Key Findings

- The House and Senate Republicans of the 115th Congress and the Trump Administration have put forth a number of important goals for taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. reform: economic growth, simplicity, lower marginal tax rates on individuals and businesses, and a broader tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. .

- The Tax Foundation has put together four illustrative tax plans that demonstrate ways in which lawmakers could accomplish their goals while keeping the level of federal revenue as a percent of GDP and the distribution of the tax burden roughly the same as current law.

- Option A focuses on removing the bias against investment from the federal tax code by converting the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. into a 22.5 percent cash flow tax, which would allow for full expensingFull expensing allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of certain investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings. It alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. of investments. This plan would increase the long run level of GDP by 7.1 percent. The plan is based on the House GOP Blueprint, but with a few alterations.

- Option B would scale down the current income tax system and replace the revenue with a broad-based, low-rate consumption taxA consumption tax is typically levied on the purchase of goods or services and is paid directly or indirectly by the consumer in the form of retail sales taxes, excise taxes, tariffs, value-added taxes (VAT), or income taxes where all savings are tax-deductible. , all while making the tax code more progressive than current law. We estimate this plan would increase the long run level of GDP by 3.2 percent.

- Option C follows the basic contours of the current tax system but makes improvements to both the individual income and corporate income tax codes.

- Option D would substantially lower business tax rates, in addition to other improvements to the income tax system, and would lead to lower federal revenue in the long run and would require spending offsets.

- All four of these plans were modeled assuming that all policies were permanent. However, it is possible that lawmakers opt to make all or some of a tax plan temporary in order to navigate budget rules. Lawmakers should be cautious of using temporary policy.

- We modeled all of these tax plans looking at their impact on revenue after all policies have fully phased in. Many of these plans, though, could potentially impact revenue over the budget window in different ways depending on how they are structured.

- For this analysis we did not include dynamic revenue estimates, as we limited our analysis to tax reform plans that would be deficit-neutral on a conventional basis. However, we estimated that all of these plans would improve the tax code and boost the long-run size of the economy, which would provide additional revenue

Introduction

House and Senate Republicans of the 115th Congress and the Trump Administration have put forth several important goals for tax reform in recent months. Their priorities include improving the economic efficiency of the tax code by reducing marginal tax rates and by broadening the tax base, as well as creating a simpler the tax code that eliminates many of the complex features of the current system. In addition, the Trump Administration has also said that tax reform should provide middle class tax relief and not provide a tax cut for top earners. Finally, many lawmakers have expressed a sense that any reforms to the federal tax code should be permanent.

In addition to these general goals, lawmakers and the administration have floated a number of specific policy objectives. Congressional Republicans and the administration would like to cut the corporate income tax rate to a globally competitive level while speeding up cost recoveryCost recovery refers to how the tax system permits businesses to recover the cost of investments through depreciation or amortization. Depreciation and amortization deductions affect taxable income, effective tax rates, and investment decisions. . Lawmakers have also put forth plans to reduce individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. rates, expand the standard deduction, eliminate the Alternative Minimum Tax, and eliminate the estate tax, among other changes.

Many of these proposals are promising, and would represent an improvement over the current system. There are a variety of ways that lawmakers could accomplish these goals through a tax reform bill, but regardless of the approach, lawmakers will need to make tough choices. For instance, lawmakers will have to figure out how to accomplish their goals in a fiscally sustainable manner, due to the Byrd Rule, which requires that reconciliation bills not add to the federal deficit in the long run.

We have put together four illustrative tax plans to demonstrate ways in which lawmakers could enact tax reform that accomplishes the GOP’s goals while keeping the federal deficit and the distribution of the federal tax burden roughly constant.

Overview

All four of the illustrative plans assembled by the Tax Foundation accomplish all or some of the goals set forth by the administration and Congressional Republicans. All four plans are pro-growth: they all improve the structure of the tax code in a way that promotes economic efficiency, and they would all boost the long-run size of the economy, leading to higher wages and living standards.

Three of the four plans are revenue-neutral on a static basis. When fully phased-in, Options A, B and C would raise roughly the same amount of revenue as the current tax code, without factoring in any macroeconomic effects. Option D relaxes the revenue neutrality constraint and would require spending cuts of about $75 billion on an annual basis when fully phased in, in order to remain deficit-neutral in the long run.

These plans are not necessarily what Tax Foundation believes are the “ideal” tax reform plans. Rather, they are meant to illustrate that there a number of ways that congressional leaders and the Administration could achieve many of their tax reform goals while keeping static federal revenue and the distribution of the tax burden roughly the same as current law.

Perhaps most importantly, these plans also demonstrate that lawmakers, taxpayers, and business groups will need to make a number of tradeoffs in order to get a better overall tax code. None of these plans contains all the priorities of every group. And these plans make tough choices by eliminating deductions and credits in order to reduce statutory tax rates.

| Option A | Option B | Option C | Option D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Long-run Change in GDP |

7.1% | 3.2% | 2.4% | 3.7% |

|

Long-run change in Wages |

5.3% | 3.0% | 1.6% | 2.7% |

|

Long-run Static Revenue Change |

Revenue Neutral | Revenue Neutral | Revenue Neutral | $75 billion annual tax cut |

|

Long-run Static Distributional Impact, Percent Change in After-Tax Income by Income Group |

||||

|

0% to 20% |

0.4% | 1.5% | 0.8% | 1.0% |

|

20% to 40% |

0.4% | 1.4% | 0.8% | 1.0% |

|

40% to 60% |

0.1% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.4% |

|

60% to 80% |

0.3% | 0.1% | 0.5% | 0.6% |

|

80% to 100% |

0.0% | -0.4% | -0.3% | 0.8% |

|

80% to 90% |

0.5% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.3% |

|

90% to 95% |

0.3% | 0.7% | -0.5% | -0.3% |

|

95% to 99% |

0.1% | 0.1% | -0.4% | 0.0% |

|

99% to 100% |

-0.8% | -1.8% | -0.5% | 2.6% |

Option A

Option A focuses on removing the bias against investment from the federal tax code, by converting the corporate income tax into a 22.5 percent cash flow tax, which would allow for full expensing of investments. The plan is based on the House GOP Blueprint, but with a few alterations.

This plan produces the largest increase in long-run GDP of the four tax plans. We estimate it would increase the long-run level of GDP by 7.1 percent (this is equal to about a 0.7 percent increase in the growth rate each year, for a decade). This plan would provide a modest tax cut for taxpayers in the bottom 99 percent of taxpayers (a tax cut of between 0.1 percent and 0.5 percent of income). At the same time, the top 1 percent would face a slightly higher tax burden of about 0.8 percent of their after-tax incomeAfter-tax income is the net amount of income available to invest, save, or consume after federal, state, and withholding taxes have been applied—your disposable income. Companies and, to a lesser extent, individuals, make economic decisions in light of how they can best maximize their earnings. . Overall, however, the plan would not significantly change the distribution of the federal tax burden.

Option A accomplishes significant economic growth primarily by converting the corporate income tax into a 22.5 percent cash flow tax. The most important element of this shift is full expensing: all businesses would be able to fully expense, or deduct, all capital investment in the year in which it is put into service. In addition, non-financial businesses would no longer be able to deduct net interest expense (they would, however, be able to deduct interest expense against interest income). Unlike previous iterations of the GOP Blueprint, this cash flow tax would be an “source-based” cash flow tax, meaning it does not have a border adjustment provision. The plan would enact a territorial tax systemTerritorial taxation is a system that excludes foreign earnings from a country’s domestic tax base. This is common throughout the world and is the opposite of worldwide taxation, where foreign earnings are included in the domestic tax base. , by providing a 95 percent deduction for dividends received. The plan would also eliminate several non-structural business tax expenditures.[1]

In the individual income tax, this plan would consolidate the seven current tax brackets into three rates of 12 percent, 20.5 percent, and 37 percent. The standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. Taxpayers who take the standard deduction cannot also itemize their deductions; it serves as an alternative. would be nearly doubled, from $6,350 ($12,700 married filing jointly) to $12,000 ($24,000 married filing jointly). Both the alternative minimum tax and the Pease limitation on itemized deduction would be eliminated.

These changes would be offset by eliminating all itemized deductions except for the home mortgage interest deduction and the charitable contribution deduction. The home mortgage interest deductionThe mortgage interest deduction is an itemized deduction for interest paid on home mortgages. It reduces households’ taxable incomes and, consequently, their total taxes paid. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) reduced the amount of principal and limited the types of loans that qualify for the deduction. would be capped at $500,000 of acquisition debt.

Family and child benefits would be consolidated. The personal exemption would be replaced with a $500 non-refundable credit for non-child dependents and. As such, the child tax credit would be expanded by increasing the credit to $1,500 (while only allowing $1,000 to be refundable). The child tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. would phase-out for married couples at twice the AGI threshold for singles and heads of household.

Capital gains and dividends would be taxed as ordinary income, but individuals would be able to deduct 40 percent of qualified dividends and long-term capital gains against taxable income. The tax burden on capital gains and dividends earned by individuals would increase slightly compared to current law. However, the overall burden on capital income (including the impact of the corporate tax) would fall.

Interest income, which would continue to be taxed as ordinary income, would also be provided a 40 percent deduction. This offsets the tax increase on debt financing at the entity level that occurs due to the elimination of the net interest expense deduction. The total tax burden on debt finance would fall even though it would be subject to two layers of tax.

The estate taxAn estate tax is imposed on the net value of an individual’s taxable estate, after any exclusions or credits, at the time of death. The tax is paid by the estate itself before assets are distributed to heirs. would be eliminated.

| Provision | Long-Run Annual Revenue Impact (Billions of 2017 Dollars) | Long-Run Annual Revenue Impact %GDP | Long-run Impact on GDP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eliminate the alternative minimum tax | -$35.00 | -0.2% | -0.3% |

| Consolidate individual income tax brackets into three rates, of 12 percent, 20.5 percent, and 37 percent | -$188.52 | -1.0% | 1.4% |

| Eliminate itemized deductions and the Pease limitation | $194.41 | 1.0% | -0.2% |

| Cap the home mortgage interest deduction | $30.60 | 0.2% | -0.1% |

| Increase the standard deduction to $12,000 ($24,000 married filing jointly; $18,000 head of household) | -$153.73 | -0.8% | 0.5% |

| Consolidate family benefits | $155.31 | 0.8% | -0.4% |

| Tax capital gains and dividends as ordinary income; Provide 40% deduction for interest, capital gains, and dividends | -$27.97 | -0.1% | -0.1% |

| Lower the corporate income tax rate to 22.5% | -$103.96 | -0.5% | 2.7% |

| Allow for full expensing of capital investments | -$63.68 | -0.3% | 2.9% |

| Eliminate deduction for net interest expense | $184.96 | 1.0% | -0.2% |

| Eliminate business tax expenditures | $48.97 | 0.3% | -0.1% |

| Move to a territorial tax system | -$18.10 | -0.1% | 0.0% |

| Eliminate the estate tax | -$27.79 | -0.1% | 1.0% |

| Total | -$4.49 | 0.0% | 7.1% |

Option B

Option B would scale down the current income tax system, while replacing the revenue with a broad-based, low-rate consumption tax.

This plan is based on Michael Graetz’s Tax Plan,[2] Senator Cardin’s (D-MD) “Progressive Consumption Tax,”[3] and Representative Jim Renacci’s (R-OH) “Simplifying America’s Tax System”[4] plan. This plan accomplishes many of the goals set forth by the administration: cutting taxes for middle-income taxpayers and reducing the corporate income tax rate to 15 percent, while keeping federal revenue constant. It also does not reduce the tax burden of the top 1 percent of income earners.

We estimate that Option B would grow the long-run size of the economy by 3.2 percent and increase wages by 3 percent. It would also increase the progressivity of the federal tax burden by reducing the tax burden on the bottom 90 percent of taxpayers by between 0.2 percent and 1.5 percent. The largest tax cut would go to the bottom quintile. The top 1 percent of taxpayers would face a higher tax burden than under current law.

This plan cuts the corporate income tax rate from the current 35 percent to 15 percent. The plan makes bonus depreciation permanent and broadens the corporate tax base by eliminating non-structural business tax expenditures.

On the individual side, the current seven tax bracketsA tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. would be consolidated into three rates of 10, 25, and 38 percent. The standard deduction would be greatly increased, from $6,350 to $50,000 for single filers (from $100,000 married filing jointly; $75,000 heads of household).

The personal exemption and all personal credits would be eliminated, including the current Child Tax Credit and the Earned Income Tax Credit. These benefits would be replaced with three new consolidated credits: a new work credit, a new child tax credit, and a new additional child tax credit. These credits are structured in the same way as Senator Ben Cardin’s rebates.[5]

The plan would tax all capital income (capital gains, dividends, and interest) as ordinary income. Most itemized deductions would be eliminated. The three largest itemized deductions would be retained: the state and local tax deduction, the home mortgage interest deduction, and the charitable contribution deduction.

The Net Investment Income Tax, the AMT, and the Pease limitation on itemized deductionItemized deductions allow individuals to subtract designated expenses from their taxable income and can be claimed in lieu of the standard deduction. Itemized deductions include those for state and local taxes, charitable contributions, and mortgage interest. An estimated 13.7 percent of filers itemized in 2019, most being high-income taxpayers. would be eliminated.

To fund all of these cuts to the current tax system, Option B would enact a 13 percent, broad-based value-added tax.[6] This tax would conform to World Trade Organization standards by including imports and excluding exports.

| Provision | Long-Run Annual Revenue Impact (Billions of 2017 Dollars) | Long-Run Annual Revenue Impact %GDP | Long-run Impact on GDP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eliminate the alternative minimum tax | -$35.54 | -0.2% | -0.3% |

| Consolidate individual income tax brackets into three rates, of 10 percent, 25 percent, and 38 percent | -$303.15 | -1.6% | 1.7% |

| Eliminate all itemized deductions except for the state and local tax deduction, the charitable contribution deduction, and the home mortgage interest deduction; eliminate the Pease limitation | $27.62 | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Increase the standard deduction to $50,000 ($100,000 MFJ; $75,000 HOH); eliminate the personal exemption | -$593.40 | -3.1% | 2.9% |

| Replace all personal credits with simplified and consolidated work and child credits | -$122.50 | -0.6% | -0.5% |

| Eliminate the Net Investment Income Tax and tax capital gains and dividends as ordinary income | $70.49 | 0.4% | -0.8% |

| Lower the corporate income tax rate to 15 percent | -$166.34 | -0.9% | 4.1% |

| Permanently extend bonus depreciation | -$9.63 | 0.0% | 0.4% |

| Eliminate business tax expenditures | $32.88 | 0.2% | -0.04% |

| Enact a 13 percent value-added tax | $1,110.06 | 5.8% | -4.4% |

| Total | $10.49 | 0.1% | 3.2% |

Option C

Option C follows the basic contours of the current tax system but makes improvements to both the individual income and corporate income tax codes.

We estimate that Option C would increase the long-run level of GDP by 2.2 percent and wages by 1.8 percent. It would keep the distribution of the tax burden roughly the same as it is today. Taxes would be cut for taxpayers in the bottom 90 percent while slightly raised for taxpayers in the top 10 percent. This plan would also be revenue-neutral in the long run, on a static basis.

This plan would reduce the corporate income tax rate from the current 35 percent to 28.5 percent. In addition, 50 percent bonus depreciationBonus depreciation allows firms to deduct a larger portion of certain “short-lived” investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings in the first year. Allowing businesses to write off more investments partially alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. would be permanently extended. All non-structural business tax expenditures would be eliminated.[7] Lastly, net interest expense by businesses would be limited to 30 percent of pre-tax earnings.

On the individual side, the current seven tax brackets would be consolidated into four at 12.5, 25, 33, and 38 percent. The standard deduction would be increase from $6,350 ($12,700 married filing jointly; $9,350 head of household) to $7,000 ($14,000 married filing jointly; $10,500 head of household). The child tax credit would be increased from the current $1,000 to $1,500. The EITC for childless filers would also be doubled. Both the Alternative Minimum Tax and the Pease limitation on itemized deductions would be eliminated.

To broaden the individual income tax base, the state and local tax deductionA tax deduction allows taxpayers to subtract certain deductible expenses and other items to reduce how much of their income is taxed, which reduces how much tax they owe. For individuals, some deductions are available to all taxpayers, while others are reserved only for taxpayers who itemize. For businesses, most business expenses are fully and immediately deductible in the year they occur, but others, particularly for capital investment and research and development (R&D), must be deducted over time. would be eliminated.

| Provision | Long-Run Annual Revenue Impact (Billions of 2017 Dollars) | Long-Run Annual Revenue Impact %GDP | Long-run Impact on GDP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eliminate the alternative minimum tax | -$35.54 | -0.2% | -0.3% |

| Consolidate individual income tax brackets into four rates, of 12.5 percent, 25 percent, 33 percent, and 38 percent | -$72.37 | -0.4% | 0.6% |

| Eliminate the state and local tax deduction | $171.70 | 0.9% | -0.2% |

| Increase the standard deduction to $7,000 ($14,000 married filing jointly; $10,500 head of household) | -$12.27 | -0.1% | 0.0% |

| Expand the child tax credit and the earned income tax credit | -$69.69 | -0.4% | 0.2% |

| Lower the corporate income tax rate to 28.5 percent | -$54.06 | -0.3% | 1.5% |

| Permanently extend bonus depreciation | -$15.61 | -0.1% | 0.6% |

| Limit the deductibility of interest to 30% of earnings | $47.82 | 0.2% | -0.1% |

| Eliminate business tax expenditures | $47.78 | 0.2% | 0.1% |

| Total | $7.76 | 0.0% | 2.4% |

Option D

Option D would substantially lower business tax rates, in addition to other improvements to the income tax system, and would lead to lower federal revenue in the long run.

Option D is nearly identical to Option C, but would reduce tax rates for businesses more. These additional tax cuts would make the plan lose revenue in the long run and require accompanying spending reductions (in order to comply with the Byrd Rule). We estimate that in the long run revenue would be approximately $70 billion lower on an annual basis (in 2017 dollars).

This plan would reduce the corporate income tax rate from the current 35 percent to 25 percent. In addition, 50 percent bonus depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. would be permanently extended. All non-structural corporate tax expenditures would be eliminated.[8] Lastly, net interest expense deductions by businesses would be limited to 30 percent of pre-tax earnings.

On the individual side, the current seven tax brackets would be consolidated into four at rates of 12.5, 25, 33, and 38 percent. The standard deduction would be increased from $6,350 ($12,700 married filing jointly; $9,350 head of household) to $7,000 ($14,000 married filing jointly; $10,500 head of household). The child tax credit would be increased from the current $1,000 to $1,500. The EITC for childless filers would also be doubled. Both the Alternative Minimum Tax and the Pease limitation on itemized deductions would be eliminated.

The plan would also implement a 30 percent maximum tax rate for pass-through businesses.

| Provision | Long-Run Annual Revenue Impact (Billions of 2017 Dollars) | Long-Run Annual Revenue Impact %GDP | Long-run Impact on GDP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eliminate the alternative minimum tax | -$35.54 | -0.2% | -0.3% |

| Consolidate individual income tax brackets into four rates, of 12.5 percent, 25 percent, 33 percent, and 38 percent | -$72.37 | -0.4% | 0.6% |

| Eliminate the state and local tax deduction | $171.70 | 0.9% | -0.2% |

| Increase the standard deduction to $7,000 ($14,000 married filing jointly; $10,500 head of household) | -$12.27 | -0.1% | 0.0% |

| Expand the child tax credit and the earned income tax credit | -$69.69 | -0.4% | 0.2% |

| Lower the corporate income tax rate to 25 percent | -$90.25 | -0.3% | 1.5% |

| Permanently extend bonus depreciation | -$15.61 | -0.1% | 0.6% |

| Limit the deductibility of interest to 30% of earnings | $47.82 | 0.2% | -0.1% |

| Eliminate business tax expenditures | $47.78 | 0.2% | 0.1% |

| Cap the tax rate on pass-through business income at 30 percent | -$42.37 | -0.2% | 0.6% |

| Total | -$70.79 | -0.4% | 3.7% |

Other Issues

Permanent vs. Temporary Policy

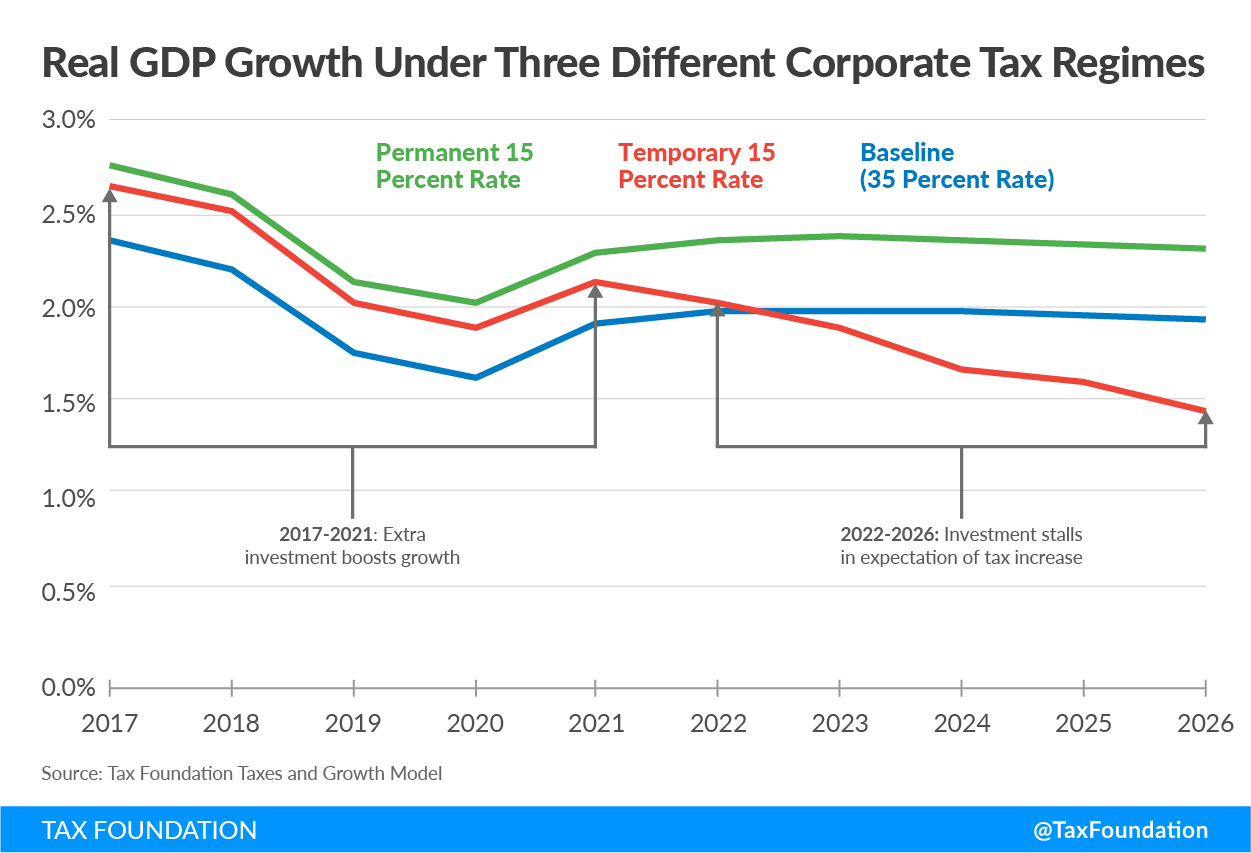

All four of these plans were modeled assuming that all policies were permanent. However, it is possible that lawmakers opt to make all or some of a tax plan temporary in order to navigate budget rules.

Lawmakers should be cautious of using temporary policy. It creates uncertainty for taxpayers. Taxpayers, especially businesses, may by unsure whether certain policies will remain in place in the long run. This may reduce their willingness to invest in new projects.

Making a tax policy temporary would also negate the positive growth impacts of the policy. In our modelling, we found that a temporary corporate income tax rate cut to 15 percent would at first increase economic growth, but as the policy approached expiration, it would reduce corporate investment to below baseline.[9] This means companies would invest even less than if the corporate rate had remained at 35 percent.

Phase-ins and Transitional Impacts

Many tax policies have transitional impacts on the budget, meaning that they can increase or decrease revenue more in the first ten years than they do in the long run. This is important to understand when putting together a tax plan, in the context of budget rules that limit how large a tax cut can be in the budget window and outside of the budget window. These rules will require lawmakers to pay close attention to how much tax plans impact the revenues in the short run.

We modeled all of these tax plans looking at their impact on revenue in the steady state: how they would impact revenues on an annual basis, after all policies have fully phased in. Many of these plans, though, could potentially impact revenue over the budget window in different ways depending on how they are structured.

A good example of a tax plan that is revenue-neutral in the long run, but loses revenue in the short run is Option A. This is because Option A converts the corporate income tax into a cash-flow tax. This conversion could potentially reduce revenue significantly in the first ten years. For instance, lawmakers could allow companies to continue to write-off old investments under the old tax regime at the same time as expensing new investments. In addition, lawmakers could allow companies to continue to deduct interest from old loans, but eliminate the deduction for expense on new loans. The combination would reduce revenue in the short run, even though this combination raises revenue in the long run.

This approach to enacting a cash-flow tax would reduce revenue in the first ten years. We estimate that the corporate changes in Option A would reduce revenue by $1.87 trillion over the budget window on a static basis if the corporate rate were immediately reduced to 22.5 percent and paired with full expensing of capital investments and the elimination of the net interest expense deduction.

| Provision | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2017-2026 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth Model, March 2017 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Immediately Enact 22.5% Corporate Tax Rate | -$127.05 | -$133.62 | -$139.91 | -$151.36 | -$150.02 | -$152.44 | -$155.90 | -$161.21 | -$167.71 | -$175.15 | -$1,514.37 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allow full expensing for corporations and allow corporations to write off old assets under current law schedules | -$185.89 | -$150.23 | -$127.64 | -$117.81 | -$97.88 | -$87.30 | -$83.11 | -$81.13 | -$80.78 | -$80.78 | -$1,092.56 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eliminate the deduction for net interest expense and allow corporations to deduct interest from loans acquired prior to enactment of tax reform | $0.61 | $3.96 | $8.83 | $15.20 | $21.36 | $27.96 | $34.37 | $41.50 | $49.28 | $57.99 | $261.07 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eliminate corporate tax expenditures | $38.68 | $39.69 | $40.52 | $42.43 | $45.02 | $47.07 | $49.47 | $52.15 | $55.21 | $57.43 | $467.67 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total 10-Year Cost of Corporate Tax Reform | -$273.65 | -$240.19 | -$218.19 | -$211.53 | -$181.52 | -$164.71 | -$155.18 | -$148.70 | -$144.00 | -$140.51 | -$1,878.19 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

However, if the corporate rate were gradually reduced from 35 percent to 22.5 percent over six years and full expensing were phased-in over time through what is called “neutral cost recovery,”[10] the ten-year cost of these changes would drop significantly, to $400 billion over ten years. These changes, paired with others, could even out the budgetary impact of a tax reform proposal and prevent it from losing much revenue in the first few years.

| Provision | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2017-2026 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth Model, March 2017 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase-in 22.5 Corporate Rate | -$30.78 | -$51.85 | -$74.60 | -$102.38 | -$123.28 | -$147.04 | -$155.90 | -$161.21 | -$167.71 | -$175.15 | -$1,189.90 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Neutral Cost Recovery | $0.00 | -$2.84 | -$6.32 | -$9.92 | -$12.94 | -$15.01 | -$16.69 | -$18.82 | -$20.94 | -$23.45 | -$126.92 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eliminate the deduction for net interest expense and allow companies to deduct interest from loans acquired prior to enactment of tax reform | $9.05 | $17.67 | $25.58 | $33.97 | $38.06 | $41.90 | $48.27 | $56.41 | $65.39 | $75.14 | $411.44 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eliminate corporate tax expenditures | $48.26 | $48.09 | $47.51 | $48.15 | $49.42 | $49.78 | $49.47 | $52.15 | $55.21 | $57.43 | $505.47 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total 10-Year Cost of Corporate Tax Reform | $26.53 | $11.07 | -$7.83 | -$30.17 | -$48.75 | -$70.36 | -$74.84 | -$71.48 | -$68.05 | -$66.03 | -$399.91 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lawmakers could choose a number of ways to phase in provisions, to either reduce the upfront cost of tax plans, or ease the burden on taxpayers. Lawmakers could gradually reduce the top marginal tax rate, phase in increases to credits and the standard deduction, phase in caps on itemized deductions, and allow companies to pay taxes on existing foreign-source profits over a number of years. All of these options would have an impact on revenue over the budget window, but would not impact the ultimate level of federal revenue.

Dynamic Revenue

For this analysis we did not include dynamic revenue estimates, as we limited our analysis to tax reform plans that would deficit-neutral on a conventional basis. However, we estimated that all of these plans would improve the tax code and boost the long-run size of the economy. The larger economy would broaden the tax base and provide the federal government with additional revenue, which could be used to reduce rates further or reduce the budget deficit.

Dynamic analysis is a useful tool to understand the economic impacts of different tax policies and how tax changes ultimately impact federal revenues. Those additional revenues could be useful in funding tax reform, but lawmakers should be cautious. As these four plans show, not all tax plans produce the same amount of economic growth and would not provide the same amount of revenue feedback. A tax reform like Option A, which includes full expensing of capital investments, would produce much more dynamic revenue than a reform that doesn’t. As such, lawmakers shouldn’t assume that all tax reform proposals will produce a significant amount of dynamic revenue feedback.

Modeling Note

All analyses are done with the March 2017 version of the Tax Foundation’s Taxes and Growth (TAG) Macroeconomic model. The TAG model is a small open economy neoclassical growth model. Individual income tax changes are estimated using the IRS Public Use File, which is a database of over 150,000 sample tax returns that represent the population of taxpayers. Corporate and business tax changes are projected using Federal Reserve, Bureau of Economic Analysis, and Congressional Budget Office Data. The revenue impact of certain business tax expenditures is estimated with the help of Joint Committee on Taxation and Treasury Department estimates. In our analysis, we assume that all tax changes are enacted on a permanent basis. In our conventional or “static” estimates, we assume that that the corporate income tax falls 75 percent on capital and 25 percent on labor.

| Option A | Option B | Option C | Option D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Individual Income Tax Rates and Taxable Income Brackets (Single) |

12% > $0 20.5% > $37,950 37% > $191,650 | 10% > $0 25% > $37,950 38% > $191,650 | 12.5%: > $0 25%: > $37,950 33%: > $191,650 38%: > $416,700 | 12.5%: > $0 25%: > $37,950 33%: > $191,650 38%: > $416,700 |

|

Standard Deduction |

$12,000; $18,000; $24,000 | $50,000; $100,000; $75,000 | $7,000; $14,000; $10,500 | $7,000; $14,000; $10,500 |

|

Personal Exemption |

Replaced with a $500 non-refundable credit for non-child dependents | Eliminated | No change | No change |

|

Itemized Deductions |

All eliminated except for the home mortgage interest deduction and the charitable contribution deduction. The home mortgage interest deduction is capped at $500,000 acquisition debt | All eliminated except for the state and local tax deduction, the home mortgage interest deduction, and the charitable contributions deduction. | State and local tax deduction eliminated | State and local tax deduction eliminated |

|

Child Tax Credit |

Increased to $1,500. First $1,000 is refundable. Phase-out for CTC for married couples begins at two times the AGI threshold as singles and heads of household | Eliminated | Increased to $2,000. Phase-out of CTC increased to $150,000 AGI ($300,000 for married couples filing jointly). | Increased to $2,000. Phase-out of CTC increased to $150,000 AGI ($300,000 for married couples filing jointly). |

|

Earned Income Tax Credit |

No Change | Eliminated | Phase-in and Phase-out doubled for childless filers | Phase-in and Phase-out doubled for childless filers |

|

Other Personal Credits |

All eliminated except for the foreign tax credit | All personal credits eliminated except for the foreign tax credit and replaced with three new refundable tax credits: A child credit of $2,400 (per child), an additional child credit of up to $2,200 (per child, up to three children), and a work credit of up to $2,000 (per person). | No change | No change |

|

Capital Income (Capital Gains, Dividends, Interest) |

All capital income taxed as ordinary income, but is provided a 40 percent deduction against taxable income | All capital income taxed as ordinary income. | No change | No change |

|

Business Income (Pass-through businesses) |

No change | No change | No change | Maximum rate of 30 percent; Rules to prevent gaming assumed. |

|

Alternative Minimum Tax |

Eliminated | Eliminated | Eliminated | Eliminated |

|

Other Individual Income Tax Changes |

Pease limitation eliminated | Pease limitation and Net Investment Income Tax eliminated | Pease limitation eliminated | Pease limitation eliminated |

|

Corporate Income Tax Rate |

22.5 percent | 15 percent | 28.5 percent | 25 percent |

|

Cost Recovery |

Full expensing of capital investments | 50 percent bonus depreciation made permanent | 50 percent bonus depreciation made permanent | 50 percent bonus depreciation made permanent |

|

Interest Expense |

Business interest expenses are only deductible against interest income. No deduction for net interest expense | No change | Net business interest expense deduction limited to 30 percent of earnings | Net business interest expense deduction limited to 30 percent of earnings |

|

Business Tax Expenditures |

Several eliminated (list, below) | Several eliminated (list, below) | Several eliminated (list, below) | Several eliminated (list, below) |

|

Estate Tax |

Eliminated | No change | No change | No change |

|

Other Tax Changes/Notes |

95 percent dividends received deduction (territorial) | Enact a 13 percent broad-based, border adjusted value-added tax. | None | None |

| Work opportunity tax credit |

| Tax credit for orphan drug research |

| Tax credits for clean-fuel burning vehicles and refueling property |

| Tax incentives for preservation of historic structures |

| Indian employment credit |

| Industrial CO2 capture and sequestration tax credit |

| Investment credit for rehabilitation of structures (other than historic) |

| New markets tax credit |

| Energy investment credit |

| Energy production credit |

| Advanced energy property credit |

| Alcohol fuel credits |

| Bio-diesel and small agri-biodiesel producer tax credits |

| Credit for construction of new energy efficient homes |

| Credit for employee health insurance expenses of small business |

| Credit for holders of zone academy bonds |

| Credit for holding clean renewable energy bonds |

| Credit for increasing research activities |

| Credit for investment in clean coal facilities |

| Credit to holders of Gulf Tax Credit Bonds. Section 199 deduction for manufacturing activities |

[1] Non-structural tax expenditures refer to tax expenditures that neither move our current tax system closer to a consumption-based tax nor change the treatment of foreign profits of multinational corporations, such as deferral.

[2] Eric Toder, “Using a VAT to Reform the Income Tax,” Tax Policy Center, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/412489-Using-a-VAT-to-Reform-the-Income-Tax.PDF

[3] Michael Schuyler, “An Analysis of Senator Cardin’s Progressive Consumption Tax,” Tax Foundation. https://taxfoundation.org/analysis-senator-cardin-s-progressive-consumption-tax/

[4] Scott Greenberg and Kyle Pomerleau, “Details and Analysis of Rep. Jim Renacci’s Tax Reform Proposal,” Tax Foundation. https://taxfoundation.org/details-and-analysis-rep-jim-renacci-s-tax-reform-proposal/

[5] Progressive Consumption Tax. https://www.cardin.senate.gov/pct

[6] We estimate that this tax would have a broad base of roughly 90 percent of domestic consumption. Exemptions for certain goods and services would require a higher rate to raise the same amount of revenue.

[7] Non-structural tax expenditures refer to tax expenditures that neither move our current tax system closer to a consumption-based tax nor change the treatment of foreign profits of multinational corporations, such as deferral.

[8] Non-structural tax expenditures refer to tax expenditures that neither move our current tax system closer to a consumption-based tax nor change the treatment of foreign profits of multinational corporations, such as deferral.

[9] Alan Cole, “Why Temporary Corporate Tax Cuts Won’t Generate Much Growth,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 549, June 12, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/temporary-tax-cuts-corporate/

[10] Neutral cost recovery would provide adjustments for inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. and an interest rate for current law depreciation deductions. Under this cost recovery regime, companies would still have to deduct investments over time as under current law, but would be able to recover the full present value of the investment as they do under expensing. For more information see: Kyle Pomerleau, “How to Reduce the Up Front Cost of Full Expensing,” Tax Foundation. https://taxfoundation.org/reduce-front-cost-full-expensing/

Share this article