Key Findings

- The U.S. joined many other developed nations in adopting territorial provisions and anti-base erosion rules as part of the 2017 taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. reform.

- One major piece of that reform, that is not typical in other territorial systems, is a new definition of currently taxable foreign earnings, Global Intangible Low Tax Income (GILTI), which is taxed at an effective rate of 13.125 percent, with the rate set to increase after 2025 to 16.4 percent.

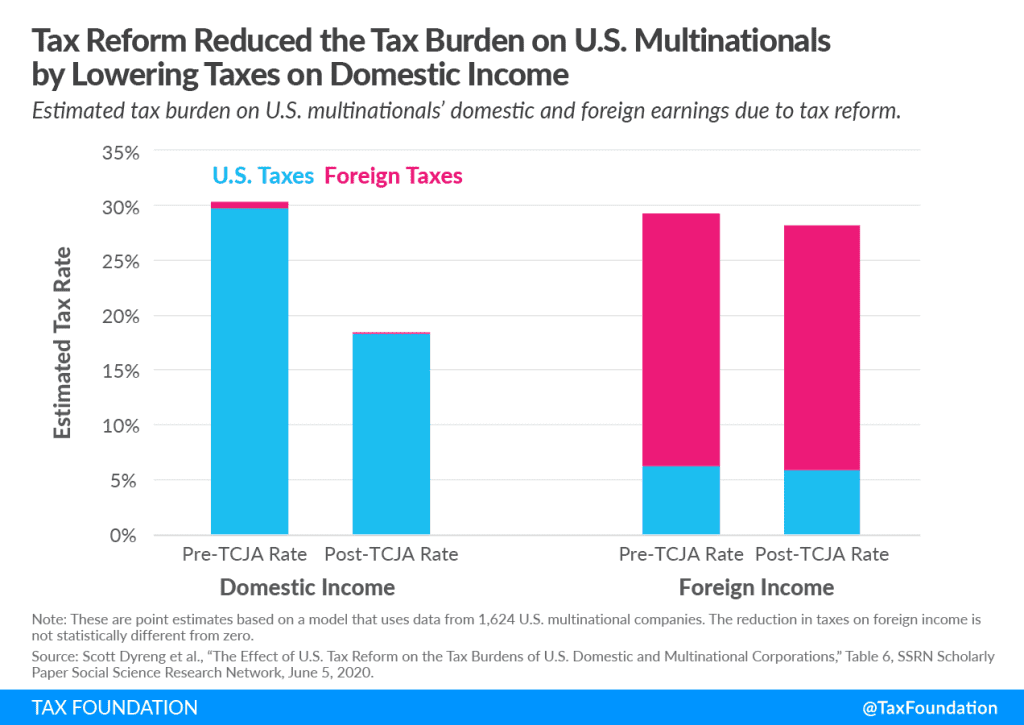

- Recent research has shown that foreign earnings of U.S. companies remain taxed at similar rates even after the 2017 reforms, implying that while the structure of U.S. taxes on foreign earnings changed, the overall burden did not.

- Interactions between existing law and GILTI mean that GILTI targets low-tax earnings while unintentionally placing a higher burden on foreign earnings that already face high levels of taxation.

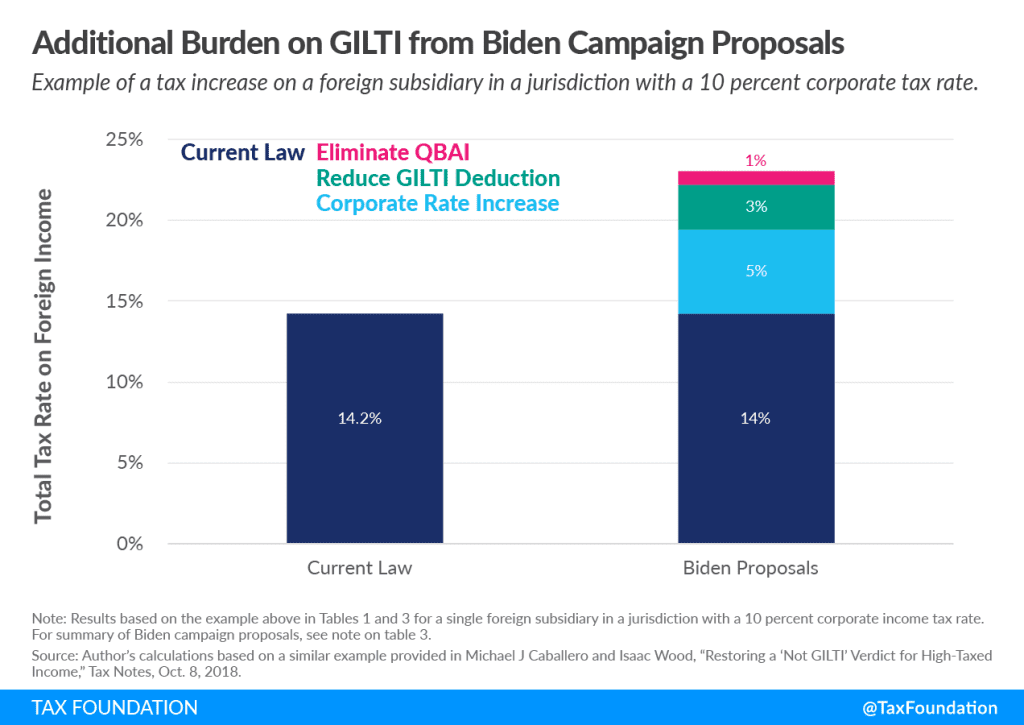

- Changes embedded in the 2017 tax law and proposed by President Biden during the 2020 campaign and by Senate Democrats would increase the tax burden on GILTI for U.S. companies.

- Policymakers should consider ways to ensure the design of GILTI matches its purpose as a backstop to a limited territorial tax systemTerritorial taxation is a system that excludes foreign earnings from a country’s domestic tax base. This is common throughout the world and is the opposite of worldwide taxation, where foreign earnings are included in the domestic tax base. , rather than use it as a template for returning the U.S. to an uncompetitive worldwide tax systemA worldwide tax system for corporations, as opposed to a territorial tax system, includes foreign-earned income in the domestic tax base. As part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the United States shifted from worldwide taxation towards territorial taxation. .

Introduction

Today’s modern economy is made up of businesses that employ workers in countries across the globe, supply chains that cross many borders, and companies with both domestic and international operations. Products designed in one corner of the world are regularly built and distributed in another part of the world.

Such global integration has come with significant advances in technology and medicine that have been critical to maintaining connection and providing solutions during the pandemic. Companies have leveraged access to scientists and labs, programmers, and server farms located around the world.

In today’s globally integrated economy, U.S. companies compete against other firms based in the U.S. and against companies in other countries and continents. Because the tax rules that apply to U.S. companies are different from the rules that apply to foreign businesses, they can have a direct impact on whether U.S. firms can gain or maintain a competitive advantage.

The international success of U.S. companies has meaningful impacts at home. When investing abroad, companies are commonly extending or replicating their operations to reach foreign markets.[1] A U.S. producer that has a successful product in the U.S. might want to reach customers in Europe. To minimize shipping costs, the U.S. company could set up a subsidiary in France to produce its goods for European customers.

The earnings of that foreign subsidiary flow back to the U.S. parent company and its investors, many of whom would likely be U.S. citizens via their retirement savings or pensions.[2] U.S. workers are also likely to benefit from the foreign success of a U.S. company. In 2018, two-thirds of employees for U.S. multinational companies were based in the U.S., representing 22 percent of the U.S. workforce.[3]

When U.S. companies succeed abroad, it can mean more investment in domestic activities and more hiring at home.[4] Research that compares multinational companies to purely domestic businesses has shown that multinationals are more productive and innovative. This is partly because multinationals are engaged in a global market with all the competition and access to a broader information network.[5]

Foreign investment is not only driven by the desire of companies to expand their international footprint. Taxes also influence companies’ investment behavior. A company may choose to locate patents for its technology in a low-tax jurisdiction and then license that technology back to the parent company in the U.S. or to other foreign affiliates in countries with higher tax rates.

Such behavior can be used to facilitate investments in higher tax countries that might not have been otherwise profitable.[6] Tax planning by companies also draws the attention of policymakers who want to ensure that tax avoidance is addressed and that the proper amount of tax is paid to the U.S. Treasury.

A U.S. company that earns profits overseas and then returns its profits to shareholders in the U.S. will have to comply with the tax laws in the foreign jurisdiction and in the U.S. If the U.S. levies a high tax burden on multinationals, it will have a direct impact on their ability to expand and could influence tax planning behavior.

As such, in designing tax rules that apply to multinational companies, one goal of policymakers is to create a system that allows U.S. multinationals to be globally competitive with the expectation of higher returns to U.S. shareholders and domestic investment, while another goal is to discourage tax avoidance.

The U.S. tax system has changed significantly in the past four years as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) enacted in late 2017. Some changes improved the policy landscape for U.S. companies, while others created compliance challenges and new tax burdens that were previously not part of the U.S. tax system.

Prior to the 2017 reform, the U.S. tax system incentivized U.S. multinationals to avoid paying U.S. taxes by artificially shifting income abroad, restructuring as foreign-owned companies, and not repatriating foreign earnings to U.S. shareholders.

The 2017 reforms counteracted these incentives by adopting limited territorial treatment and reducing the corporate tax rate. Policymakers also adopted new rules to minimize incentives for companies to artificially shift profits abroad.

One policy that requires a thorough assessment is the new minimum tax on foreign earnings defined as Global Intangible Low Tax Income (GILTI). This rule has garnered attention because of its unexpected interaction with existing rules and as a target for reform.

When considering recent reforms and potential prospects for future changes, policymakers should consider how U.S. tax rules can contribute to the competitiveness of U.S. companies in their activities abroad and discourage tax avoidance.

Basics of Cross-border Taxation

Cross-border tax rules should be designed to mitigate the chance that companies will pay taxes to two separate countries on the same dollar of income.

Tax rules for multinational companies can fall into two general buckets. Rules that exempt foreign income from taxation are called “territorial” while rules that tax both domestic and foreign income (while providing tax credits for foreign taxes paid) are “worldwide.”

Under a pure territorial system, a U.S. company that earns foreign income would not pay additional taxes on that income when it pays dividends to its U.S. owners via repatriation. The foreign income would be taxed in whatever jurisdiction it is earned. For example, if a U.S. company has a foreign subsidiary in France, the subsidiary would pay taxes according to French rules before paying dividends back to the U.S., which would not face any additional tax in the U.S.

A worldwide system taxes both domestic and foreign income but provides credits for income taxes paid in foreign jurisdictions to avoid taxing the same income twice. Under such a system, a U.S. company that faces a 15 percent corporate tax in a foreign country would receive a credit for the foreign taxes it paid when calculating its tax bill for the U.S. The U.S. would tax the difference between the foreign rate and the domestic rate.

Few countries have pure territorial or worldwide tax systems, however. Thirty-two of the 37 current OECD countries partially or fully exempt foreign income from domestic taxation.[7] So companies only pay taxes on income earned within a country’s borders and qualifying foreign income is exempt. Foreign income that is not exempt is often taxed under policies designed to combat tax avoidance.

Competitiveness

One important consideration when designing tax rules for multinationals is competitiveness. A U.S. company competing against a British firm for market share in Asia can either be helped or hindered by U.S. tax treatment of foreign earnings. If the U.S. has complex rules and high tax rates that apply to income earned overseas while the United Kingdom (UK) does not, then the British firm would have a leg up on the U.S.

If both the UK and U.S. have territorial tax systems that generally exempt foreign income, then the playing field may be relatively equal. Other dimensions of tax rules for multinationals, beyond whether a tax system generally allows for an exemption of foreign income or not, can affect competitiveness too.

For example, the UK may have different ownership requirements for the foreign income exemption. Countries may also differ on rules designed to minimize tax planning.

The totality of international tax rules determines the competitive playing field on taxes for multinational companies.[8]

Anti-avoidance Mechanisms

Tax rules can be designed to address tax planning behaviors that aim to pay low rates of taxes on foreign earnings. Companies that move patents and software (or other so-called “intangible assets”) to foreign subsidiaries in low-tax jurisdictions might be able to pay small amounts of taxes on royalties earned by their intangible assets.

Earnings from intangible assets are usually classified as “passive income,” because after a company develops a new piece of software or a patent, it requires minimal activity to manage the performance of the intangible asset and earn income. Passive income can include royalties, interest, annuities, rents, and dividends.

Intangible assets are an increasingly large share of the value of multinational companies. One estimate suggests that the value of S&P 500 companies associated with intangibles is nine times that of tangible assets.[9] For example, technology companies are valuable because of their software, pharmaceutical companies are valuable because of their patented drugs, and entertainment companies are valuable because of their copyrights. Over the last 20 years, some measures show the value of intangible assets has outpaced the value of tangible assets like factories and equipment.[10]

While intangible assets drive the value of companies, it can be difficult for countries to tax profits derived from them. A company that owns dozens of patents could shift the ownership of its patents to lower-tax jurisdictions more easily than it could shift its factories or workers.[11] For instance, it could shift intangibles from the U.S. to subsidiaries in places such as Ireland, where the corporate tax rate is 12.5 percent, or the Cayman Islands, where there is no corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. .[12] Pricing these cross-border transfers is incredibly difficult and consequential to where and how much a business pays in tax. When businesses can claim deductions or otherwise reduce profits reported in the U.S. while inflating profits in low-tax jurisdictions, the tax base in the U.S. is eroded.

To minimize tax avoidance through international tax planning, countries have designed rules to tax passive income in foreign jurisdictions. The rules fall into a general category of anti-avoidance policies and include controlled foreign corporation rules, thin capitalization rules, and similar measures. [13]

In the recent U.S. tax reform, lawmakers adopted new anti-avoidance policies and incentives that are designed to neutralize the impact of the U.S. tax system on decisions related to intangible assets. How the new rules work will be discussed in greater detail below.

Anti-avoidance policies directly impact businesses by increasing the tax costs connected to various tax planning strategies. They sometimes result in complex rules that make it challenging for businesses to comply and add an extra burden on foreign investment activity.[14] The anti-avoidance policies can also hit some businesses that are not structuring their activities to avoid paying taxes.

The U.S. Cross-border Tax System

The U.S. has what can best be described as a hybrid approach to taxing multinational companies.[15] Rather than being either a true territorial or worldwide system, current rules have elements of both designs including anti-avoidance policies. The 2017 tax reform changed many rules, but some pieces of the old system still exist and interact with the new rules in problematic ways. To understand the current state of U.S. rules, it is worth reviewing how the system worked prior to tax reform and what was changed as part of tax reform.

U.S. Tax Rules Prior to Tax Reform

Before the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) was passed in 2017, the U.S. had a worldwide tax system with deferral. The U.S. corporate tax would apply to the profits of foreign subsidiaries when the profits were paid back to their parent entity in the U.S., something called repatriationRepatriation is the process by which multinational companies bring overseas earnings back to the home country. Prior to the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the US tax code created major disincentives for US companies to repatriate their earnings. Changes from the TCJA eliminate these disincentives. . Companies could defer payments of U.S. corporate taxes by leaving their earnings held by foreign subsidiaries or reinvesting earnings abroad.

The ability to defer provided U.S. companies with a choice. Either leave profits in foreign subsidiaries or repatriate them and pay additional U.S. taxes. The choice was complicated by the high statutory federal corporate tax rate in the U.S., which was 35 percent, one of the highest in the world.[16]

Imagine a foreign subsidiary of a U.S. company that pays taxes in the UK. That subsidiary would face a 19 percent corporate tax rate. If the company were to bring its profits back to the U.S., the company would need to do two things. First, it would need to calculate its foreign tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. for the taxes paid in the UK. Second, it would need to pay an additional 16 percent in taxes, the difference between the UK rate and the U.S. federal rate of 35 percent.[17]

That higher tax burden could easily convince the business that the profits would be better off if they did not face additional U.S. taxes.[18] The company might choose to reinvest its earnings in the UK rather than repatriate them.

If the company did repatriate its earnings, it would have to navigate the foreign tax credit rules.

Foreign Tax Credits

Credits for foreign taxes paid are critical to avoid double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. in a worldwide regime. U.S. rules, however, limit foreign tax credits to the U.S. tax liability on foreign income.[19] The limit is in place because countries have different definitions of taxable income, so U.S. rules for foreign tax credits only allow credits against what the company would pay if their foreign income were subject to U.S. rules.

Think of a U.S. company with a subsidiary in the UK. Prior to tax reform, the U.S. corporate rate was 16 points higher than the UK. Because of the higher U.S. rate, the company would have a strong incentive to maximize its U.S. deductions for expenses related to its UK operations. This would reduce the overall tax burden on the company and specifically reduce taxes owed to the IRS. Foreign tax credit expense allocation rules require some U.S. expenses to be counted against foreign income, however. So rather than deducting its expenses related to its UK income against a 35 percent U.S. federal rate, a share of the company’s expenses would be allocated to the UK for the purpose of calculating foreign tax credits.

Expense allocation rules do not change where the money is spent, though. If the U.S. company spends $100 on research and development activity in the U.S. and $0 in the UK, foreign tax credit rules could still require the company to treat some of its R&D expenses as if they were spent in the UK even though the actual transactions occurred in the U.S.

Because the U.S. taxed worldwide income under the previous system, it was justifiable to require businesses to allocate domestic expenses to foreign entities for tax purposes.[20] The rules matched worldwide income to worldwide expenses to share across entities and limit foreign tax credits.

Through the lens of foreign tax credits, though, a company could appear to owe much less in tax to foreign countries than it paid. The U.S. business with zero deductions in the UK could face the full 19 percent UK corporate tax rate on UK income. Nineteen dollars out of every hundred in income would be taxes owed to the UK. The tax payments would not generate $19 in foreign tax credits, however. Expense allocation rules would shave off a portion of potential foreign tax credits with each allocated dollar.

Taxing Highly Mobile Income under the Old System

Not all foreign earnings faced the same set of rules under the pretax reform regime. Some foreign earnings were taxed by the U.S. whether they were repatriated or not. Subpart F income (named for the relevant section of the Internal Revenue Code, which remains intact after TCJA) includes income that is generally easy to shift. A major portion of Subpart F income is passive investment income such as dividends, rents, interest, and royalties.

Some underlying sources of Subpart F income can be intangible assets which, as discussed earlier, are easier to shift to low-tax jurisdictions than other types of activities.

Rather than being deferred and taxed upon repatriation, Subpart F income is taxed even if it is not repatriated. A U.S. shareholder who owns 10 percent or more of a subsidiary in Ireland would have to report Subpart F income to the IRS even if dividends or royalties earned by that subsidiary remain in Ireland.

Subpart F is designed to ensure that even movable types of income would be taxed by the U.S. The U.S. provides a foreign tax credit for taxes already paid on Subpart F income.

Subpart F does have one feature that has become particularly relevant post-TCJA. If Subpart F income is subject to a tax rate that is at or above 90 percent of the U.S. tax rate, it is exempt from U.S. taxation. The “high-tax exception” makes the policy more targeted to foreign movable earnings that are taxed at a rate significantly below the U.S. corporate tax rate.

Problems with the Old System

The worldwide system with deferral and the high U.S. corporate tax rate was problematic for several reasons, including the incentives it created for companies to keep foreign earnings abroad and “invert”; i.e., move their headquarter locations abroad for tax purposes.[21] The system made the U.S. an outlier among OECD countries and uncompetitive.

Under the previous system, significant (and growing) amounts of earnings were being left abroad, revealing that the U.S. rules were a barrier to returning earnings to the U.S. A Credit Suisse study from 2015 found that S&P 500 companies held as much as $2.1 trillion of overseas earnings abroad, up from $584 billion in 2006.[22] Instead of returning foreign earnings to U.S. shareholders, many companies permanently reinvested their earnings in foreign entities. A 2016 report by AuditA tax audit is when the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) conducts a formal investigation of financial information to verify an individual or corporation has accurately reported and paid their taxes. Selection can be at random, or due to unusual deductions or income reported on a tax return. Analytics found that overseas earnings that had been indefinitely reinvested abroad amounted to $2.6 trillion, up from $1.1 trillion in 2008.[23]

Many U.S. companies also chose to change where they were headquartered through a tax inversion. In a tax inversion, a U.S. company merges or gets acquired by a foreign company and the new company is headquartered in the foreign location. Prior to the TCJA, tax inversions were a regular occurrence, especially for companies in the pharmaceutical industry.[24]

By leading to unrepatriated foreign earnings and tax inversions, the old tax rules for multinationals created both inefficiencies for raising revenue and distortions in business decisions.[25]

Changes Made by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

The TCJA took a new direction for the treatment of U.S. multinationals. Six significant reforms departed from the old system:

- The federal corporate tax rate was lowered from 35 percent to 21 percent.

- A participation exemption was created for foreign-earned dividends (territorial treatment).

- A new reduced tax rate was created for domestic income from intangibles earned from foreign sources (Foreign Derived Intangible Income, or FDII).

- A special minimum tax was imposed on foreign income (Global Intangible Low Tax Income, or GILTI).

- A tax was placed on cross-border expenses between a parent company and its subsidiaries (Base Erosion and Anti-abuse Tax, or BEAT).

- A temporary transition tax was levied on all previously unrepatriated earnings.

The U.S. no longer has a worldwide tax system for taxing corporate income. But it does not have a truly territorial system either. Instead, the U.S. now has a hybrid system with some worldwide taxation, without deferral, for certain foreign income because of GILTI and Subpart F and a tax on certain cross-border transactions. The new participation exemption for foreign-earned dividends is the defining territorial feature of the new rules. U.S. multinationals can now pay foreign dividends to U.S. shareholders without paying U.S. corporate taxes. Qualified dividends are now completely exempt from U.S. tax.

Even with a new system, many old rules were left unchanged. The foreign tax credit expense allocation rules and Subpart F have interacted with the reform to produce some unexpected and unintended consequences.

The New System

The changes that the 2017 tax reform brought to U.S. multinationals can be roughly grouped into three categories. First are changes designed to improve the competitive stance of companies relative to their foreign competitors. Second are new rules to protect the U.S. tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. in the context of the new territorial approach. Third is a transition tax on foreign earnings.

The first group of changes includes the lower federal corporate tax rate, the participation exemption allowing qualifying foreign dividends to be repatriated without additional tax, and the reduced tax rate on foreign earnings from intangibles held in the U.S. (FDII).

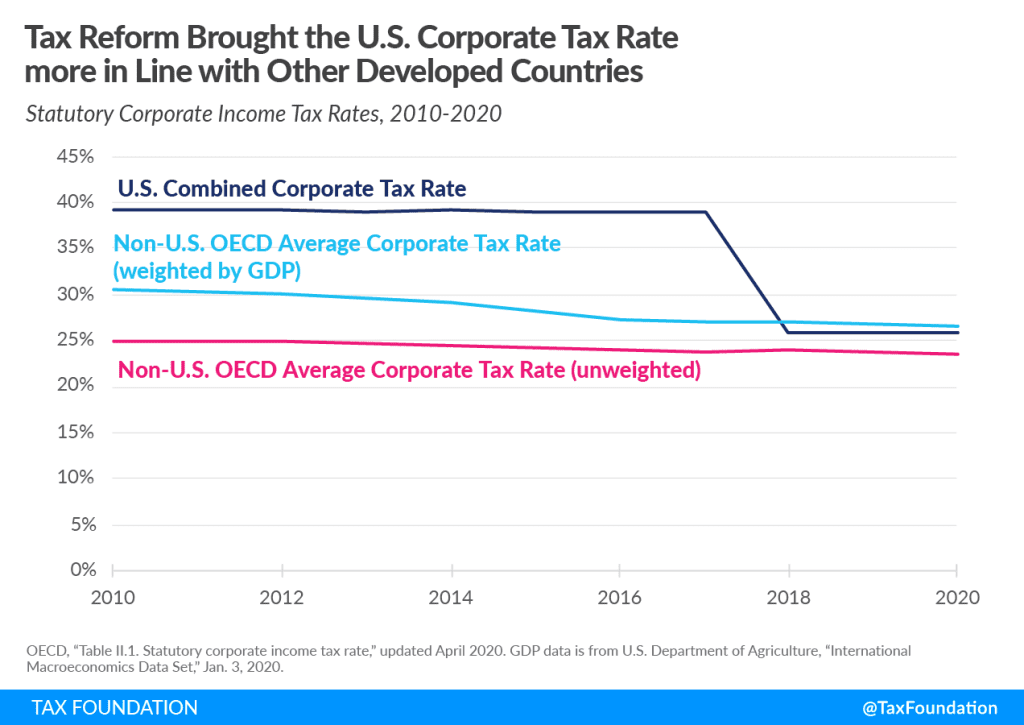

The federal corporate tax rate was reduced from 35 percent to 21 percent which, when combined with state-level corporate taxes, moved the U.S. from having the highest combined corporate tax rate in the developed world to near the average rate.[26] Because corporate tax rate differences are a main driver of tax planning by multinational companies, the corporate tax rate cut significantly changes incentives for multinationals to avoid paying U.S. taxes through various schemes.[27]

The participation exemption (a reform designed to introduce territoriality) provides U.S. companies with direct access to their foreign earnings without the challenges of the previous deferral system. Now a U.S. company can deduct dividends received from its foreign subsidiaries rather than include them in its U.S. taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. . The deduction allows companies and shareholders to redeploy their earnings either domestically or internationally without the distortions of the old worldwide rules.

The new system also creates a tax benefit for firms that hold their intangible assets in the U.S. The FDII rules allow a company that has exports connected to intangible assets held in the U.S. to face a lower rate of tax via a deduction. FDII allows companies a 37.5 percent deduction on eligible income which, at a 21 percent corporate tax rate, translates to a 13.125 percent effective rate on that income.[28]

For intangible earnings, the combination of the lower corporate tax rate, territorial treatment, and FDII serves to provide a tax benefit to companies that hold their intangible assets in the U.S. The new system contrasts with the previous system of worldwide taxation, deferral, and a high corporate tax rate that incentivized companies to place their intangible assets in offshore low-tax jurisdictions.

A business paying low rates of tax on intangible assets abroad before tax reform now has fewer incentives to place new intangibles in foreign jurisdictions. Low tax rates on earnings from intangibles abroad could arise because of low statutory corporate rates or because a company was availing itself of benefits of patent boxes which tax earnings from certain intangible assets at very low rates.[29] Now, instead, the business could choose to keep its assets in the U.S. and pay taxes on its earnings domestically.

Despite these improvements to the U.S. tax system, there was concern that a more territorial system could still create opportunities for U.S. multinationals to earn or report large shares of their income in foreign low-tax jurisdictions. To address these concerns, the TCJA included new guardrails around the territorial provisions. These include the tax on GILTI and the BEAT.

GILTI is a new definition of foreign earnings of U.S. multinationals to which a minimum tax is applied. The tax on GILTI is designed to target passive income from intangible assets. U.S. companies with earnings abroad calculate their GILTI liability each year whether they repatriate foreign earnings or not. GILTI is a companion policy to FDII. The pair of policies potentially eliminates the tax distortion in the choice of whether to keep IP within the U.S. for exporting versus holding that IP in a foreign, low-tax jurisdiction. The tax preference for FDII paired with the tax on GILTI can (in theory) result in a business facing the same tax rate on income from IP whether that IP is held in the U.S. or offshore. The structure of GILTI will be discussed in more detail below.

The second guardrail against abuse of the new territorial system is the BEAT. Like the tax on GILTI, the BEAT is a minimum tax. It is meant to address tax-planning schemes where large multinationals make payments, such as loans or royalties, to their foreign affiliates in low-tax jurisdictions. Since these payments are deductible in the U.S. and the “income” to the subsidiary is taxed more lightly, such payments have been known to “strip” otherwise taxable income out of the U.S. into low-tax jurisdictions. The BEAT rate in 2021 is 10 percent and applies to companies with more than $500 million in total revenues and total cross-border payments that exceed 3 percent (2 percent for some financial companies) of deductions.[30]

The third main piece of the reform package was a transition tax on unrepatriated earnings. The package levied a one-time transition tax on unrepatriated earnings that had built up prior to the TCJA to prevent businesses benefiting from the new system without first paying taxes on old earnings that would have eventually been taxed under the old rules. Foreign illiquid assets (such as factories) were taxed at a rate of 8 percent while liquid assets (such as cash holdings) were taxed at 15.5 percent. The provision allows businesses to pay their transition tax over an eight-year period.

Taken together, tax reform provided rules that generally improved business taxation and competitiveness for U.S. multinationals, but created challenging new rules to mitigate tax avoidance.

How Does GILTI Work?

GILTI is an especially important part of the tax reform package to study for two reasons. First, it is a mirror policy to FDII, and the pair of policies is intended to balance incentives for businesses to keep intangible assets in the U.S. against choosing to place those assets in offshore jurisdictions. Second, the tax on GILTI has created several unintended consequences that have been partially addressed through regulatory actions. Third, the policy was a target for reforms by President Biden’s campaign.[31] Before analyzing what the consequences and reforms look like, it is important to understand how GILTI was intended to work.

GILTI is a minimum tax targeted at foreign earnings from intangible assets. The policy does not target passive foreign earnings directly like Subpart F does by identifying specific types of income to be subject to special rules. Instead, GILTI uses a formulaic approach to tax most active earnings above a 10 percent return on assets even if those earnings are not derived from intangibles. It simply assumes that such “supernormal” returns (i.e., those above 10 percent) are from IP or other intangibles.

If a U.S. company uses a foreign low-tax jurisdiction to avoid paying U.S. taxes, multiple approaches could be used to have that company pay more in taxes to the U.S. Treasury. One would be to require all businesses pay a minimum level of tax on their foreign earnings; GILTI essentially takes that approach. GILTI allows the U.S. to be relatively agnostic about where U.S. companies do business in the world—in high-tax countries or low-tax countries—so long as companies are paying at least a minimum rate of tax on average. To the extent that companies are not paying that minimum rate of tax, the tax on GILTI gives the U.S. the opportunity to charge a top-up tax to ensure the minimum is paid.

Having the minimum rate below the U.S. statutory rate roughly corresponds to policies used by other countries to tax certain foreign income of their companies.[32] In France, foreign income earned outside the European Union (EU) must be subject to at least 50 percent of what would be owed under French tax rules or face additional taxes in France.[33] In Germany, foreign passive earnings from subsidiaries outside the EU or European Economic Area must be subject to at least a 25 percent tax rate to avoid additional German taxes.[34] While the French and German rules are not structured like GILTI (GILTI has a much broader tax base while limiting foreign tax credits), the parallel between the minimum rate rules shows that countries recognize their territorial approaches should be backed up by some form of minimum tax on certain types of income at a rate that is less than the full domestic corporate tax rate.

Some GILTI Basics

To understand how GILTI works and how a company’s liability is determined we first must understand some basic concepts and jargon particular to this section of the tax code. Four such terms stand out:

- Net tested income

- Qualified Business Asset Investment (QBAI) exemption

- The 50 percent deduction

- Foreign tax credit limitation

“Net tested income” is a new term used for determining the income of a U.S. company’s foreign affiliates. It is calculated by adding up the net income and losses of foreign affiliates and is the first step in calculating a company’s GILTI tax liability.[35]

The QBAI exemption is the process of defining, by formula, the above-normal returns that companies are earning on the investments they made in factories, R&D facilities, distribution centers, and other foreign assets of the business. QBAI is calculated by taking 10 percent of the value of a company’s depreciable foreign assets. As we will see in the simplified example below, if a company has $100 worth of foreign assets, then its QBAI deduction would be 10 percent of that amount, or $10.

Our simplified example will also illustrate how the $10 QBAI deduction is subtracted from the subsidiary’s income (“net tested income”) to produce the GILTI tax base. In our example, the net tested income of the subsidiary is $200, so subtracting the QBAI deductions leaves us with a GILTI tax base of $190.

The GILTI tax base is treated differently than purely domestic U.S. profits, which are taxed at the normal federal tax rate of 21 percent. The new TCJA international rules provide companies a 50 percent deduction on that GILTI tax base, essentially cutting the potential GILTI tax liability in half. The result is a minimum tax rate on GILTI of 10.5 percent, which is half of the U.S. statutory tax rate of 21 percent.

The new law’s limitation on foreign tax credits throws yet another wrinkle in this calculation. Under the GILTI rules, foreign tax credits are limited to 80 percent of their value. For many firms, the effect of this limitation is to raise the GILTI tax rate from 10.5 percent to a “maximum rate” of 13.125 percent.[36] Though this limitation creates double taxation of foreign income, the purpose is to discourage some foreign taxes and encourage companies to structure themselves so they pay taxes in the U.S. rather than be indifferent between paying taxes in the U.S. versus paying taxes abroad.[37]

For some firms, even this 13.125 percent “maximum rate” is not the true maximum. As is discussed in greater detail below, the expense allocation rules for foreign tax credits require companies to shift domestic expenses to their subsidiaries, which can further erode the value of the foreign tax credit. If a subsidiary is located in a high-tax country, for example, the combination of the larger allocated expenses with the 80 percent foreign tax credit limitation can make the profits earned in that high-tax country appear undertaxed in the context of GILTI. As a result, a subsidiary’s income that is taxed at foreign rates higher than 13.125 percent can still face additional liability under GILTI.

Foreign tax credits for GILTI are restricted in another way: they cannot be carried forward or back to offset liability in other years. This has the effect of making GILTI liability volatile. A company may have small foreign tax liability and high GILTI liability in some years (like during a new expansion) and high foreign tax liability and low GILTI liability in other years (like when that expansion becomes profitable). Over time, this restriction can lead to higher cumulative U.S. tax on GILTI than if foreign tax credits could be carried forward or back.[38]

Unless a business has all its foreign earnings in a country without a corporate tax system, it will likely have paid some taxes on its foreign earnings. Foreign taxes paid generate foreign tax credits which are limited both by the expense allocation rules discussed previously and by GILTI directly.

A Simplified Exercise in Calculating GILTI

With those basics in mind, let’s walk through a very simplified example of how a company would calculate its GILTI tax liability.

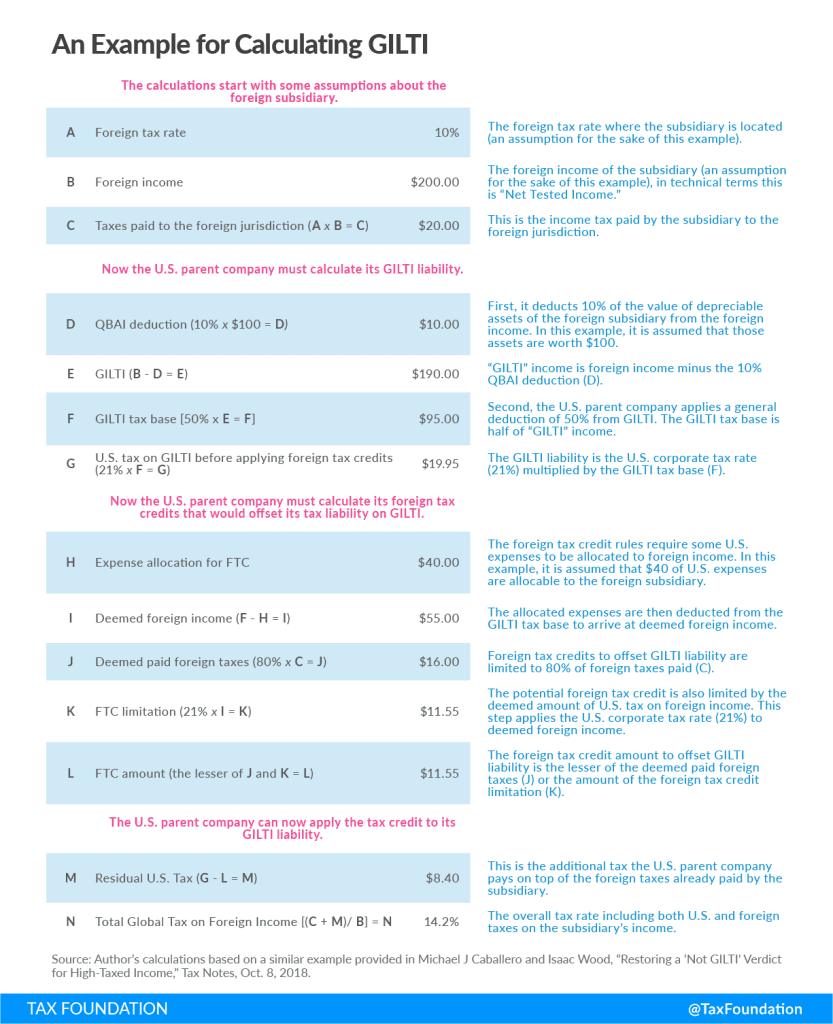

Table 1 shows a simplified example of GILTI calculations for a U.S. company with one foreign subsidiary in a country which levies a 10 percent corporate tax rate. The company has income of $200 and pays $20 in taxes to the foreign jurisdiction.

The company also has $100 in depreciable assets that results in a 10 percent deduction for QBAI of $10. To begin calculating GILTI liability the company subtracts the $10 QBAI deduction from the $200 in foreign income to arrive at $190 in “GILTI” income.

The next step is the 50 percent GILTI deduction. The U.S. only taxes half of GILTI, which for this company is $95. Multiplying the GILTI tax base by the U.S. corporate tax rate of 21 percent results in a tax liability on GILTI of $19.95.

However, because the company has already paid taxes on its foreign income it can offset some of its GILTI liability with foreign tax credits. Even though foreign taxes paid ($20) exceed tax liability on GILTI ($19.95), the company will owe additional U.S. taxes. This is because of the GILTI limits on foreign tax credits and the foreign tax credit rules in general.

To calculate its applicable foreign tax credit, the company must first deduct some U.S. expenses against its foreign earnings. For the example it is assumed that $40 of U.S. expenses are required to be allocated to the foreign subsidiary. Deemed foreign income ($55) is the result of subtracting the expense allocation ($40) from the GILTI tax base ($95).

Separately, the company will calculate its deemed foreign taxes paid which, because of GILTI rules, is 80 percent of foreign taxes paid. The 80 percent haircut means the company will, at most, be eligible for a foreign tax credit of $16.

There is another limit on the foreign tax credit that applies. The foreign tax credit is based on an approximation of U.S. tax liability on foreign income. For this simplified example, that means multiplying the U.S. corporate tax rate (21 percent) by the deemed foreign income of $55, resulting in a foreign tax credit limit of $11.55.

Because the foreign tax credit limit of $11.55 is less than $16 (the deemed foreign taxes paid), the company can reduce its tax liability on GILTI ($19.95) by $11.55, resulting in taxes owed to the U.S. government of $8.40.

The company has now paid $20 in the foreign jurisdiction and an additional $8.40 to the U.S. on income of $200, resulting in an overall tax burden on that income of 14.2 percent.

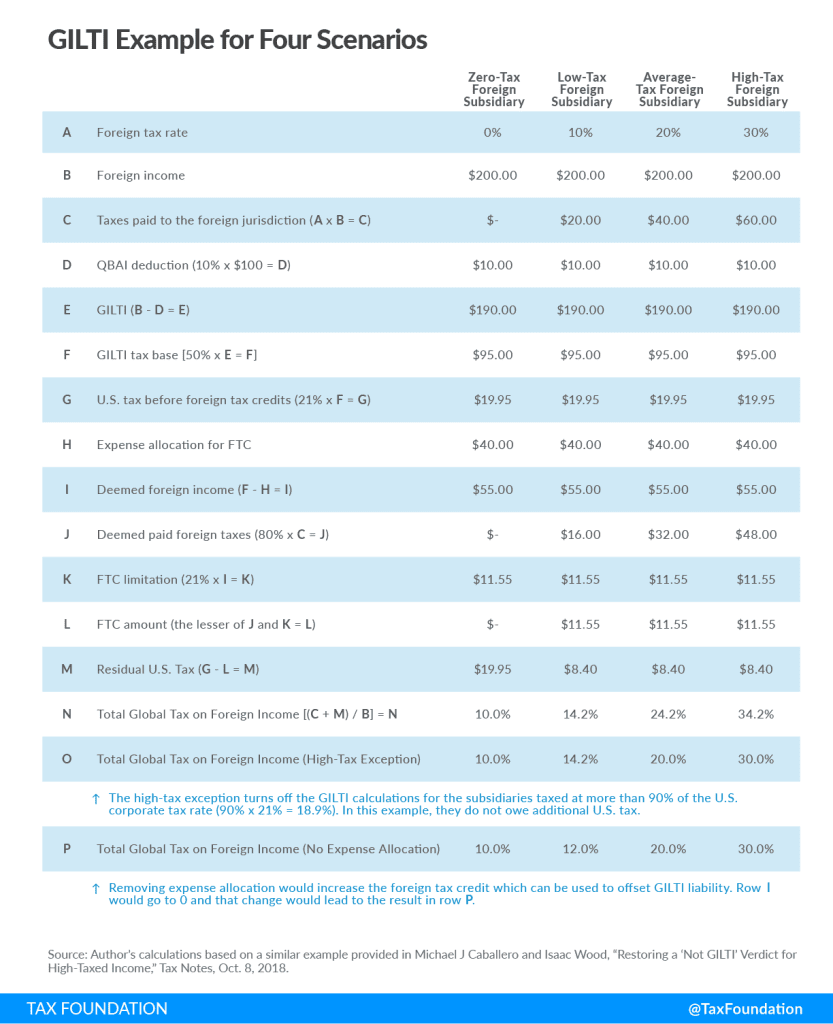

Expanding the Example to Four Subsidiaries

Table 2 shows how the example in Table 1 can be expanded to foreign subsidiaries facing four different foreign tax rates. The assumptions are the same as in Table 1.[39] In the zero-tax scenario, rather than paying no taxes on foreign income, the U.S. company with the subsidiary in the zero-tax jurisdiction pays 10 percent on its foreign earnings. That 10 percent would be owed to the U.S. government. Again, the 10 percent burden is based on total foreign income. The effective tax rate just on GILTI is 10.5 percent.

It is also worth noting that for the foreign subsidiary facing rates above 10.5 percent, GILTI can still have an impact because of the foreign tax credit limits. As discussed, the foreign tax credit requires a calculation of theoretical U.S. tax liability on foreign earnings and is limited by rules requiring domestic expenses to be allocated to foreign earnings.[40] The limitations are in addition to the 80 percent limit on foreign tax credits applicable to GILTI.

In each scenario in Table 2, a U.S. company that owns a subsidiary would be paying taxes to the U.S. government in addition to the taxes it pays overseas (Row M). Even though the high-tax subsidiary pays 30 percent abroad on its earnings, the foreign tax credit limit means additional tax would be owed on its earnings in GILTI. The result is an effective tax rate of 34.2 percent on overseas earnings.

A U.S. company would likely not control just one foreign subsidiary, though. Some firms may control dozens, if not hundreds, of foreign subsidiaries. GILTI allows a U.S. company to blend foreign earnings of multiple subsidiaries into one calculation for GILTI liability. Low-tax income could be blended with high-tax income.

High-Tax Exception

That foreign subsidiaries in average- or high-tax jurisdictions as in Table 2 Row M still owe additional tax under GILTI has generated significant discussion.[41] GILTI, by its name, is targeting low-taxed income. Why, then, should there be additional U.S. tax paid on earnings above the theoretical minimum range built into the tax on GILTI of 10.5 percent to 13.125 percent?

It seemed to the lawmakers who wrote GILTI that there would not be an additional U.S. tax burden if a company paid an average tax rateThe average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by taxable income. While marginal tax rates show the amount of tax paid on the next dollar earned, average tax rates show the overall share of income paid in taxes. on GILTI above 13.125 percent.[42] The impact of the foreign tax credit rules and expense allocation were unforeseen, resulting in calls to ensure that the regulations implementing GILTI could avoid such results. The key underlying problem is the expense allocation rules for Foreign Tax Credits. However, changing the expense allocation rules for GILTI is beyond the scope of Treasury’s regulatory authority under existing law.

This conundrum ultimately led to regulations that provide a path for businesses to exclude high-tax earnings from GILTI.[43] The rules are based on the existing Subpart F high-tax exception allowing foreign income that would otherwise be subject to Subpart F to not face U.S. tax if it is already taxed at or above 90 percent of the U.S. tax rate, or 18.9 percent. While the rules have been subject to debate, the benefits of the exception are limited to businesses that face high foreign taxes rather than the businesses targeted by GILTI.[44]

The exception allows a business to choose to exclude foreign income from its GILTI calculation if the income faces a rate higher than 18.9 percent.[45] The choice can be made annually. Applying the high-tax exception logic results in the high-tax exception rates in Row O of Table 2, where only the earnings from the zero- and low-tax subsidiaries face additional U.S. tax liability.

A company with a foreign subsidiary in each of the categories could calculate its overall GILTI liability by ignoring the two subsidiaries taxed above the 18.9 percent threshold. Even with the high-tax exception, the business would still face additional U.S. tax on the earnings from the lower-taxed subsidiaries.

Expense Allocation and Territorial Taxation

The high-tax exception was brought about because expense allocation rules result in additional U.S. taxes owed by businesses already subject to a high foreign tax rate. Such an outcome raises the question as to why domestic expenses are still required to be allocated to foreign earnings in a territorial system.

Many years prior to tax reform, scholars debated the question. In a worldwide system it makes sense to allocate domestic expenses to foreign earnings so that foreign tax credits apply to a tax base that somewhat matches U.S. tax definitions.

Under a territorial system, however, no similar justification exists. U.S. expenses should stay in the U.S. for tax purposes. If a company has foreign income that is exempt from U.S. taxes, as with the participation exemption, then it should be exempt from expense allocation as well.[46]

The 2011 so-called “Camp Draft,” named after the then-chairman of the Ways and Means CommitteeThe Committee on Ways and Means, more commonly referred to as the House Ways and Means Committee, is the chief tax-writing committee in the US. The House Ways and Means Committee has jurisdiction over all bills relating to taxes and other revenue generation, as well as spending programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance, among others. , Rep. Dave Camp (R-MI), for cross-border tax reforms, followed through on the same logic by only allocating expenses to foreign earnings if they were directly connected to the earnings.[47] So a U.S. company with expenses indirectly related to foreign earnings, such as management costs, would not have to offset foreign earnings for the purpose of limiting Foreign Tax Credits.

If, instead of allocating expenses to foreign subsidiaries, no expenses were allocated, the tax on foreign earnings would be those in the Row P of Table 2. The zero- and low-tax foreign subsidiaries still face additional tax in the U.S., but the foreign subsidiaries facing higher rates would not. The subsidiary in the 10 percent foreign tax jurisdiction faces somewhat lower tax under this scenario because it does owe some foreign taxes.

QBAI Incentives

The example in Table 2 shows how a company might face higher or lower liability on GILTI, other things being equal. Our example assumed that the U.S. company had $100 in foreign assets, which led to a $10 QBAI deduction. But how might the scenario change if the company were to increase its foreign footprint? Some have speculated that the QBAI deduction incentivizes U.S. companies to increase their investments abroad at the expense of domestic investment.

Let’s say a company decided to invest heavily in its overseas operations to increase its QBAI deduction. GILTI liability could fall, albeit by a relatively small amount that might not make the extra investment worth it.

If, in the example above, the company doubled its investment to $200, this would increase the QBAI deduction to $20 rather than $10. As a result, the residual U.S. tax would only be reduced for the zero-tax foreign subsidiary because that subsidiary is not impacted by the foreign tax credit limitations. That additional U.S. tax would only fall by $1.05, however. So, a doubling of foreign assets to increase the QBAI deduction only results in very limited tax benefits under GILTI.[48]

The trade-off may be worth it for some companies that are exposed to GILTI because they own their intellectual property assets overseas but have very few physical assets. For example, a company might normally contract with distribution companies to get their products to customers (warehouses and other logistical capabilities), but to reduce GILTI the company could decide it is better off owning the distribution companies and associated assets. Such a decision would increase their foreign expenses and foreign assets, both of which could reduce additional U.S. taxes paid on foreign earnings.

This is likely the type of activity that is driving the recent research finding on international mergers and acquisitions activity since tax reform.[49] High exposure to GILTI can make acquiring foreign businesses that have depreciable assets and low profitability an attractive option, but this does not mean that businesses will choose to invest in foreign locations when they would otherwise invest in the U.S.[50]

Impacts of the Reforms

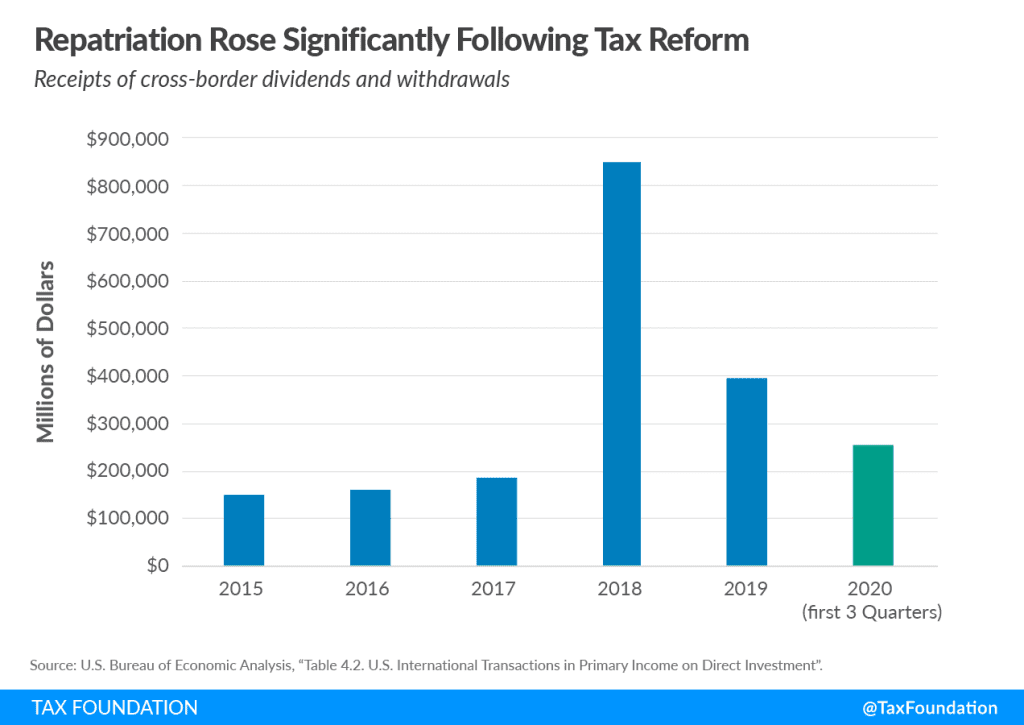

The TCJA reforms have led to several initial results including significant repatriation of foreign earnings and changing patterns of mergers and acquisitions activity.

First, businesses engaged in a major increase in repatriation of foreign earnings to U.S. shareholders. Repatriations via dividends and withdrawals averaged $165 billion annually from 2015 through 2017. Following the adoption of tax reform, repatriations increased significantly. In 2018, $851 billion was returned to U.S. shareholders, a volume 4.6 times larger than in 2017. Repatriations remained at an elevated level through the first three quarters of 2020.

The transition tax also likely contributed to repatriations. Companies with large tax liabilities from the transition tax on unrepatriated earnings may have repatriated foreign earnings to provide liquidity to pay the transition tax.

Second, the new international rules have changed the landscape for mergers and acquisitions. Recent research from accounting professor T. J. Atwood and her coauthors has found that companies more likely to be exposed to the GILTI tax have increased their acquisitions of foreign firms with profits from tangible assets.[51] A firm that has significant GILTI exposure is likely in that position because it earns its foreign income mainly from intangible assets. By acquiring foreign entities with more profits from tangible assets like factories, processing plants, or distribution facilities, a company could dilute its GILTI liability to some extent.

Overall, however, research from accounting professor Scott Dyreng focused on the change in business tax burdens after tax reform has found that domestic companies received a significantly larger tax cut than multinationals.[52] The finding is not surprising since the corporate tax rate was reduced so significantly, and the tax cut received by multinational companies was driven by the change in their domestic tax liability. The tax burden on foreign earnings did not change significantly. Even after accounting for the switch to the new rules, the foreign activities of U.S. multinationals face similar levels of tax as under the previous system.[53]

Other research from economist Kimberly Clausing identifies that the lower corporate tax rate, GILTI, and BEAT reduce incentives to artificially shift income outside the U.S. tax base.[54] She estimates that the reforms will reduce income of U.S. multinationals in foreign low-tax jurisdictions by 12 to 16 percent. This effect will increase taxes paid both to the U.S. and to other high-tax countries.

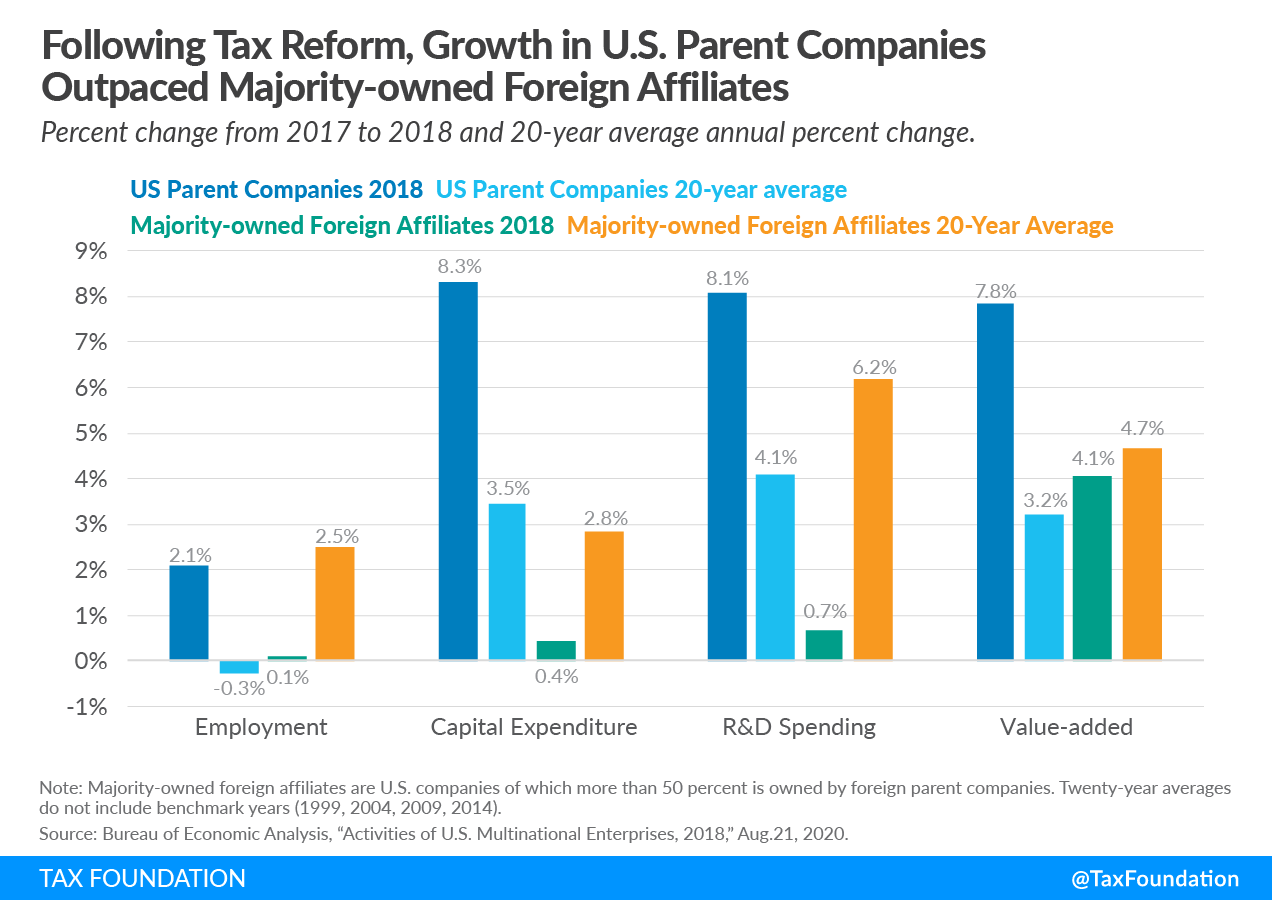

Tax reform was not designed just for short-term results, though. Initial data from 2018 shows promising results for the growth of U.S. companies as shown in Figure 4. Longer-term impacts could emerge in the coming years, especially as the global economy emerges from the pandemic. However, it is important to consider how the international rules were designed and their complexities, particularly GILTI, because the rules adopted in tax reform are targets for changes.

GILTI Changes on the Way

Returning to GILTI, it is important to note that the policy was signed into law with scheduled changes. Without further legislation, the 50 percent GILTI deduction will drop to 37.5 percent at the end of 2025. The change would increase the total tax burden on U.S. companies’ foreign income and increase the number of companies subject to the tax on GILTI.

Some changes to GILTI may come sooner than 2025, however. In September 2020, Joe Biden’s presidential campaign released a set of proposals that included changes to GILTI.[55] He proposed increasing the minimum rate on GILTI, removing the QBAI deduction, and changing GILTI from a blended foreign income approach to a country-by-country calculation. Additionally, the Biden campaign called for a 28 percent corporate tax rate, another factor that will impact GILTI.

Separately, the high-tax exemptionA tax exemption excludes certain income, revenue, or even taxpayers from tax altogether. For example, nonprofits that fulfill certain requirements are granted tax-exempt status by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), preventing them from having to pay income tax. could also be a target for changes. Senators Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Sherrod Brown (D-OH) released legislation in February 2020 that intended to undo the high-tax exception regulatory work being done by Treasury.[56]

Both the changes already scheduled for 2025 and the changes proposed by the Biden campaign and Senate Democrats would increase taxes on foreign earnings of U.S. companies. Relative to the example from Table 2, which accounts for the current high-tax exception (Current Law in Table 3), the Biden campaign proposals would essentially double the tax burden on zero-tax subsidiaries. Removing the high-tax exemption would increase taxes just for companies with higher foreign tax burdens.

| Zero-Tax Foreign Subsidiary | Low-Tax Foreign Subsidiary | Average-Tax Foreign Subsidiary | High-Tax Foreign Subsidiary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foreign tax rate | 0% | 10% | 20% | 30% | |

| Current Law | Total Global Tax on Foreign Income | 10.0% | 14.2% | 20.0% | 30.0% |

| Scheduled Change in GILTI Deduction | Total Global Tax on Foreign Income | 12.5% | 14.5% | 20.0% | 30.0% |

| Remove High-tax Exception | Total Global Tax on Foreign Income | 10.0% | 14.2% | 24.2% | 34.2% |

| Biden Campaign Proposals | Total Global Tax on Foreign Income | 21.0% | 23.0% | 25.6% | 30.0% |

|

Note: All reform scenarios are relative to Current Law. The scheduled change in GILTI would shrink the GILTI deduction from 50 percent to 37.5 percent beginning after Dec. 31, 2025. The Biden campaign proposals include elimination of the QBAI deduction, shrinking the GILTI deduction from 50 percent to 25 percent, and a 28 percent U.S. corporate tax rate. Though the Biden campaign document does not specifically mention a 25 percent GILTI deduction, it does say that GILTI would be taxed at 21 percent. One way to achieve this under the current structure of GILTI would be a 25 percent deduction alongside a 28 percent corporate tax rate. Source: Author’s calculations based on a similar example provided in Michael J Caballero and Isaac Wood, “Restoring a ‘Not GILTI’ Verdict for High-Taxed Income,” Tax Notes, Oct. 8, 2018. |

|||||

Figure 5 shows how the Biden campaign proposals would increase the tax burden on the foreign income of a company with a subsidiary in a jurisdiction with a 10 percent corporate tax rate. Under current law (and as shown in Table 1) the total combined tax rate faced by that subsidiary’s foreign earnings is 14.2 percent. Shrinking the GILTI deduction from 50 percent to 25 percent would increase that burden by 2.8 percentage points, eliminating the QBAI deduction would add another 0.8 percentage points, and increasing the corporate tax rate to 28 percent would increase the burden by 5.25 percentage points. In sum, the tax burden would rise from 14.2 percentage to 23 percent.

Evaluating the Changes to GILTI

Each change illustrated above has the potential to put U.S. companies at a competitive disadvantage relative to their foreign competitors. GILTI is already a relatively unique policy on the international tax landscape and increasing tax burdens on foreign earnings by limiting the general GILTI deduction, QBAI, or removing the high-tax exception will put U.S. companies at a detriment when compared with their competition abroad.[57]

Aside from the direct impact on GILTI, the changes would also impact FDII, which was intended to improve incentives for businesses to locate their intangible assets in the U.S. A 28 percent corporate tax rate, as Biden has proposed, would increase the rate on FDII from 13.125 percent to 17.4 percent.[58] The rate on FDII would then be below that of GILTI. The difference could result in companies choosing to reshore intangible assets or encourage inversions to avoid extra U.S. tax liability.

The shift from a blended approach to having businesses calculate their liability on a country-by-country basis would exacerbate compliance costs. Businesses are not currently required to calculate tax liability at the country level. This would increase the salience of the tax on GILTI, levying a higher overall tax burden on low-tax income, while exacerbating existing compliance challenges. Some U.S. multinationals have subsidiaries in every country and jurisdiction on earth, and such a change would require them to calculate the tax liability of over 200 jurisdictions.

The coming changes should also be evaluated against the territorial principle introduced in the recent tax reform. If companies decide to locate intangible assets offshore in a low-tax jurisdiction and then license rights to their assets to U.S. customers, the U.S. tax base erodes. In theory, a minimum tax below the U.S. rate (even significantly below the average rate abroad) allows U.S. companies to expand and earn income overseas with limited exposure to additional U.S. taxes except in cases where they pay very little in foreign taxes.

However, the proposals outlined by the Biden campaign would increase the taxes on foreign earnings to the extent that the rates paid on foreign earnings would rise substantially relative to current law and be much closer to the average corporate rate in the developed world. Rather than being a minimum tax on a subset of foreign earnings, the Biden proposals would use a higher rate on a broader definition of GILTI to revert to a mostly worldwide tax system, despite the fact that most other countries have territorial rules.

Using an anti-base erosion policy designed for a territorial system to revert to worldwide taxation would make the U.S. tax system even less coherent than it is now.[59] Under the Biden campaign proposals, many companies would face worldwide taxation on their income that is taxed at less than 21 percent. Though the U.S. does not have a pure territorial system now, increasing the rate applicable to GILTI would significantly reduce the value of having territorial provisions by requiring many more U.S. multinationals to owe additional U.S. tax on GILTI.

Conclusion

Despite the recent tax reform, the rules for foreign earnings of U.S. companies are complicated and their impacts have yet to fully play out. As the global economy recovers from the pandemic-driven recession, businesses will need tax certainty as activity rebounds in domestic and foreign markets.

The 2017 tax law moved the U.S. system toward territoriality and dramatically reduced the corporate tax rate. The corporate tax rate reduction was, by itself, a serious measure to reduce profit shifting incentives as it brought the U.S. corporate tax rate closer to the average among developed countries. Lawmakers also adopted a minimum tax on a new definition of foreign income (GILTI) to further limit the tax benefits of profit shiftingProfit shifting is when multinational companies reduce their tax burden by moving the location of their profits from high-tax countries to low-tax jurisdictions and tax havens. . One major underlying problem with GILTI is its interaction with the expense allocation rules for the Foreign Tax Credit which can increase taxes paid on foreign earnings even if a company already pays high foreign taxes.

GILTI now stands on top of the pre-existing foreign tax credit rules and the high-tax exception provisions of Subpart F. Furthermore, GILTI is an outlier among the various anti-avoidance rules employed by our global competitors.

The Biden campaign and Senate Democrats identified changes to GILTI that would increase the taxes U.S. companies pay on their foreign earnings. Rather than tacking on changes to a system that is currently neither fully territorial nor worldwide, policymakers should evaluate the structure of the current system with a goal of it becoming more, not less, coherent.

Most developed countries have territorial tax policies and targeted anti-base erosion rules. The U.S. could follow in that example by removing expense allocation for foreign tax credits to ensure that GILTI is truly targeted to foreign earnings that face low levels of foreign taxes.

If, alternatively, policymakers choose to shift policy from territorial to worldwide taxation, GILTI is not well-suited to that endeavor.

Appendix

| Zero-Tax Foreign Subsidiary | Low-Tax Foreign Subsidiary | Average-Tax Foreign Subsidiary | High-Tax Foreign Subsidiary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foreign tax rate | 0% | 10% | 20% | 30% | |

| Current Law (including High-tax Exception) | Total Global Tax on Foreign Income | 10.0% | 14.2% | 20.0% | 30.0% |

| Remove QBAI | Total Global Tax on Foreign Income | 10.5% | 14.2% | 20.0% | 30.0% |

| Increase the Corporate Tax Rate from 21% to 28% | Total Global Tax on Foreign Income | 13.3% | 15.6% | 25.6% | 30.0% |

| Reduce the GILTI Deduction from 50% to 25% | Total Global Tax on Foreign Income | 15.0% | 17.0% | 20.0% | 30.0% |

| Combined Biden Campaign Proposals | Total Global Tax on Foreign Income | 21.0% | 23.0% | 25.6% | 30.0% |

|

Note: All reform scenarios are relative to current law. Though the Biden campaign document does not specifically mention a 25 percent GILTI deduction, it does say that GILTI would be taxed at 21 percent. One way to achieve this under the current structure of GILTI would be a 25 percent deduction alongside a 28 percent corporate tax rate. Source: Author’s calculations based on a similar example provided in Michael J Caballero and Isaac Wood, “Restoring a ‘Not GILTI’ Verdict for High-Taxed Income,” Tax Notes, Oct. 8, 2018. |

|||||

[1] Ronald B. Davies and James R. Markusen, “The Structure of Multinational Firms’ International Activities,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 26827, Mar. 9, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3386/w26827.

[2] This is partially because U.S. equities make up a large share of global capital markets and because of home bias in which investors are more likely to own stocks from companies based in their country than in foreign countries. See Kenneth R. French and James M. Poterba, “Investor Diversification and International Equity Markets,” The American Economic Review 81:2 (May 1991), https://www.jstor.org/stable/2006858.

[3] Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Activities of U.S. Multinational Enterprises, 2018,” Aug.21, 2020, https://www.bea.gov/news/2020/activities-us-multinational-enterprises-2018.

[4] Evidence on this can be found in Mihir A. Desai, C. Fritz Foley, and James R. Hines Jr., “Foreign Direct Investment and Domestic Economic Activity” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 11717, Oct. 24, 2005, https://doi.org/10.3386/w11717, and Mihir A. Desai, C. Fritz Foley, and James R. Hines Jr., “Foreign Direct Investment and the Domestic Capital Stock,” American Economic Review 95:2 (May 2005), https://doi.org/10.1257/000282805774670185.

[5] Chiara Criscuolo, Jonathan E. Haskel, and Matthew J. Slaughter, “Global Engagement and the Innovation Activities of Firms,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 11479, June 2005, https://doi.org/10.3386/w11479.

[6] Mihir A. Desai, C. Fritz Foley, and James R. Hines, “Economic Effects of Regional Tax Havens” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 10806, Oct. 4, 2004, https://doi.org/10.3386/w10806.

[7] Thirty-one OECD countries exempt at least 95 percent of foreign-earned dividends from taxation while 26 exempt at least 95 percent of foreign-earned capital gains. Ireland has a unique approach where 100 percent of foreign-earned capital gains are exempt, but there is no exemption for foreign-earned dividends. The new U.S. system exempts 100 percent of qualifying foreign dividends but does not exempt foreign-earned capital gains. The five countries without territorial treatment include Chile, Colombia, the Republic of Korea, Israel, and Mexico. See Daniel Bunn and Elke Asen, International Tax Competitiveness Index 2020, Tax Foundation, Oct. 14, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/publications/international-tax-competitiveness-index/.

[8] Taxes are not the only defining factor for competitiveness and business location decisions. Local labor market talent, natural resources, infrastructure, and numerous other factors can also influence both where a firm decides to invest and whether that firm’s country of residence gives it a competitive advantage in global markets.

[9] This measure is broader than the capital stock measure of intangible assets and includes brand value and goodwill. See Ocean Tomo, “Intangible Asset Market Value Study,” Dec. 16, 2020, https://www.oceantomo.com/intangible-asset-market-value-study/.

[10] Michael J. Mauboussin and Dan Callahan, “One Job: Expectations and the Role of Intangible Investments” Morgan Stanley Investment Management, Sept.15, 2020, https://www.morganstanley.com/im/publication/insights/articles/articles_onejob.pdf?1600268687963.

[11] Recent rules changes have made this more challenging for businesses. Businesses must have more substantive activities in a jurisdiction to enjoy tax preferences like patent boxes now. For more information on patent boxA patent box—also referred to as intellectual property (IP) regime—taxes business income earned from IP at a rate below the statutory corporate income tax rate, aiming to encourage local research and development. Many patent boxes around the world have undergone substantial reforms due to profit shifting concerns. regimes and these rules, see Elke Asen and Daniel Bunn, “Patent Box Regimes in Europe,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 26, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/patent-box-regimes-in-europe-2020/. However, it likely remains true that the location of intellectual property ownership is sensitive to tax rates, as found in Rachel Griffith, Helen Miller, and Martin O’Connell, “Ownership of Intellectual Property and Corporate Taxation,” Journal of Public Economics 112 (April 2014, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2014.01.009.

[12] Elke Asen, “Corporate Tax Rates around the World” Tax Foundation, Dec. 9, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/corporate-tax-rates-around-the-world-2020/.

[13] For a review of anti-base erosion policies adopted by the U.S. and other countries, see Daniel Bunn, Kyle Pomerleau, and Sebastian Dueñas, “Anti-Base Erosion Provisions, Territorial Tax Systems in OECD Countries,” Tax Foundation, May 2, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/anti-base-erosion-provisions-territorial-tax-systems-oecd-countries/.

[14] For more background on tax planning and policies to address it, see Daniel Bunn, “Profit Shifting: Evaluating the Evidence and Policies to Address It,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 31, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/profit-shifting-evaluating-evidence-policies/.

[15] Kyle Pomerleau, “A Hybrid Approach: The Treatment of Foreign Profits under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Tax Foundation, May 3, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/treatment-foreign-profits-tax-cuts-jobs-act/.

[16] Accounting for average state-level corporate taxes, the combined federal and state corporate tax rate was 38.9 percent. See Elke Asen, “Corporate Tax Rates around the World.”

[17] See the next section for a discussion of foreign tax credit calculations.

[18] For more details on repatriation see the section “Impacts of the Reforms” below.

[19] Michael J. Graetz and Paul W. Oosterhuis, “Structuring an Exemption System for Foreign Income of U.S. Corporations,” National Tax Journal 54:4 (December 2001), https://doi.org/10.17310/ntj.2001.4.06.

[20] Ibid.

[21] For more information on such incentives, and particularly tax inversions, see Cathy Hwang, “The New Corporate Migration,” Brooklyn Law Review 80:3 (2015), https://www-cdn.law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Inversions-final.pdf, and Kimberly Clausing, “Corporate Inversions,” Tax Policy Center, Aug. 20, 2014, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/22866/413207-Corporate-Inversions.PDF.

[22] David Zion, Ravi Gomatam, and Ron Graziano, “Parking A-Lot Overseas,” Credit Suisse, Mar. 17, 2015, https://research-doc.credit-suisse.com/docView?language=ENG&format=PDF&source_id=em&document_id=1045617491&serialid=jHde13PmaivwZHRANjglDIKxoEiA4WVARdLQREk1A7g%3d

[23] Jessica McKeon, “Indefinitely Reinvested Foreign Earnings Still Climbing,” Audit Analytics, Aug. 14, 2017, https://www.auditanalytics.com/blog/indefinitely-reinvested-foreign-earnings-still-climbing/.

[24] Zachary Mider, “Tax Inversion,” Bloomberg, Mar. 2, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/quicktake/tax-inversion.

[25] The totality of international tax reforms in the TCJA were projected to increase federal revenues by $324 billion over the 2018-2027 period. See The Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Conference Agreement for H.R. 1, the ‘Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’,” Dec. 18, 2017, https://www.jct.gov/publications/2017/jcx-67-17/.

[26] As shown in Figure 1, in 2017 the U.S. combined corporate rate was 12 points above the non-U.S. OECD average (weighted by GDP) and 15 points above the non-U.S. OECD simple average. In 2020, the U.S. combined corporate rate was 0.8 points below the non-U.S. OECD average (weighted by GDP) and 2.3 points above the non-U.S. OECD simple average. See Elke Asen, “Corporate Tax Rates Around the World.”

[27] However, the existence of tax jurisdictions with very low or no corporate taxes means that a corporate tax rate reduction in a high-tax country will not simply mean multinationals will completely end tax planning. The incentives may still be lessened, though. See Tim Dowd, Paul Landefeld, and Anne Moore, “Profit Shifting of U.S. Multinationals,” Journal of Public Economics 148 (April 2017), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2017.02.005.

[28] The tax benefit for FDII is set to be reduced after 2025, so the effective tax rate would rise to 16.4 percent under current law. For a description of FDII’s mechanics, see Kyle Pomerleau, “A Hybrid Approach: The Treatment of Foreign Profits under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.”

[29] Elke Asen and Daniel Bunn, “Patent Box Regimes in Europe.”

[30] The BEAT rate is scheduled to rise to 12.5 percent beginning in 2026. The $500 million in revenues is measured as a three-year moving average. The BEAT rate of 10 percent applies to a U.S. company’s taxable income plus the value of base erosion payments minus liability for normal corporate tax. For an example of a BEAT calculation, see Kyle Pomerleau, “A Hybrid Approach: The Treatment of Foreign Profits under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.”

[31] Biden-Harris Campaign, “The Biden-Harris Plan to Fight for Workers by Delivering on Buy America and Make It in America,” September 2020, https://joebiden.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Buy-America-fact-sheet.pdf.

[32] These policies are generally referred to as Controlled Foreign Corporation (CFC) rules. For more about how they work, see Daniel Bunn, Kyle Pomerleau, and Sebastian Dueñas, “Anti-Base Erosion Provisions, Territorial Tax Systems in OECD Countries.”

[33] Earnings of French foreign subsidiaries are also exempt if they are not from an artificial arrangement, or if the foreign entity carries out trading or manufacturing activity. The French corporate tax rate (including the applicable surtax) is 28.4 percent.

[34] The combined German corporate tax rate is 29.9 percent.

[35] Income that is already subject to U.S. taxes, like Subpart F income, is excluded from the GILTI calculation.

[36] Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, “Illustration of Effective tax rates on FDII and GILTI.”

[37] Aaron Junge, Karl Edward Russo, and Peter Merrill, “Design Choices for Unilateral and Multilateral Foreign Minimum Taxes,” Tax Notes International, Sept. 2, 2019, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-international/international-taxation/design-choices-unilateral-and-multilateral-foreign-minimum-taxes/2019/09/02/29wp3?highlight=restoring%20a%20not%20GILTI%20verdict.

[38] Greg Pudenz, Jamison Sites, and Ramon Camacho, “GITLI: A New Age of Global Tax Planning,” TheTaxAdviser.com, Apr. 1, 2019, https://www.thetaxadviser.com/issues/2019/apr/gilti-new-age-global-tax-planning.html.

[39] In reality, a company will have multiple subsidiaries taxed at various rates and the income will be blended in calculating GILTI. This means high-tax income blended with low-tax income will raise the average foreign tax rate and limit GILTI liability. At the same time, high-tax income will be more likely to face the burden of expense allocation and the 80 percent limit on foreign tax credits.

[40] In the example, this latter limit is simplified by multiplying Deemed Foreign Source Income by the U.S. corporate tax rate of 21 percent.

[41] Richard Rubin, “New Tax on Overseas Earnings Hits Unintended Targets,” The Wall Street Journal, Mar. 26, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/new-tax-on-overseas-earnings-hits-unintended-targets-1522056600.

[42] Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, “Illustration of Effective tax rates on FDII and GILTI.”

[43] Federal Register, “Guidance Under Sections 951A and 954 Regarding Income Subject to a High Rate of Foreign Tax,” July 23, 2020, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/07/23/2020-15351/guidance-under-sections-951a-and-954-regarding-income-subject-to-a-high-rate-of-foreign-tax.

[44] Mindy Herzfeld, “The GILTI High-Tax Exception: Who Benefits?” Tax Notes, Aug. 24, 2020, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-international/tax-cuts-and-jobs-act/gilti-high-tax-exception-who-benefits/2020/08/24/2cvm4.

[45] Ninety percent of the 21 percent corporate tax rate is 18.9 percent.

[46] For more on this general point, see Michael J. Graetz and Paul W. Oosterhuis, “Structuring an Exemption System for Foreign Income of U.S. Corporations,” 771–86; and Daniel Shaviro, “Does More Sophisticated Mean Better? A Critique of Alternative Approaches to Sourcing the Interest Expense of American Multinationals,” SSRN Scholarly Paper Social Science Research Network, December 2000, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.255579.

[47] U.S. House of Representatives Ways and Means Committee, “Ways and Means Discussion Draft,” Oct. 26, 2011, /wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Tax-Foundation-Comments-on-the-Wyden-Warner-Brown-Discussion-Draft.pdf.

[48] Two other considerations would change the results, but not influence the overall lesson that changing investment behavior for the sake of QBAI would provide little reward. First, a new investment overseas is likely to mean new foreign profits. It is possible the profits would be minimal, but they are not considered in the example. Second, if the new foreign investment comes at the expense of investment in the U.S., the company would likely be losing out on investment deductions against U.S. taxes, further limiting the benefit of increasing QBAI to offset GILTI liability.

[49] T.J. Atwood et al., “The Impact of U.S. Tax Reform on U.S. Firm Acquisitions of Domestic and Foreign Targets,” SSRN Scholarly Paper Social Science Research Network, May 14, 2020, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3600978.

[50] Kartikeya Singh and Aparna Mathur, “The Impact of GILTI and FDII on the Investment Location Choice of U.S. Multinationals,” SSRN Scholarly Paper Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, May 17, 2018, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3180144.

[51] T. J. Atwood et al., “The Impact of U.S. Tax Reform on U.S. Firm Acquisitions of Domestic and Foreign Targets.”

[52] Scott Dyreng et al., “The Effect of U.S. Tax Reform on the Tax Burdens of U.S. Domestic and Multinational Corporations,” SSRN Scholarly Paper Social Science Research Network, June 5, 2020, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3620102.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Kimberly Clausing, “Profit Shifting Before and After the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” National Tax Journal 73:4 (2020), http://dx.doi.org/10.17310/ntj.2020.4.14. Clausing is currently the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Tax Analysis, Office of Tax Policy at the U.S. Treasury Department.

[55] Biden-Harris Campaign, “The Biden-Harris Plan to Fight for Workers by Delivering on Buy America and Make It in America.”

[56] Sen. Ron Wyden, “S.3280 – 116th Congress (2019-2020): Blocking New Corporate Tax Giveaways Act,” Feb. 12, 2020, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/3280.

[57] It is possible that there will be a global agreement on minimum taxes for business in the future. If that comes to fruition, then the relative disadvantage for U.S. companies due to GILTI would only be reflected in any remaining differences between GILTI and a global minimum tax.

[58] Following the smaller deduction for FDII at the end of 2025, the rate on FDII in the context of a 28 percent corporate rate would be 21.875 percent. For context, the tax rate on patent income in many other jurisdictions is below 15 percent and many in Europe are below 10 percent. See Elke Asen and Daniel Bunn, “Patent Box Regimes in Europe.”

[59] For another look at the Biden campaign approach on corporate taxation, see Martin A. Sullivan, “Biden’s Incoherent Corporate Tax Policy,” Tax Notes, Jan. 4, 2021, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-today-federal/tax-policy/bidens-incoherent-corporate-tax-policy/2021/01/04/2dc59.

Residual U.S. Tax (G – L = M)

$8.40

This is the additional tax the U.S. parent company pays on top of the foreign taxes already paid by the subsidiary.

Share this article