Key Findings

-

All OECD countries with territorial tax systems have designed provisions that seek to prevent base erosion and profit shifting by multinational corporations.

-

Designing a territorial tax systemTerritorial taxation is a system that excludes foreign earnings from a country’s domestic tax base. This is common throughout the world and is the opposite of worldwide taxation, where foreign earnings are included in the domestic tax base. requires balancing competing goals: completely exempting foreign business activity from domestic taxation, protecting the domestic corporate tax base, and creating a simple system. A system can generally only have up to two of these.

-

To complement the transition to a “territorial system,” the United States in December 2017 passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), which included new provisions applicable to U.S. multinationals including the Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI), a Base Erosion Anti Abuse Tax (BEAT), the Foreign Derived Intangible Income Deduction (FDII), and a Transition TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. .

-

Even though the goal of tax reform was to move the U.S. corporate tax system towards a “territorial” system, the new system cannot be defined as a purely territorial system.

-

Apart from the implementation of the new U.S. reforms, there are ongoing efforts in other countries and organizations including the OECD and the EU to address base erosion and profit shiftingProfit shifting is when multinational companies reduce their tax burden by moving the location of their profits from high-tax countries to low-tax jurisdictions and tax havens. .

-

OECD countries with territorial systems are now looking forward to implementing additional measures to protect their tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. . Some of the new proposals are intended to address the digital economy and the design of international tax rules.

-

The OECD has discussed a global minimum tax as an addition to other efforts to address base erosion and profit shifting.

Introduction

Most OECD countries operate what is known as a territorial or source-based tax system where foreign earnings of multinational corporations are mostly exempt from domestic taxation. Such systems allow for multinational businesses to make investments and generate earnings in multiple jurisdictions and be able to remit those earnings to domestic shareholders without extra taxation. In most cases territorial systems are based on a participation exemption that allows foreign dividends or capital gains to either be fully exempt from domestic tax liability or face a lower tax liability.

The challenge with territorial corporate income taxes is that they can be complex. The goal of a territorial tax system is to tax companies based on the location of their production, which can be difficult in today’s highly globalized world. This is because production processes stretch across numerous jurisdictions and can include transactions that are difficult to price. Companies with multinational production processes take deductions and report revenues throughout the world to allocate their profits. As such, it is often difficult to determine exactly how much profit should be taxed in a given country.

Another concern with territorial tax systems is that they can lead to base erosion. The fact that production processes span multiple tax jurisdictions leaves room for companies to take advantage of country-level differences in tax policy to allocate revenues and costs across tax jurisdictions in a way that can minimize their worldwide tax liability. Because companies do not face an additional tax on foreign profits that are repatriated to the parent company, multinational corporations would have a greater incentive to avoid domestic tax liability.

Due to these concerns, countries with territorial corporate tax systems set up rules to define how and if foreign profits are taxed, as well as rules that prevent base erosion and profit shifting. These rules include Controlled Foreign Corporation (CFC) rules, limitations on interest deductibility (thin capitalization rules), and other similar measures.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeThe rise of territorial tax systems and concurrent profit shifting behavior by multinational corporations led the G20 in 2013 to propose that the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) pursue an agenda focused on designing policies to minimize base erosion and profit shifting (the BEPS Project). Following the BEPS recommendations in 2015, many countries have adopted reforms to their territorial systems to limit some of the opportunities for tax planning by multinational corporations. In the EU, this has taken the form of the Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (ATAD).

The U.S. adopted some tenets of a territorial tax system as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in December 2017. These provisions included not only a participation exemption but also strong anti-base erosion protections with the tax on Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) and the Base Erosion Anti-Abuse Tax (BEAT).

Anti-base erosion rules and the extent to which countries exempt foreign profits from domestic taxation vary significantly from country to country. It is not clear that a “perfect” or pure territorial tax system exists. Rather, countries need to trade off among three key goals: eliminating taxes on foreign profits, protecting their tax bases, and making their tax rules as simple as possible.

The OECD work on BEPS continues with several recent proposals meant to address the challenges associated with taxing multinational digital companies. These recent options include ways to amend international tax rules to change where multinational corporations pay tax and other proposals that would layer on new anti-base erosion rules with a potential global minimum tax and a tax on base-eroding payments.

This paper reviews how the 36 OECD countries structure their territorial tax systems and construct base erosion rules. It reviews some of the changes incorporated by EU member states as part of the ATAD and the U.S. move to a territorial tax system as a result of tax reform. Finally, it briefly visits the new OECD efforts regarding the digital economy and the idea of designing a global minimum tax.

Territorial Tax Systems in the OECD

Over the last three decades, most OECD countries have shifted towards territorial tax systems and away from residence-based or “worldwide” systems.[1] The goal of many countries has been to reduce barriers to international capital flows and to increase the competitiveness of domestically headquartered multinational firms.

As part of setting up these territorial tax systems, countries constructed rules that determined when and if foreign profits would be exempt from taxation. They also put in place and strengthened rules that attempt to limit potential profit shifting.

There are basically three major aspects that define the scope of a country’s international corporate tax system.

First are what are called “participation exemptions.” Participation exemptions are what create a territorial tax system. They allow companies to exclude or deduct foreign profits that they receive from foreign subsidiaries from domestic taxable income, thus exempting those profits from domestic tax. In contrast, a worldwide system has no or few participation exemptions, and subjects those profits to domestic taxation.

Second are controlled foreign corporation (CFC) rules. The aim of these rules is to discourage or prevent domestic multinationals from using highly mobile income (interest, dividends, royalties, etc.) and certain business arrangements to avoid domestic tax liability. They work by defining what constitutes a “controlled” foreign company and when to attribute foreign income of these controlled companies to a domestic parent’s taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. .

Third are limitations on interest deductions. These rules are used to prevent domestic and foreign companies from using interest expense deductions to shift profits into low-tax jurisdictions. While these rules do not directly impact foreign profits that multinationals earn in foreign jurisdictions, they are an important part of most countries’ corporate tax systems and are aimed at preventing significant base erosion.

Participation Exemptions and Dividend Deductions

Countries enact territorial tax systems through what are called “participation exemptions” or dividend deductions. Participation exemptions eliminate the additional domestic tax on foreign income by allowing companies to either ignore foreign income in the calculation of their taxable income or to deduct foreign income when it is paid back to the domestic parent company. Participation exemptions can also apply to capital gains. Companies that sell their shares in a CFC and realize a gain may face no tax on those gains.

Some countries, such as Luxembourg, grant full exemptions for both foreign capital gains and foreign dividend income earned by domestic corporations. Other countries offer exemptions for one type of income, but not the other. Estonia, for instance, offers a full exemption for dividend income received from foreign subsidiaries (when certain requirements are met), but taxes capital gains realized from the sale of a foreign subsidiary as ordinary corporate income.

Of the 36 OECD member states, 31 countries offer some exemption or deduction for dividend income, 24 countries offer an exemption for capital gains, and 23 countries offer an exemption or deduction for both.

Participation exemptions also range from full to partial deductibility or excludability. For example, France exempts 95 percent of foreign dividend income and 88 percent of foreign capital gains. Countries providing partial exemptions often do so because it is less complex than accounting for business expenses that don’t directly correlate to physical production. Usually, companies are required to allocate overhead costs of their headquarters, such as office supplies, to foreign subsidiaries. Allocating these costs can be complex. So instead of writing rules requiring companies to allocate expenses, countries allow companies to deduct those costs domestically, but tax a small portion of their foreign profits instead.

Limitations to Participation Exemptions

While most countries have enacted participation exemptions to eliminate the domestic tax on foreign profits, these exemptions are not unlimited. Countries have a range of rules that determine whether foreign profits are subject to tax when repatriated or paid back to their domestic parent.

Many European Union (EU) member states offer exemptions only when the resident company holds at least 10 percent of the subsidiary’s share capital or voting rights for some specified period of time. France and Germany are notable exceptions, with France requiring only a 5 percent holding, and Germany unconditionally exempting 95 percent of foreign capital gains.

In the case of the United States, the new participation exemption adopted under TCJA is limited to dividends received by corporations that are 10 percent owners of foreign corporations (United States shareholders) according to the tax code. The foreign portion of the dividend is allowed as a deduction. Hybrid dividends are not able to benefit from the participation exemption. A hybrid dividend is a dividend that is treated differently for tax purposes, according to the law of two jurisdictions; for example, a dividend that can be deductible for the payor (or creditable, maybe refundable) and would be deductible when received by the payee (a U.S. corporation). Tax credits for taxes paid or accrued with respect to dividends distributed from a subsidiary in a foreign country are not allowed when a deduction for the dividend is applicable in the other country. Individual taxpayers are not eligible for the participation exemption.

Countries also limit participation exemptions and dividend deductions based on foreign subsidiaries’ location. EU member states typically limit exemptions to subsidiaries located in other EU member states or within the European Economic Area (EEA). Some countries publish a “black list” of jurisdictions where the tax regime is considered abusive and will not provide exemptions to profits earned in those jurisdictions. Others, such as Norway, impose a standard where a company needs to conduct real business activities abroad in order to qualify for a participation exemption. This directly excludes holding companies and other kinds of passive operations from receiving an exemption.

Some countries have restrictions based on the line of business a foreign subsidiary is in. For example, several countries that exempt most dividend income will not exempt profits derived from certain service-based subsidiaries such as law offices.

Controlled Foreign Corporation Rules

A common concern with moving to a territorial tax system is base erosion. Under a territorial tax system, companies no longer face an additional tax on foreign profits that are repatriated to the parent company. Because of this, multinational corporations have incentives to avoid domestic tax liability by using transactions to shift income to foreign subsidiaries in jurisdictions with lower tax rates.

Countries address this issue with anti-base erosion rules called “CFC rules.” These rules aim to discourage or prevent domestic multinationals from using highly mobile income (interest, dividends, royalties, etc.) and certain business arrangements to avoid domestic tax liability. CFC rules are designed to prevent profit shifting without penalizing foreign subsidiaries engaged in legitimate business practices.

CFC rules are not unique to countries with territorial tax systems. Prior to the Tax Cuts and Jobs act, the United States had rules to prevent companies from indefinitely deferring profits that were likely being purposefully shifted out of the domestic tax base. In the United States, CFC rules were enforced by the application of “Subpart F” rules. With the 2017 reform an additional set of rules (GILTI) was incorporated into the U.S. tax system with the intent of eliminating some of the tax benefits of shifting income outside the U.S. tax base.[2]

CFC rules generally outline policies for taxing the undistributed income of a domestic corporation’s foreign subsidiaries. This means that if a foreign subsidiary of a domestic parent corporation is deemed a CFC and subject to a country’s CFC rules, all or a portion of its profits are immediately subject to domestic tax. The income can either be taxed separately from domestic income or it can be incorporated into the taxable base of the domestic parent corporation.

For example, a British corporation may own a subsidiary located in the Cayman Islands. If the British CFC rules determine that the Cayman subsidiary is a CFC and the Cayman rate is 75 percent lower than the British rate, the Cayman operation can be considered as profit shifting, and the Cayman subsidiary’s profits then will immediately be taxed in the United Kingdom.

CFC rules are very common throughout the OECD. Only Switzerland does not have any formal CFC rules. Though some OECD countries enacted CFC rules in the 1970s, most enacted or modified their rules following the recommendations from the OECD BEPS project in 2015. However, some countries often have other more qualitative base erosion provisions that attempt to accomplish the same goal as CFC rules.

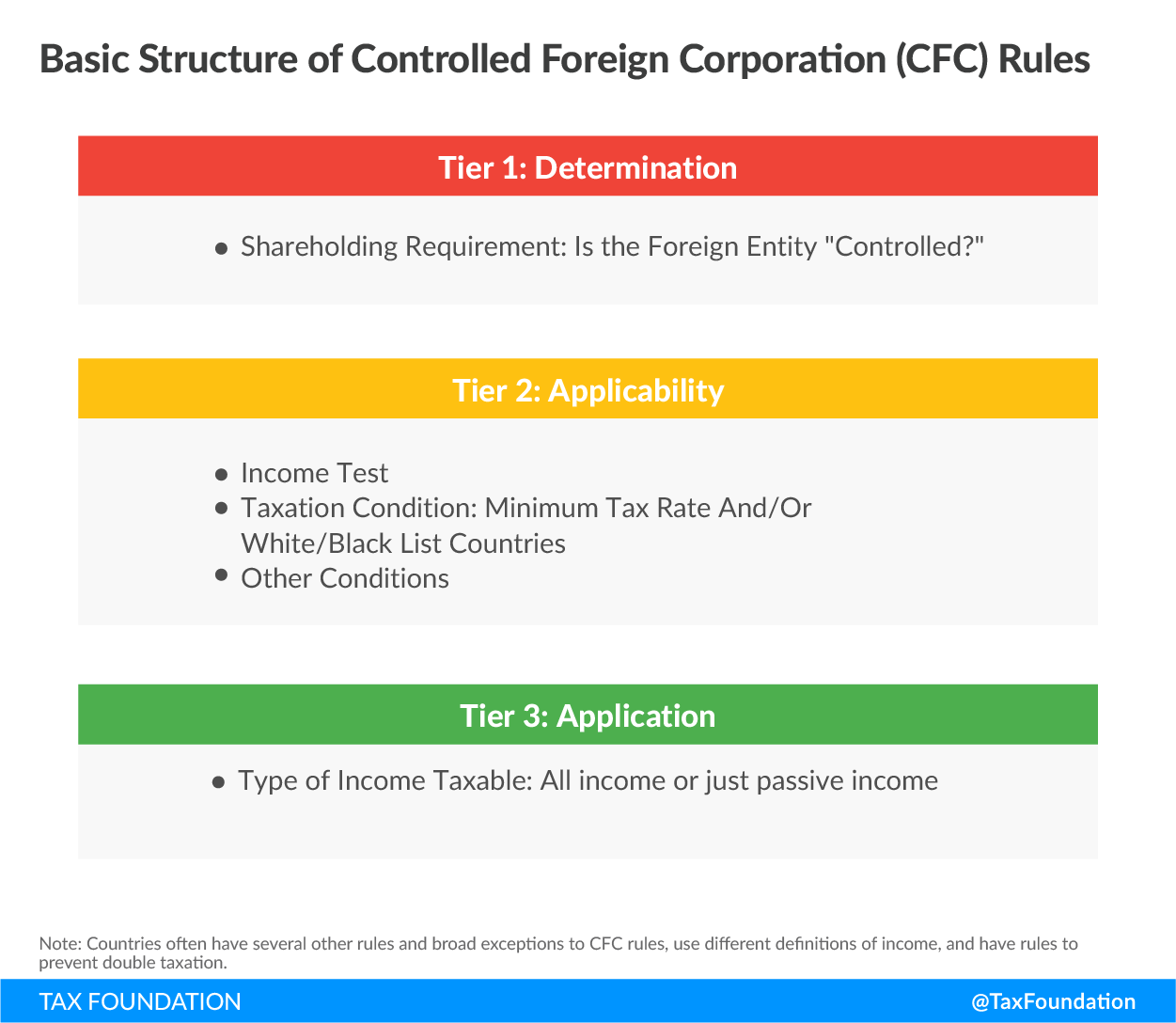

Basic Structure of CFC Rules

CFC rules, while complicated and highly variable, all follow a common outline. First, an ownership threshold or test is used to determine whether an entity is considered a CFC. Next, a second tier of standards is used to determine if the CFC is taxable in the parent company’s country. Finally, the rules determine what types of income are taxable.

Figure 1.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeTier 1: Determination

The first set of rules is meant to determine whether a foreign corporation is “controlled.” The idea is that if a foreign company isn’t controlled by a domestic corporation, the domestic corporation isn’t necessarily responsible for profit shifting that may be occurring. What constitutes control varies by country and some countries have ownership thresholds that more easily trigger CFC status than others.

The most common standard is a 50 percent ownership threshold. Twenty-nine OECD countries use this standard. This means that if one or more related corporations together own more than 50 percent of a foreign corporation’s shares, that corporation is considered a CFC. For example, if a Finnish corporation independently owned 30 percent of shares in a foreign subsidiary and two of its domestic affiliates owned another 40 percent of shares in the subsidiary, then the foreign subsidiary would be considered a CFC.

Some countries narrow the scope of CFC determination by combining these total ownership thresholds with single-ownership thresholds. Single-ownership thresholds apply to the level of ownership for a single individual or corporation. For example, the United States combines its 50 percent ownership threshold with a 10 percent single-ownership threshold. This means that a foreign entity is considered a CFC if 1) more than 50 percent of the shares are owned by a U.S. corporation and its affiliates and 2) each affiliate owns at least 10 percent. France has a similar rule, but the single-ownership threshold is 5 percent. In total, there are five OECD member states with such hybrid systems.

The United States broadened the reach of the control standard after tax reform. The 2017 tax law expanded the combined standard and the 50 and 10 percent thresholds are now not only limited to voting power of all classes of stock of a shareholder in the corporation but there is also the option to determine control using the total value of shares of all classes of stock of the foreign corporation. The test is not inclusive, and any option can determine if a corporation is considered as controlled. A set of constructive ownership rules also applies to the CFC determination in the case of the 50 percent standard.

Some countries utilize only a single-ownership test. South Korea, for example, considers a subsidiary a CFC if only more than 10 percent of its share capital is held by a single domestic corporation. In Sweden, a foreign subsidiary is considered a CFC if a single shareholder owns more than 25 percent of its shares. Of the OECD countries with CFC rules, twenty-four employ a single-ownership test.

Other countries, such as New Zealand and Australia, use an either-or-approach. In both countries a foreign entity is deemed “controlled” if either a single company owns more than 40 percent of the shares or five or fewer related entities own more than 50 percent of the shares.

Some countries use more qualitative assessments to determine CFC status. Mexico considers any foreign corporation where domestic entities have “management control” to be a CFC, and Chile considers foreign corporations to be CFCs when a domestic company has the unilateral power to alter the foreign corporation’s bylaws. New Zealand and Australia also use a qualitative control standard.

Tier 2: Applicability

While many foreign corporations might qualify as a CFC, not all will be subject to domestic taxation. There are generally two ways in which countries determine whether CFC income is taxable by domestic tax authorities.

The first way is through a “taxation condition.” This standard is aimed at preventing profit shifting to low-tax jurisdictions, or “tax havens.” The classification of tax havens is usually based on the effective corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rate levied against the CFC or a “black” or “white” list. Generally, a standard threshold is utilized to determine if the tax rate in the CFC’s country of residence encourages tax avoidance.

The threshold can either be an arbitrarily determined rate or a metric comparing the CFC’s taxation abroad to the treatment it would receive as a domestic enterprise. For instance, Mexico enforces CFC restrictions if the CFC pays an effective rate that is less than 75 percent of the Mexican statutory corporate income tax rate. Twenty-seven countries subject CFCs to regulation based on a taxation condition.

The second way in which countries determine whether CFC income is taxable is by analyzing the type of income earned by a CFC. There are two main categories that business income can fall into: active and passive. Active income arises from traditional production activities, whereas passive income comes from legal or financial activities that do not necessarily require the participation of the person who receives the income. Passive income in most countries usually includes interest, dividends, rental income, and royalty income.[3] Countries that use income tests typically tax CFCs if a majority of their revenue is derived from passive income.

Eighteen countries use the percentage of total income derived from passive sources as a benchmark to determine whether CFC rules apply to an entity. The benchmarks diverge enormously. New Zealand applies CFC rules if passive income is greater than 5 percent of total CFC income, whereas Hungary applies CFC rules if passive income is greater than 50 percent of total CFC income.

A few countries also have further conditions they use to determine whether a CFC is taxable. Some countries, like Denmark, will also apply CFC rules in cases where the foreign corporation has financial assets exceeding a determined threshold. The United Kingdom has several potential tests it uses, including length of share ownership and the foreign company’s profit margin. Other countries will only tax a CFC’s profits in the hands of its parent if the parent company owns a certain amount of the CFC’s shares. For example, Finland will only tax a CFC’s income if its domestic parent owns at least 25 percent of its shares.

Tier 3: Application

Once a country’s CFC rules determines that a company’s CFC’s income is taxable domestically, the rules then define what income is subject to tax. These rules also vary significantly and can apply to a share of passive income or both active and passive income. Of the countries with CFC rules, seventeen countries only tax passive income earned by CFCs while eighteen countries impose taxes on both active and passive income of CFCs.

Additional Rules and Exemptions

In addition to these general rules, nearly every country has exemptions that determine when a CFC may not be subject to these rules or taxation at all. For example, the EU Constitution[4] contains freedom principles conceived to facilitate business operations between members (as is the case of the freedom of movement and freedom of establishment). There are different cases where those freedoms have been limited by the application of certain EU members’ jurisdictional laws, and they have intended to tax CFC business across the EU.

As a result, the European Court of Justice issued the wholly artificial arrangements doctrine to restrict unilateral actions that limit the application of these freedoms.[5] According to this doctrine CFC taxation may limit these freedoms only when arrangements have been created with a tax avoidance purpose, the so-called “wholly artificial arrangements.” With the EU Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (ATAD) most EU countries have designed rules that exempt CFC income from taxation when they operate in other EU and European Economic Area (EEA) countries, as long as they are engaged in real economic activities. In addition to the real economic activities rule, some EU members also require that there is a signed treaty with the other member country for the CFC exemption to apply.

Non-EU countries such as Japan, Slovenia, and Korea have similar active business exemptions. Other countries, such as Finland, Sweden, and Chile, exempt CFCs if they operate in “white list,” or treaty countries. Some countries may exempt CFCs if their profits are below a de minimis threshold. Netherlands has a minimum substance safe harbor where if a company has labor costs and an office space for 24 months, the CFC profits are exempted from taxation. Besides exemptions, countries also have provisions that seek to prevent the double taxation of income that has already been taxed through a CFC rule when repatriated.

Interest Deduction Limitations

Under most tax systems throughout the world, the interest corporations pay on loans and bonds is deductible against taxable income, while interest income is taxable. It is common practice for a multinational corporation to lend itself money, by providing loans to and from subsidiaries located in foreign countries. These cross-border loans are helpful for companies to expand and make new investments in foreign markets.

However, as with other deductible expenses, interest deductions can be used to exploit cross-country differences in corporate tax systems to reduce corporate tax liabilities. Multinational corporations have an incentive to take out loans in high-tax countries, where they can take deductions, and lend from low-tax countries, where they can realize interest income, resulting in a lower worldwide tax burden.

Interest deduction rules can be seen as supplemental to CFC rules. CFC rules apply only to resident corporations whereas interest deduction limitations apply to all corporations—foreign and domestic.

To combat potential abuse of interest deductions, countries place limitations on these expenses. Thirty-three of the 36 OECD nations place some sort of formal limitation on interest expense deductions. Ireland has informal limitations on interest deductions. The only country that does not have any widely applicable limitation on interest deductions is Israel. Austria also has no official rules on interest deduction expenses, however, there are broad judicial guidelines that usually serve to regulate interest deductions. Most of the EU members modified their regimes and included an interest expense limitation rule due to the application of ATAD. In the United States, the rules governing interest deduction limitations were tightened with TCJA and a new business interest limitation rule that resembles the OECD parameters established in BEPS action 4.

Interest deduction limitations are often implemented through rules specifically targeted at multinational corporations, called thin capitalization rules.[6] Thin capitalization rules target companies whose debt levels far exceed equity. Most of these rules are designed to apply when a company has a debt-to-equity ratio beyond a predetermined threshold. Of the twenty-three OECD nations using thin capitalization rules, fourteen members employ this method. Austria generally uses the arm’s length standard since it does not have explicit thin capitalization requirements. In some cases, tax authorities also use the debt-to-equity ratio on assessments to evaluate whether interest deductions can be restricted.

A few countries with debt-to-equity-style thin capitalization rules also pair them with restrictions on interest deductions to a set percentage of income. Seventeen OECD countries with thin capitalization requirements use this rule, with Belgium, Hungary, and Turkey employing this restriction in conjunction with a debt-to-equity ratio.

In recent years, countries have introduced much broader interest deduction limitations. These limits are sometimes called “earnings stripping” rules and restrict interest deductions to a set percent of income. Twenty countries have these rules. For example, The United Kingdom limits corporate interest deductions to 30 percent of earnings before interest deductions and taxes (EBITDA). The standard was set up by the OECD in the BEPS project and made mandatory by the application of ATAD to all EU members.

Few OECD members have restrictions on interest deductibility that employ more qualitative assessments. Generally, these assessments examine the intent and fairness of intracompany loans. Specifically, the loan must be made for a clear commercial purpose and must have interest obligations similar to those that would be offered by a third party. Sweden, for example, denies deductions if the interest on the loan is taxed at less than 10 percent, if the loan does not serve a commercial purpose, and if the loan would not have been made by an independent third party. Most of the rules limiting interest deductions in the EU have recently changed or are in the process of changing since the European Council enacted the ATAD, which establishes a standard for interest deductions rules that should be implemented over the EU members.

Other Anti-Base Erosion Provisions

Though participation exemptions, CFC rules, and interest deduction limitations are the main supports for territorial tax systems and anti-base erosion policies, several countries have additional sets of rules that work as anti-base erosion policies. Many of these policies have been adopted relatively recently, and some of these new provisions were developed as part of the OECD’s BEPS project. For example, countries have started adopting country-by-country (CbC) reporting, which requires companies to report to tax authorities information such as profits, sales, number of employees, and taxes paid in each country they operate in. Countries including the United Kingdom, Australia, Germany, and the United States have also introduced some unique anti-base erosion provisions.

UK Diverted Profits Tax and IP Tax

In 2015, the UK introduced the Diverted Profits Tax (DPT), often referred to as a “Google Tax,” which is intended to target tax avoidance practices of large multinationals. This policy basically sits on top of all the other anti-base erosion rules in the UK and is meant to target specific transactions that tax authorities deemed to be abusive. The application of the tax in the United Kingdom, specifically, is complex and somewhat subjective in nature.[7] The DPT applies a 25 percent tax rate on taxable profits that are artificially diverted away from the UK tax base. In some instances, businesses have altered their structures to pay UK corporate tax to avoid having to pay DPT.[8]

More recently, in 2018 the UK introduced a separate tax targeted at intellectual property located in low-tax jurisdictions. This policy applies to any foreign company with more than ₤10 million in sales derived from intellectual property (IP) in countries with corporate tax rates below 50 percent of the UK rate. Businesses subject to the policy need to pay UK corporate tax on their IP income. Offshore income could be exempt from the tax if there is sufficient business substance in the offshore location or if the UK has a double tax treaty with the jurisdiction that includes a nondiscrimination provision.[9]

Australia Multinational Anti-Avoidance Law and Diverted Profits Tax

Australia has an additional anti-base erosion provision, titled the Multinational Anti-Avoidance Law (MAAL), which allows the Australian Taxation Office to impose penalties of up to 120 percent of the amount of avoided tax under certain circumstances. The MAAL has been in effect since 2016 and applies to significant global entities (SGEs). SGEs are defined as multinational businesses with global revenues of $1 billion AUD or more or an entity which is part of a multinational group with at least $1 billion AUD in global revenue. The MAAL penalty applies to business structures or transaction arrangements for which one of the main purposes of the structure is to gain Australian tax benefits or both an Australian and foreign tax benefit.

Australia has had a diverted profits tax in force since 2017. Like the MAAL, the Australian DPT also applies to SGEs. The DPT applies to a penalty rate of 40 percent on profits that are deemed to have been diverted from the Australian corporate tax base through arrangements that do not reflect economic substance. As in the UK, the Australian DPT is designed to be a harsh penalty for business practices that result in corporate taxes being paid at a rate lower than what the tax authority would deem appropriate or avoiding taxes altogether.

German Royalty Barrier Rule

In 2017, Germany introduced a royalty barrier rule that impacts royalties paid on intra-group transactions that result in an effective tax rate below 25 percent. The rule denies the deductibility of those payments. However, the royalty barrier does not apply when the recipient of a royalty is covered by the CFC rules.

Proposals in the United States

Over the last decade, U.S. lawmakers and academics introduced several proposals to reform the tax treatment of foreign profits of multinational corporations. Most proposals were to enact a “territorial” tax system by exempting foreign profits from domestic taxation. At the same time, these proposals would have enacted significant changes to the U.S.’s anti-base erosion rules. There were significant differences in how these proposals were ultimately designed. Ultimately, lawmakers ended up taking ideas from several proposals when designing the TCJA.

The first major proposal was from former Treasury Department analyst Harry Grubert and Rutgers economics professor Rosanne Altshuler in 2013. In their paper they proposed the creation of a minimum tax along with a move to a territorial tax system.[10] In 2014, Former Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp presented a tax reform proposal to modify the U.S. worldwide system and turn it to a territorial system. Additionally, he proposed to strengthen the anti-base erosion provisions, mainly aimed at intangible income, or income derived from intellectual property (IP).[11]

Finally, former President Obama presented a proposal in 2015 that would also have moved the U.S. to a territorial tax system and strengthen anti-base erosion rules. However, rather than introducing a participation exemption, the proposal would have introduced a minimum tax on foreign earnings and any income not subject to the minimum tax would not face any additional domestic tax.[12]

The 2017 US tax reform

In December 2017, President Donald Trump signed Public Law 115-97,[13] which enacted the first major tax reform for the United State since 1986. Along with other major changes, it moved the U.S. worldwide system towards a territorial system.

In order to move to a territorial tax system, the TCJA enacted a participation exemption. The participation exemption in the TCJA eliminated the additional tax on foreign profits of U.S. companies by giving a 100 percent deduction for the dividends received by the U.S. shareholders of those companies.[14] The deduction is applicable only for domestic corporations. To be eligible for the deduction a corporation receiving a dividend needs to:

- own 10 percent of the CFC stock (vote or value), and

- own the stock for a period of 366 days (holding period requirement).

The deduction is not available if the dividend received is able to obtain a tax benefit in the foreign country (or it is any form of hybrid dividend).

In addition to enacting the participation exemption, the TCJA enacted a set of strong protections to reduce deferral, address base erosion, and bring investments back to the country. The new set of rules protects the tax base by creating outbound provisions such as the Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) and Base Erosion Anti-Abuse Tax (BEAT), and by broadening the scope of CFC rules.

The GILTI is a new category of foreign income that includes earnings exceeding a 10 percent return on a company’s invested foreign assets.[15] It is subject to a worldwide minimum tax between 10.5 and 13.125 percent on an annual basis. The GILTI credit is limited to 80 percent and cannot be carried forward. The tax operates on the same platform of Subpart F income, but it is levied at the shareholder level and not at the corporate level. Different from what happens with subpart F calculations, the GILTI is calculated at a group level and the tax applies when there is net income and not in the case where there are losses. The GILTI acts as a minimum tax to protect the U.S. tax base. There is a serious component of complexity added to the system with the GILTI, and some U.S. taxpayers are finding their GILTI being taxed at rates much higher than 13.125.[16]

The BEAT is a tax created to combat earning stripping out of the United States. The tax is applied at a rate of 10 percent (5 percent for the year 2018) of modified taxable income minus the regular corporate tax liability (not below zero).[17] It targets multinational corporations with gross receipts of at least $500 million in the previous three taxable years, with base erosion payments to related foreign corporations that exceed 3 percent (2 percent for certain financial firms) of the total deductions taken during the fiscal year.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeAlong with the permanent features of the new system, the TCJA imposed a one-time tax created for the transition to a territorial system.[18] The idea is that when transitioning to a territorial system it is necessary to collect taxes on all the deferred income kept abroad by U.S. multinationals. The rate of the tax is 15.5 percent on liquid assets and 8 percent on illiquid assets. The tax can be paid in installments, with no consideration on repatriation of the deferred earnings of U.S. multinationals. From a policy standpoint the compliance burden has increased with the creation of the transition tax. The reason for this is that multinational companies must determine the amount of previously taxed income, and determine the amount of tax imposed on the assets abroad since 1986.

After the biggest policy change in U.S. history since 1986, it can be said that these measures mark a considerable step toward a territorial system. The new system is designed with measures to protect the tax base, address deferral, and provide incentives for corporations to bring investments back to the U.S. However, all these changes have not achieved the objective of making the system simpler than the prior regime. Additionally, the U.S. approach with the GILTI and BEAT is a much stronger approach to addressing base erosion than approaches by other countries.

The EU Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive

In January of 2016, the European Union (specifically, the EU Council[19]) presented a proposal to incorporate some base erosion measures into the EU member tax systems to level the playing field between them. The Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (ATAD) lays down rules against tax avoidance that directly affect the functioning of the EU market. By adding the new set of rules, the Council is adding a level of complexity to each member country’s tax system.

The measures to reduce the risk of base erosion and profit shifting contained in the ATAD include: [20]

- Exit taxation rules: aimed to prevent tax avoidance by the transfer of assets, or other strategies, to move a business from a country to another without paying taxes in the search for a more favorable treatment.

- CFC rules: aimed to prevent companies shifting taxable income by taxing passive income or highly mobile income from their subsidiaries in low-tax jurisdictions.

- Hybrid mismatch rules: aimed to prevent corporations from obtaining benefits from different legal and tax treatment of transactions through the legislation of different jurisdictions.

- General anti-avoidance rules: aimed to allow tax authorities to analyze the primary purpose of business arrangements.

- Interest deductibility rules: aimed to limit allowable interest deductions, avoid thin capitalization and earnings stripping, and control the use of interests to move profits from one country to another with no tax consequences.

The ATAD measures were to be implemented by January 2019, and EU countries continue to make efforts to make them part of their systems.[21]

Digital Services Taxes

Since 2018 many EU countries have been pursuing special taxes on the revenues of multinational digital firms. Though the EU has not adopted a unified approach, countries including Austria, France, the UK, and Spain and have drafted unilateral legislation to tax digital business.[22] The political goal of these proposals is to tax digital businesses in countries where they have revenues despite a lack of physical presence. Unlike other anti-base erosion provisions, these taxes target only specific lines of business including digital advertising, online marketplaces, and sales of user data from online platforms.

OECD Proposals on the Digital Economy

Following the OECD recommendations on the BEPS project in 2015, one of the major issues left mostly unaddressed was how tax policy should evolve considering the digital economy. In some ways, digital firms and businesses that earn significant income from valuable IP are able to minimize their tax liability in easier ways than manufacturing or retail businesses.

In February 2019, the OECD began a new effort on addressing the tax challenges of the digital economy that has two separate pillars.[23] Pillar 1 is aimed at redesigning international tax rules to change where multinational companies owe tax, and Pillar 2 includes proposals for a global minimum tax and a tax on base-eroding payments. Whereas many countries adopted stricter CFC rules or interest deduction limitations following the OECD’s 2015 BEPS recommendations, the Pillar 2 policies would be even stronger anti-base erosion protections.

Though the details are still being considered, the OECD has outlined the global minimum tax as an income inclusion rule similar to the U.S. tax on GILTI. Countries would be able to treat some foreign income as included in their tax base if that income is taxed below a certain minimum level. The tax on base-eroding payments would likely be structured similar to the U.S. BEAT. The OECD is working to have a finalized set of proposals by 2020.

A Territorial Tax System Requires Balancing Competing Goals

Looking at rules throughout the developed world, it is not clear that there exists a “perfect” or pure territorial tax system. This isn’t because a territorial tax system is a bad idea. Rather, it is because the taxation of corporate profits is fundamentally challenging. Thus, countries needed to make a number of trade-offs in designing their systems.

A territorial tax system basically must balance three competing goals:

- exempting foreign business activity from domestic taxation,

- protecting the domestic tax base, and

- creating simple rules.

It is only possible to accomplish two of these goals at the same time. Simplification is at odds with a policy that exempts foreign business activity from domestic tax while trying to protect the domestic tax base. Protecting the domestic tax base is at odds with a policy that exempts foreign business activity alongside simple rules. Finally, a policy that protects the domestic tax base with simple rules does not fit with exempting foreign business activity from domestic taxation.

No country in the OECD has a pure territorial tax system with no limits or restrictions.[24] However, there are systems with fewer rules than others. Switzerland, for example, is the only OECD country that has not enacted CFC rules, but it is in the midst of discussions on tax reform that may incorporate some restrictions.

In contrast, lawmakers could opt for a blunter solution to tax avoidance, such as a minimum tax on foreign profits, but they need to understand that this may have a disproportionate impact on certain industries and would not eliminate the incentive for companies to invert. Systems like this would be similar to what former President Obama proposed in 2015 or what exists in countries with broader CFC rules like Australia or New Zealand.

Even if a territorial system is a good idea, governments around the world are incorporating supplemental measures to address the problem of base erosion and profit shifting. These additional measures add layers of complexity to the application of taxation rules. Even if it is a good policy to address base erosion and profit shifting, creating complex rules is not a good policy.

Other efforts to protect the tax systems from base erosion and profit shifting are reflected in the Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive issued by the European Council, as in the new rules enacted in the United States under the TCJA that are designed to protect the tax base of U.S. multinational companies and to improve the competitiveness of the companies.

Conclusion

OECD countries have made a variety of decisions as they have worked to balance issues of exempting foreign business activity from taxation and protecting domestic tax bases. Many related policies are still developing and there is some uncertainty as to how things will evolve in the coming years. The U.S. decision to adopt a territorial tax system is certainly an improvement over having a worldwide system. However, in moving to a territorial system some of the new features created with the TCJA increased the complexity of the system. From the policy perspective it is correct to combat base erosion and profit shifting but policymakers need to keep in mind that the new rules need to be simpler. When designing new rules there is also a strong necessity to avoid increasing the compliance burden on taxpayers. All OECD nations that have moved to a territorial tax system or that had one in place had rules to prevent base erosion. Apparently, the rules were not enough and that is why there are new initiatives for international tax reform on the table, some of them taking ideas out of what the United States did with tax reform.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeAppendix

[1] Kyle Pomerleau, “Worldwide Taxation is Very Rare,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 5, 2015, https://taxfoundation.org/worldwide-taxation-very-rare/.

[2] Kyle Pomerleau, “What’s up with Being GILTI?” Tax Foundation, March 14, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/gilti-2019/. See also Daniel Bunn, “What Happens When Everyone is GILTI?” Tax Foundation, March 1, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/gilti-global-minimum-tax/.

[3] Some countries also have provisions that can redefine income as taxation passive income if abuse is suspected.

[4] Conference of the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States, “Treaty Establishing a Constitution for Europe,” Oct. 29, 2004, http://www.proyectos.cchs.csic.es/euroconstitution/library/constitution_29.10.04/part_III_EN.pdf.

[5] Lilian V. Faulhaber, “Sovereignty, Integration and Tax Avoidance in the European Union: Striking the Proper Balance,” Columbia Journal of Transnational Law 48 (May 2013): 177-241 (2010), https://ssrn.com/abstract=2272665.

[6] For more information on thin capitalization rules see “Thin Capitalisation Legislation,” OECD, August 2012, http://www.oecd.org/ctp/tax-global/5.%20thin_capitalization_background.pdf. See also Åsa Johansson, et al., “Anti-Avoidance Rules Against International Tax Planning: A Classification Economics Departments Working Papers No. 1356,” OECD, Dec. 19, 2016, https://www.oecd.org/eco/Anti-avoidance-rules-against-international-tax-planning-A-classification.pdf.

[7] For more details on the United Kingdom’s Diverted Profits Tax, see KPMG, “Diverted Profits Tax: Navigating Your Way,” September 2015, https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2015/09/diverted-profits-tax-navigating-your-way.pdf.

[8] Paul Fay, “Insight: The U.K. Diverted Profits Tax – is it Working?” Bloomberg Tax, Oct. 18, 2018, https://www.bna.com/insight-uk-diverted-n73014483427/.

[9] Hamza Ali, “Here’s the U.K. Tax Big Tech Really Needs to Worry About,” Bloomberg Tax, Oct. 30, 2018, https://www.bna.com/heres-uk-tax-n57982093373/.

[10] Harry Grubert and Rosanne Altshuler, “Fixing the System: An Analysis of Alternative Proposals for the Reform of International Tax,” Social Science Research Network, April 6, 2013, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2245128.

[11] For a detailed explanation see PwC, “2014 Camp discussion draft changes previously proposed international tax regime,” March 11, 2014. http://www.pwc.com/us/en/tax-services/publications/insights/assets/pwc-camp-draft-changes-previously-proposed-international-tax-regime.pdf.

[12] For a detailed explanation of the Obama proposal see PwC, “Obama FY 2016 Budget proposes minimum tax on foreign income and adds other significant international proposals,” Feb. 12, 2015, https://www.pwc.com/us/en/tax-services/publications/insights/assets/pwc-obama-fy-2016-budget-proposes-minimum-tax-foreign-income.pdf.

[13] “H.R.1 — An Act to provide for reconciliation pursuant to titles II and V of the concurrent resolution on the budget for fiscal year 2018,” 115th Congress (2017-2018), https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/1.

[14] Kyle Pomerleau, “A Hybrid Approach: The Treatment of Foreign Profits under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Tax Foundation, May 3, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/treatment-foreign-profits-tax-cuts-jobs-act/.

[15] Kyle Pomerleau, “What’s up with Being GILTI?”

[16] Ibid.

[17] Kyle Pomerleau, “A Hybrid Approach: The Treatment of Foreign Profits under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.”

[18]Erica York, “Evaluating the Changed Incentives for Repatriating Foreign Earnings,” Tax Foundation, Sept. 27, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-repatriation/#_ftnref3.

[19] The complete set of rules included in the Anti-Tax Avoidance Package is available at https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/business/company-tax/anti-tax-avoidance-package_en.

[20] Sebastian Dueñas and Daniel Bunn, “Tax Avoidance Rules Increase the Compliance Burden in EU Member Countries,” March 28, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/eu-tax-avoidance-rules-increase-tax-compliance-burden/.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Daniel Bunn, “A Wave of Digital Taxation,” Nov. 7, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/digital-taxation-wave/.

[23] Daniel Bunn, “Ready to Go on BEPS 2.0?” Tax Foundation, Feb. 14, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/beps-oecd-base-erosion-profit-shifting/.

[24] In 2018, the average corporate tax rate in the world was 23.03 percent and the rate among America’s largest trading partners was 23.43 percent. See Daniel Bunn, “Corporate Income Tax Rates around the World, 2018,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 27, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/publications/corporate-tax-rates-around-the-world/.

Share this article