Testimony to the Nebraska Legislature Revenue Committee

Chairman Smith and members of the Committee: My name is Joseph Henchman, and I’m vice president of state projects at the Tax Foundation. I’m pleased to have the opportunity to present this testimony on L.B. 452. While we take no position on the legislation, I hope to give a review of our research into similar policies across the country and provide our analysis of the economic effects of the taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. changes envisioned by the proposal.

I would like to provide four general comments: (1) the use of deferring tax changes, or “tax triggers,” is increasingly common to subject tax reform measures to revenue availability, and this proposal would be cautious and incremental; (2) lowering Nebraska’s out-of-line top individual and corporate tax rates would improve the state’s competitiveness and reduce individual and business tax burdens; (3) the proposed sales tax base expansion generally consists of items subject to tax in many other states; and (4) lessons to know from Kansas’s tax changes.

Summary of Proposal

The bill consists of two sets of changes: the first to take effect in 2018 and 2019; the remainder to take effect in subsequent years.

The first set of changes would eliminate Nebraska’s bottom income tax rate (currently 2.46 percent), cutting taxes for all Nebraskans with income exceeding $3,000 in taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. Taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. . The top income tax rate would also be reduced from the current 6.84 percent on income over $29,590 per year (single or married filing separately), $43,880 (head of household), or $59,180 (married filing jointly), to 6.73 percent in 2018 and 6.62 percent in 2019.[1] Personal exemptions would be reduced for those who earn more than $75,000 (single) or $150,000 (married filing jointly). The bill would also reduce the corporate income tax from the present two-rate system with a top rate of 7.81 percent to a one-rate tax of 7.58 percent in 2019 and 7.35 percent in 2020.

The second set of changes would further reduce the individual and corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. rates in subsequent years, subject to strong revenue growth. The rate reductions in both cases would occur in steps, beginning as early as tax year 2020 and continuing until the rates reach 5.99 percent, as early as tax year 2025. However, these reductions are contingent on General Fund revenue growth: if revenue growth is 3.5 percent or less, the reduction for that year is deferred until revenue growth exceeds 4.2 percent in a subsequent year.

Thus, if revenue growth is 3.5 percent or greater in each of the upcoming years, the 5.99 percent rates would take effect in tax year 2027. If revenue growth never reaches 3.5 percent, the rate reductions will not occur. If some years have greater than 3.5 percent and some years have less, the final step of the rate reductions will take place after 2025.

Revenue Triggers Have Been Successfully Used to Phase In Tax Reform Measures Incrementally, Subject to Revenue Availability

The proposal makes six of eight reductions in the top individual and corporate tax rates contingent on General Fund revenue growth of at least 3.5 percent, or 4.2 percent when this goal has not been reached the year previously. This deferring of a tax change is part of a general trend known as revenue triggers.

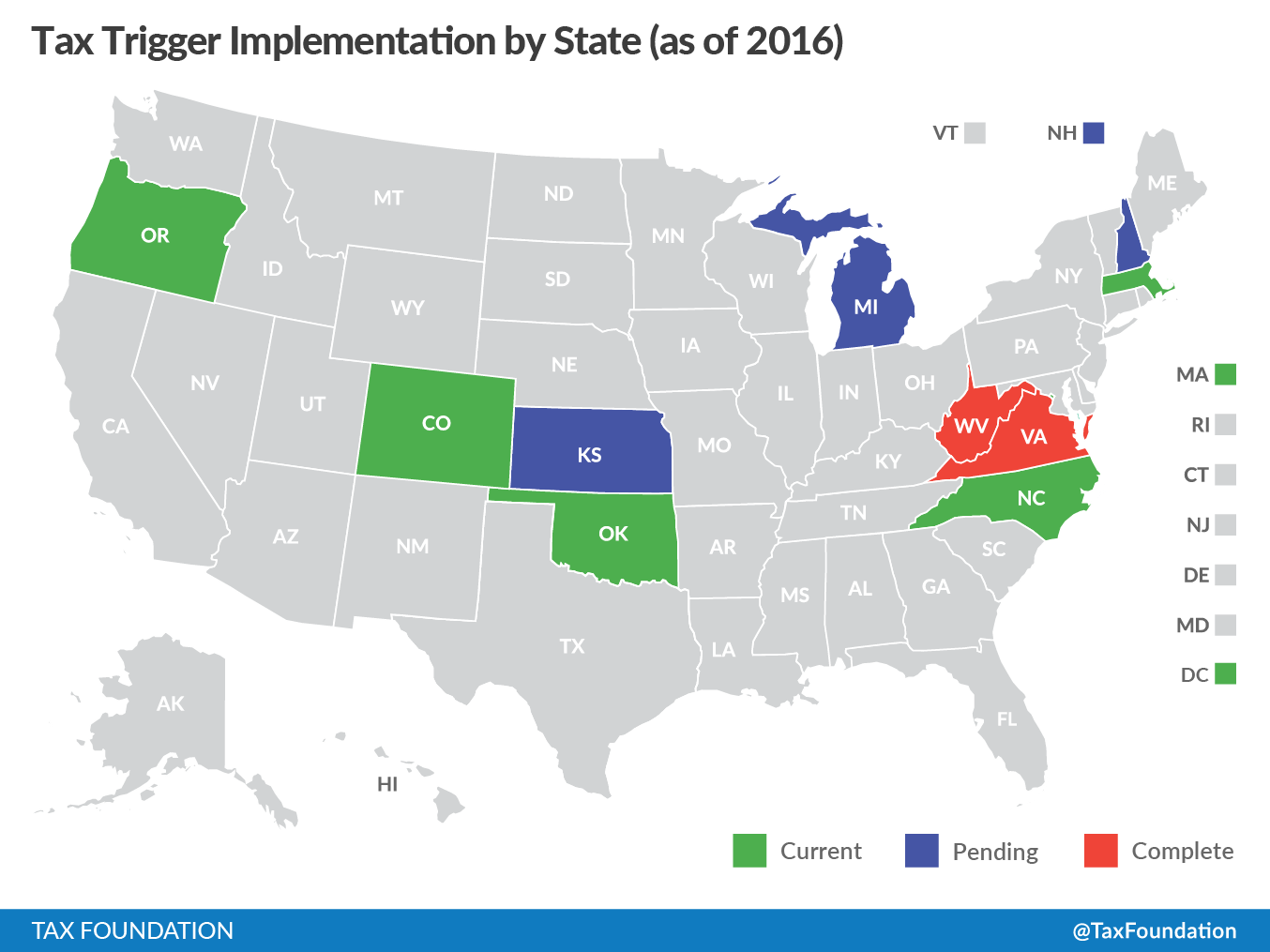

When North Carolina legislators committed to comprehensive tax reform in 2013, they broadened tax bases and eliminated exemptions to fund rate reductions—but turned to “tax triggers” to implement further rate cuts, as revenue permitted, in subsequent years. In the District of Columbia, council members linked the scope of planned tax reform to revenue availability as the reform process unfolded. Seeking a lower individual income tax rate, Massachusetts policymakers opted for a gradual phase-in of rate cuts, only when revenue growth was more than sufficient to absorb the rate change. And in West Virginia, a desire to prepare for future economic downturns was joined with efforts to make the state’s tax system more competitive through legislation providing corporate income tax rate reductions contingent on the size of the state’s rainy day fund.

In each of these cases, and many others, states turned to triggers as a way to implement or phase in tax rate reductions or other tax reform measures as revenues permitted. Tax triggers are a new take on an old concept: contingent enactment of a legislative provision. States have long relied upon bills with contingent enactment clauses, providing that certain features of new legislation shall only be operative if certain conditions are met. Tax triggers build on this model, making tax reform measures contingent on state revenues meeting or exceeding established targets.

Well-designed triggers ensure that benchmarks reflect meaningful revenue growth, rather than capturing a rebound from a year of weak revenues or the effects of inflation. They also avoid undue time constraints which can derail, rather than delay, the implementation of a program of contingent reforms. When properly constructed, tax triggers serve as a valuable mechanism for implementing responsible tax reform.

Benchmarks vary greatly across states (see table on following page). Some states rely on year-to-year revenue changes, while others establish baselines. Some devote surplus revenues to tax relief, while others set revenue growth limitations. Several use projected revenue, while others rely upon prior-year collection figures. A few tie triggers to specific years, while others leave them open-ended. Some account for inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. , while others employ triggers pegged to nominal values. The mechanisms states employ to implement tax reforms once triggered are also various: many states institute a schedule of specified reductions, others promulgate rate reductions by formula, while still others utilize credits to return surplus revenues to taxpayers.

| State | Tax | Benchmarks | Method | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CO |

PIT |

Revenue exceeds inflation + pop. growth + excess revenue cap |

Refund |

Current |

|

DC |

PIT |

Mid-year revenue estimate exceeds initial revenue estimate |

Schedule |

Current |

|

|

CIT |

Mid-year revenue estimate exceeds initial revenue estimate |

Schedule |

Current |

|

|

Mid-year revenue estimate exceeds initial revenue estimate |

Schedule |

Current |

|

|

KS |

PIT |

2.5% year-over-year revenue growth |

Formula |

Pending |

|

|

CIT Surtax |

2.5% year-over-year revenue growth (after PIT repeal) |

Formula |

Pending |

|

|

CIT |

2.5% year-over-year revenue growth (after surtaxes equalized) |

Formula |

Pending |

|

MA |

PIT |

2.5% inflation-adjusted year-over-year revenue growth |

Schedule |

Current |

|

MI |

PIT |

Inflation-adjusted revenue growth (statutory proportion) |

Formula |

Pending |

|

MO |

PIT |

GF revenue exceeds highest of past 3 years by $150M |

Schedule |

Pending |

|

NH |

CIT |

Combined GF & education trust fund revenue exceeds $4.64B |

Schedule |

Pending |

|

|

VAT |

Combined GF & education trust fund revenue exceeds $4.64B |

Schedule |

Pending |

|

NC |

CIT |

Revenue exceeds statutory benchmarks ($20.2B in 2015 & $20.975B in 2016) |

Schedule |

Current |

|

OK |

PIT |

Projections adequate to reduce rates on revenue-neutral basis |

Schedule |

Current |

|

OR |

PIT |

Revenue exceeds projections by at least 2% |

Refund |

Current |

|

VA |

Fuel Tax |

Absence of federal remote sales tax authority by given date |

Schedule |

Complete |

|

WV |

CIT |

Rainy day fund at 10% of budgeted GF revenue |

Schedule |

Complete |

The successful and broadly supported tax triggers approved by the District of Columbia may prove especially instructive for Nebraska.[2] D.C. essentially collapsed fiscally in the 1990s and the recovery from that experience has resulted in a strong set of financial safeguards and fiscally cautious government officials, determined to preserve a good credit rating and a strong rainy day fund. In 2014, the fiscally cautious D.C. Council used triggers to implement the recommendations of a tax competitiveness commission to reduce individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. rates across multiple brackets, cut the corporate tax rate, raise the estate taxAn estate tax is imposed on the net value of an individual’s taxable estate, after any exclusions or credits, at the time of death. The tax is paid by the estate itself before assets are distributed to heirs. threshold, and increase the standard deduction and personal exemption. The package was broken into 26 discrete parts and the implementing statute directs officials to ascertain each February how much revenue growth exceeds the revenue projected in the budget when passed. Elements of the tax reform package are implemented, in order, as structural revenue growth permits. To date, the first 15 elements have been enacted into law, with the remaining 11 dependent on future revenue growth. For example, if (as seems possible) this February D.C. projects revenue growth of at least $200 million above the original budget figure, all the remaining elements of the package will become law as of tax year 2018.

The relatively lengthy time frame of implementation (six years), the relatively high level of revenue growth required for the trigger (3.5 percent), and the relatively modest level of tax reduction (reducing the income tax rate overall by 12 percent, from 6.84 percent to 5.99 percent, and the corporate rate overall by 23 percent, from 7.81 percent to 5.99 percent) combine to make the proposed Nebraska revenue trigger very cautious and incremental compared to revenue triggers or tax cuts adopted by other states.

Lowering Nebraska’s Top Individual & Corporate Income Tax Rates Would Enhance Competitiveness, Eliminate the “Sticker Shock” of the State’s High Tax Rates, and Reduce Individual and Business Tax Burdens

Nebraska’s top income and corporate tax rates are high for the region and for the revenue they collect. These rates cause “sticker shock” for recruiting talent to come to Nebraska and retaining talent to stay in Nebraska. Outward net interstate migration is not just anecdotal; it is supported by available data. While Nebraska’s state and local tax collections ($4,653 per capita, 17th highest) are similar to its neighbors Colorado ($4,339 per capita, 23rd highest) and Kansas ($4,457, 21st highest), it does so with much higher tax rates.

The individual income tax was first adopted in 1968 and currently consists of four tax brackets with graduated rates, meaning that taxable income above each threshold (after subtracting deductions and a personal exemption credit) is taxed at progressively higher rates. The state’s individual income tax code is currently very progressive, with taxpayers with federal adjusted gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total pre-tax earnings from wages, tips, investments, interest, and other forms of income and is also referred to as “gross pay.” For businesses, gross income is total revenue minus cost of goods sold and is also known as “gross profit” or “gross margin.” less than $50,000 incurring less than 10 percent of all liability.

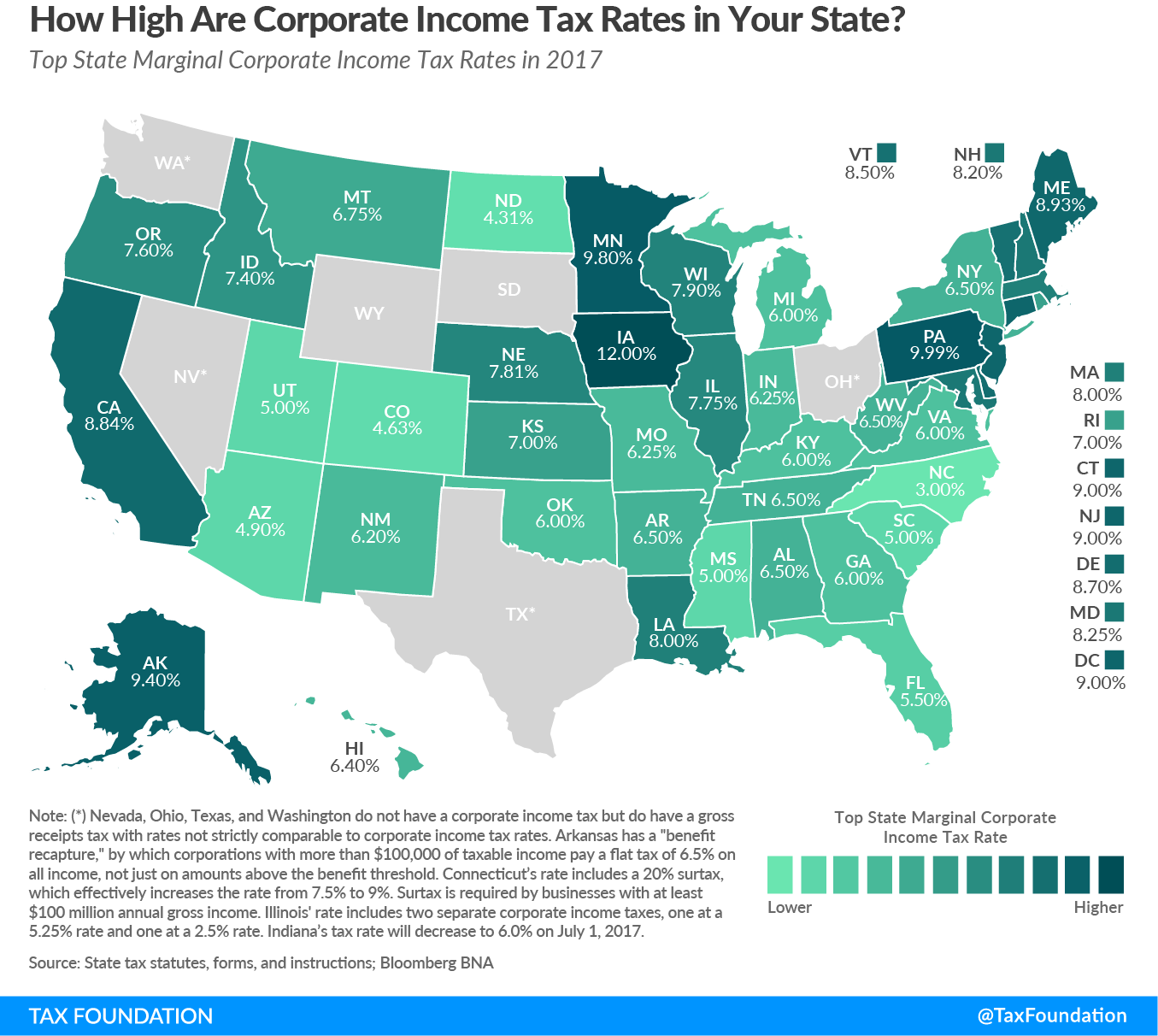

The corporate tax rate is two-bracket, with a top rate of 7.81 percent, much higher than Colorado’s 4.63 percent, Kansas’s 7 percent, Missouri’s 6.25 percent, Oklahoma’s 6 percent, and South Dakota and Wyoming (both zero) (see map on next page).

Despite this significantly higher rate, Nebraska collects just $163 per capita from this tax, compared to Colorado’s $134, Kansas’s $114, Missouri’s $59, and Oklahoma’s $102. Both research and anecdotal evidence suggest that Nebraska’s corporate income tax is porous because of heavy incentive use, ironically adopted to counter the state’s high tax rate.

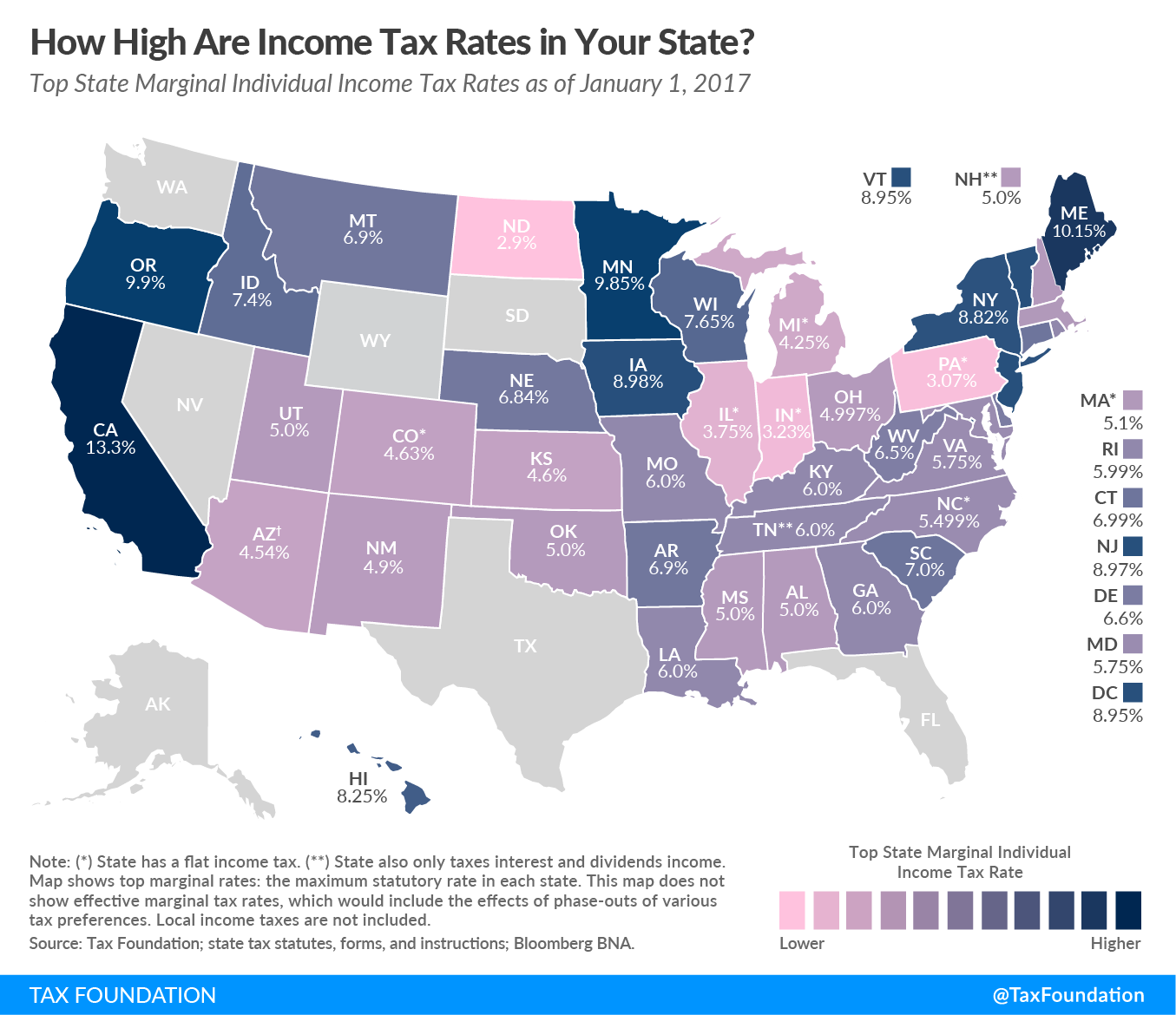

Nebraska’s top individual tax rates are one of the highest in the region (see map next page) and kick in at a relatively low level of income. Two neighboring states—South Dakota and Wyoming—forego individual income taxes altogether. Another (Colorado) imposes a single-rate income tax, while Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri all impose graduated-rate taxes like Nebraska. Only Iowa imposes a higher top marginal rate (8.98 percent), and the burden of Iowa’s high rate is mitigated somewhat by the state’s atypical allowance of a deduction for federal income taxes paid. As Nebraska grows and diversifies its economy, many prospective employees will have income levels above the top tax bracket, so the comparison to other states in the region and nationally is important for relocation decisions.

Structurally, Nebraska’s income taxes largely hew to the national average, having improved with the recent adoption of inflation-indexing of brackets. This avoids a phenomenon known as “bracket creep,” where progressively more income falls under higher brackets as time passes. Nevertheless, by virtue of the decisions of some neighboring states to levy a low, flat rate or to forego individual income taxes altogether, Nebraska faces stiff regional competition on the individual income tax component of our State Business Tax Climate Index, a comparative measure of tax structure.

Excessive taxes on income are generally less desirable than taxes on consumption because they discourage wealth creation. In a comprehensive review of international econometric tax studies, Arnold et al. (2011) found that individual income taxes are among the most detrimental to economic growth, outstripped only by corporate income taxes. The authors found that consumption and property taxes are the least harmful.

The economic literature on graduated-rate income taxes is particularly unfavorable. The Arnold et al. study concluded that reductions in top marginal rates would be beneficial to long-term growth, and Mullen and Williams (1994) found that higher marginal tax rates reduce gross state product growth. This finding even adjusts for the overall tax burden of the state, lending credence to the precept of broad bases and low rates.

| State | Individual Income Tax Component Ranking | Corporate Income Tax Component Ranking |

|---|---|---|

|

Nebraska |

24th |

29th |

|

Colorado |

16th |

18th |

|

Iowa |

33rd |

47th |

|

Kansas |

18th |

39th |

|

Missouri |

28th |

5th |

|

South Dakota |

1st |

1st |

|

Wyoming |

1st |

1st |

On the margin, graduated-rate individual income taxes increase the cost of labor, as higher rates at higher levels of income reduce the incentive for employees to work additional hours or invest in efforts to seek a higher wage position. Consequently, complex, poorly-designed tax systems that extract an inordinate amount of tax revenue reduce both the quantity and quality of the labor pool. This is consistent with the findings of Wasylenko and McGuire (1985), who found that individual income taxes affect businesses indirectly by influencing the location decisions of individuals.

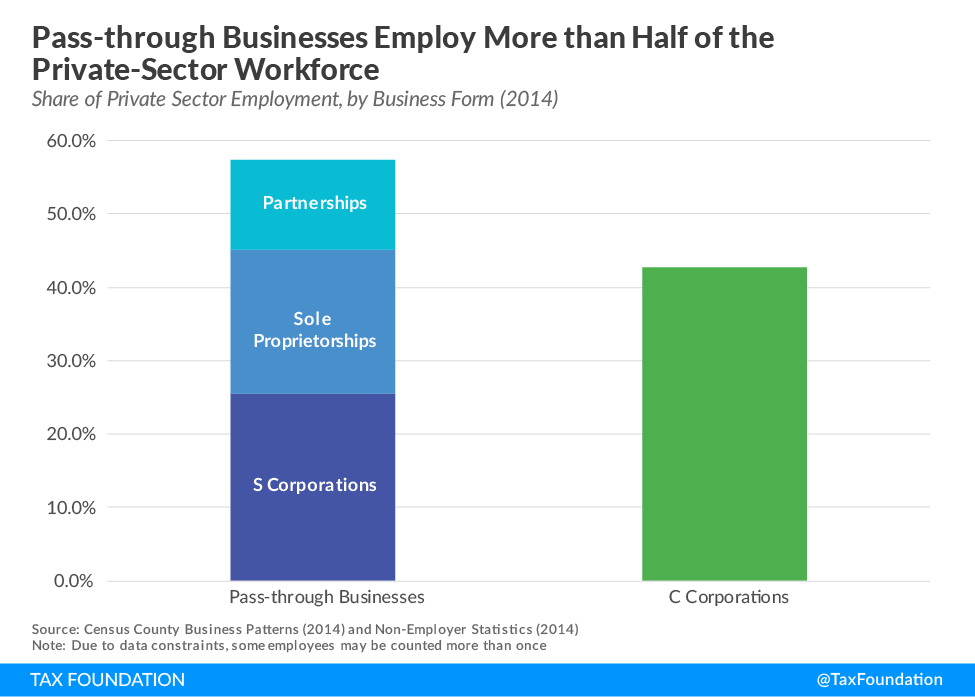

Furthermore, because S corporations, partnerships, sole proprietorships, and limited liability corporations (LLCs) remit their income tax payments through the individual income tax, the individual income tax code matters to the majority of Nebraska businesses. These businesses, known as pass-through entities, pay the individual income tax in lieu of the corporate income tax because earnings “pass through” to the income tax form of the owners or shareholders rather than being remitted by the business entity itself. Nationally, pass-throughs employ most of the private-sector workforce (see chart).

The explosive growth of pass-through businesses is a new phenomenon unanticipated by those who designed the 1967 tax code. Meanwhile, the individual income tax’s above-average rates cut into take-home pay and make the state less attractive for creating and retaining jobs. However unfairly, Midwestern states must often overcome geographic and cultural biases to land corporate relocations and attract top talent, making considerations like a competitive tax code all the more important. A modern individual income tax would recognize the impact of the tax on many of Nebraska’s small and midsized businesses, and seek greater simplicity and more competitive rates for all payers.

The Proposed Sales TaxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. Base Expansion Generally Consists of Items Subject to Tax in Many Other States

Sales tax rates are talked about frequently, but policymakers spend less time focused on sales tax bases—the basket of transactions that the sales tax applies to in a given state. That’s a shame, because there are three big problems with sales tax bases today, and policymakers have an opportunity to fix these issues.

Public finance experts generally agree that a properly-structured retail sales tax should apply to all final consumption so that you have a broad base and can levy a low rate. However, in practice most states have sales taxes that fall short of this ideal on three counts: (1) they do not tax services; (2) they exempt many final consumer goods that should be taxed; and (3) they tax business-to-business transactions that should be exempt. This proposal primarily seeks to address part of point (1) but while also addressing point (3).

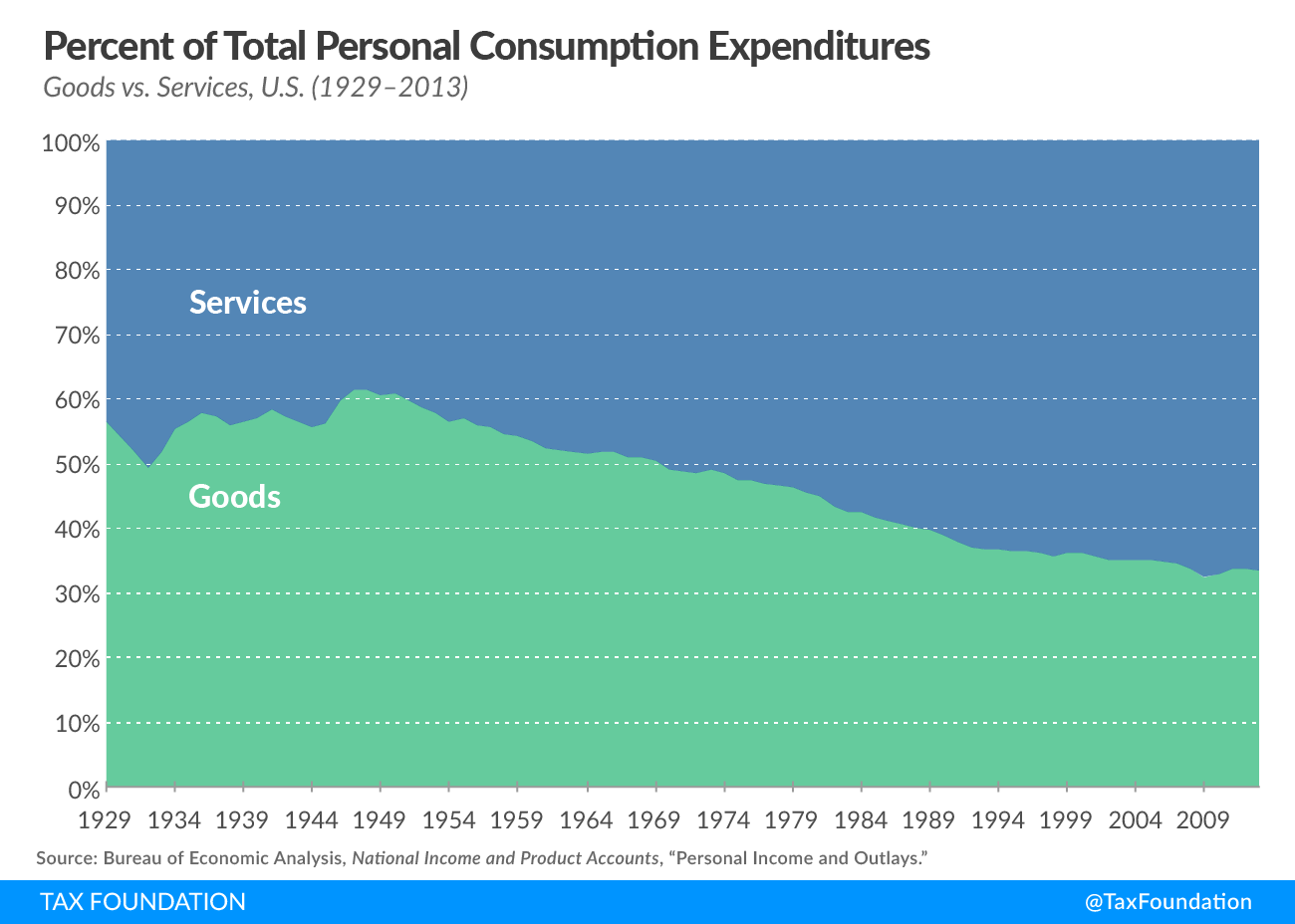

Most states do not comprehensively tax services as an accident of history. The first sales tax was enacted in Mississippi in 1930 as a reaction to falling property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services. revenues during the Great Depression. At the time, the consumer economy was predominantly transactions of goods. As a result, when the drafters wrote the sales tax statute, it only applied to transactions of tangible personal property, the goods sector. Forty-four states and D.C. followed Mississippi in enacting sales taxes in the following decades, and all but three (Hawaii, New Mexico, and South Dakota) for the most part adopted a goods-only tax structure.

This was a sufficiently broad base for a few decades, but since then the American economy has transformed to include far more services. Services now represent approximately two-thirds of consumption, and largely go untaxed by state sales taxes.

This has resulted in upward pressure on sales tax rates over time as the sales tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. continues to narrow and sales taxes bring in less revenue as a percentage of the economy. The proper solution is to broaden the sales tax base to include services, and use the revenue from that base broadening to lower the sales tax rate, or the rates of other more economically-damaging taxes.

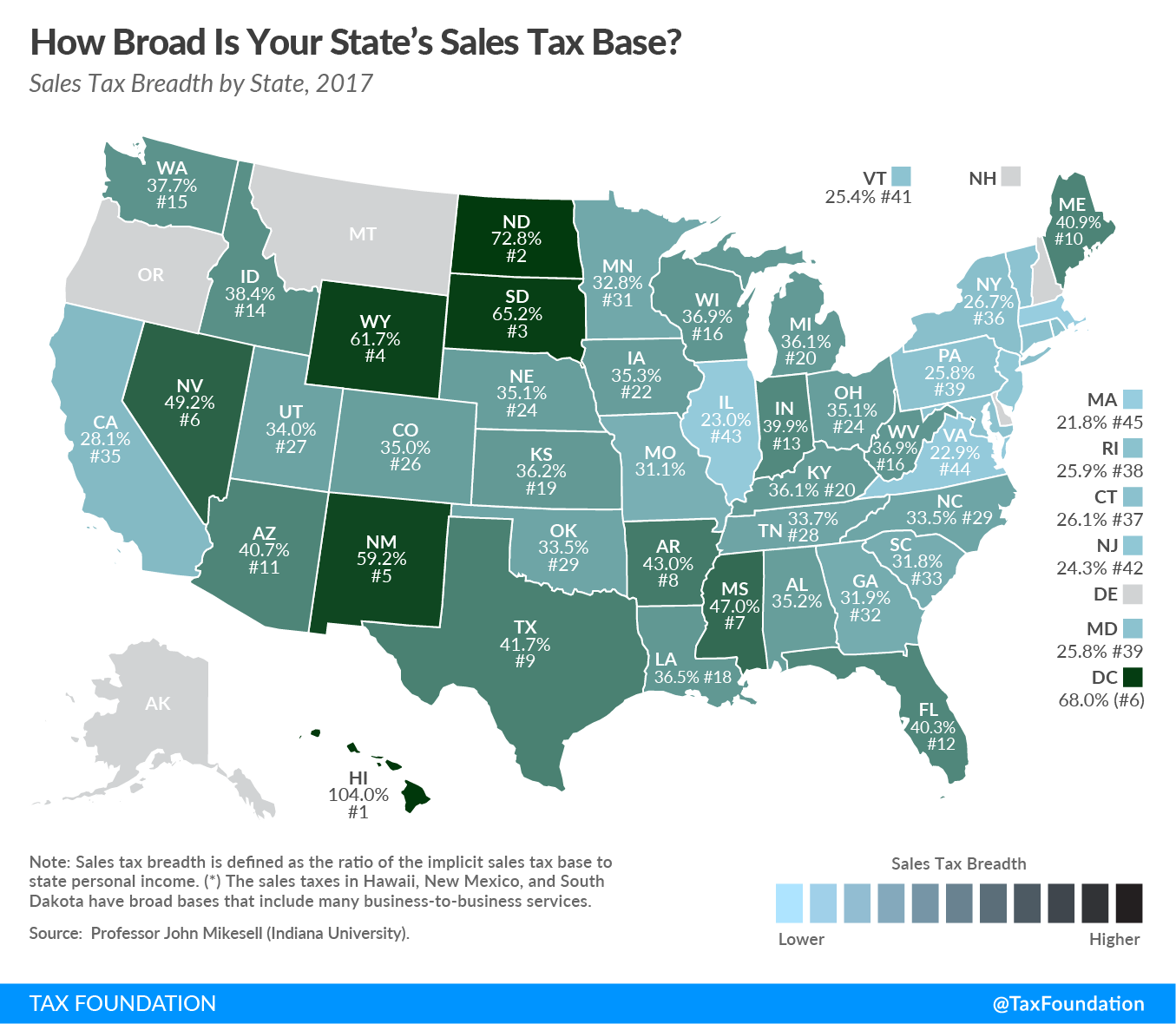

Some states have moved in this direction relatively recently, but none in a comprehensive way that changes the default treatment of services. Most states still have a default of taxing all goods unless they have an enumerated exemption, and a default of taxing no services unless they are enumerated as taxable. Nebraska is no exception; the base of the state’s sales tax is equivalent to about 35 percent of personal consumption, about average among the states but lower than several of its neighbors.

In the process of making final goods and services, businesses will often buy raw materials from each other to create products. These business inputs, or business-to-business transactions, are not final consumption, and so should not be taxed by the sales tax.

When states do tax business inputs, the costs of those taxes cascade, or “pyramid” down the production chain and embed themselves in the final price of the consumer product. Consumers end up paying the tax in the form of higher prices — they just do so in a nontransparent way. Taxing business inputs disproportionately harms industries with long production chains, and consequently can encourage vertical integration for tax reasons even if it makes no business sense. If states were to fix these three problems, they would have not only a broad-based but a “right-sized” sales tax system that taxes each dollar of consumption once and only once. This would result in stable revenue, and would allow for a low rate that brings in ample funding for government services.

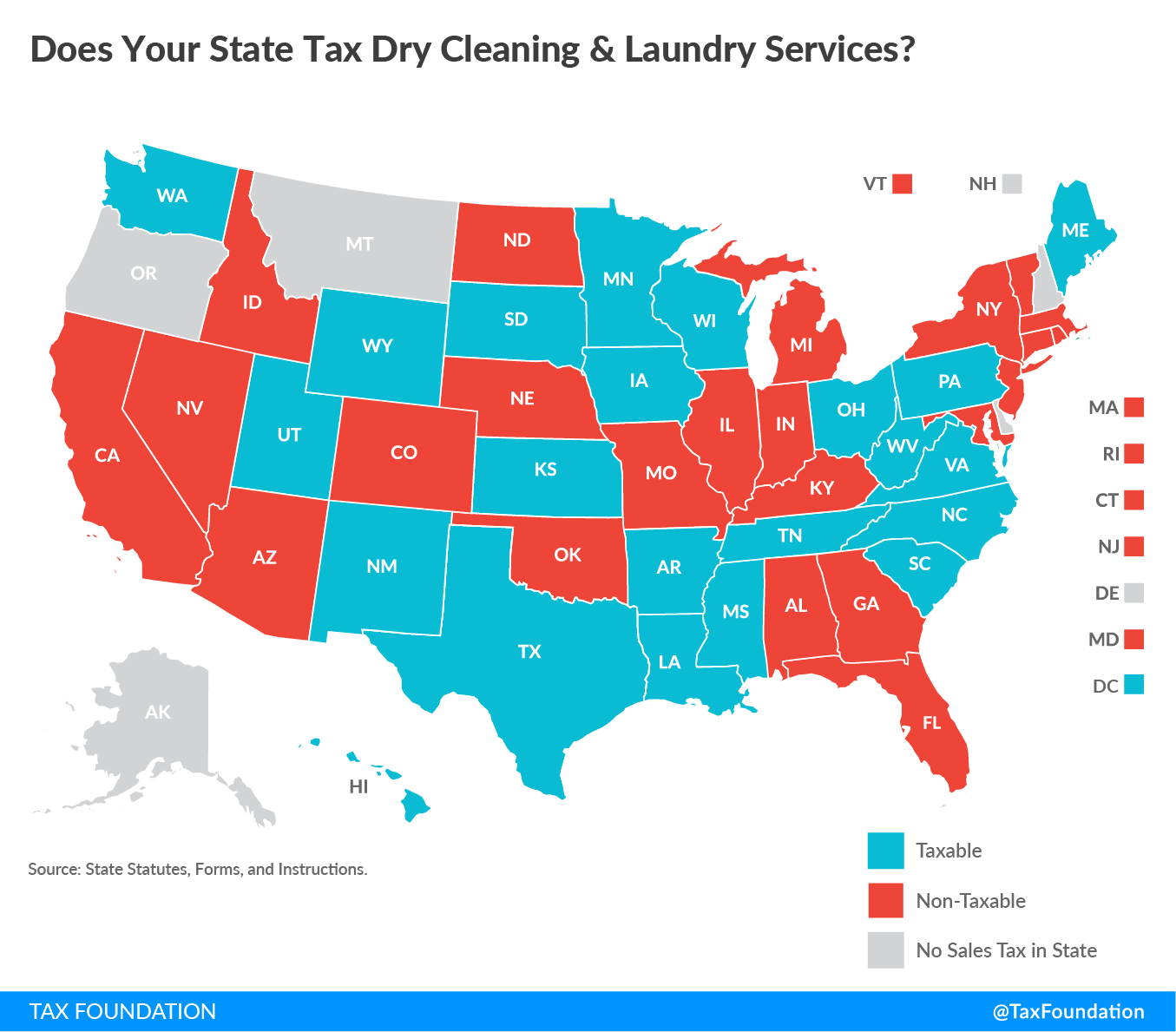

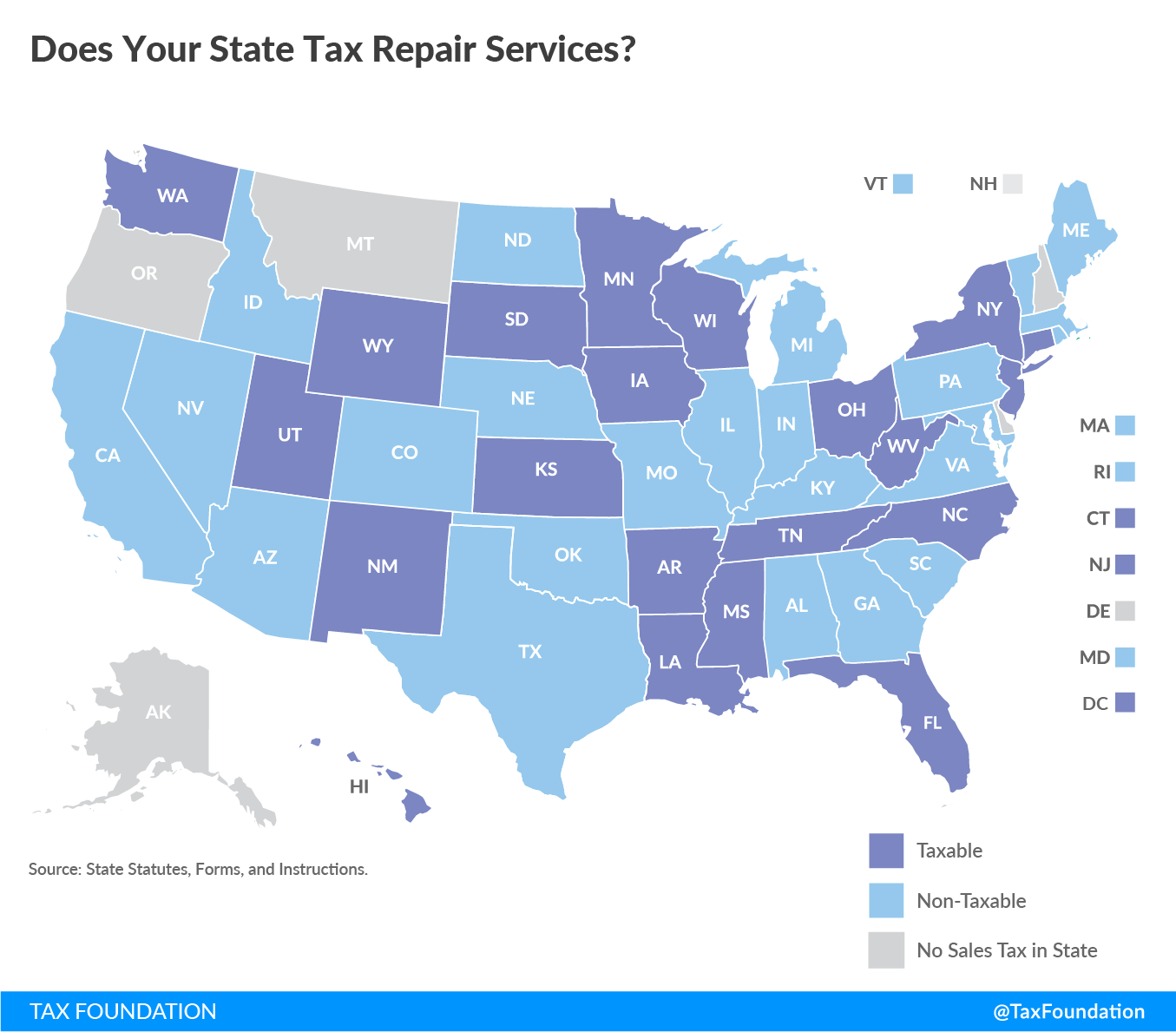

This proposal would expand the sales tax to twelve listed services, all but one of which (lottery tickets) are taxed by at least four other states. Eight of the twelve listed services are taxed by at least two of Nebraska’s neighboring states (the exceptions are tattooing, for-hire transportation, moving services, and lottery tickets). None of them are primarily business inputs, comporting with a well-designed sales tax that avoids pyramiding.

Several of the services, such as dry cleaning/laundry services and repair services, are taxed by many states (see maps).

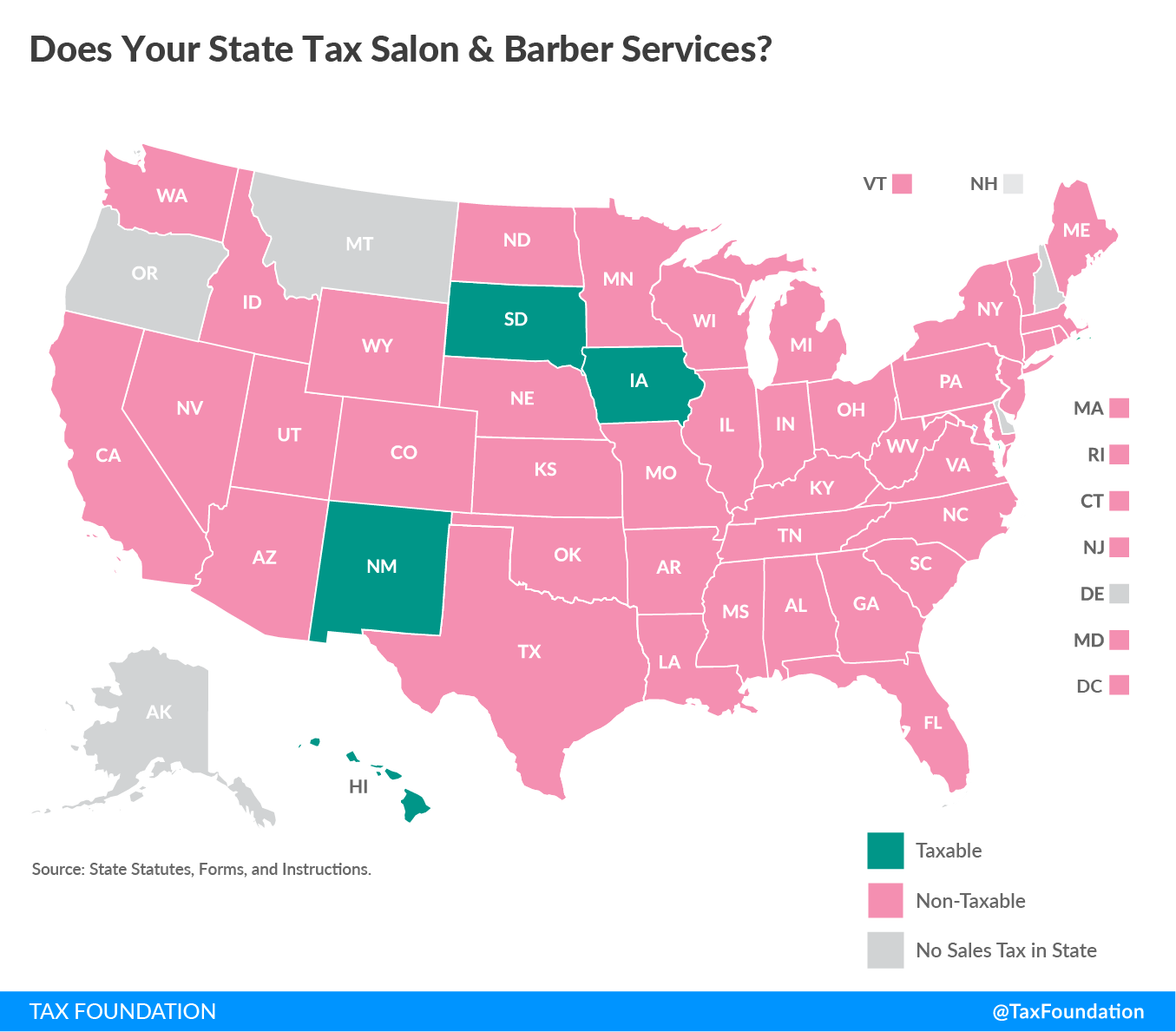

Even a service not taxed by many states, such as salon and barber services, is still taxed by two of Nebraska’s neighbors (see map).

While large-scale sales tax expansion will likely be a hot button issue in state tax policy in the years to come, this bill’s suggested expansion is modest.

Kansas Narrowed Its Tax Base with a Costly Pass-Through Exemption, and Subsequently Drained Its Rainy Day Fund, Raised Other Taxes, and Wrecked Its Credit Rating Rather than Repeal It

Nebraska’s Proposal Would Reduce the Top Tax Rate by Only 3 Percent Immediately and by 12 Percent by 2025 Only if Revenue Growth is Strong; Kansas Reduced Its Rate by 24 Percent Immediately Regardless of the Revenue Situation

In 2012, Kansas enacted a tax cut package that reduced income tax rates immediately by 24 percent (from 6.45 percent to 4.9 percent) and ultimately by 40 percent (to a goal of 3.9 percent; the rate is currently 4.6 percent) while completely eliminating income tax on pass-through entities like LLCs, S corps, partnerships, farms, and sole proprietorships.[3] At the time, we at the Tax Foundation warned that the pass-through exemption did not have good economic justification and would “encourage economically inefficient, though tax-reducing” restructuring activity. We also warned that the “tax reductions, while producing positive economic benefits, would cost revenue and ultimately need to be paid for either by cutting spending or increasing taxes elsewhere.” I was quoted saying that Kansas’s tax change was the worst tax change adopted by any state that year, and that the pass-through carveout had no place in a properly structured tax system.

In 2013, revenue dropped by $700 million ($300 million more than predicted). Spending that year was only cut $150 million. These numbers are quite large for a $6 billion general revenue fund. The state delayed a planned cut to the sales tax, weakened the generosity of itemized deductions, and drew down reserves to make ends meet. FY 2015 had a significant cash deficit, masked by draining the rainy day fund and beginning balances, and helped by very slow spending growth (only 1.1 percent from the previous year). At the beginning of FY 2016, budget deficits widened sufficiently and spending remained adequately high that hikes to other taxes were necessary to make the budget balance. The state hiked the sales tax rate from 6.15 percent to 6.5 percent, giving the state the 8th highest sales tax in the country. The state hiked the cigarette tax rate from 79 cents per pack to $1.29 per pack. A new tax was placed on vapor products (e-cigarettes). The state also eliminated many deductions in the individual income tax, and created a one-time tax amnesty program. Governor Brownback’s 2017 budget proposal for Kansas includes a further $1 cigarette tax increase, which, for a state that borders Missouri, is in my view untenable (Missouri levies a 17-cent per pack tax). This proposal is joined by a plan to securitize funds from the tobacco Master Settlement Agreement, which would dry up a future revenue stream to solve this year’s budget issues. We do not anticipate that these changes will restore sustainability to the state’s fiscal system in the long term.

My judgment, which is shared by my colleagues, is that the pass-through exemption is an important reason for Kansas’s revenue underperformance, and a carveout which deserves reexamination. When the exemption was passed in 2012, it was projected that 191,000 entities would take advantage of the provision. As more and more people have realized the very sizable tax advantage of being a pass-through entity in Kansas, the latest tally (2015) on that number has grown to 393,814 claimants, over twice as many as anticipated. The foregone revenue from the carveout is around $250 million to $300 million per year. It is important to note here that while decreasing taxes is generally associated with greater economic growth, the pass-through carveout is primarily incentivizing tax avoidance, not job creation. Exempting pass-through income substantially narrowed the tax base of that instrument, and in a haphazard way.

While some exaggerate the Kansas lesson to be one of never-cut-taxes-ever, ignoring successful recent state tax reforms as in Indiana, the District of Columbia, New York, Utah, and North Carolina, the real lesson of Kansas is to not be reckless.

Needless to say, the proposal before you bears no relation to the Kansas experiment. The proposal does not exclude pass-through income from the income tax, and top tax rate reduction is only 3 percent immediately and only 12 percent by 2025 at the earliest as opposed to 24 percent immediately in Kansas. Kansas’s reductions were implemented without any consideration as to revenue growth, while most of the proposal before you does not take effect unless revenue growth is strong. This proposal is about as opposite to reckless as you can get while still resolving to address one of the largest weaknesses in Nebraska’s tax code.

Conclusion

If the provisions of this bill were fully in effect last year, Nebraska’s rank on our State Business Tax Climate Index would have been 20th instead of 25th.

Nebraska has many strengths: an enviable employment rate, a fiscally responsible state government, good transportation infrastructure, a diverse array of successful businesses, and a deserved reputation for honesty and hard work.

Beneath this success are many worries: the future of agricultural prices, the outward migration of young people and retirees, the cultural perception of the Plains states, and heavy reliance on tax incentives to counter high tax rates. Addressing these concerns requires a number of solutions, including pro-growth tax reform. A strong tax system can overcome perceived weaknesses in other areas. For example, some sectors of Nebraska’s economy are much larger (agriculture, manufacturing, transportation, finance/insurance) than in other states, but other sectors are much smaller (IT, education, research, real estate, entertainment, accommodation/tourism) than in other states. In our conversations with Nebraska stakeholders and site selection experts, as well as our review of economic and tax data, the state’s high top individual tax rate and uncompetitive corporate tax rate remain obstacles.

Creating sound tax policy is more than a question of how much revenue should be raised. Some taxes are more damaging to the economy than others. We hope that the information we provide can be helpful as legislators determine how to ensure Nebraska is the place where investment, entrepreneurs, and talented individuals go in the years ahead.

[1] For some very high-income taxpayers, Nebraska’s top tax rate is in practice higher than other states with comparable rates because Nebraska is one of two states with an income recapture provision (New York is the other), which removes the benefit of lower tax bracketsA tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. in the tax table for high-income earners.

[2] For a detailed description of each state’s revenue trigger and how each has fared, see our report on the topic, “Designing Tax Triggers: Lessons from the States,” https://t.co/zA8aJG8fod.

[3] Technically, all income reported on federal income tax Schedules C, E, and F.