Last week, we wrote a piece showing that full expensing has significant up-front costs that eventually dissipate. This makes full expensingFull expensing allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of certain investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings. It alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. look much more expensive in the first ten years than it will ultimately cost on an ongoing basis. This is because investments made in previous years under prior depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. schedules would continue to be written off at the same time as new investment is fully expensed. In fact, we estimated that the annual cost of full expensing in the long run is less than the annual cost of a 25 percent corporate income tax rate.

Even though expensing may cost a lot less in the out years, the up-front transitional costs are still significant. As such, lawmakers may want to find ways to limit those transitional costs’ impacts on the deficit.

One way to reduce the cost of full expensing during the transition is to enact something called “neutral cost recovery” (NCR). Under NCR, companies would get the benefit of full expensing: deductions for capital investments would get the full present value write-offs and bring the marginal tax rate on those assets down to zero, but the government would not suffer large transitional costs.

This is how it would work: instead of providing a full write-off for capital costs, the federal government would keep the current law’s depreciation schedule. However, depreciation allowances would be adjusted to an interest rate to offset both the effect of inflation and the time value of money.

The downside of depreciation is that deductions for capital costs are spread out over time. A dollar today is worth more than a dollar five years from now due to both inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. and the time value of money.

The table below shows how deductions for a $500 investment are taken over time. The first row roughly approximates depreciation under current law. Although the company ends up deducting $500 in nominal costs over five years, the deductions in later years lose value. Thus, the company only gets to recover $463, or 92.6 percent of its initial costs in present value.

Expensing fixes this issue by allowing for a full deduction for the entire investment in the first year. The second row shows deductions under expensing. The company gets to deduct the full cost of the investment in the first year. Since deductions are not spread out over time, they do not lose value in real terms.

| Year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Law Depreciation Deductions | $100.00 | $100.00 | $100.00 | $100.00 | $100.00 | $500.00 |

| Present Value | $100.00 | $96.15 | $92.46 | $88.90 | $85.48 | $462.99 |

| Expensing | $500.00 | $0.00 | $0.00 | $0.00 | $0.00 | $500.00 |

| Present Value | $500.00 | $0.00 | $0.00 | $0.00 | $0.00 | $500.00 |

| Neutral Cost Recovery | $100.00 | $104.00 | $108.16 | $112.49 | $116.99 | $541.63 |

| Present Value | $100.00 | $100.00 | $100.00 | $100.00 | $100.00 | $500.00 |

The third row shows what NCR would look like. Under NCR, a company still needs to depreciate assets over time according to a schedule. However, annual deductions are adjusted by an interest rate to offset the declining value of deductions over time. In the first year, the deduction is the same as it is under current law. But as time goes on, the deductions grow in nominal terms. The second year, the company deducts $104 and the next year $108. These larger annual deductions end up offsetting the impact of the declining value of money over time. What you can see is that the present value of the deduction remains constant.

For companies, this means that they get the full value of their deduction as if they expensed it all at once. This would come with the same economic benefits: a marginal tax rateThe marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. of zero on new investment and the higher output, wages, and employment that is associated.

For the federal government, this has the effect of phasing in the cost of full expensing slowly over time.

As mentioned above, expensing reduces revenue significantly in the short run. This is because companies in the first few years after enactment are taking both full deductions for new investments and continuing to take deductions for investments they made in previous years. In the first few years, this greatly reduces corporate taxable income and corporate taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. revenues. However, the cost comes down significantly as old investments are retired.

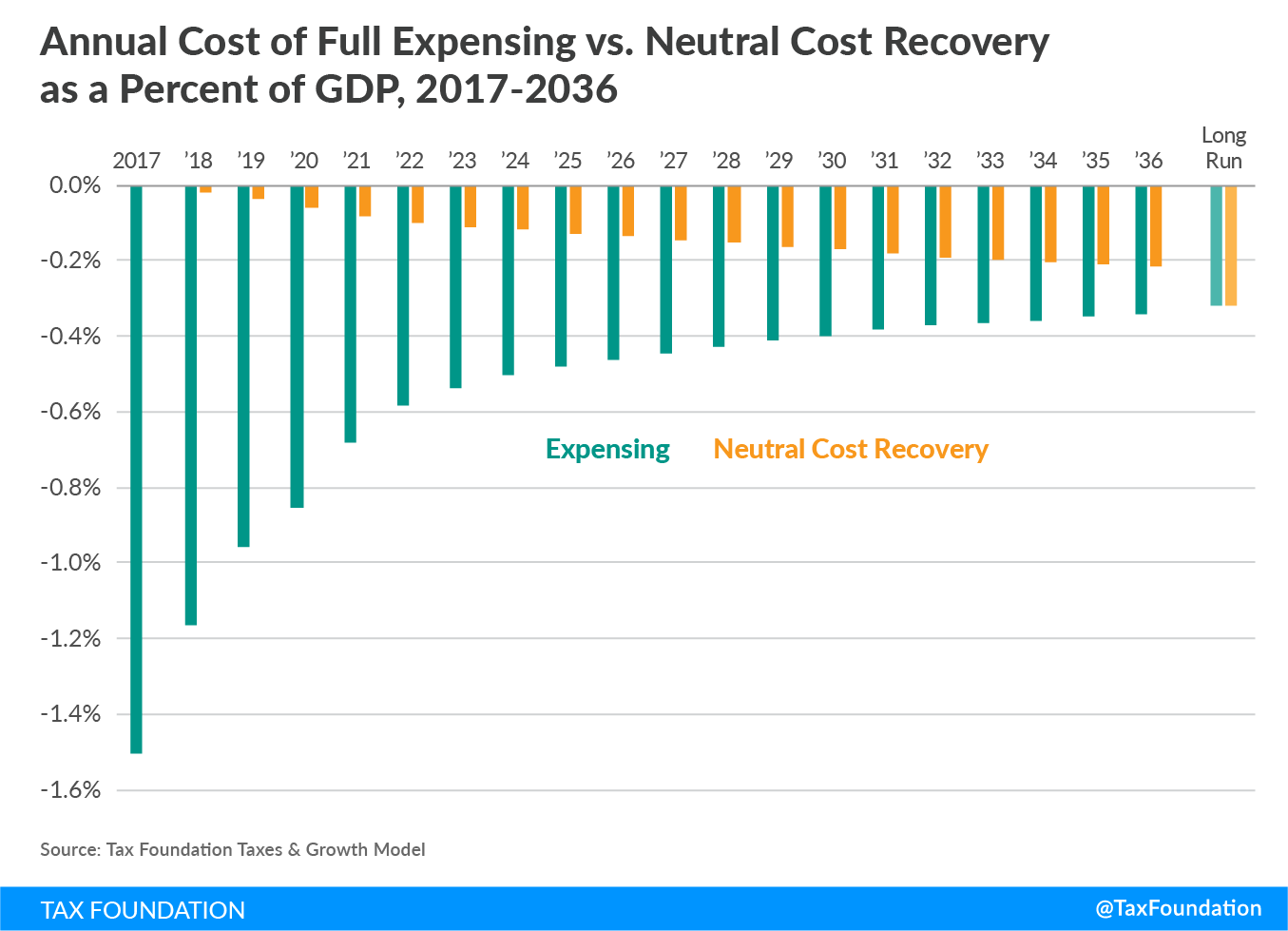

In the chart below, you see that expensing reduces federal revenue the most in the first five years. In later years, the cost comes down significantly to about 0.3 percent of GDP on annual basis.

Under NCR, you don’t get the same bulge in deductions. Instead, corporate taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. shrinks slowly over time as companies take progressively larger deductions for new investments.

Unsurprisingly the steady-state revenue impact of NCR ends up being identical to that of expensing. This makes sense: if your interest rate adjustment to depreciation deductions offsets the time value of money, the total stream of deductions for a given investment will exactly equal a complete upfront deduction in present value.

The obvious advantage of NCR is that it doesn’t come with the same up-front costs as full expensing. This makes it easier to construct a revenue-neutral tax reform plan within the budget window. But since the annual cost ends up matching that of expensing, it still requires offsets in later years. This is an important consideration if tax reform is done through reconciliation. The tax plan would need to comply with the Byrd Rule and not increase deficits outside the budget window.

There are a couple of downsides with NCR compared to expensing. The federal government will still have a system of depreciation, which requires defining which assets qualify for which depreciation schedule, which keeps the tax code more complex than necessary. However, there is no reason NCR couldn’t be paired with a significant simplification of the depreciation system. And lawmakers could pair NCR with expensing by providing expensing for short-lived assets and smaller businesses and NCR for long-lived assets and large companies.

Another potential downside is that some companies may have internal discount rates in excess of what the government adjusts the depreciation schedules. The discount rate companies use for investments can vary based on the firm’s cost of borrowing and the risk of a given investment. An adjustment of 4 percent may be good for one investment, but insufficient for another. Companies may also have inconsistent discount rates over time. Neither of these issues are a concern with full expensing because all companies, regardless of their discount rate, get a full deduction in the first year.

Full expensing of capital investments is probably the single most significant tax change lawmakers could make to encourage economic growth. However, it can come with large up-front costs. Although those costs are only temporary, they can also be addressed with “neutral cost recoveryCost recovery is the ability of businesses to recover (deduct) the costs of their investments. It plays an important role in defining a business’ tax base and can impact investment decisions. When businesses cannot fully deduct capital expenditures, they spend less on capital, which reduces worker’s productivity and wages. ” (NCR). NCR basically phases in the cost of expensing slowly while providing an immediate benefit to new investment.

Share this article