Key Findings

- The taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. code contains several provisions which vary based on family composition and are designed for purposes such as offsetting the costs of having children or encouraging lower-income individuals to join the labor force.

- Currently, family status affects at least six tax provisions: the child tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. , the child and dependent care tax credit and exclusion for employer-sponsored child and dependent care benefits, the earned income tax credit, filing status, the standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. It was nearly doubled for all classes of filers by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) as an incentive for taxpayers not to itemize deductions when filing their federal income taxes. , and tax rates and brackets.

- The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act reformed three of the primary family provisions, by consolidating them into two expanded provisions, which simplified some parts of the individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. code.

- The remaining provisions are still in need of reform. Many of the credits have different, and complex, qualification requirements, which leads to taxpayer confusion and problems with administrability.

- Provisions that are related to work contain family status differentials, providing greater work incentives to workers with children than to workers without children, with no clear policy rationale.

- Other family provisions contribute to marriage penalties or bonuses, resulting in different tax liability for couples than if they both were single.

- The nonneutral treatment of different taxpayers, differences in qualifying requirements, and the overlap between some of the work and child benefits, present an opportunity for reforms that would simplify the process for taxpayers and better focus the intended incentives.

Introduction

The benefits of many provisions of the individual income tax code vary depending on a taxpayer’s family status. Similarly, tax rates and brackets vary by whether taxpayers are single, married, or filing under a different status. Qualifying requirements vary across these provisions, and some combine child-related benefits with work-related benefits. While these policies are designed to help taxpayers, they add unnecessary complexity to the tax code and thus are well suited for reform.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) made important changes to three of the primary family provisions in the tax code: the standard deduction, the personal exemption, and the child tax credit. However, further reforms could consolidate the various family-related credits into streamlined credits for children and for work and provide certainty to taxpayers by making the changes of the TCJA permanent.

This paper reviews six family-related tax provisions under current law, including how the TCJA reformed three of the primary family provisions, and examines the need for further reform.

Family Provisions under Current Law

Prior to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the tax code contained three primary provisions which reduced household income taxes dependent on household size. These were the standard deduction, the personal exemption, and the child tax credit. Under the TCJA, these three provisions were consolidated into two: the personal exemption was eliminated in favor of an expanded standard deduction and child tax credit.[1]

The new tax law increases the standard deduction to $12,000 for single filers, $18,000 for heads of household, and $24,000 for joint filers in 2018 (compared to $6,500, $9,550, and $13,000 respectively under prior law), and it eliminates the personal exemption, which had previously allowed households to reduce their taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. by $4,150 for each filer and dependent.[2] It also expanded the child tax credit from $1,000 to $2,000, making up to $1,400 refundable, while increasing the income phaseout from $110,000 to $400,000 for married couples.

These three changes are nearly revenue neutral. Over the next eight years, the expanded standard deduction will reduce federal revenue by $690 billion, the elimination of the personal exemption will increase revenue by $1.16 trillion, and the expanded child tax credit will reduce revenue by $474 billion.[3] In total, the three changes reduce federal revenue by just $4.2 billion between 2018 and 2025, after which the provisions expire.

Though these changes have a negligible impact on federal revenue, they have important implications for the structure of the individual income tax. These changes simplify the tax code for many Americans.[4] By making the standard deduction larger, the value of itemized deductions is lessened. Nearly 29 million more filers will be better off taking the expanded standard deduction instead of itemizing their deductions.[5]

While the TCJA made important progress in simplifying the individual income tax, the individual code remains unnecessarily complex. Many of the credits which relate to the cost of raising children have different requirements for qualifying children. Provisions that are related to work also contain elements that increase benefits in relation to family size, providing greater work incentives to workers with children than to workers without children.

Currently, family status affects at least six tax provisions: the child tax credit, the child and dependent care tax credit and exclusion for employer-sponsored child and dependent care benefits, the earned income tax credit, filing status, the standard deduction, and tax rates and brackets.

Child Tax Credit

The child tax credit provides a tax credit per child under the age of 17 to taxpayers. If the credit exceeds a taxpayer’s liability, they may receive a portion of the credit as a refund. Eligibility for the credit depends on seven requirements, including the age of the child and the income level of the household.[6]

Prior to the TCJA, the child tax credit was a credit which offset tax liability. A separate credit, the Additional Child Tax Credit, allowed for a portion of the child tax credit to be refundable if it exceeded tax liability. However, under the TCJA there is not an Additional Child Tax Credit separate from the child tax credit; rather, there is one credit that is refundable, subject to certain requirements.[7]

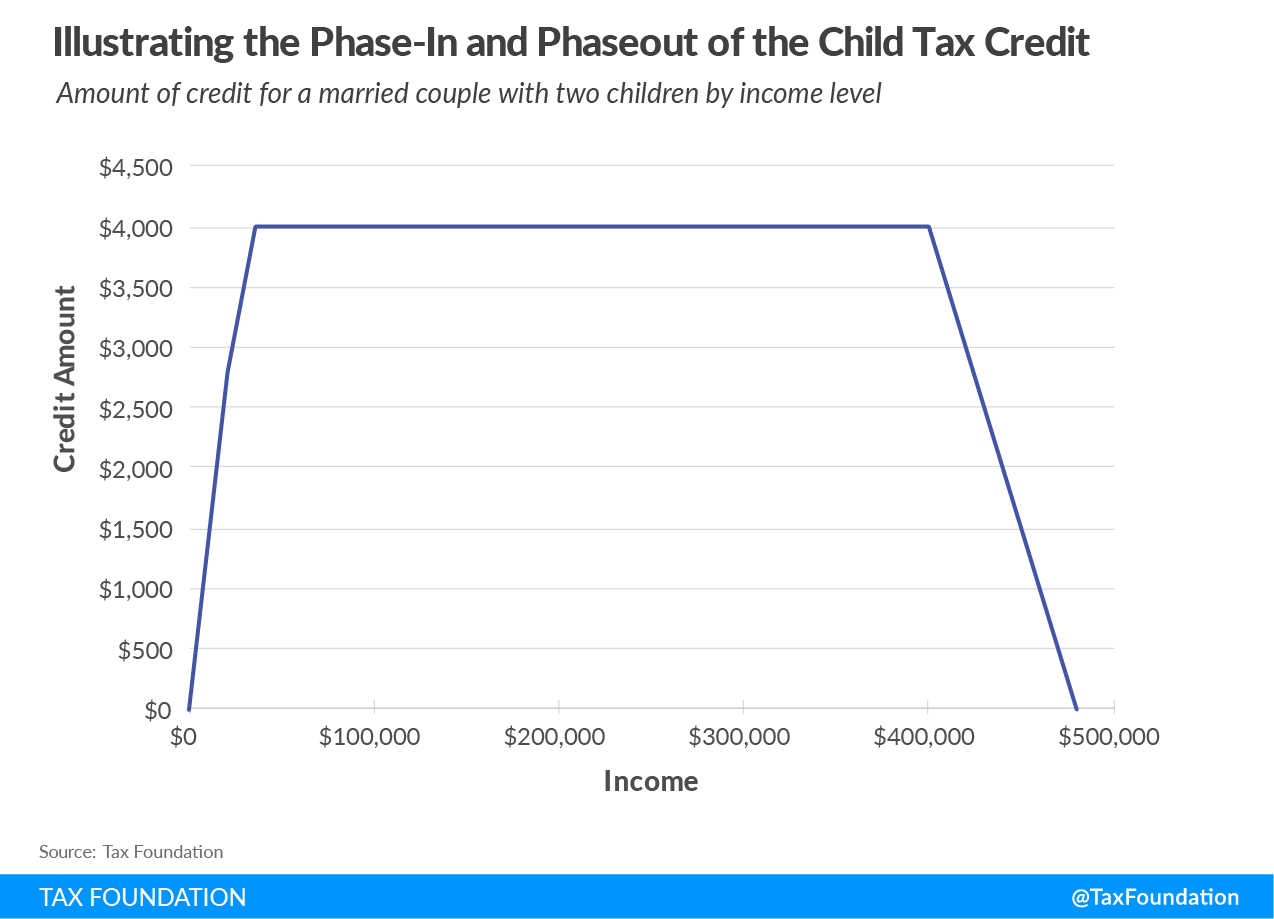

The TCJA doubled the maximum child tax credit from $1,000 to $2,000 and makes up to $1,400 of the credit refundable.[8] The only portion of the child tax credit that is indexed to inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. is the refundability limit. Under current law, if the tax credit exceeds tax liability, taxpayers generally use an earned income formula to determine refundability: 15 percent of income above $2,500, up to the full refundability amount. For example, a family with $5,000 in earned income would be eligible for a refund of $375.[9]

The credit phases out at a 5 percent rate for married filers making above $400,000 and all other filers making above $200,000. For example, the maximum credit per child a single filer making $220,000 could receive would be $1,000 instead of the maximum credit of $2,000.[10] These new thresholds are set by the TCJA. Under old law, the credits phased out at much lower income levels.[11]

The new tax law also expanded the child tax credit by adding a nonrefundable $500 credit for each dependent who is not a qualifying child under age 17.[12] This new credit, referred to as a “family credit,” is designed to compensate for the eliminated personal exemption[13] and is subject to the same phaseout as the child tax credit.

These expansions of the child tax credit are currently scheduled to expire after 2025.

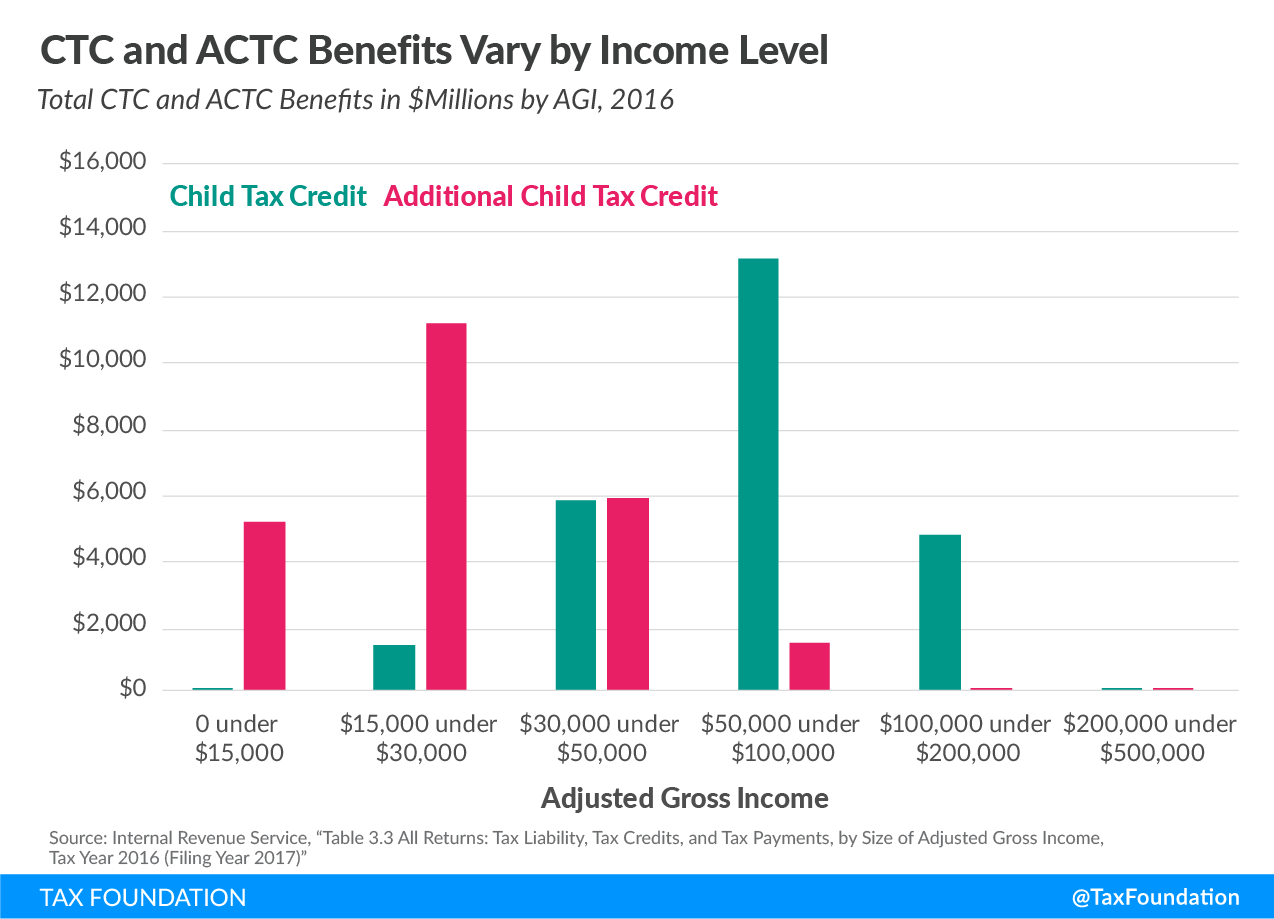

In tax year 2016, pre-TCJA, more than 22 million households claimed the child tax credit for a total of $26.8 billion, while 18.9 million claimed the Additional Child Tax Credit for benefits of $25.4 billion.[14] (Note that under current law, there is just one refundable child tax credit.) The benefits of the child tax credit peak at households making between $50,000 and $100,000, while the benefits of the Additional Child Tax Credit peak at households making between $15,000 and $30,000. Because of the income phaseout range prior to the TCJA, a relatively small number of households in the $200,000 to $500,000 AGI range benefited from either of the credits.

The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that in 2018, the child tax credit will reduce federal revenues by $103.8 billion,[15] which is significantly larger than the pre-TCJA estimate of $54.2 billion for 2018.[16] This difference reflects the doubling of the maximum child tax credit, the increase in the refundability amount, the credit for other dependents, and the expanded income thresholds. These changes will impact the distribution of the child tax credit.

Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit and Exclusion for Employer-Sponsored Child and Dependent Care Benefits

The tax code also allows for a provision to help offset some of the costs of child or dependent care. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act did not make changes to this credit.

Eligibility for this credit depends on meeting seven tests, outlined in Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Publication 503.[17] Qualifying individuals are children under the age of 13 for the entire year or the taxpayer’s spouse or dependent who is incapable of caring for himself or herself.[18] The taxpayer and spouse, for households filing jointly, must both meet earned income tests, and the care expenses must be related to working or looking for work. Additionally, married taxpayers must file jointly to be eligible for the credit.

Taxpayers calculate their credit by multiplying qualifying expenses by a credit rate. The credit rate varies from 35 percent to 20 percent depending on the taxpayer’s adjusted gross income (AGI). Qualifying expenses are limited to $3,000 for one qualifying individual or $6,000 for two or more qualifying individuals, and the credit is not refundable.

The credit rate begins at 35 percent for taxpayers with adjusted gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total pre-tax earnings from wages, tips, investments, interest, and other forms of income and is also referred to as “gross pay.” For businesses, gross income is total revenue minus cost of goods sold and is also known as “gross profit” or “gross margin.” (AGI) between $0 and $15,000 and gradually phases down to 20 percent for taxpayers with AGI of $43,000 and above. Table 2 illustrates how income levels, the credit rate, and the maximum allowable expenses interact to determine the maximum credit taxpayers may claim; credits for one child range from $600 to $1,050 and for two or more children, $1,200 to $2,100. Note that the income thresholds are not adjusted for inflation.

|

Source: Internal Revenue Service, “Publication 503 (2017), Child and Dependent Care Expenses” |

|||||

| Maximum Statutory Credit Amount | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGI | Credit Rate | One Qualifying Individual (maximum expenses of $3,000) | Two or More Qualifying Individuals (maximum expenses of $6,000) | ||

| $0 under $15,000 | 35% | $1,050 | $2,100 | ||

| $15,000 under $17,000 | 34% | $1,020 | $2,040 | ||

| $17,000 under $19,000 | 33% | $990 | $1,980 | ||

| $19,000 under $21,000 | 32% | $960 | $1,920 | ||

| $21,000 under $23,000 | 31% | $930 | $1,860 | ||

| $23,000 under $25,000 | 30% | $900 | $1,800 | ||

| $25,000 under $27,000 | 29% | $870 | $1,740 | ||

| $27,000 under $29,000 | 28% | $840 | $1,680 | ||

| $29,000 under $31,000 | 27% | $810 | $1,620 | ||

| $31,000 under $33,000 | 26% | $780 | $1,560 | ||

| $33,000 under $35,000 | 25% | $750 | $1,500 | ||

| $35,000 under $37,000 | 24% | $720 | $1,440 | ||

| $37,000 under $39,000 | 23% | $690 | $1,380 | ||

| $39,000 under $41,000 | 22% | $660 | $1,320 | ||

| $41,000 under $43,000 | 21% | $630 | $1,260 | ||

| $43,000 and above | 20% | $600 | $1,200 | ||

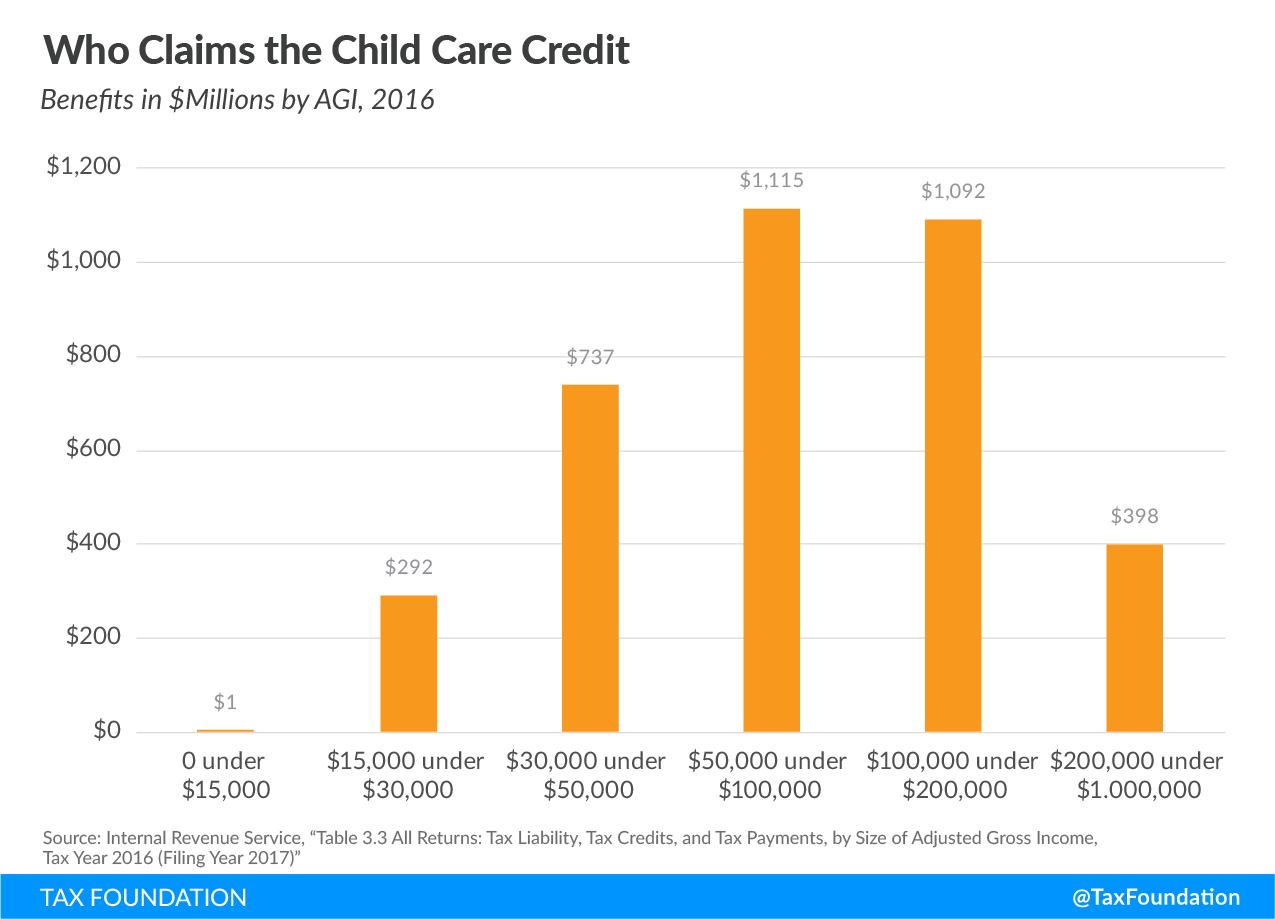

In tax year 2016, nearly 6.5 million households claimed the child care credit for total benefits of $3.6 billion. Like the child tax credit, the largest share of the child care credit benefits go to taxpayers making between $50,000 and $100,000. However, the largest average credit per return is claimed by taxpayers in the $30,000 to $50,000 income group, at $595.06 per return.[19]

In addition to the credit for care expenses, taxpayers whose employers provide dependent care benefits under a qualified plan may be able to exclude those benefits from their income. If a plan qualifies, the maximum a taxpayer can exclude is the smallest of four limits: the total benefit, the total amount of qualified expenses, the taxpayer or spouse’s earned income, or $5,000. A common example of a qualifying employer-sponsored plan is a Flexible Spending Account used to pay for qualifying care.[20]

The exclusion for employer-provided benefits does interact with the credit for care expenses outlined above. Every dollar of exclusion reduces the maximum amount of qualifying expenses for the credit, dollar for dollar. For example, if a household has one qualifying person they would normally be able to use a maximum of $3,000 in expenses to calculate their credit. However, if this household also receives dependent care benefits from work, and excludes, for example, $1,000 of employer benefits from their income, this would directly reduce their dollar limit for the credit by $1,000 to $2,000; see table 2.

|

Source: Author’s calculations |

|

|

Maximum Credit Allowed |

$3,000 |

|

Less Exclusion of Employer Benefits |

-$1,000 |

|

New Credit Limit |

$2,000 |

In tax year 2016, 1.2 million households excluded $4.3 billion worth of child care benefits from their taxable income.[21] Note that the value of an exclusion depends on what tax bracket the household falls under. For example, a $1,000 exclusion taken by a household in the 12 percent tax bracket would result in $120 of tax savings, but in the 22 percent bracket, the same $1,000 exclusion would result in $220 of tax savings, whereas the value of a credit is the same across income levels. The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that together, the tax credit for child and dependent care and the exclusion for employer-provided benefits will reduce federal revenues by $4.6 billion in 2018.[22]

Earned Income Tax Credit

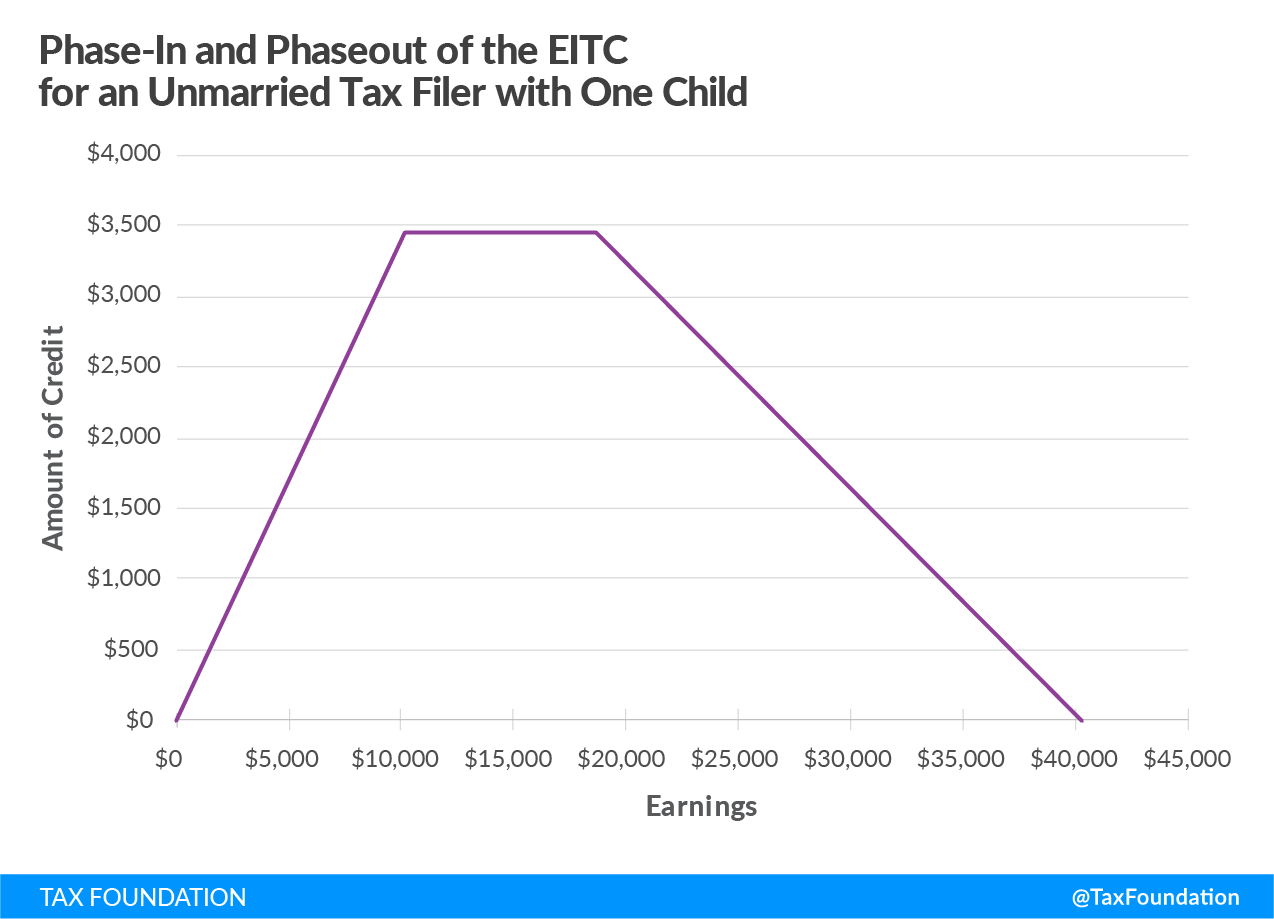

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) provides a credit that helps offset income taxes for relatively low-income taxpayers and is refundable if the credit exceeds tax liability. It is intended to supplement other social and welfare programs while encouraging recipients to work.[23]

The EITC equals a fixed percentage (the credit rate) of earned income up to the maximum credit amount. The maximum credit amount varies greatly depending on the number of children in the household and the taxpayer’s marital status.

The EITC remains at the maximum between the earned income threshold and the phaseout threshold, at which point the credit begins phasing down at a set rate as income exceeds the phaseout threshold. For example, if a single taxpayer with no children earned $9,000 in one year, their maximum credit would be reduced by 7.65 percent of their income over the phaseout threshold, resulting in a credit of around $480 instead of the $519 maximum.[24]

The table below illustrates this variation. For example, the maximum credit amount that childless workers receive is $519, while the maximum for workers with one child is more than six times larger, at $3,461. This creates a large family-status differential.

|

Source: Gene Falk and Margot L. Crandall-Hollick, “The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC): An Overview.” |

||||

| Filing status | No children | One child | Two children | Three or more children |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Single or head of household |

||||

|

Credit Rate |

7.65% | 34% | 40% | 45% |

|

Earned Income Threshold |

$6,780 | $10,180 | $14,290 | $14,290 |

|

Maximum Credit |

$519 | $3,461 | $5,716 | $6,431 |

|

Phaseout Threshold |

$8,490 | $18,660 | $18,660 | $18,660 |

|

Phaseout Rate |

7.65% | 15.98% | 21.06% | 21.06% |

|

Income Where Credit Equals $0 |

$15,270 | $40,320 | $45,802 | $49,194 |

|

Married filing jointly |

||||

|

Credit Rate |

7.65% | 34% | 40% | 45% |

|

Earned Income Threshold |

$6,780 | $10,180 | $14,290 | $14,290 |

|

Maximum Credit |

$519 | $3,461 | $5,716 | $6,431 |

|

Phaseout Threshold |

$14,710 | $24,350 | $24,350 | $24,350 |

|

Phaseout Rate |

7.65% | 15.98% | 21.06% | 21.06% |

|

Income Where Credit Equals $0 |

$20,950 | $46,010 | $51,492 | $54,884 |

The EITC can reduce a taxpayer’s tax liability, issued as a cash payment if the taxpayer has no liability, or a combination of both. Most households receive the EITC as a refund. In tax year 2016, 27.3 million tax returns claimed the EITC for a total of $66.7 billion, and of that amount $57.1 billion was refunded.[25]

Eligibility requirements for this credit are highly complex and depend on several factors, which leads to confusion and contributes to improper payments. Taxpayers must meet at least 20 requirements,[26] including: residency; earned income limits; earning less than a certain amount of investment income; the tax filer’s children must meet residency, age, and relationship requirements; childless workers must be between the age of 25 and 64; and Social Security numbers must be provided for the taxpayer, spouse, and any children for whom the credit is claimed.[27]

The Government Accountability Office estimated that in fiscal year 2017, more than $16 billion of the program’s $67.9 billion in outlays, or nearly 25 percent, were considered improper payments.[28] The Treasury Department has identified several factors which lead to improper payments, including complexity of the law, structure of the credit, confusion and turnover among eligible claimants, unscrupulous tax return preparers, and fraud.[29] However, none of the six factors are considered the primary driver of improper payments.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act did not directly make any reforms to the EITC. However, the new law does have an impact on the EITC through its changing of the measure used to index parameters to inflation, from the consumer price index for urban consumers (CPI-U) to chained CPI-U. Because chained CPI-U tends to grow more slowly than CPI-U, the monetary parameters of the EITC will increase at a slower pace.[30] This will impact the maximum credit amounts as well as the earned income and the phaseout limits.[31]

Other Family-Related Provisions

At least three other tax provisions also vary with household composition: filing status, the standard deduction, and tax rates and brackets.

Generally, taxpayers may file as single, married filing jointly, married filing separately, or head of household.[32] This affects eligibility for and the size of certain credits, the size of the standard deduction, and which tax rates and tax brackets income falls under; see Table 4.

| For Unmarried Individuals | For Married Individuals Filing Joint Returns | For Heads of Households | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2018 Standard Deduction |

$12,000 | $24,000 | $18,0000 |

| Rate |

Taxable Income Over |

||

| 10% | $0t | $0 | $0 |

| 12% | $9,525 | $19,050 | $13,600 |

| 22% | $38,700 | $77,400 | $51,800 |

| 24% | $82,500 | $165,000 | $82,500 |

| 32% | $157,500 | $315,000 | $157,500 |

| 35% | $200,000 | $400,000 | $200,000 |

| 37% | $500,000 | $600,000 | $500,000 |

An unintended consequence of these provisions is that they create marriage penalties or marriage bonuses, meaning that the combined income tax liability of a married couple may be higher or lower than it would have been if they remained single.[33]

For example, married taxpayers with no children may face marriage bonuses of up to 8 percent of the couple’s income or marriage penalties of up to 4 percent.[34] With one child, marriage bonuses can be as large as 21 percent of a couple’s income, and penalties can be as large as 8 percent of a couple’s income.[35]

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act reduced marriage penalties and bonuses across many tax bracketsA tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. , as all tax brackets for married filers are exactly double those for single filers, except for the top 37 percent marginal rate. Thus, marriage penalties are generally only felt at high income levels. However, for low-income individuals, marriage can push qualifying income for the EITC further into the phaseout range, thus resulting in a marriage penaltyA marriage penalty is when a household’s overall tax bill increases due to a couple marrying and filing taxes jointly. A marriage penalty typically occurs when two individuals with similar incomes marry; this is true for both high- and low-income couples. due to interaction with the credit. However, completely eliminating marriage penalties and bonuses would require a drastic overhaul of the U.S. income tax system.[36]

One Option for Further Reform

Recent reforms made some progress in simplifying the individual income tax by streamlining the three primary family provisions under the old tax code. However, as discussed above, several family and work-related provisions remain, and they are complex, confusing, and in some cases lead to problems with administrability. As such, these provisions would benefit from further reform efforts.

A Congressional Research Service report which reviewed the child tax credit under current law noted the following:[37]

The age and citizenship requirements for a qualifying child for the child tax credit differ from the definition of qualifying child used for other tax benefits and can cause confusion among taxpayers. For example, a taxpayer’s 18-year-old child may meet all the requirements for a qualifying child for the EITC but will be too old to be eligible for the child tax credit.

|

Source: Congressional Research Service |

||

| Age | Phaseouts | |

|---|---|---|

|

Child Tax Credit |

Under the age of 17 for the entire year |

Begins phasing down at $200,000 for single households, $400,000 for married households |

|

Child and Dependent Care Credit |

Under the age of 13 for the entire year or the taxpayer’s spouse or dependent who is incapable of caring for himself or herself |

Credit phases down between $15,000 and $43,000 but not to zero |

|

Earned Income Tax Credit |

Eligible Children: Under the age of 19 (or under the age of 24 if a full-time student) Taxpayers without eligible children must be between the age of 25 and 64 |

Begins phasing down from $8,490 to $24,350 depending on number of qualifying children and marital status Credit equals $0 when incomes reach $15,270 to $54,884 depending on number of qualifying children and marital status |

The family differential of the EITC, as well as differences in qualifying requirements across the credits, could be simplified and streamlined to better target benefits and incentives. Policy proposals such as consolidating the child-related provisions into one credit, and work-related provisions into another credit, would address these issues.

For example, in the Taxpayer Advocate Service 2008 Annual Report to Congress, one of the legislative recommendations outlined a proposal to simplify the family status provisions:[38]

Consolidate the numerous family status provisions into two. One provision (the Family Credit) would reflect the costs of maintaining a household and raising a family. It would incorporate all current family status provisions that are based on the specific make-up of the family unit and its corresponding ability to pay taxes. The second provision (which could be called the “Worker Credit” or could continue to be called the EITC) would provide an incentive and subsidy for low income individuals to work.

Under this proposal, all the differences in tax liability conferred by family-status provisions, such as the child tax credit, the head of household filing status, the family-size differential of the EITC, and, under prior law, the personal exemption, would be consolidated into one Family Credit. This would allow the EITC to focus its benefits solely on incentivizing work for lower-income households without regard to family size.

In addition to the need to simplify the provisions under current law, taxpayers need certainty in the changes made by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which are currently scheduled to expire after 2025. Rather than waiting until the last minute to decide which provisions to make permanent and which to let expire, lawmakers should consider the costs and benefits of permanence well before the end of 2025, keeping in mind that reforms like those made to the three family provisions are nearly revenue neutral and are a significant structural improvement to the tax code.

Conclusion

While the new tax law made changes to the primary family provisions, complex qualification requirements and interactions remain across the individual income tax code. These complexities make it difficult for taxpayers to understand and comply with the tax code, and lead to problems with administrability, such as improper payments of credits. Addressing the different requirements and definitions across the family provisions and consolidating these provisions would further improve the individual income tax code. Likewise, deciding which individual reforms to make permanent, well before the reforms are set to expire after 2025, would be beneficial for taxpayers.

|

Source: Internal Revenue Service, “Table 3.3 All Returns: Tax Liability, Tax Credits, and Tax Payments, by Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Tax Year 2016 (Filing Year 2017)” and author’s calculations |

||||||

| Number of CTC Claims | Amount of CTC Benefits ($millions) | Average CTC | Number of ACTC Claims | Amount of ACTC Benefits ($millions) | Average ACTC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 under $15,000 | 67,986 | $17 | $254.58 | 5,445,901 | $5,507 | $1,011.15 |

| $15,000 under $30,000 | 3,234,995 | $1,469 | $454.18 | 8,180,783 | $11,998 | $1,466.64 |

| $30,000 under $50,000 | 6,269,420 | $6,184 | $986.34 | 4,188,216 | $6,279 | $1,499.29 |

| $50,000 under $100,000 | 8,806,414 | $14,065 | $1,597.11 | 1,073,217 | $1,529 | $1,424.95 |

| $100,000 under $200,000 | 3,715,251 | $5,063 | $1,362.86 | 33,280 | $60 | $1,793.93 |

| $200,000 under $500,000 | 2,835 | $2 | $611.29 | 37 | $0.04 | $1,054.05 |

|

Source: Internal Revenue Service, “Table 3.3 All Returns: Tax Liability, Tax Credits, and Tax Payments, by Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Tax Year 2016 (Filing Year 2017)” and author’s calculations |

|||

| Child Care Credit (number of returns) | Child Care Credit (amount in millions) | Average Amount per Return | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 under $15,000 | 6,170 | $1 | $180.39 |

| $15,000 under $30,000 | 685,423 | $292 | $425.80 |

| $30,000 under $50,000 | 1,239,090 | $737 | $595.06 |

| $50,000 under $100,000 | 1,938,420 | $1,115 | $575.29 |

| $100,000 under $200,000 | 1,902,506 | $1,092 | $573.88 |

| $200,000 under $1,000,000 | 697,467 | $398 | $570.53 |

|

Source: Internal Revenue Service, “Table 3.3 All Returns: Tax Liability, Tax Credits, and Tax Payments, by Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Tax Year 2016 (Filing Year 2017)” and author’s calculations |

|||

| Earned Income Tax Credit (number of returns) | Earned Income Tax Credit (amount in millions) | Average Amount per Return | |

|---|---|---|---|

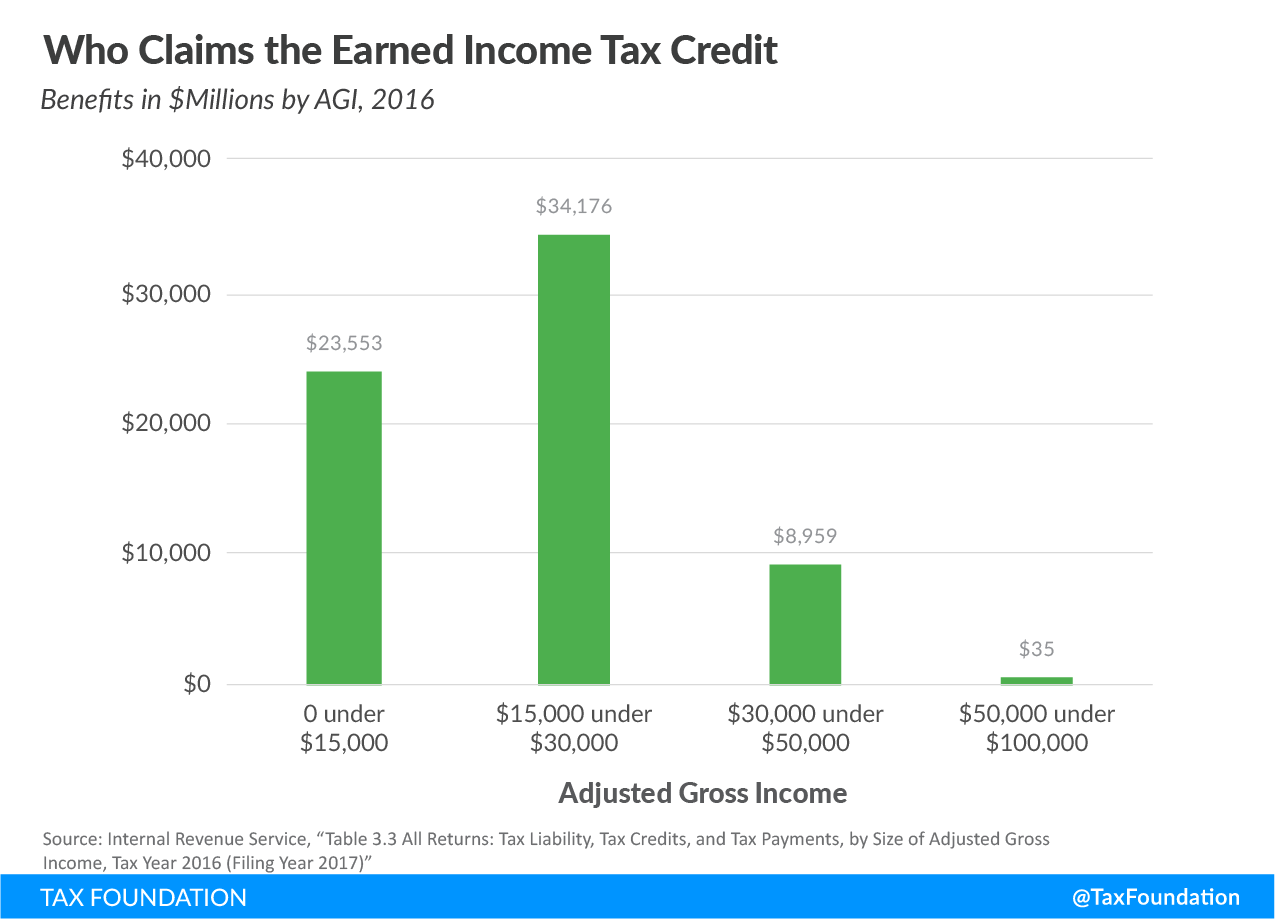

| 0 under $15,000 | 12,915,083 | $23,553 | $1,823.69 |

| $15,000 under $30,000 | 8,993,198 | $34,176 | $3,800.19 |

| $30,000 under $50,000 | 5,365,467 | $8,959 | $1,669.84 |

| $50,000 under $100,000 | 109,155 | $35 | $320.13 |

Notes

[1] Scott Greenberg, “Tax Reform Isn’t Done,” Tax Foundation, March 8, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-reform-isnt-done/.

[2] Ibid., and “Preliminary Details and Analysis of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 18, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/final-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-details-analysis/.

[3] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the Conference Agreement for H.R. 1.”

[4] See Erica York and Alex Muresianu, “The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Simplified the Tax Filing Process for Millions of Households,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 7, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/the-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-simplified-the-tax-filing-process-for-millions-of-households/.

[5] The Joint Committee on Taxation Staff, “Tables Related to the Federal Tax System as in Effect 2017 Through 2026,” April 24, 2018, 6, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5093.

[6]Intuit TurboTax, “7 Requirements for the Child Tax Credit,” Updated for Tax Year 2018, https://turbotax.intuit.com/tax-tips/family/7-requirements-for-the-child-tax-credit/L3wpfbpwQ.

[7] Intuit TurboTax, “What is the Additional Child Tax Credit,” Updated for Tax Year 2018, https://turbotax.intuit.com/tax-tips/family/what-is-the-additional-child-tax-credit/L4IBvQted.

[8] P.L. 115-97, Section 11022.

[9] Prior to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, taxpayers had to earn $3,000 to be eligible for the credit. Refundability calculated as 15 percent of income above $2,500. ($5,000 – $2,500) * 15% = $375.

[10] The credit is reduced by 5 percent for income above $200,000. ($220,000 – $200,000) * 5% = $1,000.

[11] Prior to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, phaseout of the child tax credit began at $75,000 for single taxpayers and $110,000 for married taxpayers.

[12] P.L. 115-97, Section 11022.

[13] Kelly Phillips Erb, “What The Expanded Child Tax Credit Looks Like After Tax Reform,” Forbes, Dec. 21, 2017, https://www.forbes.com/sites/kellyphillipserb/2017/12/21/how-will-the-expanded-child-tax-credit-look-after-tax-reform/#12153e314205.

[14] Internal Revenue Service, “Table 3.3 All Returns: Tax Liability, Tax Credits, and Tax Payments,

by Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Tax Year 2016 (Filing Year 2017).”

[15] The Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates Of Federal Tax Expenditures For Fiscal Years 2018-2022,” Oct. 4, 2018, 29, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5148.

[16] The Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates Of Federal Tax Expenditures For Fiscal Years 2016-2020,” Jan. 30, 2017, 37, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4971.

[17] Internal Revenue Service, “”Publication 503 (2017), Child and Dependent Care Expenses,” https://www.irs.gov/publications/p503.

[18] Ibid.

[19] See Appendix Table 2.

[20] Kimberly Lankford, “Flexible Spending Account vs. Dependent-Care Credit,” Kiplinger, Sept. 24, 2009, https://www.kiplinger.com/article/business/T020-C001-S001-flexible-spending-account-vs-dependent-care-credit.html.

[21] Internal Revenue Service, “Individual Income Tax Returns Line Item Estimates 2016,” 84-85, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/16inlinecount.pdf.

[22] The Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates Of Federal Tax Expenditures For Fiscal Years 2018-2022,” 29.

[23] Amir El-Sibaie, “Illustrating the Earned Income Tax Credit’s Complexity,” Tax Foundation, July 14, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/illustrating-earned-income-tax-credit-s-complexity/.

[24] The phaseout in this example is calculated as 7.65 percent of income above the $8,490 threshold. ($8,490 – $9,000) * 0.0765 = -$39. The maximum credit amount is reduced by $39.

[25] Internal Revenue Service, “Table 3.3 All Returns: Tax Liability, Tax Credits, and Tax Payments,

by Size of Adjusted Gross Income, Tax Year 2016 (Filing Year 2017).”

[26] Amir El-Sibaie, “Illustrating the Earned Income Tax Credit’s Complexity.”

[27] Gene Falk and Margot L. Crandall-Hollick, The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC): An Overview, Congressional Research Service, April 18, 2018.

[28] Government Accountability Office, “IMPROPER PAYMENTS Actions and Guidance Could Help Address Issues and Inconsistencies in Estimation Processes,” May 31, 2018, 30, https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/692207.pdf.

[29] Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, “The Internal Revenue Service Is Not in Compliance With Executive Order 13520 to Reduce Improper Payments,” Aug. 28, 2013, 2, https://www.treasury.gov/tigta/auditreports/2013reports/201340084fr.pdf.

[30] Gene Falk and Margot L. Crandall-Hollick, The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC): An Overview, 1.

[31] Internal Revenue Service, “2018 EITC Income Limits, Maximum Credit Amounts and Tax Law Updates,” https://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/individuals/earned-income-tax-credit/eitc-income-limits-maximum-credit-amounts-next-year.

[32] Another status, Qualifying Widow(er) with Dependent Child, may apply to some taxpayers meeting certain conditions. See Internal Revenue Service, “Determining Your Correct Filing Status,” https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/determining-your-correct-filing-status.

[33] Amir El-Sibaie, “Marriage Penalties and Bonuses under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 14, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-marriage-penalty-marriage-bonus/.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] See discussion in Amir El-Sibaie, “Marriage Penalties and Bonuses under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.”

[37] Margot L. Crandall-Hollick, “The Child Tax Credit: Current Law,” Congressional Research Service, May 15, 2018, 5.

[38] Taxpayer Advocate Service, “2008 Annual Report to Congress, Volume One,” Dec. 31, 2008, 367, https://www.irs.gov/pub/tas/08_tas_arc_legrec.pdf.

Share this article