Key Findings

- On April 17, 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear arguments in South Dakota v. WayfairSouth Dakota v. Wayfair was a 2018 U.S. Supreme Court decision eliminating the requirement that a seller have physical presence in the taxing state to be able to collect and remit sales taxes to that state. It expanded states’ abilities to collect sales taxes from e-commerce and other remote transactions. , Inc., on the constitutionality of a South Dakota law requiring collection of the state’s sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. by internet vendors with at least 200 transactions or $100,000 in sales to South Dakota residents.

- The appellants in the case seek to overturn the Quill decision of 1992, which holds that states cannot force sales taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. collection by vendors who do not have personnel or property in the state (the “physical presence” standard).

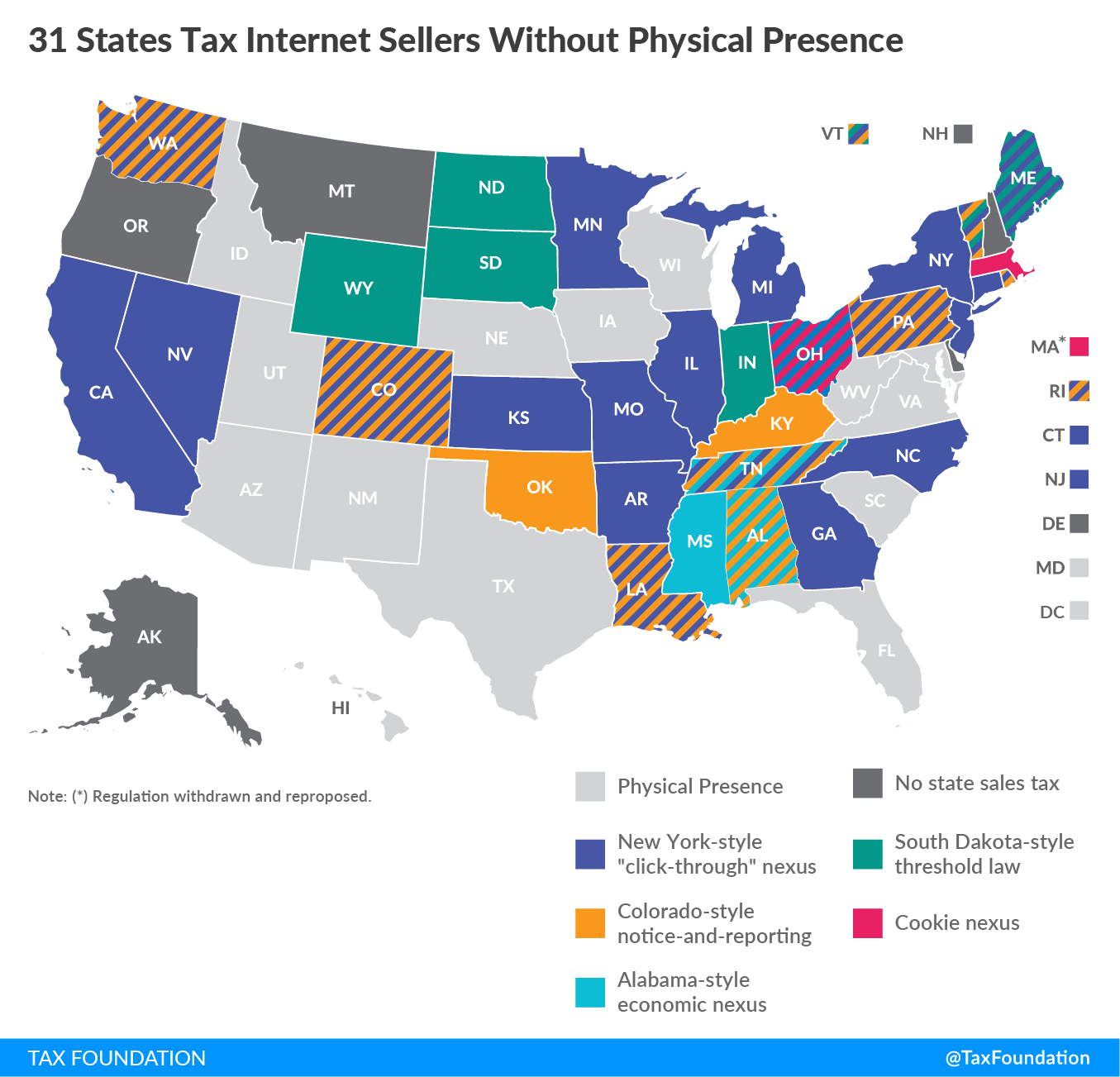

- Contrary to claims that physical presence is the status quo standard, 31 of the 45 states with a sales tax have already expanded their state tax collection authority to sellers with no physical presence in the state.

- Some of these laws are well-crafted, but many are not and are imposing significant and disparate compliance burdens on out-of-state sellers. To date, federal and state courts have upheld these laws, and there is strong likelihood that the U.S. Supreme Court will do so as well.

- Congress may act before the Court does. The proposed Remote Transactions Parity Act (RTPA), sponsored by Rep. Kristi Noem (R-SD), would authorize states to collect sales taxes on internet purchases made by their residents, so long as the state adopts meaningful simplifications to their sales tax system. RTPA incorporates more taxpayer protections than earlier federal proposals and would ultimately make sales tax collection simpler and easier than payroll and income tax withholdingWithholding is the income an employer takes out of an employee’s paycheck and remits to the federal, state, and/or local government. It is calculated based on the amount of income earned, the taxpayer’s filing status, the number of allowances claimed, and any additional amount of the employee requests. or unemployment tax payments in states that choose to adhere to it.

- Absent Court or congressional action, states are creating the scenario that the Commerce Clause sought to avoid: unlimited tax authority that burdens interstate commerce. Congressional proposals like the RTPA, Mobile Workforce, the Business Activity Tax Simplification Act (BATSA), and the Digital Goods and Services Tax Fairness Act would replace the physical presence standard with one that prevents taxation based on nondirected and transient activity such as internet cookies, referral links, and airport stopovers.

Many states have used and abused the “physical presence rule” to greatly expand their taxing powers. These enactments include New York-style click-through nexus, Colorado-style reporting and notification, and Massachusetts-style cookie nexus. Further, several states and courts have declined to apply the physical presence standard to business and individual income taxes.

Figure 1.

22 States Have Adopted Click-Through Nexus Laws

In 2008, New York adopted a law expanding its definition of physical presence to include out-of-state sellers who (1) have compensated referral agreements with in-state websites and (2) have in-state sales of at least $10,000 per year.[1] Nexus is presumed unless rebutted. This statute was upheld in Overstock.com, Inc. v. New York State Dep’t of Taxation & Fin., finding that contracts with in-state nonemployees who refer customers for compensation constitute substantial nexus.[2] Twenty-one states have adopted identical or nearly-identical statutes, with dollar threshold amounts ranging from $2,000 to $50,000, and some with no ability to rebut the nexus presumption.[3] These statutes create physical presence when a retailer uses an independent contractor even if those contractors do not engage in maintaining an in-state market or a substantial flow of goods. While these statutes provide for an ability to rebut the presumption that solicitation occurred, rebutting such presumption would inherently be futile, as it is hard to prove what has been done by individuals on the internet. As a result, due to the global nature of the internet, these click-through laws apply more broadly and encompass not only retailers who target sales within a given state, but also retailers who may not actually produce a sale in the given state.

10 States Have Adopted Notice-and-Reporting Laws

In 2010, Colorado enacted a statute requiring noncollecting retailers to: (1) provide Colorado purchasers a “transactional notice” at the time of purchase, informing them that the purchase may be subject to Colorado’s use tax; (2) provide an “annual purchase summary” with the dates, amounts, and categories of purchases of all Colorado purchasers with purchases over $500; and (3) file with the Colorado Department of Revenue an annual report listing their customers’ names, addresses, and total purchases.[4] In Direct Mktg Ass’n v. Brohl, the Tenth Circuit upheld the Colorado statute after concluding that Quill’s holding applied to sales and use tax collection and not to the imposition of regulatory requirements.[5] Nine states have adopted similar laws.[6] Reporting requirements under these notice-and-reporting statutes are deliberately cumbersome so as to compel collection. These statutes also raise privacy concerns relating to the requirement to notify state officials about what each customer purchases online.

Three States Have Adopted Sales Tax Provisions Which Ignore Physical Presence Entirely

Three states have adopted more far-reaching abrogation on their tax powers. These regulations require sales tax collection by essentially any economic actor within the state. Alabama requires any vendor with more than $250,000 in Alabama sales and who is engaged in any of a broad list of activities to collect sales tax.[7] Mississippi adopted an identical regulation, while Tennessee has a similar one with a higher $500,000 threshold.[8]

Two States Have Adopted Cookie Nexus Provisions

On September 22, 2017, Massachusetts proposed Reg. 830, which would have required vendors with more than $500,000 in sales into Massachusetts from internet transactions and 100 or more transactional sales into the state during the previous twelve months to collect and remit sales and use tax if the vendor: (1) has established a physical presence through property interests in and/or the use of in-state software (making “apps” available to be downloaded by in-state residents) and ancillary data (placing “cookies” on in-state residents’ web browsers), (2) has contracts and/or relationships with content distribution networks, or (3) uses marketplace facilitators and/or delivery companies.[9] Massachusetts subsequently withdrew the regulation but has begun the process of reissuing it. Ohio, however, adopted the standard as law, effective January 1, 2018.[10] Discussion among state tax administrators suggests other states may consider adopting similar app and cookie nexus provisions. Under this “cookie nexus” standard, Massachusetts and Ohio have the power to tax any online store on the planet if one of their residents accesses the vendor’s website or downloads its app.

Six States Have Adopted South Dakota’s Challenged Law

South Dakota’s law minimizes the burden of sales tax collection to the extent practicable, by: (1) adhering to interstate standards of sales tax administration, (2) requiring uniformity between state and local sales tax bases, (3) minimizing number of local sales tax rates, which in South Dakota must be either 1 or 2 percent, (4) taxing virtually all final retail transactions under its sales and use tax, without arbitrary exemptions or confusing special tax rates, (5) adopting a meaningful de minimis threshold likely to exclude interstate activity where state burdens exceed state benefits, and (6) barring retroactive collection.[11] In addition, the state does not discriminate against interstate commerce, subjecting out-of-state retailers to the same taxes paid by in-state retailers, and the statute’s sales and use tax applies only to South Dakota’s fair apportioned share of interstate commerce, purchases made by South Dakota residents not taxed by any other state. South Dakota’s law has served as the template for laws in Indiana, Maine, North Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming, with similar thresholds of $100,000 in annual sales or 200 individual transactions in the state.[12] The Vermont and Wyoming laws are on hold pending this Court’s decision in this case, and the Indiana law is being challenged.[13]

Many States Ignore Physical Presence for Income and Business Taxes

Ohio, Washington, and West Virginia have enacted laws, and courts in those states have upheld them, which impose business taxes without regard to physical presence.[14] States increasingly apply business taxes to out-of-state businesses without an in-state physical presence, dragging out-of-state sellers into their taxing regime based on as little as one transaction. Bloomberg BNA’s lengthy Survey of State Tax Departments lists hundreds of scenarios in which states conclude nexus has been established by non-physically-present businesses.[15]

U.S. Supreme Court Is Likely to Uphold State Powers in Some Way

The pending South Dakota v. Wayfair case has several possible outcomes: (1) a reaffirmation of Quill, which few consider likely; (2) a “narrow” ruling upholding the South Dakota law at issue but giving no guidance for future cases, which would likely cause a free-for-all of states adopting all sorts of harmful legislation expanding their tax powers; (3) a broad ruling letting states do whatever they want; or (4) a ruling upholding the South Dakota law but clearly stating what kind of state taxation of interstate commerce is constitutional. On March 5, 2018, the Tax Foundation has submitted an amicus brief, in support of neither party, urging that last approach.[16]

Our brief argues that the South Dakota law is constitutional, but Quill need not be overturned. The physical presence standard from that case adopted a proxy for what truly matters, constitutionally: state taxes cannot burden interstate commerce, cannot discriminate against interstate commerce, and cannot tax more than their fair share of interstate commerce. Our brief cites dozens of past cases, as well as contemporaneous statements by the Founders, to support this reading of the Commerce Clause. In the areas of income and business taxes, physical presence has actually led to more extensive state taxation of interstate commerce, with taxes on businesses and business travelers with only transient or incidental personnel in the state.

RTPA and Other Proposals Would Reestablish Meaningful Limits on State Tax Powers

Various congressional proposals seek to pare back state tax authority to ensure that state taxes not burden interstate commerce, that they not discriminate against interstate commerce relative to in-state commerce, and that they not tax more than their share of interstate commerce:

- the Mobile Workforce bill, which will limit state income taxes only to those physically present in the state for at least 30 days (many now tax from day 1);

- the Business Activity Tax Simplification Act (BATSA), which will require a threshold of activity in the state before corporate or gross receipt tax is owed;

- the Digital Goods and Services Tax Fairness Act, which defines which one state (the address of the purchaser) gets to tax digital transactions that are everywhere and nowhere; and

- the Remote Transactions Parity Act (RTPA), which authorizes states to collect sales taxes on internet purchases made by their residents (and only their residents, physically present in the state), so long as the state adopts meaningful simplifications to their sales tax system.[17]

Each of these proposals go beyond the physical presence standard, as that standard has allowed states to tax based on nondirected and transient activity such as internet cookies, referral links, and airport stopovers.

Conclusion

Absent congressional or Court action, states are creating the scenario that the Commerce Clause sought to avoid: the voice for sound tax policy, for levying taxes only from those in-state businesses and residents who benefit from provided services, is overridden by those seeking to use the state tax code to benefit in-state people and businesses. Congress should act to rebuild limits on state tax power, and these limits should include a nexus standard that scales with the burden it imposes. Congressional proposals like the RTPA, Mobile Workforce, and BATSA would replace the physical presence standard with one that prevents taxation based on nondirected and transient activity such as internet cookies, referral links, and airport stopovers.

[1] See N.Y. Tax Law § 1101(b)(8)(vi).

[2] 987 N.E.2d 621 (N.Y. 2013).

[3] Ark. Code § 26-52-117(d)-(e) ($10,000 threshold, rebuttable); Cal. Rev. & Tax § 6203(b)(5) ($10,000 threshold, rebuttable, also requires at least $1 million in national sales); Colo. Rev. Stat. 39-26-102(e) ($50,000 threshold, rebuttable); Conn. Gen. Stat. § 12-407(a)(12)(L) ($2,000 threshold, non-rebuttable); Ga. Code § 48-8-2(8)(M) ($50,000 threshold, rebuttable); 35 Ill. Comp. Stat. 105/2 & 110/2 ($10,000 threshold; non-rebuttable; statute; see Performance Marketing Ass’n, Inc. v. Homan, 998 N.E. 2d. 54 (Ill. 2013) (holding the statute was preempted by federal law and violated the commerce clause of the United States Constitution); Kan. Stat. § 79-3702(h)(2)(C) ($10,000 threshold; rebuttable); 2016 La. H.B. 30, 1st Extra Sess. ($10,000 threshold; rebuttable); Me. Rev. Stat. tit. 36, § 1754-B(1-A)(C) ($10,000 threshold; rebuttable); Mich. Comp. Laws § 205.52(b)(3) ($10,000 threshold; rebuttable); Minn. Stat. § 297A.66(4a) ($10,000 threshold; rebuttable); Mo. Rev. Stat. § 144.605(2)(e)-(f) ($10,000 threshold; rebuttable); 2015 Nev. A.B. 380 ($10,000 threshold; rebuttable); N.J.S.A § 54:32B-2(i)(1) ($10,000 threshold; rebuttable); N.C. Gen. Stat. § 105.164.8(b)(3) ($10,000 threshold; rebuttable); Ohio Rev. Stat. § 5741.01(I)(2) ($10,000 threshold; rebuttable); Pennsylvania Dep’t. of Rev., Sales and Use Tax Bulletin 2011-01 (Dec. 1, 2011), http://goo.gl/Dh9Lpf (no threshold; non-rebutttable); R.I. Gen. Laws § 44-18-15(a)(2) ($5,000 threshold; rebuttable); 2015 Tenn. H.B. 644 ($10,000 threshold; rebuttable); Vt. Stat. tit. 32, § 9783(b)-(c) ($10,000 threshold; rebuttable; not take effect unless 15 states enact identical legislation); Wash. Rev. Code § 82.08.0521(1) ($10,000 threshold; rebuttable).

[4] Colo. Rev. Stat. § 39-21-112(3.5).

[5] 814 F.3d 1129 (10th Cir. 2016).

[6] Ala. Code § 40-2-11; Ky. Rev. Stat. § 139.450; La. Stat. § 47:309.1; Okla. Stat. tit. 68, § 1406.1; Pa. Code § 7213.1; R.I. Gen. Laws § 44-18.2-3; Tenn. Code § 67-6-515; Vt. Stat. tit. 32, § 9712; Wash. Rev. Code § 82-08-052. South Dakota has enacted a less-drastic requirement that sellers notify purchasers, at the time of purchase on their website, that use tax is due. See S.D. Codified Laws § 10-63-2.

[7] Ala. Admin. Code r. 810-6-2.90.03.

[8] Miss. Code R. § 35.IV.3.09; Tenn. Comp. R. & Regs. 1320-05-01-.129 (suspended pending court challenges).

[9] 830 Mass. Code Regs. 64H.1.7.

[10] Ohio Rev. Code § 5741.01(I)(2)(i).

[11] S.D. S.B. 106.

[12] Ind. Code § 6-2.5-2-1; Me. Stat. tit. 36, § 1951-B; N.D. Cent. Code § 57-40.2-02.3; Vt. Stat. tit. 32, § 9701(9)(F); Wyo. Stat. § 39-15-501.

[13] Am. Catalog Mailers Ass’n v. Krupp, Ind. Marion Superior Court, Civil Div. 1 (Commercial Court Docket 49D01-1706-PL-025964).

[14] Ohio Rev. Code § 5751.01(I); Crutchfield Corp. v. Testa. No. 2015-0386 (Ohio 2016), 2016 WL 6775765; Wash. Rev. Code § 82.04.220; Avnet, Inc. v. Dep’t of Revenue, 384 P.3d 571 (Wash. 2016) (applying B&O tax to sales made by an out-of-state company to another out-of-state company if delivery to the ultimate customer is in Washington); Steven Klein, Inc. v. Dep’t of Revenue, 357 P.3d 59 (Wash. 2015) (“Washington’s B&O tax system is extremely broad.”); Simpson Inv. Co. v. Dep’t of Revenue, 3 P.3d 741 (Wash. 2000) (applying B&O tax to receipt of dividends exempt from B&O taxation); Budget Rent-A-Car of Wash.-Or., Inc. v. Dep’t of Revenue, 500 P.2d 764 (Wash. 1972) (applying B&O tax to casual sales); Time Oil Co. v. State, 483 P.2d 628, 630 (Wash. 1971) (“[I]t is obvious that the legislature intended to impose the business and occupation tax upon virtually all business activities carried on within the state.”); Tax Comm’r v. MBNA Am. Bank, 640 S.E.2d 226 (W. Va. 2006) (upholding payment of corporate income tax by credit card companies with customers, but no employees or property, in the state).

[15] See also “The Role of Congress in State Taxation,” hearing before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on the Judiciary (testimony of Tax Foundation’s Joseph Henchman), https://goo.gl/wBohQM (“Does shipping in a returnable container versus a common carrier create nexus? Does placing an internet browser cookie on someone’s computer create nexus in that someone’s state? Does downloading an app in a hub airport while waiting between two interstate flights create nexus in the state of that hub airport? Once established, how long does nexus last? It is not just that we have different answers for different states, but also that many states supply vague or indeterminate non-answers to many of these questions.”).

[16] Joseph Henchman & Jennifer Hill, Tax Foundation Brief in Wayfair Online Sales Tax Case: SCOTUS Should Set Meaningful Limits on State Taxing Power, https://taxfoundation.org/supreme-court-brief-wayfair-internet-sales-tax.

[17] An alternative hybrid origin-sourcing proposal would charge the sales tax rate based on the seller’s location (which could be any of the state of incorporation, headquarters state, server location, or the warehouse location) and through a national agency or clearinghouse, remit the money to the buyer’s state. While appealing in its simplicity, the proposal require fundamentally restructuring how sales taxes work, confusing consumers and posing immense administrative and legal obstacles. Because the proposal would allow states to tax consumers with no minimum contacts in the state, it likely violates the Constitution’s Due Process Clause.

Share this article