The debt ceiling debate and looming threat of default is rightly bringing attention to the underlying problem of the federal government’s $31 trillion debt load. Last week, as part of our national debt blog series, we reviewed several studies on what has worked internationally and historically in terms of sustainably reducing debt with minimal harm to the economy, finding that reducing spending is key (sooner rather than later) and raising revenue from relatively non-distortionary sources like consumption taxes can also contribute to success. This week, we will provide a more general picture of how U.S. debt compares across countries and discuss some of the downsides of high debt levels.

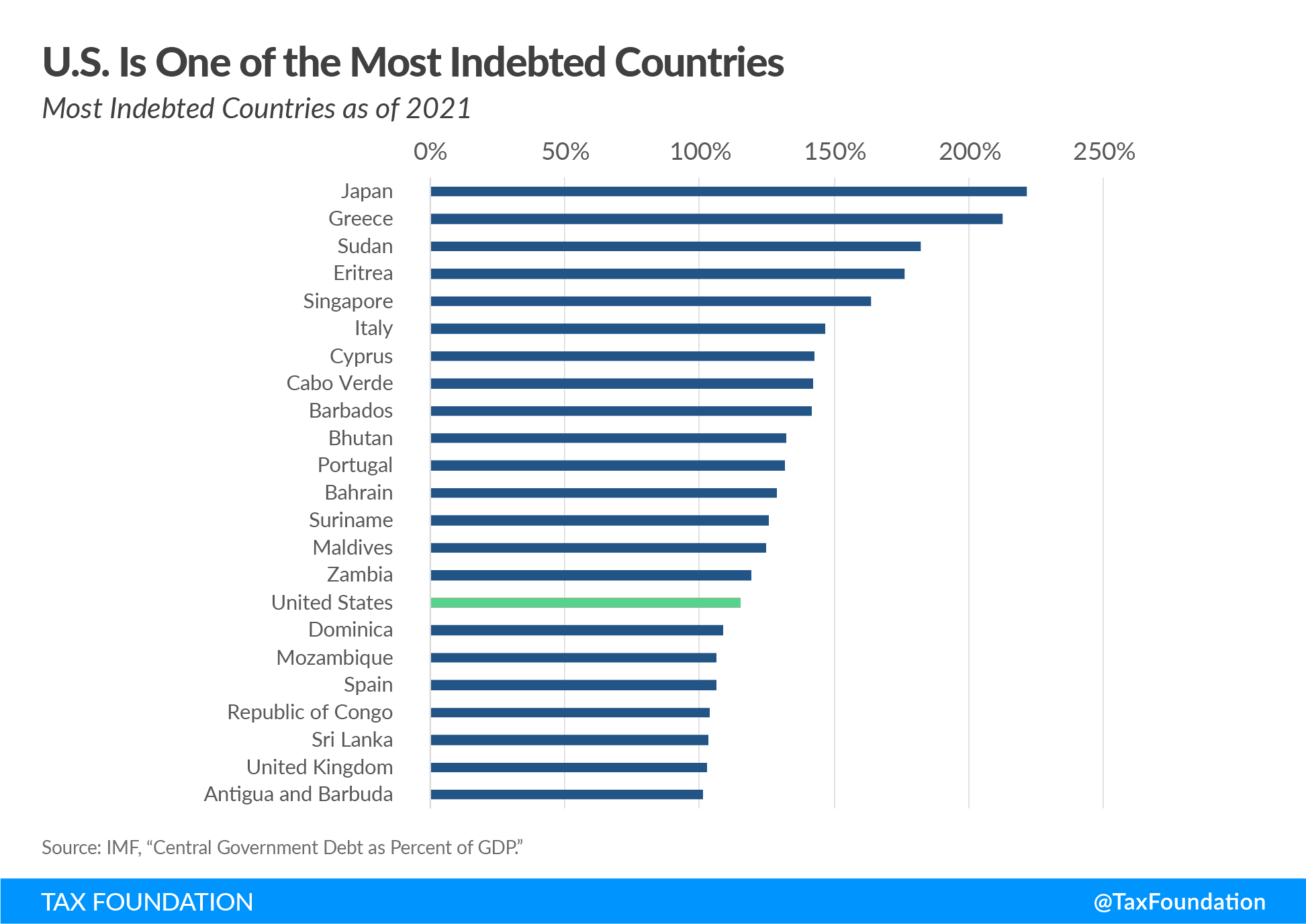

According to the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) measure of central government debt, the U.S. federal government is among the most indebted governments in the world. As of 2021 (the latest available data), federal debt reached 115 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), ranking 16th highest out of 164 countries for which the IMF has data. Japan tops the ranking with central government debt of 221 percent of GDP, followed by Greece, Sudan, Eritrea, and Singapore. Not long ago, the U.S. was among the least indebted countries. In 2001, U.S. federal debt was 42 percent of GDP, lower than debt levels found in 100 other countries.

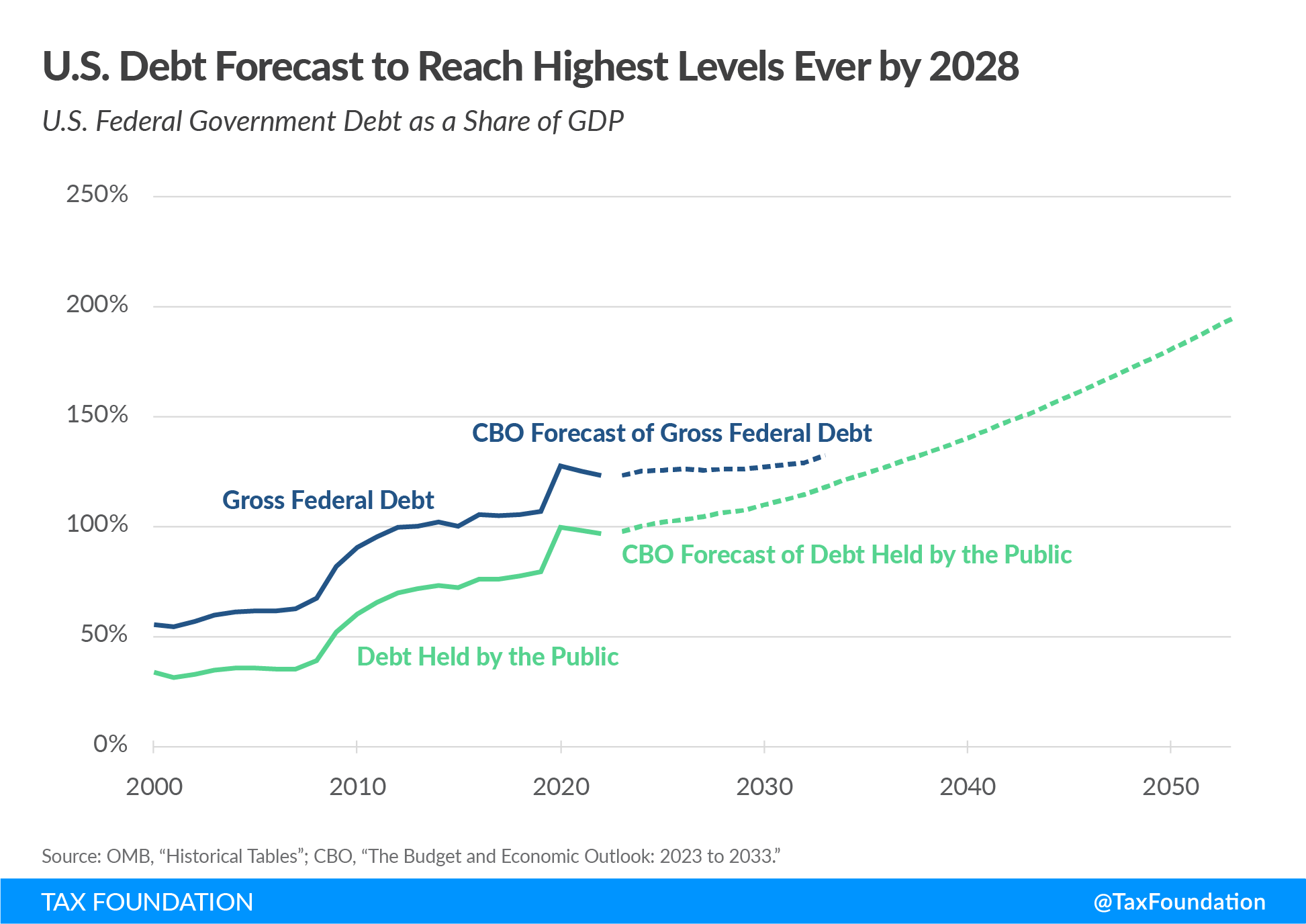

As illustrated in Figure 2, using historical data from the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB), U.S. debt surged upward in two stages over the last 20 years, first after the financial crisis in 2008 and then after the COVID-19 pandemic that began in 2020. Gross federal debt climbed to a record high of 128 percent of GDP in 2020 before falling to 123 percent in 2022. The recent downtick was primarily due to a surge in inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. as well as real economic growth coming out of the pandemic, factors that temporarily reduced debt burdens in many countries.

Even more worrying from a U.S. perspective is the debt to come. The Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) latest forecast projects gross debt as a share of GDP will climb to about 132 percent in 2033. The rapid increase is mainly due to population aging and the rising costs of Social Security and Medicare. (The estimate also assumes no major economic calamities will occur.) Removing debt held by federal trust funds and other government accounts, CBO forecasts debt held by the public will grow from 97 percent last year to 118 percent in 2033—the highest level ever—and will continue to grow to 195 percent by 2053.

The problem may be even worse. Mark Warshawsky and other researchers at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) see rising health-care costs and interest rates contributing to even higher levels of debt. They forecast debt held by the public will grow to 132 percent in 2032 and 258 percent in 2052. Like the CBO forecast, theirs assumes no banking crisis, war, pandemic, or other emergency that might cause a major economic downturn and spike in deficits. As it is, the AEI researchers forecast annual deficits to exceed 6 percent of GDP by 2030 and escalate rapidly thereafter in an unprecedented and “clearly unsustainable” path, around the same time that the Social Security and Medicare trust funds are expected to be depleted.

All of this may seem far off, but the costs of high debt levels are upon us now. They are most clearly visible in the form of high inflation, high interest rates, and slowing economic growth. As John Cochrane, Eric Leeper, Tom Sargent, and other economists have described, the extraordinary surge of federal spending during the pandemic—exceeding $5 trillion through early 2021, or 27 percent of GDP—kicked off a 40-year high in inflation.

That is because the increased spending was not financed by taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. increases; it was financed by debt purchased by the Federal Reserve through money creation. To combat high inflation, the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates to the highest levels in 16 years. That brute force method of slowing the economy through higher borrowing costs has thus far led to heavy losses for investors and several bank failures, among other signs of distress.

High interest rates are also putting pressure on the federal budget, causing interest payments on the debt to crowd out other federal priorities and limiting the federal government’s ability to respond to future crises. According to the CBO, the federal government’s net interest cost will exceed $1 trillion annually by 2029, eclipsing the defense budget.

The financial stress and instability of high interest rates are spreading around the globe, leading the IMF to recommend fiscal restraint as a less economically damaging way to reduce inflation and debt.

Instead, the Biden administration has pushed for the continuation of some of the more costly pandemic-era spending programs, including student loan forgiveness that will add more than $400 billion to deficits over the next 10 years, according to the CBO. And the Inflation Reduction Act enacted last year increased taxes but also increased spending, with current estimates indicating the legislation will worsen deficits on net.

Meanwhile, Republicans and Democrats remain largely unwilling to address the growing cost of Social Security and the major health-care programs, which will consume more than half of the federal budget by 2032, according to the CBO. The demographic factors contributing to the growth of the programs are not uniquely American, as populations are aging rapidly in several countries, especially in Japan and across Europe. There too, pressure is rising on programs that promise benefits for an expanding pool of retirees financed by taxes on a shrinking pool of workers. Economist Eric Leeper describes this dynamic as creating a kind of “insidious” inflationary pressure, as the budgetary imbalance and associated risks grow somewhat imperceptibly over time and the looming policy uncertainty creates costly maneuvering.

Lawmakers should get ahead of growing deficits and debt and provide leadership with sound policy solutions. Our upcoming blog posts in this series will explore options for U.S. lawmakers to reduce debt levels and inflation while supporting long-run economic growth and stability.

Related Resources:

This blog post is the second in a series in which our experts explore the issues and potential solutions for America’s growing debt and deficits.

- Fast Approaching Debt Limit Deadline and Growing Debt Demand Action

- Design Matters When Raising Taxes to Reduce the Deficit and Stabilize the Debt

- Tackling America’s Debt & Deficit Crisis Requires Social Security & Medicare Reform

- Debt Ceiling Deal Reduces Deficits in the Short Term But Delays a More Comprehensive Budget Reckoning

- Testimony: Taxes, Spending, and Addressing the U.S. Debt Crisis

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe