Key Findings

-

An ideal tax code is one that is simple, transparent, neutral, and stable, but many states, including Nebraska, have certain taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. provisions that depart from these principles of sound tax policy.

-

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated economic fallout have shed light on structural deficiencies in states’ tax codes, including narrow-based sales taxes and taxes that penalize in-state investment.

-

States with modern, well-structured tax codes are expected to recover better from the current recession than states with outdated, poorly structured tax codes.

-

To promote short-term economic recovery and long-term economic growth, Nebraska policymakers ought to reexamine the uncompetitive and burdensome provisions that currently exist in Nebraska’s tax code and prioritize those areas for reform.

-

Any tax reform plan that is developed in Nebraska ought to prioritize lower corporate and individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. rates, more competitive treatment of in-state investment, and reduced property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services. burdens—reforms that can be paid for in part by modernization of the sales tax base.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has created immense fiscal challenges for individuals, businesses, and governments alike. Stay-at-home orders, business closures, and social distancing guidelines have severely impacted business income and activities, and, in turn, employment and personal income. As state policymakers look to the months and years ahead, much of the speed of the economic recovery depends on how much longer COVID-19 remains a significant public health threat. It is difficult for even public health experts to predict how long the pandemic will impact life as we know it, but even after the immediate public health crisis abates, the economic recovery is expected to take several years. As such, Nebraska policymakers have an important role to play in ensuring their state is in an ideal position for a smooth and speedy economic recovery, and tax policy is an important part of that conversation.

Across the country, states that entered the COVID-19 pandemic with modern, well-structured tax codes can be expected to fare better than states that rely heavily on antiquated or unduly burdensome taxes. In particular, narrow sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. bases, and taxes that penalize investment without regard for business profitability, are among the taxes that will most hinder economic recovery and growth. Amid the widespread economic uncertainty caused by the pandemic, a stable, modern, pro-growth tax code has never been more important. As Nebraska taxpayers do their best to adapt to ongoing global public health and economic challenges while setting their sights on a better future in a post-COVID-19 world, Nebraska policymakers have an important role to play in enacting tax policies that give struggling taxpayers the best possible opportunity to get back on their feet and regain productivity, employment, and growth.

If Nebraska policymakers prioritize reforming certain uncompetitive features of the state’s current tax code, those policy decisions will give Nebraska the competitive advantage of a smoother economic recovery while putting the state on a better path to achieve strong economic growth for years to come. Ultimately, tax reform can help Nebraska emerge from the COVID-19 crisis stronger, and more in-tune with the 21st century economy, than it was before the pandemic. The pages that follow explore the economic benefits of a well-structured tax code, the evidence that states with well-structured tax codes will fare better amid the current recessionA recession is a significant and sustained decline in the economy. Typically, a recession lasts longer than six months, but recovery from a recession can take a few years. , and the importance of tax policy changes in Nebraska that prioritize broader bases, lower rates, and more competitive treatment of in-state investment.

The Benefits of a Modern, Well-Structured Tax Code

One of the basic realities at play in our federalist system of government is that states compete with one another—both regionally and nationally—for business investment. When businesses make decisions on where to locate or expand operations, a variety of factors are taken into consideration, such as access to raw materials, infrastructural capabilities, and the suitability of the labor pool. However, a prospective business location can meet all these criteria and yet be passed over as a destination for investment if the state’s tax code is burdensome and uncompetitive compared to other potential locations.

Taxes matter to businesses, and there are numerous tax rate and base considerations that can either help or hurt a state’s economic competitiveness. For instance, high tax rates can create “sticker shock,” making certain states appear less attractive as destinations for business investment, regardless of whether actual tax burdens are comparable. Businesses typically only examine a few options in detail, and initial filtering is not always terribly sophisticated. Additionally, rates send a stronger message about the state’s commitment to competitiveness than do incentives that might someday be curtailed, or which would not be available to other parts of the business were operations to expand. Ultimately, if a state’s tax code contains outdated, overly complex, or nonneutral tax provisions that disproportionately impact certain business activities or industries, businesses need not look far to find a more hospitable tax environment elsewhere.

Just as there are many factors contributing to a state’s attractiveness as a destination for business investment, there are multiple factors contributing to the speed at which a state’s economy will grow, but taxes are a critical consideration in both respects. For example, states that pursue education or infrastructural improvements—both quite important—may have to wait years or decades before reaping the economic benefits of those actions, but changes to a state’s tax code can spur investment and growth both quickly and sustainably.[2]

When states make tax changes, they do not do so in a vacuum. Every tax policy change a state makes will impact the state’s competitive standing, favorably or unfavorably, compared to its immediate neighbors as well as national competitors. Because states are afforded significant discretion in designing their own tax codes, apples-to-apples comparisons between one state tax code and another are difficult. However, each state’s tax code can and should be evaluated for how well it aligns with certain widely agreed upon principles of sound tax policy like simplicity, transparency, neutrality, and stability.[3] An ideal tax code is one that is easy to administer, comply with, and enforce; clearly and plainly communicates how much a taxpayer owes and when; avoids favoring or disfavoring specific activities or industries; and is consistent and predictable so neither taxpayers nor governments are caught off guard by fluctuating tax burdens or volatile revenue streams.

Furthermore, an ideal tax code is one with broad bases and low rates. Broad-based taxes exemplify the principle of neutrality, as they avoid exemptions and carveouts that result in some activities or industries being treated more favorably than others. All else equal, the broader the tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. , the lower the tax rate can be, resulting in a more neutral tax code and reducing “sticker shock.” Broad-based taxes are appropriate because the purpose of the tax code is to generate revenue to fund public services, not to influence individual and business decision-making. The more neutral the tax base and the more competitive the rate, the more likely it will be that taxes will raise revenue for public services in an efficient manner, without unduly hindering growth-generating activities.

When it comes to funding government services, there are many ways to raise a dollar of revenue, but some taxes are more harmful to the economy than others. As such, policymakers should take into careful consideration the relative economic harm of different tax types when determining how best to fund state and local government operations. Among major state revenue sources, taxes on income are generally less desirable than taxes on consumption because income taxes discourage wealth creation, while sales taxes are intended to fall only on the portion of earnings that are spent.

In a comprehensive review of international econometric tax studies, Arnold et al. (2011) found that corporate income taxes, followed by individual income taxes, are among the most detrimental to economic growth, while consumption and property taxes are the least harmful to economic growth.[4] The economic literature on graduated-rate income taxes is particularly unfavorable.[5] The Arnold et al. study concluded that reductions in top marginal rates would be beneficial to long-term growth, and Mullen and Williams (1994) found that higher marginal tax rates reduce gross state product growth. This finding even adjusts for the overall tax burden of the state, lending weight to the idea that any state can benefit from a broader-based, lower-rate tax structure.[6]

Not only are income taxes more economically harmful than taxes on consumption, but they are also more volatile, fluctuating greatly from one year to the next. Heavy reliance on volatile revenue sources leaves states facing large surpluses in some years and substantial shortfalls in others. This not only jeopardizes a state’s ability to maintain a specified level of government services in good economic years and bad, but it also interferes with the state’s ability to plan for the future and make long-term spending commitments. A simple, transparent, neutral, and stable tax code is important at all times, but especially during economic contractions, as a well-structured tax code can help lessen the severity of a recession by expediting recovery and growth.

Amid COVID-19, Nebraska Can Improve its Economic Outlook by Enacting Structural Tax Reform

The COVID-19 pandemic emerged in the United States with little warning and has put all states under a great deal of unexpected fiscal strain. Stay-at-home orders, business closures, social distancing guidelines, and similar policies have been widely deployed to mitigate the spread of the virus, but these measures carry significant economic costs, with personal consumption, business income, employment, and personal income all taking a hit and thereby impacting income and sales tax revenues. All states are facing financial challenges induced by the pandemic, but states that have taken steps to modernize their tax codes—and minimize the economic impact of the taxes they do levy—can be expected to recover more quickly than states that have unduly burdensome tax structures. As such, Nebraska policymakers should prioritize enacting pro-growth structural tax reforms now—when taxpayers and the economy need it most—rather than waiting to enact such reforms until years down the road.

Nebraska’s Property Tax System is Considered Burdensome and in Need of Reform

In Nebraska, property taxes have been a source of widespread frustration for years. Nebraska’s property tax collections—at $1,957 per capita—are higher than the national average of $1,617 per capita. When real property taxes are taken as a percentage of total home value, Nebraska has an effective property tax rate of 1.65 percent, the eighth highest effective rate in the nation.[7] Absent legislative action, these trends are unlikely to reverse soon, as property valuations continue to rise at a faster rate in Nebraska than in most of the rest of the country, heavily impacting farmers, homeowners, and business owners alike.

While taxes on real property—like land, buildings, and structures—receive most of the political attention, property taxes are also applied to certain kinds of tangible personal property (TPP)—or property that can be touched and moved—like agricultural and business machinery and equipment, trade fixtures, and certain types of business-owned software. Tangible personal property taxes are particularly harmful, as they discourage capital accumulation in the state of Nebraska, lead to economic distortions, and fall on businesses non-neutrally and without regard for business profitability.

Nebraska’s taxes on both real and tangible personal property are in need of reform, but it is important that policymakers get the details right and tackle property tax reform in a manner that provides sustainable, long-term relief. Recent proposals have sought to increase state aid to schools while reducing school district property tax assessment ratios. While this would reduce school district-levied property tax collections in the short term, it would make the state responsible for a greater share of school funding, which would put upward pressure on state income and sales tax rates over time. Increased state involvement in school funding can also erode local decision-making authority.

During the 2020 legislative session, legislators passed and Gov. Pete Ricketts (R) signed LB1107, legislation that sets a $275 million statutory minimum allocation to the Property Tax Credit Cash Fund and creates a new refundable income tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. to help offset the local school district property tax burdens taxpayers face. With the adoption of this legislation, the state has promised to offset a growing share of local school district property tax burdens over time but has done so without specifying where most of this revenue will come from. The new law also stops short of establishing any additional constraints on rising property valuations. As such, the new law will not prevent local property taxes from rising; it will merely provide additional state resources to subsidize a greater share of rising local property taxes.

Too often, state efforts to reduce property taxes through tax swaps have resulted in state-level tax increases without appreciably lowering property tax burdens, or with reductions only lasting a few years.[8] Moving forward, Nebraskans deserve a better and more comprehensive approach, in which any shifting of tax burdens away from property taxes is combined with more effective measures to keep the future growth of property taxes in check. In addition, state policymakers should consider strengthening existing laws that require public notice and a public hearing before local political subdivisions accept an increase in property tax revenue from one year to the next. Property tax reform is not easily achieved in a vacuum, however, so these policy goals would best be accomplished as part of a broader, comprehensive tax reform package that also reexamines certain aspects of state income and sales taxes.

Nebraska’s Individual Income Tax Rates Are High Compared to Neighboring States

Nebraska’s high property tax burdens are just one of the tax-related factors hindering the state’s economic competitiveness. Nebraska’s high income tax rates are another factor that detrimentally impacts the state’s competitive standing when it comes to individual and business location decisions.

One way of comparing individual income taxes among states is to consider the effective income tax rate at various levels of taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. . Table 1 shows income tax liability for a single filer with various levels of taxable income in Nebraska and each of its neighboring states. This illustration assumes a single filer with no dependents, and any applicable standard deduction and personal exemption (or personal exemption credit) is applied.

| 2020 Income Tax Liability at Different Levels of Taxable Income, Nebraska and Neighboring States (Single Filer) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | $30,000 | $75,000 | $150,000 | $250,000 |

|

Nebraska |

$682 | $3,600 | $8,730 | $15,570 |

|

Colorado |

$815 | $2,898 | $6,371 | $11,001 |

|

Iowa |

$1,018 | $3,490 | $8,264 | $14,163 |

|

Kansas |

$977 | $3,518 | $7,793 | $13,493 |

|

Missouri |

$738 | $3,117 | $7,244 | $12,644 |

|

South Dakota |

$0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

|

Wyoming |

$0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| Note: Assumes single filer claiming standard deduction and one personal exemption, where applicable. Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri’s calculations do not include local income taxes, which can be substantial. | ||||

| Source: Author’s calculations. | ||||

For a taxpayer with $30,000 in taxable income, the effective tax rate in Nebraska is lower than the effective rate in each of Nebraska’s neighboring states (except for those states without an individual income tax). But for taxpayers with $75,000, $150,000, or $250,000 in taxable income, Nebraska’s effective income tax rate is higher than the effective rate in every neighboring state. (It is also worth noting that, subject to revenue availability, Iowa’s income taxes are scheduled to be reduced starting in 2023, when the state’s nine brackets will be consolidated into four, and the top rate will drop to 6.5 percent.)[9]

It is important to keep in mind that individual income taxes are paid by individuals and families, as well as by businesses that are structured as pass-throughs (including sole proprietorships, partnerships, limited liability companies, and S corporations). Since many owners of pass-through businesses have income exposed to the top state individual income tax rate, this rate greatly impacts the state’s economic competitiveness and attractiveness to businesses. To improve the state’s economic competitiveness both regionally and nationally, Nebraska should prioritize reducing its top marginal individual income tax rate.

States with Lower Individual Income Tax Rates Are More Likely to Experience Net In-Migration

While the current recession is unique in that business closures, stay-at-home orders, and social distancing measures have significantly impacted sales tax collections in the short term, many public finance experts predict income tax revenues will ultimately take a larger and longer-term hit, as it may take years for employment, wages, and business and personal income to be restored to pre-pandemic levels.[10] In general, reliance on traditionally more stable sources of revenue, like the sales tax, instead of more volatile sources of revenue, like income taxes, enhances revenue stability. In turn, revenue stability can mitigate the need for steep budget cuts and tax increases during recessions and subsequent recoveries.

As previously noted, higher top individual income tax rates—and graduated-rate income tax structures—are associated with lower levels of economic growth. In addition, high income tax rates are associated with state net out-migration.

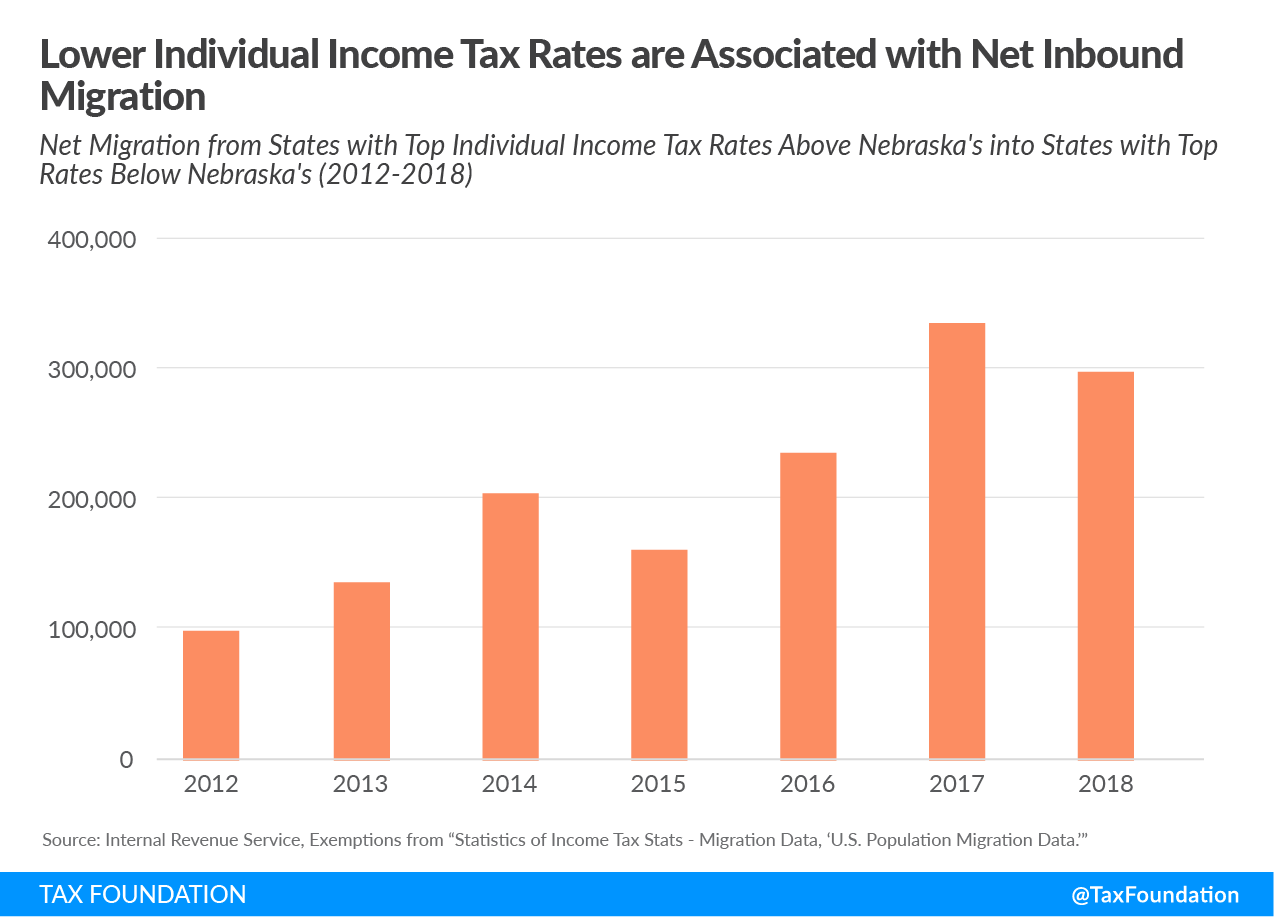

One way to measure interstate migration is to compare the movement of federal individual income tax returns and the corresponding exemptions (people) between states over time. Using Internal Revenue Service (IRS) migration data, Figure 1 shows annual net migration into states with a top marginal individual income tax rate above and below Nebraska’s 6.84 percent rate. States see migration from other states and from abroad, but here we focus on state-to-state migration trends. In the aggregate, states with a top marginal individual income tax rate below Nebraska’s saw net in-migration each year between 2012 and 2018, for a total net gain of more than 1.47 million residents during those seven years, with identical outflows of residents from states with higher rates.

Figure 1.

There are many reasons an individual or family might move from one state to another, whether for a job or educational opportunities, for family reasons, for quality of life, or otherwise. While taxes are not often the primary reason individuals move, cost-of-living considerations—including tax burdens—factor into many people’s relocation decisions.

Tax burdens impact migration in two key ways. First, some individuals and businesses move in search of more competitive tax rates, and this is especially true of higher net-worth individuals. Second, because many people’s interstate moves are driven by new job opportunities, individuals will move where jobs are prevalent. As such, business location decisions—which can be heavily influenced by tax considerations—are a significant driver of individuals’ location decisions.

While there are many ways to measure a state’s fiscal health, states that enjoy steady in-migration are more likely to experience economic growth than those that struggle to attract and retain businesses and residents. States with well-structured tax codes are better able to attract new businesses, facilitate new employment opportunities, and generate economic growth, so policymakers should always be on the lookout for ways to improve and modernize their tax code. A simple, stable, modern, pro-growth tax code is a valuable competitive advantage for any state, but it can be of particular benefit to states in the Great Plains region that, however unfairly, might struggle to attract businesses and residents due to certain geographic biases.

Individuals and businesses care about many things when making location decisions, but taxes are an important part of the equation, and they are a factor that is within policymakers’ control. States with well-structured tax codes and lower top marginal individual income tax rates are already enjoying the economic benefits of net in-migration, but states like Nebraska that face a fairly consistent net out-migration problem can become more competitive in a post-COVID-19 world by reducing income tax rates and burdens.[11] Furthermore, as this pandemic has profoundly disrupted lives and livelihoods all across the country, many individuals and families are reconsidering their financial and geographic decisions, and many workplaces are offering greater flexibility for their employees to work remotely from out-of-state.[12] Looking ahead to the future, Nebraska can take advantage of these economic disruptions by taking steps to make the state more attractive as a destination to live, work, and grow a business, perhaps attracting many new residents from out-of-state and reversing the pattern of net out-migration from Nebraska. Tax modernization would help Nebraska become an appealing alternative compared to many high-tax states, especially those that are further increasing taxes on their residents and employers amid the pandemic.

Nebraska’s Corporate Income Tax Rate Is the Highest in the Great Plains Region

Consistent with its high taxes on personal and pass-through businessA pass-through business is a sole proprietorship, partnership, or S corporation that is not subject to the corporate income tax; instead, this business reports its income on the individual income tax returns of the owners and is taxed at individual income tax rates. income, Nebraska also imposes high tax rates on corporate income. Among the 44 states with a corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. , Nebraska is one of just 14 that uses a graduated-rate structure.[13] With a top rate of 7.81 percent, Nebraska’s corporate income tax rate is the highest in the Great Plains region. Two of Nebraska’s immediate neighbors—South Dakota and Wyoming—forgo corporate income taxes altogether, and among nearby states, only Iowa and Minnesota have higher corporate income tax rates.

Nebraska’s high corporate income tax rate hinders the state’s economic competitiveness, which is one of the reasons the state has found itself relying heavily on business tax incentives in an effort to attract businesses to the state. While these incentives offset some of the burden of Nebraska’s high corporate income tax rate, a more neutral, sustainable, growth-inducing approach would be to reduce the corporate income tax rate. Nebraska’s corporate income tax accounted for just over $264 million—or 3.8 percent of the state’s own-source revenue—in fiscal year 2017, but as with the individual income tax, a high rate can cause “sticker shock” that deters potential investors.

In a report examining the effects of corporate income taxes on the location of foreign direct investment in U.S. states, Agostini and Tulayasathien (2001) found that “[for] foreign investors, the corporate tax rate is the most relevant tax in their investment decision.” Therefore, they found that foreign direct investment was quite sensitive to states’ corporate tax rates.[14] Harden and Hoyt (2002) conclude that among the taxes levied by state and local governments, the corporate income tax has the most significant negative impact on the rate of growth in employment.[15]

The corporate income tax falls on both capital and labor, and disincentivizes capital investment. Reducing reliance on the corporate income tax would help Nebraska better compete for business investment both regionally and nationally.

Nebraska’s Taxation of International Income Makes the State an Outlier

As a byproduct of Nebraska’s conformity with certain changes to the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) that were enacted by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the Nebraska Department of Revenue has determined the state automatically taxes certain Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI). At the federal level, GILTI is one of two guardrails, along with the Base Erosion Anti-Abuse Tax (BEAT), which can return some international income to the federal tax base despite the broader transition from a global to a territorial tax regime. In other words, the federal government is moving away from the taxation of international income, with certain exceptions, whereas Nebraska, which has not historically taxed international income, is conforming to those exceptions to do so for the first time.

The federal GILTI inclusion functions in tandem with other provisions Nebraska lacks, like the credit for foreign taxes paid. Consequently, not only does conformity to GILTI involve state taxation of international income, but it yields a far more aggressive international tax regiment than the one implemented by the federal government. Moreover, its purpose—to discourage profit shifting by parking intangible property in low-tax jurisdictions overseas—is not served by inclusion in state tax codes.

States were never meant to tax international income, and doing so injects great complexity into Nebraska’s tax code while raising serious constitutional issues that may have to be resolved in court. Nebraska’s taxation of GILTI penalizes multinational businesses for locating in Nebraska, as those businesses would not face similar taxation of international income were they to domicile in another state. As such, Nebraska’s taxation of GILTI discourages in-state investment and makes Nebraska less attractive compared to states that avoid taxing international income, including several of Nebraska’s immediate neighbors. Fully eliminating any taxation of international income should be a top tax policy priority for Nebraska policymakers. Of all the ways to generate revenue to fund government services, state taxation of international income is particularly harmful to the state’s economy and ought to be avoided, especially during the current recession.

Broad-Based Sales Taxes Improve Revenue Stability and Can Help Pay for Pro-Growth Reforms

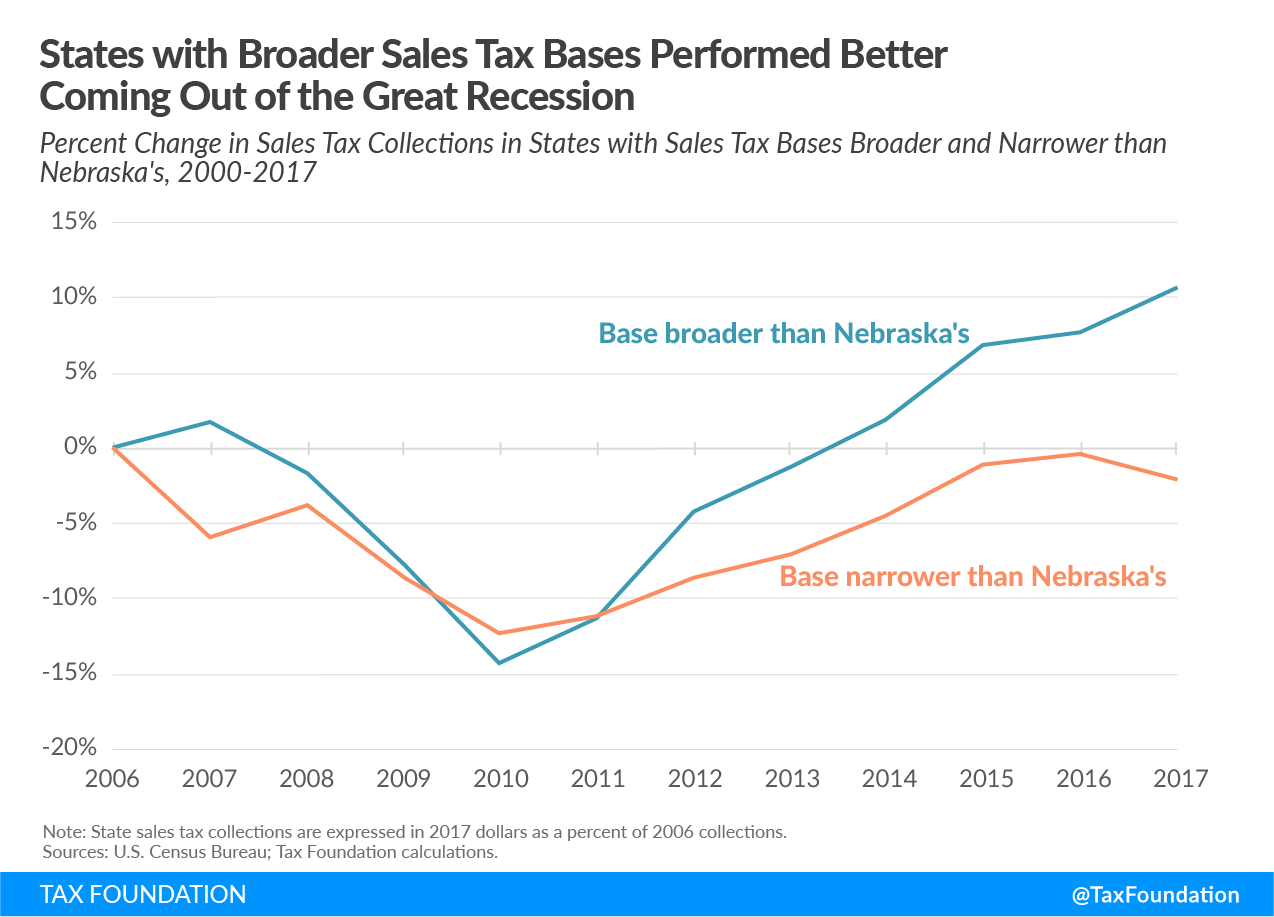

One of the key features of a well-structured state tax code is a sales tax that applies broadly to most, if not all, final personal consumption while avoiding the taxation of business inputs to prevent tax pyramidingTax pyramiding occurs when the same final good or service is taxed multiple times along the production process. This yields vastly different effective tax rates depending on the length of the supply chain and disproportionately harms low-margin firms. Gross receipts taxes are a prime example of tax pyramiding in action. .[16] Most sales tax bases are far narrower than economists would recommend, but states with broader sales tax bases enjoy greater sales tax revenue stability and growth—both during recessions and in the long-term—than states that exempt many final consumer transactions.

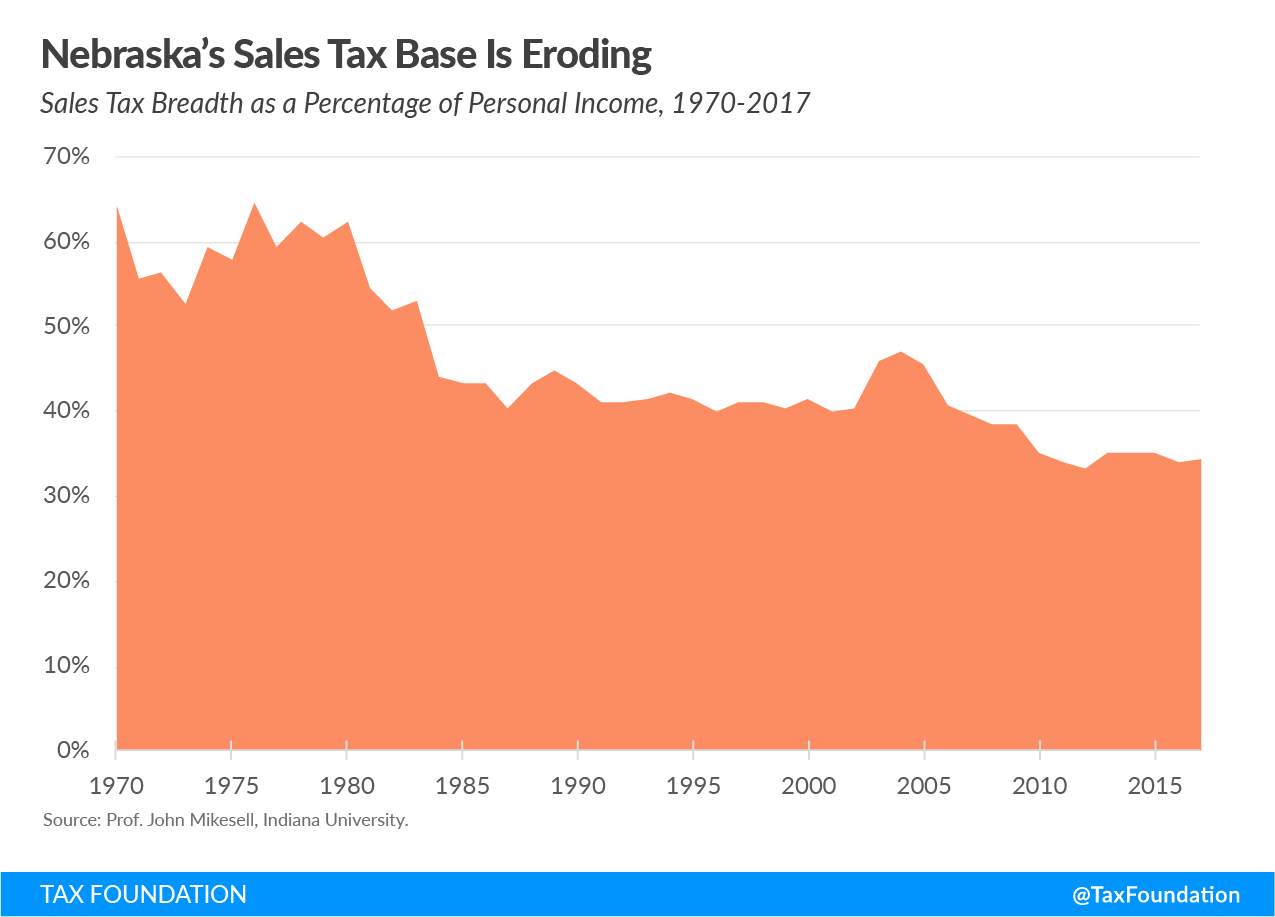

Apples-to-apples comparisons of state sales tax bases are difficult, but one method of approximating sales tax breadth is to calculate the value of taxed transactions as a percentage of personal income. Nebraska, like most states, exposes some transactions to multiple levels of taxation while omitting others altogether. Nebraska’s sales tax breadth, at 34 percent of state income in fiscal year 2017, is below the median; 26 states have sales tax bases that are broader than Nebraska’s. A robust sales tax base would not reach 100 percent of personal income, as not all income is consumed in any given year, but a tax on all final consumption tends to have a value equal to approximately three-quarters of personal income.

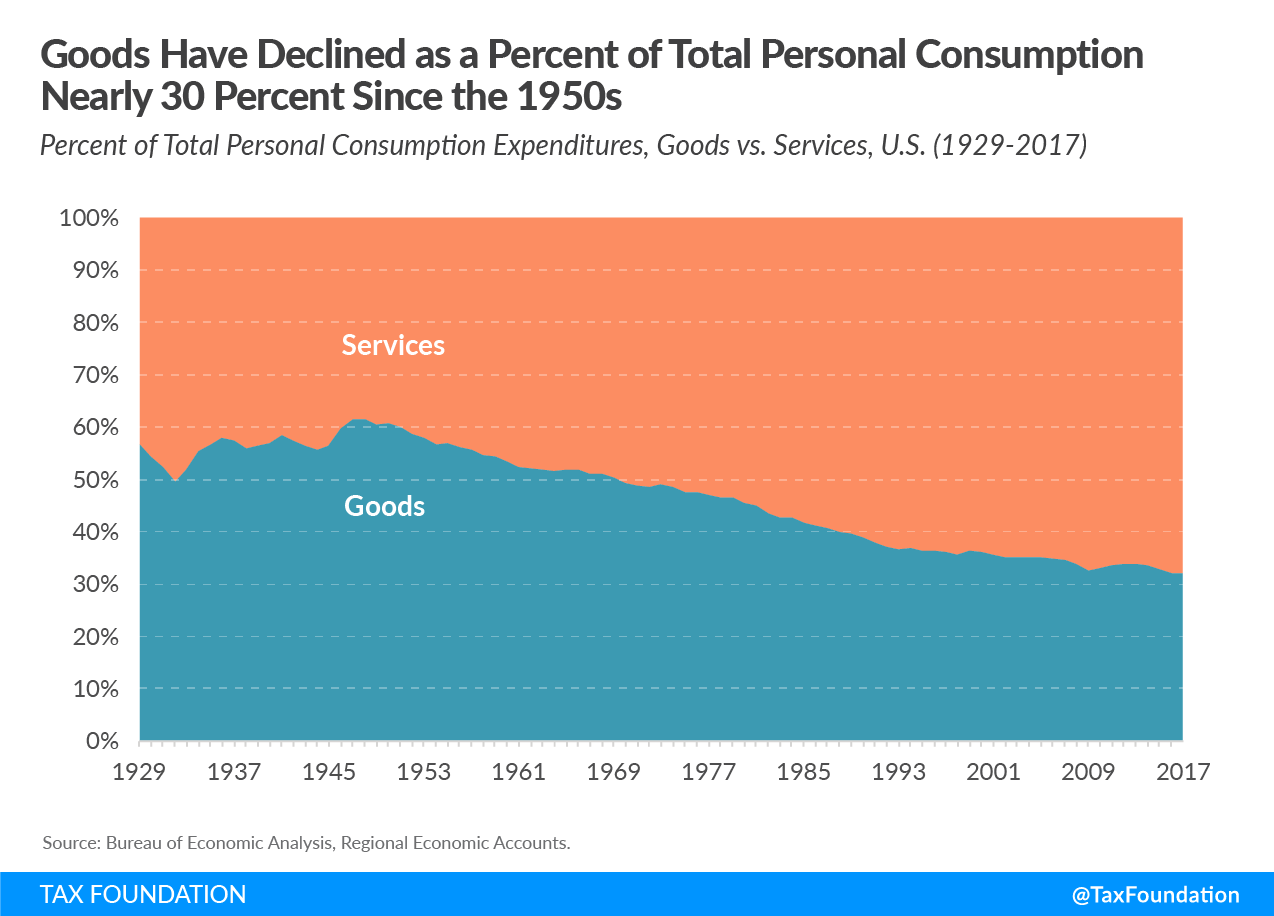

Much of Nebraska’s narrow sales tax base stems from its application to relatively few consumer services. Services comprise a much larger share of personal consumption now than they did it 1967, when Nebraska’s sales tax was first adopted (see Figure 2). The trend toward a more service-oriented economy, combined with pressure to exempt certain goods that were originally subject to the tax, has resulted in the erosion of the sales tax base over time. As shown in Figure 3, Nebraska’s sales tax originally applied to a base representing approximately 64 percent of personal income in the state. Over the past five decades, the sales tax has eroded to just more than half its original breadth.

If the base continues to shrink as a share of total consumption, lawmakers are likely to have to continue resorting to tax rate increases over time to make up for lost revenue. Modernizing the sales tax base is a better option, as it would make the sales tax more neutral while yielding additional state and local revenue that can be used to reduce reliance on other, more economically harmful or burdensome state and local taxes.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

In broadening the sales tax base, Nebraska policymakers should take care to avoid newly applying the sales tax to goods or services that are primarily purchased as business inputs. By definition, consumption taxes ought to apply to final consumer transactions, not intermediate transactions. When business inputs are exposed to the sales tax, those taxes get embedded in the price of the final good or service multiple times over in a nontransparent manner. This increases the costs of production, with much of the tax burden ultimately borne by consumers in the form of higher prices.

When a sales tax exposes many business inputs to taxation, the sales tax ends up functioning more like a gross receipts taxGross receipts taxes are applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like compensation, costs of goods sold, and overhead costs. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and applies to transactions at every stage of the production process, leading to tax pyramiding. , which is among the most economically harmful taxes states currently levy. The taxation of business inputs inevitably impacts some businesses and industries more heavily than others depending on how heavily a business consumes taxable products and services. Severe cases of tax pyramiding can distort business decision making, encouraging some firms to integrate vertically to avoid intermediate-level sales taxes, for example, when maintaining two separate firms might otherwise be the most economically efficient decision.

While no state hews perfectly to the ideal of avoiding the taxation of business inputs altogether, states should take care to avoid worsening the tax pyramiding that is already occurring. One recent study estimated that approximately 44 percent of Nebraska’s state and local sales taxes are paid by businesses. Again, much of the burden of these taxes gets passed along to consumers, but the sales tax incidence on businesses in Nebraska is higher than in many other states, so Nebraska policymakers should keep this in mind when pursuing sales tax base modernization.

All state sales tax bases tax some intermediate transactions while exempting some final consumption. In prioritizing ways to “right-size” the sales tax base, policymakers should seek to exempt the currently taxed inputs that are most prone to pyramiding (those that are likely to be taxed several times over) and which fall on the most mobile aspects of production (those most easily shifted to other states to avoid taxation). Intermediate goods that are consumed in the production process are the most counterproductive to tax. Meanwhile, consumer goods and services that tend to be purchased disproportionately by higher net worth individuals, but which are currently exempt from the sale tax, may be the most attractive place to start in sales tax base broadening.

Figure 4 shows how state sales tax revenue fared during and after the Great Recession in states with sales tax bases that are broader and narrower than Nebraska’s, respectively. While all states suffered revenue losses during the Great Recession, states with broader sales tax base saw considerably greater growth coming out of the crisis. The chart below shows how states with sales tax bases broader than Nebraska’s compare to those with narrower bases.

Figure 4.

In and of itself, right-sizing the sales tax base is a valuable reform to consider, as it would reverse the base erosion that has occurred over time, generating additional revenue while improving the neutrality of Nebraska’s tax structure. But sales tax base broadeningBase broadening is the expansion of the amount of economic activity subject to tax, usually by eliminating exemptions, exclusions, deductions, credits, and other preferences. Narrow tax bases are non-neutral, favoring one product or industry over another, and can undermine revenue stability. can also be the key to reducing other, more harmful and burdensome taxes. As policymakers looks for ways to lessen the severity of the current recession and promote a stronger recovery, sales tax base modernization can help “pay for” pro-growth reforms that would yield long-term benefits to the state—including the aforementioned reforms—while minimizing economic harm compared to many alternative revenue-positive tax changes.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated economic fallout have created unprecedented challenges for businesses and families. Unemployment is high, and much uncertainty remains with respect to how much longer the immediate public health crisis will impact life as we know it. While much of the speed of the economic recovery depends on the speed with which effective public health interventions become widely available, state policymakers are in a unique position to make policy decisions that will either help or hinder their state’s economic recovery.

States with a modern, well-structured tax code entered the current economic contraction in a better fiscal position, and can be expected to recover more quickly, than states with unduly complex and burdensome tax codes. Nevertheless, states that entered the pandemic with a less-competitive tax code can employ tax reform as a critical tool to aid their economic recovery and ultimately emerge from this crisis in a more competitive standing than when they entered it. As Nebraska policymakers consider policies to aid the state’s economic recovery, the benefits of a well-structured tax code should be at the forefront of policymakers’ minds. In particular, Nebraska policymakers should prioritize reducing corporate and individual income tax rates, reducing reliance on taxes that discourage in-state investment, and reducing the property tax burden—priorities that can be accomplished in part by broadening the sales tax base. A competitive tax code has never been more important, and these tax policy improvements can both strengthen the short-term economic recovery and promote long-term economic growth in Nebraska.

[1] The author would like to thank Maxwell James for his research contributions.

[2] Jared Walczak, 2020 State Business Tax Climate Index, Tax Foundation, Oct. 22, 2019, 8, https://taxfoundation.org/publications/state-business-tax-climate-index/.

[3] “Principles of Sound Tax Policy,” Tax Foundation, https://taxfoundation.org/principles/.

[4] Jens Arnold, Bert Brys, Christopher Heady, Åsa Johannsson, Cyrille Schwellnus, and Laura Vartia, “Tax Policy for Economic Recovery and Growth,” The Economic Journal 121:550 (February 2011).

[5] See William McBride, “What is the Evidence on Taxes and Growth?” Tax Foundation, Dec. 18, 2012, https://taxfoundation.org/what-evidence-taxes-and-growth.

[6] John K. Mullen and Martin Williams, “Marginal Tax Rates and State Economic Growth,” Regional Science and Urban Economics 24:6 (December 1994).

[7] Katherine Loughead, “Will Nebraska Find a Path Forward in its Property Tax Standstill?” Tax Foundation, Mar. 10, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/nebraska-property-tax-reform/.

[8] Jared Walczak, “Why State-for-Local Tax Swaps Are So Hard to Do,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 18, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/state-for-local-tax-swaps/.

[9] Jared Walczak, “What’s in the Iowa Tax Reform Package,” Tax Foundation, May 9, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/whats-iowa-tax-reform-package/.

[10] Jared Walczak, “State Forecasts Indicate $121 Billion 2-Year Tax Revenue Losses Compared to FY 2019,” Tax Foundation, July 15, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/state-revenue-forecasts-state-tax-revenue-loss-2020/.

[11] Joseph Henchman and Scott Drenkard, “Building on Success: A Guide to Fair, Simple, Pro-Growth Tax Reform for Nebraska,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 3, 2013, 10, https://taxfoundation.org/building-success-guide-fair-simple-pro-growth-tax-reform-nebraska/.

[12] See Catherine E. Shoichet and Athena Jones, “Coronavirus is Making Some People Rethink Where They Want to Live,” CNN, May 2, 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/05/02/us/cities-population-coronavirus/index.html.

[13] Janelle Cammenga, “State Corporate Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2020,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 28, 2020, /wp-content/uploads/2020/01/State-Corporate-Income-Tax-Rates-and-Brackets-for-20201.pdf.

[14] Claudio Agostini and Soraphol Tulayasathien, “Tax Effects on Investment Location: Evidence for Foreign Direct Investment in the United States,” Office of Tax Policy Research, University of Michigan Business School (2001).

[15] J. William Harden and William H. Hoyt, “Do States Choose their Mix of Taxes to Minimize Employment Losses?” National Tax Journal 56 (March 2003): 7-26.

[16] Nicole Kaeding, “Sales Tax Base Broadening: Right-Sizing a State Sales Tax,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 24, 2017, 12, https://taxfoundation.org/sales-tax-base-broadening/.

Share this article