Tax Foundation Special Report No. 196

Key Findings

- 17 states taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. candy at a higher rate than other groceries, and four states collect an excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. on soda.

- In 2011, 14 states proposed new soda taxes (in some cases, raising product prices by as much as 264 percent). Two states proposed new candy taxes.

- Between 1998 and 2010, soda consumption per capita fell by 16 percent.

- Soda and candy taxes do not necessarily decrease caloric intake. One recent study finds that when adolescents switch away from soda due to price increases, the drop in calories is offset by an increase in calories consumed in other food and drink.

- Definitional problems plague the enforcement of and compliance with special taxes on candy and soda. For example, under many tax laws, a product with flour would be treated as food while a similar product without flour would be considered candy.

- Excise taxes on candy and soda fall on all individuals who consume the products, even those who do so moderately.

Introduction

In the past two decades nutritionists, biologists, and doctors have become increasingly interested in the causes and prevention of obesity. This fascination seems warranted; the incidence of obesity in adults jumped from 13 percent to 34 percent between 1962 and 2008, though it has since leveled off.[1]

Recently, this fervor has spilled over into the political scene as many politicians and some scientists make the case for government intervention to help trim the nation’s waistline. This desire has taken the form of proposals for taxes on fast food, salt, and vending machines, as well as outright bans on specific substances like trans fats. Some of these measures have been successful, while others have failed.

This report reviews some of the common arguments for and against the unequal taxation of different food items with the aim of curbing obesity. As a part of the analysis, we present an in-depth, up-to-date look at the progress of this type of legislation at the state and federal level, and offer suggestions for better ways to fight the obesity problem while avoiding the myriad problems that arise from attempts to do so through the tax code.

Obesity: “I Know It When I See It”?

The Centers for Disease Control defines an “obese” person as one who has a Body Mass Index (BMI) above 30. But what exactly does this mean? The Body Mass Index was first invented by Adolphe Quetelet in 1835. Quetelet was not a nutritionist or health expert, but rather a statistician who was expounding on the usefulness of the concept of “arithmetic mean.” He determined that, on average, “the weight increases as the square of the height.”

Over a century and a half later, Ancel Keys used the BMI as a loose corollary to health risks, a use which the statistician Quetelet could not have foreseen.[2] The linkage stuck, mostly because the needed data was so easy to collect.

One of the most criticized aspects of BMI is that it makes no distinction between mass which is fat and mass which is muscle. As a result, the measure is not a good indicator of health risk.[3] Often this means people who are in shape fall into the overweight or obese categories (see Table 2).

Many health professionals are urging researchers and doctors to start using waist measurements as a tool for analyzing patients’ optimal weight.[4] They say that while waist measurements also have drawbacks, they tend to give a better picture of weight-related health problems and are just as simple to collect as BMI figures.

Body Mass Index is the backbone of the data on obesity, and as we examine the case for obesity taxes, we will see that this flawed measurement technique can have profound effects on how economists and politicians attempt to set the tax rate on soda and candy.

What Is Candy?

Each state has a different definition of which products fall under the category of “candy” for the purposes of taxation, and these variations create complexity problems. These definitions are important because they determine which products will be taxed; this is known as the “base” of the sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. . In Colorado, New Jersey and other states, the definitions are fairly similar: “‘Candy’ means any preparation of sugar, honey, or other natural or artificial sweeteners in combination with chocolate, fruits, nuts or other ingredients or flavorings in the form of bars, drops, or pieces. ‘Candy’ does not include any preparation containing flour or requiring refrigeration.”[5]

Once a state has decided to treat candy differently from other groceries or other goods and services, this necessitates complex definitions and unequal treatment of specific products. Taxing all final retail sales equally and reducing rates overall could avoid these issues.

Singling out specific products to be excluded from or included in the sales tax base leads to a much more complex tax code, and the above definition of candy leads to tax compliance problems. Various snack bars have ingredient combinations that appear to fit under this definition of candy, but from a brief survey of grocery stores, we have determined that many stores incorrectly treat certain products as food rather than as candy.

While the above represents an instance where products are considered candy when they probably would not be colloquially called candy, there are also cases where products that people generally call candy do not meet the legal definition. Chocolate bars that include any form of flour, like Kit-Kat® and Twix®, which have a cookie inside, are not candy under this definition and are therefore exempt from a targeted tax.

The Streamlined Sales Tax Governing Board, a voluntary coalition of several states which was founded in an attempt to bring some uniformity and simplicity to state sales tax bases,[6] tried to address this definitional problem in August of 2010. They developed a six-page document outlining the proper definition of “candy,” where they targeted the definition of “flour” for clarification:

For purposes of the definition of candy, “flour” does not include a product that can be called “flour” under the Food and Drug Administration’s food labeling standards if the product is not grain based. If only the word “flour” is listed on the product label, it is assumed that the product contains grain based flour. However, if the word “flour” on the label is preceded by a modifier used to describe the product the “flour” was made from and the modifier is not a type of grain, then the product is not considered to contain “flour” for purposes of the definition of candy.[7]

These definitional contortions are necessary only because states treat products differently for sales tax purposes. Once a state has decided to treat candy differently from other groceries or other goods and services, this necessitates complex definitions and unequal treatment of specific products. Taxing all final retail sales equally and reducing rates overall could avoid these issues.[8]

What Is Soda?

Many states have hazy definitions of “soda” as well. In most states for the purposes of an excise tax (a tax levied on a specific product) sodas are officially called “caloric-sweetened beverages” or “soft drinks” and include some of the usual suspects like cola, root beer, ginger ale and lemon-lime carbonated drinks. But they also include any non-alcoholic beverage which is sweetened with a sucrose agent like sugar or high-fructose corn syrup.

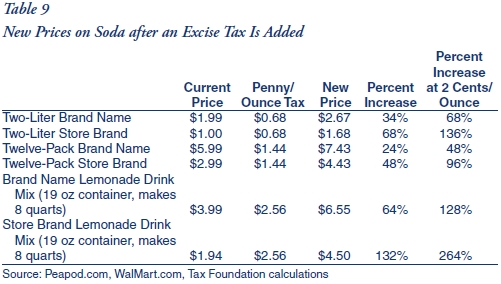

Most states also tax powder or syrup used to make sugar-sweetened beverages. Since the tax is levied on a per-ounce basis, they tax it according to how much soda or beverage the powder or syrup yields. This can result in hefty taxes on popular drink mixes like lemonade (see Table 9).

In California and Arkansas, beverages must have at least 10 percent fruit juice before they are exempt from the proposed excise tax. In Rhode Island, substances with 50 percent fruit juice are exempt. In Tennessee, Oregon and Texas, the standard is even stricter: products must be 100 percent fruit or vegetable juice to be exempt. This means that even some of the products from the V8® line of juices are taxable.

In almost all states considering soda excise taxes, popular hydration drinks like Gatorade® and Vitamin Water® would be taxable under the proposed bills. The Texas bill is the only one to exempt sports drinks.

Notably, in all the states that already have a soda excise tax-West Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and Virginia-diet sodas are subject to the tax.[9] Many of the new bills, however, would exempt diet sodas.[10]

The Frappuccino® Test

While most people can easily name some beverages that are considered “soft drinks,” there are some surprising products that fall into this category. One example of the confusion over definitions is the case of bottled Frappuccino® beverages. Frappuccino® is often exempt because of its coffee content (California), milk content (Oregon, Arkansas, Rhode Island[11]), or non-carbonated nature (Virginia).

Most states exempt milk, baby formulas, weight loss beverages, medical food, coffee and tea. In Alabama, the law even makes a point of excluding bitters and clam juice from the definition of soda. In Texas, Tennessee and Illinois, any bottled coffee or tea product to which sugar is added is subject to an excise tax, unless the product has a certain amount of milk, in which case it is exempt.

Soda and Candy Taxes: A History

In 2009, in an effort to find different ways to fund the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, federal lawmakers drew up plans for a national excise tax on soda. Though no specific rate was ever proposed, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that taxing soda at a rate of 3 cents per 12-ounce serving could generate over $24 billion in four years.[12] When that measure fell flat due to overwhelming opposition at the federal level, state legislatures took up the idea. In the 2011 session, 14 states considered proposals to enact excise taxes on soda with the intention of trimming the nation’s waistline, and four states already collect some form of excise tax. In the war against obesity, soda seems to be the first political target.

National soda and candy tax schemes have been tried before in the United States, and they tend to crop up during times of governmental penny-pinching. In 1917, the first tax to affect the sweets market was passed as part of a World War I tax package, and was levied on the ingredients used in soda production. An excise tax on sugar at the rate of one-half penny per pound was also originally included as a part of the bill, but was omitted from the final version.[13] In 1919, a 10 percent manufacturer’s tax was levied on bottled sodas, and a 10 percent retail tax on soda fountain sales. This measure was also pushed through Congress under the auspices of helping the war effort, though the bill actually passed three months after the armistice was declared.[14]

In the war against obesity, soda seems to be the first political target.

At this time, sweets were not being vilified as the culprit of an obesity pandemic, but instead were seen as a non-necessity, even a luxury, that people ought to pay more for to help the war effort. The “beverage” tax, which was levied on such dissimilar items as ice cream, egg creams, and ginger beer, was hard to collect. “The law says cold malted milk is a beverage and subject to tax,” read a Los Angeles Times article, but “hot malted milk is a food and is exempt.”[15]

Drug store owners formed the Soda Fountain Association, and managed to get the tax repealed in 1922. However, in 1932, a similar tax was instituted, driven by “the continued general economic deterioration, the growth of deficits, […] and the consequent need for still more revenue.” Candy and chewing gum were taxed at 2 percent and soft drinks at various rates. The tax was expected to raise $12 million in the next year,[16] but it was short-lived, like the tax that had preceded it, and was overturned in two years because of unpopularity and low revenue collection.[17]

Recent Proposals for Soda and Candy Taxes

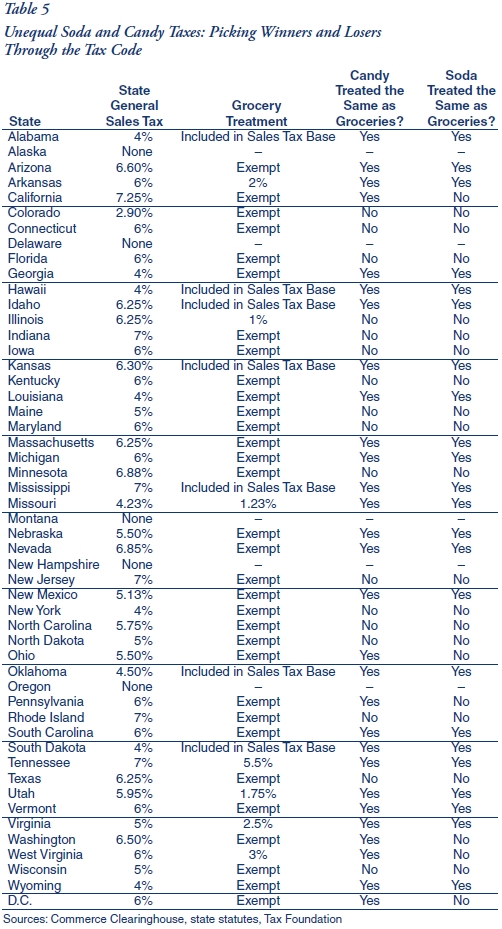

Table 5 shows tax rates on grocery products in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. Of the 45 states that have a sales tax, 31 of them give groceries an “exempt” status, and seven tax groceries at a lower rate than their general sales tax.

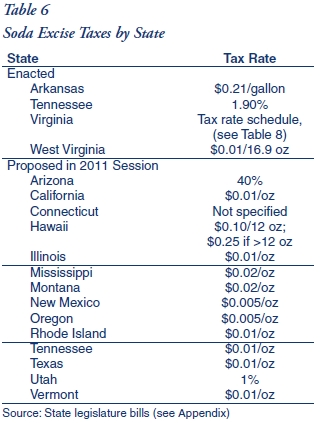

This tax break does not extend to all products though. Seventeen of the states that exempt groceries from sales tax exclude candy from the “groceries” definition and tax it at the general sales tax rate. Twenty-two states and D.C. do the same for soda. Four states go even further and place an excise tax on soda: Arkansas, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia. These taxes are levied in a variety of ways; Arkansas and West Virginia levy the tax based on volume, while Tennessee has a gross receipts tax on soda at the rate of 1.9 percent. Virginia has a strange rate which is determined by a rate schedule (see Table 8).

In addition to collecting a 1.9 percent manufacturer’s tax on soda, Tennessee is also one of 14 states considering a new excise tax on soda (see Table 6). These newly introduced bills aim to tax soda at a much higher rate than the states that already implement soda taxes. Most propose a rate of $0.01/ounce, but Mississippi and Montana propose the even heftier rate of $0.02/ounce. For store brand two-liter sodas at current prices, this amounts to a 136 percent tax.

However, not all new soda excise tax proposals would tax the sugary beverages based on volume. In the 2011 session, Arizona proposed a 40 percent tax on all receipts from soda and Utah proposed a 1 percent soda sales tax. Connecticut issued a bill that did not even set a rate.

While many states are proposing new excise taxes for soda and candy, other states that had them have voted them out of existence. Maine and Washington have both recently repealed excise taxes on soda and candy through an initiative process. In November of 2008, Maine voters repealed the soda excise tax (4 cents per 12-ounce can) through a landslide vote: 65 percent versus 35 percent.[18] Also included in the tax rollback was a repeal of excise tax hikes on wine and beer: seven cents per bottle of wine and 16 cents per six pack of beer.[19] In November of the same year, the state of Washington had a similar repeal: 63 percent voted for an initiative that turned over an unequal sales tax treatment on candy and a 2 cent-per-12 ounce excise tax on soda.[20]

Economists and policymakers sometimes support governmental intervention to correct for externality problems, but in the case of soda and candy taxation, the logic is flimsy.

Many bills have been introduced repeatedly in recent years, despite unpopular reception. In Mississippi, a bill that called for a tax of two cents per ounce expired in committee in February 2010, but Representative John Mayo said he had high hopes for reintroducing the issue: “This is just the first bat in the first inning. We expect this to be a long haul. I never expected the issue to get this much buzz the first time out. It shows the passion people have over this issue.”[21] Mayo introduced virtually the same bill in the 2011 session.

Other notable action for soda taxA soda tax, often discussed under a broader policy category of a sugar-sweetened beverage tax, is an excise tax on sugary drinks. Most soda taxes apply a flat rate tax per ounce of a sugar-sweetened beverage, though some jurisdictions levy an ad valorem tax based on the beverage’s price. bills has been widespread. For example, a New Hampshire bill that proposed a one-cent-per-ounce rate expired in committee in 2010,[22] and in New York, Governor Paterson proposed an unsuccessful 15 percent tax on non-diet sodas in 2008.[23]

This analysis suggests that excise taxes on soda and candy are an increasingly attractive source of revenue for tax collectors. With 22 states having recent experience with a soda excise tax in some form or another, the issue is likely to be an important legislative debate for years to come.

With 22 states having recent experience with a soda excise tax in some form or another, the issue is likely to be an important legislative debate for years to come.

Four states-Massachusetts, Oregon, New York, and Vermont-proposed candy tax changes in 2011 (see Table 7). Massachusetts and Vermont proposed to start taxing candy and soda at the general sales tax rate, and the bills in Oregon and New York proposed rates above the sales tax.

The ExternalityAn externality, in economic terms, is a side effect or consequence of an activity that is not reflected in the cost of that activity, and not primarily borne by those directly involved in said activity. Externalities can be caused by either the production or consumption of a good or service and can be positive or negative. Myth

People sometimes engage in actions that create side effects for others in the economy. These side effects are called “externalities,” because they shift a cost or benefit of an action away from decision-makers and onto some external party. The classic example of an externality problem is a paper factory that expels fumes into the air while producing paper. While the company may enjoy the benefits of profits from their sale of paper, they shift some of the costs of paper production onto the rest of society in the form of increased pollution.[24]

Economists and policymakers sometimes support governmental intervention to correct for externality problems, but in the case of soda and candy taxation, the logic is flimsy. According to proponents of taxes on soda and candy, obese people create a negative externality because they get sick more often. Some estimate that obesity and overweight problems account for 9.1 percent of all health care costs in the U.S. This amounts to $147 billion, with one half of that amount being paid for by Medicare and Medicaid.[25]

Therefore, proponents claim, taxpayers and insurance holders pay for the actions of obese people in the form of higher entitlement spending for Medicare and Medicaid recipients, or in the form of higher premiums for anyone who happens to share a private insurance risk pool with obese people. This allegedly means that levying a tax directly on the obese people who are projecting externalities onto the rest of society would cause them to “internalize the costs” of their actions.

Of course, taxes on soda and candy would not reasonably address the obesity problem under these criteria. Instead of taxing obesity directly as mandated by economic theory, they would only tax potential causes of obesity in the form of candy and soda. In short, obese people may create an externality, but candy and soda do not necessarily do so. Some have said that if proponents of a soda tax really wanted to help internalize the social costs of obesity, they ought to tax obesity directly rather than tax arbitrarily chosen products like soda and candy. (Of course this would not be politically feasible or desireable.) In a tongue-and-cheek commentary, Will Wilkinson noted:

If public health is the role of government, let’s not get bogged down in this nonsense about rigging the relative prices of arugula and Ho-Hos. Let’s just raise the price of being unhealthy… I modestly propose Americans be made to file an annual health auditA tax audit is when the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) or a state or local revenue agency conducts a formal investigation of financial information to verify an individual or corporation has accurately reported and paid their taxes. Selection can be at random, or due to unusual deductions or income reported on a tax return. with the Department of Health and Human Services for the purpose of assessing health-related tax credits and penalties.[26]

Furthermore, not all externalities signify market failure. The “cost shifting” caused by obesity seems to persist only as a result of government interference. In many cases, the only reason that an externality exists is because Medicare and Medicaid by definition shift the cost of health care from individuals to federal taxpayers.

In addition, Marlow and Shiers (2010) find that the only reason private markets are not able to correct for externality problems related to obesity is because they are hamstrung by government regulations:

The problem with the externality argument is that, even if obesity raises health care costs of the obese, this externality should be corrected by having health insurers impose surcharges on obese insureds that reflect the additional costs. Few criticize surcharges imposed by auto insurance firms on drivers with drunk driving records, so why not correct for higher costs associated with obesity through insurance premiums? Unfortunately, federal health care legislation passed earlier this year severely reduces or eliminates differential health insurance pricing.[27]

|

Tax or Fee? Is a government-imposed charge on candy or soda a tax or a fee? In Hawaii similar proposals to impose a charge on sugary beverages were called a fee in two bills (H.B. 1062 and H.B. 1188) but a tax in two others (H.B. 1179 and H.B. 1216). While both taxes and fees raise revenue from the government and have similar economic effects, using the “fee” label instead of the “tax” label can have significant political and legal results. |

These are not just different labels for identical revenue categories but rather two different models for government revenue. In both cases, a payer makes a voluntary decision to engage in an activity (earning income, buying gasoline, buying a plastic bag, entering a park) but in neither case is the charge itself voluntary. (A voluntary gift to government programs, which some state income tax forms allow, would be a donation.)

Most candy and soda tax proposals direct the revenue to general government spending, even if it is targeted for obesity prevention or health promotion. These activities are services available to the general population and are not provided specifically to the payers of the charge. Therefore, revenue raised by imposing a charge on candy or soda is properly called a tax.

Academic Research on Impact of “Sin Taxes” Is Unsettling

Excise Taxes Often Fail to Produce Desired Behavior Changes

A careful reading of the literature on “sin taxes” suggests that not only do excise taxes have unintended consequences; they are often completely ineffective at bringing about the desired behavior change. Psychologist Kelly D. Brownell is the Director of the Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity.[28] He coauthored a seminal article in 2009 which calls for an excise tax on soda at a rate of one cent per ounce, the same rate later proposed by bills in California, Illinois, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas, and Vermont.[29] He touts the proposed revenues of a national tax on soda at that rate: $14.9 billion.

Brownell cites many useful consumption figures in this article, but one very important statistic is misleading. While Brownell states that “between 1977 and 2002, the per capita intake of caloric beverages doubled in the United States across all age groups,” he doesn’t mention that in more recent years (1998 to 2010) U.S. per capita soda consumption has actually fallen by over 16 percent.[30] This data suggests that consumers may be moving away from soda without the help of excise taxes.

Under a new tax regime, we might see soda manufacturers advertise their brand as the highest in caffeine or sugar, in a sort of “more bang for your buck” approach.

Further, the exact impacts of excise taxation on individual behavior are still debated. Brownell’s article uses elasticity analysis to claim that a one-cent-per-ounce tax on sodas will increase the price of soda by 15 to 20 percent, and with a 25 percent “substitution effect,” that will equal a 10 percent decrease in total caloric consumption. In layman’s terms, the article is making three claims: 1) An increase in price will lead to a decrease in consumption of soda; 2) only 25 percent of the consumers who stop buying soda because of the new tax will substitute some other calorie source for soda; and 3) this will lead to a 10 percent decrease in caloric consumption on average.

Economist Jason Fletcher, a colleague of Brownell, has discredited the second claim. Using consumption and calorie data (which is regrettably absent from Brownell’s analysis), Fletcher argues that while soda taxes certainly decrease child and adolescent consumption of sugary beverages, the rate at which they do so is subject to dispute. “There is a relatively large range of uncertainty for policy makers to predict demand responses to price changes given the evidence accumulated thus far.”[31]

A two-liter bottle of store brand soda would be 68 percent more expensive under the proposed bills. Store brand lemonade drink mix would see a price increase of 132 percent. If the levy is set at two cents per ounce, as proposed in Mississippi and Montana, the rate doubles to 264 percent.

Furthermore, Fletcher’s analysis concludes that when adolescents stop drinking soda due to price increases, the decrease in calories consumed is completely offset by increases in calories consumed from other beverages. This means that the “substitution effect” may very well be 100 percent, which is known as “perfect substitution,” as children and adolescents tend to replace soda with juice drinks and milk as the price of soda rises. If anything, this could lead to weight gain, as some beverages have more calories than soda.[32]

Excise Taxes Often Have Unforeseen Negative Effects

Public policies often have unintended consequences that outweigh their benefits. In the case of cigarette taxation, some of the results are more far-flung than policymakers could have imagined. Adams and Cotti (2008) show that smoking bans in bars have led to increases in fatal car accidents because smokers must travel farther to bars that allow smoking.[33]

Fleenor (2006) found that excessive cigarette taxes in California led to $4.3 million in lost revenue, as smugglers would buy packs in South Carolina to sell at discounted prices in California. The excise tax was so great that it even spurred violent crime:

On the morning of December 15, 2002, a band of robbers burst into a Merced distribution center and rounded its employees up at gunpoint. After tying up the workers the thieves used forklifts to load pallets of cigarettes into a truck. The robbers then grabbed rolls of California cigarette tax stamps and fled. Police estimated that the group made off with more than $1 million in loot.[34]

LaFaive and Nesbit (2010), found that smuggled cigarettes account for substantial portions of the cigarettes consumed in each state. In Arizona, over half of all cigarettes consumed come from smuggled sources.[35]

Excise taxes are different from other taxes in that they have two goals: raise revenue and discourage consumption. This is a win-win for politicians, because after the fact, they can always claim success.

Adda and Cornaglia (1996) have concluded that increases in the price of cigarettes due to excise taxes led smokers to select cigarettes with higher tar and nicotine content or just to change their behavior and smoke cigarettes more “intensely.”[36]

It seems entirely plausible that a new type of drink could emerge from manipulation of soda prices. Under a new tax regime, we might see soda manufacturers advertise their brand as the highest in caffeine or sugar, in a sort of “more bang for your buck” approach. It seems equally likely that servings would get smaller and more concentrated to avoid taxation on a per-ounce basis. Energy drinks would likely become more popular.[37]

Politically Expedient, but Still Poor Tax Policy

Excise taxes are different from other taxes in that they have two goals: raise revenue and discourage consumption. This is a win-win for politicians, because after the fact, they can always claim success. If the tax is particularly bad at garnishing stable revenue, supporters are able to claim that the tax did a good job of discouraging behavior, and vice versa.

Surveys also suggest that soda taxes are only popular when coupled with some other favorable policy. A poll of New Yorkers showed that 66 percent of people oppose soda taxes in general, but when they are told the revenue will go toward health care costs, they respond differently: 49 percent oppose the bill and 48 percent support it.[38]

Not surprisingly, many of the soda tax bills currently under consideration would allocate part of the revenue for health care and education programs, some of which would have Orwellian names. In Illinois, 50 percent of the tax revenue is allocated to the newly created “Illinois Health Promotion Fund,” which is a trust fund to give grants and host child obesity prevention programs. In Hawaii, the levy is called the “Sugary Beverage Healthy Hawaii Fee.” However, a bad idea, no matter how it is bundled and sold, remains a bad idea.

Proponents of obesity taxation argue that they are helping to internalize externalities, yet what they really do is unfairly burden all who enjoy soda and candy, regardless of what might be otherwise very healthy lifestyle habits.

Soda Tax Rates Could Increase to 264 Percent

While the proposed soda taxes in many states are levied at a “penny per ounce,” it takes some effort to convert this into an easily understandable effective tax rate. Assuming pre-tax prices remain contant, a two liter bottle of store brand soda would be 68 percent more expensive under the new proposed bills. Store brand lemonade drink mix would see a price increase of 132 percent (see Table 8).

If the levy is set at two cents per ounce, as proposed in Mississippi and Montana, the rate doubles to 264 percent. To put things in perspective, the state of Washington levies the highest state-level excise tax on gasoline at a rate of $0.375 per gallon.[39] The “penny per ounce” soda tax is over three times as high, at $1.28 per gallon.

Throwing out the Baby with the Bath Water

Proponents of a soda excise tax claim that soda consumption is linked to obesity. In a 2007 meta-analysis of existing studies, Vartanian et al. conclude that soda intake is clearly linked to increased “energy” intake and body weight. In short, those who drink more soda tend to be more obese.[40]

That said, one can drink soda without being obese. Many people with a “healthy” Body Mass Index enjoy the occasional soda or candy bar-maybe even one per day-and do not become obese. They modify their calorie intake elsewhere, or balance their diet with more exercise. However, an excise tax on soda or candy punishes these people, too, which raises questions of equity within the tax code.

The solution to the obesity problem will not come from abdicating personal decisions like eating choices to government. It will come from consumers making prudent decisions about their own diets, exercise and health needs.

A point made by many economists that is often overlooked in the health literature is that any social welfare gains from soda and candy taxes reducing obesity would be offset by the welfare loss of higher taxes on non-obese soda drinkers. Setting the tax at an arbitrary rate (as appears to be the case in every state) makes it likely that society will be worse off as a result of the taxes.

Regressivity and Neutrality

The primary purpose of taxes is to raise revenue for necessary government services, not to change behavior. Therefore, the tax code should not discriminate against certain groups of people and favor others. Soda and candy taxes aim to change the behavior of obese people, but the consequences of soda taxation are more discriminatory than what first meets the eye.

Many people claim that taxes on soda and candy would be regressive, meaning that lower-income individuals would bear a disproportionate share of the tax burden, and we cannot know how a tax will affect each income group until it is instituted. We do know that people with lower incomes spend a larger portion of their earnings on groceries than people in higher income groups.[41] Schurtleff (2009) found that the bottom quintile of income earners already pay the largest share of their income in excise taxes: 1.9 percent in 2006, compared to 0.4 percent for the top quintile.[42]

Simplicity and Stability

In addition to creating confusing definitional problems, excise taxes on a new product increase tax complexity because they require a new structure of collection that must be planned and executed by tax collection authorities. Adding new excise taxes on soda and candy, as opposed to changing current tax rates (which would require no new overhead), would increase tax agencies’ administrative costs. An egregious example of this occurs in Tennessee, which is considering a penny-per-ounce soda excise tax even though they already have a 1.9 percent gross receipts taxGross receipts taxes are applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like compensation, costs of goods sold, and overhead costs. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and applies to transactions at every stage of the production process, leading to tax pyramiding. on soda at the wholesale level. Both of these taxes achieve the desired goal of a price increase; there is no need to levy two separate taxes.

Conclusion

Singling out soda and candy for taxation is a poor method of combating obesity. Proponents of obesity taxation argue that they are helping to internalize externalities, yet what they really do is unfairly burden all who enjoy soda and candy, regardless of what might be otherwise very healthy lifestyle habits.

Further, taxes like this tend to have unintended consequences. Detailed economic analysis shows that when the consumption of soda is discouraged with higher prices, children and adolescents tend to substitute other food or drink to make up for lost calories. Taxes on soda could even cause an increase in caloric consumption, as other substitutes can have higher calorie contents than soda.

The solution to the obesity problem will not come from abdicating personal decisions like eating choices to government. It will come from consumers making prudent decisions about their own diets, exercise and health needs.

Appendix

Enacted Soda Taxes:

W. Va. Code § 11-19-1 (2010).

23 Va. Admin. Code § 10-390-20 et seq. (1985).

Va. Code Ann. § 58.1-1700 et seq. (1984).

Tenn. Code Ann. § 67-4-402 (1999).

006-05-203 Ark. Code R. § 203 (1993) (amended 2008).

Proposed Soda Taxes:

S. A. 1210, 2009-2010 Reg. Sess. (Ca. 2010).

A. B. 669, 2011-2012 Reg. Sess. (Ca. 2011).

H.R. 2214, 82d Leg., Reg. Sess. (Tex. 2011).

H.R. 537, 107th Leg., 1st Reg. Sess. (Tenn. 2011).

H.R. 5432, 2011 Leg., Jan. Sess. (R.I. 2011).

H.R. 2644, 7th Leg., Reg. Sess. (Or. 2011).

S. 396, 97th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Ill. 2011).

S. 256, 2011 Leg., Jan. Sess. (Conn. 2011).

State Assemb. 669, 2011-2012 Leg., Reg. Sess. (Cal. 2011).

Vt. H. 151, 2011 Sess.

Ariz. H.B. 2643, 2011 Sess.

N.M. S.B. 288, 2011 Sess.

Miss. S.B. 2678, 2011 Sess.

Miss. H.B. 414, 2011 Sess.

Mont. H.B. ____, 62nd Sess. (2011). (imposing a $0.02/ounce excise tax on sugar sweetened beverages. Discussed widely but never introduced)

Utah H.B. 426, 2011 Sess.

Hawaii H.B. 1188, 2011 Sess.

Hawaii H.B. 1062, 2011 Sess.

Hawaii H.B. 1216, 2011 Sess.

Hawaii H.B. 1179, 2011 Sess.

Proposed Candy Taxes:

Mass. H.B. 1697, 2011 Sess.

Ore. S.J.R. 29., 2011 Sess.

Vt. H.B. 146, 2011 Sess.

Vt. H.B. 98, 2011 Sess.

N.Y. A.B. 843, 2011 Sess.

The author would like to thank Jason Sapia for his assistance on this report.

[1] Cynthia L. Ogden and Margaret D. Carroll, Prevalence of Overweight, Obesity, and Extreme Obesity Among Adults: United States, Trends 1960-1962 Through 2007-2008. National Center for Health Statistics, Center for Disease Control and Prevention. June 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/NCHS/data/hestat/obesity_adult_07_08/obesity_adult_07_08.pdf.

[2] Garabed Eknoyan, “Adolphe Quetelet (1796-1874) the average man and indices of obesity,” Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, Oct. 19, 2007. http://ndt.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2007/10/19/ndt.gfm517.full.pdf+html.

[3] Gill M. Price, Ricardo Uauy, et al., “Weight, shape, and mortality risk in older persons: elevated waist-hip ratio, not high body mass index, is associated with a greater risk of death,” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 84: 449, http://www.ajcn.org/content/84/2/449.full.pdf+html.

[4] D.C. Chan et al. “Waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio and body mass index as predictors of adipose tissue compartments in men,” QJM (2003) 96 (6): 441-447. http://qjmed.oxfordjournals.org/content/96/6/441.abstract.

[5] N.J. Stat. Ann. 54:32B-82(c) (West 2008); Colo. Rev. Stat. § 39-26-707(1.5)(b)(West 2010).

[6] The Streamlined Sales Tax Project often causes more problems than it solves. See Mark Robyn, “The Streamlined Sales Tax Project Can’t Get No Respect.” Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog. February 24, 2011. http://www.taxfoundation.org/legacy/show/27070.html.

[7] Streamlined Sales Tax Board. For August 26 SLAC Teleconference. Rule 327.6 Food and Food Ingredients Definitions. August 25, 2010. http://www.streamlinedsalestax.org/uploads/downloads/SLAC%20Meeting%20Materials/2010/SL10046_Rule%20327%20_%20Candy%20_%20Draft%20for%208_26_10%20SLAC%20 Teleconference.pdf.

[8] See William Ahern, “What’s Wrong with California’s Sales Tax ExemptionA tax exemption excludes certain income, revenue, or even taxpayers from tax altogether. For example, nonprofits that fulfill certain requirements are granted tax-exempt status by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), preventing them from having to pay income tax. for Groceries?” Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog. December 31, 2008. http://www.taxfoundation.org/legacy/show/24142.html

[9] The Virginia tax does not even provide a definition of “soft drink” in its Administrative Code.

[10] See H.R. 537, 107th Leg., 1st Reg. Sess. (Tenn. 2011). Tennessee’s attempt to exempt diet sodas has a potential for abuse. Subsection C of the bill states, “Any bottled soft drinks that contain less than one (1) calorie per fluid ounce or that contain non-caloric sweetener shall be exempt from the tax provided in subsection (b),” but the bill makes no judgment as to what quantity of non-caloric sweetener must be added to the soda before it is tax-exempt. It is not hard to imagine beverage companies adding a trivial amount of sucralose or aspartame to their otherwise non-diet sodas and then claiming an exemption.

[11] If not for the milk in Frappuccino®, it would be taxable in Rhode Island and Arkansas.

[12] Jane Adamy, “Soda Tax Weighed to Pay for Health Care.” the Wall Street Journal. May 12, 2009. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB124208505896608647.html.

[13] F. W. Taussig, “The War Tax Act of 1917,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics. Vol. 32, No. 1 (Nov. 1917), pp.1-37. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1885077.

[14] Roy G. Blakey and Gladys C. Blakey, “The Revenue Act of 1918,” The American Economic Review, vol. 9, no. 2 (Jun., 1919), pp.214-243. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/1823605

[15] Joseph J. Thorndike, News Analysis: Pop Goes the Soda Tax. Tax Analysts. May 21, 2009. http://www.taxhistory.org/thp/readings.nsf/ArtWeb/186B22AE29FA8E15852575CA00439846?OpenDocument.

[16] Roy G. Blakey and Gladys C. Blakey,. ” The Revenue Act of 1932,” The American Economic Review, vol. 22, no. 4 (Dec. 1932), pp. 620-40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1805167.

[17] Joseph J. Thorndike. Ibid.

[18] November 2, 2010 General Election Results. Washington Secretary of State website. http://vote.wa.gov/results/20101102/Initiative-Measure-1107-Concerns-reversing-certain-2010-amendments-to-state-tax-laws.html.

[19] Susan M., “Voters strongly support beverage tax repeal,” The Portland Press Herald, March 13, 2010. http://www.pressherald.com/archive/voters-strongly-support-beverage-tax-repeal_2008-11-04.html.

[20] November 2, 2010 General Election Results. Washington Secretary of State website. –http://vote.wa.gov/results/20101102/Initiative-Measure-1107-Concerns-reversing-certain-2010-amendments-to-state-tax-laws.html.

[21] Adam Lynch, “Bashing Sodas and Saving Schools,” Jackson Free Press. February 24, 2010. http://www.jacksonfreepress.com/index.php/site/comments/bashing_sodas_and_saving_schools_022410.

[22] H.R. 1679, 2010 Leg., 161st Sess. (N.H. 2010)

[23] Glenn Blain and Kenneth Lovett, “Governor Paterson proposes ‘Obesity Tax,’ a tax on non-diet sodas.” New York Daily News. December 14, 2008. http://www.nydailynews.com/ny_local/2008/12/14/2008-12-14_governor_paterson_proposes_obesity_tax_a-1.html.

[24] Bryan Caplan, “Externalities.” The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/Externalities.html.

[25] E.A. Finkelstein, and F.G. Trogdon et. al. Annual Medical Spending Attributable to Obesity: Payer and Service Specific Estimates. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:w822-w831.

[26] Will Wilkinson, “Tax the Fat, Not Their Food,” The Economist online. July 26, 2011 http://www.economist.com/node/21524522.

[27] Michael L. Marlow and Alden F. Shiers, “Would Soda Taxes Really Yield Health Benefits?” Regulation, Fall 2010.

[28] Yale Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity website. Faculty and Administration. http://www.yaleruddcenter.org/who_we_are.aspx?id=11.

[29] Kelly Brownell, et al. “The Public Health and Economic Benefits of Taxing Sugar-Sweetened Beverages,” The New England Journal of Medicine 2009:361; 1599-1605. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMhpr0905723.

[30] John Sicher, ed. “Top 10 CSD Results for 2010,” Beverage Digest. March 11 2011. http://www.beverage-digest.com/pdf/top-10_2011.pdf.

[31] Jason Fletcher, et. al. “The Effects of Soft Drink Taxes on Child and Adolescent Consumption and Weight Outcomes.” Journal of Public Economics.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Scott Adams and Chad Cotti, “Drunk Driving After the Passage of Smoking Bans in Bars.” Journal of Public Economics 92 (5-6), 1288-1305. 2008.

[34] Patrick Fleenor, “California Schemin’: Cigarette Tax Evasion and Crime in the Golden State.” Tax Foundation Special Report No. 145. October 2006. https://taxfoundation.org/files/sr145.pdf.

[35] Michael LaFaive and Todd Nesbit, Cigarette Taxes and Smuggling 2010. Mackinac Center for Public Policy. 2010

[36] Jerome Adda and Francesca Cornaglia, “Taxes, Cigarette Consumption and Smoking Intensity.” American Economic Review. 96 (4), 1013-1028.

[37] This assertion is supported by the Alchian-Allen Theorem, which states that as the price of two substitute products is increased by a fixed amount, consumption will flow to the higher quality product. See: Armen A. Alchian and William R. Allen, University Economics. Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth, 1964, and later eds.

[38] Bruce Drake, “Tax Sugary Drinks? New Yorkers Say ‘No’ but Leave Some Wiggle Room.” Politics Daily. http://www.politicsdaily.com/2010/04/14/n/.

[39] “State Gasoline Tax Rates, as of January 1, 2011,” Tax Foundation. February 25, 2011. http://www.taxfoundation.org/legacy/show/26079.html.

[40] Lenny R. Vartanian, Marlene B. Schwartz and Kelly D. Brownell. “Effects of Soft Drink Consumption on Nutrition and Health: A Systematic Review and Meeta- Analysis.” American Journal of Public Health. April 2007, Vol. 97, No. 4.

[41] Consumer Expenditure Survey, Expenditure Shares Tables. Bureau of Labor Statistics. http://bls.gov/cex/csxshare.htm.

[42] D. Sean Schurtleff, “Not So Sweet Excise Taxes.” Brief Analysis No. 663. National Center for Policy Analysis. July 1, 2009. http://www.ncpa.org/pub/ba663.

Share this article