Last Updated August 23, 2021

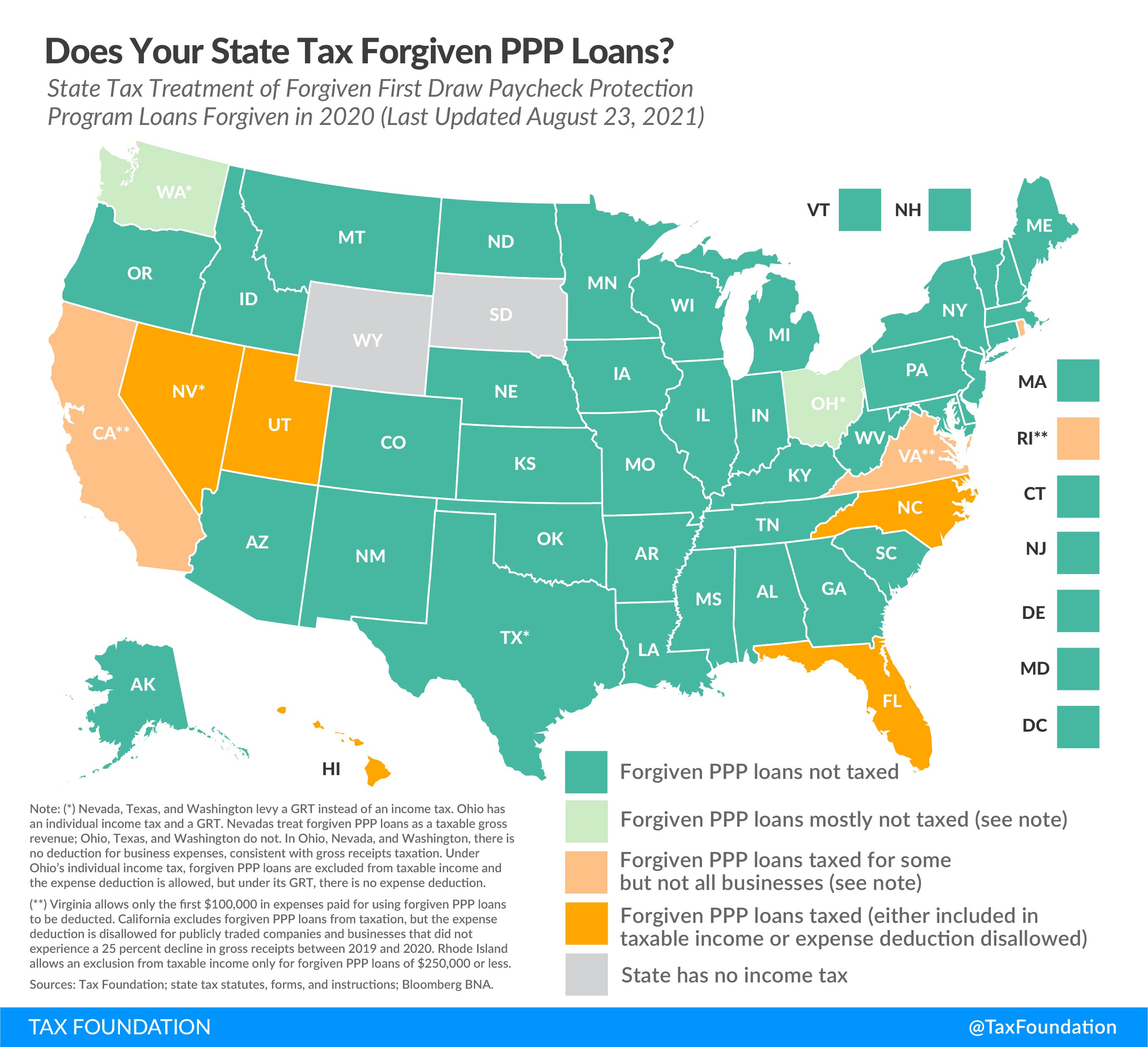

Note: The map and table below show state tax treatment of PPP loans forgiven in 2020, not necessarily those forgiven in 2021. While most states are on track to apply consistent taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. treatment to loans forgiven in 2020 and 2021, that is not the case in all states.

The U.S. Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) is providing an important lifeline to help keep millions of small businesses open and their workers employed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many borrowers will have these loans forgiven; eligibility for forgiveness requires using the loan for qualifying purposes (like payroll costs, mortgage interest payments, rent, and utilities) within a specified amount of time. Ordinarily, a forgiven loan qualifies as income. However, Congress chose to exempt forgiven PPP loans from federal income taxation. Many states, however, remain on track to tax them by either treating forgiven loans as taxable income, denying the deduction for expenses paid for using forgiven loans, or both. The map and table below show states’ tax treatment of forgiven PPP loans.

| State | Excludes from Taxable Income | Allows Expense Deduction |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | ✔ | ✔ |

| Alaska | ✔ | ✔ |

| Arizona | ✔ | ✔ |

| Arkansas | ✔ | ✔ |

| California** | ✔ | Deductible for Some Businesses |

| Colorado | ✔ | ✔ |

| Connecticut | ✔ | ✔ |

| Delaware | ✔ | ✔ |

| Florida | ✔ | |

| Georgia | ✔ | ✔ |

| Hawaii | ✔ | |

| Idaho | ✔ | ✔ |

| Illinois | ✔ | ✔ |

| Indiana | ✔ | ✔ |

| Iowa | ✔ | ✔ |

| Kansas | ✔ | ✔ |

| Kentucky | ✔ | ✔ |

| Louisiana | ✔ | ✔ |

| Maine | ✔ | ✔ |

| Maryland | ✔ | ✔ |

| Massachusetts | ✔ | ✔ |

| Michigan | ✔ | ✔ |

| Minnesota | ✔ | ✔ |

| Mississippi | ✔ | ✔ |

| Missouri | ✔ | ✔ |

| Montana | ✔ | ✔ |

| Nebraska | ✔ | ✔ |

| Nevada* | ||

| New Hampshire | ✔ | ✔ |

| New Jersey | ✔ | ✔ |

| New Mexico | ✔ | ✔ |

| New York | ✔ | ✔ |

| North Carolina | ✔ | |

| North Dakota | ✔ | ✔ |

| Ohio* | ✔ | Deduction Allowed Under PIT (not CAT) |

| Oklahoma | ✔ | ✔ |

| Oregon | ✔ | ✔ |

| Pennsylvania | ✔ | ✔ |

| Rhode Island** | Excluded for Some Businesses | ✔ |

| South Carolina | ✔ | ✔ |

| South Dakota | No Individual or Corporate Income Tax | |

| Tennessee | ✔ | ✔ |

| Texas* | ✔ | ✔ |

| Utah | ✔ | |

| Vermont | ✔ | ✔ |

| Virginia** | ✔ | Allows Partial Deduction |

| Washington* | ✔ | |

| West Virginia | ✔ | ✔ |

| Wisconsin | ✔ | ✔ |

| Wyoming | No Individual or Corporate Income Tax | |

| District of Columbia | ✔ | ✔ |

|

Notes: *Nevada, Texas, and Washington do not levy an individual income tax or a corporate income tax but do levy a GRT. Ohio imposes an individual income tax and a GRT. Nevada treats forgiven PPP loans as a taxable gross revenue; Ohio, Texas, and Washington do not. In Ohio, Nevada, and Washington, there is no deduction for business expenses, consistent with gross receipts taxation. Under Ohio’s individual income tax, forgiven PPP loans are excluded from taxable income and the expense deduction is allowed. Under Ohio’s Commercial Activity Tax (CAT), the loans are excluded from taxable gross revenue but, consistent with gross receipts taxation, the CAT does not allow a deduction for business expenses. ** Virginia excludes forgiven PPP loans from taxable income but allows only the first $100,000 in expenses paid for using forgiven PPP loans to be deducted. California conforms to the federal tax treatment of forgiven PPP loans for some but not all businesses; the state excludes forgiven PPP loans from taxation, but the expense deduction is disallowed for publicly traded companies and businesses that did not experience a 25 percent year-over-year decline in gross receipts between 2019 and 2020. Rhode Island allows an exclusion from taxable income only for forgiven PPP loans of $250,000 or less. Sources: Tax Foundation; state tax statutes, forms, and instructions; Bloomberg BNA. |

||

Why do states have such different practices when it comes to the taxation of PPP loans? It all has to do with how states conform to the federal tax code.

All states use the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) as the starting point for their own tax code, but every state has the authority to make its own adjustments. States that use rolling conformity automatically adopt federal tax changes as they occur, which is the simplest approach and provides the most certainty to taxpayers. States that use static conformity link to the federal tax code as it stood on a certain date and must proactively adopt legislation to accept more recent changes.

It is common for states to conform to certain parts of the federal tax code but decouple from others. States that use rolling conformity sometimes adopt legislation to decouple from certain federal changes after they occur. Most states that use static conformity update their conformity dates routinely, but sometimes indecision about whether to accept new federal tax changes results in states remaining conformed to an outdated version of the IRC for many years. When static conformity states do update their conformity dates, they sometimes decouple from specific changes on an ad hoc basis. Even beyond the question of conformity dates, there has been a great deal of uncertainty surrounding the state tax treatment of forgiven PPP loans due to the way the federal government provided for the nontaxability of forgiven PPP loans.

When the CARES Act was enacted on March 27, 2020, Congress’ intent was that forgiven PPP loans be tax-free at the federal level, which is a departure from usual practice. Normally, when federal debt is forgiven for various reasons, the amount forgiven is considered taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. Taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. by the federal government and by states that follow that treatment. In normal circumstances, this is a reasonable practice. However, Congress specifically designed PPP loans as a tax-free emergency lifeline for small businesses struggling to stay open amid the pandemic, so the CARES Act excluded PPP loans from taxable income (although not by amending the IRC directly). Congress also seems to have intended that expenses paid for using PPP loans be deductible—the Joint Committee on Taxation scored the original provision as such—but did not include language to do so directly in statute. In the months following the CARES Act’s enactment, the Treasury Department ruled that expenses paid for with PPP loans were not deductible under the law as it stood at the time, citing section 265 of the IRC, which generally prohibits firms from deducting expenses associated with tax-free income. This interpretation came as a surprise to many lawmakers, since excluding the forgiven loans from taxation, but then denying the deduction, essentially cancels out the benefit Congress provided. Therefore, on December 27, 2020, when the Consolidated Appropriations Act for 2021 was signed into law, the law was amended to specify that expenses paid for using forgiven PPP loans would indeed be deductible.

As a result, most states now find they are in one of three positions. States that conform to a pre-CARES Act version of the IRC generally treat forgiven federal loans as taxable income and related business expenses (like payroll, rent, and utilities) as deductible. States that conform to a post-CARES Act but pre-Consolidated Appropriations Act version of the IRC are generally on track to exclude forgiven PPP loans from taxable income but deny the deduction for related expenses. States that use rolling conformity or that have otherwise updated their conformity statutes to a post-Consolidated Appropriations Act version of the IRC both exclude forgiven PPP loans from income and allow related expenses to be deducted. In some instances, however, states have adopted specific provisions on PPP loan income that supersedes their general conformity approach.

State policymakers are now in the position to help ensure PPP recipients receive the full emergency benefit Congress intended by refraining from taxing these federal lifelines at the state level. Denying the deduction for expenses covered by forgiven PPP loans has a tax effect very similar to treating forgiven PPP loans as taxable income: both methods of taxation increase taxable income beyond what it would have been had the business not taken out a PPP loan in the first place. In many states that currently tax forgiven PPP loans, including Arizona, Arkansas, Hawaii, Maine, Minnesota, New Hampshire, and Virginia, bills have been introduced to prevent such taxation, and Wisconsin recently acted to do the same. This situation is one in which baselines matter: from a baseline of the taxation of the forgiven loans (or the denial of the deduction), conforming to federal treatment represents a revenue loss. If, however, the baseline scenario is one in which forgiven PPP loans did not exist—the status quo ex ante—then following federal guidance is revenue neutral. This was not revenue that states counted on or expected to be able to generate.

If policymakers wish to avoid imposing taxes on these small business lifelines, however, they need to act quickly, as tax deadlines are fast approaching.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeShare this article