Download (PDF) Fiscal Fact No. 380: Case Study #2: Property Tax Deduction for Owner-Occupied Housing

These results are part of an eleven-part series, The Economics of the Blank Slate, created to discuss the economic effects of repealing various individual tax expenditures. In these reports, TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. Foundation economists use our macroeconomic model to answer two questions lawmakers are considering:

- What effect does eliminating these expenditures have on GDP, jobs, and federal revenue?

- What would be the effect on GDP, jobs, and federal revenue if the static savings were used to finance tax cuts on a revenue neutral basis?

For an overview of the project, click here. For links to articles from the rest of the series, click here.

Key Points:

Eliminating the property tax deduction for owner-occupied housing would:

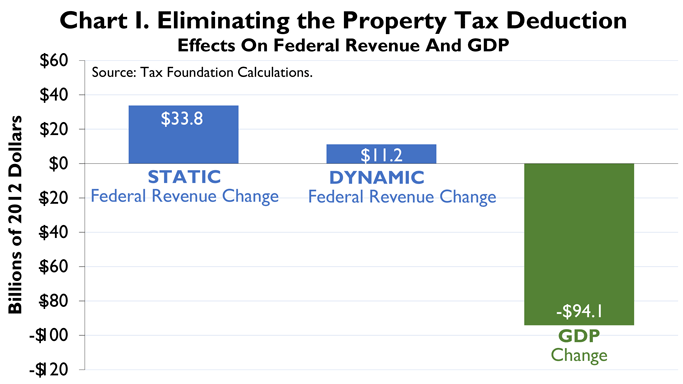

- Increase tax revenues by $34 billion on a static basis;

- Reduce GDP by $94 billion;

- Raise revenue by a smaller amount, $11 billion, on a dynamic basis;

- Reduce employment by the equivalent of approximately 216,000 full-time workers; and

- Reduce hourly wages by 0.4 percent.

Trading the static revenue gains solely for individual rate cuts would:

- Allow for an across-the-board rate cut of 3.1 percent;

- Trim the GDP decline to $42 billion per year;

- Reduce federal revenues by $10 billion on a dynamic basis;

- Increase employment by the equivalent of approximately 72,000 full-time workers; and

- Reduce hourly wages by 0.3 percent.

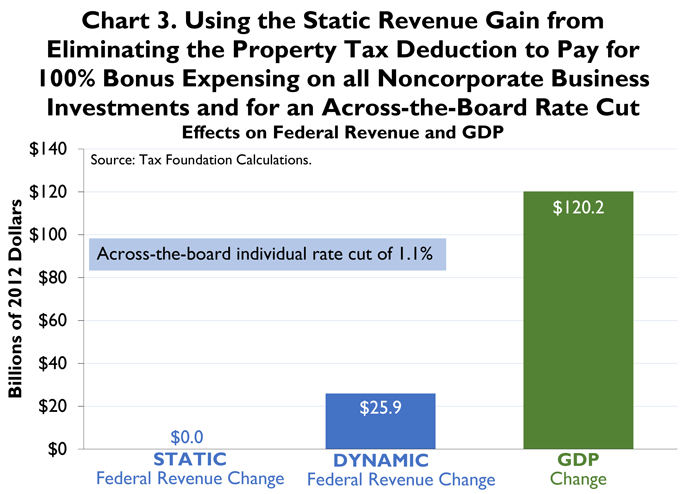

However, ending the deduction and using the static revenue gains to pay for 100 percent expensing for all non-corporate businesses and a 1.1 percent across-the-board rate cut would:

- Increase GDP by $120 billion on a dynamic basis;

- Increase federal revenues by $26 billion;

- Increase employment by the equivalent of approximately 119,000 full-time workers; and

- Increase hourly wages by 0.7 percent.

The federal individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. code permits taxpayers who itemize to claim a deduction for their local real estate (property) taxes. However, the deduction is controversial. Two criticisms are that it is mostly claimed by upper-income taxpayers, and that it softens people's opposition to high taxes and wasteful spending by local governments, because some of those taxes can be written off at the federal level. Two defenses of the deduction are that it better measures people's incomes, recognizing that some of their income has been transferred to others, and that the bulk of the local property taxes fund the public schools, increasing human capital, the cost of which could arguably be deductible, as with other capital formation. Nevertheless, the purpose of this case study is not to discuss the merits or demerits of the deduction but is simply to examine the growth effects if the deduction were repealed.

In a conventional static revenue estimate that holds the size of the economy fixed, the Tax Foundation's simulation model estimates that abolishing the federal income tax deductionA tax deduction allows taxpayers to subtract certain deductible expenses and other items to reduce how much of their income is taxed, which reduces how much tax they owe. For individuals, some deductions are available to all taxpayers, while others are reserved only for taxpayers who itemize. For businesses, most business expenses are fully and immediately deductible in the year they occur, but others, particularly for capital investment and research and development (R&D), must be deducted over time. for local real estate taxes would have raised federal revenue by $34 billion in 2012. (See Chart 1.) The Treasury estimate for 2012 is $29 billion, and the Joint Committee on Taxation revenue estimate is $25 billion.

When the unrealistic static assumption is relaxed, the Tax Foundation model predicts that ending the deduction would cause some economic harm. Losing the deduction would push some people into higher tax bracketsA tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. , and the people affected would respond to the heftier marginal tax rates by working and investing less. In addition, the higher cost of home ownership would somewhat reduce the value of the owner-occupied housing stock, either through lower home prices or the building of smaller housing units over time.[1] These incentive and price effects would make GDP 0.6 percent lower than otherwise, or about $94 billion at 2012 income levels. Because of the negative economic feedback, the estimate of the dynamic revenue gain would be $23 billion smaller than the static estimate, bringing in about $11 billion. (See Chart 2.)

If the revenue gain were used to finance an across-the-board federal income tax rate cut of 3.1 percent of the marginal tax rates,[2] the decline in GDP would be only about half as large at about $42 billion. Federal tax collections would decrease by a net $10 billion. From a growth perspective, this is not an attractive trade. Capital (even owner-occupied housing) is quite sensitive to taxes, more so than the supply of labor. Raising a property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services. can do more economic harm than may be offset by a dollar-for-dollar tax rate cut falling on wages, interest, and non-corporate business income. The trade would have to be justified on redistribution grounds.

In contrast, we also ran a dynamic simulation in which the residential property tax increase would be countered by a business property tax decrease. Most of the static revenue gain was used to increase the cost recovery of all non-corporate investments in equipment, software, non-residential structures, and residential (rental) structures. These were given 100 percent bonus expensing. This left a residual static revenue gain of $11 billion. The residual $11 billion was then used to fund a 1.1 percent reduction in income tax rates. Under this scenario, the GDP gain would increase to $120 billion, and the net federal revenue gain would be $26 billion. (See Chart 3.) This approach, adding expensing, would yield more GDP than a tax rate reduction alone.

Finally, we determined the impact of these scenarios on employment and wages. We found that simply eliminating the property tax deduction would reduce employment by the equivalent of about 216,000 full-time workers and cut hourly wages by 0.4 percent. With the rate cut offset, employment would increase by the equivalent of about 72,000 full-time employees, but wages would still be cut by 0.3 percent. With expensing of investment and a smaller rate cut, employment would be increased by the equivalent of about 119,000 full-time workers and hourly wages would rise by about 0.7 percent.

[1] In evaluating the revenue and marginal tax rate effects, we used the SOI sample of tax returns for 2008 that are the basis for our model and grossed the results up to 2012 values. In evaluating the impact on the housing stock, we took the lower JCT estimate of the tax increase for a more conservative estimate, assuming that the JCT may have a more recent estimate of the size of the current housing stock following the decline in construction after the bursting of the housing bubble.

[2] For example, the 25 percent tax rate would fall to 24.2 percent. We assume proportional cuts in all of the ordinary income tax bracket rates but no cuts in the lower tax rates on capital gains and qualified dividends.

Share this article