Key Findings

- Many states have adopted inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. adjustments within their individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. codes to avoid unlegislated and unintended increases in taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. burdens.

- If individual income tax provisions are not adjusted for inflation, taxpayers’ burdens increase over time, with the greatest increases often concentrated among lower- and middle-income taxpayers.

- Inflation increases tax burdens both by increasing the share of taxpayers’ income that is subject to tax even if their earnings have not increased in real terms and by improperly measuring a taxpayer’s income; state inflation adjustments tend to focus on the former concern.

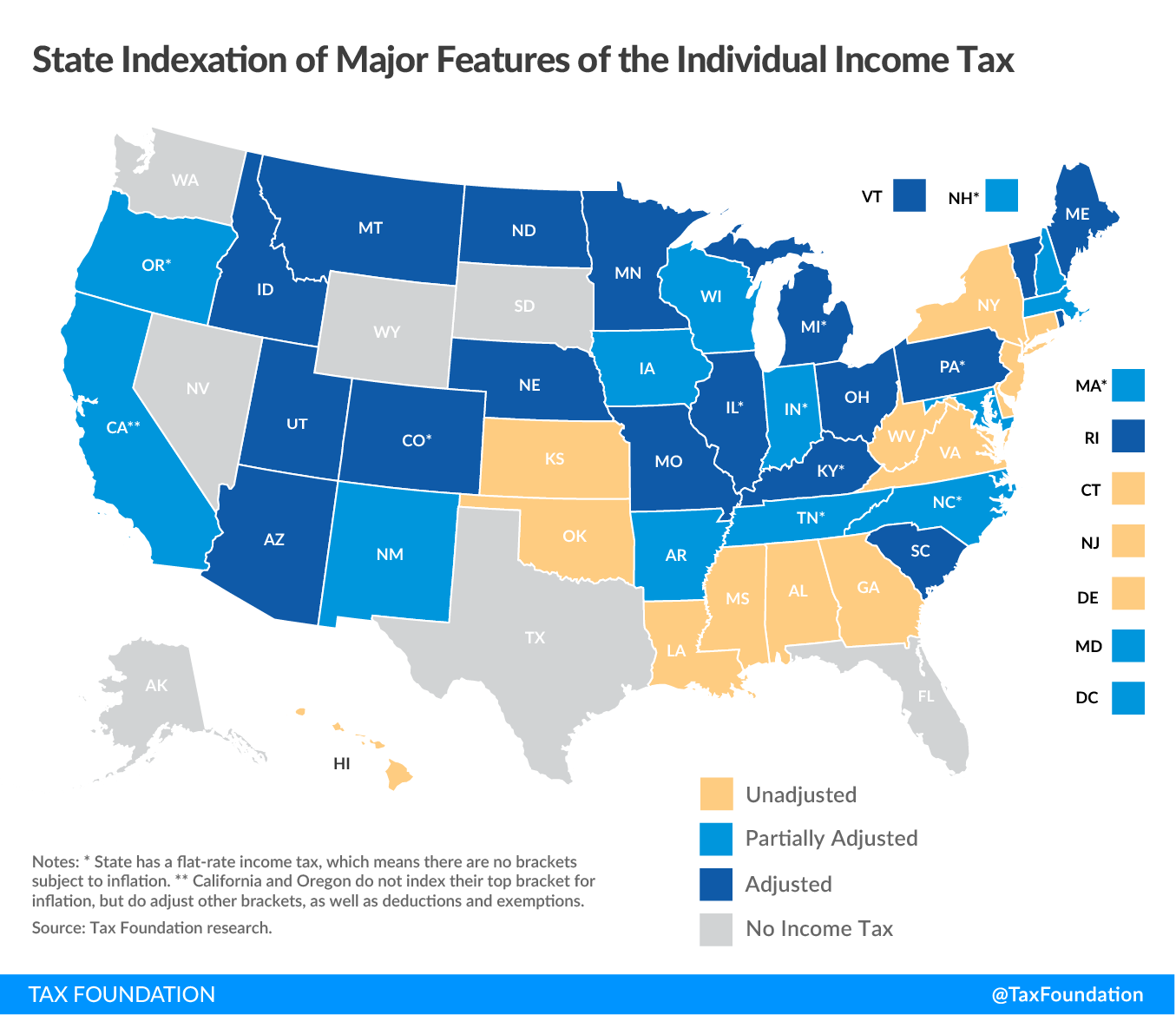

- Twenty-four states and the District of Columbia adjust at least one of the three major inflation-indexable provisions: brackets, the standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. Taxpayers who take the standard deduction cannot also itemize their deductions; it serves as an alternative. , and the personal exemption. An additional six states lack indexing provisions, but implement flat-rate income taxes that do not require inflation adjustment of bracket widths.

- States use different measures of inflation, different equations for their calculations, different rounding conventions, and even different dates for calculating inflation adjustments, and vary on whether calculations are annual or cumulative from a given base year.

- Policymakers should favor inflation adjustment mechanisms which are simple, replicable, and permit timely determinations of new tax parameters. Indexing mechanisms should also be consistent within a given state and rounding conventions should not invariably favor the government over the taxpayer.

- State officials should give serious consideration to the choice of inflation measure and whether it reflects the intended aims of the cost-of-living adjustment. Most states continue to use Traditional CPI, but Chained CPI is also used, as are localized indices and the GDP Deflator, a broader economic measure than the price indices more commonly used.

Introduction

Many states build a cost-of-living adjustment into their individual income tax brackets, standard deductions, personal exemptions, and other features of their tax codes because inflation can otherwise impose a hidden tax, with a greater share of the taxpayer’s income taxed even if their income has not increased in real terms. A movement that began with three states—Arizona, California, and Colorado—in 1978 has now expanded to half of them.

Some states index both rates (by way of bracket widths) and bases (deductions, exemptions, and other provisions); others are more selective. Inflation indexingInflation indexing refers to automatic cost-of-living adjustments built into tax provisions to keep pace with inflation. Absent these adjustments, income taxes are subject to “bracket creep” and stealth increases on taxpayers, while excise taxes are vulnerable to erosion as taxes expressed in nominal dollars, rather than rates, slowly lose value. of any sort is irrelevant for the seven states which forgo an individual income tax altogether, and there are no brackets to index in the 11 states with a single-rate income tax, though indexing provisions which define the income base, such as deductions and exemptions, still matter in these states. Not all states offer both a standard deduction and a personal exemption, though all but Pennsylvania offer at least one of the two. Among jurisdictions with a graduated-rate income tax, only 10 states offer no rate or base inflation adjustment of any kind.[1]

Indexing of income tax bracket widths applies a cost-of-living adjustment meant to prevent “bracket creepBracket creep occurs when inflation, or real income growth, pushes taxpayers into higher income tax brackets. Bracket creep results in an increase in income taxes without an increase in real income. Many tax provisions—both at the federal and state levels—are adjusted for inflation. Over time, bracket creep can increase how much income tax people owe as their income grows, either due to inflation or economic growth. To prevent inflation-driven bracket creep, many tax provisions at the federal and state levels are adjusted for inflation. ,” whereby an ever-greater share of income (in real terms) is subject to higher tax rates due to inflation. The effect is similar for deductions and exemptions, which decline in value if unadjusted. While inflation indexing is increasingly common, however, there is nothing common about the variety of ways states approach the issue.

Figure 1.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeThis paper makes the case for inflation indexing and reviews which states adjust which tax provisions, but also delves into the unique approaches states take in their mechanisms for inflation adjustments. It also suggests a few best practices to enhance simplicity, timeliness, and replicability.[2]

A Short History of Inflation Indexing

Today, inflation indexing is widely accepted as a best practice in both federal and state taxation. Less than 50 years ago, however, it was merely an idea bandied about in academic circles. The scourge of high inflation in the 1970s made what had been an intellectual argument a suddenly politically salient one. Those were the days when President Gerald Ford labeled inflation Public Enemy Number One and impressed upon the public the need to “Whip Inflation Now” (WIN). As the decade came to an end, the Consumer Price Index (CPI), a measure of purchasing power, had risen an average of 7.6 percent per year for the previous eight years, meaning that goods were becoming consistently costlier as measured in nominal dollars.[3]

Many of the proposals were not ready for primetime, and an incensed public did not much care for the notion that inflation could be tamed if only they carpooled more or wore additional layers of clothing. Some wore the resulting “WIN” buttons upside down, spelling out NIM: “No Immediate Miracles.” But in the absence of miracles, other steps could be taken. Among them: no longer allowing inflation to impose stealth tax increases.

When Milton Friedman proposed inflation indexing, he called it “the escalator.”[4] The concept stuck. The name, perhaps fortunately, did not. Arizona, California, and Colorado adopted inflation indexing measures in 1978, with Iowa, Minnesota, and Wisconsin following in 1979. Of the original six, four indexed both brackets and income modifications (deductions, exemptions, and credits). Initially, Arizona did not adjust bracket widths, though it adopted this provision within a few years, and Iowa adjusted brackets but few other features of its tax code.[5] At the federal level, inflation indexing featured in the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981, taking effect in 1985 following three years of phased-in rate reductions.[6]

Today, 17 of the 32 states with graduated-rate income taxes adjust brackets for inflation. Of the 31 states which offer a standard deduction, 20 and the District of Columbia make a cost-of-living adjustment, and the personal exemption is inflation-indexed in 12 of the 32 states offering it. Because the standard deduction is indexed at the federal level (as was the personal exemption prior to its suspension under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017), states which conform to the federal standard deduction automatically implement the federal government’s inflation-indexing measures, while indexing of brackets is something states must do on their own.

|

(a) California and Oregon do not fully index their top brackets. (b) New Hampshire and Tennessee tax interest and dividend income only. Sources: State statutes; Tax Foundation research |

|||

| State | Brackets | Standard Deduction | Personal Exemption |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | — | — | — |

| Alaska |

No Income Tax |

||

| Arizona | Indexed | Indexed | Indexed |

| Arkansas | Indexed | — | Indexed |

| California | Indexed (a) | Indexed | Indexed |

| Colorado | Flat Tax | Conforms to Federal | n/a |

| Connecticut | — | n/a | — |

| Delaware | — | — | — |

| Florida |

No Income Tax |

||

| Georgia | — | — | — |

| Hawaii | — | — | — |

| Idaho | Indexed | Conforms to Federal | n/a |

| Illinois | Flat Tax | n/a | Indexed |

| Indiana | Flat Tax | n/a | — |

| Iowa | Indexed | Indexed | — |

| Kansas | — | — | — |

| Kentucky | Flat Tax | Indexed | n/a |

| Louisiana | — | n/a | — |

| Maine | Indexed | Conforms to Federal | n/a |

| Maryland | — | Indexed | — |

| Massachusetts | Flat Tax | n/a | — |

| Michigan | Flat Tax | n/a | Indexed |

| Minnesota | Indexed | Conforms to Federal | Indexed |

| Mississippi | — | — | — |

| Missouri | Indexed | Conforms to Federal | n/a |

| Montana | Indexed | Indexed | Indexed |

| Nebraska | Indexed | Indexed | Indexed |

| Nevada |

No Income Tax |

||

| New Hampshire | Flat Tax (b) | n/a | — |

| New Jersey | — | n/a | — |

| New Mexico | — | Conforms to Federal | n/a |

| New York | — | — | n/a |

| North Carolina | Flat Tax | — | n/a |

| North Dakota | Indexed | Conforms to Federal | n/a |

| Ohio | Indexed | n/a | Indexed |

| Oklahoma | — | — | — |

| Oregon | Indexed (a) | Indexed | Indexed |

| Pennsylvania | Flat Tax | n/a | n/a |

| Rhode Island | Indexed | Indexed | Indexed |

| South Carolina | Indexed | Conforms to Federal | Indexed |

| South Dakota |

No Income Tax |

||

| Tennessee | Flat Tax (b) | n/a | — |

| Texas |

No Income Tax |

||

| Utah | Flat Tax | Percentage of Federal | n/a |

| Vermont | Indexed | Indexed | Indexed |

| Virginia | — | — | — |

| Washington |

No Income Tax |

||

| West Virginia | — | n/a | — |

| Wisconsin | Indexed | Indexed | — |

| Wyoming |

No Income Tax |

||

| District of Columbia | — | Indexed | n/a |

Why Inflation Indexing Matters

Inflation increases tax burdens in two distinct ways: first, by increasing the share of a taxpayer’s income that is subject to tax even if their earnings have not increased in real terms, and second, by improperly measuring a taxpayer’s income. States’ indexing measures have generally focused on the first impact and not the second, though an optimal tax code would address both.

The quintessential example of the first mismeasurement is “bracket creep,” though the concept is equally applicable to base provisions like the standard deduction or personal exemption. Imagine a simple tax schedule in which a rate of 3 percent is levied on the first $10,000 in income, a rate of 4 percent on the next $10,000, and so on up to 7 percent on income above $40,000. Suppose, now, that these brackets were adopted 50 years ago, in January 1969, and consider a taxpayer with $50,000 in today’s (January 2019) dollars. If we hold that income constant in real terms across the years, the effective rate increases by two-thirds over the half-century even as actual rates and brackets remain constant, because the brackets fail to adjust with inflation.

|

Source: Tax Foundation calculations. |

||||||

| 1969 | 1979 | 1989 | 1999 | 2009 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxable Income (2019 $) | $50,000 | $50,000 | $50,000 | $50,000 | $50,000 | $50,000 |

| Nominal Taxable Income | $7,072 | $13,567 | $24,055 | $32,637 | $41,941 | $50,000 |

| Nominal Tax Burden | $212.16 | $442.68 | $902.75 | $1,358.22 | $1,935.87 | $2,500 |

| Effective Tax Rate | 3.0% | 3.3% | 3.8% | 4.2% | 4.6% | 5.0% |

In 1969, all our hypothetical earner’s income is subject to the 3 percent bracket. By 1989, his income is spread across three brackets. By 2009, the taxpayer has income in all five tax bracketsA tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. , even though, in real terms, his income has not increased. His effective rate has risen from 3 to 5 percent, and his top marginal rate from 3 to 7 percent.

When Alabama adopted its graduated rate income taxA graduated rate income tax system consists of tax brackets where tax rates increase as income increases. Typically, this results in a taxpayer’s effective income tax rate, or the percentage of their income paid in taxes, increasing as their income increases. in 1935, the majority of taxpayers were exempted altogether, and few taxpayers were subject to the top marginal rate of 5 percent,[7] imposed upon income above $3,000—about $55,000 in today’s dollars. Today, wage earners have the bulk of their income taxed at the top rate. Absent inflation indexing, the nature of a tax changes dramatically.

Meanwhile, capital gains are an example of how inflation can impact definitions of income. Consider a purchase of $10,000 worth of shares in 1998, sold for $20,000 in 2018. Both the federal and state government would treat this as capital gains income of $10,000. The federal government provides a preferential rate, while most states do not. In real terms, however, the gain is far less than $10,000 because cumulative inflation during that period was just over 54 percent, making the real gain $4,595.

If someone invested in a Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) index fund that year, cashing out in 2018, their return would have been an impressive 190 percent. Adjusting for inflation, the gain is 88 percent—still good, but ideally not taxable as if the return were more than twice as much.

In an ideal world, income tax systems would include the inflation-adjustment of capital gains income as well as tax brackets, deductions, and exemptions. In practice this can be difficult, since adjusting capital gains for inflation without situating that change in broader adjustments to the tax code can create opportunities for tax arbitrage. In the absence of an inflation adjustment for capital gains, lower rates can help compensate, if imprecisely.

It is important to note here that the above inflation adjustments all use the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U), the most popular measure of inflation in the United States, and the one most commonly used by states in their own inflation adjustments. It is not, however, the only available inflation measure, or necessarily even the best one for these purposes. Alternatives are discussed briefly later in this paper.

The economic incidence of inflation-linked tax increases depends on the structure of a given state’s tax code. For instance, if large deductions and exemptions are primary levers of progressivity, or if there is significant rate progressivity within middle-income ranges, the additional tax costs due to inflation will be concentrated on lower- and middle-income taxpayers. Inflation indexing will be more significant for higher earners to the degree that high levels of progressivity continue into higher income strata, but there always exists a top bracket above which all income is taxed at a given rate. Thus, inflation indexing is inherently more significant for those who have all, or a greater proportion of, their income taxed below the top rate than it is for those who have much of their income subject to that highest rate.[8]

Indexing has important implications for tax equity, political accountability, and the rate of growth of government revenues. Absent indexation, inflation creates distortions in tax liability because the changes do not affect all taxpayers equally, or in line with legislative intentions. If no changes are made to state tax provisions, moreover, inflation increases state tax collections significantly faster than the growth of state income (in real terms). The tax code changes without a vote being taken, yielding a lack of political accountability.

Even with indexation, state tax receipts will often grow faster than state income. Under a progressive system, those whose earnings increase in real terms will face higher effective (as well as top marginal) rates. Inflation indexing does not prevent this, nor is it intended to; only a flat taxAn income tax is referred to as a “flat tax” when all taxable income is subject to the same tax rate, regardless of income level or assets. will. It does, however, ensure that tax liability as a percentage of income does not increase due to inflation, with a taxpayer facing greater tax burdens on income with the same purchasing power.[9]

Inflation Adjustment Mechanisms

States use different measures of inflation, different equations for their calculations, different rounding conventions, and even different dates for calculating a given year’s inflation adjustment. Some states make cumulative adjustments from a base year, while others upwardly revise the figures from the prior year’s brackets. Some use fiscal years, others calendar years, and others their own state-defined periods, while many follow the federal convention of a 12-month period running from September to August.

The advantage of using something other than a calendar year is that enables an earlier announcement of the inflation adjustment, to the benefit of those filing estimated returns. It may also allow time for any revisions and corrections from the data source, either the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) or the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).

Choice of inflation measure is significant as well. Under the TCJA, the federal government switched from CPI to Chained CPI. Traditional CPI is based on the change in price of a basket of goods determined by spending patterns at some point in the past and is thus susceptible to substitution bias. If pork prices rise but the prices of chicken, turkey, and beef fall, consumption of each of those meats is likely to rise as people purchase less pork and more substitutionary goods. By contrast, if the real cost of all meat—or worse, all food—rose, this would have a much larger impact on people’s pocketbooks.

The availability of substitutes does not imply the absence of inflation (if high inflation means that people who used to be able to afford steaks must now settle for hamburgers and hot dogs, there has been a clear change in cost of living), but an unchanging basket of goods is necessarily somewhat arbitrary in its measurement of changes of purchasing power, and can overstate the true cost of living.[10] Chained CPI, a newer measure, is intended to account for substitution effects by developing market baskets for each period and “chaining” them to each other.[11]

Over a sufficiently long time-scale, Chained CPI is likely the more accurate measure, but values within Chained CPI continue to be revised for several years, making it an imperfect basis for year-to-year adjustments.[12] Furthermore, it may underestimate cost of living increases for fixed-income populations, whose consumption often faces higher inflation, and on the whole, is more likely to err in favor of the government and not the taxpayer, as contrasted with the more generous traditional CPI measure.[13]

Both CPI and Chained CPI, moreover, are price indices, based on consumption. However, overall purchasing power includes the cost of consumption and investment, and CPI measures do not capture the change in the price of investments. For indexing many benefit programs, consumption is what matters, but if trying to approximate real income (which may be spent or saved) for income tax purposes, a broader measure may be appropriate. Two states use the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) implicit deflator in lieu of CPI. This broader macroeconomic measure considers price changes for consumers, business, government, and foreigners (and not just purchases by U.S. urban consumers).

Finally, whatever the choice of inflation measure, calculation parameters vary. Some approaches are models of simplicity, while others are intricate to the point of unwieldiness. Iowa, for instance, adopts an approach that would be surprisingly difficult to recalculate, as its factors include decades of calculations based on uncorrected annual figures.

The following table provides a general overview of approaches, with a focus on states which adjust brackets for inflation. The approach of each state which adjusts any of the three commonly indexed tax features (brackets, standard deduction, and personal exemption) is briefly detailed later in this paper. (Generally, states use the same adjustment mechanisms for rate and base provisions, but not always.) The variation is considerable.

|

(a) In Iowa, the two inflation factors against which tax tables are multiplied are themselves rounded, though there is not a separate rounding convention for the resulting dollar amounts, which thus defaults to the nearest dollar. (b) Minnesota does not currently conform to a post-TCJA version of the Internal Revenue Code but draws its inflation adjustment statute to IRC § 1(f). When the state’s conformity date is updated, Minnesota’s inflation measure will switch to Chained CPI unless lawmakers expressly disclaim the change. (c) Adopts inflation measure specified by IRC § 1(f). Sources: state statutes; Tax Foundation research. |

|||

| State | Time Period | Inflation Measure | Rounding Convention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona | Annual | Metro Phoenix CPI | Nearest $1 |

| Arkansas | Annual | Traditional CPI | Nearest $100 |

| California | Annual | California CPI | Nearest $1 |

| Idaho | Cumulative | Traditional CPI | Nearest $1 |

| Iowa | Cumulative | GDP Deflator | Nearest 0.1% Factor (a) |

| Maine | Annual | Chained CPI | Nearest $1 |

| Minnesota | Cumulative | Traditional CPI (b) | Nearest $10 |

| Missouri | Cumulative | Traditional CPI | Nearest $1 |

| Montana | Cumulative | Traditional CPI | Nearest $100 |

| Nebraska | Cumulative | Traditional CPI | Nearest $10 |

| North Dakota | Annual | Chained CPI (c) | Next Lowest $50 |

| Ohio | Annual | GDP Deflator | Nearest $50 |

| Oregon | Cumulative | Traditional CPI | Next Lowest $50 |

| Rhode Island | Cumulative | Traditional CPI | Next Lowest $50 |

| South Carolina | Cumulative | Chained CPI | Nearest $10 |

| Vermont | Cumulative | Traditional CPI | Next Lowest $50 |

| Wisconsin | Cumulative | Traditional CPI | Nearest $10 |

Design Considerations

There is not necessarily a “correct” way to conduct inflation adjustments, but there are certainly considerations which should be taken into account in their design. As a state-by-state review (found later in this paper) reveals, methodological variations arise not only state-to-state but even provision-to-provision within a given state, with the same state sometimes having different mechanisms for adjusting the standard deduction or personal exemption than they do for the tax brackets. Under some systems, inflation-adjusted brackets can be known in advance, while under other tax regimes, values may be uncertain until the tax year is near its close. Some are easily replicable, while others rely on obscure inputs. States even differ in the basis of their adjustments, using different measures of inflation.

There may not be a single approach which is clearly optimal, but some are clearly suboptimal. Considerations for policymakers in the design of inflation indexing provisions follow.

Systems which permit earlier determinations should be favored. States often take the view that inflation-adjusted brackets are not necessary until the latter half of the tax year, but the uncertainty this creates comes at a cost. It undermines the accuracy of withholding and quarterly estimated returns, and it fails to give taxpayers a clear picture of the tax system under which they live. States create uncertainty and undermine transparency when they adopt approaches which do not allow a cost-of-living adjustment to be calculated until well into the tax year it is intended to address.

The federal government’s chosen 12-month period, from September to August, enables the new brackets to be set before the start of the tax year. States would do well to follow a similar convention. Under the federal approach, for instance, the inflation factor for tax year 2019 would be determined by the cost of living increase between two 12-month periods, (1) September 2016 to August 2017 and (2) September 2017 to August 2018. Since monthly data through August 2018 are available prior to January 2019, there is no delay in promulgating the new tax tables.

Calculations should be simple and easily replicable. Both annual and cumulative adjustments are easy to replicate if well designed. A cumulative cost-of-living adjustment from an established base year to the present (or some recent date) under an established inflation measure presents no difficulties, nor does adjustment of the prior year’s tax tables based on one year of inflation. Standing in contrast to these approaches is a system like Iowa’s, where the equation involves the product of all inflation adjustments for every year from the base year to present, in their original uncorrected form. To replicate the calculation produced by the Iowa Department of Revenue, someone would not only need to input each year’s inflation adjustment factor separately but would also be required to obtain contemporaneous documents to determine what that factor was in the preliminary uncorrected release.

Indexing mechanisms should be consistent within a given state. States frequently impose inflation adjustment by degrees—first adjusting the brackets, then coming back a few years later and indexing deductions and exemptions as well, or vice versa. Consequently, the mechanisms chosen for inflation adjustments are sometimes inconsistent even within a particular state, with different base years or other discrepancies emerging. This is needlessly complex, and can give rise to mistakes when legislators, tax preparers, or others try to anticipate adjustments. To the extent possible, these provisions should be harmonized, with the statutory amounts revised as necessary to allow the use of a consistent base year.

Rounding conventions also vary. States which round to the nearest $100 for tax tables cannot easily adopt the same expedient for adjusting a personal exemption credit with a value in the double or low triple digits. While different rounding conventions are less of a concern, this issue can be avoided by rounding all tax features to the nearest dollar, if desired. Here, states must weigh this consistency against whatever simplification benefits there may be in presenting taxpayers with more intuitive brackets.

Rounding conventions should not invariably favor the government over the taxpayer. Some states prioritize a truly neutral inflation adjustment, rounding brackets to the nearest dollar. Others favor the perceived simplicity or symmetry of rounding to a multiple of $10, $50, or $100. In some cases, however, states adopt the federal convention of always rounding down, such that a cost-of-living adjustment that yielded a bracket range beginning with $11,997 would be simplified to $11,950, not $12,000. Especially if adjustments are made to each successive year’s tax tables, and not cumulatively, this can yield significant errors in the government’s favor over time.

Less aggressive rounding conventions are preferable. There is no compelling reason why it is necessary to use the nearest $50 or $100. To the extent that rounding occurs, though, it should not structurally favor the government over the taxpayer, and should round to the nearest established multiple, not the next lowest.

Inflation measures should be chosen with care. Most states utilize the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U), though several states follow the federal government, which switched to the Chained Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (C-CPI-U) under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. Whereas CPI tracks the fluctuation in prices for a given basket of goods, Chained CPI allows for certain substitutions in that market basket over time. Arguably Chained CPI is more subjective in one respect, inasmuch as the goods with tracked prices are not directly comparable over time, but what C-CPI loses in that form of consistency it gains in its reflection of people’s actual consumption. A product may increase in price not because of inflation but because demand has spiked or, conversely, that it has been replaced by an alternative product for most users, with implications for price competition for those who still demand the old good.

States should, however, strive for consistency. Excise taxes, particularly motor fuel taxes, are often indexed for inflation. There is a question of equity when the measure of inflation chosen for upward tax adjustments is more generous than the one chosen to avoid unlegislated tax increases.

Localized measures, based on state or metropolitan area, have the advantage of being more precisely tailored to changes in the cost of living for affected taxpayers, but the smaller dataset may yield greater fluctuations. Finally, the GDP Deflator may be preferable to all price indices, as it measures changes in the broader economy, and not just consumption. The adjustment is, after all, made to income taxes, not consumption taxes, and should reflect all uses of income, not just spending.

State-by-State Review

Each state has its own approach to inflation indexing. Sometimes the differences are subtle, other times dramatic. The remainder of this paper is devoted to a state-by-state statutory review of these provisions. An appendix provides statutory citations for the provisions in each state.

Arizona

Alone among states, Arizona uses CPI as calculated for a metropolitan statistical area (MSA), in this case the Metro Phoenix MSA. Tax tables are adjusted year-over-year based on the average annual change between Metro Phoenix CPI between the prior two complete calendar years. For instance, the annual increase between calendar years 2017 and 2018 would determine the adjustment factor for 2019 taxes. Rounding is to the nearest dollar, and in the event of deflation, the bracket kick-ins are not allowed to decline.

For each taxable year beginning from and after December 31, 2015, the department shall adjust the income dollar amounts for each rate bracket prescribed by subsection A, paragraph 5 of this section according to the average annual change in the metropolitan Phoenix consumer price index published by the United States bureau of labor statistics. The revised dollar amounts shall be raised to the nearest whole dollar. The income dollar amounts for each rate bracket may not be revised below the amounts prescribed in the prior taxable year.[14]

The same approaches and rounding conventions are used for inflation-adjusting the standard deduction[15] and personal exemption.[16]

Arkansas

Arkansas is one of two states—along with South Carolina—to impose a cap on inflation adjustments, limiting them to no more than a 3 percent annual increase. As measured by CPI, annual inflation rates have only exceeded Arkansas’s 3 percent cap five times in the past two decades (in 2000, 2005, 2006, 2008, and 2011, with the highest being 3.8 percent in 2008), whereas higher rates of inflation used to be considerably more common. (The annual inflation rate was above 3 percent all but one year between 1967 and 1993.)[17] The state’s inflation measure is calculated as the percentage by which CPI for the most recent 12-month September-to-August period exceeds that of the preceding 12-month period and is rounded to the nearest $100.

(1) The Director of the Department of Finance and Administration shall prescribe annually a table which shall apply in lieu of the table contained in subsection (a) of this section with respect to each succeeding taxable year. The director shall increase the minimum and maximum dollar amounts for each rate bracket, rounding to the nearest one hundred dollars ($100), for which a tax is imposed under the table by the cost-of-living adjustment for each calendar year and by not changing the rate applicable to any rate bracket as adjusted.

(2) For purposes of subdivision (d)(1) of this section, the cost-of-living adjustment for a calendar year is the percentage, if any, by which the CPI for the current calendar year exceeds the CPI for the preceding calendar year, not to exceed three percent (3%). The CPI for any calendar year is the average of the Consumer Price Index as of the close of the twelve-month period ending on August 31 of such calendar year. “Consumer Price Index” means the last Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers published by the United States Department of Labor.

(3) The new tables, as adjusted annually, shall be used by the director in preparing the income tax withholdingWithholding is the income an employer takes out of an employee’s paycheck and remits to the federal, state, and/or local government. It is calculated based on the amount of income earned, the taxpayer’s filing status, the number of allowances claimed, and any additional amount the employee requests. tables pursuant to § 26-51-907.[18]

The state’s personal exemption credit is also indexed, using a 2001 base year with rounding to the nearest dollar. The personal exemption only increases if year-over-year general revenues rise at least 4.2 percent and exceeded forecast by at least 0.5 percent or net available revenues exceeded the total distributions under the state’s Revenue Stabilization Law.[19]

California

It is impossible to calculate California’s cost of living adjustment prior to the start of the tax year, or even in its early months, as the state uses an annual adjustment predicated on the percentage increase between June of the prior calendar year and June of the current calendar year. This had the advantage of using current figures, but the disadvantage of not being available until the latter half of the tax year. The state uses California CPI as its inflation measure and applies the adjustment to the prior year’s tax table, rounded to the nearest dollar.

For each taxable year beginning on or after January 1, 1988, the Franchise Tax Board shall recompute the income tax brackets prescribed in subdivisions (a) and (c). That computation shall be made as follows:

(1) The California Department of Industrial Relations shall transmit annually to the Franchise Tax Board the percentage change in the California Consumer Price Index for all items from June of the prior calendar year to June of the current calendar year, no later than August 1 of the current calendar year.

(2) The Franchise Tax Board shall do both of the following:

(A) Compute an inflation adjustment factor by adding 100 percent to the percentage change figure that is furnished pursuant to paragraph (1) and dividing the result by 100.

(B) Multiply the preceding taxable year income tax brackets by the inflation adjustment factor determined in subparagraph (A) and round off the resulting products to the nearest one dollar ($1).[20]

California uses the same inflation adjustment conventions for its standard deduction[21] and personal exemption.[22]

Colorado

Colorado has a flat tax with an income starting point of federal taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. Taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. with relatively few adjustments, which brings in the federal inflation-adjusted standard deduction and, before it was (temporarily) zeroed out by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the similarly-adjusted personal exemption. Because Colorado’s code automatically incorporates the federal approach, it uses a cumulative Chained CPI system.[23]

Idaho

Idaho adjusts cumulatively from a 1998 base year and uses calendar years as the basis of its calculation. The inflation factor applied to the statutory tax rates is CPI for the immediately preceding calendar year (for instance, 2018 for the 2019 tax year) divided by CPI for calendar year 1998. No rounding convention is specified, so figures are rounded to the nearest dollar. The state’s standard deduction conforms to the federal deduction, which is itself indexed for inflation under Chained CPI.

For taxable year 2000 and each year thereafter, the state tax commission shall prescribe a factor which shall be used to compute the Idaho income tax brackets provided in subsection (a) of this section. The factor shall provide an adjustment to the Idaho tax brackets so that inflation will not result in a tax increase. The Idaho tax brackets shall be adjusted as follows: multiply the bracket amounts by the percentage (the consumer price index for the calendar year immediately preceding the calendar year to which the adjusted brackets will apply divided by the consumer price index for calendar year 1998). For the purpose of this computation, the consumer price index for any calendar year is the average of the consumer price index as of the close of the twelve (12) month period for the immediately preceding calendar year, without regard to any subsequent adjustments, as adopted by the state tax commission. This adoption shall be exempt from the provisions of chapter 52, title 67, Idaho Code. The consumer price index shall mean the consumer price index for all U.S. urban consumers published by the United States department of labor. The state tax commission shall annually include the factor as provided in this subsection to multiply against Idaho taxable income in the brackets above to arrive at that year’s Idaho taxable income for tax bracket purposes.[24]

Illinois

Because Illinois has a single-rate tax, there are no brackets to index for inflation, and the state forgoes a standard deduction. It does, however, adjust its personal exemption for inflation, using a September-to-August year and making a cumulative CPI adjustment from calendar year 2011 to the year preceding the current tax year. Rounding is to the next lowest multiple of $25.

Cost-of-living adjustment. For purposes of item (5) of subsection (b), the cost-of-living adjustment for any calendar year and for taxable years ending prior to the end of the subsequent calendar year is equal to $2,050 times the percentage (if any) by which:

(1) the Consumer Price Index for the preceding calendar year, exceeds

(2) the Consumer Price Index for the calendar year 2011.

The Consumer Price Index for any calendar year is the average of the Consumer Price Index as of the close of the 12-month period ending on August 31 of that calendar year.

The term “Consumer Price Index” means the last Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers published by the United States Department of Labor or any successor agency.

If any cost-of-living adjustment is not a multiple of $25, that adjustment shall be rounded to the next lowest multiple of $25.[25]

Illinois voters will soon decide whether to amend the state constitution to permit a graduated rate income tax. Inflation indexing measures are notably lacking in current proposals for the subsequent rate structure.[26]

Iowa

Iowa’s approach to inflation indexing is almost certainly the nation’s most complex, and the least susceptible to outside replication. It is also one of only two states, along with Ohio, to use the GDP Deflator rather than some variation of the Consumer Price Index for inflation purposes. The GDP Deflator differs from CPI measures inasmuch as it only includes domestic (and not imported) goods, but of those, is intended to measure the prices of all goods and services, and not just those purchased by final consumers.

There is nothing inherently complex about using the GDP Deflator, but Iowa creates complexity through its equation, since it uses an inherently annual measure for a cumulative calculation. By contrast, CPI is a base year index that enables simple comparisons between any two given years. To cope with this limitation, Iowa’s inflation adjustment statute requires a series of calculations.

First, the annual inflation factor is ascertained for the fiscal year ending prior to the tax year for which the adjustment is to be made. (Hence, 2019 tax tables would use Fiscal Year 2018, which ended June 30, 2018, as the basis for its annual inflation factor. The annual percent change cannot be negative, meaning that the inflation factor cannot be less than 100 percent.) Next, it is incorporated into a cumulative inflation factor, which is the product of the annual inflation factor for the 1988 tax year and all subsequent tax years, except that the 1988 inflation factor is set at 100 percent, as it serves as the base year.

Both the annual and cumulative inflation factors are rounded to the nearest one-tenth of one percent, and the annual factors must be those released at specific points in time—not any adjusted forms that may exist now. This makes it remarkably difficult for outside observers to reproduce or anticipate the Iowa Department of Revenue’s determinations. Under legislation adopted in 2018, these provisions will be revised subject to the contingent enactment of new statutory language in coming years, though while the base year changes, the basic approach does not.[27] The same approach is used for both brackets and the state’s standard deduction, except that the deduction is rounded to the nearest $10.[28]

-

“Annual inflation factor” means an index, expressed as a percentage, determined by the department by October 15 of the calendar year preceding the calendar year for which the factor is determined, which reflects the purchasing power of the dollar as a result of inflation during the fiscal year ending in the calendar year preceding the calendar year for which the factor is determined. In determining the annual inflation factor, the department shall use the annual percent change, but not less than zero percent, in the gross domestic product price deflator computed for the second quarter of the calendar year by the bureau of economic analysis of the United States department of commerce and shall add all of that percent change to one hundred percent. The annual inflation factor and the cumulative inflation factor shall each be expressed as a percentage rounded to the nearest one-tenth of one percent. The annual inflation factor shall not be less than one hundred percent.

-

“Cumulative inflation factor” means the product of the annual inflation factor for the 1988 calendar year and all annual inflation factors for subsequent calendar years as determined pursuant to this subsection. The cumulative inflation factor applies to all tax years beginning on or after January 1 of the calendar year for which the latest annual inflation factor has been determined.[29]

Kentucky

In 2018, Kentucky scrapped its graduated-rate individual income tax system for a 5 percent single-rate tax, obviating any need for indexation of its rate tables. The state also repealed its personal exemption credits, leaving only the standard deduction among commonly-adjusted tax provisions. The state uses an annual adjustment, multiplying the prior year’s standard deduction by the increase in CPI between the 12-month period ending July of the prior tax year and that same period ending the previous year.

(a) For taxable years beginning after December 31, 2000, and each taxable year thereafter, the standard deduction for the current taxable year shall be equal to the standard deduction for the prior taxable year multiplied by the greater of:

- The average of the monthly CPI-U figures for the twelve (12) consecutive months ending in and including the July six (6) months prior to the January beginning the current tax year, divided by the average of the monthly CPI-U figures for the twelve (12) months ending in and including the July eighteen (18) months prior to the January beginning the current tax year; or

- One (1).

(b) As used in this subsection, a tax year shall be the twelve (12) month period beginning in January and ending in December.

(c) As used in this subsection, “CPI-U” means the nonseasonally adjusted United States city average of the Consumer Price Index for all urban consumers for all items, as released by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics.[30]

Maine

Maine is one of three states to used Chained CPI, and the only state to adopt it prior to the federal government’s shift to Chained CPI as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Many economists believe that “primary” CPI overestimates cost-of-living increases because it fails to take substitution effects into account. Chained CPI is, therefore, a more constrained measure, and inflation adjustments using Chained CPI are smaller than those using primary CPI.

Both measures rely on a basket of goods and services, but whereas CPI measures the prices of the same products across time,[31] Chained CPI tries to discern how consumers’ purchasing patterns have changed, and then takes the average of the measure of inflation for the initial basket and the one reflecting changing consumption. If, for instance, the price of nectarines rose sharply, consumers might buy more plums instead, while their grocery bill remains the same. It is possible this represents a loss to consumers—maybe they would have preferred nectarines—but under Chained CPI, it contributes less to the rate of inflation.[32]

In Maine, then, inflation is determined by dividing Chained CPI for the most recently completed fiscal year (for tax year 2019 adjustments, Fiscal Year 2018 would be used) by Chained CPI for Fiscal Year 2015. In an added twist, however, the threshold for the highest bracket in the tax table uses a Fiscal Year 2016 base year rather than 2015. Rounding is to the nearest dollar.

-

Individual income tax rate tables. For the tax rate tables in section 5111:

-

Beginning in 2016 and each year thereafter, by the lowest dollar amounts of the tax rate tables specified in section 5111, subsections 1-F, 2-F and 3-F, except that for the purposes of this paragraph, notwithstanding section 5402, subsection 1-B, the “cost-of-living adjustment” is the Chained Consumer Price Index for the 12-month period ending June 30th of the preceding calendar year divided by the Chained Consumer Price Index for the 12-month period ending June 30, 2015; and

-

Beginning in 2017 and each year thereafter, by the highest taxable income dollar amount of each tax rate table, except that for the purposes of this paragraph, notwithstanding section 5402, subsection 1-B, the “cost-of-living adjustment” is the Chained Consumer Price Index for the 12-month period ending June 30th of the preceding calendar year divided by the Chained Consumer Price Index for the 12-month period ending June 30, 2016[.][33]

Maryland

In Maryland, the standard deduction is inflation-adjusted, a new provision as of 2019, but tax tables and the personal exemption are not. The state follows the federal approach (using Chained CPI), including in the rounding convention (next lowest multiple of $50), but substitutes a base year of 2017.[34]

(1) For each taxable year beginning after December 31, 2018, each minimum and maximum standard deduction limitation amount specified in subsection (c) of this section shall be increased by an amount equal to the product of multiplying the minimum and maximum standard deduction limitation amount by the cost-of-living adjustment specified in this subsection.

(2) For purposes of this subsection, the cost-of-living adjustment is the cost-of-living adjustment within the meaning of § 1(f)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code for the calendar year in which a taxable year begins, as determined by the Comptroller, by substituting “calendar year 2017” for “calendar year 2016” in § 1(f)(3)(A) of the Internal Revenue Code.

(3) If any increase determined under paragraph (1) of this subsection is not a multiple of $50, the increase shall be rounded down to the next lowest multiple of $50.

Michigan

Another state with a flat tax, Michigan has no brackets to index—and, for that matter, no standard deduction at all—but state statutes do adjust the personal exemption for inflation. The adjustment is made using fiscal years (July to June), multiplying the exemption as established for tax year 2012 by the increase in CPI from fiscal year 2011 to the most recently completed fiscal year. The exemption is rounded to the nearest $100.

For each tax year beginning on and after January 1, 2013, the personal exemption allowed under subsection (2) shall be adjusted by multiplying the exemption for the tax year beginning in 2012 by a fraction, the numerator of which is the United States Consumer Price Index for the state fiscal year ending in the tax year prior to the tax year for which the adjustment is being made and the denominator of which is the United States Consumer Price Index for the 2010-2011 state fiscal year. For the 2022 tax year and each tax year after 2022, the adjusted amount determined under this subsection shall be increased by an additional $600.00. The resultant product shall be rounded to the nearest $100.00 increment. For each tax year, the exemptions allowed under subsection (3) shall be adjusted by multiplying the exemption amount under subsection (3) for the tax year by a fraction, the numerator of which is the United States Consumer Price Index for the state fiscal year ending the tax year prior to the tax year for which the adjustment is being made and the denominator of which is the United States Consumer Price Index for the 1998-1999 state fiscal year. The resultant product shall be rounded to the nearest $100.00 increment.[35]

Minnesota

In Minnesota, the inflation indexing statute was rewritten as part of the state’s somewhat belated conformity with the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2019. The state now uses the change in Chained CPI from the 12-month period ending August 2019 to the 12-month period ending August of the preceding calendar year. Rounding is to the nearest $10.

(f) The commissioner shall adjust the maximum subtraction and threshold amounts in paragraphs (b) to (d) as provided in section 270C.22. The statutory year is taxable year 2019. The maximum subtraction and threshold amounts as adjusted must be rounded to the nearest $10 amount. If the amount ends in $5, the amount is rounded up to the nearest $10 amount.

[…] (a) The commissioner shall annually make a cost of living adjustment to the dollar amounts noted in sections that reference this section. The commissioner shall adjust the amounts based on the index as provided in this section. For purposes of this section, “index” means the Chained Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The values of the index used to determine the adjustments under this section are the latest published values when the Bureau of Labor Statistics publishes the initial value of the index for August of the year preceding the year to which the adjustment applies.

(b) For the purposes of this section, “statutory year” means the year preceding the first year for which dollar amounts are to be adjusted for inflation under sections that reference this section. For adjustments under chapter 290A, the statutory year refers to the year in which a taxpayer’s household income used to calculate refunds under chapter 290A was earned and not the year in which refunds are payable. For all other adjustments, the statutory year refers to the taxable year unless otherwise specified.[36]

Because the state begins its income tax calculations with federal taxable income, the standard deduction conforms to the federal level, which are themselves inflation-adjusted. Minnesota now decouples from federal treatment of the personal exemption (currently zeroed out) and offers its own dependent exemption of $4,250, adjusted for inflation by the same mechanism used for bracket widths, except that amounts are rounded down to the nearest $50.[37]

Missouri

In Missouri, inflation indexing is also cumulative, and simple in approach. The inflation factor is the percent by which CPI for the 12-month period ending the preceding August exceeds CPI for the 12-month period ending August 2015, rounded to the nearest dollar.

-

Beginning with the 2017 calendar year, the brackets of Missouri taxable income identified in subsection 1 of this section shall be adjusted annually by the percent increase in inflation. The director shall publish such brackets annually beginning on or after October 1, 2016. Modifications to the brackets shall take effect on January first of each calendar year and shall apply to tax years beginning on or after the effective date of the new brackets.

-

As used in this section, the following terms mean:

(1) “CPI,” the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers for the United States as reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, or its successor index;

(2) “CPI for the preceding calendar year,” the average of the CPI as of the close of the twelve month period ending on August thirty-first of such calendar year;

(3) “Net general revenue collected,” all revenue deposited into the general revenue fund, less refunds and revenues originally deposited into the general revenue fund but designated by law for a specific distribution or transfer to another state fund;

(4) “Percent increase in inflation,” the percentage, if any, by which the CPI for the preceding calendar year exceeds the CPI for the year beginning September 1, 2014 and ending August 31, 2015.[38]

Missouri’s standard deduction is indexed along with its bracket widths. As a part of the state’s tax conformity package in the aftermath of federal tax reform, policymakers permanently eliminated the personal exemption.

Montana

Montana adjusts its brackets based on the cumulative CPI change between June 2015 and June of the previous tax year. Unlike most states, therefore, it does not use 12-month averages as the start and end points, but instead uses CPI as of a particular month, which can introduce greater variance. Tax tables are rounded to the nearest $100.

“Inflation factor” means a number determined for each tax year by dividing the consumer price index for June of the previous tax year by the consumer price index for June 2015.

[…] By November 1 of each year, the department shall multiply the bracket amount contained in subsection (1) by the inflation factor for the following tax year and round the cumulative brackets to the nearest $100. The resulting adjusted brackets are effective for that following tax year and must be used as the basis for imposition of the tax in subsection (1) of this section.[39]

Mechanisms for indexing the standard deduction[40] and personal exemption[41] are identical, except that rounding is to the nearest $10 rather than $100.

Nebraska

In Nebraska, a recent conformity update decoupled from IRC § 1(f), which would otherwise have seen the state shift from CPI to Chained CPI. Brackets are adjusted for the change in CPI between the 12-month period ending August 2016 and the period ending August of the preceding taxable year, rounded to the nearest $10.

(3)(a) For taxable years beginning or deemed to begin on or after January 1, 2015, the minimum and maximum dollar amounts for each income tax bracket provided in subsection (2) of this section shall be adjusted for inflation by the percentage determined under subdivision (3)(b) of this section. The rate applicable to any such income tax bracket shall not be changed as part of any adjustment under this subsection. The minimum and maximum dollar amounts for each income tax bracket as adjusted shall be rounded to the nearest ten-dollar amount. If the adjusted amount for any income tax bracket ends in a five, it shall be rounded up to the nearest ten-dollar amount.

[…] (b)(ii) For taxable years beginning or deemed to begin on or after January 1, 2018, the Tax Commissioner shall adjust the income tax brackets based on the percentage change in the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers published by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics from the twelve months ending on August 31, 2016, to the twelve months ending on August 31 of the year preceding the taxable year. The Tax Commissioner shall prescribe new tax rate schedules that apply in lieu of the schedules set forth in subsection (2) of this section.[42]

Beginning with tax year 2019, adjustments for the standard deduction[43] and personal exemption[44] are made in the same manner but using a base year of the 12 months ending August 2017 rather than August 2016.

New Mexico

Although New Mexico does not have its own indexing provisions, taxpayers are permitted to claim the federal standard deduction, which is inflation-adjusted.

[adjusted to exclude] an amount equal to the standard deduction allowed the taxpayer for the taxpayer’s taxable year by Section 63 of the Internal Revenue Code, as that section may be amended or renumbered.[45]

North Dakota

North Dakota is the only state which currently switches to Chained CPI wholly on the basis of the new federal law, as its conformity date is current and the adjustment is based on the federal cost-of-living adjustment. While several other states also couple to some elements of the IRC’s adjustment mechanism, and South Carolina does so while—under a late 2018 conformity update—expressly adopting Chained CPI, North Dakota is unique in its straightforward adoption of the federal adjustment.

Under federal—and therefore also North Dakota—law, the calculation is based on the change between Chained CPI for the 12-month period ending August 2016 and the period ending the August prior to the tax year for which an adjustment is made. North Dakota also incorporates the federal rounding convention, which rounds to the next lowest $50. The state’s standard deduction is tied to the federal deduction and is thus inflation-adjusted automatically.

(The tax commissioner shall prescribe new rate schedules that apply in lieu of the schedules set forth in subdivisions a through e. The new schedules must be determined by increasing the minimum and maximum dollar amounts for each income bracket for which a tax is imposed by the cost-of-living adjustment for the taxable year as determined by the secretary of the United States treasury for purposes of section 1(f) of the United States Internal Revenue Code of 1954, as amended. For this purpose, the rate applicable to each income bracket may not be changed, and the manner of applying the cost-of-living adjustment must be the same as that used for adjusting the income brackets for federal income tax purposes.[46]

Ohio

Ohio, like Iowa, uses the GDP Deflator rather than a variation of CPI. (The deflator is contrasted with CPI in the discussion of Iowa’s approach to inflation adjustment.) Ohio avoids the convoluted approach adopted in Iowa by using the GDP Deflator for an annual rather than cumulative adjustment, simply multiplying the percentage increase in the GDP Deflator by the prior year’s tax tables to yield the new brackets. Rounding is to the nearest $50, and the relevant period is the calendar year. The personal exemption is adjusted in an identical manner.[47]

Except as otherwise provided in this division, in August of each year, the tax commissioner shall make a new adjustment to the income amounts prescribed in divisions (A)(2) and (3) of this section by multiplying the percentage increase in the gross domestic product deflator computed that year under section 5747.025 of the Revised Code by each of the income amounts resulting from the adjustment under this division in the preceding year, adding the resulting product to the corresponding income amount resulting from the adjustment in the preceding year, and rounding the resulting sum to the nearest multiple of fifty dollars. The tax commissioner also shall recompute each of the tax dollar amounts to the extent necessary to reflect the new adjustment of the income amounts. To recompute the tax dollar amount corresponding to the lowest tax rate in division (A)(3) of this section, the commissioner shall multiply the tax rate prescribed in division (A)(2) of this section by the income amount specified in that division and as adjusted according to this paragraph. The rates of taxation shall not be adjusted.

The adjusted amounts apply to taxable years beginning in the calendar year in which the adjustments are made and to taxable years beginning in each ensuing calendar year until a calendar year in which a new adjustment is made pursuant to this division. The tax commissioner shall not make a new adjustment in any year in which the amount resulting from the adjustment would be less than the amount resulting from the adjustment in the preceding year.[48]

Oregon

What begins as a fairly straightforward inflation adjustment has a curious twist in Oregon. Inflation indexing is based on the amount by which CPI for the 12 months ending August of the prior calendar year exceeds CPI for the second quarter of calendar year 1992, rather than a full 12-month period. This does not materially complicate calculations, as a cumulative adjustment can begin with almost any base period or amount, but it differs sufficiently from other states’ approaches as to make it easy to miss. Rounding is to the next lowest $50.

(c) For purposes of paragraph (b) of this subsection, the cost-of-living adjustment for any calendar year is the percentage (if any) by which the monthly averaged U.S. City Average Consumer Price Index for the 12 consecutive months ending August 31 of the prior calendar year exceeds the monthly averaged index for the second quarter of the calendar year 1992.

(d) As used in this subsection, “U.S. City Average Consumer Price Index” means the U.S. City Average Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (All Items) as published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics of the United States Department of Labor.

(e) If any increase determined under paragraph (b) of this subsection is not a multiple of $50, the increase shall be rounded to the next lower multiple of $50.[49]

While the bracket adjustment uses a three-month period as a baseline (meaning that the average of those three months is used, as opposed to the standard approach of using an annual average), the personal exemption credit is adjusted based on a six-month base level. The mechanism is similar, but uses a baseline of the first six months of 1986, and rounding is to the nearest dollar.[50] The standard deduction, meanwhile, uses a yearlong baseline, using the 12-month period ending August 2006, with rounding to the next lowest multiple of $50, as is used for the tax tables.[51]

Rhode Island

Rhode Island uses CPI as well, setting the inflation factor as the percentage by which CPI for the preceding year exceeds CPI for the 2000 base year, using a September to August year. The resulting tax tables are to be rounded to the next lowest $50.

(1) In general.

The cost-of-living adjustment for any calendar year is the percentage (if any) by which:

(a) The CPI for the preceding calendar year exceeds

(b) The CPI for the base year.

(2) CPI for any calendar year.

For purposes of paragraph (1), the CPI for any calendar year is the average of the consumer price index as of the close of the twelve (12) month period ending on August 31 of such calendar year.

(3) Consumer price index.

For purposes of paragraph (2), the term “consumer price index” means the last consumer price index for all urban consumers published by the department of labor. For purposes of the preceding sentence, the revision of the consumer price index that is most consistent with the consumer price index for calendar year 1986 shall be used.

(4) Rounding.

(a) In general.

If any increase determined under paragraph (1) is not a multiple of $50, such increase shall be rounded to the next lowest multiple of $50.[52]

The state’s standard deduction is adjusted using a base year of 1988,[53] and its personal exemption using a base year of 1989,[54] with identical rounding conventions.

South Carolina

As a state which begins its calculations with federal taxable income, South Carolina has historically brought in the federal standard deduction and personal exemption, both of which are inflation-indexed. The state also incorporated federal inflation adjustment provisions for its tax brackets, though it substituted its own baseline year (1994). In late 2018, as part of a broader conformity bill, South Carolina updated its inflation adjustment provisions, adopting Chained CPI in line with the federal government, with a cumulative adjustment capped at 4 percent a year. Rounding is to the nearest $10.

Beginning on December 15, 2018, and each December fifteenth thereafter, the department shall cumulatively adjust the brackets in Section 12-6-510 using the Chained Consumer Price Index for All Consumers, as published by the Bureau of Labor and Statistics of the Department of Labor, pursuant to Internal Revenue Code Section (1)(f). However, the adjustment may not exceed four percent a year, and notwithstanding the rounding amount provided in (1)(f)(7), the rounding amount is ten dollars. The brackets, as adjusted, apply instead of those provided in Section 12-6-510 for taxable years beginning in the succeeding calendar year. Inflation adjustments must be made cumulatively to the income tax brackets.[55]

With the suspension of the federal personal exemption, South Carolina adopted its own dependent exemption, with identical conventions.[56] The standard deduction continues to track federal levels, which are themselves inflation-indexed.

Utah

Utah, which features a flat tax and thus does not have brackets to inflation-proof, takes a unique approach to its standard deduction, offering a credit—not deduction—worth 6 percent of the taxpayer’s federal standard deduction. The result is slightly more generous than if the state simply offered a standard deduction, since the income tax rate is currently 4.95 percent, and the credit is worth 6 percent of the standard deduction. Since the credit incorporates the value of the federal standard deduction, it also captures its inflation adjustment regime.

[…] a claimant may claim a nonrefundable tax credit against taxes otherwise due under this part equal to the sum of:

(a)(i) for a claimant that deducts the standard deduction on the claimant’s federal individual income tax return for the taxable year, 6% of the amount the claimant deducts as allowed as the standard deduction on the claimant’s federal individual income tax return for that taxable year.[57]

Vermont

Vermont uses a cumulative CPI adjustment, increasing the statutory bracket widths by the percentage by which CPI for the most recently completed September to August 12-month period exceeds that for the period ending August 2002, generally following Internal Revenue Code procedures (except for the substitution of CPI), including a rounding convention of the next lowest $50. The process is identical for the state’s standard deduction and personal exemption.[58]

The amounts of taxable income shown in the tables in this section shall be adjusted annually for inflation by the Commissioner of Taxes using the Consumer Price Index adjustment percentage, in the manner prescribed for inflation adjustment of federal income tax tables for the taxable year by the Commissioner of Internal Revenue, beginning with taxable year 2003; provided, however, notwithstanding 26 U.S.C. § 1(f)(3), that as used in this subdivision, “consumer price index” means the last Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers published by the U.S. Department of Labor.[59]

Wisconsin

Wisconsin’s inflation adjustments are also cumulative but are based on CPI levels for specific months rather than averaged over a 12-month period, as is more typical. Adjustments are based on the differential between CPI for August of the immediately preceding year and August 2008 and are only operable if the adjustment represents an increase. Rounding is to the nearest $10. For the standard deduction, the base period is August 2009.[60]

(b) For taxable years beginning after December 31, 2009, the maximum dollar amount in each tax bracket, and the corresponding minimum dollar amount in the next bracket, under subs. (1p)(d), (1q)(c), and (2)(g)4., (h)4., (i)3., and (j)3., and the dollar amount in the top bracket under subs. (1p)(e), (1q)(d), and (2)(g)5., (h)5., (i)4., and (j)4., shall be increased each year by a percentage equal to the percentage change between the U.S. consumer price index for all urban consumers, U.S. city average, for the month of August of the previous year and the U.S. consumer price index for all urban consumers, U.S. city average, for the month of August 2008, as determined by the federal department of labor, except that for taxable years beginning after December 31, 2011, the adjustment may occur only if the resulting amount is greater than the corresponding amount that was calculated for the previous year.

(c) Each amount that is revised under this subsection shall be rounded to the nearest multiple of $10 if the revised amount is not a multiple of $10 or, if the revised amount is a multiple of $5, such an amount shall be increased to the next higher multiple of $10. The department of revenue shall annually adjust the changes in dollar amounts required under this subsection and incorporate the changes into the income tax forms and instructions.[61]

District of Columbia

The federal district aligns its standard deduction with the federal standard deduction, which is indexed for inflation.

(iv) For taxable years beginning after December 31, 2017, the standard deduction as prescribed in section 63(c) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986.[62]

Conclusion

Indexing is an essential feature of a modern tax code—but many states have yet to update their codes or have only done so incompletely. States which have yet to adopt indexation of brackets, deductions, and exemptions should do so at the earliest opportunity. States which already index these features of their tax codes are well-advised to ensure that their indexation measures are simple, predictable, and complete. Four decades have passed since inflation indexing burst onto the scene. No additional decades should be needed for all states to incorporate this important feature into their tax codes.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeAppendix: Statutory Citations

| State | Brackets |

|---|---|

| Arizona | A.R.S. § 43-1011(C) |

| Arkansas | A.C.A. § 26-51-201(d) |

| California | Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 17073.5(d) |

| Colorado | Flat Tax |

| Idaho | I.C. § 63-3024 |

| Illinois | Flat Tax |

| Iowa | I.C.A. § 422.4(1) |

| Kentucky | Flat Tax |

| Maine | 36 M.R.S.A. § 5403(1) |

| Michigan | Flat Tax |

| Minnesota | M.S.A. §§ 290.0132(26f) and 270C.22 |

| Missouri | V.A.M.S. 143.011(4-5) |

| Montana | MCA 15-30-2103(2) |

| Nebraska | Neb.Rev.St. § 77-2715.03(3) |

| North Dakota | N.D. Cent. Code § 57-38-30.3(1)(g) |

| Ohio | R.C. § 5747.02(A)(4)(b)(5) |

| Oregon | O.R.S. § 316.037(1) |

| Rhode Island | Gen.Laws 1956, § 44-30-2.6 |

| South Carolina | Code 1976 § 12-6-520 |

| Tennessee | Flat Tax |

| Utah | Flat Tax |

| Vermont | 32 V.S.A. § 5822(b)(2) |

| Wisconsin | W.S.A. 71.06(2e) |

| State | Statutory Citation |

|---|---|

| Arizona | A.R.S. § 43-1041(H) |

| California | Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 17073.5(d) |

| Colorado | Conforms to Federal |

| Idaho | Conforms to Federal |

| Iowa | I.C.A. § 422.21(5) |

| Kentucky | KRS § 141.081(2) |

| Maine | Conforms to Federal |

| Maryland | MD Code, Tax – General, § 10-217 |

| Minnesota | Conforms to Federal |

| Missouri | Conforms to Federal |

| Montana | MCA 15-30-2132(2) |

| Nebraska | Neb.Rev.St. § 77-2716.01(3)(b) |

| New Mexico | Conforms to Federal |

| North Dakota | Conforms to Federal |

| Oregon | O.R.S. § 316.695(3)(f) |

| Rhode Island | Gen.Laws 1956, § 44-30-2.6(c)(2)(C)(7) |

| South Carolina | Conforms to Federal |

| Utah | Percentage of Federal |

| Vermont | 32 V.S.A. § 5811(21)(C)(iv) |

| Wisconsin | W.S.A. § 71.05(22)(dt) |

| District of Columbia | DC ST § 47-1801.04 |

| State | Personal Exemption |

|---|---|

| Arizona | A.R.S. § 43-1043(D) |

| Arkansas | A.C.A. § 26-51-501(d) |

| California | Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 17054(i) |

| Illinois | 35 ILCS 5/204(d-5) |

| Michigan | MCL 206.30(7) |

| Minnesota | Conforms to Federal |

| Montana | MCA 15-30-2114(6) |

| Nebraska | Neb.Rev.St. § 77-2716.01(1)(b) |

| Ohio | R.C. § 5747.025(C) |

| Oregon | O.R.S. § 316.085(3) |

| Rhode Island | Gen.Laws 1956, § 44-30-2.6(c)(2)(E)(3) |

| South Carolina | Code 1976 § 12-6-1140(13). |

| Vermont | 32 V.S.A. § 5811(21)(C)(iv) |

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe[1] Those states are Alabama, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Kansas, Maryland, Mississippi, Virginia, and West Virginia.

[2] For a “grading” of state individual income tax inflation adjustment regimes, see Jared Walczak, “Grading the States on Inflation Indexing,” Tax Notes State 93:1291 (Sept. 30, 2019).

[3] Harley T. Duncan, “The Inflation Tax: The Case for Indexing Federal and State Income Taxes,” Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations, Paper M-117, January 1980, vi.

[4] Milton Friedman, “Monetary Correction: A Proposal for Escalator Clauses to Reduce the Costs of Ending Inflation,” Institute of Economic Affairs, Occasional Paper No. 41, 1974, 9-10, https://miltonfriedman.hoover.org/friedman_images/Collections/2016c21/IEA_1974.pdf.

[5] Duncan, “The Inflation Tax: The Case for Indexing Federal and State Income Taxes,” 21.

[6] Stephen J. Entin, “Tax Indexing Turns 30,” Tax Foundation, Mar. 11, 2015, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-indexing-turns-30/.

[7] Keith D. Malone, Kathy Lewis-Adler, and Joseph Joiner, “The Alabama Tax System: Origins and Current Issues,” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 1:14 (October 2011), http://www.ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_1_No_14_October_2011/1.pdf.

[8] Duncan, “The Inflation Tax: The Case for Indexing Federal and State Income Taxes,” 13.

[9] Reed Shuldiner, “Indexing the Tax Code,” University of Pennsylvania Law School Faculty Scholarship Paper 1262, 1993, 549, https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2262&context=faculty_scholarship.

[10] Michael R. Baye and Dan Black, “Indexation and the Inflation Tax,” Cato Institute, Policy Analysis No. 39, July 12, 1984, https://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/indexation-inflation-tax.

[11] Rob McClelland, “Differences Between the Traditional CPI and the Chained CPI,” Congressional Budget Office, Apr. 19, 2013, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/44088.

[12] Id.

[13] David Brauer and Noah Meyerson, “How Does Growth in the Cost of Goods and Services for the Elderly Compare to That of the Overall Population?” Congressional Budget Office, Apr. 19, 2013, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/44090.

[14] A.R.S. § 43-1011(C).

[15] A.R.S. § 43-1041(H).

[16] A.R.S. § 43-1043(D).

[17] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers,” https://www.bls.gov/cpi/tables/home.htm.

[18] A.C.A. § 26-51-201(d).

[19] A.C.A. § 26-51-501(d).

[20] Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 17041(h).

[21] Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 17073.5(d).

[22] Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 17054(i).

[23] C.R.S.A. § 39-22-104.

[24] I.C. § 63-3024.

[25] 35 ILCS 5/204(d-5).

[26] Jared Walczak, “Twelve Things to Know About the ‘Fair Tax for Illinois,’” Tax Foundation, Mar. 11, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/illinois-fair-tax/.

[27] The new base year will be the year in which the contingent clauses take effect, which is to be determined by tax triggers. See Jared Walczak, “What’s in the Iowa Tax Reform Package,” Tax Foundation, May 9, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/whats-iowa-tax-reform-package/.

[28] I.C.A. § 422.21(5).

[29] I.C.A. § 422.4(1).

[30] KRS § 141.081(2).

[31] It does allow for modest substitution within categories.

[32] Michael Ng and David Wessel, “The Hutchins Center Explains: The Chained CPI,” The Brookings Institute, Dec. 7, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2017/12/07/the-hutchins-center-explains-the-chained-cpi/.

[33] 36 M.R.S.A. § 5403(1).

[34] MD Code, Tax – General, § 10-217(d).

[35] MCL 206.30(7).

[36] M.S.A. §§ 290.0132(26f) and 270C.22.

[37] M.S.A. § 290.1021.

[38] V.A.M.S. 143.011(4-5).

[39] MCA 15-30-2101(11) and -2103(2).

[40] MCA 15-30-2132(2).

[41] MCA 15-30-2114(6).

[42] Neb.Rev.St. § 77-2715.03(3).

[43] Neb.Rev.St. § 77-2716.01(3)(b).

[44] Neb.Rev.St. § 77-2716.01(1)(b).