Key Findings

- The majority of companies in the United States are pass-through businesses. These businesses are not subject to the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. ; instead, their income is reported on their owners’ taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. returns and subject to the individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. .

- Over the past thirty years, the pass-through businessA pass-through business is a sole proprietorship, partnership, or S corporation that is not subject to the corporate income tax; instead, this business reports its income on the individual income tax returns of the owners and is taxed at individual income tax rates. sector has expanded significantly. Pass-through businesses now earn more net income than traditional C corporations and employ the majority of the private-sector workforce.

- On the federal level, pass-through businesses are subject to a top marginal tax rateThe marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. of 44.6 percent. This means that, in most U.S. states, pass-through businesses can face marginal tax rates that exceed 47 percent.

- Some policymakers have expressed interest in taxing some large pass-through businesses as C corporations. However, there are strong theoretical and economic arguments for the current tax treatment of pass-through businesses, which are not subject to the problematic double tax regime faced by C corporations.

- On the flip side, some lawmakers have proposed creating a new, lower tax rate for pass-through business income. Aside from concerns that this approach would create opportunities for tax avoidance, it is also difficult to justify why income from pass-through businesses should be subject to lower tax rates than income from wages and salaries.

Introduction

Much of the tax reform debate in the United States centers on the federal corporate income tax. However, many people are not aware that the vast majority of businesses in the U.S. are not subject to the corporate income tax at all.

Over 90 percent of businesses in the United States are pass-through businesses, whose income is reported on the business owners’ tax returns and is taxed under the individual income tax. These businesses earn the majority of all business income in the U.S. and employ over half of the private-sector workforce in 49 out of 50 states.

Although they are not subject to the corporate income tax, many pass-through businesses still face a considerable tax burden on their investments and profits. Pass-through businesses are subject to both the federal individual income tax, with a top rate of 43.4 percent, and state and local income taxes, with rates ranging up to 13.3 percent.

As the tax reform debate heats up in 2017, the question of whether to change the tax treatment of pass-through businesses will pay a central role. As this paper will argue, there is a strong case to be made for keeping the current system of taxing pass-through businesses: a single layer of tax, levied at the same rates that apply to wages and salaries.

What Are Pass-Through Businesses?

Under the U.S. tax code, several types of businesses are not subject to the corporate income tax. Instead of paying taxes on the business level, these companies “pass” their income “through” to their owners. The business owners are then required to report the business income on their personal tax returns, so that the business income is taxed under the individual income tax.

There are three major categories of pass-through businesses: sole proprietorships, partnerships, and S corporations.[1] All three categories of pass-through business are taxed in a similar manner; they are distinguished from one another by their legal form of organization, as well as the number of owners.

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Sole Proprietorship | An unincorporated business owned by a single individual. Individuals report sole proprietorship income on Schedule C of the 1040 tax form. |

| Partnership | An unincorporated business with multiple owners, either individuals or other businesses. |

| S Corporation | A domestic corporation that can only be owned by U.S. citizens (not other corporations or partnerships) and can only have up to 100 shareholders. |

It is useful to contrast pass-through businesses with “C corporations,” or companies that are subject to the corporate income tax. Unlike pass-through businesses, C corporations can face up to two layers of tax on their income. First, income earned by a C corporation is taxed under the corporate income tax in the year it is earned. Then, when a C corporation distributes its income to shareholders in the form of dividends, or when the shareholders sell their stock and realize a capital gain, the income can be taxed a second time, under the individual income tax. By contrast, income earned by pass-through businesses is generally subject to one layer of tax, on the owners’ tax returns, without a second layer of tax on the business level.[2]

Another important difference between pass-through businesses and C corporations has to do with tax timing. In general, the owners of pass-through businesses are required to pay taxes on a business’s income in the same year the income is earned. This is also the case for the first layer of tax on C corporations, the corporate income tax, which is paid in the same year that a corporation earns income. However, shareholders of C corporations are able to defer the second layer of tax – the individual income tax on dividends or capital gains – until a corporation distributes its profits or until a shareholder realizes a gain.

Pass-Through Businesses are a Major Part of the U.S. Economy

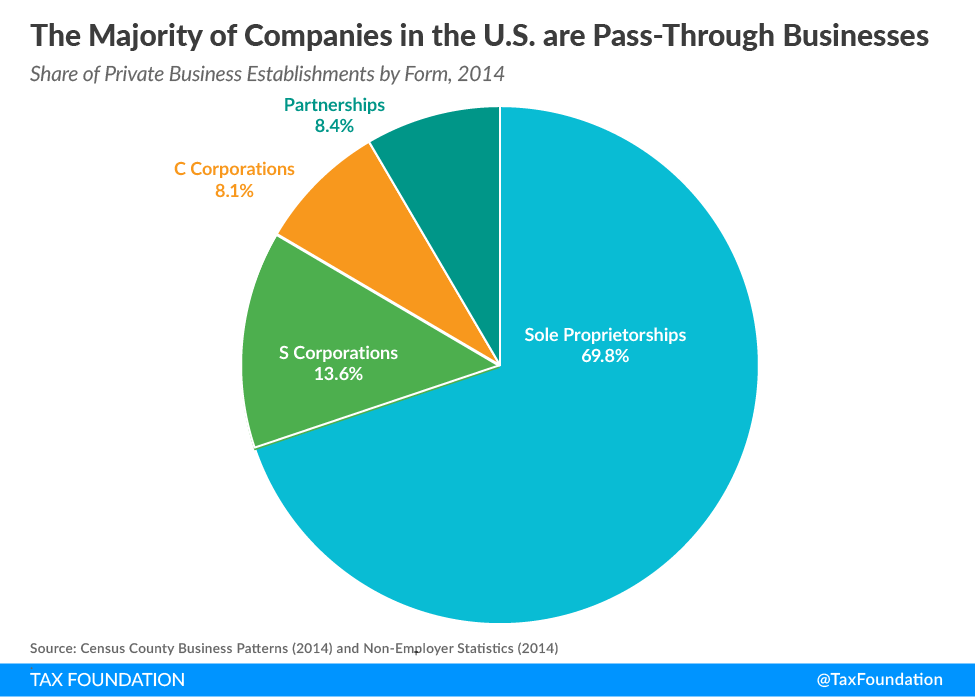

The vast majority of businesses in the United States are pass-through businesses.[3] In 2014, out of the 30.8 million private business establishments in the United States, 28.3 million were pass-through businesses (Figure 1).[4]

The most common form of pass-through businesses in the United States is the sole proprietorship. There were 21.5 million sole proprietorships in 2014, accounting for 69.8 percent of all private businesses. On the other hand, C corporations are relatively uncommon. Only 2.5 million businesses filed taxes as C corporations in 2014, or 8.1 percent of all private businesses.

Figure 1

In addition, pass-through businesses are also responsible for more than half of private-sector jobs in the U.S. (Figure 2). In 2014, 57.3 percent of the U.S. private-sector workforce was employed or self-employed at a pass-through business.[5] In numerical terms, U.S. pass-through businesses employed 73.0 million people in 2014, compared to 54.3 million employees of C corporations.[6]

Within the pass-through sector, in 2014, S corporations had the most employees: 32.5 million people, or 25.5 percent of the private sector workforce. Although sole proprietorships are the most common form of business in the U.S., they accounted for only 19.6 percent of all private-sector jobs. This is because most sole proprietorships consist of one self-employed individual, without any other employees.

Figure 2

In 49 out of 50 states, pass-through businesses employ over 50 percent of the private workforce. The one exception is Hawaii, where pass-through businesses account for 49.9 percent of private-sector jobs. In four states, pass-through businesses are responsible for over 65 percent of the private-sector workforce: Montana (68.6 percent), South Dakota (66.3 percent), Idaho (65.4 percent), and Vermont (65.2 percent).

The Growth of the Pass-Through Sector

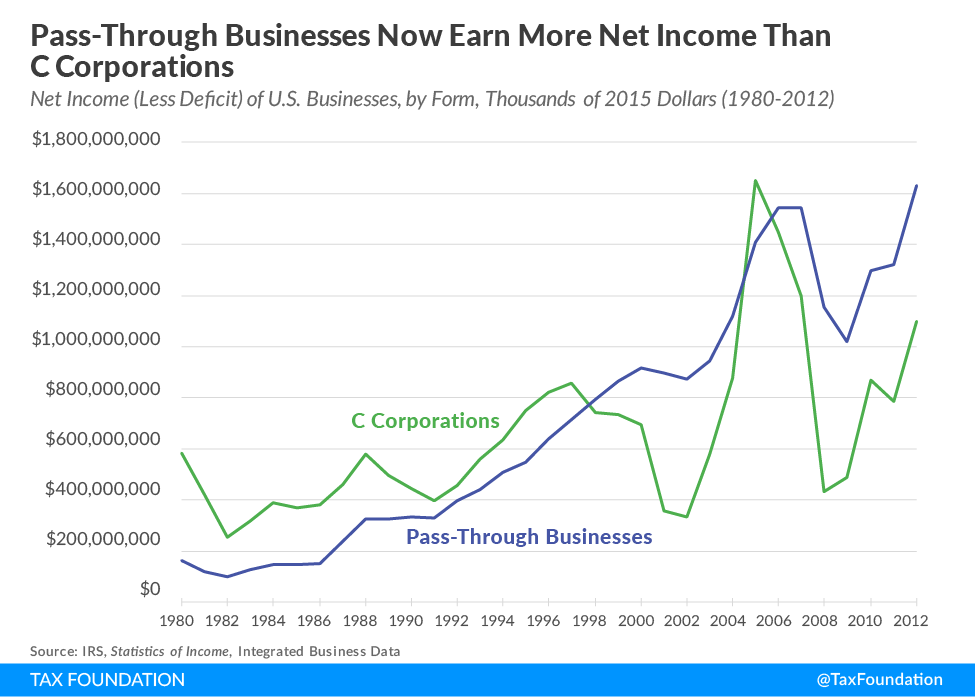

The dominance of pass-through businesses in the U.S. economy is a relatively recent phenomenon. In 1980, C corporations accounted for the overwhelming majority of U.S. business income, earning over three times as much as partnerships, S corporations, and sole proprietorships combined (Figure 3).[7]

However, the share of business income earned by pass-through businesses began to grow rapidly in the late 1980s. One important cause of this shift was the Tax Reform Act of 1986 (TRA86), which lowered the top individual income tax rate from 50 percent to 28 percent, making it more profitable than beforehand to operate as a pass-through business.[8]

By 1998, pass-through businesses had begun to earn a greater share of business income than C corporations. Since then, pass-through businesses have continued to earn more income than C corporations in every year except 2005. In 2012, pass-through businesses earned $1.63 trillion in net income, compared to $1.10 trillion of net income earned by C corporations.[9]

Figure 3

The rapid growth of the pass-through sector in recent decades is also apparent from the number of tax returns filed by different business forms (Figure 4).[10] In 1980, there were more tax returns filed by C corporations (2.2 million) than by partnerships (1.4 million) and S corporations (0.5 million) combined. By 2012, there were over four times as many returns filed by partnerships (3.4 million) and S corporations (4.2 million) as the returns filed by C corporations (1.6 million).

Overall, between 1980 and 2012, the number of pass-through businesses filing tax returns rose substantially, from 10.9 million businesses to 31.1 million. Concurrently, the share of all business tax returns filed by C corporations fell dramatically, from 16.6 percent in 1980 to 4.9 percent in 2012.

Figure 4

The fastest growth in the pass-through sector came among S corporations. The number of tax returns filed by S corporations rose by 671 percent between 1980 and 2012.

Pass-Through Businesses Can Face Substantial Marginal Tax Rates

While pass-through businesses are not subject to the corporate income tax, they face several substantial taxes on the federal, state, and local levels.

The most significant tax on U.S. pass-through businesses is the federal individual income tax, which is levied at rates ranging up to 39.6 percent. Pass-through businesses pass their income and losses directly to their owners, who include them in their gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total of all income received from any source before taxes or deductions. It includes wages, salaries, tips, interest, dividends, capital gains, rental income, alimony, pensions, and other forms of income. For businesses, gross income (or gross profit) is the sum of total receipts or sales minus the cost of goods sold (COGS)—the direct costs of producing goods, including inventory and certain labor costs. on Form 1040. As a result, the marginal income tax rate on a pass-through business is determined by whatever tax bracket the business’s owners fall into.

| Bracket | Single Filers | Married Joint Filers | Head of Household Filers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | $0 to $9,325 | $0 to $18,650 | $0 to $13,350 |

| 15% | $9,325 to $37,950 | $18,650 to $75,900 | $13,350 to $50,800 |

| 25% | $37,950 to $91,900 | $75,900 to $153,100 | $50,800 to $131,200 |

| 28% | $91,900 to $191,650 | $153,100 to $233,350 | $131,200 to $212,500 |

| 33% | $191,650 to $416,700 | $233,350 to $416,700 | $212,500 to $416,700 |

| 35% | $416,700 to $418,400 | $416,700 to $470,700 | $416,700 to $444,500 |

| 39.6% | $418,400+ | $470,700+ | $444,500+ |

|

Source: Kyle Pomerleau, “2017 Tax Brackets,” Tax Foundation, 2017 Tax Brackets. Note: Income thresholds refer to dollars of taxable income. |

|||

There are two other federal taxes that apply to pass-through businesses: the self-employment tax and the Net Investment Income Tax. Both of these taxes are dedicated toward funding Social Security and Medicare.

The federal self-employment tax applies to sole proprietorship income, as well as partnership income earned by general partners (together, these are referred to as “self-employment income”).[11] It is designed to mimic the federal payroll taxA payroll tax is a tax paid on the wages and salaries of employees to finance social insurance programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance. Payroll taxes are social insurance taxes that comprise 24.8 percent of combined federal, state, and local government revenue, the second largest source of that combined tax revenue. system (FICA), which applies at a rate of 15.3 percent for compensation under $127,200 and a rate of 2.9 percent on compensation above that threshold.[12] As such, individuals who make less than $127,000 in wages and self-employment income combined are subject to a 15.3 percent self-employment tax rate, while self-employment income above that threshold is taxed at 2.9 percent.

Since the 2013 tax year, the self-employment tax has also included a 0.9 percent surtaxA surtax is an additional tax levied on top of an already existing business or individual tax and can have a flat or progressive rate structure. Surtaxes are typically enacted to fund a specific program or initiative, whereas revenue from broader-based taxes, like the individual income tax, typically cover a multitude of programs and services. on self-employment income over $200,000 ($250,000 for joint filers), which is designed to mimic the Additional Medicare Tax.[13] Unlike the ordinary self-employment tax, this surtax applies based on household self-employment income, rather than individual self-employment income. All in all, the top self-employment tax rate is 3.8 percent.

The Net Investment Income Tax applies to partnership income earned by limited partners, as well as S corporationAn S corporation is a business entity which elects to pass business income and losses through to its shareholders. The shareholders are then responsible for paying individual income taxes on this income. Unlike subchapter C corporations, an S corporation (S corp) is not subject to the corporate income tax (CIT). income earned by “passive shareholders,” as well as several other sources of income.[14] It is levied at a rate of 3.8 percent, on household net investment income over $200,000 ($250,000 for joint filers).

| Self-Employment Income | Self-Employment Tax Rate | Net Investment Income | Net Investment Income Tax Rate |

| $0 to $127,200 | 15.3% | $0 to $127,200 | 0% |

| $127,200 to $200,000 | 2.9% | $127,200 to $200,000 | 0% |

| $200,000 + | 3.8% | $200,000 + | 3.8% |

| Note: This calculation applies to a single filer who does not earn any wages or salary. | |||

In addition to these federal taxes, pass-through businesses are subject to state and local income taxes. Forty states and the District of Columbia levy state income taxes on pass-through businesses; the highest is California’s, with a top rate of 13.3 percent.

After all of these taxes combined, pass-through businesses can face a substantial marginal tax rate on their business income. For instance, a sole proprietor in California can be subject to a marginal tax rate as high as 51.8 percent (see table below).[15]

| Top marginal federal income tax | 39.6% |

| Top marginal state income tax | 13.3% |

| Federal self-employment tax | 3.8% |

| Adjustments for the state and local tax deduction, the deductible portion of the self-employment tax, and the Pease limitation | -4.9% |

| Total | 51.8% |

| Source: Author’s calculations | |

The top marginal tax rate on pass-through business income varies somewhat by state, ranging from 42.6 percent in ten states to 51.8 percent in California (Figure 5). The median state has a top marginal tax rate of 47.2 percent on sole proprietorship income. Weighted by the amount of pass-through business income in each state, the mean top marginal tax rate on sole proprietorships in the United States is 47.1 percent.

Figure 5.

The Case for the Current Tax Treatment of Pass-Through Business

Because pass-through businesses play such a large role in the U.S. economy, it is likely that the taxation of pass-through businesses will be a central focus of the tax reform debate in 2017 and beyond.

One question that federal lawmakers will face over the coming months is whether to raise or lower the seven individual tax rates on ordinary income (from 10 percent to 39.6 percent), and by how much. Because these rates apply to pass-through business income, they are the most important factor in determining the amount that pass-through businesses pay in federal income taxes.

However, in recent years, there have also been proposals to make more fundamental changes to the system of taxing pass-through businesses. Some scholars have called for taxing certain pass-through businesses as C corporations, meaning that some pass-through businesses would be subject to more than one layer of tax.[16] On the flip side, some policymakers have proposed creating a maximum tax rate for pass-through business income, meaning that some pass-through income would be taxed at lower rates than wages and salaries.[17]

Both of these proposals would be a sharp break from the last century of federal tax policy. Since the enactment of the federal income tax in 1913, income from pass-through businesses has been subject to a single layer of tax, at the same rates that apply to wages, salaries, and most other personal income.[18]

In general, lawmakers should be cautious about making fundamental changes to the tax treatment of pass-through businesses. This is because the current system of taxing pass-through businesses has several important, positive qualities.

The tax treatment of pass-through businesses is largely neutral, because pass-through business income is subject to the same income tax rates as most other personal income. In other words, the income tax code neither encourages nor discourages individuals from earning income from pass-through business activity, compared to other economic activities, for the most part.[19]

As a result, the current system of taxing pass-through businesses is also fairly efficient, because it allows individuals to choose whether to participate in pass-through businesses based on the economic merits, rather than based on tax considerations. In general, most economists agree that neutral tax systems are more economically efficient than tax systems that apply higher rates to specific activities.[20]

Finally, the tax treatment of pass-through businesses is relatively equitable, because households are taxed on their pass-through business income according to their overall tax bracket. Households with high incomes pay higher marginal income tax rates on their pass-through business income.

All in all, the current system for taxing pass-through businesses is designed well. Recent proposals to change how pass-through businesses are taxed would raise issues regarding neutrality, efficiency, and equity.

Taxing Some Pass-Through Businesses as C Corporations

It is easy to see why requiring some pass-through businesses to be taxed as C corporations would be a misguided approach. The tax treatment of C corporations is highly non-neutral, because the U.S. tax code imposes two layers of tax on corporate income, leading to an especially high top marginal tax rate on income from C corporations.[21] The corporate tax code is also quite inefficient, containing several well-known features that distort business decision-making, such as the bias towards debt financing over equity financing.[22] Finally, it is uncertain whether the corporate income tax even falls primarily on corporate shareholders, or whether it is largely borne by workers, making it difficult to determine whether the tax is equitable.[23]

Proponents of this approach argue that some pass-through businesses are just as large and economically significant as C corporations, and that there is little justification for creating two separate tax regimes for similar types of businesses. There is merit to this line of argument, but instead of forcing pass-throughs into the problematic double tax regime faced by C corporations, lawmakers should work to improve the C corporate tax regime, to move it closer to a single layer of tax at the same rates that apply to wages and salaries.[24] In short, the tax code should treat C corporations more like pass-through businesses, not the other way around.

Creating a Maximum Tax Rate on Pass-Through Business Income

Meanwhile, proposals to create a new, lower rate on pass-through businesses would also raise several concerns. Lawmakers would have to justify why income from pass-through businesses should be subject to a lower tax rate than income from wages and salaries. After all, taxing pass-through business income at a lower rate would make the U.S. tax code less neutral, potentially leading individuals to invest in pass-through businesses based on tax considerations, rather than the economic merits. In addition, this policy would only benefit pass-through business owners in the highest tax bracketsA tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. , creating equity concerns.

Furthermore, a lower tax rate on pass-through business income could create practical difficulties for tax administration. Because such a policy creates strong incentives to categorize as much income as possible as “pass-through business income,” it would have the potential to lead to substantial tax avoidance unless accompanied by strong anti-abuse rules.[25] In 2012, Kansas adopted a similar policy – a full exclusion of pass-through business income – which significantly narrowed the state’s tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. , due in part to increased opportunities for tax avoidance.[26]

Conclusion

It is clear that pass-through businesses play a significant role in the U.S. economy. Nine out of every ten companies in the United States are pass-through businesses; combined, they earn over half of all business income, and employ the majority of the private-sector workforce.

Although pass-through businesses are not subject to the federal corporate income tax, they can still face a substantial tax burden from federal, state, and local taxes. In most U.S. states, the top marginal tax rate on pass-through business income exceeds 47 percent.

As the tax reform debate moves forward in 2017, it will be important for policymakers to consider the effects of tax reform proposals on pass-through businesses. Lawmakers should keep in mind that the current system of taxing pass-through businesses is designed well, and they should be cautious about making fundamental changes to it.

Appendix A: The Concept of Tax Neutrality

The concept of tax neutrality can be confusing, and the term is sometimes used in different ways. This paper uses “neutral” to signify investment-consumption neutrality. The tax code is neutral toward a given class of investments if a household’s decision to undertake a marginal investment in that class is unaffected by tax considerations. Put another way, under a neutral tax code, a household would be indifferent between a) spending money on immediate consumption or b) investing the money in an asset that yields a return equal to the household’s discount rate.

To take a very easy example, the current income tax treatment of income from a bond held in a Roth IRA is perfectly neutral, because a household will pay exactly the same amount of federal income tax whether it invests $1,000 in the bond or whether it spends the money on consumption. The household’s decision about whether to consume or invest is entirely unaffected by tax considerations.

To determine whether lowering the tax rate on a given source of personal income would make the U.S. tax code more or less neutral, it is necessary to look at the overall tax treatment of that source of income under current law.

Creating a lower top rate on pass-through business income would likely be a move away from tax neutrality. This is because, under the current tax code, the tax treatment of pass-through business investment is already close to neutral. More precisely, the tax treatment of pass-through businesses would be perfectly neutral if pass-through businesses were able to expense the full cost of their capital investments. If expensing applied to all pass-through business investments, then households would be indifferent between consuming their income and investing it in a pass-through business at a normal rate of return.

By contrast, lowering the tax rate on long-term capital gains and qualified dividends would move the tax treatment of equity-financed C corporate investment closer to tax neutrality. This is because, under the current U.S. tax code, the tax treatment of corporate stock held in taxable accounts is quite far from neutral. Even with the current, lower rate schedule for long-term capital gains and qualified dividends, the top tax rate on C corporate equity is significantly higher than the top tax rate on wages and salaries, which gives households a significant incentive to consume their income, rather than investing in C corporate stock.

Appendix B: Supplemental Data on Pass-Through Businesses

[1] These categories do not always line up precisely with the business categories defined by state law. For instance, limited liability companies – a legal business form in all fifty states – can be classified as sole proprietorships, partnerships, S corporations, or C corporations for federal tax purposes, depending on the circumstances.

[2] However, there are certain cases in which pass-through businesses can be subject to entity-level income taxes, on both the federal and state levels. For instance, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 allowed the IRS to collect income taxes on partnership income at the firm level, in certain situations. In addition, S corporations are sometimes subject to entity-level income taxes levied by states.

[3] Here, “business” and “business establishment” are defined as “a single physical location at which business is conducted or services or industrial operations are performed.” See: U.S. Census Bureau, “Universe of County Business Patterns,” 2016, http://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cbp/technical-documentation/methodology/universe-of-cbp.html.

[4] Data compiled from U.S. Census Bureau, “County Business Patterns: 2014,” http://www.census.gov/data/datasets/2014/econ/cbp/2014-cbp.html; U.S. Census Bureau, “Nonemployer Statistics,” https://www.census.gov/econ/nonemployer/download.htm. “Private businesses” refers to all business establishments encompassed in these datasets, excluding “nonprofit,” “government,” and “other” establishments.

[5] Here, “workforce” is used to refer to the population of employed individuals, and does not include unemployed individuals seeking work.

[6] These figures may double count some individuals who were simultaneously self-employed as a sole proprietorship and employed by a different business as well.

[7] Internal Revenue Service, “SOI Tax Stats – Integrated Business Data,” Table 1, https://www.irs.gov/uac/soi-tax-stats-integrated-business-data.

[8] P.L. 99-514. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 also lowered the top corporate income tax rate from 46 percent to 34 percent. For a brief discussion of the effects of TRA86 on business forms, see: Congressional Budget Office, “Taxing Businesses Through the Individual Income Tax,” 2012, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/112th-congress-2011-2012/reports/43750-TaxingBusinesses2.pdf.

[9] Both figures are adjusted to 2015 dollars.

[10] Internal Revenue Service, “SOI Tax Stats – Integrated Business Data,” Table 1, https://www.irs.gov/uac/soi-tax-stats-integrated-business-data.

[11] 26 U.S.C. §1402

[12] This threshold is adjusted for inflation. Social Security Administration, “2017 Social Security Changes,” https://www.ssa.gov/news/press/factsheets/colafacts2017.pdf.

[13] This threshold is not adjusted for inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. .

[14] 26 U.S.C. §1411. The definition of “passive shareholder” is based on IRS guidelines regarding an owner’s level of participation in a business. Income earned by “active shareholders” of S corporations is not subject to self-employment taxes or the Net Investment Income Tax.

[15] The marginal tax rate on business income earned by a limited partner or passive S corporation shareholder can be even higher, because a portion of the self-employment tax is deductible from federal taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. Taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. , while no such deduction exists for any portion of the Net Investment Income Tax. In California, in 2017, the top marginal tax rate on a pass-through business income subject to the Net Investment Income Tax is 52.6 percent. On the other hand, the marginal tax rate on income earned by an active S corporation shareholder can be somewhat lower, because the income is neither subject to self-employment taxes nor the Net Investment Income Tax. In 2017, the top marginal tax rate on income earned by an active S corporation shareholder in California is 48.8 percent. See Appendix B, Table 1 for the top marginal tax rates on active and passive S corporation shareholders in each state.

[16] For instance, Alexandra Thornton and Brendan Duke, “Ending the Pass-Through Tax Loophole for Big Business,” Center for American Progress, 2016, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2016/08/10/139261/ending-the-pass-through-tax-loophole-for-big-business/.

[17] For instance, Main Street Fairness Act, H.R. 5076, 114th Cong. (2016).

[18] The Revenue Act of 1913 imposed one rate schedule on all personal income, including “the entire net income … of every business, trade, or profession.”

[19] See Appendix A for an extended discussion of tax neutrality, as applied to the current tax treatment of pass-through businesses.

[20] Pigouvian taxes are an exception to this general principle. Joel Slemrod, “Optimal Taxation and Optimal Tax Systems,” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 4 (1990): 157-178; Louis Kaplow, “On the Undesirability of Commodity Taxation Even When Income Taxation Is Not Optimal,” Journal of Public Economics 90 (2004): 1235-1250.

[21] See Scott Greenberg, “Corporate Integration: An Important Component of Tax Reform,” Tax Foundation, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/article/corporate-integration-important-component-tax-reform.

[22] See Eric Toder and Alan Viard, “Major Surgery Needed: A Call for Structural Reform of the U.S. Corporate Income Tax,” Tax Policy Center, 2014, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/major-surgery-needed-call-structural-reform-us-corporate-income-tax; Alan Cole, “Fixing the Corporate Income Tax,” Tax Foundation, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/article/fixing-corporate-income-tax.

[23] William M. Gentry, “A Review of the Evidence of the Incidence of the Corporate Income Tax,” Treasury Department, OTA Paper 101 (2007); Arnold C. Harberger, “Corporation Tax Incidence: What is Known, Unknown, and Unknowable,” Conference Paper, 2006, http://www.econ.ucla.edu/harberger/ah-corptax4-06.pdf.

[24] This general approach is known as corporate integration. See Scott Greenberg, “Corporate Integration: An Important Component of Tax Reform,” Tax Foundation, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/article/corporate-integration-important-component-tax-reform.

[25] One strong anti-abuse rule – stipulating that 70 percent of a pass-through business’s net income must be categorized as labor income – has been met with strong opposition from the pass-through business community.

[26] Scott Drenkard, “Kansas’ Pass-through Carve-out: A National Perspective,” Tax Foundation, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/article/kansas-pass-through-carve-out-national-perspective; Mark Robyn, “Not in Kansas Anymore: Income Taxes on Pass-Through Businesses Eliminated,” Tax Foundation, 2012, https://taxfoundation.org/article/not-kansas-anymore-income-taxes-pass-through-businesses-eliminated.