Introduction

In recent years, Iowa’s taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. code has undergone a transformation. Individual and corporate income taxes have been simplified, and rates have come down—dramatically. The inheritance taxAn inheritance tax is levied upon the value of inherited assets received by a beneficiary after a decedent’s death. Not to be confused with estate taxes, which are paid by the decedent’s estate based on the size of the total estate before assets are distributed, inheritance taxes are paid by the recipient or heir based on the value of the bequest received. is gone. So is the alternative minimum tax. Iowa is a more economically competitive, lower-tax state thanks to these reforms. But for many taxpayers, there’s at least one more item on the agenda: property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services. reform and relief. Lawmakers adopted reforms in 2023, but those efforts fall short of many taxpayers’ hopes, and their design will yield uneven relief.

The clamor for property tax relief is not unique to Iowa; it has emerged as a dominant theme in state tax policy across the country, and for good reason. With assessed values skyrocketing in recent years, many homeowners now pay dramatically more than they used to, and they’re left wondering why they should have to pay so much more for the same property, and for the same government services.

Reforming the property tax, however, is not easy. Some superficially appealing solutions are likely to backfire on homeowners in the long run, while meaningful reform and relief will involve revisiting a tangle of existing provisions that aren’t fully working as intended.

This publication considers the legitimate place of property taxes as a source of local revenue, surveys Iowa’s existing property tax system, puts Iowa tax burdens in a regional and national context, and compares and contrasts the leading approaches to providing property tax relief, culminating in recommendations for delivering effective, sustainable, and non-distortionary property tax relief. With a well-designed package of property tax reform, Iowa would round out its tax overhaul with a flourish—and give homeowners, farmers, and businesses a much-needed win.

Why Property Taxes?

Property taxes play a crucial role in funding local government in Iowa and across the country, generating revenue for schools and community colleges, local roads, local law enforcement, county hospitals, and other local government services.

Nevertheless, taxes are virtually no one’s idea of a popular tax—unless you manage to only survey economists. It’s worth asking why public finance experts appreciate the property tax when so many taxpayers viscerally dislike it, as it can help inform options for property tax relief. The basic case for property taxes rests on the following premises, which are well-supported by the economic literature:

- Property taxes do less economic harm than alternative ways to raise the same amount of revenue, making them more economically efficient than the alternatives. Basically, if you have to raise a given sum, property taxes are better for economic growth than are sales taxes or, especially, income taxes.

- Property taxes have less of an effect on decision-making—including location decisions—than most other taxes, making them less distortionary than the alternatives. Occasionally policymakers do want to influence behavior through taxation (this is a common justification for so-called “vice taxes”), but in most cases, there’s a broad consensus that it’s better to leave most individual and business decisions to the market and the private realm.

- Property taxes roughly align with the benefits that property owners receive from local services, making them more equitable than the alternatives.

- Property taxes are highly transparent and correlate strongly with services that enhance the value and utility of property, making them unusually sensitive to local preferences on the size and scope of government.

A wealth of studies demonstrate that property taxes are less harmful to economic growth than the major alternatives (income and sales taxes).[1] And there are good economic reasons why this is the case.

Real property taxes fall on land and improvements. Land itself is a fixed asset; the supply of land does not change with property taxes. An income tax, by reducing the returns to labor and investment, has a negative effect on labor force participation, productivity, and capital formation. A tax on land cannot, by contrast, decrease the amount of land.

At the margin, of course, property taxes can affect how much land can be used productively. Specifically, they may impact the capital invested in improving the land—improving or irrigating agricultural land to make it suitable for crops, say, or building a house or an apartment complex on it rather than leaving it vacant or putting it to some lesser use. But the part of the property tax that falls on the land itself creates extremely few distortions.

Even where the improvements are concerned, research suggests that property taxes do relatively little to distort economic decision-making, since (unlike income or sales taxes) the tax does not penalize productivity or consumption. Those taxes reduce incentives to work, invest, or consume. The property tax does none of those things, at least not to the same degree. Elasticities—the economic term for the responsiveness of quantities supplied or demanded to other factors, including tax costs— are lower and thus the imposition of property taxes leads to fewer deadweight losses, because property is not quickly or easily added or removed.

Property taxes also better align with benefits received than other broad-based taxes. Whereas federal and state taxes fund many programs that provide no direct benefit to those remitting the taxes (which is simply the reality, and not a judgment on the value of those expenditures), most local government expenditures—roads, schools, police, emergency services, parks, waste management, etc.—have a direct bearing on the quality of life of property owners, and often enhance the value of property.[2]

Businesses do not have children, but benefit from good schools, as do childless homeowners who not only enjoy the broad social benefits of a jurisdiction with a quality education system, but also see their home appreciate in value because it is in a good school district. The value of your home is a far better proxy for the benefits you receive from local government than your income or how much you consume.

Finally, the transparency of property taxes—most homeowners know their property tax bill quite well; does anyone know how much they pay in sales taxA sales tax is levied on retail sales of goods and services and, ideally, should apply to all final consumption with few exemptions. Many governments exempt goods like groceries; base broadening, such as including groceries, could keep rates lower. A sales tax should exempt business-to-business transactions which, when taxed, cause tax pyramiding. ?—contributes to the unpopularity of the tax, but is also a good argument in its favor. When property taxes are too high, opposition arises quickly and often gets results. That’s a feature, not a bug.[3]

Iowa’s Property Tax Burdens

With valuations rising considerably in recent years, many Iowans are understandably calling for significant relief. But whereas in many states property taxes have soared across the board, Iowa’s central challenge is a property tax limitation regime that does a decent job of keeping statewide property tax collections growth in check, but which allows significant regional variations, leading to eyewatering tax increases in some regions.

Property taxes comprise roughly a quarter of Iowa’s total tax burden. Between 2018 and 2024, taxable assessed values have grown from $160 billion to $202 billion,[4] an increase of nearly 27 percent over six years, or an average annual growth rate of approximately 4.44 percent. And the increase would have been much higher absent Iowa’s rollback system, which discounts the market value for tax purposes. Actual home prices in Iowa increased by 52 percent in nominal terms since 2018, while nationally, home prices soared by 69 percent.[5]

Over the same period, taxes levied on these properties increased from $4.91 billion to $5.99 billion (not including special districts and assessments), a growth of 21.97 percent, at an average of 3.66 percent. Notably, adjusting for inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. , this represents a decline in property tax collections: on an inflation-adjusted basis, Iowa would expect to have collected about $6.25 billion in 2024 to remain level with 2018. It did not. And if that were the end of the story, Iowans would have reason to cheer.

Of course, it isn’t.

Tax growth varied widely, from negative in a few counties to nearly doubling in others, indicating diverse local policies or economic conditions. The highest growth was in Guthrie County, which exhibited an increase of 94 percent between 2018 and 2024. On the other end of the spectrum, taxes in Palo Alto County actually shrank by 6.7 percent over the period. The unweighted average growth rate was 26 percent among the counties across these six years, with a median of 20 percent.

Here too, if increases simply reflected growing populations, there would be no need for concern. If Guthrie County had doubled in population or if all of its anomalous increase could be chalked up to some new development, the system would be running smoothly.

It isn’t.

Table 1. Counties with the Largest Tax Growth

| County | Increase |

|---|---|

| Guthrie | 94% |

| Lee | 77% |

| Ida | 67% |

| Benton | 57% |

| Carroll | 55% |

In practice, increases in tax collections appear to have little to do with new construction. Instead, they are a response to growing budgets and a statewide rollback system (about which, more later) which keeps statewide growth in check but permits large swings in individual counties.

On a per capita basis, county, city, and school district taxes increased from $1,558 in 2018 to $1,847 in 2024 in nominal terms, implying a growth of 18.5 percent (3.1 percent average). Similarly, per household property taxes increased 17.1 percent from $3,906 to $4,576 (average of 2.9 percent). The fastest growth was seen right after the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, when both per capita and household burdens grew by 5 percent between 2020 and 2022. This includes all property taxes—residential, commercial, industrial, agricultural, and state-assessed (utilities and railroads).[6]

From the outset, Iowa’s property taxes have been on the higher side. This is especially true of commercial property taxes, but it’s true—at least regionally, and certainly going by effective rates—for homeowners as well. For owner-occupied property, effective rates in Iowa are lower than in Nebraska, but higher than in other neighboring states, though actual property tax bills are not the national outliers that many might expect.

Using the latest available aggregate data from the US Census (2022) that includes special districts and bond repayments and extrapolating forward, all property taxes—commercial, industrial, and agricultural as well as residential—worked out to an estimated $5,623 per Iowa household in 2024. This is, of course, considerably more than the amount that homeowners themselves pay directly in taxes on their own residence, since it is an average of all classes of taxed property.[7]

In Nebraska, total property taxes (again, across all taxes, not just residential property) worked out to $6,278 per household in 2024. These figures are 12 percent higher than in Iowa, and Nebraska’s unusually high property taxes prompted the enactment of a reform package in 2024 special session. On the other hand, Indiana has a per household burden of $3,540. Household figures for Ohio ($4,620) and Missouri ($4,266) were also lower than those for Iowa ($5,623).[8]

But what about homeowners themselves? Drilling down to owner-occupied housing, the median homeowner in Iowa pays $2,825 on their home, which is actually slightly lower than the national average of $3,073, despite facing a much higher average effective rate (1.40 percent) than the national average (0.91 percent).[9]

At some level, it is reasonable and unsurprising that mill levies themselves would be higher in states with relatively lower home values. While the cost of providing a quality education, local roads, and local services is not as expensive in Iowa as it is in some parts of the country, per pupil expenditures don’t run half as much just because home prices are half that of another jurisdiction. In parts of the country with lower land values, mill levies tend to be higher to generate the necessary revenue to fund local government. A state or jurisdiction where the median home price is $250,000 is likely to require fewer tax dollars than a jurisdiction where the median price is $500,000, but not 50 percent less.

Like many other midwestern states, Iowa generates considerably less than the national average per $1,000 of market value (mill), raising an estimated $202 per mill compared to $338 nationally. Unsurprisingly, this forces Iowa’s rates higher. Still, Iowa stands out (after Nebraska) from its regional competitors, if not nationally, for its relatively high property taxes.

Table 2. Iowa’s Property Taxes Are High Regionally But Not Nationally

| State | Average Effective Rate | Median Tax Bill | Amount Per Mill |

|---|---|---|---|

| US Average | 0.91% | $3,073 | $338 |

| Iowa | 1.40% | $2,825 | $202 |

| Indiana | 0.71% | $1,640 | $231 |

| Missouri | 0.82% | $1,903 | $232 |

| Nebraska | 1.44% | $3,490 | $242 |

| Ohio | 1.30% | $2,748 | $211 |

Iowa’s Current Property Tax System

Tax-Setting Process

Iowa’s property tax system can be traced back to 1839, but it emerged in its contemporary form in 1971, with the passage of the School Finance Formula Act, which established foundational local school funding via a uniform mill levy of $20 in property taxes and established basic state aid equivalent to 70 percent of the state cost per pupil, a figure that was to increase incrementally to 80 percent.[10] It established a minimum of $200 per pupil of state spending and allowed districts to impose income tax surtaxes for education if approved at the ballot.

Incremental reforms throughout the 1970s and ’80s provided for equalization, measures to handle decreases in enrollment, adjusted mill rates to $5.40, and allowed students to enroll in any school district of their choice. A complete overhaul of the school funding formula was enacted in 1989, via the School and Area Education Agency Financing Act.[11]

Increasing costs and simultaneous increases in property taxes necessitated adjustments to state support to local districts, the temporary introduction of local option sales and use taxes, and measures to provide property tax relief, including the 2008 School Infrastructure Funding and Taxation bill, which created a special 1 percent state sales and use tax for school infrastructure.[12] The law required these funds to be deposited in the Secure an Advanced Vision for Education (SAVE) Fund and that those funds be distributed on a per pupil basis similar to the previous local option sales tax funds, effective July 1, 2009, with any excess going towards the Property Tax Equity and Relief (PTER) Fund, created to supplement property tax relief through the school aid formula.

Table 3. Beneficiaries of Iowa Property Tax Revenues

| Beneficiary | Property Tax Dollars | Percent of Total Property Tax Dollars | Percent Property Tax Change from Preceding Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| K-12 Schools | 2,927,288,000 | 39.96% | 5.25% |

| Counties | 1,604,880,000 | 21.91% | 7.61% |

| Cities | 2,205,136,000 | 30.1% | 8.54% |

| Community College | 231,702,000 | 3.16% | 7.49% |

| County Hospitals | 155,300,000 | 2.12% | 1.83% |

| Assessors | 75,037,000 | 1.02% | 7.7% |

| Townships | 46,891,000 | 0.64% | 4.25% |

| Ag Extension | 29,249,000 | 0.4% | 4.14% |

| Other | 49,417,000 | 0.68 | 11.7 |

Presently, the Iowa property tax primarily falls upon real property, including land, buildings, structures, and other improvements attached to or placed upon the land. The Iowa Department of Revenue (DOR) assesses various types of real property, which are classified into categories such as residential, agricultural, commercial, industrial, and utilities/railroad (state-assessed). The major recipients of property taxes levied in Iowa include K-12 schools, cities, counties, hospitals, community colleges, townships, and agricultural extension districts.

The property tax assessment process follows an 18-month cycle beginning on January 1 of the assessment year (the year prior to which the property taxes apply). The local designated assessor is responsible for determining the values and classification of individual parcels of property. These assessed values are then reported to the county auditor, who in turn reports them to the Iowa Department of Revenue for review. After this, the county auditor calculates the levy rates based on budget requirements provided by various local levying authorities. Once the levy rates are determined, the county auditor prepares the tax bills, which are then collected by the county treasurer.

Property taxes are paid in two installments: the first half is due in the fall of the following year, and the second half is due in the spring of the year after that. For instance, the assessment conducted on January 1, 2025, would apply to taxes due in the fall of 2026 and the spring of 2027 (fiscal year 2027).

Values for agricultural land is based on a five-year rolling average productivity formula that considers factors such as market values of crops, acreage under production, and the quantity harvested. The actual market value of the land is not part of the agricultural productivity formula.

The equalization process is a vital component of the property tax system in the state. Every odd-numbered year, the DOR reviews the aggregate assessed values submitted by local assessors for various property classifications, such as residential, commercial, and agricultural. If the department finds that the assessed values deviate more than 5 percent from the market value, it issues equalization orders to correct these discrepancies. These orders can result in either an increase or decrease in assessed values. Local assessors then implement these equalization orders, adjusting the assessed values of properties within their jurisdictions to align them with DOR directions.[13]

Property owners have the right to protest these adjustments if they believe the new assessments are unwarranted. Appeals are initially reviewed by the local board of review, and further by the Property Assessment Appeal Board and the district court. Once the equalization process is finalized, the adjusted values are used for calculating property taxes in the next assessment cycle.

Local governments, including counties, cities, and school districts, begin by preparing their budget proposals for the upcoming fiscal year, which runs from July 1 to the following June 30. These proposals are based on anticipated revenues and expenditures, and they must be submitted by April 30 before the upcoming fiscal year. Public hearings are held to allow citizens to voice their opinions and provide feedback on the proposed budgets. After considering public input, the local governing bodies—board of supervisors, city council, or school board—finalize and approve the budgets. Once the budgets are approved, they are certified by the county auditor and submitted to the Iowa Department of Management.

The department then certifies the taxes for the upcoming fiscal year. Taxing jurisdictions have specific levy limits, such as a general services levy limit of $3.50 per $1,000 of taxable value for counties and a general fund levy limit of $8.10 per $1,000 of taxable value for cities. The levy rate, which is the tax amount per $1,000 of assessed property value, is calculated by dividing the required property tax revenue by the total taxable value of all properties in the jurisdiction. Assessments are limited via the “rollback” system, a proportional reduction in taxable value that applies uniformly to all properties in the state.

The Rollback System

The rollback system for property assessments in Iowa was introduced in 1978 as a response to the high inflation rates of the 1970s, which caused property values and, consequently, property taxes to increase significantly. Iowa law currently limits statewide growth in taxable value due to revaluation of existing property to no more than 3 percent per year.

To this end, the rollback system works by applying a percentage, known as the rollback percentage, to the assessed value of a property to determine its taxable value. This percentage is calculated annually by the Iowa Department of Revenue and varies for different property classes: residential, agricultural, commercial, and industrial. The rollback percentage ensures that only a portion of the assessed value is subject to taxation, effectively capping the growth of taxable values. For example, if a residential property has an assessed value of $500,000 and the rollback percentage for that year is 55 percent, the taxable value of the property would be $275,000. This means that the property owner would only pay taxes on $275,000 instead of the full assessed value of $500,000.

Table 4. Rollback Rates for FY 2026

| Category | Rollback |

|---|---|

| Agricultural (excluding agricultural dwellings) | 73.8575% |

| Residential (rural and urban—including agricultural dwellings) | 47.4316% |

| Commercial Realty | |

| Property of value < $150,000 | 47.4316% |

| Property of value > $150,000 | 90.0000% |

| Industrial | |

| Property of value < $150,000 | 47.4316% |

| Property of value > $150,000 | 90.0000% |

| Railroad Property | |

| Property of value < $150,000 | 47.4316% |

| Property of value > $150,000 | 90.0000% |

| Utility Property | 100% |

The rollback system also includes a provision known as the “ag tie,” which links the growth of residential and agricultural property values. Under this provision, the annual growth in one class cannot exceed that of the other, ensuring that both property classes experience the lower of the two value increases, not to exceed the statutory limit. Historically, agricultural values have not been limited by residential property, but residential properties have been assigned a lower taxable value due to slower growth in agricultural property values.

Crucially, the rollback is based on statewide values, not county-level valuations. But each taxing jurisdiction’s property values will rise (or even fall) at different rates. If some jurisdictions see valuation declines, others rise slightly, and some skyrocket, rollbacks on state averages will reduce collections in the low-growth jurisdictions while still allowing substantial increases in areas where property values have soared. Because Iowa rates are set by budgets, those low-growth areas will sometimes (if not cap-constrained) impose higher mill levies that ensure consistent revenues despite the rollback. Meanwhile, the high-growth counties, even if they can’t raise rates any higher due to caps, will collect much more because statewide averages are inadequate to their situation.

That’s exactly what has been happening in Iowa for years, and it’s why overall tax collections appear stagnant even as many homeowners and other property taxpayers have experienced significant increases. The rollback system also has the effect of continually shifting more of the burden of the property tax to commercial and industrial property.

2023 Reforms

In 2023, Iowa made significant amendments to its property tax system to provide relief and improve transparency via HF 718.[14] One of the key changes was the consolidation of 15 existing levies available for cities into a general fund system, which simplifies the tax structure. The amendments also hard-capped city levy rates at $8.10 per $1,000 of taxable value and county general services at $3.50 per $1,000 of taxable value. Additionally, counties’ rural services were capped at $3.95 per $1,000 of taxable value.

Prior to the 2023 legislation, approximately 30 counties used Iowa Code §331.426 (Additions to Basic Levies) and exceeded the cap of $3.50. These provisions to exceed the cap are now repealed. The hard limits apply from FY 2029 onwards. In the interim, for fiscal years 2025 through 2028, the legislation allows cities and counties an adjusted general basic levy rate based on the current year assessments and levy rates to account for the allowances and additions provided under prior law.

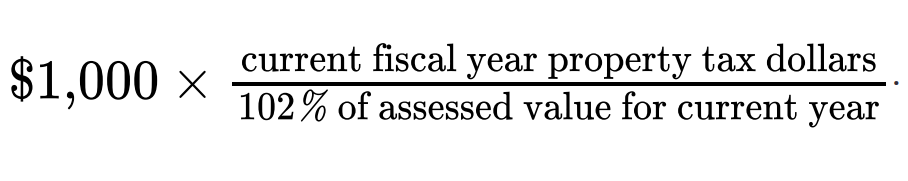

For these intervening years, if total assessed value for the budget year is between 103 percent and 106 percent of assessed value for the current fiscal year, the Adjusted General County Basic Levy Rate (AGCBLR) for counties is reduced, per $1,000 in taxable value, to:

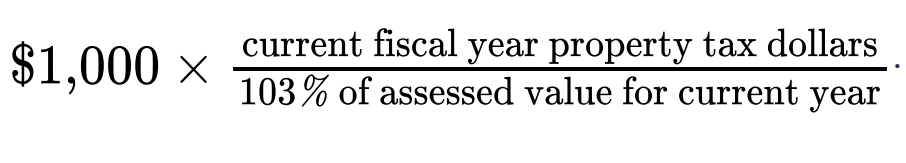

If total assessed value for the budget year is equal to or exceeds 106 percent of assessed value for the current fiscal year, the AGCBLR is reduced to a rate per $1,000 of assessed value equal to

Similar limits apply to city and rural levies, with no reductions if the growth in assessments is below 3 percent from year to year.

Unlike the rollback, these limits are imposed at the county level, which makes them considerably more effective at constraining runaway property tax growth. Notably, however, these limits, while meaningful, are not linear. For instance, at initial assessed value growth a hair under 6 percent, the rollback would limit taxable growth to about 4 percent, whereas if the assessed value growth ticked up slightly and hit 6 percent, the larger rollback would kick in, limiting taxable growth to 3 percent. The limit, moreover, cannot exceed 3 percent—no matter how much county property values increase. There is no upper bound on potential increases, just a rollback of up to 3 percentage points.

The legislation also requires cities and counties to use excess revenues for property tax buydowns, determined by the annual growth in their revenue. Furthermore, the amendments introduced several transparency requirements for local governments’ spending and debt plans. This includes mandating subdivisions to hold a public hearing on proposed property tax amounts for the budget year. This public hearing is separate from any other budget meeting. After the hearing, the governing body may decrease, but not increase, the proposed property tax amount included in the budget.

Iowa now also has a “Truth in Taxation” provision, requiring mailings to property owners with specified assessment, tax, and budget information, including property tax dollars and rates for the current fiscal year and proposals for the upcoming budget year. Statements of explanation for any increases in property tax revenues and examples of residential and commercial property tax obligations are also required. The law also requires the governing body to include specific information on debt obligations in the County or City’s annual financial report, beginning with the annual financial report filed by December 1, 2025. If bonds are to be issued, effective the previous fiscal year, HF 718 requires disclosure of an estimate of the annual increase in property taxes as the result of the bond issuance on a residential property with an actual value of $100,000.

HF 718 also introduced a new homestead exemption for property owners older than 65 years, in addition to the existing Homestead Credit. Qualifying property owners will now be provided with an exemption of $3,250 in taxable valuation in FY 2025 and $6,500 of taxable valuation in FY 2026 and each subsequent year. The law also expanded property tax exemptionA tax exemption excludes certain income, revenue, or even taxpayers from tax altogether. For example, nonprofits that fulfill certain requirements are granted tax-exempt status by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), preventing them from having to pay income tax. allowed to veterans from $1,852 to $4,000 from FY 2025 onwards. Costs of both these exemptions are to be absorbed by the local taxing entity and would not be part of the state budget for property tax relief.

For FY 2028 and thereafter, the new $3.50 cap will be in place, and these temporary, imperfect levy limits will no longer be operative—even though the conditions necessitating them will continue to exist. In other words, HF 718 uses levy limits primarily as a phase-in mechanism for the lower cap, rather than as a long-term way to ensure that property tax bills do not continue to grow too fast due to regional variations in valuation increases. The new law provides important relief mechanisms—but because it coexists with the statewide rollbacks, uses incomplete levy limits, and allows those limits to expire, it is insufficient to tackle the problem for the long term.

Implementing Levy Limits

In response to rising property tax bills, some states have implemented assessment limits, which constrain valuation growth for individual parcels, typically resetting upon sale. These policies, while superficially attractive, create a lock-in effect whereby existing homeowners are strongly incentivized to remain in the same home for as long as possible. They discourage new construction, shift costs to new and younger homeowners and would-be homebuyers, and create substantial inequities, with virtually identical houses on the same street often facing radically different tax bills.[15]

Fortunately, Iowa lawmakers have largely focused on a much more promising solution: levy limits. HF 718, while far from ideal, employed a variation on levy limits, and several current proposals seek to build on that foundation.

Unlike assessment limits, levy limits (also called revenue or collection limits) are concerned with the actual amount of revenue raised, imposing rollbacks or obligating rate reductions to ensure that collections do not increase in aggregate above a given amount. Individual owners may experience an increase or decrease in tax liability based on changes in rate or assessed value, but aggregate collections from the same set of properties are constrained. Whereas assessment limitations only allow a tax increase above a given threshold based on intentional policy action (a rate increase) and rate limitations only permit them when driven by rising housing values, a levy limit permits greater variation but all within the context of a hard revenue limit.

Levy limits do not necessarily protect all taxpayers individually from tax increases. Policymakers remain free to adjust rates within the overall revenue cap unless separately constrained by a rate limit (which Iowa has, with a cap phasedown in place), and if certain properties increase in value more than others, their property taxes will be higher than those for properties that did not appreciate similarly in value. But they avoid picking winners and losers, avoid creating perverse incentives, and impose an effective constraint on the growth of property taxes.

Levy limits neither reward nor penalize new construction, the choice between moving and staying, or a decision on whether to renovate a home. They keep property tax increases in check without severing the connection between property owners’ tax liability and their relative assessed values.

This turns out to be important. While it’s appealing to promise that no homeowner’s tax bill will rise above some set amount, it’s not really a property tax if it’s no longer tethered to the market value of the property. More valuable properties should face higher property tax bills than less valuable ones, in proportional terms. The key is to ensure that neither property’s taxes skyrocket just because valuations rise.

Imagine two properties in different neighborhoods in the same city, both purchased at the same time for $250,000. One neighborhood takes off, and the home is now worth $500,000. The other neighborhood doesn’t change as much, but since all property values have appreciated, that home’s value increases to $350,000. Setting aside inflation, if property tax rates remain unchanged, one home will see a 100 percent increase in property tax burdens while the other will see a 40 percent increase, neither of which is likely warranted. Mill levies should be rolled back to avoid these large unlegislated increases, which a levy limit would accomplish automatically. But should the house worth $500,000 have the same property tax bill as the one worth $350,000 (the outcome of an assessment limit), or should the home with the higher market value pay proportionally more than the home with a lower value?

This isn’t just a fairness issue. It also affects economic incentives and has a bearing on what the property tax is and does. Assessment limits shift the burden of the tax onto new investment, restricting housing supply and reducing housing affordability. They also sever the link between taxes paid and benefits received, forcing newer purchasers to bear burdens radically disproportionate to the value of services provided. Levy limits, by contrast, keep tax burdens in check without cutting the vital linkage between market value and taxation.

Levy limitation regimes typically allow local governing bodies to ask voters to approve increases above the limit. These voter overrides, however, force the increase to be a conscious choice, and one ratified by the voters, which is markedly different from a hidden, unlegislated tax increase. Levy limits also pair well with Truth in Taxation requirements like Iowa has, which provide more transparency about the cost of a potential property tax change.

Iowa’s current rollback regime, despite different terminology, operates something like a levy limit, but it fails to achieve its intended result because it is implemented at the state level, meaning that millages in every jurisdiction roll back based on the overall projected statewide increase in property tax collections due to rising property values. (It also treats each class of property separately, with different—or no—rollback factors.) This approach makes little sense, as it provides insufficient relief in areas that are growing (and seeing values rise faster than statewide averages), and it creates perverse incentives for localities. The limitation, while established by state law, should be imposed at the level of the responsible taxing jurisdiction.

The appropriate measure for levy limitations is the anticipated tax liability for preexisting property. When property values are rising, the exact same set of properties will have higher tax liability year over year. The goal of a levy limit is to cap the amount of revenue that can be generated from the status quo by reducing millages accordingly. New construction should be excluded, because it appropriately brings in additional revenue, as the additional housing or commercial property creates new costs for the locality.

Policymakers also need to decide on an appropriate annual growth factor for that existing property. Typically, it will be inflation at a minimum, or perhaps inflation plus some additional amount of allowable growth—like 1 or 2 percent growth above inflation. Lawmakers must also decide what spending obligations, if any, can allow increases beyond the growth factor.

Imagine a small jurisdiction with 2,000 homes. (For the sake of simplicity in this example, we’ll only consider homes, though commercial and industrial property matter as well.) In the first year, they collectively bring in $5 million in property taxes at that year’s property tax rates. By the next year, 100 new homes have been built, bringing in an additional $300,000 in property taxes under existing rates. The preexisting 2,000 homes, meanwhile, have seen their assessed values rise, and they are now projected to bring in $5.6 million if rates do not change.

If inflation were at 2 percent and this locality imposed a growth factor of inflation plus 2 percent, then rates would have to be adjusted to ensure that the existing 2,000 homes paid no more than $5.2 million. This would obligate a 7 percent reduction in tax rates. (If, for instance, the rate had been 10 mills previously, it would be about 9.3 mills in year two.) The additional revenue expected from the 100 new homes would not be part of this calculation, though they too would benefit from the lower rate and thus bring in a little under $280,000 rather than $300,000. Overall collections would rise from $5 million to about $5.48 million, whereas they would have risen to $5.9 million absent the limitation.

Many limitation laws stipulate that tax in the amount necessary to service certain debt, or to meet certain obligations, is not subject to the levy limit. This can make sense, but policymakers need to tread carefully if they wish to avoid gutting their own limitations. It may be reasonable to exclude debt service on revenue-producing improvement bonds, for instance, but if all bonds are excluded, this may render the limit ineffective. Iowa has some experience with exclusions that are too broad. It may be necessary to allow taxes to rise above the otherwise limited amount if a locality incurs liability in litigation. It likely does not make sense, however, to allow a wide range of obligations—including pension contributions—to provide end-runs around the limits.

If a jurisdiction were up against a rate cap, local officials would not be permitted to raise the rate above that amount due to rising costs. They would be obligated to find other ways to balance the budget. It is reasonable for levy limits to impose roughly commensurate constraints.

Sometimes, however, a jurisdiction may have good reason to increase revenues above the allowable growth factor. Well-designed levy limits do not prohibit this. They make the increase transparent, and frequently put the decision in the hands of voters, who can decide whether to authorize an override. The beneficial effect of levy limits is to crack down on unlegislated tax increases that result from appreciation in property values, without anyone—local officials or the general public—ever casting a vote to raise taxes.

Finally, in crafting levy limits, lawmakers should avoid allowing a downward ratchet effect during economic downturns and should consider allowing local officials to “bank” some or all of the allowable increase they decline to use.

During a recessionA recession is a significant and sustained decline in the economy. Typically, a recession lasts longer than six months, but recovery from a recession can take a few years. , property values often decline, typically rebounding in a few years. If a levy limit restricted revenue growth as the property market recovered, it could result in far less tax being collected on the same set of properties post-recovery compared to pre-recession. Levy limits are intended to constrain expansionary tax policies; they are not supposed to have a sharply contractionary effect. In designing levy limits, lawmakers should avoid this downward ratchet effect by applying the allowable growth factor against the last highest collections, not the previous year’s collections, when there has been a decline in value.

Sometimes, moreover, local officials may elect not to take advantage of additional revenues. They may choose to reduce rates more than what is obligated by the levy limits, declining to capture the revenue growth allowed by the statewide formula. If the levy limitations are use-it-or-lose-it, this strongly incentivizes jurisdictions to take all allowable growth each year so that they do not reduce their capacity to increase revenues later. To avoid encouraging localities to always max out, lawmakers might consider allowing jurisdictions to “bank” at least some of the unused cap.

Legislative Efforts in 2025

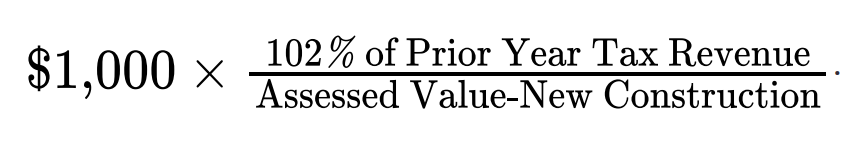

Under companion bills filed in 2025, House Study Bill 313 and Senate Study Bill 1208, Iowa would adopt a 2 percent levy growth limit while phasing out the current rollback regime and accelerating the phaseout of the adjusted general basic levy (AGBL). Beginning with Fiscal Year 2027, the following formula would be used to roll back mill levies in response to rising property values, kicking in whenever assessed value of existing properties rises more than 2 percent:

Crucially, the legislation phases out the rollback provision for property assessments, gradually increasing the taxable value ratio to 100 percent by 2029. This is an important piece of the puzzle, as the current rollback system creates distortions and fails to prevent dramatic tax increases in some areas, but it does reduce tax burdens (if inefficiently). Retaining it would keep its distortionary effects in place. Repealing it on a standalone basis would cause tax burdens to rise. Conversely, phasing it out after a levy limit is in place allows a transition from one system to the other, with the levy limit itself working to keep the rollback’s reductions in place.

The bill also shifts foundational school funding from a $5.40 per $1,000 statewide property tax levy, currently covering about 88.4 percent of the funding formula alongside state aid, to full reliance on state general funds by 2031, reducing the school district foundation levy to $2.97 per $1,000 by fiscal year 2031. Additionally, under the legislation, capital improvements to agricultural land that do not enhance productivity would not increase agricultural taxable assessments, instead being valued as residential property.

The legislation also replaces the homestead credit with a homestead exemption available to all, starting at $4,680 in 2026 ($6,500 for those 65 or older), rising to $25,000 by 2029, while phasing out the credit entirely by that year. Disabled veterans retain their credit but must apply separately, while serving military and honorably discharged veterans will see their additional exemption rise to $7,000 by 2027.

While the homestead credit would be reimbursed by the state government to the local taxing authorities, the exemptions would have to be absorbed by the county, city, and school districts. Additionally, the bill stipulates that proceed from bonds, if approved by the constituents, may not be used for general operations or to compensate for these exemptions.

This legislation, as introduced, gets some big things right: a levy limit rather than an assessment limit, and the phaseout of the existing rollbacks. The system also, appropriately, excludes new property in calculating the new mill levy. And it incorporates voter overrides from the 2023 reforms, applying them to the new limits. There are, however, several other components that Iowa lawmakers may wish to consider.

First, lawmakers may wish to incorporate inflation into the levy limit. This ensures that the limits do not reduce tax collections in real terms when inflation is high, though of course taxpayers often feel a pinch at the same time. The 2 percent growth cap chosen may reflect a desire to restrict real growth from exceeding an ordinary level of inflation (with no additional growth allowance), but recent years have demonstrated that inflation can well exceed that.

Second, while lawmakers may be happy to just keep property tax burdens in check, they shouldn’t rule out the possibility of a local government choosing to cut property taxes—and probably didn’t intend to. A formula that, whenever assessed value growth exceeds 2 percent automatically sets the mill levy to capture 102 percent of prior year’s revenues from existing property (plus whatever is generated by new property) may deny local governments the opportunity to voluntarily set a lower mill levy, which they can accomplish under the current system by adopting a budget target that yields a tax cut.

While some provisions of the proposed legislation are drawn to Iowa Code Section 331.423, which clearly establishes the limited levies as maximum rates, the revisions and additions to Section 384.1 appear to make a likely inadvertent break with establishing maximums and instead might be interpreted as obligating the rate calculated by the new limitation regimes. A well-designed levy limit shouldn’t force tax cuts on local governments, but it shouldn’t prevent them, either. To encourage localities not to treat increases as use-it-or-lose-it, moreover (and therefore always use it), lawmakers may wish to allow some portion of unused increases to be “banked.”

Third, lawmakers may want to recession-proof their levy limits by ensuring that a temporary decline in property values does not suppress tax revenues even after the housing market has recovered. Imagine, for instance, that home prices declined by about 20 percent, as they did during the Great Recession, then recovered a few years later. It is wholly appropriate that these initially lower assessed values would yield lower tax bills, but there is no logical reason why a levy limit should delay the recovery of tax revenues for years after housing values have recovered, as would be the case if a 2 percent (or any other) annual cap were imposed linked to prior year tax collections.

In other states, levy limits tend to look back to the prior year’s allowable limit, not prior year tax collections as such. (Actual tax collections would be appropriate to set the first-year baseline, however.) If, say, Dubuque County raises $40 million in property taxes in year 1, the next year’s allowable limit (at 2 percent) would be $40.8 million, plus new construction. If an economic decline meant that actual market values dropped to $35 million that subsequent year, the allowable limit would still be $40.8 million, and would continue to grow accordingly, so that when, eventually, property values recover, the tax collection authority is not based on 2 percent annual growth recovery from the reduced $35 million valuation. Especially absent some inflation adjustment, every economic downturn would leave Iowa jurisdictions in a hole from which they would never quite recover.

Conclusion

After decades spent relying on rollbacks and other fixes that didn’t quite work, Iowa lawmakers are on the right track, exploring meaningful levy limits to replace and dramatically improve upon Iowa’s faulty rollback system. With such an important change to Iowa’s property tax system, it’s important that lawmakers get the details right. It’s also important that lawmakers acknowledge and address the very real concerns of homeowners who have seen their tax liability soar despite the flawed protections embedded in the existing system. That system has yielded relief, but inconsistently and incompletely. Phasing out the rollback and replacing it with well-designed levy limits will address the inequities of the rollback (across geographies and classes of property) and constrain the growth of property tax burdens across all 99 counties. That’s reform worth doing.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeReferences

[1] See, e.g., Jens Arnold, Bert Brys, Christopher Heady, Åsa Johansson, Cyrille Schwellnus, and Laura Vartia, “Tax Policy for Economic Recovery and Growth,” Economic Journal 121:550 (2011): F59-F80; Santiago Acosta-Ormaechea and Jiae Yoo, “Tax Composition and Growth: A Broad Cross-Country Perspective,” IMF Working Paper, October 2012; Dagney Faulk, Nalitra Thaiprasert, and Michael Hicks, “The Economic Effects of Replacing the Property Tax with a Sales or Income Tax: A Computable General Equilibrium Approach,” Ball State University, Department of Economics, Working Papers, June 2010; and Stephen T. Mark, Therese J. McGuire, and Leslie E. Papke, “The Influence of Taxes on Employment and Population Growth: Evidence From the Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Area,” National Tax Journal 53:1 (2000): 119.

[2] See generally, Joan Youngman, A Good Tax: Legal and Policy Issues for the Property Tax in the United States (Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2016).

[3] For a broader discussion of property taxes and property tax limitations, from which this section is adapted, see Jared Walczak, “Confronting the New Property Tax Revolt,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 5, 2024, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/state/property-tax-relief-reform-options/.

[4] Iowa Department of Management, Property Tax Rate Files (multiple years), https://dom.iowa.gov/local-government/property-tax-tax-replacement#property-tax-rate-files; Tax Foundation calculations.

[5] US Federal Housing Finance Agency, “All-Transactions House Price Index for the United States,” https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/USSTHPI; and Id., “All-Transactions House Price Index for Iowa,” https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/IASTHPI, via FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

[6] Iowa Department of Management, Property Tax Rate Files (multiple years); Tax Foundation calculations.

[7] US Census Bureau, “Annual Survey of State and Local Government Finances,” 2022, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/gov-finances.html.

[8] Id.

[9] US Census Bureau, “American Community Survey,” 2022, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs; Tax Foundation calculations.

[10] Iowa House File 654, Iowa General Assembly, Sixty-Fourth G.A., First Session (1971).

[11] Iowa House File 535, Iowa General Assembly, Seventy-Third G.A. (1989).

[12] Iowa House File 2663, Iowa General Assembly, Eighty-Second G.A. (2008).

[13] For a general summary, see Winneshiek County, “What is Equalization? – Winneshiek County,” 2022, https://winneshiekcounty.iowa.gov/departments/assessor/what-is-equalization.

[14] Iowa House File 718, Iowa General Assembly, Ninetieth G.A. (2023).

[15] For more on assessment limits, see Jared Walczak, “Confronting the New Property Tax Revolt.”

Share this article