Key Findings

- The Senate’s version of the TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. Cuts and Jobs Act would reform both individual income and corporate income taxes and would move the United States to a territorial system of business taxation.

- According to the Tax Foundation’s Taxes and Growth Model, the plan would significantly lower marginal tax rates and the cost of capital, which would lead to a 3.7 percent increase in GDP over the long term, 2.9 percent higher wages, and an additional 925,000 full-time equivalent jobs.

- The Senate’s version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act is a pro-growth tax plan, which, when fully implemented, would spur an additional $1.26 trillion in federal revenues from economic growth. These new revenues would reduce the cost of the plan substantially. Depending on the baseline used to score the plan, current policy or current law, the new revenues could bring the plan closer to revenue neutral.

- On a static basis, the plan would lead to 1.2 percent higher after-tax incomeAfter-tax income is the net amount of income available to invest, save, or consume after federal, state, and withholding taxes have been applied—your disposable income. Companies and, to a lesser extent, individuals, make economic decisions in light of how they can best maximize their earnings. on average for all taxpayers and 4.5 percent higher after-tax income on average for the top 1 percent in 2027. When accounting for the increased GDP, after-tax incomes of all taxpayers would increase by 4.4 percent in the long run.

- While our results differ from those of the Joint Committee on Taxation, some of these results are attributable to long-standing differences between the two models.

Introduction

On November 9, 2017, Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-UT), Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, released the Senate’s version of a tax reform plan, known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. This follows the release by House Ways and Means Chairman Kevin Brady (R-TX) of the House version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act on November 2, 2017.[1] The Senate version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would reform the individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. code by lowering tax rates on wages, investment, and business income; broadening the tax base; and simplifying the tax code. The plan would lower the corporate income tax rate to 20 percent and move the United States from a worldwide to a territorial system of taxation.

Our analysis[2] finds that the Senate plan would reduce marginal tax rates on labor and investment. As a result, we estimate that the plan would increase long-run GDP by 3.7 percent. The larger economy would translate into 2.9 percent higher wages and result in an additional 925,000 full-time equivalent jobs. Due to the larger economy and the broader tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. , the plan would generate $1.26 trillion in additional revenue over the next decade on a dynamic basis.

Changes to the Individual Income Tax

- Retains the current seven-bracket structure, but lowers rates for several brackets. Bracket widths are modified as well (Table 1 and Table 2).

| Note: Tax brackets are for single tax filers. Brackets differ for married and head of household filers. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Current Law | Proposal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rates | Brackets | Rates | Brackets | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10% | $0-$9,525 | 10% | $0-$9,525 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15% | $9,525-$38,700 | 12% | $9,525-$38,700 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25% | $38,700-$93,700 | 22.5% | $38,700-$60,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28% | $93,700-$195,450 | 25% | $60,000-$170,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 33% | $195,451-$424,950 | 32.5% | $170,000-$200,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 35% | $424,951-$426,700 | 35% | $200,000-$500,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 39.6% | $426,701+ | 38.5% | $500,000+ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Note: The Head of Household filing status is retained, with a separate bracket schedule. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Current Law | Proposal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rates | Brackets | Rates | Brackets | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10% | $0-$19,050 | 10% | $0-$19,050 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15% | $19,051-$77,400 | 12% | $19,050-$77,400 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25% | $77,400-$156,150 | 22.5% | $77,400-$120,00 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28% | $156,150-$237,950 | 25% | $120,000-$390,800 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 33% | $237,950-$424,950 | 32.5% | $390,800-$450,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 35% | $424,950-$480,050 | 35% | $450,000-$1,000,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 39.6% | $480,051+ | 38.5% | $1,000,000+ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Indexes tax bracketsA tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. and other provisions by the Chained CPI measure of inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. .

- Increases the standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. Taxpayers who take the standard deduction cannot also itemize their deductions; it serves as an alternative. to $12,000 for single filers, $18,000 for heads of household, and $24,000 for joint filers in 2018 (compared to $6,500, $9,550, and $13,000 respectively under current law).

- Eliminates the personal exemption.

- Retains the charitable contribution deduction and the mortgage interest deductionThe mortgage interest deduction is an itemized deduction for interest paid on home mortgages. It reduces households’ taxable incomes and, consequently, their total taxes paid. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) reduced the amount of principal and limited the types of loans that qualify for the deduction. for purchases, but eliminates the mortgage interest deduction for home equity debt. Fully repeals the state and local tax deductionA tax deduction allows taxpayers to subtract certain deductible expenses and other items to reduce how much of their income is taxed, which reduces how much tax they owe. For individuals, some deductions are available to all taxpayers, while others are reserved only for taxpayers who itemize. For businesses, most business expenses are fully and immediately deductible in the year they occur, but others, particularly for capital investment and research and development (R&D), must be deducted over time. , except for taxes paid or accrued in carrying on a trade or business.

- Eliminates a number of other deductions, such as those subject to the 2 percent floor.

- Expands the child tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. from $1,000 to $1,650, while increasing the phaseout from $110,000 to $1 million for married couples. The first $1,000 would be refundable, with the amount increasing with inflation until it hits the $1,650 base amount.

- Eliminates the alternative minimum tax.

Changes to Business Taxes

- Lowers the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate to 20 percent, starting in 2019.

- Establishes a 17.4 percent deduction of qualified business income from certain pass-through businesses. Specific service industries, such as health, law, and professional services, are excluded. However, joint filers with income below $150,000 and other filers with income below $75,000 can claim the deduction fully on income from service industries.

- Allows full and immediate expensing of short-lived capital investments. Increases the section 179 expensing cap from $500,000 to $1 million. Reduces asset lives for residential and nonresidential real property from 39 years to 25 years.

- Limits the deductibility of net interest expense to 30 percent.

- Eliminates net operating loss carrybacks and limits carryforwards to 90 percent of taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. Taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. .

- Eliminates the domestic production activities deduction (section 199) and modifies other provisions, such as the orphan drug credit and the rehabilitation credit.

- Enacts deemed repatriationRepatriation is the process by which multinational companies bring overseas earnings back to the home country. Prior to the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the US tax code created major disincentives for US companies to repatriate their earnings. Changes from the TCJA eliminate these disincentives. of currently deferred foreign profits, at a rate of 10 percent for cash and cash-equivalent profits and 5 percent for reinvested foreign earnings.

- Moves to a territorial system with base erosion rules.

- Eliminates the corporate alternative minimum tax.

Other Changes

- Doubles the estate tax exemptionA tax exemption excludes certain income, revenue, or even taxpayers from tax altogether. For example, nonprofits that fulfill certain requirements are granted tax-exempt status by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), preventing them from having to pay income tax. from $5.6 million to $11.2 million.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeImpact on the Economy

According to the Tax Foundation’s Taxes and Growth Model, the Senate’s version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would increase the long-run size of the U.S. economy by 3.7 percent (Table 3). The larger economy would result in 2.9 percent higher wages and a 9.9 percent larger capital stock. The plan would also result in 925,000 additional full-time equivalent jobs.

The larger economy and higher wages are due chiefly to the significantly lower cost of capital under the proposal, which reduces the corporate income tax rate and accelerates expensing of capital investment.

| Source: Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth Model, November 2017. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Change in long-run GDP | 3.7% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Change in long-run capital stock | 9.9% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Change in long-run wage rate | 2.9% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Change in long-run full-time equivalent jobs (thousands) | 925 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

These long-run economic changes are generated by several key provisions of the bill, particularly the corporate and individual income tax rate cuts, and the accelerated expensing provisions. Table 4 below includes the five most important changes to increase long-run economic growth.

| Source: Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth Model, November 2017. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Note: These numbers add to more than 3.7 percent, the total growth from the plan, because several other provisions have negative growth effects. A full list of economic effects by provisions is found in Table 5. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Long-run GDP Growth from Selected Provisions, 2018-2027 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provision | Long-run GDP Growth | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Lower the corporate income tax rate to 20 percent, effective January 1, 2019.

|

2.7% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Adjust individual income tax rates and thresholds, creating seven rates of 10%, 12%, 22.5%, 25%, 32.5%, 35%, and 38.5%. |

1.0% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Create a 17.4% deduction for pass-through business income. Generally, income from service businesses is ineligible, but households with less than $75,000/$150,000 in taxable income can claim a full deduction for service business income. In the case of partnership and S corporation income, income subject to the deduction is limited to 50 percent of the taxpayer’s W-2 wages.

|

0.6% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Increase the standard deduction to $12,000/$18,000/$24,000.

|

0.4% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Reduce the depreciable lives of residential and nonresidential buildings to 25 years. Allow businesses to deduct 100 percent of 168(k) property for 5 years. Increase the §179 expensing amount from $500,000 to $1 million, and increase the phaseout threshold from $2 million to $2.5 million. Limit interest deductions to 30 percent of EBIT for businesses with over $15 million in gross receipts.

|

0.2% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

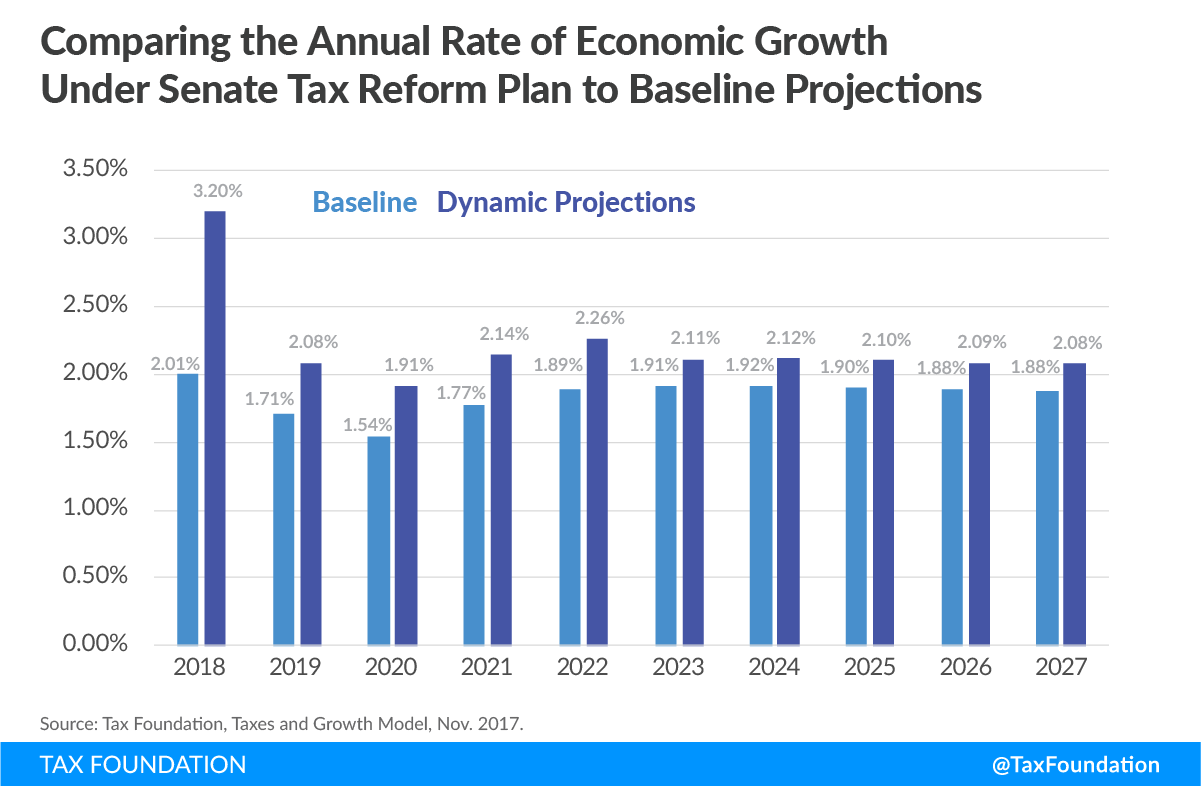

The growth of GDP under this plan, however, is not linear. The full and immediate expensing of equipment plus the shorter asset lives for structures encourage capital investment. This incentive is increased by the one-year delay on a corporate rate cut. The first-year corporate tax rate of 35 percent (the same under current law) means that businesses would have a larger tax savings from expensing than under a 20 percent rate. Firms would move to make investments quickly to take advantage of the savings, resulting in front-loaded economic activity. The projected economic growth in 2018 (year 1) is 1.19 percent above the baseline. These economic outcomes rely on the assumption that the corporate income tax rate cut is permanent, as currently outlined in the Senate’s plan.

The initial spike in growth is reduced later during the decade, but the plan still significantly increases economic growth over the long run. The figure below illustrates this phenomenon.

Due to the interaction of a delayed corporate rate cut and the immediate implementation of temporary full expensing, the Senate version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act accelerates capital investment, generating a faster dynamic response than the House version of the plan. The current version of the House plan takes longer for these economic results to be achieved.

Due to the interaction of a delayed corporate rate cut and the immediate implementation of temporary full expensing, the Senate version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act accelerates capital investment, generating a faster dynamic response than the House version of the plan. The current version of the House plan takes longer for these economic results to be achieved.

Impact on Revenue

If fully implemented, the proposal would reduce federal revenue by $1.78 trillion over the next decade on a static basis (Table 3) using a current law baseline. The plan would reduce individual income tax revenue, excluding the changes for noncorporate business tax filers, by $462 billion over the next decade. Tax revenue from the corporate income tax and from the taxation of pass-through businessA pass-through business is a sole proprietorship, partnership, or S corporation that is not subject to the corporate income tax; instead, this business reports its income on the individual income tax returns of the owners and is taxed at individual income tax rates. income would fall by $1.22 trillion. The remainder of the revenue loss would be due to the doubling of the estate tax exemption, resulting in a revenue loss of $95 billion.

On a dynamic basis, this plan would generate an additional $1.26 trillion in revenues, reducing the cost of the plan to $516 billion over the next decade. The larger economy would boost wages and thus broaden both the income and payroll tax base. As a result, the federal government would see a smaller revenue loss from personal tax changes, of $309 billion. The reduction in tax revenue from business changes would also be smaller on a dynamic basis, at $69 billion. The corporate tax revenue loss would be most significant in the short term because of the temporary expensing provision for short-lived assets, which would encourage more investment and result in businesses taking larger deductions for capital investments in the first five years of the plan.

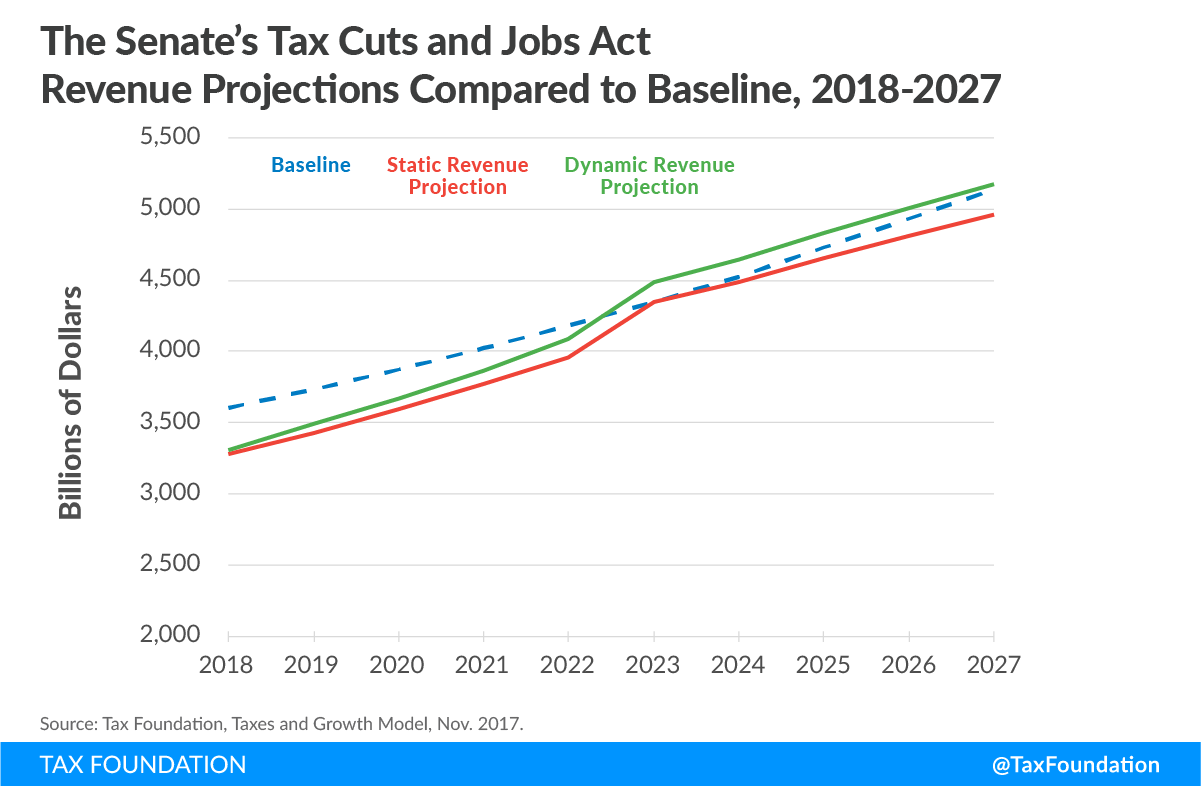

The figure below compares static and dynamic revenue collection to the current law baseline. By the end of the decade, dynamic revenues have exceeded the baseline. In fact, dynamic revenues exceed the current law baseline in 2023, when the temporary expensing provisions expire, as the costs of the plan fall.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

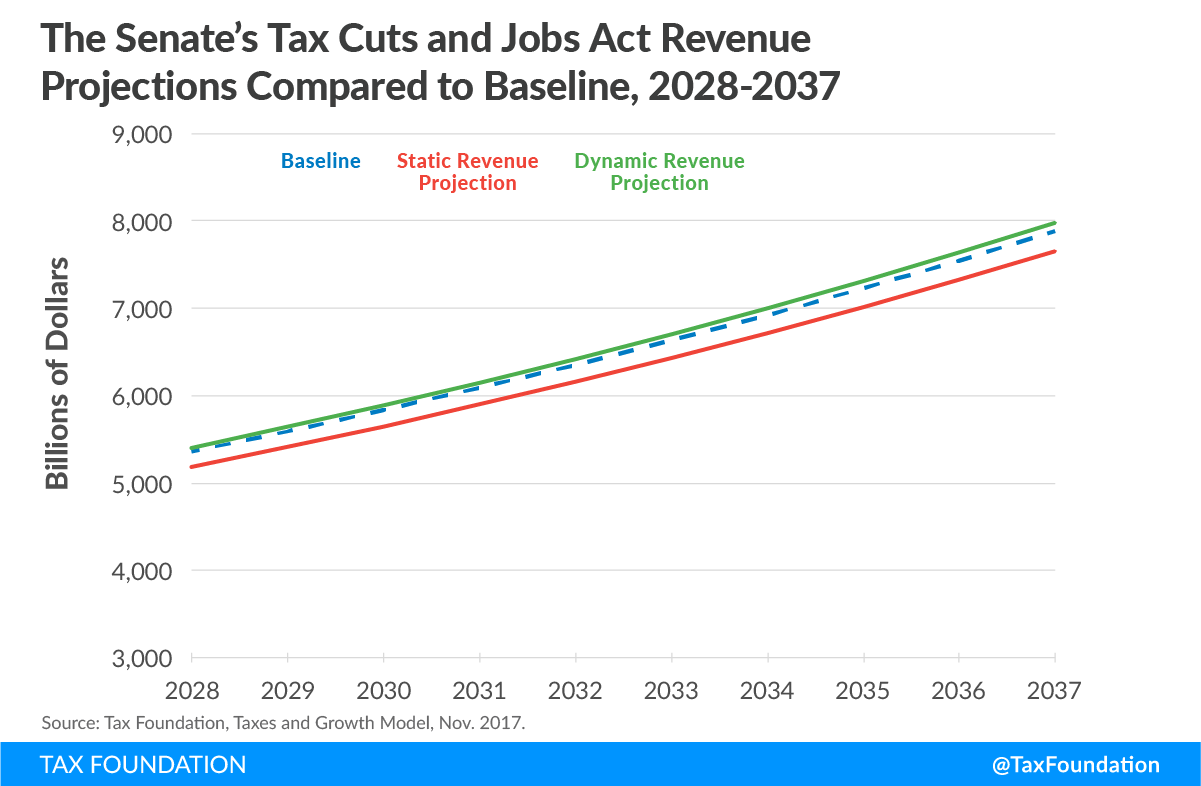

SubscribeIn the second decade, this plan has dynamic revenue estimates above the current law revenue baseline in all years. However, the static costs of this plan are still negative in the second decade.

These results, however, should not be interpreted to mean that these tax changes are self-financing. Instead, they illustrate that the Senate version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act includes a number of revenue offsets to reduce the overall cost of the tax rate cuts included in the plan.

The first large set of base broadeners is the elimination of a number of credits and deductions for individuals. Notably, the entire state and local tax deduction would be eliminated (except as relates to business activity), and the mortgage interest deduction would be limited to only acquisition debt. Home equity debt would no longer be deductible. The plan would also repeal a number of deductions previously limited by a 2 percent floor. These provisions would raise $1.55 trillion over the next decade.

The plan would also expand the standard deduction to $12,000 for single filers, $18,000 for heads of household, and $24,000 for married couples. It would expand the child tax credit from $1,000 to $1,650, with the refundable portion ($1,000) increasing using a Chained CPI inflation adjustment. The plan also repeals personal exemptions. In total, these provisions raise $113 billion on net over the next decade.

On the business side, the bill includes several base broadeners. It would limit the net interest deduction to 30 percent of earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT), including for already originated loans. It would also limit or eliminate a number of business tax expenditures, such as the domestic production activities (section 199) deduction, the orphan drug credit, and the deduction for entertainment expenses. Repealing and limiting many of these expenditures would generate $415 billion in revenue.

The largest source of revenue loss in the first decade would be the individual and corporate rate cuts and faster depreciation of capital investments. The Senate’s version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would retain the current seven brackets, but would modify both their widths and tax rates. The top marginal tax rateThe marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. would fall from 39.6 percent under current law to 38.5 percent, with many other rates decreasing as well. These changes would reduce revenues by $1.91 trillion. The corporate income tax rate would fall from 35 percent to 20 percent on January 1, 2019, reducing revenues by $1.40 trillion. The plan would also provide many pass-through businesses with a 17.4 percent deduction for pass-through business income. Service business would be ineligible, except for households with taxable income below $75,000 for single filers and $150,000 for married filers. This provision reduces revenue by $527 billion.

Table 5 summarizes the revenue impacts, both static and dynamic, of each of the major provisions.

| Source: Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth Model, November 2017. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Note: Changes to the taxation of pass-through businesses is a change to the individual income tax revenue collections, but for simplicity, we’ve included those changes under the Business subcomponent. However, the differential rate on pass-through businesses does have interactions with the individual income tax rate and bracket restructuring under this plan. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Change in static revenue, 2018-2027 (billions of dollars) | Change in long-run GDP | Change in dynamic revenue, 2018-2027 (billions of dollars) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Individual |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Eliminate the alternative minimum tax. |

-$389 | -0.3% | -$484 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Adjust individual income tax rates and thresholds, creating seven rates of 10%, 12%, 22.5%, 25%, 32.5%, 35%, and 38.5%. |

-$1,912 | 1.0% | -$1,578 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Increase the standard deduction to $12,000/$18,000/$24,000. |

-$1,023 | 0.4% | -$912 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Repeal personal exemptions. |

$1,795 | -0.6% | $1,612 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Increase the child tax credit amount to $1,650. Initially, only the first $1,100 of the credit is refundable. Decrease the phase-in threshold of the refundable portion of the credit to $2,500. Increase the phaseout threshold of the credit to $500,000 for married filers and $250,000 for other filers. Allow the credit to be claimed for children under age 18. Create a $500 nonrefundable credit for non-child dependents. |

-$659 | 0.2% | -$598 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Repeal the deduction for state and local taxes paid, the deduction for interest on home equity indebtedness, the deduction for tax preparation expenses, and several miscellaneous deductions. Limit the casualty loss deduction, and modify limits on the charitable deduction. Repeal the Pease limitation on itemized deductions. |

$1,506 | -0.5% | $1,349 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Modify or repeal other personal deductions, credits, and exclusions. |

$42 | 0.0% | $41 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Index bracket thresholds, the standard deduction amount, the refundable portion of the child tax credit, and other provisions to chained CPI (economic effect not modeled). |

$178 | 0.0% | $178 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Individual subtotal |

-$462 | 0.2% | -$390 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Business |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Lower the corporate income tax rate to 20 percent, effective 1/1/2019. |

-$1,396 | 2.7% | -$626 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Create a 17.4% deduction for pass-through business income. Generally, income from service businesses is ineligible, but households with less than $75,000/$150,000 in taxable income can claim a full deduction for service business income. In the case of partnership and S corporation income, income subject to the deduction is limited to 50 percent of the taxpayer’s W-2 wages. |

-$527 | 0.6% | -$355 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Reduce the depreciable lives of residential and nonresidential buildings to 25 years. Allow businesses to deduct 100 percent of 168(k) property for 5 years. Increase the §179 expensing amount from $500,000 to $1 million, and increase the phaseout threshold from $2 million to $2.5 million. Limit interest deductions to 30 percent of EBIT for businesses with over $15 million in gross receipts. |

$185 | 0.2% | $462 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Eliminate business tax expenditures, etc. |

$415 | -0.2% | $345 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Move to a territorial tax system, accompanied by several rules to prevent base erosion. |

-$74 | 0.0% | -$74 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Enact a deemed repatriation of deferred foreign-source income, at rates of 5% and 10%. |

$179 | 0.0% | $179 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Business subtotal |

-$1,218 | 3.3% | -$69 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Double the estate and gift tax exemption. |

-$95 | 0.1% | -$57 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

TOTAL |

-$1,775 | 3.7% | -$516 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

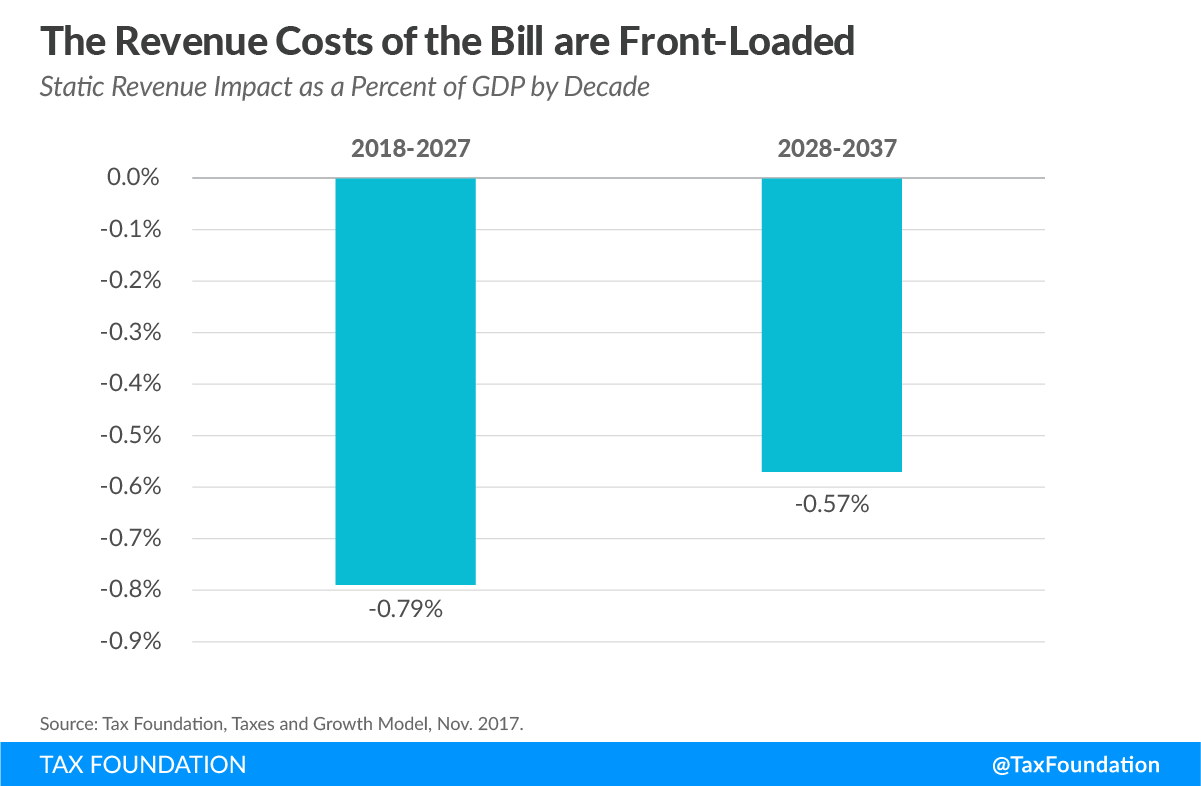

Revenue Impacts Beyond the First Decade

Although the plan would reduce federal revenues by $1.78 over the next 10 years, the plan would also have a smaller impact on revenues in the second decade. There are several provisions that contribute to the first decade’s higher transitional costs, including changes to expensing rules and inflation measures.

The plan would index tax brackets, the standard deduction, and other provisions to chained CPI rather than CPI. This provision would raise relatively little revenue in the short term, but would increase revenue over time as these two inflation indices diverge.

Moving to temporary full expensingFull expensing allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of certain investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings. It alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. for short-lived assets would also reduce revenues in the first decade. Because this provision is currently slated to expire after five years, its impacts in the second decade are limited. However, any future changes to this provision, such as extending it or making it permanent, could impact revenues in the future.

The plan includes a major transitional revenue raiser, deemed repatriation. This proposal would tax corporations on their current deferred offshore profits and raise $179 billion over the next decade. We assume that this provision would only raise revenue in the first decade.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeTaken together, these results mean that the Senate plan would cost less in future decades. We estimate that this bill would reduce federal revenues on a static basis by 0.79 percent of GDP in the first decade compared to 0.57 percent of GDP in the second decade.

Components of the Reduced Deficit Impact

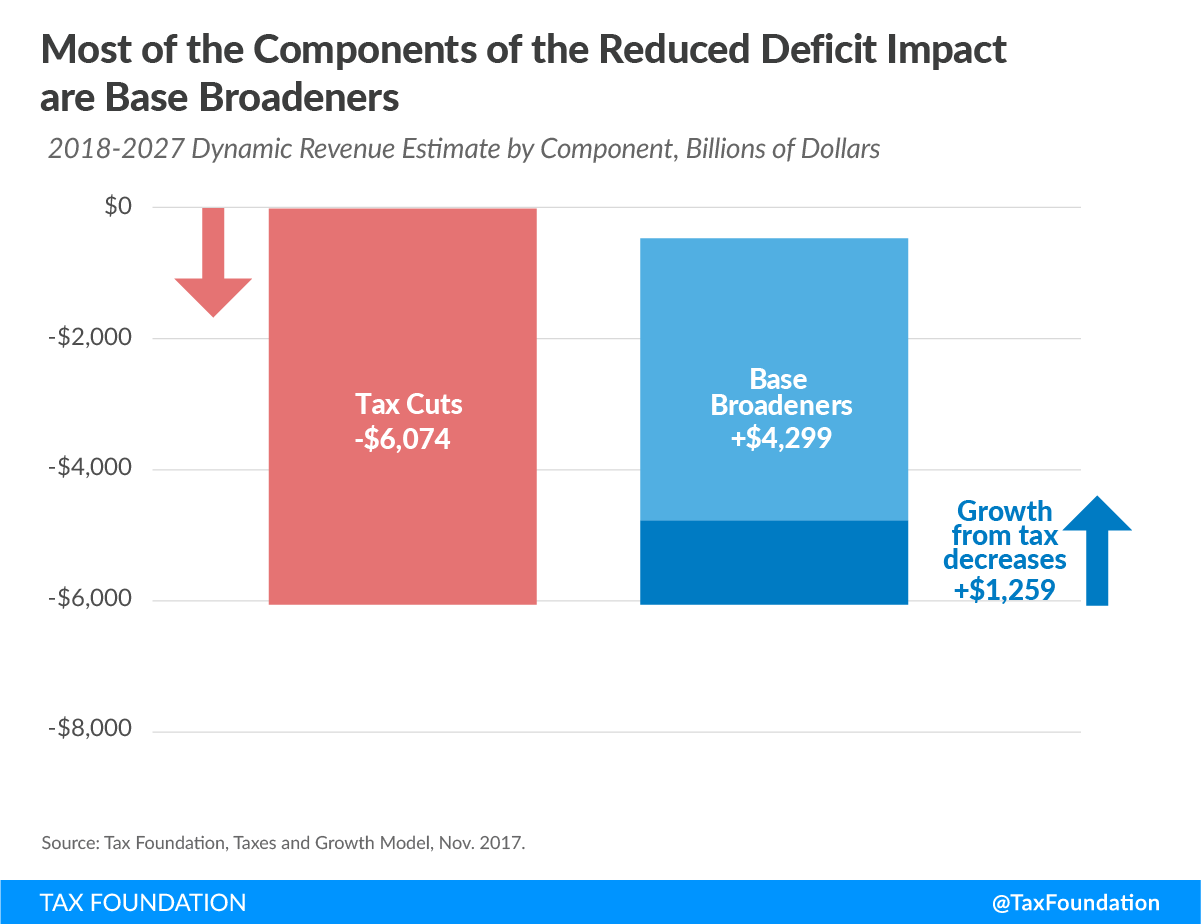

The dynamic revenue impact of -$516 billion over the next decade can be broken down into three components: tax reductions, economic growth, and revenue raisers.

The tax reductions in this plan include, but are not limited to, the cut in the corporate income tax rate to 20 percent, temporary expensing, and the reduction in marginal tax rates for most individuals. Combined, these tax cuts would reduce federal revenues by $6.07 trillion over the next decade, if enacted alone.

The second piece is the expected increase in revenue due to economic growth. The bill would reduce marginal tax rates on work and investment. Our model finds that these marginal tax rates would significantly increase the long-run size of the economy. The larger economy would boost wages, thereby increasing the tax base, especially for the individual income and payroll taxes. The resulting growth would reduce the 10-year cost of the plan by $1.26 trillion on net.

Finally, the revenue raisers in the plan, such as the elimination of several itemized deductions for individuals and the repeal of many businesses tax expenditures, would significantly expand the tax base, reducing the revenue loss of the tax plan by $4.30 trillion over the next decade.

Distributional Impact of the Plan

On a static basis, the Senate’s version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would increase the after-tax incomes of taxpayers in every taxpayer group in 2018. The bottom 80 percent of taxpayers (those in the bottom four quintiles) would see an average increase in after-tax income ranging from 1.1 to 1.9 percent. Taxpayers in the top 1 percent would see the largest increase in after-tax income on a static basis, of 7.5 percent, driven by the lower pass-through tax rate and the lower corporate income tax.

By 2027, the distribution of the federal tax burden would look different, for several reasons. First, the bill includes temporary provisions, such as increased expensing for short-lived capital investments. Because these provisions would expire by 2027, taxpayers would not benefit from them in that year. Second, by 2027 taxpayers would be subject to the effect of indexing bracket thresholds to chained CPI, which would reduce the benefit of the increased standard deduction and individual income tax cuts.

Accounting for these factors, most groups of taxpayers would still see an increase in after-tax income, on average, in 2027. The bottom 80 percent of taxpayers would see an average increase in after-tax income ranging from 0.3 to 0.4 percent. The top 1 percent would see the largest increase in after-tax income on a static basis, of 4.5 percent.

Additionally, by 2027, the economic effects of a tax bill will have largely phased in. Taking these effects into account, taxpayers as a whole would see an increase in after-tax incomes of at least 3.7 percent, with the lowest increase for those between 90 and 95 percent of income. The top 1 percent of all taxpayers would see an increase in after-tax income of 4.0 percent on a dynamic basis.

These dynamic results include the impact of both individual and corporate income tax changes on the U.S. economy. Static estimates assume that 25 percent of the cost of the corporate income tax is borne by labor. Dynamic estimates assume that 70 percent of the full burden of the corporate income tax is borne by labor, due to the negative effects of the tax on investment and wages.

| Source: Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth Model, November 2017. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| All changes, 2018 | All changes, 2027 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income Group | Static | Income Group | Static | Dynamic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0% to 20% | 1.2% | 0% to 20% | 0.4% | 4.4% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20% to 40% | 1.9% | 20% to 40% | 0.3% | 4.6% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40% to 60% | 1.7% | 40% to 60% | 0.4% | 5.0% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 60% to 80% | 1.1% | 60% to 80% | 0.4% | 4.7% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 80% to 100% | 3.1% | 80% to 100% | 1.8% | 4.1% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 80% to 90% | 2.4% | 80% to 90% | 0.5% | 4.2% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 90% to 95% | 1.0% | 90% to 95% | 0.6% | 3.7% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 95% to 99% | 2.1% | 95% to 99% | 0.9% | 4.2% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 99% to 100% | 7.5% | 99% to 100% | 4.5% | 4.0% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TOTAL | 2.5% | TOTAL | 1.2% | 4.4% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Differences with the Model Results from the Joint Committee on Taxation

On November 9, 2017, the Joint Committee on Taxation released a static estimate of the revenue effects of the Senate’s version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.[3] While preparing this report, the Tax Foundation relied in several instances on the Joint Committee’s estimates, particularly regarding tax provisions about which little public data exists. However, for most major provisions of the bill, the Tax Foundation estimated revenue effects using its own revenue model. On some provisions, the Tax Foundation model results were quite similar to those of the Joint Committee; for other provisions, the results diverged.

Overall, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimated that the plan would reduce federal revenue by $1.50 trillion between 2018 and 2027. This is a lower cost estimate than the Tax Foundation’s static score of $1.78 trillion. The Joint Committee on Taxation did not release a dynamic score of the plan.

The bulk of the discrepancy between the static scores of the Joint Committee on Taxation and those of the Tax Foundation can be traced to three provisions: lowering individual rates, limiting the interest deduction, and enacting temporary expensing for short-lived assets. The Tax Foundation’s higher estimate for the cost of consolidating and lowering individual tax rates may be due to the fact that the Tax Foundation’s model utilizes taxpayer microdata from 2008, while the Joint Committee’s model may have access to more recent taxpayer data. In addition, it is well known that the Joint Committee’s model finds smaller static revenue effects from changes to business interest deductibility, depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. , and cost recoveryCost recovery refers to how the tax system permits businesses to recover the cost of investments through depreciation or amortization. Depreciation and amortization deductions affect taxable income, effective tax rates, and investment decisions. than outside models. This may be due to differing assumptions about businesses with net operating losses.[4] We may assume that more companies would be able to take advantage of these provisions than the Joint Committee’s model.

Uncertainty in Modeling Estimates

There are three primary sources of uncertainty in modeling the provisions of the Senate’s version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act: the significance of deficit effects, the timing of economic effects, and expectations regarding the extension of temporary provisions.

Some economic models assume that there is a limited amount of saving available to the United States to fund new investment opportunities when taxes on investment are reduced, and that when the federal budget deficit increases, the amount of available saving for private investment is “crowded-out” by government borrowing, which reduces the long-run size of the U.S. economy. While past empirical work has found evidence of crowd-out, the estimated impact is usually small. Furthermore, global savings remain high, which may help explain why interest rates remain low despite rising budget deficits. We assume that a deficit increase will not meaningfully crowd out private investment in the United States.[5]

We are also forced to make certain assumptions about how quickly the economy would respond to lower tax burdens on investment. There is an inherent level of uncertainty here that could impact the timing of revenue generation within the budget window.

Finally, we assume that temporary tax changes will expire on schedule, and that business decisions will be made in anticipation of this expiration. To the extent that investments are made in the anticipation that temporary expensing provisions might be extended, economic effects could exceed our projections.

Conclusion

The Senate’s version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act represents a dramatic overhaul of the U.S. tax code. Our model results indicate that the plan would be pro-growth, boosting long-run GDP 3.7 percent and increasing the domestic capital stock by 9.9 percent. Wages, long stagnant, would increase by 2.9 percent, while the reform would produce 925,000 new jobs. These economic effects would have a substantial impact on revenues as well, as indicated by the plan’s significantly lower revenue losses under dynamic scoring.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeAppendix

The distributional tables included in the paper reflect all tax changes in the Senate’s version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. As noted above, much of the increase in after-tax incomes for higher-income earnings is attributable to changes in business taxation, such as the lower corporate income tax rate and the lower pass-through business income tax rate. For reference, we have included distributional tables of the personal income tax changes only, including changes to individual income tax rates, deductions, and credits.

| Source: Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth Model, November 2017. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal changes only, 2018 | Personal changes only, 2027 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income Group | Static | Income Group | Static | Dynamic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0% to 20% | 0.5% | 0% to 20% | 0.3% | 0.4% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20% to 40% | 1.1% | 20% to 40% | 0.7% | 0.8% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 40% to 60% | 1.0% | 40% to 60% | 0.9% | 1.0% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 60% to 80% | 0.8% | 60% to 80% | 0.6% | 0.7% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 80% to 100% | 0.2% | 80% to 100% | 0.0% | 0.1% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 80% to 90% | 0.4% | 80% to 90% | 0.1% | 0.2% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 90% to 95% | -0.2% | 90% to 95% | -0.5% | -0.4% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 95% to 99% | 0.2% | 95% to 99% | 0.0% | 0.1% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 99% to 100% | 0.3% | 99% to 100% | 0.1% | 0.2% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TOTAL | 0.5% | TOTAL | 0.3% | 0.4% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[1] This bill is still working its way through the House of Representatives. On November 9, 2017, the House Committee on Ways and Means approved the bill by a 24-16 margin. It is expected to be considered by the full House of Representatives in the next week.

[2] Our Senate analysis includes corrections made to our model in November 2017, to address concerns raised by the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. As a consequence, these results are not directly comparable to the results issued on November 3, 2017, titled “Details and Analysis of the 2017 House Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.”

[3] The Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Revenue Effects Of The Chairman’s Mark of the ‘Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,’ Scheduled For Markup By The Committee On Finance on November 13, 2017,” JCX-52-17, November, 9, 2017, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5033.

[4] Alan Cole, “Economic and Budgetary Effects of Permanent Bonus Expensing,” Tax Foundation, September 16, 2015, https://taxfoundation.org/economic-and-budgetary-effects-permanent-bonus-expensing.

[5] Gavin Ekins, “Time to Shoulder Aside ‘Crowding Out’ As an Excuse Not to Do Tax Reform,” Tax Foundation, November, 7, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/crowding-out-tax-reform/.

Share this article