Key Findings

-

Advances in technology have enabled workers to connect with customers via online platform applications for work ranging from ridesharing to home repair services. The rise of gig economy work has reduced barriers to self-employment, bringing taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. challenges like tax complexity and taxpayer noncompliance.

-

Workers who previously relied on employers for withholdingWithholding is the income an employer takes out of an employee’s paycheck and remits to the federal, state, and/or local government. It is calculated based on the amount of income earned, the taxpayer’s filing status, the number of allowances claimed, and any additional amount of the employee requests. of income and payroll taxes must properly calculate, save, and remit income and self-employment taxes. Gig economy workers are more likely to underreport their income or underpay self-employment tax. One survey of gig economy workers found that 34 percent did not know that they may be required to make quarterly estimated payments to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

-

Most gig economy platforms use a high de minimis threshold for reporting earnings to the IRS and workers, making it more likely that workers fail to meet their tax obligations. Lowering this threshold may help with information sharing of worker earnings and improve compliance rates. One study finds that workers who receive an earnings report increased their reported income by up to 24 percent.

-

Properly tracking and deducting expenses from gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total pre-tax earnings from wages, tips, investments, interest, and other forms of income and is also referred to as “gross pay.” For businesses, gross income is total revenue minus cost of goods sold and is also known as “gross profit” or “gross margin.” is one of the largest challenges for gig economy workers, which can lead taxpayers to accidentally overpay income and self-employment taxes. Taxpayers must determine which expenses may be deducted and divide their expenses between business and personal purposes to calculate taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. , which can be complicated to determine for mixed-use assets such as ridesharing vehicles or rooms for short-term rental.

-

Options for improving the federal tax system for gig economy work include providing a simplified expense deduction, lowering reporting thresholds, and allowing gig economy platforms to voluntarily withhold income and self-employment tax on behalf of their workers. These proposals would lower tax-related barriers to entering gig economy work, but should be weighed against trade-offs such as making the tax treatment of gig economy participants less neutral.

Introduction

Over the past 10 years, workers have increasingly participated in “gig economy” working arrangements, allowing providers and customers of various services—from ride hailing to renting a spare room—to easily find one another through an online platform. The growth of the gig economy allows workers to take advantage of spare capacity in their assets, be it a car or a rental property. The gig economy also gives workers flexibility to earn extra income on their own schedule, as work hours are set by the worker.

The resulting growth in these arrangements has led to discussions about whether existing tax rules can accommodate this activity, and whether gig workers are well-equipped to comply with their tax obligations. For example, there is evidence that gig economy participants often fail to comply with their self-employment tax obligations due to reporting and compliance problems.[1]

This paper provides an overview of the tax challenges gig economy workers face, including compliance-related problems recently highlighted by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and the U.S. Treasury Department. This piece will also consider the role gig economy platforms should play in the tax system as service intermediaries and overview proposed reforms to make tax treatment of gig economy work simpler and more efficient.

By reforming the tax system for gig economy work, policymakers may help make the American economy more dynamic while testing methods to potentially improve the system for all taxpayers.

The Rise of the Gig Economy and Implications for Tax Policy

The lynchpin of gig economy work—sometimes known as the sharing economy—is the rise of smartphone technology, which enables workers to connect with customers through a third-party intermediary, or platform. Gig economy platforms serve as financial intermediaries or marketplace facilitators, enabling payment for services between customers and workers. Gig economy platforms may also set prices for services provided over their applications; for example, ridesharing firms use algorithms to determine the price a customer pays ahead of the ride.

While different kinds of work within the gig economy share common characteristics as a type of freelance work, it can be broken down into four general sectors, each with distinct tax concerns:

- Transportation services, including ridesharing, delivering, and moving services;

- Non-transport service work, such as repair services or dog walking;

- Selling activity, such as selling novelty items or crafts;

- Leasing services, such as short-term rentals, home sharing, and renting parking spaces.[2]

One compelling aspect of gig economy work is the flexibility it provides to workers. Workers decide when to work and how long they work, adjusting their work time to fit with other obligations. About 58 percent of gig economy workers participated in this work for one to three months in the year.[3] Average gig economy earnings per month vary by sector, from $2,113 for non-transport work to $534 for selling activity in 2017.[4] About 83 percent of workers make less than $500 per month working in gig economy arrangements.[5]

The gig economy has reduced barriers to entry for workers who prefer the flexibility that the work entails. Platforms provide the customer base, technical support, marketing, and payment systems that must otherwise be built by the workers themselves, expanding the potential pool of workers. This has led to a growth in freelance and gig economy work over the past 10 years.

Economists disagree over the size of the gig economy. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Contingent Worker Supplement estimates that about 10.1 percent of workers are in “alternative work arrangements,”[6] which is lower than the estimate of about 36 percent found in a survey conducted by Freelancing in America.[7] Some of this disagreement is explained by how surveys define freelance work and whether occasional freelancers are included in the surveys.[8] Of the broader pool of freelance workers, about 4.5 percent of households participated in one or more forms of gig economy work in 2017, up from less than 1 percent of families in 2014.[9]

The growth of the gig economy has implications for tax policy. Many gig economy participants are treated as sole proprietors for tax purposes, which differs from how employee wages are treated in the tax system. Other gig economy workers are treated as landlords and assume responsibilities associated with reporting rental property income and expenses on their tax return. The attendant responsibilities gig economy workers face raises the cost of tax compliance and increases the risk that workers may not properly collect, report, and remit their tax obligations.

Put another way, the current tax regime’s complex withholding, reporting, and expense-related rules may dissuade potential gig economy workers who may not have the knowledge or experience needed to comply with their tax obligations.

Tax Challenges Faced by Gig Economy Workers

The tax system treats gig economy participants as independent contractors when they engage in service work such as ridesharing, moving services, or repair work.

Gig economy participants engaging in leasing activity are treated like other rental property owners in the tax code. These participants have distinct tax challenges compared to independent contractors, though participants in both sectors must grapple with similar problems like income reporting and distinguishing personal expenses from business expenses when determining taxable income.

How Independent Contractors are Taxed

When engaging in service work, most gig economy workers are treated as independent contractors under federal labor and tax law. Common law rules determine if a worker is an employee or independent contractor. This includes whether the business exerts behavioral control over when, where, and how the worker completes their work.[10] The IRS uses a 20-factor test to determine proper classification for tax purposes, separate from the federal tests used for labor law and other state tests.[11]

Other rules include whether the business exerts financial control of the worker’s job, such as by paying a regular wage amount for a set amount of time.[12] Gig economy workers determine their own hours and have a say over which customers they serve while operating on a platform application, like other independent contractors.

For tax purposes, gig economy participants are subject to the same rules as small business owners.[13] This means that, unlike employees, these workers are not subject to tax withholding when earning income. Instead, the workers are responsible for complying with tax laws and are required to allocate funds toward paying their tax liability as they earn income.

If a worker expects to owe $1,000 or more in tax liability, they are required to make quarterly estimated payments on April 15th, June 15th, and September 15th, and the following January 15th annually.[14] These estimates are advanced payments for individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. and self-employment tax liability.[15]

Quarterly estimated payments are a common source of confusion for workers in the gig economy: in a survey administered by Caroline Bruckner of American University’s Kogod School of Business, about 34 percent of gig economy workers said they did not know that they must file quarterly estimated payments on tax owed over $1,000.[16] Failure to remit quarterly estimated payments may result in underpayment penalties when taxes are filed.[17] A penalty for failing to make estimated payments during the year may apply even when a taxpayer is owed a refund on their income tax return.

There are debates over whether gig economy workers are properly classified as independent contractors, or whether they should be reclassified as employees. Classifying gig economy workers as employees would make these workers eligible for employee benefits, overtime compensation, and other workplace protections.

Self-Employment Tax and Gig Economy Work

In addition to the personal income tax, the federal government levies payroll taxes, which for employees are paid by both the employee and employer. Under current law, employees pay 6.2 percent on wages earned up to $132,900 in 2019 under the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA), while employers also pay 6.2 percent.[18]

FICA also enacted a payroll taxA payroll tax is a tax paid on the wages and salaries of employees to finance social insurance programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance. Payroll taxes are social insurance taxes that comprise 24.8 percent of combined federal, state, and local government revenue, the second largest source of that combined tax revenue. of 1.45 percent which is assessed on both employees and employers for a total of 2.9 percent. There is also an additional Medicare tax of 0.9 percent on Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) above $200,000 ($250,000 married filling jointly). This yields a total statutory payroll tax rate of 15.3 percent for wages below $132,900, 2.9 percent for earnings between $132,900 and $200,000, and 3.8 percent for AGI above $200,000 ($250,000 for married filling jointly).

Payroll taxes have a high compliance rate, as both sets of payroll taxes are automatically withheld on behalf of the employee.

Unlike employees, independent contractors must remit both the employer and employee portions of payroll tax in the form of self-employment taxes if the contractor earns $400 or more in net earnings. Contractors calculate and report self-employment tax on Schedule SE of the Form 1040, and are permitted to deduct half of their self-employment tax liability from their gross income before applying individual income tax rates.[19] In other words, taxpayers may reduce their taxable income by one-half of their self-employment tax liability.

There is evidence that gig economy workers have difficulty reporting, calculating and remitting self-employment tax. The U.S. Treasury Department found that “it is likely that self-employment tax underreporting will continue to be a growing problem if not addressed.”[20] This is partly because self-employment tax is not withheld from gig economy workers’ income, unlike employee payroll taxes.

If gig economy workers do not pay self-employment taxes, they fail to contribute to social insurance programs such as Social Security. This has consequences for the funding of the programs and the benefits the workers may be eligible for in the future. In tax year 2014, independent contractors and on-demand workers underpaid about $5.95 billion in Social Security contributions from self-employment tax.[21]

Reporting Thresholds for Gig Economy Earnings

Firms doing business with independent contractors are required to issue a Form 1099 above an earnings threshold. A Form 1099-MISC is used for workers earning at least $600 from a gig economy platform for incentives or bonuses.[22] A Form 1099-K is used for regular earnings, as platforms consider themselves third-party settlement organizations (TPSOs), which are “central organizations that have the contractual obligation to make payments to participating payees of third-party network transactions.”[23]

Both forms provide earnings information to the IRS and the worker, and provide a way for the IRS to match reported data from the platform to a worker’s tax returns. As TPSOs, however, platforms are granted a de minimis exemption before they must issue a Form 1099-K to their workers. Workers must earn more than $20,000 and participate in over 200 transactions before a Form 1099-K is issued on their earnings, though all earnings remain taxable for the worker. Both the earnings and transactions thresholds must be met to exceed the de minimis exemption, which reduces the number of Form 1099-Ks that must be issued.

Most gig workers earn below one or both of the de minimis threshold requirements, which means that the IRS and the worker do not receive reporting information on the earned income from the platform.[24] This means that “contractors under the threshold may lack an important source of information when preparing their tax returns, and the IRS has less information to reference when identifying mistakes” or when finding unreported income.[25]

The lack of reporting on worker earnings lowers compliances rates and reduces federal revenue. Business income is one of the largest sources of lost tax revenue due to noncompliance or underreporting. From 2011 to 2013, about 25 percent of the gross tax gapThe tax gap is the difference between taxes legally owed and taxes collected. The gross tax gap in the U.S. accounts for at least 1 billion in lost revenue each year, according to the latest estimate by the IRS (2011 to 2013), suggesting a voluntary taxpayer compliance rate of 83.6 percent. The net tax gap is calculated by subtracting late tax collections from the gross tax gap: from 2011 to 2013, the average net gap was around 1 billion. —the gap between tax owed and tax remitted to the federal government—is from business income underreporting, totaling about $110 billion annually.[26]

The U.S. Treasury Department has found that about 13 percent of gig economy workers who received a Form 1099-K submitted a Form 1040 without a Schedule SE reporting self-employment tax.[27] This rate is likely higher for workers who do not receive a Form 1099-K. More than 60 percent of surveyed gig economy workers did not receive a Form 1099-K or Form 1099-MISC from a platform in 2015.[28]

Tax revenue from gig economy workers is a form of business income. Federal revenue is reduced when earnings are underreported, or tax liability is not remitted. As University of North Carolina law professor Kathleen DeLaney Thomas points out, “These compliance issues are neither new nor unique. Small business owners have always exhibited low compliance rates compared to wage earners, in part due to opportunity and in part due to the complexity associated with the business tax regime.”[29]

The reporting challenge for gig economy workers is an extension of a broader problem of ensuring tax compliance among small business owners. Tax reporting via Form 1099 may help—there is evidence that workers who receive a Form 1099-K increased filers’ reported receipts by up to 24 percent.[30]

There may also be reporting challenges when taxpayers receive a Form 1099 from one platform but do not receive one from another if they work multiple gig economy jobs. This may confuse taxpayers into thinking only the earnings associated with a Form 1099 are taxable and may incentivize platforms to use the higher Form 1099-K threshold if other platforms fail to send the forms themselves to avoid confusing their workers.[31]

In addition to reporting challenges, gig workers may have trouble interpreting a Form 1099 when calculating income and self-employment tax. Form 1099-K reports gross income inclusive of any fees the platform takes prior to the earnings reaching the worker. If a worker fails to remove these fees from their gross income, they will over-report their earnings and pay more tax than appropriate.[32]

Expense and Deductibility Challenges

After calculating their gross earnings exclusive of platform fees, gig economy workers must account for the expenses related to their work in order to calculate taxable income. Individual income and self-employment taxes apply to net earnings, which makes the proper calculation and deduction of work expenses an important step when calculating tax liability.

Business expenses for gig workers and other independent contractors are “above the line,” meaning that they are deducted from gross income before arriving at adjusted gross income (AGI). This differs from unreimbursed expenses for employees, which prior to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) were deductible from AGI for itemizing taxpayers as “below the line” if they exceeded 2 percent of AGI. Unreimbursed employee expenses are not deductible under current law.[33]

For independent contractors, expenses are entered on Schedule C of Form 1040 when calculating individual income and self-employment tax and are subject to different rules depending upon the nature of the expense. For example, the IRS provides guidelines on the deductibility of vehicle expenses for ridesharing drivers.

Expenses are a major source of tax complexity for gig economy workers. A common feature of gig economy work is using an asset for personal and business use. For example, a car owner may use her personal car for occasional ridesharing work as well. To arrive at net income from gig work, the worker must determine which expenses are deductible for business purposes. Deducting personal expenses would understate a taxpayer’s taxable income, lowering federal receipts.

There is evidence that improper expense reporting is a large source of the tax gap for gig economy workers and small business owners. For example, expense deductions tend to rise when income is reported on Form 1099-K, which suggests that small business owners and independent contractors are improperly adjusting their expense deductions to offset the increased reported earnings.[34][35]

In addition to deductible expenses, the newly implemented pass-through deduction in Section 199A of the Internal Revenue Code provides another deduction for gig economy workers. The deduction provides a 20 percent deduction of qualified business income from federal taxable income, lowering the effective tax rate for some gig economy work and other pass-through businessA pass-through business is a sole proprietorship, partnership, or S corporation that is not subject to the corporate income tax; instead, this business reports its income on the individual income tax returns of the owners and is taxed at individual income tax rates. income.[36] While there are limits to the deduction for higher income taxpayers, most gig economy workers will fall under the threshold where those limitations apply.[37]

Common Causes of Gig Economy Tax Complexity

Two common expense challenges gig economy workers face lie in ridesharing and short-term rentals. Both illustrate the challenges these taxpayers face when calculating expenses and taxable income.

Deducting Vehicle Expenses

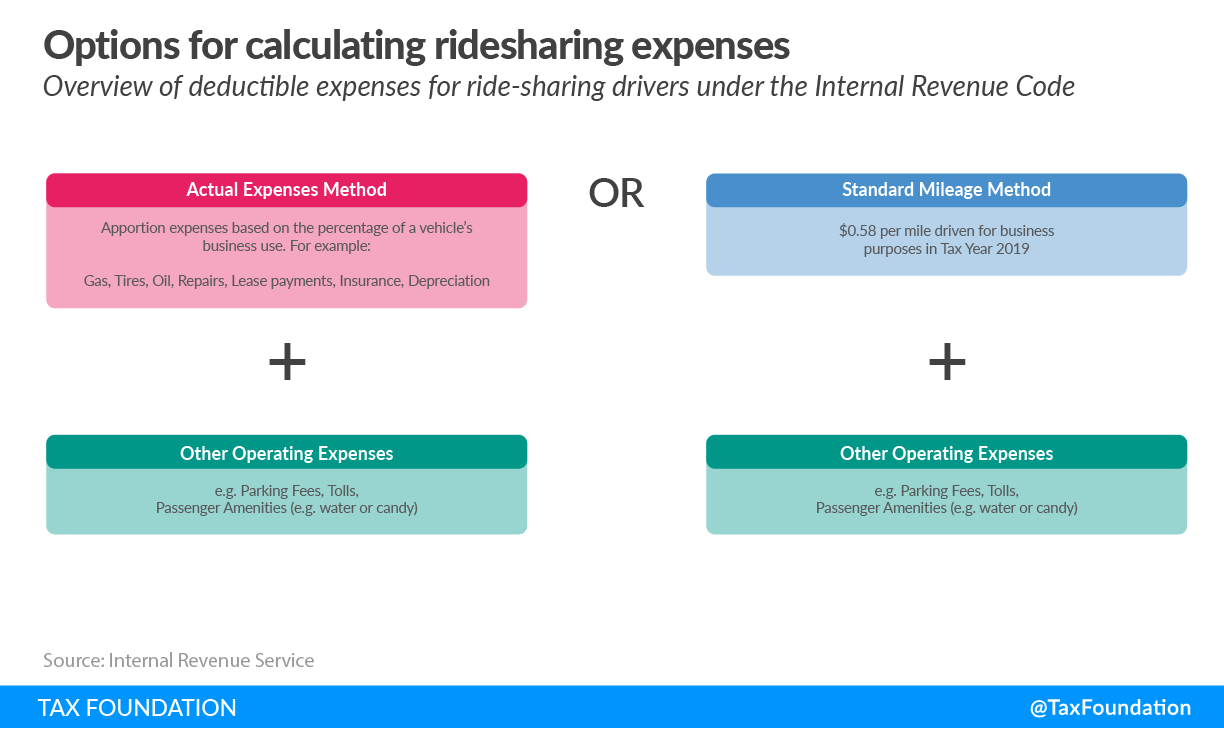

Vehicles are commonly used for business and personal use, and the IRS has rules governing the proper way to deduct business-related expenses. Taxpayers may use either the actual costs method or the standard mileage method for cost recoveryCost recovery is the ability of businesses to recover (deduct) the costs of their investments. It plays an important role in defining a business’ tax base and can impact investment decisions. When businesses cannot fully deduct capital expenditures, they spend less on capital, which reduces worker’s productivity and wages. .[38] The actual costs method requires taxpayers to track the car’s mileage when it is being used for business purposes to determine the appropriate amount of depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. to deduct. They must also track all vehicle-related costs such as gas, oil, repairs, licenses, and insurance.[39]

The standard mileage rate for cars simplifies the expense calculation process. For tax year 2019, taxpayers may claim a $0.58 deduction per mile traveled as the cost of operating a car for business use, but they cannot deduct actual car expenses for that year. Taxpayers may only use the standard mileage method if they used the standard mileage deduction in the first year the vehicle was placed into service for their business. In later years, taxpayers may alternate between the standard mileage deduction and deducting actual expenses.[40] The standard mileage deduction may be taken in addition to deductions for common operating expenses, such as parking fees, tolls, and customer amenities.

The expense tracking process for ridesharing participants can be challenging, partly because of confusion over which expenses are deductible and how to accurately track deductible mileage. Many ridesharing drivers track mileage reported from ridesharing platforms, but these estimates usually understate deductible mileage by not counting mileage accrued when looking for customers.[41]

Another source of confusion when workers determine deductible vehicle expense is what counts as commuting miles, which are not deductible. A ridesharing driver may commute between their residence and when they begin to find customers, and some workers believe that the time driving before finding a customer is deductible.[42]

The tax rules for mixed-use vehicles also limit the value of depreciation deductions if the vehicle is used less than 50 percent of the time for business purposes. If a vehicle is used less than half of the time for ridesharing or other business use, taxpayers must use the more limited Alternative Depreciation System (ADS) over the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) and are ineligible for small business expensing.[43] This means that the value of the vehicle’s deprecation is lower, which is the intent of the provision to prevent depreciation from being taken for personal use.

Deducting Short-Term Rental Expenses

The gig economy has enabled homeowners to rent spare rooms and properties through online platforms. This has expanded the market for short-term rental units while creating a tax challenge for owners who use a room or property for rental and personal use. Rental property owners report their income and expenses on Schedule E of Form 1040.

Expenses cannot be easily apportioned when a property is used for business and personal purposes. Internal Revenue Code Section 280A sets limits on deductibility to clarify the apportionmentApportionment is the determination of the percentage of a business’ profits subject to a given jurisdiction’s corporate income or other business taxes. U.S. states apportion business profits based on some combination of the percentage of company property, payroll, and sales located within their borders. , but still creates complexity for short-term rental owners.[44]

The limit is designed to prevent owners from subsidizing the personal use of their property, as owners would otherwise be deducting property expenses associated with personal use. The limit is triggered if an owner personally uses a property for more than 14 days of a year or more than 10 percent of the time it is rented at fair market value. When the limit applies, property owners may only deduct interest, property taxes, and casualty losses from their gross income.[45]

The limits provided by Section 280A may be confusing to occasional renters, especially when owners are only renting out a room for short-term use. Put another way, “the growth in the sharing economy and options to list shared spaces or private rooms in homes shows that personal and business use increasingly coincide with one another.”[46] This trend has increased the number of taxpayers running into Section 280A limitations and associated complexity.

Economic Consequences of Tax Complexity for Gig Economy Workers

There are economic consequences of tax compliance problems for gig workers. If workers have difficulty determining their tax burden, they may work at a different amount than they would if they had an accurate understanding of their marginal tax rateThe marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. . This “spotlighting” behavior may lead to inefficiently allocated labor supply and lower than expected profits for those workers.[47]

Gig economy workers may work less than they otherwise would if they do not properly track and deduct their expenses. A worker taking fewer expense deductions has a higher tax liability and lower after-tax profit, incentivizing them to work less than they would if they properly deducted their expenses.

Workers tend to estimate their average tax rateThe average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by taxable income. While marginal tax rates show the amount of tax paid on the next dollar earned, average tax rates show the overall share of income paid in taxes. and tend not to “demonstrate awareness of the concept of a marginal tax rate at all and [do] not appear to rely on marginal rates in making driving decisions.”[48] Instead, workers rely on a rough estimate of their average tax burden and gross profitability. In addition to improperly estimating their tax burden, workers are often ignorant of the other components of calculating their tax liability. Nearly half of surveyed gig workers were unaware of tax deductions, credits, or deductible expenses available to them.[49]

If tax compliance costs were reduced, workers may find it easier to determine the tax burden they face on their marginal dollar. In other words, they could make more accurate judgements about whether it is worth it to work a different amount on the margin given their tax burden.

Example of Gig Economy Tax Complexity

The process of holding back income and self-employment taxes from gross earnings, remitting estimated quarterly payments, tracking applicable business expenses, and computing tax illustrates the tax challenges gig economy workers face when compared to employees. While this process may be typical for small business owners, many gig workers are unprepared for how different it is from filing taxes as an employee.

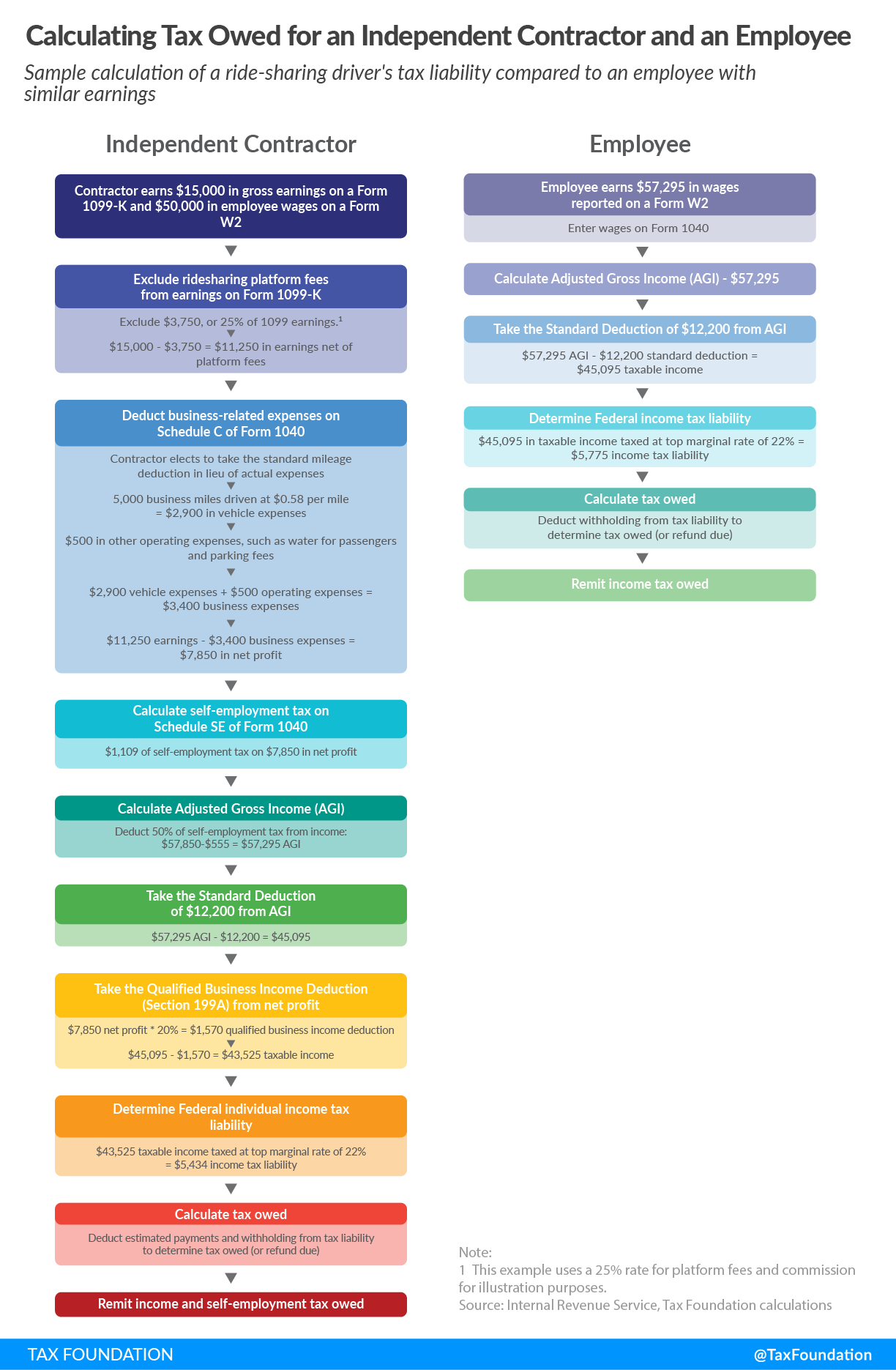

For example, consider a ridesharing driver who earns $15,000 in gross business income driving for a gig economy platform while earning $50,000 in wages from an employer and is filing single. The worker may not receive Form 1099-K, as she is under the $20,000 and 200 transactions threshold for tax reporting. Instead, she uses information the platform provides and her own records to determine her earnings net of platform fees for tax purposes. In this case, the worker excludes $3,750 from gross earnings to arrive at $11,250 in gig economy earnings exclusive of platform fees.[50]

The taxpayer must deduct expenses associated with her gig economy work to calculate taxable income. She must log the miles traveled while ridesharing, excluding miles for commuting and for personal purposes. She must also track any deductible operating expenses such as parking, tolls, and items given to ridesharing passengers. If she drives 5,000 miles and uses the standard mileage deduction, she can deduct $2,900 for vehicle expenses if she takes the standard mileage deduction. She also deducts another $500 for operating expenses for $3,400 in business expenses and $7,850 in self-employment income.

Added to her $50,000 in wages, the taxpayer has a gross income of $57,850, and takes the standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. It was nearly doubled for all classes of filers by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) as an incentive for taxpayers not to itemize deductions when filing their federal income taxes. of $12,200 and may deduct half of her self-employment taxes of $1,109, or about $555. She may also take the 20 percent pass-through deduction on her self-employment income, reducing her taxable income by another $1,570.

Her taxable income of $43,525 is taxed at a top marginal tax rate of 22 percent and yields $5,434 in income tax. She must also remit self-employment tax of $1,109 and pay $3,825 in withheld payroll taxes from her wage income for a total tax federal liability of $10,493 before credits.[51]

The taxpayer may also have to remit quarterly estimate payments if she is expected to owe more than $1,000 in tax from net business income, depending on how much is being withheld from her wages from her employer. Taxpayers may elect to have additional withholding deducted from their wages in lieu of quarterly estimated payments if the withholding covers 100 percent of tax owed in the previous tax year or 90 percent of the tax in the current tax year.[52]

This process becomes more complex if the taxpayer has dependents, is eligible for tax credits such as the Earned Income Tax CreditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. (EITC), or has itemized deductions.

While the tax filing process can also be complex for employees, a similarly situated driver who is employed benefits from employer withholding of income and payroll taxes, reimbursed expenses, and no need to combine self-employment income with wage income when calculating taxes (see example above).

Options for Reforming Tax Policy for the Gig Economy

While there are many options for reforming the tax treatment of gig economy participants, it is important to note that the existing tax system can accommodate most aspects of gig economy work.[53]

As noted above, the tax system already has rules governing how to deduct expenses when calculating taxable income, guidance on properly remitting income and self-employment tax, and separating business and personal use of an asset serviced during gig work.

Instead of a wholesale revisioning of the federal tax code, gig economy participants would benefit most from reforms that simplify tax compliance and clarify their tax obligations. Federal reforms may also help state governments consider ways to improve their tax systems for gig economy work, though state governments face different tax policy challenges.[54]

Three areas of focus for policymakers are clarifying the reporting requirements for gig economy platforms, methods to simplify worker expenses and other deductions from gross income, and removing barriers for platforms to help workers comply with the tax code.

Each area may require a trade-off between simplicity of tax administration and other values such as neutrality and efficiency, and policymakers must weigh how to balance these competing priorities when considering reform options for gig economy participants.

Changing Reporting Requirements for Platforms

One way to close the tax gap among gig economy workers is to clarify which threshold applies to online platforms. Instead of using the Form 1099-K threshold of $20,000 in gross income and 200 transactions, policymakers could lower the de minimis threshold to match Form 1099-MISC, which is set at $600 in gross income.

Lowering the threshold would increase the number of gig economy workers receiving Form 1099 and would help the IRS match the data they receive from workers when they a file tax return. This would also provide policy certainty for platforms, which are currently relying on their own judgment or IRS Private Letter Rulings to determine if they must issue Form 1099-K, which includes the heightened de minimis threshold.[55]

Policymakers should consider the trade-offs involved with lowering the income reporting threshold. A lower reporting threshold would increase administrative costs for online platforms, though this impact may be minimal as most firms are presently issuing Form 1099s to some workers and would just see increased volume.

Lowering the income reporting threshold would only resolve one aspect of the tax gap, as Form 1099-Ks do not track taxpayer expenses or other information, such as tax basis for sold property, that drive tax noncompliance.[56]

Simplifying Expense Deductions for Workers

Simplifying the expense deduction process for gig economy workers would ease tax complexity and improve compliance rates, though at the cost of some neutrality in the tax code.

There is precedent for expense simplification in current law. For example, in addition to the standard mileage deduction, the home office deduction provides a simplified option to calculate office expenses based on square footage.[57] Taxpayers who take this option avoid having to track actual home office expenses and apportion business expenses from expenses related to personal use. A similar approach may be taken for all gig economy expenses, as proposed by the University of North Carolina law professor Kathleen DeLaney Thomas.

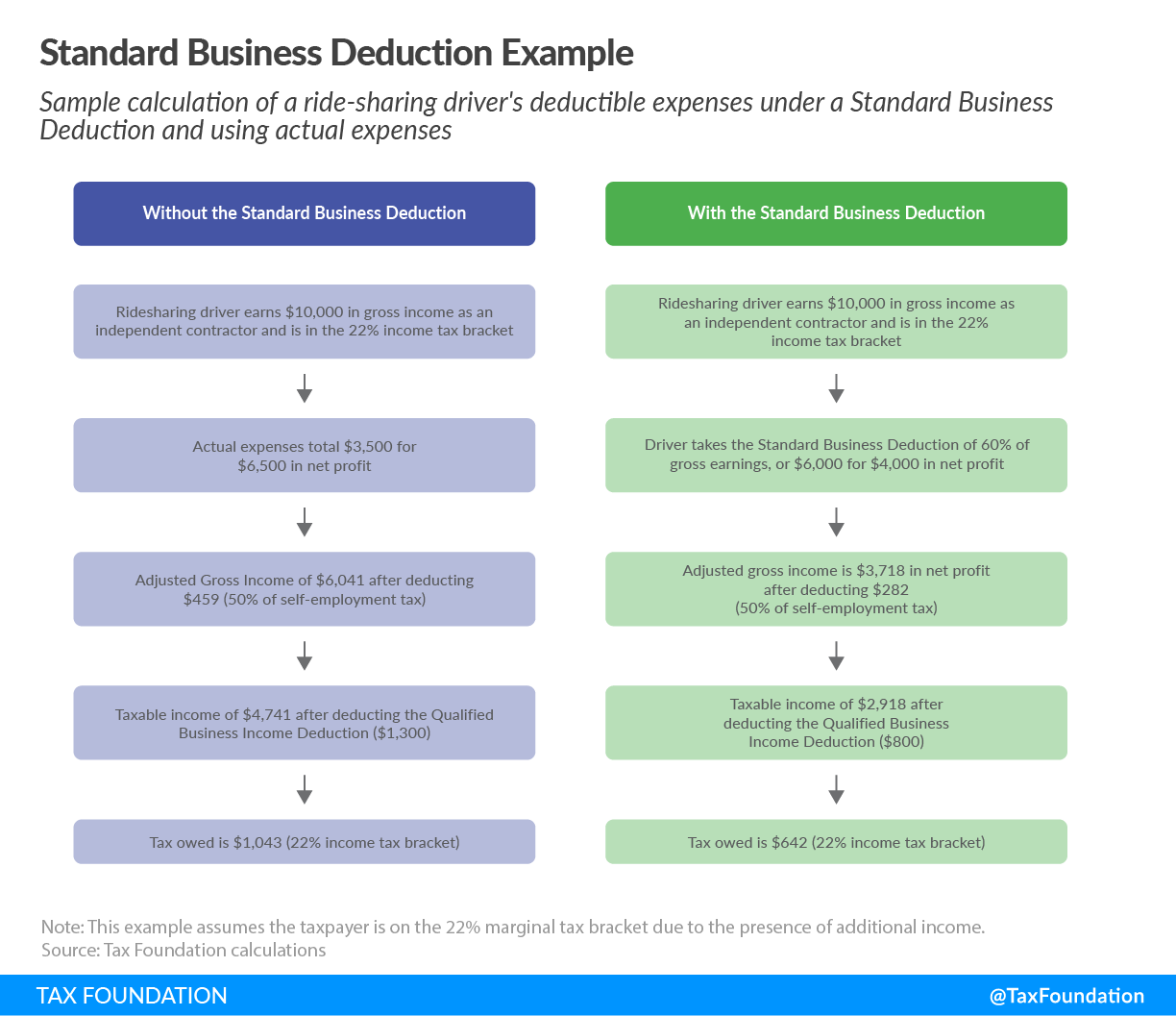

Thomas proposes a Standard Business Deduction (SBD), which would be calculated as a proportion of gross earnings in lieu of actual business expenses.[58] The SBD would eliminate any need to track expense data such as vehicle mileage for tax purposes (though this would be important information to determine economic profitability). A key policy choice rests in what the SBD rate should be—Thomas suggests using industry data to compute average profitability and recommends an SBD of 60 percent of gross receipts.

For example, consider a ridesharing driver who earns $10,000 in self-employment income. If she elects to use the SBD, she would be eligible to deduct $6,000 to arrive at a gross income of $4,000. She may decide to use an actual expense method if expenses were higher and properly tracked.

A 60 percent SBD implies a profit margin of 40 percent, which may vary based on the type of gig work. Policymakers could consider multiple SBDs depending on which industry a worker resides in, at the risk of increased tax arbitrage or gaming if taxpayers seek an improper classification to get a larger SBD.[59]

An important consideration for the SBD is federal revenue loss, as taxpayers would be more likely to take an SBD if it matched or exceeded actual expenses. This could be offset, however, from reduced administrative and monitoring costs on behalf of the taxpayer and tax authorities.[60] An SBD may also be combined with a tax withholding regime for gig economy workers (see below).[61]

The standard mileage deduction and simplified home office deduction are precedents for an SBD, though the standard mileage deduction still requires expense tracking that the SBD would eliminate. An SBD would expand the benefits of these simplified deductions to gig economy workers outside of ridesharing, though the SBD may need to be adjusted to reflect the specific circumstances of property owners or those selling goods via a platform.[62]

A successfully implemented SBD in the gig economy could expand to other sources of self-employed income. However, policymakers must consider the trade-off between tax simplicity and tax neutrality. A simplified expense deduction may treat similar taxpayers differently if they have different profit margins. An opt-out option can help alleviate some neutrality problems for taxpayers with lower margins.

Safe Harbors and Worker Classification

Conversations about tax reform in the gig economy will be closely linked to the proper worker classification of gig economy workers. Short of an overhaul of current worker classification rules, policymakers could enable online platforms to help workers comply with the tax code.

Gig economy platforms are limited in how they may offer tax advice due to worker classification rules. Similarly, they may not offer services such as voluntary withholding arrangements, as this may risk a worker classification lawsuit from a worker or the government.

The New Economy Works to Guarantee Independence and Growth Act or NEW GIG Act, proposed by U.S. Senator John Thune (R-SD), seeks to add certainty to the worker classification rules by creating a safe harbor for determining if a gig economy worker is an independent contractor. The safe harbor would rely on three objective tests demonstrating the independence of gig economy workers, simplifying the current 20-factor test currently used by the IRS.[63]

Another reform option would permit platforms to voluntarily withhold income tax on behalf of gig workers without risking a challenge to the worker’s classification as an independent contractor.[64] This change would preserve the flexibility the classification entails while reducing the cost of tax compliance for workers. Offering a method of simplified tax withholding may also be a way for platforms to compete for workers.

Voluntary withholding for independent contractors may be challenging to administer using existing withholding tables, as workers are more likely to have income coming from multiple jobs and must account for expenses. One approach could derive proper withholding by asking the worker to project their annual business income and using a fixed estimate of profitability, like the Standard Business Deduction.[65] This information would be used to withhold based on an estimate of net income in a pay period, and could be adjusted if the estimated income changes.

Conclusion

The flexibility and low barriers to entry associated with the gig economy has enticed millions of workers into independent contracting arrangements. Tax authorities have a growing sense of the gig economy’s tax challenges. For example, the IRS recently created the Sharing Economy Tax Center to help gig workers understand their tax obligations.[66]

While the federal tax system has the major pieces in place for gig economy participants to calculate their tax liabilities, policymakers have an opportunity to reduce the complexity associated with the current system. Paired with education efforts, lowering tax complexity would expand the gig economy’s benefits to workers who would otherwise avoid that kind of work while raising compliance for current gig economy participants.

When considering potential reforms, policymakers should weigh the trade-offs, such as departing from economic neutrality or adding administrative costs onto gig platforms. A multi-stakeholder approach involving taxpayers, platforms, tax authorities, and policymakers will be needed to ensure that gig economy work remains dynamic and provides opportunity for its participants.

Acknowledgement: The author thanks the Tax Institute at H&R Block for support of this publication. All opinions expressed are those of the author.

References

[1] U.S. Treasury Department Inspector General for Tax Administration, “Expansion of the Gig Economy Warrants Focus on Improving Self-Employment Tax Compliance,” Feb. 14, 2019, 6, https://oversight.gov/sites/default/files/oig-reports/201930016fr.pdf.

[2] Diana Farrell, Fiona Greig, and Amar Hamoudi, “The Online Platform Economy in 2018: Drivers, Workers, Sellers, and Lessors,” J.P. Morgan & Chase Co. Institute, September 2018, 6,

https://institute.jpmorganchase.com/institute/research/labor-markets/report-ope-2018.htm.

[3] Ibid., 3.

[4] Ibid., 4.

[5] Abha Bhattarai, “Side hustles are the new norm. Here’s how much they really pay,” The Washington Post, July 3, 2017, https://washingtonpost.com/news/business/wp/2017/07/03/side-hustles-are-the-new-norm-heres-how-much-they-really-pay/.

[6] Those in alternative employment arrangements include independent contractors, on-call workers, temporary help agency workers, or workers provided by contract firms. See Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Contingent and Alternative Employment Arrangement Summary,” June 7, 2018, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/conemp.nr0.htm.

[7] Adam Ozimek, “Why Estimates of the Freelance Economy Disagree,” Upwork, August 2019, https://upwork.com/press/economics/upwork-freelancer-estimates/.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Farrell, Greig, and Hamoudi, “The Online Platform Economy in 2018,” 3.

[10] Internal Revenue Service, “Employer’s Supplemental Tax Guide,” Publication 15-A, 2019, 7, https://irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p15a.pdf.

[11] Diane M. Ring and Shu-Yi Oei, “Tax Issues in the Sharing Economy: Implications for Workers,” in Nestor M. Davidson, Michèle Finck, and John J. Infranca (eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of the Law of the Sharing Economy (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press), January 2019, 5, https://works.bepress.com/diane_ring/162/.

[12] Ibid, 8.

[13] Caroline Bruckner, “Shortchanged: The Tax Compliance Challenges of Small Business Operators Driving the On-Demand Platform Economy,” Kogod Tax Policy Center, American University, May 23, 2016, 3,https://american.edu/kogod/news/shortchanged.cfm.

[14] The $1,000 tax liability estimate is calculated after subtracting any additional employer withholding and refundable tax credits.

[15] Caroline Bruckner and Annette Nellen, “Failure to Innovate: Tax Compliance and the Gig Economy Workforce,” Tax Notes, May 6, 2019, https://taxnotes.com/tax-notes-state/tax-cuts-and-jobs-act/failure-innovate-tax-compliance-and-gig-economy-workforce/2019/05/06/29c97.

[16] Bruckner, “Shortchanged,” 11.

[17] I.R.C. § 6654(A).

[18] John Olson, “What Are Payroll Taxes and Who Pays Them?,” Tax Foundation, July 25, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/what-are-payroll-taxes-and-who-pays-them/.

[19] Internal Revenue Service, “Topic No. 554: Self-Employment Tax,” Sept. 19, 2019, https://irs.gov/taxtopics/tc554.

[20] “Expansion of the Gig Economy Warrants Focus on Improving Self-Employment Tax Compliance,” 1.

[21] Caroline Bruckner and Thomas L. Hungerford, “Failure to Contribute: An Estimate of the Consequences of Non- and Underpayment of Self-Employment Taxes by Independent Contractors and On-Demand Workers on Social Security,” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, Jan. 1, 2019, 36, https://crr.bc.edu/working-papers/failure-to-contribute-an-estimate-of-the-consequences-of-non-and-underpayment-of-self-employment-taxes-by-independent-contractors-and-on-demand-workers-on-social-security/.

[22] Internal Revenue Service, “About Form 1099-MISC, Miscellaneous Income,” https://irs.gov/forms-pubs/about-form-1099-misc/.

[23] I.R.C. § 6050W(e).

[24] Garrett Watson, “To Remedy Tax Compliance Problems, Gig Economy Firms Need Policy Certainty,” Tax Foundation, Mar. 1, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/gig-economy-compliance-certainty/.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Internal Revenue Service, “Tax Gap Estimates for Tax Years 2011-2013,” September 2019, https://irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p5364.pdf. The gross tax gap includes taxes not collected and taxes collected via IRS enforcement or other late payments.

[27] “Expansion of the Gig Economy Warrants Focus on Improving Self-Employment Tax Compliance,” 7.

[28] Bruckner, “Shortchanged,” 3.

[29] Thomas, “Taxing the Gig Economy,” 1431.

[30] Joel Slemrod, Brett Collins, Jeffrey L. Hoopes, Daniel Reck, and Michael Sebastiani, “Does Credit Card Information Reporting Improve Small Business Tax Compliance?” Journal of Public Economics 149, May 2017, https://sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0047272717300233.

[31] Ring and Oei, “The Tax Lives of Uber Drivers,” 87.

[32] Ring and Oei, “Tax Issues in the Sharing Economy,” 9.

[33] Thomas, “Taxing the Gig Economy,” 1423-1424.

[34] Slemrod, Collins, Hoopes, Reck, and Sebastiani, “Does Credit Card Information Reporting Improve Small Business Tax Compliance?” 3.

[35] Small businesses and contractors earning over the $20,000 de minimis threshold may be more likely to properly deduct eligible expenses, which could also explain why expense deductions rise when income is reported.

[36] Scott Greenberg, “Reforming the Pass-Through Deduction,” Tax Foundation, June 21, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/reforming-pass-through-deduction-199a/.

[37] Anti-abuse limits begin phasing in for taxpayers with taxable income over $157,500 (or $315,000 for married joint filers). The limits are aimed at these taxpayers working in a specific service-based trade or business. See Ibid., 9-10.

[38] Internal Revenue Service, “Publication 463: Travel, Gift, and Car Expenses,” Mar. 6, 2019, https://irs.gov/publications/p463.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Treas. Reg. §1.274-5(j)(2). The standard mileage deduction is subject to other limitations. For example, taxpayers using five or more cars at the same time (for a fleet) or claiming a depreciation deduction using any method other than straight line depreciation may not use the standard mileage deduction.

[41] Ring and Oei, “Tax Issues in the Sharing Economy,” 9.

[42] Ibid., 80.

[43] I.R.C. § 280F(b)(1).

[44] Aida Vazquez-Soto and Garrett Watson, “Simplifying Complex Income Tax DeductionA tax deduction allows taxpayers to subtract certain deductible expenses and other items to reduce how much of their income is taxed, which reduces how much tax they owe. For individuals, some deductions are available to all taxpayers, while others are reserved only for taxpayers who itemize. For businesses, most business expenses are fully and immediately deductible in the year they occur, but others, particularly for capital investment and research and development (R&D), must be deducted over time. Rules Would Benefit Short-Term Rental Arrangements,” Tax Foundation, June 13, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/short-term-rent-income-tax-rules/.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Diane M. Ring and Shu-Yi Oei, “The Tax Lives of Uber Drivers: Evidence From Internet Discussion Forums,” Columbia Journal of Tax Law 8:1 (2016), 92, https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp/1044/.

[48] Ibid., 93.

[49] Bruckner, “Shortchanged,” 3.

[50] Platform commission and fees are estimated at 25 percent for simplicity. Ridesharing platforms may levy flat booking fees for each ride in addition to a commission, which is usually a percentage of the passenger fare.

[51] This example excludes employer-side payroll taxes.

[52] Internal Revenue Service, “Publication 505 (2019), Tax Withholding and Estimated Tax,” May 16, 2019, https://irs.gov/publications/p505#en_US_2019_publink1000194564.

[53] Ring and Oei, “Can Sharing Be Taxed?” 1008.

[54] For an example of a state tax policy challenge in the gig economy, see Garrett Watson, “Reforming Rental Car Excise Taxes,” Tax Foundation, Mar. 26, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/reforming-rental-car-excise-taxes/.

[55] Watson, “To Remedy Tax Compliance Problems, Gig Economy Firms Need Policy Certainty.”

[56] Leandra Lederman, “Reducing Information Gaps to Reduce the Tax Gap: When is Information Reporting Warranted?” Fordham Law Review 78:4 (February 2009), https://researchgate.net/publication/228220178_Reducing_Information_Gaps_to_Reduce_the_Tax_Gap_When_is_Information_Reporting_Warranted.

[57] The simplified option provides a standard deduction of $5 per square foot of home used for business purposes (at a maximum of 300 square feet). See Internal Revenue Service, “Simplified Option for Home Office Deduction,” https://irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/simplified-option-for-home-office-deduction.

[58] Thomas, “Taxing the Gig Economy,” 1454-1471. A simplified business deduction could also be designed as a flat dollar amount, though this could result in revenue loss for taxpayers with gross receipts at or below the flat deduction who would pay tax under a proportionate SBD. See Ibid., 1462.

[59] Ibid., 1458.

[60] Ibid., 1461.

[61] Ibid., 1469.

[62] For example, the SBD may over-compensate property owners who rent a portion of their property a few times per year, as expenses for property do not necessarily scale with receipts as in ridesharing.

[63] 116th U.S. Congress, “S.700 – NEW GIG Act of 2019,” https://congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/700.

[64] Thomas, “Taxing the Gig Economy,” 1438.

[65] Ibid., 1447.

[66] Internal Revenue Service, “Sharing Economy Tax Center,” Sept. 24, 2019, https://irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/sharing-economy-tax-center.

Share this article