Key Findings

- All OECD countries with territorial taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. systems have designed provisions that seek to prevent base erosion and profit shiftingProfit shifting is when multinational companies reduce their tax burden by moving the location of their profits from high-tax countries to low-tax jurisdictions and tax havens. by multinational corporations.

- Designing a territorial tax systemTerritorial taxation is a system that excludes foreign earnings from a country’s domestic tax base. This is common throughout the world and is the opposite of worldwide taxation, where foreign earnings are included in the domestic tax base. requires balancing competing goals: exempting foreign business activity from domestic taxation, protecting the domestic corporate tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. , and creating a simple system. A system can generally only have up to two of these.

- Many countries including the United States have either reformed or adopted new rules to protect their tax bases in recent years.

- More than 130 countries are discussing a global minimum tax as an additional measure of tax base protection, although it is unclear whether this policy will amend current rules or create a complex new layer of tax rules for multinationals.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Territorial Tax Systems in the OECD

- Participation Exemptions and Dividend Deductions

- Controlled Foreign Corporation Rules

- Interest Deduction Limitations

- Country-by-Country Reporting

- Transfer Pricing Regulations

- Other Anti-Base Erosion Provisions

- Past, Present, and Future Proposals to Address Base Erosion

- Conclusion

- Appendix

Introduction

Most OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries operate what is known as a territorial corporate tax system where foreign earnings of multinational corporations are generally exempt from domestic taxation. Such systems allow for multinational businesses to make investments and generate earnings in multiple jurisdictions and remit those earnings to domestic shareholders with little or no extra taxation at the entity level. In most cases, territorial tax systems provide a full or partial exemption for foreign profits through a “participation exemption.”

The goal of a territorial tax system is to tax companies based on the location of their production, which can be difficult in today’s highly globalized and increasingly digitalized world. This is because production processes can stretch across several jurisdictions and can include transactions that are difficult to price. Companies with multinational production processes take deductions and report revenues throughout the world to allocate their profits. As such, it is often difficult to determine exactly how much profit should be taxed in each country.

The difficulty in determining the location of profits also means that territorial tax systems are vulnerable to base erosion. The fact that production processes span multiple tax jurisdictions leaves room for companies to take advantage of country-level differences in tax policy to allocate revenues and costs across tax jurisdictions in a way that can minimize their worldwide tax liability. Because territorial systems mean companies do not face an additional tax on foreign profits that are repatriated to the parent company, multinational corporations have a greater incentive to avoid domestic tax liability through various forms of tax planning.[1]

Due to these challenges, countries with territorial corporate tax systems set up rules to define if and how foreign profits are taxed, as well as rules that prevent base erosion and profit shifting. These rules include Controlled Foreign Corporation (CFC) rules, limitations on interest deductibility (thin capitalization rules), and other similar measures.

The rise of territorial tax systems and concerns about profit shifting by multinational corporations led the G20 in 2013 to propose that the OECD pursue an agenda focused on designing policies to minimize base erosion and profit shifting (the BEPS Project). Following the BEPS recommendations in 2015, many countries have adopted reforms to their territorial systems to limit some of the opportunities for tax planning by multinational corporations. In the EU, this has taken the form of the Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (ATAD).

The U.S. adopted some tenets of a territorial tax system as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in December 2017. These provisions included not only a participation exemption for dividends but also strong anti-base erosion protections with the tax on Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) and the Base Erosion Anti-Abuse Tax (BEAT).

Anti-base erosion rules and the extent to which countries exempt foreign profits from domestic taxation vary significantly from country to country. It is not clear that a “perfect” or pure territorial tax system exists. Rather, countries need to trade off among three key goals: eliminating domestic taxes on foreign profits, protecting their domestic tax bases, and making their tax rules as simple as possible.

Countries are now debating whether further measures are necessary to protect territorial tax systems from abuse. The ongoing debate over a global minimum tax is directly related to limiting opportunities for multinationals to reduce their tax liabilities through utilization of low-tax jurisdictions. Whether a global minimum tax will result in changes to existing rules meant to address the same problem (such as CFC rules) is unclear.

This paper reviews how the 37 OECD countries structure their territorial tax systems and construct base erosion rules. It reviews some of the changes incorporated by EU member states as part of the ATAD and the U.S. move to a territorial tax system in the 2017 tax reform. Finally, it summarizes the ongoing debate on a global minimum tax.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeTerritorial Tax Systems in the OECD

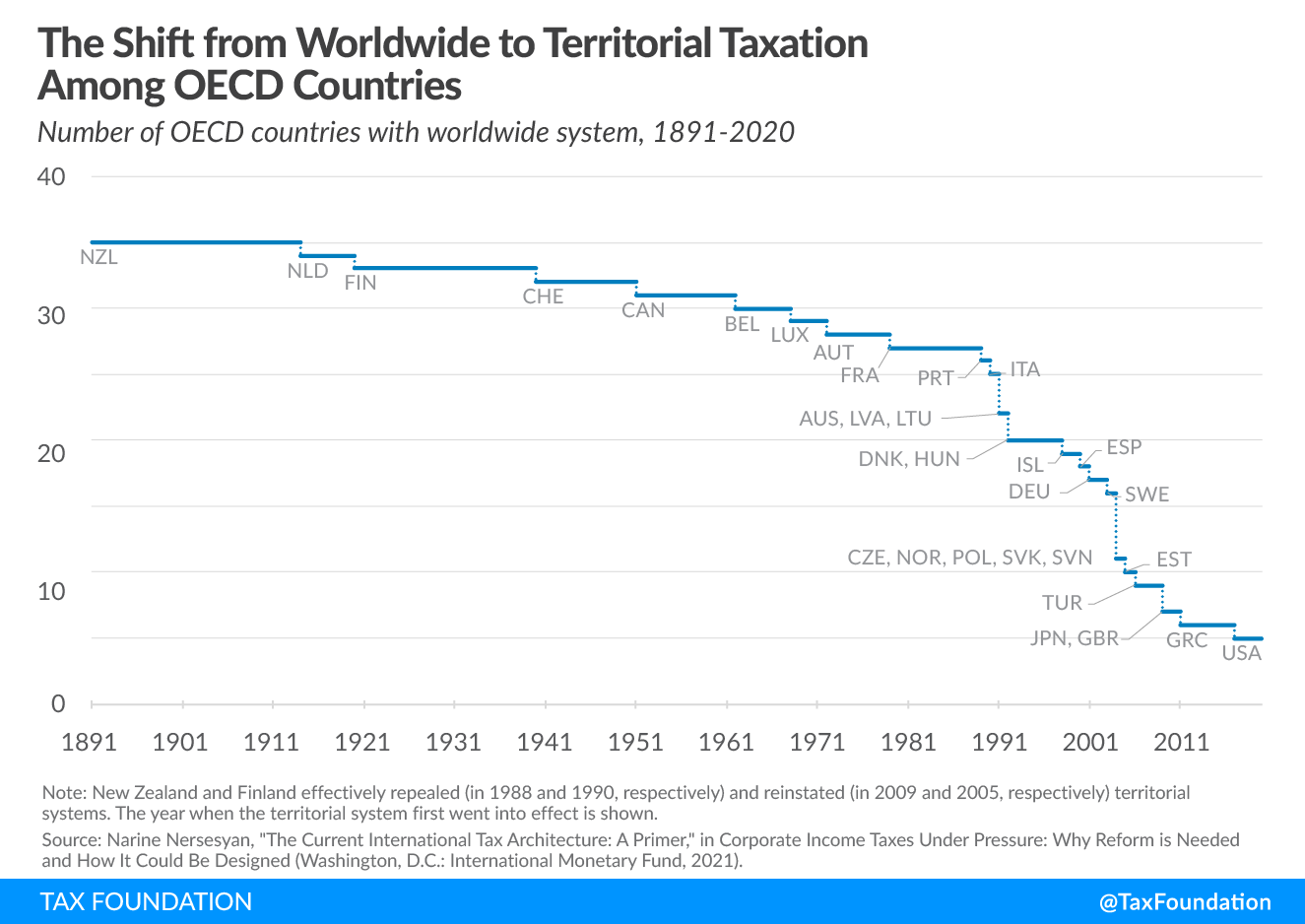

Over the last three decades, most OECD countries have shifted towards territorial tax systems and away from residence-based or “worldwide” systems.[2] The goal of many countries has been to reduce barriers to international capital flows and to increase the competitiveness of domestically headquartered multinational firms.[3]

As part of designing these territorial tax systems, countries also constructed rules that determined when and if foreign profits would be exempt from taxation. They also put in place and strengthened rules that attempt to limit profit shifting.

There are basically three major aspects that define the scope of a country’s international corporate tax system.

First are so-called “participation exemptions.” Participation exemptions are what create a territorial tax system. They allow companies to exclude or deduct foreign profits that they receive from foreign subsidiaries from domestic taxable income. This exempts those foreign profits from domestic tax, and thus they are only taxed abroad. In contrast, a worldwide system has no or few participation exemptions, and subjects most or all foreign profits to domestic taxation.

Second are controlled foreign corporation (CFC) rules. The aim of these rules is to discourage or prevent domestic multinationals from using highly mobile income (interest, dividends, royalties, etc.) and certain business arrangements to avoid tax liability on their domestic earnings. They work by defining what constitutes a “controlled” foreign company and when to attribute foreign income of these controlled companies to a domestic parent’s taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. Taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. .

Third are limitations on deductible payments. These rules are used to prevent domestic and foreign companies from using deductible payments such as interest or royalties to shift profits from high-tax into low-tax jurisdictions. While limitations on participation exemptions and CFC rules only apply to headquartered firms, these limits also address base erosion by foreign-based multinational corporations.

The United Kingdom’s shift from a worldwide tax system to a territorial system provides a good example. In 2009, the UK adopted a participation exemption that exempted foreign-earned dividends from taxation. Since then, the UK has adopted limits on deductibility of debt and additional anti-base erosion rules including a diverted profits tax (DPT) and a tax targeted at offshore intangible assets.

Other countries have gone through similar transitions in recent years by moving to territorial treatment of foreign earnings while adopting a variety of anti-base erosion rules.

A Territorial Tax System Requires Balancing Competing Goals

Looking at rules throughout the developed world, it is not clear that there exists a “perfect” or pure territorial tax system. This isn’t because a territorial tax system is a bad idea. Rather, it is because the taxation of corporate profits is fundamentally challenging. Thus, countries need to make several trade-offs in designing their systems.

A territorial tax system basically must balance three competing goals:

- exempting foreign business activity from domestic taxation,

- protecting the domestic tax base, and

- creating simple rules.

It is only possible to accomplish two of these goals at the same time. Simplification is at odds with a policy that exempts foreign business activity from domestic tax while trying to protect the domestic tax base. Protecting the domestic tax base is at odds with a policy that exempts foreign business activity alongside simple rules. Finally, a policy that protects the domestic tax base with simple rules does not fit with exempting foreign business activity from domestic taxation.

A country may opt to enact a “pure” territorial tax system that completely exempts foreign profits from domestic taxation. This would be relatively straightforward and would eliminate the incentive for multinational corporations to invert or locate in other jurisdictions. However, the lack of domestic tax on foreign profits would make profit shifting into low-tax jurisdictions much more attractive.

A country could instead enact a territorial tax system with a system of targeted anti-base erosion provisions. These provisions may reduce the incentive to shift profits and, through exemptions, maintain some competitiveness for their headquartered corporations in foreign jurisdiction. The trade-off, however, is the rules may be complex to implement.

In contrast, lawmakers could opt for a blunt solution to tax avoidance as part of their territorial tax system, such as a minimum tax on foreign profits. This may be simple and protect the tax base. However, this moves away from territoriality and would maintain an incentive for companies to invert and become a company based in a jurisdiction that does not operate a minimum tax on foreign profits.

No country in the OECD has a pure territorial tax system with no limits or restrictions. However, there are systems with fewer rules than others. Switzerland, for example, is the only OECD country that has not enacted CFC rules.

Governments around the world are incorporating supplemental measures to address the problem of base erosion and profit shifting. These additional measures add layers of complexity to the application of taxation rules. And even if it is a worthy policy goal to address base erosion and profit shifting, creating complex rules is not a good policy.

Participation Exemptions and Dividend Deductions

Countries enact territorial tax systems through what are called “participation exemptions” or dividend deductions. Participation exemptions eliminate the additional domestic tax on foreign income by allowing domestic companies to either ignore foreign income in the calculation of their taxable income or to deduct foreign income when it is paid back to the domestic parent company. Participation exemptions can also apply to capital gains. Companies that sell their shares in a CFC and realize a gain may face no domestic tax on those gains.

Some countries, such as Luxembourg, grant full exemptions for both foreign capital gains and foreign dividend income earned by domestic corporations. Other countries offer exemptions for one type of income, but not the other. Estonia, for instance, offers a full exemption for dividend income received from foreign subsidiaries (when certain requirements are met). Capital gains are only taxed when a distribution is made.

Of the 37 OECD member states, 34 countries offer some exemption or deduction for dividend income, 30 countries offer an exemption for capital gains, and 29 countries offer an exemption or deduction for both. Chile, Korea, and Mexico provide neither an exemption for capital gains nor dividends.

Participation exemptions also range from full to partial deductibility or excludability. For example, France exempts 95 percent of foreign dividend income and 88 percent of foreign capital gains. Countries providing partial exemptions often do so because it is less complex than accounting for business expenses that don’t directly correlate to physical production. Usually, companies are required to allocate overhead costs of their headquarters, such as office supplies, to foreign subsidiaries. Allocating these costs can be complex. So instead of writing rules requiring companies to allocate expenses, countries allow companies to deduct those costs domestically but tax a small portion of their foreign profits instead.

Limitations to Participation Exemptions

While most countries have enacted participation exemptions to eliminate the domestic tax on foreign profits, these exemptions are not unlimited. Countries have a range of rules that determines whether foreign profits are subject to tax when repatriated or paid back to their domestic parent.

Many European Union (EU) member states offer exemptions only when the resident company holds at least 10 percent of the subsidiary’s share capital or voting rights for some specified period. France and Germany are notable exceptions, with France requiring only a 5 percent holding, and Germany unconditionally exempting 95 percent of foreign dividends and capital gains.

In the case of the United States, the participation exemption adopted in 2017 is limited to dividends received by corporations that are 10 percent owners of foreign corporations (U.S. shareholders) according to the tax code. The foreign portion of the dividend is allowed as a deduction. However, the exemption does not apply to “hybrid dividends,” payments that are treated as tax-exempt dividends in the United States but deductible payments (such as interest) in another jurisdiction.

Some countries also limit participation exemptions and dividend deductions based on a foreign subsidiary’s location. EU member states typically limit exemptions to subsidiaries located in other EU member states or within the European Economic Area (EEA). Some countries publish a “blacklist” of jurisdictions where the tax regime is considered abusive and will not provide exemptions to profits earned in those jurisdictions. Others, such as Norway, impose a standard where a company needs to conduct real business activities abroad to qualify for a participation exemption. This directly excludes holding companies and other kinds of passive operations from receiving an exemption.

Some countries have restrictions based on the line of business a foreign subsidiary is in. For example, several countries that exempt most dividend income will not exempt profits derived from certain service-based subsidiaries such as law offices.

More detail on these rules for OECD countries can be found in Appendix Table 1.

Controlled Foreign Corporation Rules

A common concern with moving to a territorial tax system is base erosion. Under a territorial tax system, companies no longer face an additional tax on foreign profits that are repatriated to the parent company. Because of this, multinational corporations have incentives to avoid domestic tax liability by using transactions to shift income to foreign subsidiaries in jurisdictions with lower tax rates.

Countries address this issue with anti-base erosion rules called “CFC rules.” These rules aim to discourage or prevent domestic multinationals from using highly mobile income (interest, dividends, royalties, etc.) and certain business arrangements to avoid domestic tax liability. CFC rules are designed to prevent profit shifting without penalizing foreign subsidiaries engaged in legitimate business practices.

CFC rules are not unique to countries with territorial tax systems. Prior to the TCJA, the United States had rules under its worldwide tax systemA worldwide tax system for corporations, as opposed to a territorial tax system, includes foreign-earned income in the domestic tax base. As part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the United States shifted from worldwide taxation towards territorial taxation. to prevent companies from indefinitely deferring the repatriationRepatriation is the process by which multinational companies bring overseas earnings back to the home country. Prior to the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the US tax code created major disincentives for US companies to repatriate their earnings. Changes from the TCJA eliminate these disincentives. of profits that were likely being purposefully shifted out of the domestic tax base. In the United States, CFC rules were enforced by the application of “Subpart F” rules which were originally adopted in 1962.[4] With the 2017 reform an additional set of rules (GILTI) was incorporated into the U.S. tax system with the intent of eliminating some of the tax benefits of shifting income outside the U.S. tax base.[5]

CFC rules generally outline policies for taxing the undistributed income of a domestic corporation’s foreign subsidiaries. This means that if a foreign subsidiary of a domestic parent corporation is deemed a CFC and subject to a country’s CFC rules, all or a portion of its profits are immediately subject to domestic tax. The income can either be taxed separately from domestic income or incorporated into the taxable base of the domestic parent corporation.

For example, a British corporation may own a subsidiary located in the Cayman Islands. If the British CFC rules determine that the Cayman subsidiary is a CFC and the Cayman effective rate is 75 percent or less than what would be owed under British tax rules, the Cayman subsidiary’s profits then will immediately be taxed in the United Kingdom.

CFC rules are very common throughout the OECD. Only Switzerland does not have any formal CFC rules. Though some OECD countries enacted CFC rules in the 1970s, most enacted or modified their rules following the recommendations from the OECD BEPS project in 2015.[6]

Some countries often have other more qualitative base erosion provisions that attempt to accomplish the same goal as CFC rules. For example, Belgium’s CFC rules only apply to companies that are non-genuine arrangements. This requires the tax authority to determine whether the activities of a foreign subsidiary are connected to real business operations or if the entity exists simply for avoiding taxes.

Basic Structure of CFC Rules

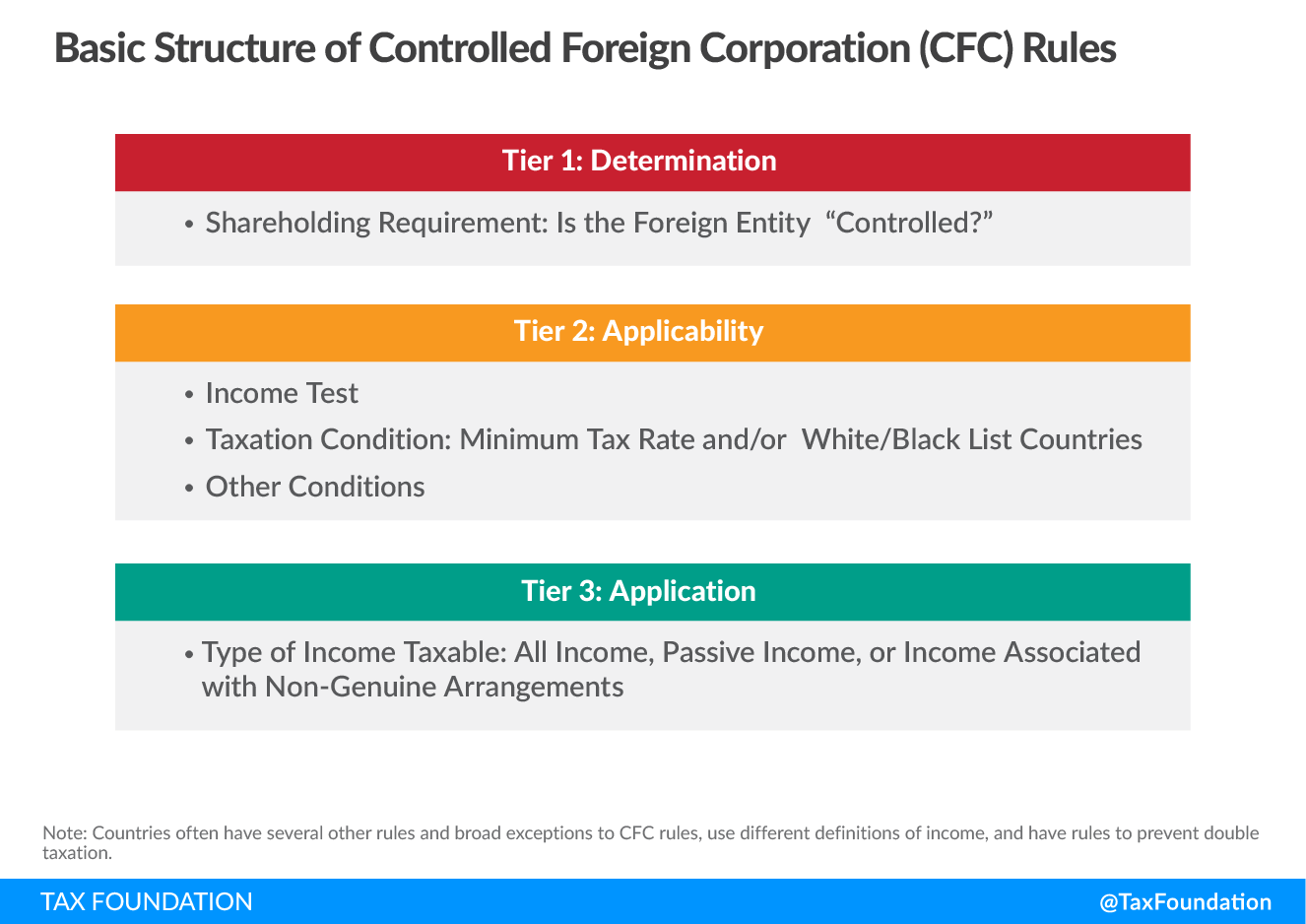

CFC rules, while complicated and highly variable, all follow a common outline. First, an ownership threshold or test is used to determine whether an entity is considered a CFC. Next, a second tier of standards is used to determine if the CFC is taxable in the parent company’s country. Finally, the rules determine what types of income are taxable.

Tier 1: Determination

The first set of rules is meant to determine whether a foreign corporation is “controlled.” The idea is that if a foreign company isn’t controlled by a domestic corporation, the domestic corporation isn’t necessarily responsible for profit shifting that may be occurring. What constitutes control varies by country and some countries have ownership thresholds that more easily trigger CFC status than others.

The most common standard is a 50 percent ownership threshold. Thirty OECD countries use this standard. This means that if one or more related corporations together own more than 50 percent of a foreign corporation’s shares, that corporation is considered a CFC.

Some countries additionally utilize a single-ownership test to determine when a shareholder of a CFC is subject to additional tax liability. A South Korean shareholder of a CFC is only taxed on CFC income if they own more than 10 percent of its share capital. Similarly, a U.S. shareholder must own 10 percent of a CFC before facing tax liability on CFC income either through Subpart F or GILTI. Of the OECD countries with CFC rules, five employ a separate single-ownership test for triggering tax liability.

Other countries, such as New Zealand and Australia, use an either-or-approach. In both countries a foreign entity is deemed “controlled” if either a single company owns more than 40 percent of the shares or five or fewer related entities own more than 50 percent of the shares. Israel has a similar rule where if a single owner owns 40 percent and together with a relative owns more than 50 percent, the foreign entity is deemed “controlled.”

Some countries use more qualitative assessments to determine CFC status. Mexico considers any foreign corporation where domestic entities have “management control” to be a CFC, and Chile considers foreign corporations to be CFCs when a domestic company has the unilateral power to alter the foreign corporation’s bylaws. New Zealand and Australia also use a qualitative control standard.

Tier 2: Applicability

While many foreign corporations might qualify as a CFC, not all will be subject to domestic taxation. There are generally two ways in which countries determine whether CFC income is taxable by domestic tax authorities.

The first way is through a “taxation condition.” This standard is aimed at preventing profit shifting to low-tax jurisdictions, or “tax havens.” The classification of tax havens is usually based on the effective corporate income tax rate levied against the CFC or a “black” or “white” list. Generally, a standard threshold is utilized to determine if the tax rate in the CFC’s country of residence encourages tax avoidance.

The threshold can either be an arbitrarily determined rate or a metric comparing the CFC’s taxation abroad to the treatment it would receive as a domestic enterprise. For instance, Mexico enforces CFC restrictions if the CFC pays an effective rate that is less than 75 percent of the rate that would be paid under Mexican tax rules. Twenty-nine countries subject CFCs to regulation based on a taxation condition.

The second way in which countries determine whether CFC income is taxable is by analyzing the type of income earned by a CFC. There are two main categories that business income can fall into: active and passive. Active income arises from traditional production activities, whereas passive income comes from legal or financial activities that do not necessarily require the participation of the person who receives the income. Passive income in most countries usually includes interest, dividends, rental income, and royalty income.[7] Countries that use income tests typically tax CFCs if most of their revenue is derived from passive income.

Eighteen countries use the percentage of total income derived from passive sources as a benchmark to determine whether CFC rules apply to an entity. The benchmarks diverge enormously. New Zealand applies CFC rules if passive income is greater than 5 percent of total CFC income, whereas Hungary applies CFC rules if passive income is greater than 50 percent of total CFC income.

A few countries also have further conditions they use to determine what income from a CFC is taxable. The United Kingdom has several tests it uses, including length of share ownership and the foreign company’s profit margin. Colombia deems 100 percent of earnings as passive if passive earnings exceed 80 percent of CFC earnings. However, if more than 80 percent of earnings are active, then 100 percent of earnings are deemed active.

Tier 3: Application

Once a country’s CFC rules determine that a company’s CFC’s income is taxable domestically, the rules then define what income is subject to tax. These rules also vary significantly and can apply to a share of passive income or both active and passive income. Of the countries with CFC rules, 15 only tax passive income earned by CFCs while 13 impose taxes on both active and passive income of CFCs. The rest of OECD countries with CFC rules either generally tax CFC income in proportion to passive income (while in some cases capturing some active income) or tax all income of CFCs that are clearly used for the purpose of limiting tax liability (non-genuine arrangements).

Additional Rules and Exemptions

In addition to these general rules, nearly every country has exemptions that determine when a CFC may not be subject to these rules or taxation at all. For example, the EU Constitution[8] contains freedom principles to facilitate business operations between member states (including the case of freedom of movement and freedom of establishment). The European Court of Justice has ruled that CFC rules should only target wholly artificial arrangements within the EU to avoid infringing upon these freedoms.[9] With the EU Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (ATAD), EU countries have designed rules that exempt CFC income from taxation when they operate in other EU and European Economic Area (EEA) countries and the CFCs are engaged in real economic activities. In addition to the real economic activities rule, some EU members also require a signed tax treaty with the other EU member country for the CFC exemption to apply.

Countries such as Japan and Korea have similar active business exemptions. Other countries, such as Chile, Finland, and Sweden, exempt CFCs if they operate in “whitelist,” or treaty countries. Some countries may exempt CFCs if their profits are below a de minimis threshold. The Netherlands has a minimum substance safe harbor: if a company has annual labor costs of more than €100,000 and an office space for 24 months, the CFC profits are exempt from taxation.

Besides exemptions, countries also have provisions that seek to prevent the double taxation of income that has already been taxed through a CFC rule when that income is repatriated to its parent company.

Appendix Table 2 has more details on the structure of CFC rules.

Interest Deduction Limitations

Under most tax systems throughout the world, the interest corporations pay on loans and bonds is deductible against taxable income, while interest income is taxable. It is common practice for a multinational corporation to lend itself money, by providing loans to and from subsidiaries located in foreign countries. These cross-border loans are helpful for companies to expand and make new investments in foreign markets.

However, as with other deductible expenses, interest deductions can be used to exploit cross-country differences in corporate tax systems to reduce corporate tax liabilities. Multinational corporations have an incentive to take out loans in high-tax countries, where they can take deductions, and lend from low-tax countries, where they can realize interest income, resulting in a lower worldwide tax burden.

Interest deduction rules can be seen as supplemental to CFC rules. CFC rules apply only to resident corporations whereas interest deduction limitations apply to all corporations—foreign and domestic.

To combat potential abuse of interest deductions, countries place limitations on these expenses. Thirty-five of the 37 OECD nations place some sort of formal limitation on interest expense deductions. Ireland currently has informal limitations on interest deductions but is set to implement formal rules starting January 1, 2022. The only country that does not have any widely applicable limitation on interest deductions is Israel. Most of the EU members modified their regimes and included an interest expense limitation rule due to the application of ATAD. In the United States, the rules governing interest deduction limitations were tightened by the TCJA with a new business interest limitation rule that resembles the OECD parameters established in BEPS Action 4.

Interest deduction limitations are often implemented through rules specifically targeted at multinational corporations, called thin capitalization rules.[10] Thin capitalization rules target companies whose debt levels far exceed equity. Most of these rules are designed to apply when a company has a debt-to-equity ratio beyond a predetermined threshold. Of the 35 OECD nations which currently operate interest deduction limitation rules, 16 employ this method. In some cases, tax authorities also use the debt-to-equity ratio on assessments to evaluate whether interest deductions can be restricted.

In recent years, countries have introduced much broader interest deduction limitations. These limits are sometimes called “earnings stripping” rules and restrict interest deductions to a set percent of income. The standard was set up by the OECD in the BEPS project and made mandatory by the application of ATAD to all EU members. The general standard was to limit interest deductions beyond 30 percent of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) with a €3 million de minimis threshold for deductible interest expenses.

Twenty-eight countries have rules generally based on that OECD approach. The United States is one of these countries and adopted a similar rule as part of the TCJA in 2017. Beginning in 2022, however, interest deductions for U.S. companies will be limited to 30 percent of EBIT rather than EBITDA. This represents an even broader limitation on interest deductibility.

A few countries with debt-to-equity-style thin capitalization rules also pair them with earnings stripping rules. Eight OECD countries with thin capitalization requirements also use an earnings stripping rule, with Belgium employing this restriction in conjunction with a debt-to-equity ratio.

Few OECD members have restrictions on interest deductibility that employ more qualitative assessments. Generally, these assessments examine the intent and fairness of intracompany loans. Specifically, the loan must be made for a clear commercial purpose and must have interest obligations like those that would be offered by a third party. Sweden, for example, denies deductions if the interest on the loan is taxed at less than 10 percent, if the loan does not serve a commercial purpose, and if the loan would not have been made by an independent third party. Most of the rules limiting interest deductions in the EU have recently changed since the EU member states have implemented the ATAD, which establishes a standard for interest deductions rules. Ireland is scheduled to implement its new interest deduction limitations in January 2022.

See Appendix Table 3 for more information on interest deduction limitations for OECD countries.

Country-by-Country Reporting

In some cases, evidence of base erosion and profit shifting can be identified through transparency measures. To facilitate the necessary transparency the OECD’s BEPS Action Plan outlined minimum reporting rules to be promulgated by member states.

These rules require that companies with total revenue of €750 million (or the local currency equivalent) provide an annual “Country-by-Country Report.” These reports include the revenue, pretax income, and income tax paid and accrued in every country in which they do business, as well as their number of employees, stated capital, retained earnings, and tangible assets in each. Additionally, the companies must identify the specific subsidiaries operating in a particular tax jurisdiction, and the business activities in which they engage.

These reports can be subject to misinterpretation and are best seen as a general view of where a company operates and earns profits rather than clear evidence of profit shifting.[11]

Thirty-six of the 37 OECD countries have adopted the Country-by-Country Reporting requirements, while Israel is in the process of doing so.

Transfer Pricing Regulations

Another common strategy in tax planning that can lead to base erosion is abuse of transfer pricing rules. Transfer pricing abuse occurs when a multinational enterprise sells itself goods and services, at an inflated price, from a subsidiary in a low-tax jurisdiction to the parent or another subsidiary in a high-tax jurisdiction. The taxable profits in the high-tax jurisdiction are reduced by these inflated costs, and a portion of those profits is shifted to the low-tax jurisdiction. To prevent this, countries almost uniformly demand that transactions between related parties are conducted at arm’s length, or “priced as if the enterprises were independent…and engaging in comparable transactions under similar conditions and economic circumstances.”[12]

While countries have broad authority to impute tax liability for transactions deemed to be in violation of the arm’s length principle, documentation requirements on the transacting firms can be helpful to tax authorities in identifying potential profit shifting risks and act as a deterrent for multinationals to engage in profit shifting.

The additional transfer pricing rules require companies to justify more consistently and clearly how they determined the price at which they would be providing themselves a product or service in a cross-border transaction. These regulations can partially reverse the activities that businesses previously undertook to minimize their tax burden through transfer pricing. These rules have been implemented in various forms including master and local file documentation of transfer pricing practices. Seventeen OECD countries had requirements for filing both master and local documentation as of 2017.[13]

Other Anti-Base Erosion Provisions

Several countries have additional rules to prevent base erosion. Many of these policies have been adopted relatively recently, and some of these new provisions were developed as part of the OECD’s BEPS project.

Countries including Australia, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States have introduced unique anti-base erosion provisions. See Appendix Table 5 for other information about these rules.

Australia: Multinational Anti-Avoidance Law and Diverted Profits Tax

Australia has an additional anti-base erosion provision, titled the Multinational Anti-Avoidance Law (MAAL), which allows the Australian Taxation Office to impose penalties of up to 120 percent of the amount of avoided tax under certain circumstances. The MAAL has been in effect since 2016 and applies to significant global entities (SGEs), which are defined as multinational businesses with global revenues of $1 billion AUD or more or an entity which is part of a multinational group with at least $1 billion AUD in global revenue. The MAAL penalty applies to business structures or transaction arrangements for which one of the main purposes of the structure is to gain Australian tax benefits or both an Australian and foreign tax benefit.

Australia has had a diverted profits tax (DPT) in force since 2017. Like the MAAL, the Australian DPT also applies to SGEs. The DPT applies a penalty rate of 40 percent on profits that are deemed to have been diverted from the Australian corporate tax base through arrangements that do not reflect economic substance. A cross-border transaction where the tax paid is less than 24 percent is possibly at risk of the DPT. The Australian DPT is designed to be a harsh penalty for business practices that result in corporate taxes being paid at a rate lower than what the tax authority would deem appropriate or avoiding taxes altogether.

Germany: Royalty Barrier Rule

In 2017, Germany introduced a royalty barrier rule that impacts royalties paid on intra-group transactions that are subject to an effective tax rate below 25 percent. The rule denies the deductibility of those payments. However, the royalty barrier does not apply when the recipient of a royalty is covered by Germany’s CFC rules.

The royalty barrier rule was designed to apply to royalty payments for the use of intellectual property that is in a jurisdiction that provides a tax preference that is deemed to be harmful. A “harmful” tax preference is one that does not follow the BEPS standards for modified nexus.[14] The German Ministry of Finance publishes a list of such policies roughly in line with the OECD’s own list of harmful preferential regimes.

In some cases, a regime is still being reviewed for “harmful” status. This is the case of the U.S. policy on Foreign Derived Intangible Income which provides a lower tax rate for profits from exports that are connected to intellectual property held within the United States.

United Kingdom: Diverted Profits Tax and IP Tax

As mentioned previously, the UK introduced a Diverted Profits Tax (DPT) in 2015. The policy is commonly referred to as the “Google Tax,” and is intended to target tax avoidance practices of large multinationals. This policy sits on top of all the other anti-base erosion rules in the UK and is meant to target specific transactions that tax authorities deemed to be abusive. The application of the tax in the United Kingdom, specifically, is complex and somewhat subjective in nature.[15] The DPT applies a 25 percent tax rate on taxable profits that are artificially diverted away from the UK tax base.

More recently, in 2018 the UK introduced a separate tax targeted at intellectual property (IP) located in low-tax jurisdictions. This policy applies to any foreign company with more than ₤10 million in sales derived from IP in countries with corporate tax rates below 50 percent of the UK rate. Businesses subject to the policy need to pay UK corporate tax on their IP income. Offshore income could be exempt from the tax if there is sufficient business substance in the offshore location or if the UK has a double tax treaty with the jurisdiction that includes a nondiscrimination provision.[16]

United States: GILTI, FDII, and BEAT

With the adoption of the TCJA in 2017, the U.S. moved to a partially territorial tax system by providing both a participation exemption for dividends from foreign sources and anti-avoidance rules. In doing so, the U.S. took a unique approach with three new rules: a tax on Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI), Foreign Derived Intangible Income (FDII), and the Base Erosion and Anti-abuse Tax (BEAT).[17]

GILTI is a new category of foreign income that includes half of foreign earnings exceeding a 10 percent return on a company’s foreign tangible assets. It is subject to a tax rate between 10.5 and 13.125 percent on an annual basis. Foreign tax credits applicable to GILTI are limited to 80 percent and excess credits cannot be carried forward. The tax operates on the same platform as Subpart F income, but it is levied at the shareholder level.

A high-tax exemption rule that was put in place for Subpart F also applies to GILTI. Foreign profits that are taxed at a rate that is at least 90 percent of the U.S. rate (or 18.9 percent), can be excluded.

While GILTI taxes half of active and passive foreign earnings above a 10 percent return to tangible assets, Subpart F is targeted at passive earnings. Subpart F income is taxed at the full corporate rate of 21 percent, however.

In practice, GILTI may be subject to U.S. taxation even when foreign profits are subject to a foreign tax rate over 13.125 percent. This is because prior law limits on foreign tax credits apply to GILTI’s foreign tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. .[18]

GILTI was paired with FDII which provides a reduced tax rate for earnings from exports based on intangible assets held within the U.S. FDII was meant to face a similar tax rate as GILTI (13.125 percent) to balance incentives between locating intangible assets offshore or holding them in the U.S.[19]

The BEAT is a tax created to combat earning stripping out of the United States. The tax is applied at a rate of 10 percent of modified taxable income minus the regular corporate tax liability (not below zero).[20] It targets multinational corporations with gross receipts of at least $500 million in the previous three taxable years, with base erosion payments to related foreign corporations that exceed 3 percent (2 percent for certain financial firms) of the total deductions taken during the fiscal year.

Past, Present, and Future Proposals to Address Base Erosion

Following the 2015 reports from the BEPS project, many countries moved to change their rules in line with the recommendations from the OECD. Two important examples of this include the implementation of ATAD by EU countries and the adoption of the TCJA in the United States.

Following the adoption of the TCJA in 2017, countries have begun exploring more comprehensive rules changes. The Biden administration has proposed an expansion of GILTI and added its voice to the call for a global minimum tax.

On July 1, 2021, 130 countries and jurisdictions endorsed an outline for new rules that would change where multinationals owe taxes and establish a global minimum tax of at least 15 percent.[21]

The BEPS Project Recommendations

The original BEPS project concluded in 2015 with reports covering 15 different action items.[22] It provided minimum standards for harmful tax practices, rules to prevent treaty abuse, requirements for country-by-country reports for companies, and procedures for tax disputes. Additionally, it outlined recommendations on definitions of permanent establishments, policies to prevent hybrid mismatch arrangements, CFC rules, and interest deduction limitations.

Each of these rules was meant to close gaps in cross-border tax rules that had contributed to the problems of profit shifting.

Following these reports and recommendations, the Inclusive Framework on BEPS was established as a forum for countries beyond the OECD members to participate in implementing BEPS policies. In 2016, this group included 82 countries, but it has grown to 139 countries and jurisdictions.[23]

Inclusive Framework members have committed to implement the comprehensive changes recommended in the BEPS reports, although not all on the same timeline.

The Inclusive Framework is led by a Steering Group that includes representatives from 24 countries.[24]

The European Union: Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive

In January of 2016, the European Union (specifically, the EU Council) presented a proposal to incorporate some base erosion measures into the EU member states’ tax systems to level the playing field among them.[25] The package lays down rules against tax avoidance that directly affect the functioning of the EU market.

The measures to reduce the risk of base erosion and profit shifting contained in the ATAD include:

- Exit taxation rules

- CFC rules

- Hybrid mismatch rules

- General anti-avoidance rules

- Interest deductibility rules

As of today, most EU countries have finished implementing these rules.

Exit Taxation

Exit taxes are aimed at preventing tax avoidance by the transfer of assets, or other strategies, to move a business from one country to another in search of more favorable tax treatment. For instance, a business may want to move an intellectual property asset from the parent company in the EU to a jurisdiction outside the EU. The business may be seeking better tax treatment for the profits from that asset. The exit tax rules would require the company to pay capital gains tax to its home jurisdiction in the EU prior to transferring that asset to the foreign jurisdiction. This is a “deemed” capital gain rather than a realized gain since the asset is staying within the same company and is just being relocated to a subsidiary in a different jurisdiction.

CFC Rules

The ATAD provided two models of CFC rules that EU countries could use as a basis for reforming or adopting their own CFC rules. Model A focuses on applying CFC rules to passive income while Model B focuses on taxing income arising from non-genuine arrangements that were specifically designed to gain a tax advantage. Fourteen EU countries have followed Model A in their implementation while nine have followed Model B.[26] Bulgaria, Finland, and France are not following either model while the Netherlands has a combined approach of the two models. See Appendix Table 4 for which countries have adopted the different models.

There are optional exceptions to both Model A and Model B.

There are two Model A optional exceptions. First is whether to apply a “substantive economic activities” test for CFCs based in non-European Economic Area countries. The second is whether to use a threshold of one-third of earnings from passive sources as a determining factor in applying CFC tax treatment.

An option under Model B allows countries to exclude some income from a CFC if its accounting profits are less than €750,000 and non-trading (passive) income is less than €75,000 or less than 10 percent of its operating costs.[27]

Hybrid Mismatch Rules

Hybrid mismatches occur when a payment is deductible for an entity in one country and the income from that payment is exempt for an entity in another country. This happens because different countries often have different rules defining deductions or exempt income. Hybrid mismatch rules are aimed to prevent corporations from obtaining benefits from different legal and tax treatment of transactions through the laws of different jurisdictions. The ATAD implementation timeline for hybrid mismatch rules has set January 1, 2022 as the deadline for the rules to be in action. As of August 2020, Romania was the only EU member state that had gained approval from the European Commission for meeting intermediate deadlines on adopting hybrid mismatch rules.[28]

General Anti-avoidance Rules

The General Anti-Avoidance Rule (GAAR) is meant to provide tax authorities with the opportunity to analyze the primary purpose of business arrangements. If, for example, a business arrangement is determined to have the primary purpose of saving money on taxes, the business arrangement can be disregarded for tax purposes. This may mean that an offshore structure is treated as fully taxable in the headquarters’ country.

Interest Deductibility Rules

ATAD provided a template with options for implementing interest deductibility rules. In general, “excess borrowing costs” are deductible up to 30 percent of EBITDA.

However, countries can opt to use a group escape clause based on an equity to total assets ratio. Countries could also choose a “group EBITDA” test where deductions for excess borrowing costs for a corporate group (defined for financial accounting purposes) are limited to 30 percent of EBITDA. Eleven EU member countries use the group escape clause while 15 use the group approach for limiting interest deductions (it is not yet clear which approach Ireland will take).

Countries can also choose to provide a de minimis threshold where borrowing costs are deductible up to €3 million. Twenty-three EU member states have adopted this de minimis threshold.[29] See Appendix Table 4 for which countries have adopted the de minimis threshold or a group escape clause.

Proposals in the United States

Since the adoption of the TCJA, U.S. policymakers have proposed going further with additional changes to tax rules for multinationals.

President Biden has proposed several changes to GILTI and proposed a replacement policy for BEAT.[30]

The Administration has proposed expanding the GILTI tax base by removing the exemption for a 10 percent deemed return on tangible assets. In addition, the Administration’s proposal would increase the GILTI inclusion from 50 percent to 75 percent. Combined with the Administration’s proposal to raise the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate to 28 percent, the effective tax rate on GILTI would range from 21 percent to 26.25 percent (assuming the 80 percent rule for foreign tax credits remains in place).

These changes to GILTI would make the participation exemption which was adopted in the TCJA essentially meaningless for most U.S. multinational companies.

The tax base for GILTI would also be expanded to include more income from extractive industries and deductions for domestic expenditures would be limited in some cases.[31]

Biden has also proposed a structural change to GILTI. Rather than calculating GILTI on overall foreign income, the proposal would have companies calculate GILTI on a country-by-country basis. This would limit the ability of companies to blend higher taxed income to offset lower taxed income, but it would also create new distortions. Without the ability to carry forward excess tax credits or losses, companies could see GILTI liability that is artificially high relative to their foreign net income over time. Biden has also proposed repealing BEAT and replacing it with a new policy called Stopping Harmful Inversions and Ending Low-Tax Developments (SHIELD). SHIELD would deny deductions for U.S. entities whose parent company is based in a jurisdiction that levies a low rate of tax. The specific tax rate would be tied to the 21 percent basic GILTI rate until a global minimum effective tax rate is implemented.

Global Minimum Tax Proposal

On July 1, 2021, 130 of the 139 members of the Inclusive Framework on BEPS endorsed an outline that would change where large multinational companies owe taxes and included a global minimum tax.[32]

This agreement generally follows the work published by the OECD in October 2020 prior to the Biden administration’s entrance to the discussion. That blueprint includes two main rules for the global minimum tax which are also referenced in the July 1 statement.[33]

First, an income inclusion rule (IIR) would, like GILTI and CFC rules, tax foreign earnings of companies under certain conditions. Second, an under-taxed payments rule (UTPR) would deny cross-border deductible payments in some instances. Both rules would be triggered by a minimum effective tax rate which would require countries to agree on a rate and a base for the minimum tax. These rules are typically referred to as OECD’s “Pillar 2.”

The statement from July 1 not only identifies a tax rate but also has a general description of a tax base. Like GILTI, a deduction for a return on tangible assets would be provided. Initially this would be 7.5 percent, though it would fall to 5 percent after five years. A separate deduction for payroll costs would also apply at 7.5 percent initially and then 5 percent after five years.

There are several differences between the Biden proposal and the OECD framework. These differences include the carveouts for tangible assets and payroll as well as the treatment of losses and foreign tax credits. Unlike GILTI, Pillar 2 is only intended to apply to companies with revenues above a €750 million threshold.

The 130 countries of the Inclusive Framework that endorsed the statement on July 1 also agreed to continue work on rules that require companies to pay more taxes in countries where they have customers. Specifically, they said that large companies with high profit margins should have 20-30 percent of profits over a 10 percent profit margin allocated based on the location of customers.

It is expected that a final report with the specifics of the global minimum tax will be released by the end of 2021 along with an implementation timeline which itself could take several years.

A global minimum tax could be an extension of the existing anti-base erosion rules including CFC rules and interest deduction limitations, but it could also be somewhat duplicative. It is unclear at this point whether the final proposal would sit on top of existing anti-avoidance rules or if current cross-border tax rules would be amended in line with the global minimum tax. It is also possible that countries will want to adopt their own unique versions of the policy.

For the U.S., the Biden administration’s proposals strike a different course than the OECD blueprint on the minimum tax. It is unclear whether those differences will remain or if the U.S. rules for cross-border taxation will be made to align with an OECD agreement.[34]

Conclusion

Most countries generally exempt foreign profits from domestic taxation through a “territorial” tax system. A territorial tax system requires balancing several competing goals and requires countries to make certain trade-offs. One challenge is that a territorial tax system is susceptible to base erosion or profit shifting.

Over the last decade, countries have worked to address base erosion and profit shifting. OECD countries have made a variety of decisions as they have worked to balance issues of exempting foreign business activity from taxation and protecting domestic tax bases. Many related policies are still developing and there is some uncertainty as to how things will evolve in the coming years.

Even following significant reforms and adoptions of new anti-avoidance rules, countries are still looking for new ways to address various forms of profit shifting. One challenge that countries face in developing a global minimum tax is how the new rules might fit with or complicate those already in place.

From a policy perspective it is appropriate to combat base erosion and profit shifting, but policymakers need to keep in mind the need for simplicity to avoid increasing the compliance burden on taxpayers and administrative burdens on tax authorities.

Appendix

| Participation Exemptions for Dividends | Participation Exemptions for Capital Gains | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Deduction or Exemption | Applicable criteria | Deduction or Exemption | Applicable criteria |

| Australia | 100% | Dividends from foreign subsidiaries of which Australian companies hold at least 10% are considered “Nonassessable, Nonexempt” (NANE) income, which is excluded from taxable income. | 100% | Capital gains and losses on the disposal of shares, proportionate to the degree to which the company’s assets are used in active business. In both cases Australian entity or individual must hold 10% interest or participation. |

| Austria | 100% | Dividends received by a nonresident company if the company is similar to an Austrian company. Parent holds 10% equity or capital. The 10% is held for a year continuously. From January 2019 the exemption method changed to a credit method. | 100% | Capital gains on the sale of qualifying participations are tax-exempt. From January 2019 the exemption method changed to a credit method. (incorporation of CFC rules). |

| Belgium | 100% | €2.5 million acquisition value requirement. 10% holding. The distributor must be subject to CIT on the profits. Full ownership for a period of at least 1 year. | 100% | €2.5 million acquisition value requirement. 10% holding. The distributor must be subject to CIT on the profits. Full ownership for a period of at least 1 year. |

| Canada | 100% | Dividends received by corporate shareholders out of the “exempt surplus” of foreign affiliates are not taxable; “exempt surplus” generally relates to active business income in a country with which Canada has an income tax treaty. | 50% | Applies to all capital gains, regardless of tax residency of affiliates. |

| Chile | No | N/A | No | Chile had a special regime that excluded dividends from withholdings on publicly traded stock corporations. The regime was repealed, and it will phase out in 2022. |

| Colombia | 100% | Applies to domestic holding companies. | No | None. |

| Czech Republic | 100% | Dividends are exempt when transactions are made between EU or EEA residents and the holding is more than 10% for an uninterrupted period of 12 months. Dividends are exempt for sales of shares in non-EU/EEA resident subsidiaries when that subsidiary is a tax resident in a country that has concluded a tax treaty with Czech Republic, has a specific legal form, meets the requirements for the dividend exemption under the EU parent-subsidiary directive, and is subject to a home country tax of at least 12%. | 100% | Capital gains are exempt when transactions are made between EU or EEA residents and the holding is more than 10% for an uninterrupted period of 12 months. Capital gains are exempt for sales of shares in non-EU/EEA resident subsidiaries when that subsidiary is a tax resident in a country that has concluded a tax treaty with Czech Republic, has a specific legal form, meets the requirements for the dividend exemption under the EU parent-subsidiary directive, and is subject to a home country tax of at least 12%. |

| Denmark | 100% | Dividends and capital gains received by a Danish company on subsidiary shares and group shares are generally exempt. | 100% | Dividends and capital gains received by a Danish company on subsidiary shares and group shares are generally exempt. |

| Estonia | 100% | CIT is not charged again in a distribution of dividends if there is a 10% holding for EEA members, or Switzerland. For non-EEA countries a 10% holding is required, and income tax was paid or withheld in the foreign jurisdiction. | 100% | CIT is not charged on capital gains unless there is a distribution. For non-EEA countries a 10% holding is required, and income tax was paid or withheld in the foreign jurisdiction. |

| Finland | 100% | Dividends received from companies in the EEA or EU members are exempt. | 100% | Capital gains from the sale of shares are exempt when earned from sales of fixed assets that are deemed to be part of the seller’s business income generating assets if: seller owns at least 10% of capital; shares held at least for 1 year; shares are not of a real estate or LLC. |

| France | 95% | 95% net dividend exclusion. French parent holding 5% of subsidiary. 2-year holding period. 99% exemption on dividends in consolidated groups. | 88% | French parent holding 5% of subsidiary. 2-year holding period. 88% of capital gains exempted if gains arise from the sale of shares that form part of a substantial investment, and the shares have been held for at least 24 months. |

| Germany | 95% | Not applicable if dividends are tax-deductible for the payer. | 95% | 95% of capital gains from the sale of shares exempt if taxpayer held a 1% direct or indirect interest within the last 5 years. |

| Greece | 100% | Exemption applies for dividends received from domestic or EU subsidiaries if 10% of shares held for a minimum of 24 months in hands of the parent company. | 100% | Exemption applies for capital gains from domestic or EU subsidiaries if 10% of shares held for a minimum of 24 months in hands of the parent company. |

| Hungary | 100% | Applies to dividends without any holding requirements. | 100% | Applies to capital gains derived from the sale of an investment, if the taxpayer holds a subsidiary (a non-CFC) for at least one year and the acquisition must be reported to the Hungarian authorities. Similar rules apply for capital gains derived from the sale of qualifying intellectual property. |

| Iceland | 100% | Dividends paid to a company within the EEA are not taxed if a tax return from the company is submitted. | 100% | Tax withheld will be reimbursed in the year following the year of the payment. Capital gains from a sale of shares of a company are exempt. |

| Ireland | 0% | Dividend exemption for Irish dividends and other EEA company dividends with specific requirements. Tax credit for withholding and underlying corporate tax is available for foreign-sourced dividends. | 100% | Exempts capital gains between treaty countries (5% holding requirement). Investee must be a trading company or a member of a trading group. Interest held for a continuous 12-month period, ending with 2 years from the date of the disposal. |

| Israel | 100% | Only for an Israeli holding company, investing abroad. Dividend exemption for dividends from a qualifying subsidiary. | 100% | Only for an Israeli holding company, investing abroad. Capital gains from the sale of shares of the subsidiary are exempt. |

| Italy | 95% | Domestic and foreign dividends are 95% exempt from CIT. No minimum requirements for the exemption. | 95% | Capital gains are 95% exempt if they: have been held for 12 or 13 months continuously; are classified as financial fixed assets; are not located in low-tax jurisdiction; and the company carries on business activities. |

| Japan | 95% | To qualify for the exemption, the taxpayer’s ownership stake in the foreign firm must be at least 33.3% with a holding period of more than 6 months. | 0% | No exemption applies. |

| Korea | 0% | No exemption applies. | 0% | No exemption applies. |

| Latvia | 100% | Redistributed dividends are exempt when: the payer pays corporate tax in its country of residence, and the dividends have been subject to withholding at the distributing jurisdiction; the payer is not from a “blacklist” country; dividends are not treated as a tax-deductible expense in the payer’s residence. | 100% | Applies to holding companies that have held shares for at least 36 months. Does not apply to gains from sale of shares where more than 50% of assets are Latvian real estate or from sale of shares of companies in low-tax jurisdictions. |

| Lithuania | 100% | Dividends are exempt from CIT if the company holds at least 10% of the shares of the subsidiary for at least 12 months. | 100% | Capital gains derived by a Lithuanian resident holding company or PE, if the company is in Lithuania or in an EU/EEA member or the country has a treaty with Lithuania. The company must hold 10% of the voting rights for at least 2 years. In the case of a reorganization the period is 3 years. |

| Luxembourg | 100% | See applicable criteria for participation exemption for capital gains. | 100% | Dividends and capital gains exempted if: held for uninterrupted period of 12 months; at least 10% or not below acquisition price of €1.2 million (€6 million for capital gains). |

| Mexico | No | N/A | No | N/A |

| Netherlands | 100% | See applicable criteria for participation exemption for capital gains. | 100% | Dividends and capital gains derived from 5% shareholder: subsidiary is not a mere portfolio investment; reasonable effective tax rate (subject to tax test); less than 50% of the assets are passive (asset test). If the exemption is not applicable credit is available. |

| New Zealand | 100% | None. | 100% | None. |

| Norway | 97% | Dividends received by a Norwegian resident limited company from another company in the EEA are 97% exempt. If it is nonresident in the EEA, then there is a 10% holding requirement for at least 2 years. Intragroup dividends are 100% exempt. | 100% | Capital gains derived from the disposal of shares by a Norwegian Limited company or EEA resident are exempt. In low-tax jurisdictions the exemption applies when the company held has business activities. For shares in non-EEA countries there is a 10%- and 2-years holding requirement. The sold company cannot be in a low-tax jurisdiction. |

| Poland | 100% | Dividends received by a Polish resident company from other Polish companies or EU/EEA, or Swiss companies are exempt. To qualify for the exemption there must be economic reality to the transaction. | No | N/A |

| Portugal | 100% | See applicable criteria for participation exemption for capital gains. | 100% | Dividends received and capital gains realized by a resident company from a domestic or foreign shareholding are exempt, provided that the shareholder is not considered a transparent entity and has held directly or indirectly 10% of the capital or voting rights of other company for at least 12 months. The subsidiary may not be resident in a listed tax haven and must be subject to an income tax that is equal to at least 60% of the Portuguese corporate tax rate. |

| Slovak Republic | 100% | Dividends are exempt to the extent they have not been deducted by the payer of the dividends and Slovakia has a treaty or an agreement for the exchange of information with the other country. | 100% | Capital gains from the sale of shares and ownership interests are exempt from tax if: income arises no earlier than 24 months after the acquisition date of at least a 10% direct interest in the registered capital. the taxable person carries out significant functions in Slovakia and has the personnel and equipment to carry the functions. |

| Slovenia | 95% | 95% dividend exemption on dividends received from another Slovene company, an EU subsidiary, or from any other country that is not “blacklisted” in Slovenia. | 47.50% | Capital gains exemption applies if at least 8% of shares have been held for more than six months.

Capital gains subject to the EU merger directive are exempt. |

| Spain | 95% (prior to January 1, 2021 a 100% exemption applied). | See applicable criteria for participation exemption for capital gains. | 95% (prior to January 1, 2021 a 100% exemption applied). | Dividends and capital gains from shareholdings in Spanish and foreign subsidiaries may be exempt if 5% is held in the subsidiary for a one-year period. |

| Sweden | 100% | See applicable criteria for participation exemption for capital gains. | 100% | Dividends and capital gains derived from another resident company are exempted if the shares qualify as business related. Shares must be held for at least one year. The same exemption applies in specific cases for nonresident companies; features need to be like Swedish LLC or economic associations. Shares in an EU resident company can qualify as tax-exempt if the holding represents at least 10% of the capital. |

| Switzerland | 100% | Dividends received from a qualifying participation in a resident or nonresident company. A participation is considered qualifying if the recipient company owns at least 10% of the capital of the payer company or the value of the participation is at least CHF 1 million. | 100% | There is a participation relief for capital gains if 10% of shares in a company have been held for more than one year. |

| Turkey | 100% | See applicable criteria for participation exemption for capital gains. | 100% | In the case of foreign companies, nonresident payor is a foreign company or an LLC; the taxpayer owns 10% of the paid in capital in the last year; foreign profits are subject to at least 15% foreign income tax; dividends remitted to Turkey by the date that the corporate tax return is due; capital gains derived from the sale of foreign participations held at least for two years are exempt from corporate income tax. |

| United Kingdom | 100% | Exemption applies to dividends except for dividends received by banks, insurance companies, and other financial traders. | 100% | Capital gains are exempt when the selling company continuously owned at least 10% of the shares of the company sold for at least 12 months in the 6 years before the disposal. |

| United States | 100% | Parent holds 10% of a foreign corporation, 100% dividend received deduction allowed (foreign portion of the dividend). | No | N/A |

|

Source: Deloitte International Tax Highlights 2021, https://dits.deloitte.com/#TaxGuides; Bloomberg Country Tax Guides 2021, https://www.bloomberglaw.com/product/tax/toc_view_menu/3380; EY Worldwide Corporate Tax Guides 2021; PwC Worldwide Tax Summaries, https://taxsummaries.pwc.com/. |

||||

| CFC Determination | CFC Rule Applicability | Income Assessable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | CFC Regime? | Year Implemented | Shareholding Requirement | Corporate Tax Requirement | Income Type Requirement | Other Application Metrics or Exemptions | Type of Income Taxed If CFC Rules Apply |

| Australia | Yes | 1990 | One of three tests must be satisfied: 1) 40% shareholding for a single entity, no other controlling 2) 50% shareholding for up to 5 shareholders 3) up to 5 shareholders have effective managerial control. | None | 5% passive (tainted) | Status as an “unlisted” country. If passive income and tainted sales and services income are less than 5% of total income then no CFC inclusion. “Whitelist” countries CFCs only include certain passive income. | Passive |

| Austria | Yes | 2019 | 50% through either direct or indirect ownership (profits, shares, or voting rights). | 12.5% effective rate | 33% passive | CFC with substantive economic activities exempted. | Passive |

| Belgium | Yes | 2017 | 50% through either direct or indirect ownership (capital, profits, or voting rights). | 50% of Belgian effective rate | Income from non-genuine arrangements | None | Passive (connected to non-genuine arrangements) |

| Canada | Yes | 1976 | 50% through either direct or indirect means. | None | None | Multiple rules may exempt CFC from taxation. | Passive |

| Chile | Yes | 2014 | 50% through either direct or indirect means or bylaws can be unilaterally amended by the Chilean entity. | 30% of Chilean effective rate | 10% passive; 80% passive triggers full inclusion | The passive income is less than 10% of the total profits; the value of the assets of the CFC that may generate passive income do not exceed 20% of the total value of its assets; or CFC with lower than 30% rate requirement exempt if there is a treaty between third party and Chile. | Generally proportional to passive income |

| Colombia | Yes | 2017 | 10% through direct or indirect means. | None | 80% passive | If 80% or more of total income is passive, then 100% is deemed passive. If 80% or more of total income is active, then 100% is deemed active. | Generally proportional to passive income |

| Czech Republic | Yes | 2019 | 50% through either direct or indirect ownership. | 50% of Czech effective rate | None | None | Passive |

| Denmark | Yes | 1995 | 50% through either direct or indirect ownership. | None | 33 1/3% passive triggers inclusion | None | Passive |

| Estonia | Yes5 | 2000 | Separate rules for natural persons and companies. For companies, 50% through either direct or indirect means (shares, profits, voting rights). | None | Income from fictitious transactions with a purpose to obtain a tax advantage | CFCs in countries that are Estonian tax treaty partners are exempt. A CFC is exempt if the entity has accounting profits of no more than EUR 750,000 and non-trading income of no more than EUR 75,000. | All income from fictitious transactions |

| Finland | Yes | 1995 | 25% through either direct or indirect means (voting, or assets). | 60% of Finnish effective tax rate | Primarily passive | No exemption if CFC is in a blacklist jurisdiction. Exemption applies if CFC is in whitelist jurisdiction (based on exchange of information agreements). Other exemptions apply based on activities and substance. | All income |

| France | Yes | 1980 | 50% ownership requirement through either direct or indirect means. Tax liability owed by single shareholders if portion of attributable profits exceeds 5%. | 60% of French effective tax rate | None | CFC exempt if located in EU or EEA and not an artificial arrangement or if CFC carries out trading or manufacturing (commercial or industrial) activity. | All income |

| Germany | Yes | 1972 | 50% through either direct or indirect means. | 25% of German effective rate | None | CFC exempt if located in EU or EEA and not an artificial arrangement; income amounting to no more than 10% of company’s total gross earnings (if it does not exceed a value of EUR 80,000) is excluded. | Passive |

| Greece | Yes | 2014 | 50% through either direct or indirect means (shares, voting rights, equity, right to profits). | 50% of Greek effective tax rate | 30% passive | Principal shares are not traded on a regulated market; subsidiary located in a non-cooperative state. CFC exempt if located in EU or EEA and not an artificial arrangement. | Passive |

| Hungary | Yes | 1997 | 50% through either direct or indirect means. | 50% of the Hungarian nominal rate | 50% passive | CFC exempt if located in EU, OECD, EEA, and treaty countries and not an artificial arrangement. Accounting profits not to exceed HUF 243,952,500 and non-trading income does not exceed HUF 24,395,250. Accounting profits not more than 10% of its operating costs. | All income associated with non-genuine arrangements |

| Iceland | Yes | 2010 | 50% through either direct or indirect means. | 67% of Icelandic statutory tax rate | None | Exemption if CFC is resident in a treaty country and its income is not mainly financial income. CFC exempt if located in EEA countries, or has a double-tax treaty with Iceland and not an artificial arrangement. | All income |

| Ireland | Yes | 2019 | 50% through either direct or indirect means. | 50% of Irish effective rate | None | Exclusions include: CFC with accounting profits of €750,000 or less. Non- trading income of €75,000 or less. Transfer pricing exemption. Essential purpose test, income that comes from arrangements that do not have the purpose to secure a tax advantage. Several exemptions do not apply if the CFC is in jurisdiction on the EU list of non-cooperative jurisdictions. | All income associated with non-genuine arrangements |

| Israel | Yes | 2003 | 50% through either direct or indirect means; or 40% and together with a relative owns more than 50%; or Israeli resident has veto rights with respect to material management decisions, incl. distributions of dividends or liquidation. Tax liability owed by single shareholders if portion of attributable profits exceeds 10%. | 15% effective rate | Primarily passive | If a resident can make substantial managerial decisions, then an entity can be considered a CFC; resident firm exempt if CFC is publicly traded and 30% or more of its shares/other rights have been issued to the public or listed for trade. | Passive |

| Italy | Yes | 2001 | 50% through either direct or indirect means (voting rights, dominant influence, right to profits). | 50% of Italian effective rate | 33% passive | CFC exempt if located in EU or EEA and not an artificial arrangement; by means of an advance ruling, or the tax audit process, showing that the CFC carries on substantive economic activity. | All income |

| Japan | Yes | 1978 | 50% Japanese firms/individuals through either direct or indirect means; multiple shareholders. Tax liability owed by single shareholders if portion of attributable profits exceeds 10%. | 20% effective rate test except for “paper,” “cash box,” or “black-listed” companies which have a 30% effective tax rate requirement | Passive income must exceed JPY 20 million or passive income share of profits greater than 5 percent | Exemptions exist for economic substance and certain control/location criteria. | Primarily passive (all income of “paper,” “cash box,” or “black-listed” companies) |

| Korea | Yes | 1995 | 50% Korean ownership of voting shares (including relatives or specially related persons who are owners). Tax liability owed by single shareholders if portion of share capital exceeds 10%. | 15% effective rate over the three most recent consecutive years | 50% passive | CFC rules don’t apply to active income if CFC has fixed facilities engaged in business in the foreign country. If annual income is KRW200 million or less, then CFC rules do not apply. | All income |

| Latvia | Yes | 2019 | 50% through either direct or indirect means (capital, voting rights, profits). | None | €75,000 passive | CFC not taxed until profits reach €750,000 or passive income exceeds €75,000. If CFC is incorporated in tax haven limits do not apply. | All income associated with non-genuine arrangements |

| Lithuania | Yes | 2004 | 50% through either direct or indirect means. | 50% of the Lithuanian effective rate | 33% passive | If CFC income is less than 5% of the Lithuanian controlling party income, then there is no CFC taxation. Active income not attributable to parent if establishment requirements are satisfied. EEA and white-listed countries are exempt. | Passive |

| Luxembourg | Yes | 2019 | 50% through either direct or indirect means. | 50% of Luxembourg’s effective rate | None | CFC with accounting profits of no more than €750,000. Accounting profits no more than 10% of the operating costs of the period. | All income from non-genuine arrangements |

| Mexico | Yes | 1997 | 50% through either direct or indirect means; “Management Control.” | 75% of effective Mexican rate | 20% passive | An exemption may apply for non-resident financial entities. | All income |

| Netherlands | Yes | 2019 | 50% through either direct ownership or through an ownership group. | 9% statutory CIT threshold; “low-tax jurisdiction” | 70% passive | An exception applies for companies carrying out substantial economic activities. A minimum substance threshold includes annual salary costs of at least €100,000 and office space that is available to the company for at least 24 months. | Passive |

| New Zealand | Yes | 1988 | 40% for a single shareholder; up to 5 shareholders hold >50%; up to 5 shareholders have significant decision-making power. | None | 5% passive | <10% income interest by individual corporate shareholder. CFC may be exempt from rules if operating in Australia and satisfies other criteria. | Passive |