version of it. Using the greater tax haven responsiveness from Dowd, Landefeld, and Moore, the full Biden administration proposal loses $242 billion to profit shifting.

On he other hand, the GILTI fix reduces profit shifting. Switching to worldwide expense allocation and allowing FTC carryforwards only cut taxes for firms with binding FTC limitations, which comes from facing higher foreign tax rates. These firms facing higher foreign taxes generally engage in less profit shifting. Meanwhile, the higher GILTI rate raises taxes mostly on firms with low foreign tax rates, which are also those more likely to engage in profit shifting. On net, this proposal raises foreign taxes on firms engaging in more profit shifting and cuts taxes for those that do so less, resulting in a net decrease in profit shifting.

The effect of profit shifting on the scores for Pillar 2 compliance also show net revenue losses due to greater profit shifting, but the revenue losses are much smaller than for the full or partial versions of the Biden administration’s proposals.

Foreign Country Responses to Pillar 2

MNEs are not the only entities that respond to tax changes. Other countries could potentially respond as well by raising taxes. Because the U.S. only imposes a residual tax on CFC profits net of the FTC, an increase in foreign taxes is partially offset by a larger FTC. In response to higher foreign tax rates, U.S. multinationals would also be incentivized to reduce profits shifted to those countries.

Moreover, the OECD’s Pillar 2 proposal imposing a 15 percent country-by-country minimum tax could incentivize low-tax countries to raise their effective tax rates to collect that corporate tax revenue themselves instead of allowing a multinational’s home country to collect it. We model the exposure of the U.S. tax system to this effect by supposing that the average tax rate in each CFC observation were raised to a minimum 15 percent. Table 8 presents this effect on the federal corporate income tax liabilities of U.S. multinationals.

| Change in Federal Corporate Income Tax Liabilities of US MNEs, under Different Foreign Tax Responses, Billions of Dollars | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Proposal | Current rates | 15% minimum | Difference |

| Current law | 0.0 | -20.4 | -20.4 |

| Biden proposal | 1315.9 | 1175.2 | -140.7 |

| Partial Biden | 579.5 | 502.3 | -77.2 |

| GILTI fix | 0.0 | -62.5 | -62.5 |

| Pillar 2 | 106.0 | -43.9 | -150.0 |

| Note: This table presents the 10-year change in federal corporate income tax liabilities of U.S. multinationals in billions of dollars for each proposal. The first column uses current foreign tax rates. The second column supposes that each country-industry CFC observation faced an average tax rate of at least 15 percent. The third column presents the reduction in federal corporate tax liabilities from this effect. | |||

| Source: Tax Foundation’s Multinational Tax Model. | |||

Conceivably, the higher foreign taxes could increase or decrease U.S. tax revenues. The reduction in profit shifting increases profits booked domestically and taxes on those profits, but the higher foreign taxes assessed result in higher FTCs, reducing tax revenue. In all the scenarios above, the latter effect dominates, and the higher foreign taxes result in net decreases in U.S. tax revenue.

The exposure of U.S. tax revenue to foreign tax hikes depends on how much foreign income is included in U.S. taxable income. As more foreign income is included—such as by repealing the QBAI exemption for GILTI—a larger share of total foreign taxes is included in the FTC calculations. It also depends on how much the FTC limitation constrains the FTC. At a higher corporate income tax rate or higher GILTI rate, the limitation matters less, and so the marginal revenue offset from the FTC is larger. Because indirect expense allocation and the lack of carryforwards for GILTI foreign taxes make the limitation more important, restoring worldwide expense allocation and allowing carryforwards also increase the exposure of the U.S. to foreign tax hikes.

Interestingly, cross-crediting reduces U.S. exposure to tax hikes in low-tax countries, so proposals to reduce cross-crediting—such as country-by-country GILTI calculations and the mandatory high-tax exemption—increase U.S. exposure to the foreign tax hikes. For example, consider a U.S. firm with half its CFC income in Ireland facing a 3 percent tax rate and half facing a 27 percent tax rate in Germany. With GILTI calculated on a global basis, its average foreign tax rate is 15 percent (higher than 13.125 percent), so the FTC limitation binds; if Ireland raises its effective tax rate to 15 percent, this does not change the FTC. On the other hand, if GILTI is calculated separately by country, the credit limitation binds in Germany but not in Ireland; if Ireland raises its tax rate, the FTC also increases.

Under current law, if other countries raise their effective corporate tax rates, this would reduce U.S. corporate tax liabilities by $20 billion over a decade. Because the Biden administration’s proposals—both the actual and partial versions—capture larger shares of foreign income and tax them at higher rates, these are more heavily exposed to foreign countries raising their tax rates, losing $141 billion to this under the full Biden plan and $77 billion under the partial version. The GILTI fix and Pillar 2 compliance also significantly increase U.S. exposure to foreign tax hikes. If all other countries raise their effective tax rates to at least 15 percent, under current law the only revenue raised by GILTI comes from temporary timing effects and indirect expense allocation. Allowing FTC carryforwards essentially eliminates the tax on timing effects. If other countries raise their effective foreign tax rates to at least 15 percent in response to Pillar 2, the U.S. will lose revenue by implementing the GILTI fix or by making GILTI comply with Pillar 2.

Results for Other Options

Finally, we present a set of other options for modifying the international tax rules facing U.S. multinationals in Table 9. We group these into three categories: changes to the level of GILTI calculations and the FTC; changes to the substance exemption for GILTI; and changes to indirect expense allocation rules.

| Change in Federal Corporate Income Tax Liabilities of U.S. MNEs from Various Options, $billions, Billions of Dollars | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Policy | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2031 | Total |

|

GILTI calculation and FTC options |

|||||||||||

| Allow GILTI FTC carryforwards | 0.0 | -2.0 | -3.1 | -3.8 | -6.1 | -6.0 | -6.2 | -6.3 | -6.6 | -6.8 | -46.9 |

| Country-by-country | 4.7 | 5.0 | 5.4 | 5.7 | 8.0 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 8.7 | 8.9 | 9.1 | 72.2 |

| Country-by-country, with carryforwards | 4.7 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 27.3 |

| Mandatory high-tax exemption at 18.9% | 3.6 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 52.2 |

| Mandatory high-tax exemption at 18.9%, with carryforwards | 3.6 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 19.4 |

|

GILTI exemption options |

|||||||||||

| Remove QBAI exemption | 3.7 | 4.0 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 7.0 | 7.2 | 7.4 | 7.6 | 59.0 |

| 7.5% QBAI & payroll exemptions | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.0 |

| 5% QBAI & payroll exemptions | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 25.2 |

|

Expense allocation options |

|||||||||||

| Restore worldwide interest expense allocation | -1.8 | -1.9 | -2.1 | -2.2 | -2.4 | -2.4 | -2.5 | -2.6 | -2.6 | -2.7 | -23.3 |

| Switch to water’s edge R&D expense allocation | 1.8 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 23.1 |

| Eliminate interest expense allocation | -5.4 | -5.7 | -6.0 | -6.4 | -6.7 | -6.9 | -7.1 | -7.3 | -7.5 | -7.7 | -66.8 |

| Eliminate R&D expense allocation | -6.4 | -6.7 | -7.1 | -7.5 | -7.8 | -8.1 | -8.3 | -8.5 | -8.7 | -8.9 | -78.0 |

| Apply section 265 denial of deductions to excluded foreign income | 8.4 | 9.0 | 9.7 | 10.3 | 9.0 | 9.3 | 9.6 | 9.8 | 10.1 | 10.4 | 95.7 |

| Note: This table presents the change in federal corporate income tax liabilities of U.S. multinationals in billions of dollars for each provision. All estimates include profit shifting in response to the average tax rate differential with a semi-elasticity of 0.8. | |||||||||||

| Source: Tax Foundation’s Multinational Tax Model. | |||||||||||