Key Findings

- A potential Nebraska ballot initiative, known as the EPIC Option, would eliminate all income, property, and inheritance taxes and replace them with a statewide consumption taxA consumption tax is typically levied on the purchase of goods or services and is paid directly or indirectly by the consumer in the form of retail sales taxes, excise taxes, tariffs, value-added taxes (VAT), or income taxes where all savings are tax-deductible. of 7.5 percent.

- The proposed rate is based on flawed calculations that do not reflect the tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. defined in the underlying proposal.

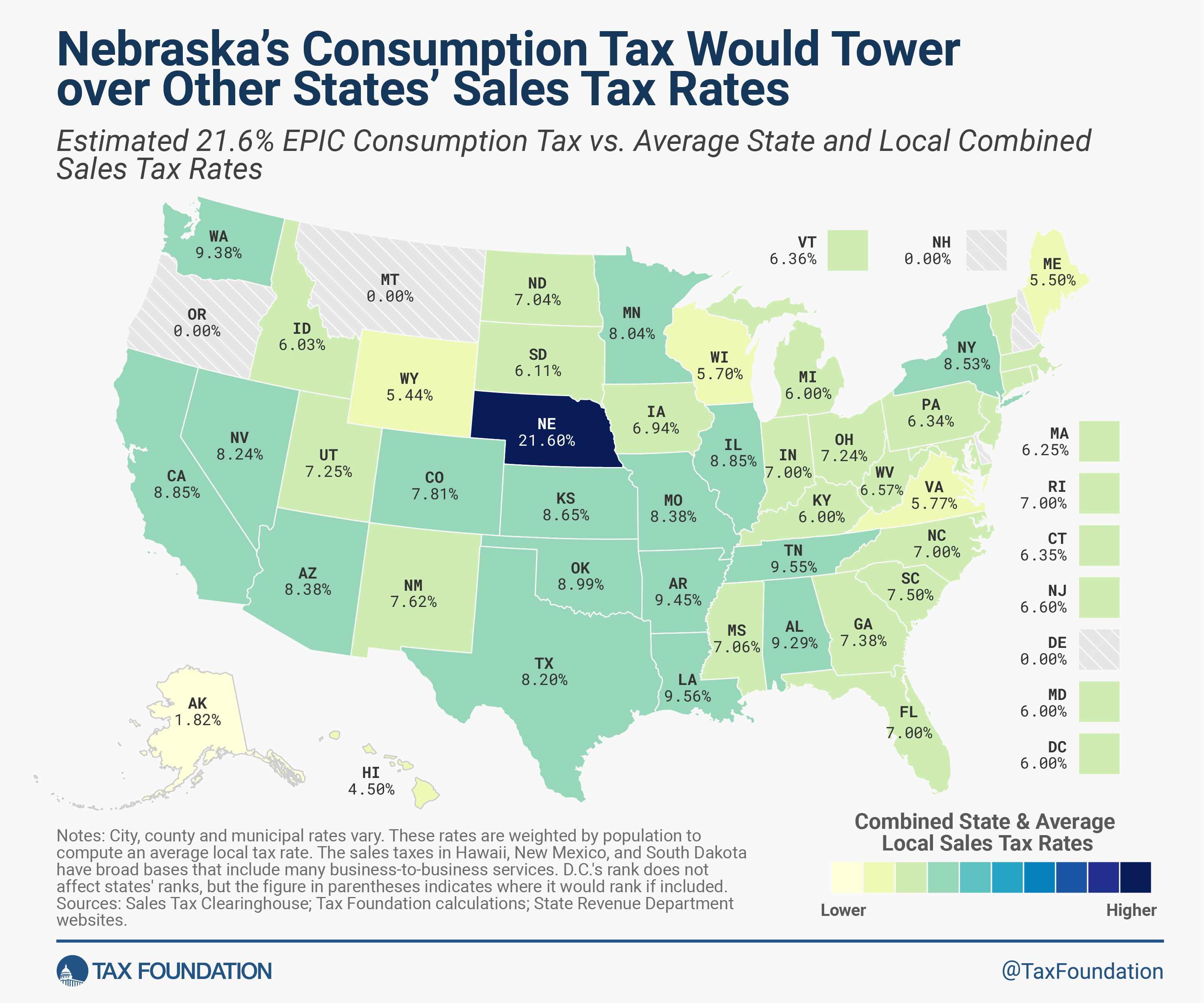

- TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. Foundation calculations suggest that the EPIC plan would require a statewide consumption tax rate of 21.6 percent or more.

- The EPIC Option does not prevent local governments from enacting consumption taxes, meaning the total rate could be much higher than advertised.

- EPIC would likely result in substantial cross-border shopping, allowing Nebraskans close to a border with a lower sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. state to avail themselves of the lower rates while leaving taxpayers in the interior of the state to bear the brunt of the newly established consumption tax.

- The anticipated economic benefits of the proposed tax overhaul are unlikely to materialize under such a high consumption tax rate.

- Policymakers seeking to constrain property taxes have better-targeted ways to achieve these aims.

Introduction

No state has ever abolished the property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services. , which is far and away the primary source of local government revenue in every state, but an ambitious Nebraska proposal would make the Cornhusker State the first to do so—and that’s just scratching the surface. The EPIC Option, which stands for Eliminate Property, Income (and Inheritance), and Corporate Taxes,[1] would do what it says on the label, repealing the majority of Nebraska’s taxes and replacing them with a broad-based consumption tax at an enticingly low rate of 7.5 percent. Unfortunately, there’s a problem with the ingredients list. Whereas proponents tout a study they commissioned identifying a 7.23 percent revenue-neutral consumption tax rate,[2] and the formal proposal is for a 7.5 percent rate,[3] a Tax Foundation analysis finds that the rate would need to be at least 21.6 percent to offset the foregone revenue. Concentrating state and local tax revenues in one exceedingly high-rate tax, moreover, would have deleterious economic effects. Rather than facilitating economic growth, this incredibly anomalous tax would undercut the state’s competitiveness.

Soaring property tax burdens are a genuine concern, and it is appropriate for policymakers to seek solutions. Advocates of the EPIC Option are correct, moreover, that consumption taxes are more conducive to growth than income taxes, introducing fewer economic distortions and creating a more favorable environment for investment and job creation. However, it is possible to have too much of a good thing, especially if the resulting system is so radically different than those of other states as to create uncompetitive arbitrage opportunities. And if income, property, inheritance, and the existing state and local sales taxes were all replaced by a consumption tax at the implausibly low 7.5 percent rate specified in the EPIC legislation, the result would be an unprecedented fiscal crisis, with Nebraska state and local governments losing roughly two-thirds of their existing revenues.

Background

Tax competition is real, and in recent years, Nebraska has made a concerted effort to enact pro-growth, competitive, tax reforms. Lawmakers continued this work in 2023 by accelerating previously enacted cuts to the individual and corporate tax rates. Enacted in May 2023, Legislative Bill 754 will phase down the state’s top marginal individual and corporate tax rates to 3.99 percent by 2027, with initial reductions of both top marginal rates to 5.84 percent in 2024, reaching the target three years earlier than initially projected.[4]

The same law also replaces Nebraska’s graduated-rate corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. into a single rate in 2025. Similarly, the state’s four marginal individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. rates will be consolidated into three beginning in 2026. With these reforms, the state’s competitiveness should grow. Each of these changes helps bring Nebraska in line with rate reductions and other reforms adopted in competitor states.

Addressing property taxes, however, has proven difficult, even though it is very much a priority for state lawmakers, who have devoted significant time and state resources to the task. Nebraska homeowners, like their peers across the country, have experienced a dramatic rise in assessed values in recent years, with the prospect of significantly increased tax burdens if millages (rates) are not reduced commensurately.

Property tax collections should not keep pace with soaring property values because the cost and value of government services are not dependent on those values. While inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. has increased the cost of government, there is no reason why a community where property values have increased by, say, 40 percent should have to remit 40 percent more in property taxes from that same set of properties. Residents are not receiving 40 percent more or better government for their money.

State lawmakers have sought to stem the rise in property taxes by creating, and expanding, a refundable income tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. to defray the cost of school district and community college real property taxes, and by restricting rate increases for school district property taxes. For homeowners, both measures are welcome, but they come with limitations that still leave many crying out for relief. Restricting an increase in rates is of limited utility when assessed values are rising fast enough to yield substantial property tax increases under unchanged rates. And while refundable income tax credits do reduce the overall bite of property taxes, they do not constrain it at its source, leaving localities and school districts free to increase property tax bills, confident in the knowledge that the state—using other revenue sources—will defray some of those costs. The result is not true tax relief, and even if they will receive an offset from the state, property owners still see that property tax bill and find it justifiably upsetting.

In this context, it is unsurprising that a proposal to solve the problem in the most straightforward way—by doing away with the property tax—has substantial appeal. But things that seem too good to be true often are. Proponents see their plan as “EPIC.” But the world of workable tax policy is rarely so swashbuckling. The EPIC Option is exciting, but its promise withers under further analysis.

An Introduction to EPIC

As noted, the EPIC initiative aims to eliminate almost all categories of taxation, including tax expenditures (e.g., deductions, credits, and exemptions—some of them tax preferences, but others forming structurally important parts of the tax code), and implement a consumption tax as the state’s primary revenue source, along with the maintenance of currently existing excise taxes. The consumption tax would be imposed on a relatively broad base, but one that nowhere near approaches all final consumption, with significant carveouts for groceries, insurance, most health and education spending, and more. Estimates commissioned by proponents suggest—implausibly—that a consumption tax rate of 7.23 percent in 2026 and 6.52 percent in 2030 could ensure sufficient revenue, though the plan calls for a rate of 7.5 percent.[5] The EPIC-commissioned economic analysis also observes that a lower rate could prevail if the grocery exemption were removed.[6]

The EPIC Option has been advanced both as legislation and, now, as a potential 2024 ballot measure. The ballot initiative would amend the state constitution to restrict Nebraska state and local governments to raising revenue from “retail consumption taxes and excise taxes,” eliminating property taxes, income taxes, sales taxes (other than the replacement consumption tax), and inheritance taxes. The constitutional amendment would also exempt groceries from taxation. It would then be up to the Unicameral to implement the new consumption tax legislation, though the vehicle for such action is Legislative Bill 79 of 2024, which follows in the footsteps of a prior legislative effort in 2021, LB 133.

The EPIC legislation specifically exempts several categories of purchases from the consumption tax, but these purchases may still be subject to other state taxes not specifically repealed. For example, insurance premiums and gasoline are not included in the consumption tax base but are still subject to state excise taxes. Despite the principle that the consumption tax would not apply to anything separately subject to an excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. , gaming—which is subject to a separate tax—is included in the consumption tax base.[7] While the sale of an existing structure is exempt, the services of the agent(s) for the buyer and seller may be subject to tax, and new construction would be taxed as well. Groceries consumed off premises are exempt, but prepared foods and foods consumed on premises are not. Curiously, government consumption and government-paid wages are subject to tax, which is unconstitutional as pertains to federal government employees and circular for state and local employees, with no net revenue generated by government paying itself.

Table 1. EPIC Tax Base Composition

| Included in the EPIC Consumption Tax Base | Excluded from the EPIC Consumption Tax Base |

|---|---|

| Purchases of new goods (e.g., new home, new car) | Purchases of used goods (e.g., previously owned cars and homes) |

| Professional services (e.g., legal, accounting, financial, gaming/gambling services, real estate services) | Purchases used in a trade or business (e.g., farm and ranch equipment, copy machines) |

| Prepared food and food for consumption on premises | Groceries for consumption off premises |

| Previously excluded items converted to personal use | Business-to-business transactions |

| Items purchased out-of-state (untaxed at origin) and brought into Nebraska for personal use | Any good or service subject to an existing excise tax (e.g., fuel, insurance premiums) |

| Out-of-pocket medical and dental bills | Insurance and insurance-covered health services |

| Government wages | Intangible property (e.g., copyrights, trademarks, patents) |

| Remodeling of or adding onto an existing property | Land and used structures |

| Rental of tangible property | Property or services used for educational purposes |

Commendably, the legislation exempts all intermediate transactions, avoiding what is known as tax pyramidingTax pyramiding occurs when the same final good or service is taxed multiple times along the production process. This yields vastly different effective tax rates depending on the length of the supply chain and disproportionately harms low-margin firms. Gross receipts taxes are a prime example of tax pyramiding in action. , where a final product has tax embedded in it multiple times, imposed at different points of the production process.[8] However, these business inputs currently comprise an estimated 44 percent of Nebraska’s sales tax base,[9] which is unusually high. Moving away from this uncompetitive system is highly desirable, and a growing number of states are working to reduce their taxation of these transactions. But the exclusion leaves a significant hole in the existing sales tax base, meaning that the newly taxed areas of personal consumption have to cover a substantial loss against the existing base before they can even begin to offset revenues from income, property, or inheritance taxes.

Moreover, EPIC has the potential to further distort Nebraska’s economy. As sales of newly constructed homes are subject to the consumption tax, EPIC could disincentivize home building. By way of example, a newly constructed home valued at $250,000 would cost a homebuyer $304,000 after tax under our calculations of a revenue-neutral rate. The additional cost imposed on the homebuyer, without an associated increase in the value of the home, may cause homebuyers to opt for existing construction, discouraging people from living in the homes they desire and making it dramatically more expensive to build new housing.

The analytical foundations underpinning EPIC are unsound. Below, we will analyze the assumptions used to justify the EPIC Option and demonstrate that the rate and base upon which EPIC relies will need to be dramatically increased and expanded for EPIC to achieve its goals of eliminating almost all other categories of taxation in Nebraska.

Corrected Calculations Yield a 21.6 Percent Consumption Tax Rate

Proponents tout a study asserting that Nebraska’s existing state income tax, state sales tax, local property tax, and local inheritance taxAn inheritance tax is levied upon the value of inherited assets received by a beneficiary after a decedent’s death. Not to be confused with estate taxes, which are paid by the decedent’s estate based on the size of the total estate before assets are distributed, inheritance taxes are paid by the recipient or heir based on the value of the bequest received. could all be replaced by a broad-based consumption tax at a rate of 7.23 percent.[10] This is not plausible, nor is the 7.5 percent rate reflected in LB 79. A Tax Foundation analysis estimates that the revenue replacement rate for a broad-based consumption tax consistent with the EPIC plan’s language would be 21.6 percent or more.

How could EPIC’s proponents come up with such an artificially low replacement tax rate? The answer appears to be a combination of errors and implausible assumptions.

Both the Tax Foundation and the study commissioned by EPIC’s supporters rely substantially on a dataset produced by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) detailing state-level personal consumption expenditures (PCE).[11] This dataset includes, among other things, both actual rental costs and what are known as implicit rents.

Economically speaking, both a homeowner and an apartment renter are “consuming” housing, even though the homeowner, rather than paying rent, is either making mortgage payments or—having paid off the home—not conducting any financial transactions. The BEA recognizes and puts a price tag on the homeowner’s consumption of housing. This makes sense in economic terms (absent home ownership, they would have to pay for housing some other way, and with home ownership, they’ve given up capital that could otherwise be put to other uses) but is not very useful for an analysis of a consumption tax, since clearly homeowners are not going to be taxed on the implicit rental costs of the home they own. Nor, we assume, would renters pay the tax.[12] These consumption costs need to be subtracted before using the dataset.

The EPIC-commissioned study acknowledges this and purports to do so. The figure used for personal consumption, however, is consistent with the headline PCE amount (adjusted to 2026) without any subtractions, including for actual or implicit rent. That’s the first problem, and it is a significant one.

Furthermore, the study does not seem to make any other adjustments from the PCE topline amount other than accounting for a grocery exclusion and an exemption for education services,[13] even when clearly warranted, or even provided for by the underlying proposal. For instance, the language of the EPIC proposal only taxes the share of health-care services procured through private out-of-pocket payment (e.g., not through insurance or under Medicare or Medicaid),[14] but the EPIC study appears to anticipate the taxation of all health expenditures in PCE—overstating the amount by 800 percent. Additionally, the EPIC legislation exempts any good or service otherwise taxed under an existing excise tax, but there is no indication that these consumption categories were excluded in their calculations.

Even if the goal was to tax health-care services broadly, an adjustment would have to be made for Medicare- and Medicaid-funded care, which is not legally taxable. Federal law also prohibits taxing internet access or federal government activities, including the USPS. Interstate travel costs, including airfare, are also largely out of reach. Consumption by nonprofits, and Nebraskans’ consumption while traveling, both of which are part of PCE, also need to be excluded. There is no indication, however, that the economic analysis incorporated any of these adjustments, and indeed their figures are inconsistent with any such adjustment.

The study also assumes that the state will be able to collect tax on 100 percent of the share of PCE it chooses to tax. The BEA’s datasets are the best available data for these estimates, which is why they are used by both the Tax Foundation in this analysis and EPIC proponents in their projections, but they are not perfect, and more importantly, no tax ever achieves full compliance. When using PCE to estimate sales tax revenue, it has become customary to assume 85 to 90 percent compliance, a rough rule of thumb designed to account for cross-border sales, casual sales, data limitations, and, of course, some level of error and tax fraud. We chose, optimistically, to use 90 percent, though a case can be made that this assumption is too generous, even before taking into account the effects of such a high rate on tax avoidance and evasion. EPIC proponents’ assumption that 100 percent of Nebraska taxable consumption will be taxed by the state is wildly unrealistic, even if one only considers cross-border transactions, like an Omaha resident making a purchase across the border in Iowa and paying Iowa sales tax instead.

On the flip side, the study does not seem to make a positive revenue adjustment for nonresident spending in Nebraska. In other words, it wrongly includes amounts that Nebraskans spend out-of-state, either due to cross-border shopping (e.g., buying something in Iowa) or travel (e.g., vacation spending in Hawaii), while also failing to account for the Nebraska-taxable spending of nonresidents when they visit Nebraska. We attempt to account for both, though this is likely generous, as nonresidents’ willingness to put up with a 21.6 percent rate may be limited.

Meanwhile, the commissioned study anticipates generating substantial revenue from taxing state and local government purchases as well as—most astonishingly—state and local government compensation. Here, another error slips in. About $1.7 billion in additional revenue is supposedly generated by taxing government consumption, salaries, and wages, but no adjustment is made to the amount of revenue the new tax needs to replace. Of course, no revenue is truly generated by the government taxing itself: the money goes out one door and in another. But by counting $1.7 billion in additional revenue on one side of the ledger but not recognizing it as having any effect on government balance sheets, proponents further contribute to the artificially low advertised consumption tax rate.

Less significantly, the Tax Foundation was unable to reproduce EPIC proponents’ estimates of the cost of new residential construction. Both the EPIC-commissioned study and the Tax Foundation use BEA national accounts data adjusted to yield a rough estimate of a Nebraska share. Reasonable differences can emerge in calculating a state-specific share of these national data (we opted to scale based on Nebraska’s share of national housing values), but our estimate of $3.9 billion in residential new construction and improvements is sharply divergent from EPIC’s $6.5 billion estimate.

Rate projections are based on revenue replacement. The EPIC-commissioned study, published in February 2023, had to rely on grossing up older data, while the Tax Foundation was able to employ the most recent revenue forecasts,[15] but fortuitously, these figures closely agree, with the EPIC study assuming that $11.67 billion in revenue would need to be replaced by calendar year 2026 while the Tax Foundation analysis assumes $11.81 billion. The EPIC study appears, however, to allow a nominal (non-inflation adjusted) growth rate of just under 2.4 percent per year, which is also unusually low, making its figures for 2030 less plausible. At the state level, growth has been about 3 percent in recent years, and about double that at the local level.

These errors and questionable assumptions add up. We find that the consumption tax base specified by the EPIC plan is only 45 percent as large as proponents anticipated.[16] Using the broad consumption tax base outlined in the EPIC amendment, the revenue replacement rate would have to be 2.5 times what proponents anticipated on a static basis, and, if this much higher tax wipes out the projected dynamic growth, almost 3 times the advertised rate for 2026: 21.6 percent rather than 7.23 percent.

Table 2. Nebraska’s Consumption Tax Rate Would Be over 21 Percent, Not 7.23 Percent

EPIC-Commissioned Study Compared to Tax Foundation Analysis

| Tax Base (Millions) | EPIC Study | Tax Foundation |

|---|---|---|

| Nebraskans’ Personal Consumption | $108,492 | $46,551 |

| Nonresident Personal Consumption | $0 | $1,868 |

| Government Consumption | $10,637 | $0 |

| Government Salaries & Wages | $9,342 | $0 |

| New Home Sales | $6,479 | $3,867 |

| Administrative Fee (0.25%) | -$337 | -$158 |

| Total Tax Base | $134,612 | $67,805 |

| Static Revenue Replacement Rate (2026) | 8.67% | 21.60% |

| Dynamic Revenue Replacement Rate (2026) | 7.23% | n.a. |

Source: David G. Tuerck, “The Fiscal & Economic Effects of the Proposed EPIC Consumption Tax in Nebraska,” The Beacon Hill Institute for Public Policy Research, February 2023 (EPIC-commissioned study); U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis; Tax Foundation calculations.

The crux of the deal the EPIC Option offers Nebraskans is to accept a broad-based consumption tax in lieu of most existing taxes. This means taxing new construction, out-of-pocket health-care expenses, financial services, professional services like legal and accounting services (when purchased by consumers), gaming, and the like. Good arguments can be advanced for taxing some or all of these categories of consumption, particularly if it results in the elimination of other taxes. If a 7.5 percent rate on this tax base, as included in the legislation, could really replace all these other taxes, it would be a remarkably good deal that Nebraskans would be well-advised to adopt.

But the reality is that the breadth of the proposed EPIC consumption tax is not much broader than that of the current sales tax. It is better designed, as it avoids the taxation of business inputs (much of which is ultimately passed on to consumers) and instead captures a broader base of personal consumption, but it is still less than 25 percent broader than the current sales tax base. In this context, the problem is obvious: clearly Nebraska cannot fund the elimination of the state income tax, local sales taxes, local property taxes, and the inheritance tax all by increasing state sales tax revenue by less than 25 percent.

The Problem of Cross-Border Shopping

Even a 7.5 percent consumption tax rate would be the highest statewide levy on similar purchases in the country, and above average even when taking into account other states’ local sales taxes. But at 21.6 percent, Nebraska’s consumption tax rate would tower over any other state’s sales tax rate. Nebraska’s neighbors have combined sales tax rates ranging from 5.44 percent in Wyoming to 8.65 percent in Kansas, and many Nebraskans live near a state border. This creates a substantial incentive for cross-border shopping to avoid the burden of the proposed consumption tax. Nearly 30 percent of the state’s population is in Douglas County (where Omaha is located), situated along the Iowa border. Another 16.5 percent of the state’s population is in Lancaster County (Lincoln), considerably further from a state boundary, but still not so far as to make cross-border shopping impractical for high-cost items.

Moreover, the EPIC plan allows local jurisdictions to impose their own consumption taxes, which could increase the combined tax rate above and beyond the 21.6 percent we estimate. The uniquely high rate of the statewide consumption tax, combined with the local option tax, could result in greater rates of cross-border shopping for those Nebraskans close enough to lower tax jurisdictions, eroding the revenue the state is counting on from the tax and leaving those in the interior of the state to bear the brunt of the newly increased tax.

Researchers have investigated the incidence of cross-border shopping resulting from changes in sales tax rates. One such study focused on Nebraska and found that a one percent increase in the local sales tax rate would result in a 3.94 percent increase in cross-border shopping in a city with an adjacent lower-tax jurisdiction and by 2.53 percent in a jurisdiction that is a 20-minute drive from its closest neighbor.[17] The study also shows that these incentives are greatly reduced in a locality that is a 50-mile drive to its closest neighbor, demonstrating that proximity to lower sales tax rates corresponds with greater cross-border shopping.[18] The current state-level sales tax in Nebraska is 5.5 percent, with the average local option sales tax raising the total burden to 6.96 percent. This combined rate is in line with regional competitors. But if the new rate were 21.6 percent or more, an Omaha resident would have a strong incentive to shop in neighboring Iowa (6.94 percent combined average rate).

The EPIC legislation attempts to disincentivize out-of-state cross-border shopping by requiring individuals to remit the consumption tax on products brought into the state for personal use. However, although the legislation is unclear on this point, use taxes—which are part of all states’ sales tax codes—do not apply where sales tax has already been charged.

If, for instance, a Nebraska resident orders a product from Iowa and it is shipped to her, Nebraska sales tax will be charged, since sales taxes are typically destination-sourced. If they purchase the product elsewhere and, because the item is destined for Nebraska, no sales tax is charged, they would be responsible for remitting use tax (either under the current system or under the proposed EPIC tax) to Nebraska. But if they shopped in Iowa and paid Iowa sales tax, then Nebraska use tax would not ordinarily apply.

If the EPIC Option contemplates imposing another layer of Nebraska tax on a good already taxed in another state, this raises constitutional questions by imposing unique burdens on interstate commerce, as out-of-state purchases would be subject to two taxes. And if that is not the intent, and EPIC would enact a typical compensating use tax (for which consumer compliance has always been quite low[19]), then nothing would prevent residents from saving substantially by purchasing goods across state borders.

Dynamic ScoringDynamic scoring estimates the effect of tax changes on key economic factors, such as jobs, wages, investment, federal revenue, and GDP. It is a tool policymakers can use to differentiate between tax changes that look similar using conventional scoring but have vastly different effects on economic growth.

In recent years, it has become more common to score tax and spending proposals dynamically (i.e., taking their economic impacts into account). If, for instance, an income tax rate reduction yields higher rates of investment and thus generates additional state income, then the lower rate will apply to a broader base of taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. Taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. , partially defraying the government cost of the tax reduction. Tax cuts almost never “pay for themselves,” but responsible tax reductions do enable economic growth that reduces their cost. The Tax Foundation applies dynamic scoring to federal tax proposals, as does the U.S. Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT). The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center’s tax model and the Penn Wharton Budget Model also incorporate dynamic scoring, and appropriately so.

It is not unreasonable, therefore, that the EPIC-commissioned study would attempt to score these broader economic impacts. But it must be remembered that they scored a massively lower rate. On a static basis, the study assumed that it would take an 8.67 percent rate to achieve revenue neutrality, but taking economic growth into account, they landed on 7.23 percent as the break-even point. If, of course, the static rate is actually 21.6 percent, the economic incentives look radically different, and behavioral responses to the tax will likely erode revenues still further. Perhaps some people would be favorably motivated by such a tax structure; imagine, for instance, a wealthy individual who relied heavily on out-of-state consumption but took advantage of the lack of income or property taxes. Such individuals, of course, would not contribute much to the state’s coffers even if they were attracted to the state because the EPIC Option was in place.

On the other hand, many existing residents would find the cost of in-state purchases exorbitant and would look for legal (cross-border shopping) and illegal (black and gray markets) ways to avoid the consumption tax. Proponents’ assumption that the plan would grow the taxable base is doubtful at best. Rather than a positive dynamic feedback effect, it is easy to imagine a negative one, where the taxable base shrinks in response to the law.

Property Taxes and Sound Relief Alternatives to EPIC

When structured correctly, the property tax is relatively efficient. Few taxes are more transparent as the tax is levied against owners based on a property’s assessed value, which is often shared directly with the taxpayer. Payment, too, in many instances is made directly to the government by the taxpayer, unless held in escrow by a mortgage company.

A well-designed property tax is more neutral than most other taxes. It corresponds, albeit imperfectly, with the value of the overall benefits received by the property owner (e.g., police and fire protection, roads, and schools). Consequently, many potential replacements for property tax revenue do more economic harm than the tax they replace, as would be the case with EPIC. Moreover, the property tax is often one of the few revenue generators available to local governments, making its reform contentious even when justified.

When property tax valuations rise sharply, as has happened in recent years, taxpayers are left asking why the same property should now come with dramatically higher property taxes. Even if all properties in a jurisdiction see a dramatic increase in market value, this does not automatically make it more costly to provide government services to those properties. Homeowners might reasonably expect to pay lower rates when values rise, since the tax’s base is now broader. That has not always happened, and is the source of considerable frustration.

There are three primary ways that governments can limit the growth of property taxes: assessment limits, rate limits, and levy (collections) limits. Assessment limits create significant market distortions and other inequities. Rate limits do nothing to prevent tax bills from soaring when assessed values rise and are the most easily undermined by local government. Levy limits restrict revenue collections in the most neutral manner, reducing overall property tax millages to offset jurisdiction-wide increases in assessed values.[20]

Rate limits are implemented to restrain local officials from increasing the property tax burden through legislative increases in the tax rate. Assessment limits prevent a property owner from losing their home when there is a sharp rise in property valuations. There is a certain logic to this. While wealth and income are both measures of financial security, one does not necessarily track the other. A taxpayer’s net assets may give the impression of wealth, but income liquidity defines immediate purchasing power. As property valuations rise, a taxpayer will appear wealthier, but without a commensurate increase in real income, the taxpayer may not be able to afford the rise in property taxes. Assessment limits recognize this discrepancy and seek to prevent the disparity between wealth and income from causing one to be priced out of their home.

As noted, rate limits do little to protect from surging valuations as the same tax rate applied to a dramatically increased property value will result in more taxes owed. Assessment limits, for their part, create troubling market distortions that more than offset their policy benefits. For example, assessment limits require that a greater share of property tax revenue be collected from newer or improved homes, with burdens shifted to these properties since existing unsold properties are held in check. This creates a lock-in effect where existing homeowners are discouraged from selling (whether to upgrade or downsize).

Similarly, assessment limits can mute the desire to undertake major home renovation projects because such projects might also trigger a new tax assessment. They also discourage new construction because these buildings will likely be assessed at a higher value than a substantially similar property built a few years earlier. In fact, it is entirely possible for two nearly identical properties in the same neighborhood to pay drastically different property taxes based only on purchase date. The sum of these market distortions hurts not only home builders and home sellers, but also a community’s younger population and lower-income families that will find it harder to secure a starter home, and in turn, build wealth. Over time, assessment limits reduce housing availability and drive up the cost of living.

Conversely, levy limits constrain revenue growth. This prevents local governments from reaping a windfall when property valuations rise dramatically. While individual tax liability could increase or decrease due to assessed values and rate changes, revenue collection in the aggregate is constrained. Property tax liability is still associated with market value, such that some homeowners are not favored over others, but everyone sees their millages rolled back when assessed values soar. Consequently, levy limits do not create the same inequities that result from assessment limits, and by limiting collections, they help avoid out-of-control tax increases that can occur with only a rate limit.

Beyond restrictions on local government tax increases, states can also defray property tax burdens through transfers or offsets, like Nebraska already does with the Nebraska Property Tax Incentive Act. Such approaches are more practical than the EPIC Option, but still involve tradeoffs and require careful design to ensure that they do not facilitate an increase in overall levels of taxation, which can happen if future local property tax increases are not constrained, and localities conclude that they have more fiscal space in which to operate due to offsetting state relief.

The most effective property tax relief programs pair collections limitations with spending restraint. Nebraska could reform and tighten its existing rate and levy limits to protect homeowners from unnecessary property tax increases without doing anything as drastic as eliminating the tax outright.

Conclusion

The EPIC proposal is built on a faulty foundation that could negatively impact Nebraskans and the state’s economy. If the EPIC Option were implemented, the progress legislators have made to date on tax competitiveness would be eroded and replaced with an uncompetitive tax code, both regionally and nationally. The proposal’s contemplated consumption tax rate of 7.5 percent dramatically underfunds state coffers, requiring a rate of over 21 percent to fund the government at its current levels. That means the legislature will almost immediately be called upon to increase the statewide consumption tax rate, as allowed by the statute.

Of course, not all that EPIC proposes is bad policy. The state should consider repealing the inheritance tax, as EPIC does. The state should also consider adopting a competitive tangible personal property de minimis exemption, which would help remove a significant number of small businesses from the rolls of this inefficient property tax. The state could also decouple from the federal tax code for purposes of permanent full expensingFull expensing allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of certain investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings. It alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. , making qualifying capital expenses in the state profitable from year one.[21]

For real property owners, Nebraska currently employs both rate and levy limitations to limit property tax liability. Rate limits, however, do nothing to prevent increased tax liability resulting from sudden valuation surges, as have been seen throughout the country. For its part, the current levy limit dates to 1998 when it imposed a cap of $2.19 per $100 of property value. However, the limit does not apply to bond issues, meaning taxpayers can pay more than the $2.19 cap. Therefore, the statewide limitation is neither effective nor transparent as it can be increased at the local level.[22] Policymakers would do well to reform the levy limit to ensure that property taxes are not increasing without justification. There are plenty of reforms for lawmakers to consider. From these reforms, EPIC is a major, unworkable distraction.

EPIC dramatically overpromises, underfunds the government, and could place Nebraskans in a precarious economic position. Proponents seek to do at the ballot what was unachievable in the legislature. Fortunately, the state has better options and should consider moving forward with them rather than adopting an unproven and unsound plan.

After all, something can be epic—but it can also be an epic, in the sense of some sweeping, consequential story. Unfortunately, many of the great epic tales are tragedies, or at least involve them. The art of doing policy is that of navigating between Charybdis and Scylla, but the EPIC Option runs headlong into crisis. Either Nebraskans would face the Scyllan rock of an impossibly high 21.6 percent consumption tax or the Charybdian whirlpool of depriving the government of two-thirds of its revenue and seeing what happens. If neither option is enticing, then Nebraskans should focus their efforts on other, more responsible methods of keeping property taxes in check, methods that provide both tax competitiveness and revenue stability.

Methodology

Methodological Notes

In calculating a revenue-neutral tax rate of 21.6 percent, the Tax Foundation began with the following inputs:

- Nebraska personal consumption expenditures (PCE) for 2022, grossed up according to current forecasts of PCE growth to yield a 2026 figure[23]

- Nebraska new construction costs, derived from national-level NIPA data on new structures, allocated to Nebraska according to Nebraska’s Census-calculated share of national residential property value and grossed up consistent with PCE[24]

- Nonresident expenditures in Nebraska, based on Nebraska Tourism Commission-funded estimates of taxable categories of in-state nonresident spending, and grossed up to 2026 levels[25]

We then subtracted the following categories of PCE as either expressly exempt under the EPIC proposal or untaxable due to the lack of consideration (no exchange taking place) or a federal prohibition, with adjustments to 2026 levels:

- Groceries, by excluding the share of food for home consumption constituting groceries, based on the Consumer Expenditure Survey[26]

- Imputed rents from home ownership and rental costs of residential leases, as broken out in the PCE dataset

- Insurance, as broken out in the PCE dataset

- Private education costs, as broken out in the PCE dataset

- Used vehicle purchases, as broken out in the PCE dataset

- Internet service, USPS services, international expenditures, and consumption financed by nonprofits, as broken out in the PCE dataset

- Goods subject to existing excise taxes, like gasoline, tobacco, and alcohol, as broken out in the PCE dataset and using U.S. Energy Information Administration data to back out the appropriate share of the broader category of motor fuels and fluids associated with gasoline[27]

- Health-care costs borne by Medicare, Medicaid, or private insurer payments, using a national ratio provided by the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services[28]

- Existing sales tax embedded within PCE, prorated according to the Council on State Taxation’s analysis of the share of Nebraska’s current sales tax imposed on personal consumption[29]

- Rates of tax avoidance due to cross-border shopping, travel, and noncompliance, assumed at 10 percent of PCE

- The administrative fee, at 0.25 percent of collections

[1] EPIC Option, https://epicoption.org/.

[2] David G. Tuerck, “The Fiscal & Economic Effects of the Proposed EPIC Consumption Tax in Nebraska,” The Beacon Hill Institute for Public Policy Research, February 2023, https://epicconsumptiontax.org/bhi-study.

[3] Nebraska Legislative Bill 79 (2024), https://nebraskalegislature.gov/bills/view_bill.php?DocumentID=50183.

[4] Nebraska Legislative Bill 754 (2024), https://nebraskalegislature.gov/bills/view_bill.php?DocumentID=50792. For Tax Foundation legislative testimony on LB 754, see Katherine Loughead, “Testimony: Considerations for Additional Income Tax Reform and Relief in Nebraska,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 3, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/state/nebraska-income-tax-reform-relief/.

[5] David G. Tuerck, “The Fiscal & Economic Effects of the Proposed EPIC Consumption Tax in Nebraska.”

[6] Id. See also Nebraska LB 79, Amendment 314 (proposing a consumption tax rate of 7.5 percent).

[7] One could plausibly argue that the tax on gross gaming revenues, which is more of a gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total of all income received from any source before taxes or deductions. It includes wages, salaries, tips, interest, dividends, capital gains, rental income, alimony, pensions, and other forms of income. For businesses, gross income (or gross profit) is the sum of total receipts or sales minus the cost of goods sold (COGS)—the direct costs of producing goods, including inventory and certain labor costs. tax (though not, evidently, deemed precluded by the limitations in the proposed constitutional amendment), is on a sufficiently distinct base as to not be another ad valorem tax on gaming, in addition to the new consumption tax.

[8] For a discussion of the sales tax treatment of business inputs, and how such taxation affects both consumers and investors, see Jared Walczak, Katherine Loughead, and Andrey Yushkov, “Kentucky Sales Tax Modernization: Keeping the Sales Tax on Sales, Not Production,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 24, 2024, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/state/kentucky-sales-tax-reform/, 3-15.

[9] Andrew Phillips and Muath Ibaid, “The Impact of Imposing Sales Taxes on Business Inputs,” State Tax Research Institute and the Council on State Taxation, May 2019, https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/en_us/news/2019/06/ey-the-impact-of-imposing-sales-taxes-on-business-inputs.pdf, 8.

[10] David G. Tuerck, “The Fiscal & Economic Effects of the Proposed EPIC Consumption Tax in Nebraska.”

[11] U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “SAPCE4 Personal consumption expenditures (PCE) by state by function” (Nebraska), https://www.bea.gov/itable/regional-gdp-and-personal-income.

[12] While the legislation taxes rent, there is an exclusion for the rental of used property. We infer that, since new construction is subject to tax, the rental of a dwelling on which tax has already been paid (or would have been paid had the tax been in effect when it was built) would fall under the exemption for used property and be exempt from tax. Were this not the case, there would be an enormous bias against renters and rental properties.

[13] Even here, it is not obvious that this has been done, but given that the study does not explicitly state what annual growth rate it assumed in projecting 2026 PCE, it is difficult to be certain. Nevertheless, total PCE in their 2019 base year (the Tax Foundation analysis uses 2022 figures grossed up according to recent PCE growth forecasts) was $79.9 billion, and the EPIC calculation includes $108.5 billion as a taxable share in 2026, which represents 35.8 percent nominal growth based on the total amount, or 79.8 percent growth if they had backed out housing, groceries, and education. This is before any dynamic adjustments based on presumed economic or population growth due to the implementation of the EPIC plan. Suffice it to say, personal consumption, which grew a cumulative 21.5 percent in nominal terms (not inflation-adjusted) in the prior seven years—in line with long-term trends—should not be expected to soar 79.8 percent in the subsequent seven.

[14] To be fair, the legislation only clearly excludes health care purchased through insurance, and it is not clear that government insurance programs are contemplated in this definition. However, federal law prohibits the taxation of Medicare and Medicaid expenditures, so these would not be taxed regardless of the intentions of EPIC’s supporters, and are excluded in our calculations.

[15] Nebraska Legislative Fiscal Office, “Tax Rate Review Committee Annual Report,” Nov. 20, 2023, https://nebraskalegislature.gov/pdf/reports/fiscal/taxratereview_annual_2023.pdf.

[16] These figures are based on the study’s own data sources, since the analysis relied on 2019 pre-pandemic consumption figures. Consumption soared during the pandemic, which arguably makes the pre-pandemic figures a better baseline, but we have taken the approach of using the most recent 2022 data with adjustments based on current PCE forecasts, which show a much lower rate of growth than the EPIC-commissioned analysis entailed.

[17] Iksoo Cho, “Local Sales Tax, Cross-Border Shopping, and Travel Cost,” Nebraska Department of Revenue, Mar. 29, 2016 (revised Nov. 24, 2017), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2756208.

[18] Id.

[19] Many states have even included space on state income tax returns to make reporting of use tax obligations easier. However, compliance rates have proved to be low as taxpayers rarely report and remit use taxes for out-of-state purchases. See James Alm and Mikhail I. Melnik, “Cross‐border shopping and state use tax liabilities: Evidence from eBay transactions,” Public Budgeting & Finance 32.1 (2012): 5-35.

[20] For a more comprehensive treatment of assessment, rate, and levy limits, see Jared Walczak, “Property Tax Limitation Regimes: A Primer,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 23, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/state/property-tax-limitation-regimes-primer/.

[21] For an overview of tax reform options for Nebraska, see Katherine Loughead, “Thirteen Priorities for Pro-Growth Tax Modernization in Nebraska,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 2, 2021, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/state/nebraska-tax-modernization/.

[22] Manish Bhatt, “Evaluating Nebraska Governor’s Plan for Property Tax Relief.”

[23] U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “SAPCE4 Personal consumption expenditures (PCE) by state by function” (Nebraska).

[24] Id., “Table 5.4.6U. Private Fixed Investment in Structures by Type, Chained dollars,” https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/?reqid=19&step=3&isuri=1&1921=underlying&1903=2031; U.S. Census Bureau, S2506 and 2507, https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST1Y2022.S2506 and https://data.census.gov/table/ACSST1Y2022.S2507.

Census Bureau, “New Residential Construction,” https://www.census.gov/construction/nrc/index.html.

[25] Dean Runyan Associates, “The Economic Impact of Travel,” Prepared for the Nebraska Tourism Commission, October 2022, https://visitnebraska.com/sites/default/files/2022-11/Nebraska_Final_2021p.pdf.

[26] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Expenditure Survey Table 1110 (2019), https://www.bls.gov/cex/tables/calendar-year/mean/cu-all-detail-2019.pdf.

[27] U.S. Energy Information Administration, “Motor gasoline consumption, price, and expenditure estimates, 2022,” https://www.eia.gov/state/seds/sep_fuel/html/fuel_mg.html.

[28] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, NHE Fact Sheet (2022), https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/national-health-expenditure-data/nhe-fact-sheet.

[29] Andrew Phillips and Muath Ibaid, “The Impact of Imposing Sales Tax on Business Inputs.”

Share this article