Key Findings

- A tax expenditureTax expenditures are departures from a “normal” tax code that lower the tax burden of individuals or businesses through an exemption, deduction, credit, or preferential rate. However, defining which tax expenditures grant special benefits to certain groups of people or types of economic activity is not always straightforward. is a departure from the normal taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. code that lowers a taxpayer’s burden, such as an exemption, a deduction, or a credit.

- The list of tax expenditures in a tax system depends heavily on what one considers the normal tax code to be.

- Some tax expenditures are special preferences for particular kinds of economic activity. These may deserve elimination in order to fund broader tax relief, or they may be better off as spending programs for the purpose of more transparent government accounting.

- Some tax expenditures are attempts to change the U.S. tax system more broadly, often moving the tax code closer to systems employed by other OECD countries. These piecemeal efforts to change the U.S. tax code suggest that a broad reform to redefine the tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. would be welcome.

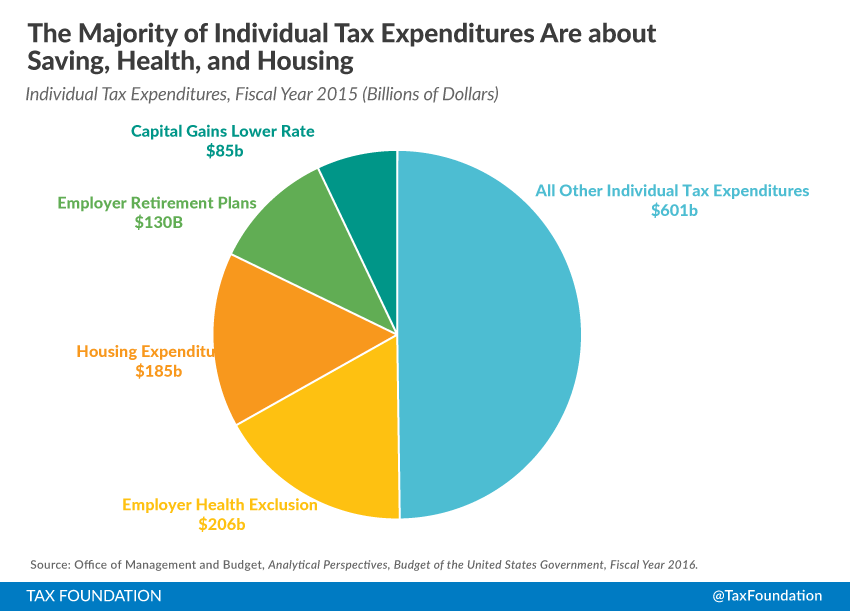

- The largest individual tax expenditures tend to prioritize health, housing, and individual saving.

- The largest corporate tax expenditure is deferral, which moves the worldwide system of corporate taxation closer to the territorial system used by most other OECD nations.

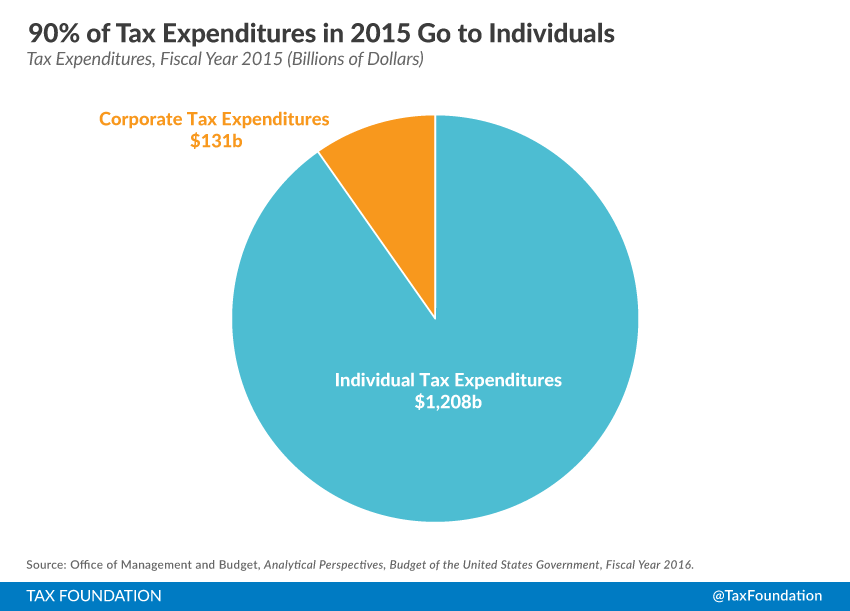

- The total cost of tax expenditures in 2015 is $1.339 trillion, with $131 billion in corporate expenditures and $1.208 trillion in individual expenditures.

Introduction

A tax expenditure is a departure from the “normal” tax code that lowers a taxpayer’s burden – for example, an exemption, a deduction, or a credit. They are called tax “expenditures” because, in practice, they resemble government spending.[1]

The most obvious kind of tax expenditure is a provision that directly lowers the tax burden for a subset of taxpayers engaged in a specific activity. For example, consider a taxpayer claiming the American Opportunity Tax Credit, who gets a lower tax bill because he has qualifying college expenses. One could achieve a functionally identical result by administering the credit through a spending program instead of the IRS. The tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. “spends” by forgoing the revenue collection in the first place.

However, measurement of tax expenditures can often be more complicated than the clear-cut example above. What one considers to be a tax expenditure tends to depend heavily on what one considers the “normal” tax code to be. As a result, both deliberate broad-based changes to the tax code and narrow tax preferences can be labeled as tax expenditures.

The U.S. has both an individual income tax and a corporate income tax: therefore, there are both individual and corporate tax expenditures. The individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. is the larger tax, and consequently it has the larger tax expenditures. This report will review some of the most significant expenditures in the individual and corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. codes.

Lawmakers interested in reforming this area of the tax code should examine each expenditure individually and first consider what kind of expenditure it is: does it move us toward a different tax system? Is it spending on an important priority of society at large? Or does it narrowly provide a preference to a specific industry or activity? Answering these questions and classifying the expenditures is critical in determining which of them are worth keeping.

A Brief History of Tax Expenditures

The idea of the tax expenditure was developed in the 1960s by Assistant Secretary of the Treasury Stanley Surrey. It officially became part of the tax policy lexicon in 1974, when Congress mandated that tax expenditures be recorded as part of the annual budget. Under that act, tax expenditures were officially defined as “revenue losses attributable to provisions of the Federal tax laws which allow a special exclusion, exemption, or deduction from gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total of all income received from any source before taxes or deductions. It includes wages, salaries, tips, interest, dividends, capital gains, rental income, alimony, pensions, and other forms of income. For businesses, gross income (or gross profit) is the sum of total receipts or sales minus the cost of goods sold (COGS)—the direct costs of producing goods, including inventory and certain labor costs. or which provide a special credit, a preferential rate of tax, or a deferral of tax liability.”[2]

This is a useful definition for highlighting spending on specific industries or social priorities, and estimating the cost of including those provisions in the tax code. However, any measure of tax expenditures that begins from a particular tax system will always treat any change to it – no matter how broad – as a tax expenditure. It is therefore important to separate broad-based changes to the tax code from narrow preferences.

What is the Normal Tax Code?

Given that a tax expenditure is defined as a departure from the “normal” tax code, the nature of tax expenditures depends crucially on what the “normal” tax code is. The Treasury Department and Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) have adopted similar definitions, but while these definitions have been consistent, they are not economically coherent.

The federal tax system is built on a poor intellectual foundation; it relies heavily on a definition of income developed by economists Robert Haig and Henry Simons almost a century ago.[3] The Haig-Simons definition of income is that income equals the sum of your consumption and your change in net worth; I = C + ΔNW. This is a useful accounting identity. It tells us that what we don’t spend on consumption becomes accumulated saving. However, it is not necessarily a good tax base.

There is an issue with including both a person’s consumption (C) and his or her change in net worth (ΔNW) in the tax base. The issue is that a change in one’s net worth usually becomes consumption at a later date.[4] (For example, an average individual accumulates net worth throughout her working life and spends it down in retirement.) As a result, the Haig-Simons definition single-counts some kinds of consumption, but double-counts other kinds for the purposes of taxation.

A distortion like this one – where some kinds of economic production get taxed more than other kinds – is generally a drawback. But this particular distortion is unusually powerful because it artificially reduces the after-tax return to saving and investment. Since people’s saving and investment decisions are sensitive to expected after-tax returns, the result is substantially less capital formation, which means smaller increases over time in productivity, incomes, and employment.

There are, of course, alternative tax bases. Among these are sales taxes, value-added taxes, excise taxes, corporate income taxes, payroll taxes, and property taxes. All of these tax bases are used in various places around the world, and all have benefits and drawbacks. There is no objective reason to define any particular tax base as “normal” for the purposes of counting tax expenditures.

The chosen “normal” tax code in Washington includes an individual income tax based on the Haig-Simons definition paired with a corporate income tax – although Simons regarded the corporate income tax as a double tax that he did not include in his definition of income. At times, government bureaus also measure tax expenditures from the payroll taxes that fund social insurance programs like Social Security.

Even after defining the “normal” tax base, there are still many issues in methodology. For example, measuring some changes in net worth (like capital gains) is a difficult problem. A taxpayer’s net worth may include assets with ever-changing values. For this reason, changes in asset value are usually only recorded as capital gains (or losses) upon the sale of the asset.

This is certainly a departure from a pure Haig-Simons income tax – and as a “deferral of tax liability,” it would be considered a tax expenditure under the Haig-Simons definition – but it is too difficult to calculate. As a result, it is usually not considered a tax expenditure, and the “normal” tax code measures changes in net worth only when they are realized.

This is one of the many compromises that the Treasury and JCT have to make in order to nail down a definition of tax expenditures. Some of these choices are extremely significant. For example, progressive income tax bracketsA tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. are not counted as a “preferential rate of tax.” As a result, the official list of tax expenditures appears to favor wealthier taxpayers, because the progressivity of the tax system is already assumed in defining the base.[5]

Additionally, personal exemptions and the standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. Taxpayers who take the standard deduction cannot also itemize their deductions; it serves as an alternative. are generally considered not to be tax expenditures, but rather part of a structure that defines a zero-rate bracket.[6] Personal exemptions are a particularly curious example, because they effectively lower the tax bill for adults with more dependents. Child tax credits, which serve the exact same purpose, are considered to be tax expenditures.

Additionally, the corporate income tax (at any rate Congress chooses) is considered “normal,” even though it is duplicative with income taxes on shareholders.[7] This corporate tax code gets deductions for employee compensation and a particular kind of deduction for capital costs, known as the alternative depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. system (ADS).[8] There is no particular reason to believe that this deduction for capital costs is the only “normal” one, and the U.S. has in fact experimented with many different systems over the last century. ADS, however, was the method in use at the time that tax expenditures were invented as a concept.

Given all of these metaphysical questions about what constitutes a normal tax structure, the true nature of tax expenditures will always be somewhat subjective. The particular nature of what constitutes a tax expenditure in Washington is partially economics, partially one’s value judgments, and partially historical accident. However, rather than devising an alternative measure of tax expenditures, this report will concern itself with tax expenditures as measured in practice.

Relative Size of Corporate versus Individual Tax Expenditures

The majority of the expenses incurred by tax expenditures comes from the individual side. For Fiscal Year 2015, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) projects $131 billion in corporate tax expenditures and $1.208 trillion in individual tax expenditures for over $1.339 trillion in total.[9]

Chart 1.

Largest Individual Tax Expenditures

The largest individual tax expenditures usually have one of two different roles. The first role is to prioritize certain kinds of consumer spending (especially housing and healthcare) over others. This is a practice that should be reviewed with skepticism; the IRS’s primary purpose should be to raise revenue, not to encourage particular types of economic activity.

However, a second purpose for individual tax expenditures is to move the tax code away from a normal Haig-Simons income tax and toward other kinds of equally normal tax systems. Rather than view these as some kind of special tax break, or a departure from the normal tax system, we should see these as an attempt to move toward a different tax system entirely.

Here is a summary of the five largest individual tax preferences with their annual costs, as defined and estimated by OMB.[10] It includes both tax expenditures that prioritize certain specific kinds of economic activity and those that redefine the tax system more broadly.

1. The Exclusion of Employer Contributions for Medical Insurance Premiums ($206 billion). Employer contributions to insurance premiums reflect a tax preference for those taxpayers with employer-provided health insurance, because they receive a form of labor compensation that goes untaxed. This is easily the largest tax preference – for example, larger than all corporate tax expenditures combined.[11]

It is also the clearest example of Congress prioritizing some economic activities over others. Health is no doubt important, but the use of the tax code to bundle employment together with health insurance is worthy of skepticism.

Recent Congresses have shown some willingness to chip away at this preference; for example, the “Cadillac TaxThe Cadillac Tax is a 40 percent tax on employer-sponsored health care coverage that exceeds a certain value. The aim: to curb health-care cost growth, reduce favorable tax treatment of employer-provided insurance, and help fund the Affordable Care Act (ACA). It was repealed in late 2019 before taking effect. ” in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act levies a tax on employer contributions above a certain threshold, which partly rolls back the exclusion.[12] Additionally, the recent tax reform proposal by Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp included employer-provided health contributions in its definition of modified adjusted gross income.[13]

2. Lower Rate for Capital Gains ($85 billion). This is listed as a tax expenditure because the normal tax code defined by JCT includes a full Haig-Simons individual income tax in addition to a corporate income tax. This tax expenditure, in some ways, returns to a pure Haig-Simons definition, because it acknowledges and compensates for the corporate income tax on the individual side. Shareholders can pay taxes either individually or through corporations, and the U.S. income tax code – in practice – splits the burden between the two. Other countries, like Australia, also split this burden, but they do it in a more explicit and intentional way through corporate integration.[14]

This is an example of a reform that is clearly designed as a move toward a different kind of tax system (perhaps, an equal tax on all income with corporate integration) but it does not represent special tax treatment for a specific sector of the economy. Rather, it is a deliberate attempt to move the tax code past the definition of normalcy that was chosen in the 1970s.

3. Exclusion of Net Imputed Rental Income ($79 billion). This line item comes from owner-occupied housing. In our tax code, if you rent real estate to someone else, you pay taxes on that rental income. However, if you “rent” the real estate to yourself by living in your own home, there is no market income to tax. Your “income” comes from the personal benefit you get from your home. This benefit is called imputed rent. This exclusion is considered a tax expenditure due to the definition of income used in the tax code.

In practice, this tax expenditure exists mostly because imputed rent is not an easy tax base to understand or assess.

4. Deductibility of Mortgage Interest on Owner-Occupied Housing ($69 billion). This is the largest individual tax deductionA tax deduction allows taxpayers to subtract certain deductible expenses and other items to reduce how much of their income is taxed, which reduces how much tax they owe. For individuals, some deductions are available to all taxpayers, while others are reserved only for taxpayers who itemize. For businesses, most business expenses are fully and immediately deductible in the year they occur, but others, particularly for capital investment and research and development (R&D), must be deducted over time. and the third-largest individual tax expenditure. There is some logic with this expenditure: if interest income on mortgages is taxable, then the lost income from paying that interest should be deductible – otherwise the borrower and the lender are taxed on the same income, creating a double tax. However, this would be better addressed with some type of comprehensive treatment of interest rather than a specific one for owner-occupied housing alone.[15]

5. Defined Contribution Employer Plans ($68 billion). 401(k) plans and similar retirement vehicles allow taxpayers to deduct retirement savings and pay income taxes only when those savings are withdrawn. Defined benefit employer plans ($45 billion) and individual retirement accounts ($17 billion) are treated similarly, but counted as separate tax expenditures. These are lowered tax burdens only in the sense that they are considered a “deferral” of tax liability from what is seen as the normal tax code. Many tax systems – like those for pensions in most countries, not just ours – defer tax liability on pension contributions until the money is paid.

More broadly, this represents a move toward a style of tax known as the consumed income tax or inflow-outflow tax.[16]

Combining some of the large individual tax expenditures with similar purposes reveals that only a few big priorities motivate most tax expenditure spending. The three largest housing expenditures, for example – including the imputed rent exclusion, the mortgage interest deduction, and the capital gains exclusion on housing sales – combine for $185 billion. The employer-provided health insurance exclusion accounts for $206 billion. Defined benefit and defined contribution plans together with individual retirement accounts add another $130 billion.

Many of these large tax expenditures are a deliberate effort to mitigate the issues with the normal tax code defined in 1974. However, these efforts are stronger for owner-occupied housing than most other kinds of investment, which shows that preferential treatment of particular sectors of the economy is also a priority in the tax expenditure budget.

The employer health exclusion is the biggest example of a tax expenditure used to prefer a particular sector of the economy, but there are smaller ones as well. These include the credits for Empowerment Zones, the DC Enterprise Zone, and Renewal Communities. These, for example, are designed to favor certain areas of the country with lower taxes. This is spending through the tax code – the original intended definition of a tax expenditure.

Chart 2.

Largest Corporate Tax Expenditures

Corporate tax expenditures, collectively, are far smaller than the individual tax expenditures. Nonetheless, some of them are quite substantial. The corporate tax code follows a similar story to the individual tax code. Some tax expenditures are legitimate attempts to make broad-based modifications to the tax code. Others, though, are attempts to favor certain sorts of economic activity over others. Here are the four most significant corporate tax preferences:

1. Deferral of Income from Controlled Foreign Corporations ($65 billion). Deferral is the largest corporate tax expenditure, though still smaller than any of the big individual tax expenditures. This tax expenditure represents the fact that the additional domestic tax on foreign earnings (i.e., the repatriationRepatriation is the process by which multinational companies bring overseas earnings back to the home country. Prior to the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the US tax code created major disincentives for US companies to repatriate their earnings. Changes from the TCJA eliminate these disincentives. tax), which is over and above what is paid abroad, can be deferred as long as the earnings remain invested abroad.[17]

This expenditure, like many others, is entirely an artifact of what is assumed to be normal. The corporate tax considered to be normal by JCT is a “worldwide” system of corporate taxation. However, most countries in the OECD have now moved to territorial systems of corporate taxation, where countries tax only the business activity located within their jurisdictions.[18]

Furthermore, JCT considers it normal for the businesses to owe their taxes immediately when the income is earned, rather than when it is repatriated. This is far from a normal tax system; if anything, it is the opposite. In the few remaining countries with a worldwide tax systemA worldwide tax system for corporations, as opposed to a territorial tax system, includes foreign-earned income in the domestic tax base. As part of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the United States shifted from worldwide taxation towards territorial taxation. , all have deferral as a way to keep their multinational companies somewhat competitive with those based in territorial countries.[19]

Indefinite deferral approaches a territorial tax system of full exemption of foreign earnings, although it involves excessive tax planning and administrative costs and also results in the problem of locked out profits.

2. Deduction for U.S. Production Activities ($11 billion). Also known as Section 199, this is a 9 percent deduction for businesses with qualified production activities in the United States. Mathematically, it is equivalent to reducing the corporate income tax rate from 35 percent to 31.85 percent on income from qualified domestic production activities. Although this is certainly an incentive for businesses to invest in the United States, and it is taken by most industries, it is not applied to every industry. If this deduction were simply turned into a neutral rate reduction for all business, it would be better policy, and it would no longer be considered a tax expenditure.

3. Exclusion of Interest on State and Local Bonds for Public Purposes ($9 billion). Interest on certain municipal bonds is excluded from federal taxation. The loss of tax revenue from corporations that hold these bonds is expected to be $9 billion in 2015. However, this measure is typically defined as a measure of aid to state and local governments, not as aid to the lenders.[20] In practice, bondholders have to pay a premium for these tax-exempt bonds – that is, they are willing to accept lower interest rates. The money lost by the federal government, then, is given to states in the form of lower borrowing costs.

While many states and municipalities rely on federal aid, it may be better to fold this kind of aid into an existing spending program for all states, rather than subsidizing states explicitly for using debt financing.

4. Accelerated Depreciation of Machinery and Equipment (-$10 billion). This expenditure is negative for fiscal year 2015, but it is worth mentioning because its value varies from year to year, and it could by other measures be considered a large tax expenditure.[21] It comes from the corporate tax code’s treatment of investment. When a physical asset – like a factory – is purchased, the corporate income tax code recognizes it as a legitimate business expense. However, its purchase price is written off over a depreciation schedule of years or decades and not all counted immediately. There are infinitely many schedules possible, specific to each individual kind of asset a business could possibly buy.

The Joint Committee defines the alternative depreciation system (ADS) as the normal way to account for business deductions, but there is nothing particularly special about it; as its name implies, it was an alternative to previous depreciation schedules. Since then, newer depreciation schedules have succeeded ADS, and they are no less legitimate. [22] ADS has not been used for many years; the current system is called the Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS).

Lately, some tax laws on depreciation have fallen in with the extenders – a grab bag of tax provisions that are handled on an ad-hoc basis from year to year.[23] In the end, measurements of this tax expenditure are volatile, due to the unpredictability of depreciation policy, the complexity of the calculations, and the outdated nature of the baseline to which current policy is compared.

However, there is a better way to go forward. While depreciation is a useful accounting concept to calculate book values of corporations, the economic costs of an asset should be reflected by expensing; that is, the cost of the asset should be deductible in the year that the money is actually spent, properly reflecting the time value of money.[24] This is the sort of deduction that business transfer taxes or VATs use, and it is in many respects much more normal than anything that the U.S. has used in the past few decades.[25]

These expenditures make up a large portion of corporate tax expenditures; in fact, half of the corporate tax expenditure budget for fiscal year 2015 comes from deferral alone, with the other tax expenditures discussed above taking up much of the remainder.

Chart 3.

Some Tax Expenditures Change the Tax Base, Others Are Special Preferences

In truth, America’s corporate and individual income taxes are not quite income taxes; they are hybrids that include many elements of other tax systems.

For example, within the individual income tax code, the IRA, the 401(k), and the defined-benefit pension are all nods toward a consumed income tax. Within the corporate code, deferral is a nod toward the territorial system employed by most of the OECD.

It is often said that the U.S. is also the only country in the OECD without a value-added tax (VAT).[26] But taken as a whole, businesses in the U.S. do pay tax on something approximating the VAT base; business inputs are exempted, earnings to capital are taxed through the corporate income tax, and earnings to labor are taxed through the employer-side payroll taxA payroll tax is a tax paid on the wages and salaries of employees to finance social insurance programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance. Payroll taxes are social insurance taxes that comprise 24.8 percent of combined federal, state, and local government revenue, the second largest source of that combined tax revenue. .

Tax expenditures can be divided into roughly three categories. The first, and generally the largest in value, is the kind described above, which modernize our tax code and move it toward some of the tax systems used by our trading partners. The second kind are expenditures like the child tax credit or the health exclusion: ones designed with broader social policy priorities in mind. And the final kind are subsidies to specific industries.[27]

Tax expenditures in the first category should be taken seriously, and most of them were made with legitimate policy ideas in mind. They should be understood not as special preferences that move us away from a normal tax code, but rather, as deliberate and broad provisions to challenge the idea of what a normal tax code should be. Under other, equally valid tax systems used by our trading partners, they would not be considered tax expenditures at all.

Tax expenditures in the second category – expenditures like the child tax credit or the employer health exclusion – are quite obviously spending provisions reflecting a legitimate governing priority. A society should, of course, care deeply about its children and its health. However, the way in which it provides for these priorities should be up for debate.

Only the tax expenditures in the third category – ones designed entirely to subsidize specific industries – deserve outright elimination. This kind of expenditure is usually the kind that people are most eager to eliminate. However, precisely because people are so eager to eliminate them, there are fewer of these than one might imagine.

Conclusion

Determining what constitutes a tax expenditure is a subjective and difficult exercise. However, it has important implications for tax policy, because the elimination of tax expenditures is a popular way to pay for tax reform. It is therefore important to remember that a haphazard elimination of every tax expenditure, regardless of kind, would be misguided.[28]

Not all tax expenditures are equally worthy of elimination. It is important to ask, for each expenditure, whether it serves a reasonable purpose and whether it accomplishes that purpose in a reasonable way. This trillion-dollar area of the tax code deserves examination and a degree of healthy skepticism, but it doesn’t deserve across-the-board elimination.

[1] Stanley Surrey, Federal Income Tax Reform, Harvard Law Review, Vol. 84, No. 2, pg. 352, Dec.1970, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1339715?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

[2] Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974, 2 U.S.C. § 622(3), http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCODE-2010-title2/pdf/USCODE-2010-title2-chap17A-sec622.pdf.

[3] Henry C. Simons, Personal Income Taxation: The Definition of Income as a Problem of Fiscal Policy, University of Chicago Press, 1938. See also Robert M. Haig, The Concept of Income—Economic and Legal Aspects, in The Federal Income Tax, Robert M. Haig ed., Columbia University Press, 1921.

[4] Milton Friedman, A Theory of the Consumption Function, Princeton University Press, 1957, http://papers.nber.org/books/frie57-1.

[5] Michael Schuyler, Baked In the Cake: Why the Progressivity of the Income Tax Isn’t Visible in the Distribution of Tax Expenditures, Tax Foundation Special Report No. 212, Jan. 13, 2014, https://taxfoundation.org/article/baked-cake-why-progressivity-income-tax-isn-t-visible-distribution-tax-expenditures.

[6] Joint Committee on Taxation, Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2014-2018, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4663.

[7] For an example of the limitations of this definition, consider a tax plan that increases individual income taxes on corporate income by a percentage point, but reduces corporate income taxes by a percentage point. Most observers would say this is an inconsequential plan that mostly cancels itself out, but it would be a reduction in tax expenditures under JCT’s definition.

[8] Joint Committee on Taxation, Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2014-2018, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4663.

[9] Office of Management and Budget, Analytical Perspectives: Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2015, at Tables 14-1 to 14-4, Feb. 2015, http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Analytical_Perspectives.

[10] Id.

[11] In addition to this lost income tax revenue, OMB estimates that in 2015 it will reduce payroll tax revenue by $128 billion for a combined total revenue loss of $319 billion. This is larger than corporate tax revenue collections in a typical year.

[12] Kyle Pomerleau, Obamacare’s “Cadillac Tax” Working as Planned, Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog, May 29 2013, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/obamacares-cadillac-tax-working-planned.

[13] Though eliminating the tax exclusions for employer provided health insurance would move toward a neutral base, a system including a measure of modified adjusted gross income would not.

[14] Kyle Pomerleau, Eliminating Double TaxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. through Corporate Integration, Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 453, Feb. 23, 2015, https://taxfoundation.org/article/eliminating-double-taxation-through-corporate-integration.

[15] Alan Cole, A Partial Defense of the Mortgage Interest DeductionThe mortgage interest deduction is an itemized deduction for interest paid on home mortgages. It reduces households’ taxable incomes and, consequently, their total taxes paid. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) reduced the amount of principal and limited the types of loans that qualify for the deduction. , Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog, Aug. 20, 2013, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/partial-defense-mortgage-interest-deduction.

[16] Norman Ture and Stephen Entin, The Inflow Outflow Tax – A Saving-Deferred Neutral Tax System, Institute for Research on the Economics of Taxation, 1997, http://iret.org/pub/inflow_outflow.pdf.

[17] See Robert Carroll, The Importance of Tax Deferral and A Lower Corporate Tax Rate, Tax Foundation Special Report No. 174, Feb. 2010, https://files.taxfoundation.org/docs/sr174.pdf.

[18] Philip Dittmer, A Global Perspective on Territorial Taxation, Tax Foundation Special Report No. 202, Aug. 10, 2012, https://taxfoundation.org/article/global-perspective-territorial-taxation.

[19] New Zealand is one country that tried the system of worldwide taxation without deferral. This was so harmful to economic growth that the country abandoned the effort and switched to a territorial tax systemTerritorial taxation is a system that excludes foreign earnings from a country’s domestic tax base. This is common throughout the world and is the opposite of worldwide taxation, where foreign earnings are included in the domestic tax base. in 2009. See William McBride, New Zealand’s Experience with Territorial Taxation, Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 375, June 19, 2013, https://taxfoundation.org/article/new-zealands-experience-territorial-taxation.

[20] This is explicitly noted in the OMB’s Analytical Perspectives.

[21] Over the full budget window, for example, the OMB budget projects the expenditure to cost $307 billion.

[22] ADS is often considered to be the closest depreciation schedule to real-life economic depreciation, but it is effectively impossible for the IRS or any other organization to measure the lives of assets in real time. Any depreciation schedule is an approximation.

[23] Andrew Lundeen & Kyle Pomerleau, Not All Tax Extenders Are Worth Extending, Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog, Jan. 22, 2014, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/not-all-tax-extenders-are-worth-extending.

[24] Stephen Entin, The Tax Treatment of Capital Assets and Its Effects on Growth: Expensing, Depreciation, and the Concept of Cost RecoveryCost recovery refers to how the tax system permits businesses to recover the cost of investments through depreciation or amortization. Depreciation and amortization deductions affect taxable income, effective tax rates, and investment decisions. in the Tax System, Tax Foundation Background Paper No. 67, Apr. 24, 2013, https://files.taxfoundation.org/docs/bp67.pdf.

[25] Unlike a business tax code with depreciation schedules, a business tax code with expensing can easily determine the appropriate size of deductions. It simply bases them on actual cash flow, a method that is neutral across all business.

[26] For more on international tax systems, see Kyle Pomerleau and Andrew Lundeen, 2014 International Tax Competitiveness Index, Tax Foundation, Sep. 15, 2014, https://taxfoundation.org/article/2014-international-tax-competitiveness-index.

[27] William McBride, A Brief History of Tax Expenditures, Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 391, Aug. 22, 2013, https://taxfoundation.org/article/brief-history-tax-expenditures.

[28] Michael Schuyler & Stephen J. Entin, The Economics of the Blank Slate: Estimating the Effects of Eliminating Major Tax Expenditures and Cutting Tax Rates, Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 378, July 26, 2013, https://files.taxfoundation.org/docs/ff378.pdf.