The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 made several changes to the U.S. taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. system to enhance competitiveness and discourage profit shifting to low-tax jurisdictions by U.S. multinationals. Among them were a new 10 percent minimum tax on companies with significant cross-border transactions (BEAT) and new tax rates on deemed intangible income (GILTI and FDII). Foreign profits paid to U.S. parents as dividends were fully exempt from U.S. taxation, moving the U.S. tax system closer to “territorial” tax treatment rather than worldwide. Finally, the top marginal corporate tax rate was reduced from 35 percent to 21 percent.

Altogether, policymakers expected the changes to substantially impact capital flows across borders. Collectively, the changes would reduce incentives to invest in low-tax jurisdictions, as the tax gap between those jurisdictions and higher tax countries would shrink, and potentially shift some of this investment abroad to the U.S.

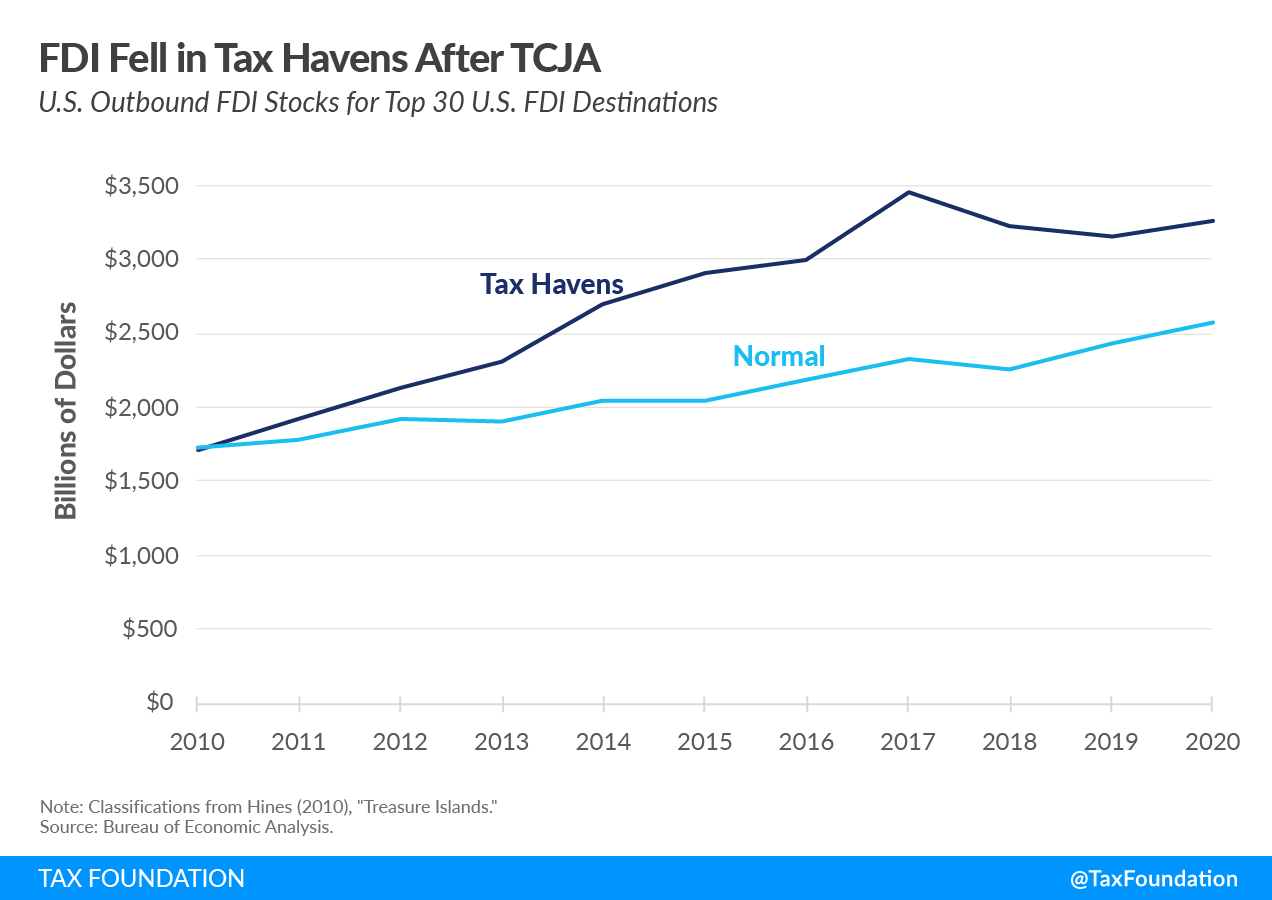

When looking at outbound foreign direct investment (FDI), investment that flows from the U.S. to other countries, we can see the TCJA appears to have had an impact on where companies are investing. The following chart shows trends in FDI stocks for the top 30 destinations of U.S. FDI. Countries are classified as “tax havens” based on research of FDI stocks done by economist James Hines.

Following the TCJA, outbound U.S. FDI stocks fell by $192 billion in the tax havens and rose by $251 billion in the “normal,” or high-tax, countries. The “tax havens” group is comprised of 10 countries or territories, including Ireland, Bermuda, Switzerland, and the Cayman Islands. This trend reflects changes to profit shiftingProfit shifting is when multinational companies reduce their tax burden by moving the location of their profits from high-tax countries to low-tax jurisdictions and tax havens. incentives following the TCJA, as research has found that firms affected by GILTI were less likely to invest in low-tax jurisdictions.

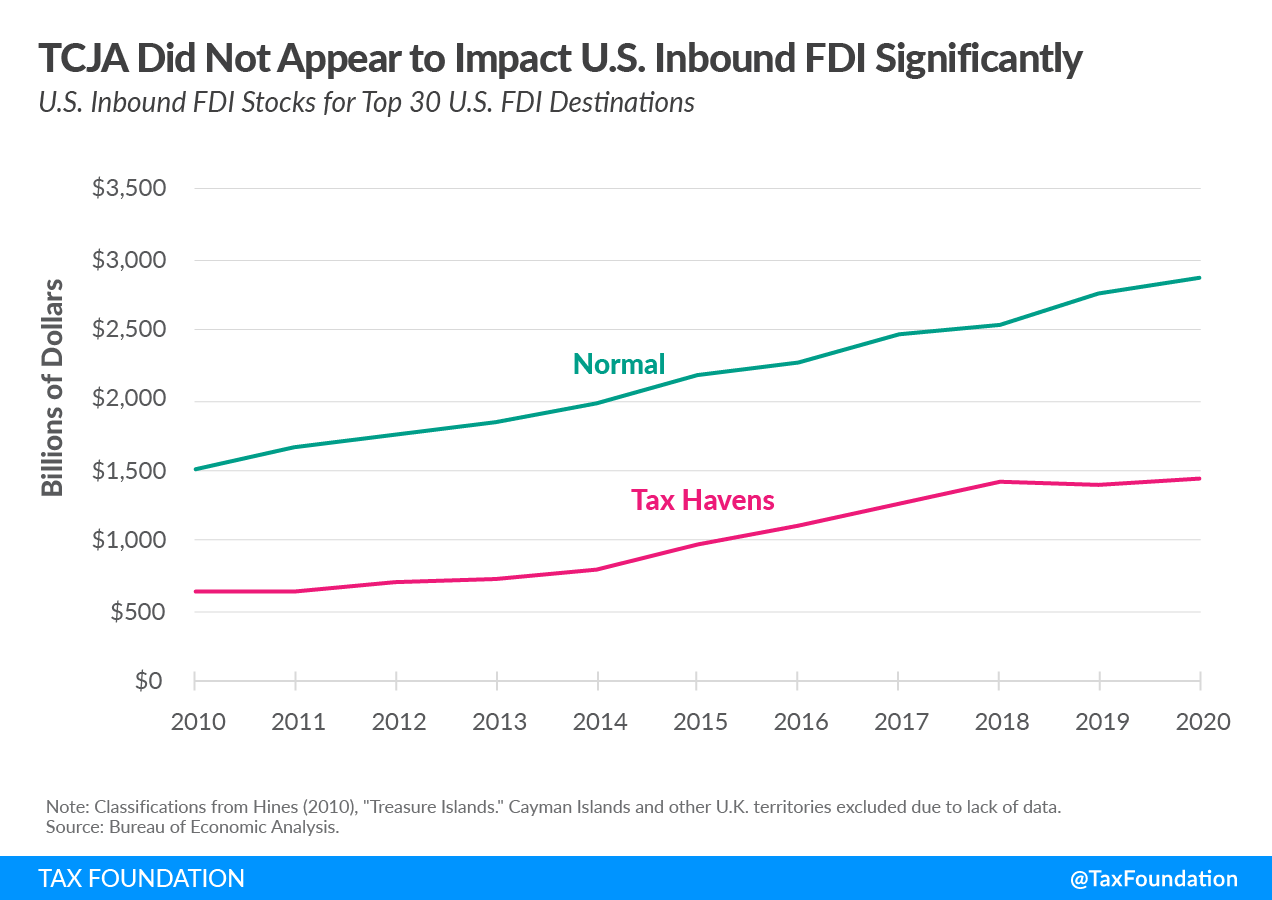

When looking at U.S. inbound FDI across the same set of countries, investment that flows from foreign countries to the U.S., the TCJA does not appear to have caused much of a break in the trends. Inbound U.S. FDI continued to grow at a similar pace from high-tax jurisdictions, while inbound U.S. from the tax havens continued to grow but at a slower rate than it had from 2014 to 2018. Nevertheless, research has found that FDI financed with retained earnings, rather than new equity or debt, was highly responsible to TCJA, with other macroeconomic factors also playing a role in the continued upward trend.

Overall, the data shows outbound FDI shifted from low-tax to other jurisdictions, while inbound FDI remained largely unchanged. But as noted in the first and second of our FDI blog post series, increased foreign activity need not necessarily come at the expense of the U.S. workforce and manufacturing industry. U.S. investment in other countries often generates benefits for the U.S. and helps strengthen supply chains, and policymakers should keep this in mind when trying to raise taxes on cross-border investment.

Note: This is part of our blog series exploring the importance of foreign direct investment (FDI) and its relevance for tax reform.