The current coronavirus outbreak has policymakers around the world advancing policies to counteract the economic effects of the crisis. Those economic effects are likely to be severe, and policymakers should consider how the structure of their tax systems might result in deep revenue losses or hamper an economic recovery once the health risks have subsided.

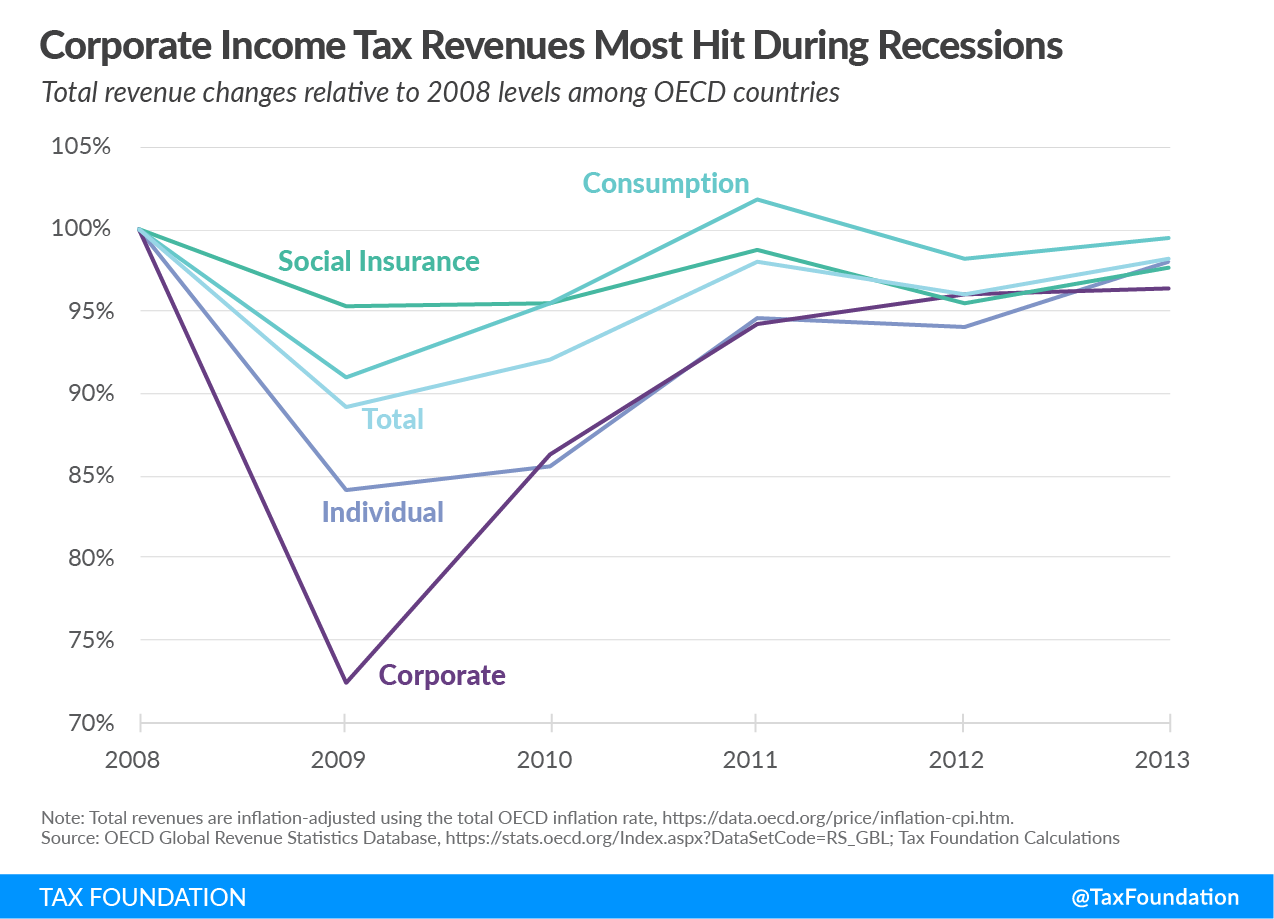

The Great RecessionA recession is a significant and sustained decline in the economy. Typically, a recession lasts longer than six months, but recovery from a recession can take a few years. provides some insight into how taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. revenues declined during a deep recession. Across OECD countries, revenues fell by 11 percent from 2008 to 2009 with corporate income taxes seeing the steepest decline at 28 percent. Revenues from individual income taxes fell by 16 percent.

In contrast, revenues from consumption taxes fell by 9 percent and revenues from social insurance taxes declined by just 5 percent.

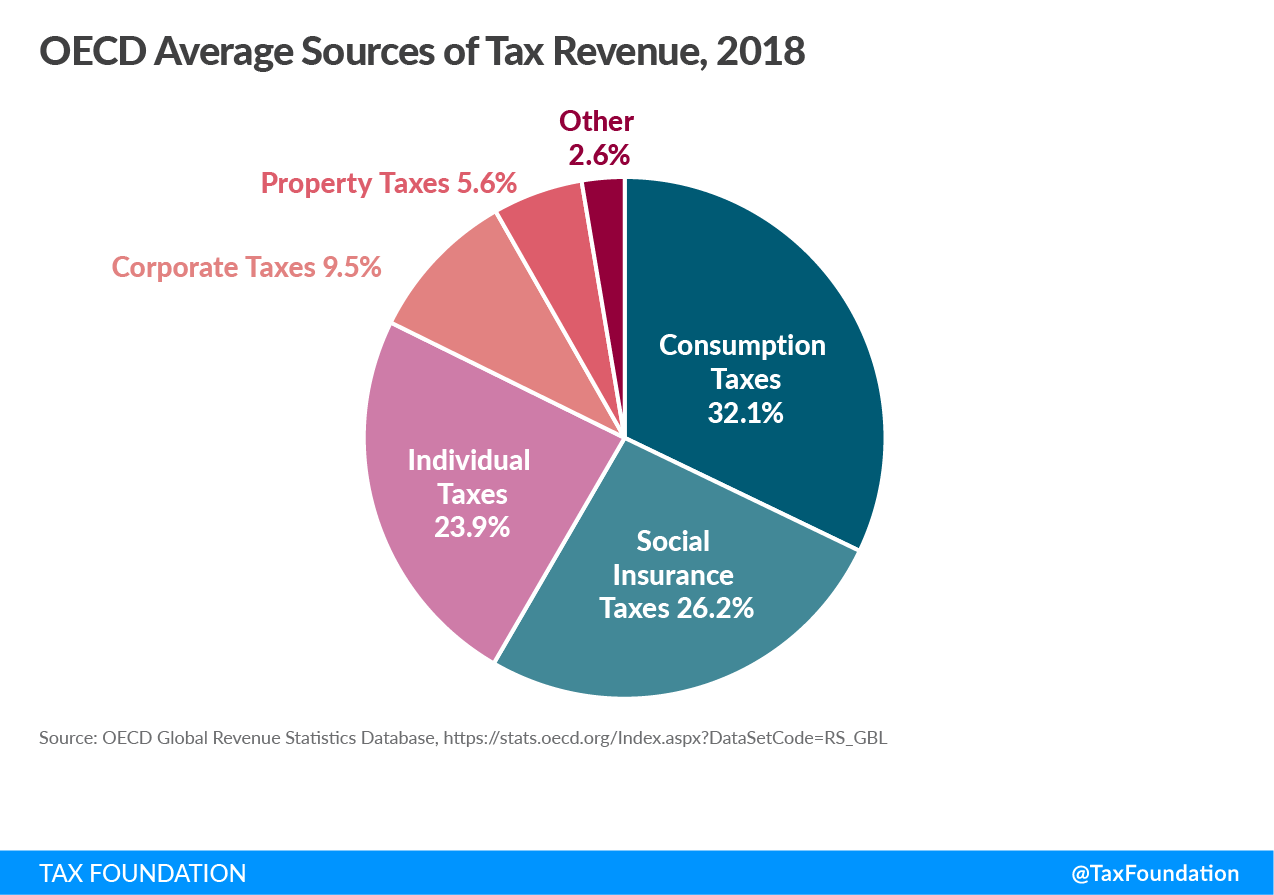

OECD countries rely most on revenues from consumption taxes, social insurance taxes, and individual taxes. But not all countries have the same tax structure, and some tax systems are better designed to confront downturns than others.

Taxes on income are generally more volatile than taxes on consumption, mainly because consumption patterns do not usually face such drastic interruptions as corporate income or personal income. During a recession, workers lose their jobs and businesses run losses, but people will generally continue to purchase the necessary items for their daily lives. The response to the current crisis may result in more dramatic consumption shifts than usual due to business closings and social distancing.

Tax policies that are designed to raise revenue while minimizing their negative impact on investment can also be effective at minimizing the impact of downturns on both revenue losses and the ability for businesses to grow and workers to earn more once the crisis subsides.

For businesses, these policies include unlimited loss carryover provisions and full expensing for capital investments. Unfortunately, these policies are relatively rare among OECD countries. Just 11 OECD countries allow losses to be carried forward indefinitely, and only two—Estonia and Latvia—have full expensing for all capital investments. However, Canada and the United States have temporary provisions for full expensingFull expensing allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of certain investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings. It alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. of machinery and equipment.

A business that runs losses in a recession should be able to deduct those losses against profits when the firm recovers. Loss carrybacks can provide relief during a downturn because businesses can reclaim taxes paid in the past. While carryforwards are good for times of recovery, carrybacks can provide added relief during a crisis.

Additionally, businesses that want to expand their operations and invest once a crisis subsides should not be penalized by the tax code when deducting the costs of those investments.

Many countries are exploring temporary measures as countercyclical tax policy, cutting taxes, and delaying tax payments to address liquidity issues and potentially offset a demand shortfall. To the extent those policies are tried, they will only have an impact that is limited to the current group paying those taxes.

For example, if policymakers choose to reduce the burden of consumption taxes in the face of the current crisis, those changes will only have an impact to the extent that the structure of current consumption taxes interacts with what families buy during and after the crisis.

On average, consumption taxes in OECD countries only apply to approximately 55 percent of consumption. Food at the grocery store is often subject to a reduced or zero value-added tax (VAT) rate already, so cutting the rate wouldn’t provide much relief. Drinks at a bar, which may currently be closed, are usually subject to the standard rate.

Cutting VATs could help consumers, but the scope of that impact will be limited by the narrow-ness of the tax base. Additionally, businesses that operate below VAT registration thresholds will not be impacted by VAT policy changes.

The measures taken to address the spread of the coronavirus outbreak will change consumption behavior and further weaken the effectiveness of policy responses that rely on consumption taxes.

The current outlook for both economic growth and government revenues is not pleasant, and policymakers should be considering how the decisions they make to change their tax systems during the crisis will change how businesses and families navigate the current economic challenges and how the recovery might look.

Share this article