Key Findings

-

The country of Georgia has successfully implemented dramatic tax reforms over the last two decades.

-

The system has moved from one with lots of complexity to one that promotes investment and economic growth.

-

The main features of the current system include a 20 percent value-added tax (VAT), a flat personal income taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. at 18 percent, and a corporate profits tax of 15 percent that exempts reinvested earnings.

-

Georgia also has a law in place that limits government debt and spending levels.

Dedication

This paper is dedicated to the successful story of Georgian tax reforms, to Kakha Bendukidze and Mart Laar and all others who contributed all their knowledge and experience to its success.

Introduction

The Georgian people decisively and proudly abandoned a socialist economic system, and since 1990 have faced new challenges to reorganize the nation’s economy into a market one. With new institutional demands, Georgia needed to adopt a tax system to ensure the government’s operations. Such a system needed to be successful both for economic development and for sustainable state revenues. Several failures prior to 2004 led Georgia to abandon its previous way of taxation and succeed with simplifying, cutting rates, and digitalizing the system. Tax cuts accelerated the economy and the government’s revenues. This important change was possible only after taking full responsibility of economic policy after several years of crisis and stagnation, a high level of corruption and government mismanagement, and despite inaccurate foreign advice.

Prior to the Reforms

Georgia had been using the Soviet tax system after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 until 1994, when it adopted its own tax laws. In 1997 it implemented a tax code based on the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) proposed tax system for nations transitioning from communism towards market economies.[1] This system was very artificial and did not reflect local realities, intending only to support government tax collection efforts.

From that time, the tax code consisted of several different taxes, the total burden of which could reach as high as 50 percent. This tax system immediately became an opportunity for lobbying and seeking privileges. The complexity of the tax code became a reason for tax avoidance, bred corruption, and resulted in taxpayers being overly burdened.

From 1997 to 2003, the government made more than 300 amendments to the tax code, with more than 2,000 clauses. It was impossible to follow how and when to pay taxes according to the tax code. Tax authorities also had trouble collecting taxes for the same reasons. Instead, both sides became involved in unofficial tax payments—some in the form of lump sum payments and others in the form of bribes. Therefore, the number of taxes and their rates became disconnected from actual tax collections. Instead, the tax system became an extreme burden to taxpayers and a drag on the Georgian economy.

This environment attracted very risky people who often resorted to bribery and breach of contract, even if it meant being imprisoned. Hiding business activities was the rule, not an exception. Labor reimbursement was also taxed very heavily at 20 percent. In fact, labor income was supposed to be taxed at rates from 12 to 20 percent in a progressive manner, but this was only a formality, and everybody paid 20 percent. In addition, every worker’s salary was also taxed, with social insurance taxes of around 31 percent. This meant around 60 Georgian Lari of tax was paid for each 100 Lari in salary.[2] In many cases employers would pay dividends to their workers instead of salaries, which allowed them to pay only 39 Lari in taxes per 100 Lari. For instance, a bread factory in Kutaisi employed 500 workers to whom the factory owners paid only dividends.

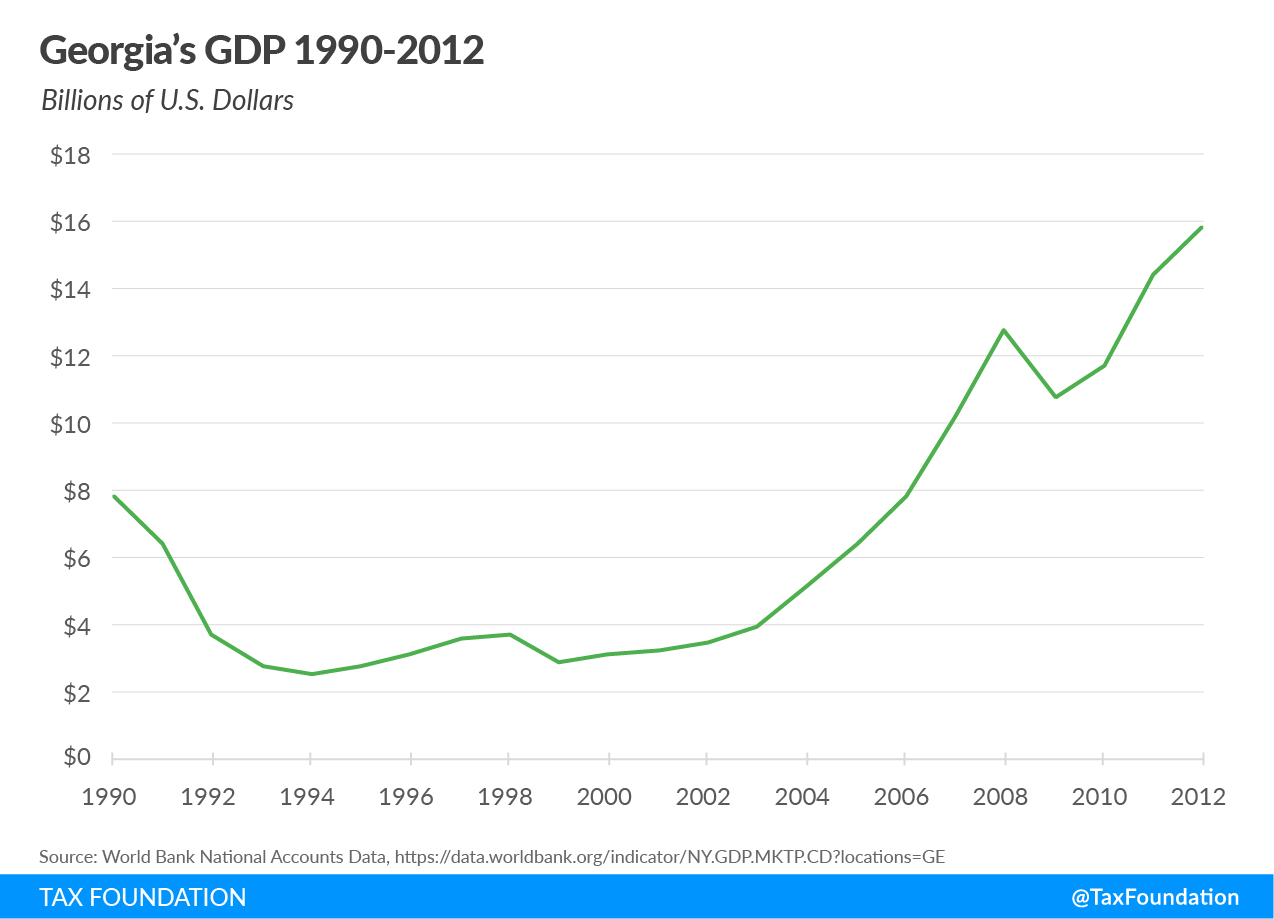

A poor and burdensome taxation system along with extremely limited economic freedoms (Georgia’s rank in the Economic Freedom Index in 2002 was 93rd) resulted in economic depression, which lasted many years after the collapse of Soviet Union. GDP per capita couldn’t rise to even one-third of Soviet levels, and stayed at a level below $1,000 U.S. Figure 1 shows the decline and then the rise of Georgia’s economy[3]:

The Reform Effort

In 2001, the Georgian government decided to reform the tax system. Together with some industrial groups, the government asked local experts to create a draft of a new tax code. The group of six (of which the author of this article was a member) was led by a Georgian economist, the late Niko Orvelashvili, who enthusiastically worked to recreate Georgia’s tax system. The group of experts consulted with hundreds of specialists of taxation, customs, accounting, and law. The group created a conceptual framework for a new code, which was meant to establish an environment of free entrepreneurship, legality, and efficiency.

The group proposed the following principles and goals for the reform effort:

- Simplifying the tax system radically by decreasing the number of taxes and tax rates, thereby cutting the total tax burden in half or more, and making tax payment easier, thereby eliminating the need to pay bribes and reducing risk overall;

- Eliminating double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. , abuse of tax rules by the government, and all privileges and special rules for any sectors or companies;

- Eliminating special taxes (social, road, environment);

- Tax rules should correspond to the human rights protections enshrined in Georgia’s constitution;

- The burden of proof in tax disputes should reside with the government, not the taxpayer, as is the case in all other disputes;

- All tax rules should be clearly described in the tax code;

- Tax rules should be clear, long-run, rational, stable, and predictable.

The prepared draft passed one hearing but was not adopted because of the opposition of special-interest groups.

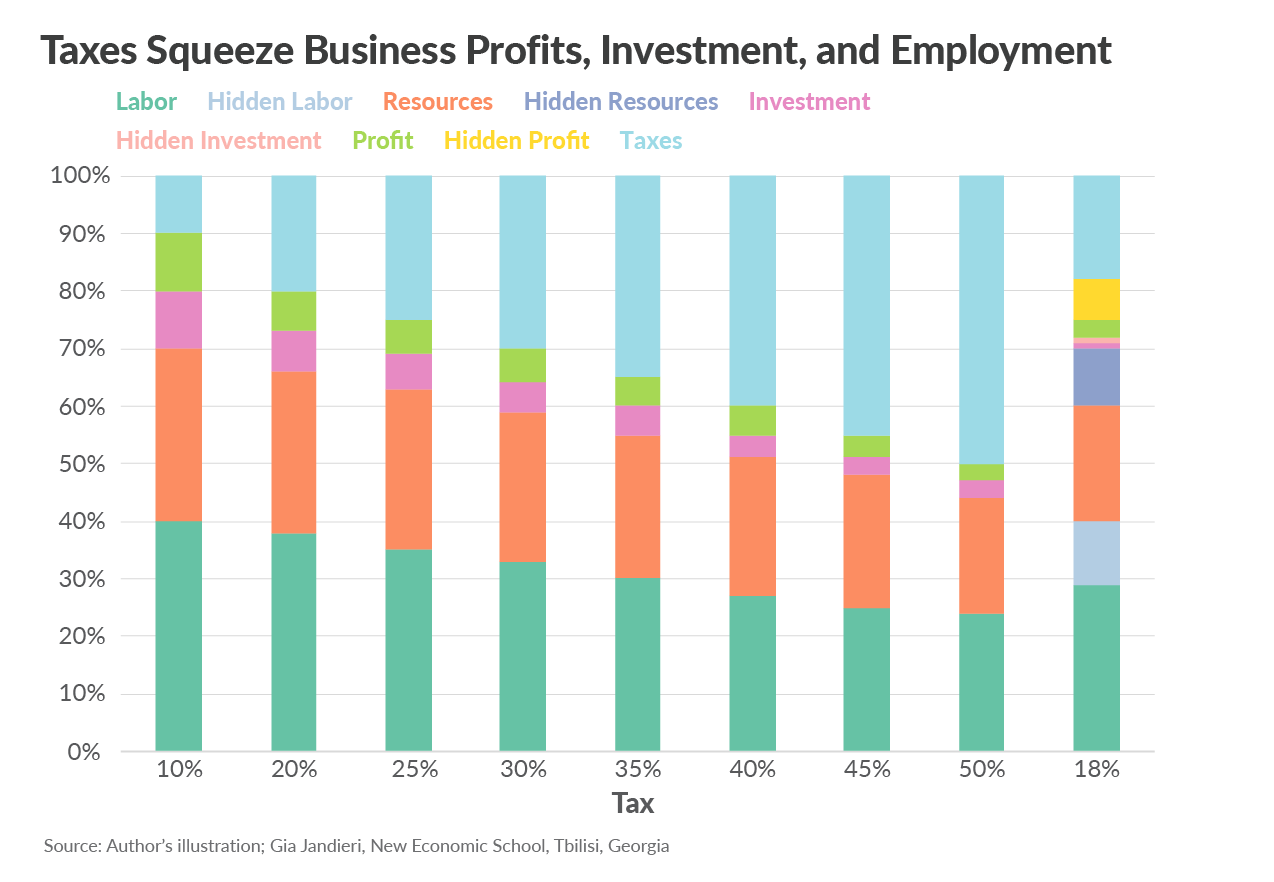

Illustration: Taxes Squeeze Business Profits, Investment, and Employment

The chart below was developed by the author of this article in 2001 to demonstrate to political leaders in Georgia how increasing the tax burden has the potential to decrease business investment, jobs, and even government revenues.

This illustration was influential in convincing Georgian officials that systems with overly burdensome taxes can create incentives to hide business income and avoid tax authorities.

Note: This chart was used purely for illustrative purposes and does not reflect actual data.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeFollowing the Rose Revolution in 2003, the new government in 2004 swore to improve the business environment, and in 2005 implemented the new tax code. It used almost all the above principles. The following table shows which taxes remained after the reform and how rates were changed.

|

Source: Tax Reforms in Georgia, Ministry of Finance of Georgia, https://www.imf.org/external/np/seminars/eng/2011/revenue/pdf/rusuda.pdf |

||

| Tax | Old Rate | New Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Personal Income | 20% progressive | 20% flat |

| Profit (Corporation) | 20% | 15% |

| VAT | 20% | 18% |

| Excise | Imposed on many goods | Imposed only on 4 types of goods (cars, fuel, alcohol, tobacco) |

| Social | 31% | Eliminated in 2008 |

| Property | Several rates | 1%, with possible discounts[4] by local authorities |

| Customs | 0%, 12%, 20%, 32%, or higher | 0% or 12%, mostly 0% |

The tax reform continued with several improvements. One of them is the rule of 100 percent depreciation of purchased assets. This investment-friendly rule was later strengthened by another rule—the so-called Estonian model of not taxing profit if re-invested (in force from 2017).

The Results

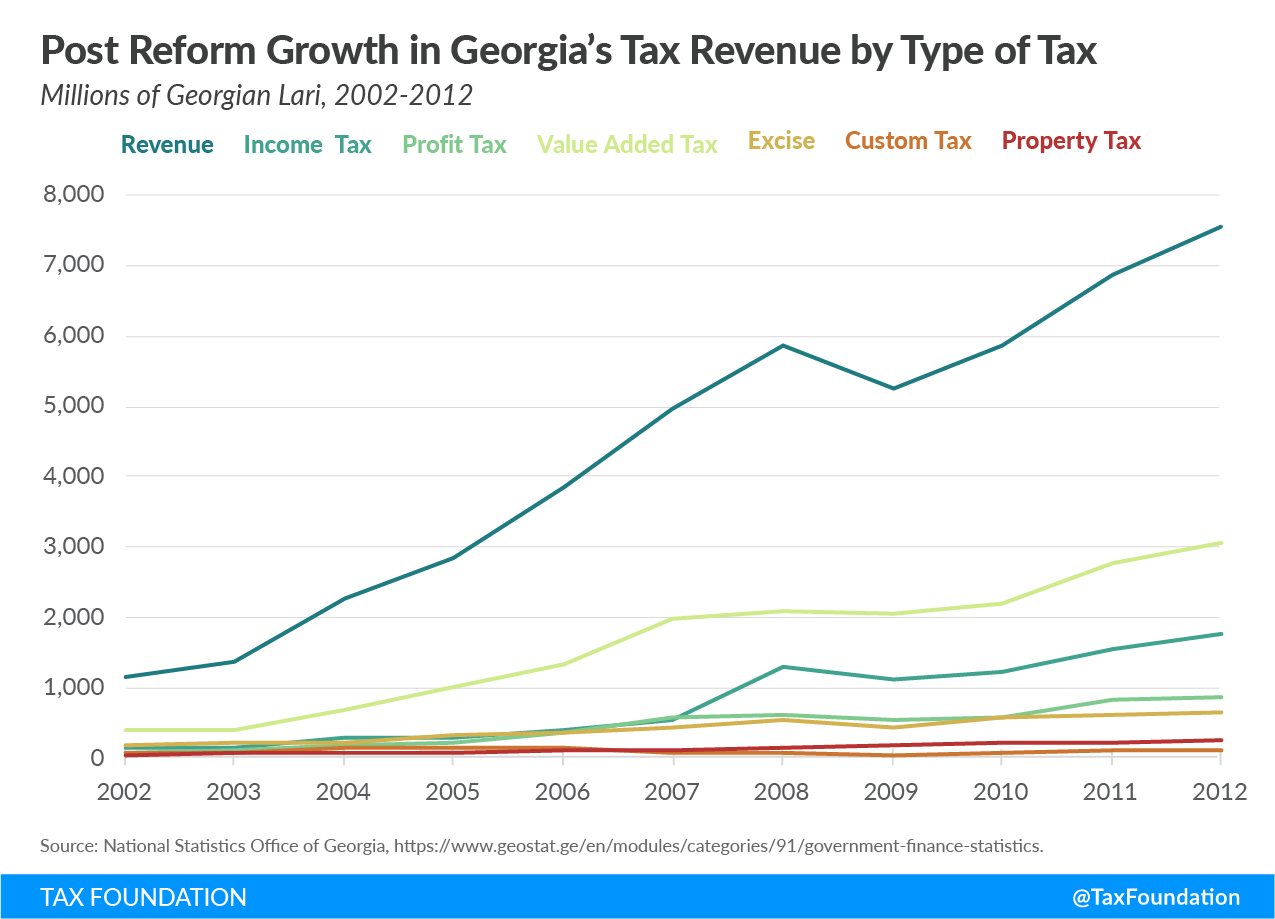

Implementation of the new system was ensured by the work of the former minister of Reforms Coordination, the late Kakha Bendukidze. The fiscal outcomes of the reforms were incredible, though predictable. All types of taxes (except customs tax) increased the related state revenues: Value-Added Tax revenues increased by more than seven times, personal income tax revenues increased by more than eight times, and profit tax revenues increased by 10 times.

Figure 3 illustrates this tendency.

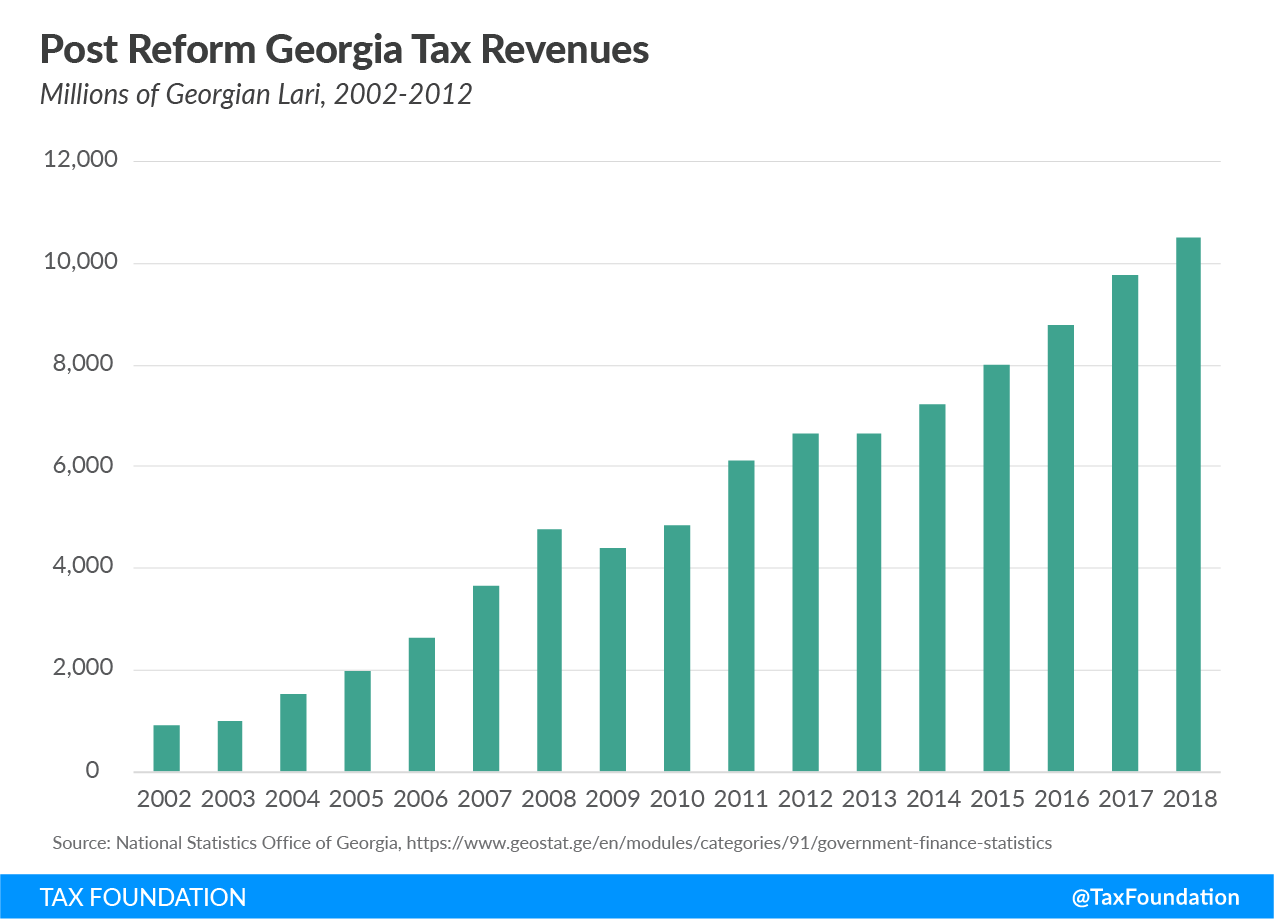

The improvement of the economy was tremendous. GDP doubled during the first four years and tripled in the first eight years of the reforms (despite the decline in 2009). The success was the result not only of tax reform but also of more complex and wider ranging reforms, including deregulation, liberalization, and limiting of government powers.

The supply-side effects of the tax cuts further increased state revenues as shown in Figure 4. Wage growth also accelerated following the reforms.[5]

The tax reform was crowned by the Economic Liberty Law of 2011. This amendment to the Georgian Constitution, inspired by Bendukidze, requires a nationwide public referendum to support any increase of tax rates or implementation of a new tax. Together with a spending limitation—30 percent of GDP of all government budgets combined—this improved the sustainability of the reforms and framed the limits of government functions. The law also requires public debt and budget deficit ratios be limited to 60 percent and 3 percent of GDP, respectively. This has already played a decisive role in limiting the spending abilities of the government. The recent ruling coalition promised voters many new spending initiatives which would be beyond the government’s budget capacity, and the new majority in power also intended to implement new regulations and functions, but the spending cap slowed this tendency.

The IMF and other international organizations never supported the tax reforms, including the Economic Liberty Law, though many of them claim their general support of policies of fiscal discipline. Recently, the government of Georgia made a step to eliminate the Economic Liberty Law after 12 years—which could open the way for future manipulations and abuse. The IMF was again silent on this step and showed its preference in such trends.

Conclusion

The success of the tax reforms in Georgia is very strong evidence that even nations with a bad historical experience and the most intense economic crises can solve their problems using free market solutions. The story of Georgia should be an example to all developing nations that any country with the will to do so can take charge of its own tax system and, without the aide or interference of international organizations, create the conditions for economic growth and prosperity.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe[1] IMF Legal Department, “Tax Code of Republic of Taxastan,” Sept. 29, 2000, https://www.imf.org/external/np/leg/tlaw/2000/eng/stan.htm.

[2] Recent exchange rates show 1 Georgian Lari = $0.36 USD.

[3] The World Bank, “World Bank National Accounts Data, GDP (current US$),” https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=GE.

[4] Property tax in Georgia is a local tax, but it is limited. Local authorities are given power to reduce the tax by multiplying the tax to a coefficient that can be from 0 to 100%, which means it can be 0 if decided, but cannot be more than 1% if the coefficient is 100%.

[5] National Statistics Office of Georgia, “Wages: Average monthly nominal earnings, Gel,” https://www.geostat.ge/en/modules/categories/39/wages.

Share this article