Key Findings

- The Texas Margin TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. is routinely the subject of scrutiny from tax scholars because of its complexity and unfairness.

- The Margin Tax creates tax pyramidingTax pyramiding occurs when the same final good or service is taxed multiple times along the production process. This yields vastly different effective tax rates depending on the length of the supply chain and disproportionately harms low-margin firms. Gross receipts taxes are a prime example of tax pyramiding in action. , the process of taxes stacking on top of other taxes as a product moves through the production chain.

- The Margin Tax has attracted many lawsuits because of its structure. Of the three most notable challenges, one was decided in favor of the taxpayers, another in favor of the state, and one is still ongoing.

- The Margin Tax was expected to bring in $5.9 billion each year, but instead, the tax brought in $4.45 billion its first year, and $4 billion the next.

- Gross receipts-style taxes exist at the state level in just three states other than Texas: Delaware, Washington, and Ohio.

- Many states have repealed gross receipts-style taxes in the last fifteen years: Michigan (repealed 2011), Kentucky (enacted 2005, repealed 2006), New Jersey (repealed 2006), and Indiana (repealed 2002).

- Repealing the Margin Tax would improve Texas’ ranking in the State Business Tax Climate Index from 10th to 3rd best in the country.

- One analysis shows that Margin Tax repeal would create 41,500 new jobs, $3.4 billion in new investment, and $9.8 billion in real disposable income over a four year period.

- Another analysis shows that if the Margin Tax had never been created, personal income would have grown as much $46.3 billion cumulatively between 2006 and 2013, a 0.57 percent increase over actual personal income growth during that period.

Introduction

There are a lot of reasons to live and do business in Texas. The state has vast natural resources, large urban centers, access to ports, and, for the most part, well-structured fiscal policies that have contributed to substantial growth. However, one element of the state’s fiscal structure that has created serious controversy is the state’s Margin Tax.

The Texas Margin Tax is one of the most interesting experiments in tax policy today. Since going into effect in 2008, it has attracted criticism from experts in the field, attracted lawsuits from businesses that must comply with it, and attracted legislative changes as political pressure around the tax continues to mount. In fact, in the last legislative session, at least 89 bills were filed in the Texas Legislature aimed at changing the tax in some way, with eight aimed at repealing it entirely.[1]

This paper reviews the timeline of the adoption of the tax, discusses the calculation procedures that taxpayers must go through to complete a tax return, and reviews major lawsuits against the Margin Tax, finding that the unique structure of the tax is a problem for taxpayers, legislators, and judges.

The paper then reviews the economic literature surrounding gross receipts taxes generally, demonstrating that gross receipts taxes have a centuries-old track record of economic damage and unpopularity among academics.

The paper closes with a review of two studies that examine how repealing the Margin Tax would affect the economy. Both find that repeal would increase personal income growth while boosting revenues from other taxes. Texas, which currently ranks 10th in the Tax Foundation’s State Business Tax Climate Index, would improve to 3rd best if the tax were repealed, as this would make Texas’ tax code more simple, neutral, and stable.

Repealing the Margin Tax is the most straightforward option for improving Texas’ tax structure. As one academic put it, gross receipts taxes like the Margin Tax “do not belong in any program of tax reform.”[2]

The Margin Tax Launch Was Plagued by Confusion and Revenue Shortfalls

In 2005, a Texas Supreme Court decision declared the Texas school finance system unconstitutional, because it raised money from what was, in effect, a statewide property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services. .[3] In an effort to increase school funding from a source other than property taxes, policymakers chose to substantially alter the Texas Franchise Tax, which had been levied in some form since the 1800s. The new tax was intended to raise an additional $3 billion in revenue each year.[4]

The result of this legislative exercise, conducted during a special session of the Texas Legislature, was the 2008 enactment of what is now commonly called the Texas Margin Tax, a complicated hybrid of a gross receipts taxGross receipts taxes are applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like compensation, costs of goods sold, and overhead costs. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and applies to transactions at every stage of the production process, leading to tax pyramiding. and a tax on business profits.

The Texas Franchise Tax prior to 2008 was mainly based on the capital stock of a company, but the new Margin Tax is based on total revenue of the company with certain deductions (detailed below). The Margin Tax also expanded the base of payers of the Franchise Tax to new business categories. While the Franchise Tax only applied to C corporations, S corporations, and LLCs, the current Margin Tax applies to partnerships, business trusts, and professional associations as well.[5]

The Margin Tax is unique to Texas, so tax officials did not have a good understanding of how the tax would work, how much revenue it would bring in, or what to expect as they began collection. Because of this, the year before the tax took full effect, officials required that large companies file an informational tax return.[6]

After full implementation, however, revenue did not materialize as anticipated. While official revenue projections had suggested the Margin Tax would raise $5.9 billion per year, and the informational returns the previous year had suggested it would raise $5 billion, the 2008 collections totaled only $4.45 billion.[7] In 2009, collections fell even further to below $4 billion. This shortfall in part led noted tax commentator Billy Hamilton to call the Margin Tax “the tax that fell to earth.”[8]

The Margin Tax Structure Is Unnecessarily Complex and Burdensome

The revenue shortfall of the Margin Tax was in part caused by its structure. In an effort to avoid political opposition, the tax was constructed to allow taxpayers to choose the lower of three base calculations (later revised to four bases). While this might have assuaged political concerns, each of these bases creates economic distortions, and requiring four separate calculations increases compliance costs. Figure 1 details how taxpayers determine their tax liability.

This unique and complex calculation of the Texas Margin Tax base is a frequent gripe of tax policy experts. Shortly after the passage of the tax, Professor John Mikesell of Indiana University described it as

a badly designed business profits tax, like those that emerged in the newly independent states of the former Soviet Union . . . combin[ing] all the problems of minimum income taxation in general—excess compliance and administrative cost, penalization of the unsuccessful business, undesirable incentive impacts, doubtful equity basis—with those of taxation according to gross receipts.[9]

The experience of business owners echoes Mikesell’s concerns, with at least one owner complaining in 2009 that accountant fees have often doubled because of the tax’s complexity.[10] In 2013, the legislature made the $1 million revenue exemption permanent, helping some small businesses but leaving the same complexity challenges for businesses still paying the tax.

The Margin Tax Has Attracted Major Lawsuits

Administrative problems associated with the Margin Tax did not stop after adoption, however, as the new tax proved to be a magnet for lawsuits. These legal challenges—three in particular—mostly center on how difficult it is to interpret the provisions of the Margin Tax and apply them to specific taxpayers.

In re: Nestlé USA Inc.

In 2012, the Texas Supreme Court heard one of the first major constitutional challenges to the Margin Tax.[11] In this case, Nestlé challenged the provision that provides a 0.5 percent rate applicable to retailers and wholesalers and a 1.0 percent rate applicable to everyone else. Nestlé first argued that having different rates based on the organization of a business violates the Texas Constitution’s requirement that taxation be “equal and uniform,” and also argued that the company’s activities within Texas were primarily wholesale and retail, meaning it should be able to pay the 0.5 percent rate instead of the 1 percent that was being collected from them.

Nestlé ultimately lost. The Court first rejected Nestlé’s non-uniformity argument, saying, “classifying taxpayers for purposes of an occupation tax is not an exception to the Equal and Uniform Clause but a consequence of it. The value of an occupation derives not from the fact that it involves activity—a mere expenditure of energy—but from its nature, pursuits, and rewards.”[12]

The Court also rejected Nestlé’s argument about its wholesale status, finding that Nestlé’s out-of-state manufacturing operations made it subject to the 1 percent rate.

Titan Transportation, LP v. Combs

In 2014, in Titan Transportation, LP v. Combs,[13] Titan challenged its tax assessment by arguing that it should be able to exclude payments made to subcontractors from its total revenue for purposes of calculating its Margin Tax liability. Titan uses subcontractors to deliver “aggregate” (used as an ingredient in the construction of roads, houses, and buildings) to real-property construction sites. Titan is obligated by contract to share the proceeds from the deliveries with the subcontractors.

As a result, Titan claimed that these payments to the subcontractors were properly excluded under former Tax Code § 171.1011(g)(3).[14] This provision stated that a taxable entity must exclude certain flow-through payments mandated by contract to be distributed to other entities. Applicable payments include subcontracting payments made for the purposes of providing services, labor, or materials in connection with the design, construction, remodeling, or repair of real property. The Court ultimately agreed with Titan and ruled that the Comptroller improperly denied the revenue exclusion that Titan was seeking.

Hallmark Marketing Company, LLC v. Combs

Another important challenge to the Margin Tax, still ongoing, is Hallmark Marketing Company, LLC v. Combs, which highlights how confusing the definitional instructions of the Margin Tax can be.[15] In the tax year at issue, Hallmark grossed $4.516 billion in receipts but sustained $628 million in investment losses and capital asset writedowns. The margin tax statute taxes “only the net gain from the sale” of investment or capital asset sales.[16] Hallmark argues that it should be taxed only on its $4.516 billion in receipts, since it had no “net gain” from the investment and capital sales, with a resulting low apportionment factor for Texas. The state argues that Hallmark should subtract the loss and pay tax on the net figure, $3.887 billion, with the resulting higher apportionmentApportionment is the determination of the percentage of a business’s profits subject to a given jurisdiction’s corporate income tax or other business tax. US states apportion business profits based on some combination of the percentage of company property, payroll, and sales located within their borders. factor for Texas.

In November 2014, a three-judge appellate panel upheld the state’s interpretation, saying either reading was reasonable but that the state’s version should get deference. Hallmark’s has filed an appeal with the Texas Supreme Court.

Gross Receipts Taxes Cause Tax Pyramiding

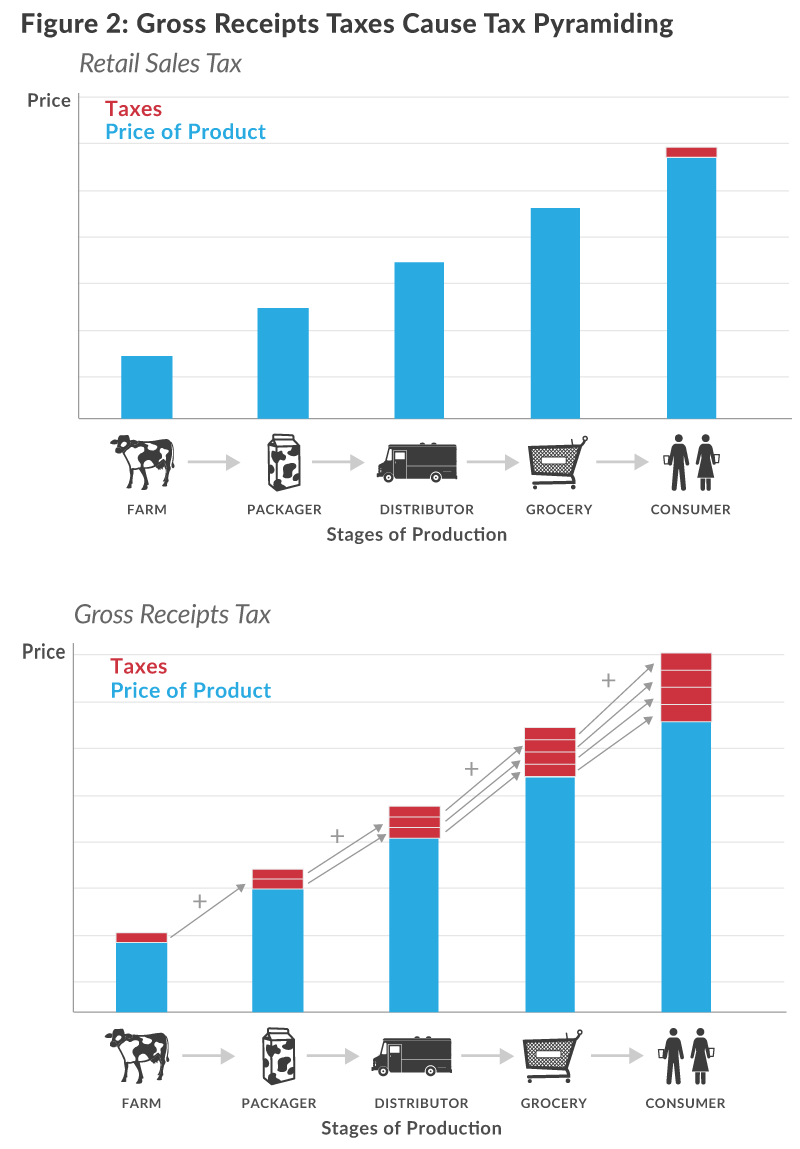

While legal minds have found many technical problems with the Margin Tax, economists have been criticizing the structure of gross receipts taxes like the Margin Tax for centuries.[17] Their chief criticism is that gross receipts taxes “pyramid,” or stack on top of one another as products move through the production chain.

By examining the production process for milk, Figure 2 shows how a tax based on gross receipts results in many taxes being levied along the chain of production. From the dairy farm, to the processing plant for homogenization, to the distributor, to the grocer, each new stage of production adds value to the product as it gets closer to the consumer. The first image in the chart shows how a retail sales tax is levied once and only once, on the final price of the product when it is purchased by a consumer. A gross receipts tax, however, has a tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. much larger than any of these other taxes, because it is levied on the total price of the product every time it exchanges hands.

The Academic Literature Is Heavily Stacked Against Gross Receipts Taxes

While there are only five U.S. states still utilizing gross receipt taxes today, they have been part of tax regimes in Europe dating to at least the 13th century and in the United States since the mid-19th century.[18] Adam Smith suggested in 1776 that Great Britain’s economic superiority to Spain was in part linked to the damaging nature of the Spanish Alcabala, a gross receipts tax. He noted:

It [is levied] upon the sale of every sort of property whether movable or immovable, and it is repeated every time the property is sold. The levying of this tax requires a multitude of revenue officers sufficient to guard the transportation of goods, not only from one province to another, but from one shop to another. It subjects not only the dealers in some sorts of goods, but those in all sorts, every farmer, every manufacturer, every merchant and shopkeeper, to the continual visits and examination of the tax-gatherers.[19]

Meanwhile, in Spain, Enlightenment thinker and Spanish statesman Don Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos concurred, saying that the Alcabala tax “surprised local produce from the moment it was born, chasing and biting it throughout its circulation, without ever losing sight of or releasing its prey until the last moment of consumption.”[20] Ultimately, the tax was abolished in the Spanish tax reform of 1845.[21]

John Due notes that while the Spanish Alcabala was one of the more notorious examples of gross receipts taxes, these taxes were experimented with in many countries:

[A] turnover tax was introduced in Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, and other European countries (and for a time in Canada) after World War I. It was also widely adopted by the Latin American countries. . . . The defects of the turnover tax have been made extremely clear by long experience and of course have been responsible for the abandonment of the tax by most countries.[22]

This academic criticism has carried forward to the current day in the United States, where only a few states still maintain them (see Figure 3). Noted tax expert John L. Mikesell argues that gross receipts taxes fail almost every test for sound revenue sources. First, because their base is often larger than the state’s gross product, gross receipts taxes do not properly reflect the amount of state services used by firms. This means that taxing of businesses through a gross receipts tax does not conform to the “benefit principle” of taxation, which is an established principle of trying to match taxes paid with government benefits received.[23]

Gross receipts taxes also fail the transparency test, because effective rates are so much higher than statutory rates due to tax pyramiding. Mikesell notes that in Washington State, for example, the Business & Occupation Tax creates effective tax rates which average 2.5 times as much as the statutory rate.[24]

Further, gross receipts taxes unnecessarily distort market choices by both individuals and businesses because they penalize trade among firms. In some cases, pyramiding creates an artificial incentive to vertically integrate an industry to avoid the gross receipts tax, even if doing so would not make sense otherwise. Finally, Mikesell finds no evidence to suggest that gross receipts taxes are any more stable in producing revenues than value-added taxes.[25]

Chamberlain and Fleenor (2006) demonstrate that gross receipts taxes effectively impose different tax rates across different industries, as industries with longer production processes are taxed many times before they can bring products to market.[26] This is a violation of the well-established tax principle of neutrality, which states that similarly situated taxpayers should be treated the same.

Ross (2014) echoes many of these concerns, calling gross receipts taxes the “worst offender” at taxing business inputs compared to any other tool in the state and local tax toolkit. He argues that gross receipts taxes are the least transparent taxes states levied today.[27]

Diamond and Mirrlees (1971) note that optimal tax structures for competitive industries are defined as having no taxes on intermediate goods, arguing that such taxes cause firms to act inefficiently by looking for substitutes for heavily taxed inputs. They counter that a tax on final products could raise revenue while minimizing harmful effects.[28] Testa and Mattoon (2007) find that value-added taxes are better business tax tools than gross receipts taxes. They also argue that “geographically, receipts have little to do with the venue of production, especially as value and supply chains are widening out worldwide.”[29]

The consensus against gross receipts taxes is so strong in the tax field that when a Kentucky tax commission suggested implementing one, Tax Analysts Deputy Publisher David Brunori flatly remarked, “Gross receipts taxes are terrible. And I’m shocked that a ‘blue ribbon’ panel would ever contemplate their use.”[30]

Few States Maintain Gross Receipts Taxes Today

Due to their poor academic track record, few states still maintain gross receipts taxes, and recent years have seen many states repealing their gross receipts taxes. Today, aside from the Texas Margin Tax, gross receipts-style taxes exist at the state level in just three states: Delaware, Washington, and Ohio (See Figure 3). Virginia additionally levies a local gross receipts tax called the BPOL (Business Professional Occupation License Tax).

The most recent repeal of a gross receipts tax was the 2011 abolition of the notorious Michigan Business Tax, which Governor Rick Snyder called “the dumbest tax in the United States.”[31] Other recent examples include the repeal of the Indiana gross receipts tax in 2002, the 2006 repeal of the New Jersey gross receipts tax, which was just four years old,[32] and the repeal of the very short-lived Kentucky gross receipts tax, which was enacted in 2005, and immediately repealed in 2006.[33]

Repeal of the Margin Tax Would Improve Texas’ State Business Tax Climate Index Ranking

The Tax Foundation’s State Business Tax Climate Index is a ranking tool that allows legislators, taxpayers, and the media to compare how each state structures its tax code. The ranking comprises over a hundred variables that measure tax rates and bases across five tax categories: individual income taxes, corporate taxes, sales taxes, unemployment insurance taxes, and property taxes.

While there are many ways to measure tax collections and burdens, this ranking gives state policymakers constructive advice on what they can do to make their tax code more competitive, such as utilizing broader bases, lower rates, and less economic distortion. The Texas Margin Tax does not fare well in the Index, scoring 39th in the corporate tax portion of the ranking. Further still, the Margin Tax hurts the state’s score in the individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. component of the Index as well (the state ranks 6th, instead of a perfect ranking of 1st), because the Margin Tax applies to S corporations and LLCs, which in most states are subject only to the individual income tax.

Repealing the Margin Tax would move Texas from a rank of 10th to 3rd, giving the state one of the most competitive tax climates in the country overall, behind only Wyoming and South Dakota (Figure 4). The repeal of the Margin Tax would give Texas the most competitive corporate tax climate in the country, achieving a perfect score, and would improve the state’s individual income tax component to a perfect score as well.

| Source: Tax Foundation, 2015 State Business Tax Climate Index; Tax Foundation analysis. | ||

| Current Score | With Margin Tax Repeal | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 10 | 3 |

| Corporate | 39 | 1 |

| Individual | 6 | 1 |

| Sales | 36 | 36 |

| Unemployment Insurance | 15 | 15 |

| Property | 36 | 36 |

Dynamic Models Find Margin Tax Repeal Would Promote Job Growth and Investment

Dynamic econometric analyses of the effects of Margin Tax repeal have yielded favorable jobs and GDP growth numbers as well. A 2012 analysis by the Beacon Hill Institute at Suffolk University found that Margin Tax repeal in 2013 would have created 41,500 new jobs by 2017, $3.4 billion in new investment, and $9.8 billion in real disposable income over the same period. This would have made $209 per capita in additional real disposable income (Figure 5).

| Year | Private Employment (jobs) | Investment (in billions) |

Real Disposable Income (in billions) |

Real Disposable Income Per Capita |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Beacon Hill Institute. | ||||

| 2013 | 31,500 | $3.2 | $6.4 | $159 |

| 2017 | 41,500 | $3.4 | $9.8 | $209 |

One of the more useful attributes of dynamic analysis like this is that it can show the full effects of a tax change on state and local revenues. In the case of Margin Tax repeal, the authors note that because of economic growth effects from repealing the tax, state coffers would gain revenue from other taxes.[34] So while the Margin Tax repeal would reduce state revenue by $4.5 billion, other taxes would bring in an additional $1 billion in new revenue due to economic growth (Figure 6).[35]

| Source: Beacon Hill Institute. | |||

| State Taxes | 2013 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Franchise Tax | -$4,210 | -$4,531 | |

| Sales Tax | $133.0 | $188.5 | |

| Vehicle | $4.4 | $6.7 | |

| Motor Fuels | $3.8 | $5.6 | |

| Oil & Gas | $40.8 | $52.2 | |

| Insurance Occupation | $5.2 | $7.6 | |

| Other Revenue | $97.8 | $125.2 | |

| Subtotal | -$3,925.0 | -$4,145.2 | |

| Local Taxes | |||

| Sales Tax | $47.2 | $68.8 | |

| Residential Property Tax | n/a | n/a | |

| Business Property Tax | $357.5 | $461.7 | |

| Other Revenue | $54.8 | $70.3 | |

| Subtotal | $459.5 | $600.8 | |

| Total | -$3,465.50 | -$3,544.40 | |

While the Beacon Hill study is forward looking, another recent analysis by John Merrifield and Corey DeAngelis of the University of Texas at San Antonio looks backward to show how the Texas economy would have grown assuming the Margin Tax had never been put in place.[36] For the purposes of their model, they assume that the state instead enacted a constitutional spending limitation barring spending increases in excess of population plus inflation, starting in 2006.

Figure 7 details the findings of Merrifield and DeAngelis. The left column (Modest Growth Effects) shows income and revenue impacts assuming that a state growth rate increases by 0.251 percent for each percent drop in the state’s marginal tax rateThe marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. relative to the national average. The right column (Robust Growth Effects) shows income and revenue impacts assuming that a state growth rate increases by 0.374 percent for each percent drop in the state’s marginal tax rate relative to the national average.[37]

The authors show that cumulative disposable personal income would have grown between $30.5 to $46.3 billion between 2006 and 2013. This is between a 0.38 percent and 0.57 percent increase over how personal income actually grew over this period. This economic growth would create somewhere between $1.4 and $2.2 billion in additional tax revenues.

| Source: Merrifield & DeAngelis. | ||

| Modest Growth Effects | Robust Growth Effects | |

|---|---|---|

| Cumulative Extra Personal Income | $30,505 | $46,335 |

| Percent Increase above Actual | 0.38% | 0.57% |

| Cumulative Tax revenue Increase from Increased Growth | $1,425 | $2,164 |

| Percent Increase above Actual | 0.48% | 0.73% |

Conclusion

The Texas Margin Tax does not raise revenue in an equitable, simple, or transparent way. While policymakers aimed to increase education spending from a source other than property taxes, they inadvertently created one of the worst business taxes in the country. While the academic evidence against gross receipts taxes alone should be sufficient impetus for repeal, Texas policymakers now know from direct experience the problems that businesses face with complying with this complex tax. The Margin Tax experiment has failed, and it should be retired.

[1]* This report was made possible by a grant from the Texas Conservative Coalition Research Institute. The author would like to thank Chris Stephens and Johannes Schmidt for their assistance.

83rd Legislative Session Bills: Tracking Franchise Tax Bills, Texas Tribune, http://www.texastribune.org/session/83R/bills/trackers/franchise-tax-bills/.

[2] John L. Mikesell, Gross Receipts Taxes in State Government Finances: A Review of Their History and Performance, Tax Foundation & Council on State Taxation Background Paper No. 53 (Jan. 2007) at 2, http://www.taxfoundation.org/legacy/show/2180.html.

[3] Neeley v. West Orange-Cove I.S.D. (Nov. 22, 2005).

[4] Chris Atkins, Appropriation by Litigation: Estimating the Cost of Judicial Mandates for State and Local Education Spending, Tax Foundation Background Paper No. 55 (July 2007), https://taxfoundation.org/article/appropriation-litigation-estimating-cost-judicial-mandates-state-and-local-education-spending. See also Texas Taxpayers and Research Association, Understanding the Texas Franchise—or “Margin”—Tax (Oct. 2011), http://www.ttara.org/files/document/file-4ea5bda9239ef.pdf.

[5] Id.

[6] Joseph Henchman, Texas Margin Tax Experiment Failing Due to Collection Shortfalls, Perceived Unfairness for Taxing Unprofitable and Small Businesses, and Confusing Rules, Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 279 (Aug. 17, 2011), https://taxfoundation.org/article/texas-margin-tax-experiment-failing-due-collection-shortfalls-perceived-unfairness-taxing.

[7] Id.

[8] See Billy Hamilton, The Tax That Fell to Earth: Lessons From the Texas Margin Tax’s Launch, State Tax Notes, Sept. 6, 2010.

[9] See Mikesell, supra note 2, at 4 n.6, http://www.taxfoundation.org/legacy/show/2180.html.

[10] Don Bolding, Texas Legislature lifts some ‘margin tax’ burden off owners, Killeen Daily Herald, July 12, 2009, http://kdhnews.com/business/texas-legislature-lifts-some-margin-tax-burden-off-owners/article_82abab24-45df-5b52-95da-60af183399a4.html?mode=story.

[11] In re: Nestle USA Inc., No. 12-0518 (Tex. 2012).

[12] Id. at 17.

[13] Titan Transportation, LP v. Combs, et al., No. 03-13-00034-CV (Tex. App. 3rd Ct. 2014).

[14] Tex. Tax Code §171.1011(g)(3) (2006) (amended 2013).

[15] Hallmark Marketing Company, LLC v. Combs, No. 13-14-00093-CV (Tex. App. 13th Ct. 2014).

[16] Tx. Tax Code § 171.105(b).

[17] While the Margin Tax is admittedly a hybrid of a gross receipts tax and an income tax, its base definition results in more tax pyramiding than a traditional corporate income tax, and it is possible for businesses to pay a hefty Margin Tax bill even in years when they are unprofitable. For example, a business might bring in substantial revenue in a given year, but capital purchases could cause the firm to not have any profits. Still, the firm could pay a Margin Tax bill under any of the three calculation methods.

[18] See Mikesell, supra note 2.

[19] Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776) (Edwin Cannan, ed., Methuen & Co., Ltd. 1904), http://www.econlib.org/library/Smith/smWN.html.

[20] See Gaspar de Jovellanos, Obras publicadas é inéditas de D. Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, Vol. 50 (M. Rivadeneyra, ed. 1859) (translation by author) at 118, http://books.google.com/books?id=nQ7RAAAAMAAJ.

[21] Transferring Wealth and Power from the Old to the New World: Monetary and Fiscal Institutions in the 17th Through the 19th Centuries (Michael D. Bordo & Roberto Cortés Conde, eds. 2006) at 436.

[22] John F. Due, Indirect Taxation in Developing Countries, Revised Edition (Johns Hopkins Press 1988) at 92-93.

[23] See Mikesell, supra note 2.

[24] Id.

[25] Id.

[26] Andrew Chamberlain & Patrick Fleenor, Tax Pyramiding: The Economic Consequences of Gross Receipts Taxes, Tax Foundation Special Report No. 147 (Dec. 4, 2006), https://taxfoundation.org/article/tax-pyramiding-economic-consequences-gross-receipts-taxes.

[27] Justin M. Ross, A Primer on State and Local Tax Policy: Trade-Offs Among Tax Instruments (Feb. 25, 2014), http://mercatus.org/publication/primer-state-and-local-tax-policy-trade-offs-among-tax-instruments.

[28] James Mirrlees & Peter Diamond, Optimal Taxation and Public Production I: Production Efficiency, 61 American Economic Review 8 (1971), https://www.aeaweb.org/aer/top20/61.1.8-27.pdf.

[29] William A. Testa & Richard H. Mattoon, Is There a Role for Gross Receipts Taxation?, 60 National Tax Journal 821 (2007), http://www.ntanet.org/NTJ/60/4/ntj-v60n04p821-40-there-role-for-gross.pdf.

[30] David Brunori, Virginia’s Gas Tax Reform, State Tax Notes, Jan. 21, 2013, http://services.taxanalysts.com/taxbase/magdailypdfs.nsf/PDFs/67ST0177.pdf/$file/67ST0177.pdf.

[31] Jonathan Oosting, Michigan governor 2014: Did Rick Snyder do what he said he’d do?, MLive, Oct. 22, 2014, http://www.mlive.com/lansing-news/index.ssf/2014/10/michigan_governor_2014_did_ric.html.

[32] See Chamberlain & Fleenor, supra note 26.

[33] Scott Drenkard & Joseph Henchman, 2015 State Business Tax Climate Index (Oct. 28, 2014), https://taxfoundation.org/article/2015-state-business-tax-climate-index.

[34] For a literature review on econometric studies on taxes and economic growth, see William McBride, What Is the Evidence on Taxes and Growth?, Tax Foundation Special Report No. 207 (Dec. 18, 2012), https://taxfoundation.org/article/what-evidence-taxes-and-growth.

[35] Beacon Hill Institute at Suffolk University, Tax Reform in Texas: Lowering Business Costs, Expanding the Economy (Nov. 2012).

[36] John Merrifield & Corey DeAngelis, Dynamic Scoring Analysis of Spending Restraint Alongside a Franchise Tax Repeal (forthcoming 2015) (draft on file with author).

[37] Merrifield & DeAngelis utilize upper and lower bounds found in Barry W. Poulson & Jules Gordon Kaplan, State Income Taxes and Economic Growth, 28 Cato Journal 53 (2008), http://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/cato-journal/2008/1/cj28n1-4.pdf.