Key Findings

- One year after the enactment of the InflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. Reduction Act (IRA), the law’s complicated taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. increases on large corporations, particularly the minimum tax on book incomeBook income is the amount of income corporations publicly report on their financial statements to shareholders. This measure is useful for assessing the financial health of a business but often does not reflect economic reality and can result in a firm appearing profitable while paying little or no income tax. , have resulted in extraordinary implementation challenges and taxpayer confusion, with many questions left unresolved. Payments for both the minimum tax and the stock buyback tax are currently on hold until the IRS issues further guidance.

- The law’s subsidies for green energy, in the form of several tax credits with novel features including transferability and monetization, have proven attractive to taxpayers, leading to escalating budgetary costs approaching $1 trillion over the next decade. Among other things, this means the IRA as a whole likely worsens deficits.

- Congress should reconsider key elements of the IRA, including the book minimum tax and the green energy credits, with an eye towards simplification and fiscal responsibility.

Table of Contents

Introduction

On August 16th last year, President Biden signed into law the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the most substantial federal tax legislation since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017.[1] The IRA is an ambitious effort to achieve multiple, competing goals. As the title implies, the law was intended to reduce inflation by reducing deficits, primarily via new taxes on large corporations in the form of a minimum tax on financial (or book) income, a stock buyback tax, and an excise taxAn excise tax is a tax imposed on a specific good or activity. Excise taxes are commonly levied on cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, soda, gasoline, insurance premiums, amusement activities, and betting, and typically make up a relatively small and volatile portion of state and local and, to a lesser extent, federal tax collections. on drug companies that enables the government to control drug prices. As well, the law provides a substantial boost for the IRS budget, mainly to increase enforcement and tax collections.

The IRA was also meant to address climate change through massive subsidies for green energy on an unprecedented scale, primarily in the form of generous and largely uncapped tax credits. In addition, many of the credits are designed to shift production to domestic sources, boost unionized labor, and favor communities traditionally dependent on fossil fuel production.

As a byproduct, the IRA introduces a new set of complexities in the tax code, leading to implementation challenges, reams of regulatory guidance and taxpayer comments, and unresolved questions remaining more than seven months after the law went into force.[2] The following analysis provides a snapshot of what we know about the IRA one year after enactment in terms of implementation of the major provisions, outstanding taxpayer concerns, and fiscal and economic impacts.[3]

Book Minimum Tax

The new 15 percent minimum tax on book income (also known as the corporate alternative minimum tax, or CAMT) is not as simple as it may sound. The 15 percent minimum tax applies to corporate book income, with certain adjustments, for corporations with profits over $1 billion, effective for tax years beginning after December 31, 2022. As a new tax on a new tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. (adjusted financial statement income), it introduces a variety of problems and unintended consequences, embroiling taxpayers and administrators in several knotty issues that remain unresolved. Implementation has been challenging and initial regulatory guidance released by the Treasury Department and IRS addressed only a limited set of issues, leaving more questions than answers for taxpayers and practitioners as detailed in hundreds of pages of comment letters, some of which are summarized below.[4]

Academic accounting and policy experts have been clear in warning about the dangers of using book income for tax purposes.[5] Many of the challenges stem from the fact that financial accounting and tax accounting serve different purposes, the former to provide information to shareholders and other investors on the financial health of companies based on standards of financial accounting and the latter to determine tax liability under the rules established by Congress. Squaring this circle is proving to be an overwhelming conundrum for the lawyers and economists at the Treasury Department and IRS tasked with drafting guidance for the book minimum tax (BMT), who are more familiar with tax accounting than financial accounting.[6]

One key difference between tax and book accounting is the treatment of capital investment, such as equipment purchases. For book purposes, capital investment expenses are depreciated and recorded over the life of the asset, following the matching principle in accounting of matching expenses with associated income. For tax purposes, Congress has long recognized using schedules that expedite depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. deductions will increase incentives to invest, leading to many tax provisions for accelerated depreciation, such as Section 168(k) bonus depreciationBonus depreciation allows firms to deduct a larger portion of certain “short-lived” investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings in the first year. Allowing businesses to write off more investments partially alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. for short-lived assets such as equipment. Reflecting ongoing concerns about investment impacts, just days before the passage of the IRA, Congress amended the BMT to allow taxpayers to use tax depreciation rather than book depreciation in determination of adjusted financial statement income (AFSI) subject to the tax, but only for Section 168(k) property.

While the change reduced the economic harm of the tax, it also added a substantial amount of complexity and compliance cost for taxpayers. Book accounting does not track Section 168(k) property, so taxpayers will be required to assemble and track the property separately, including its tax basis, using book accounting asset categories. The process is further complicated by the start date of the BMT (with the initial AFSI determination period beginning in 2020), which penalizes taxpayers who utilized bonus depreciation prior to 2020.[7] Because of depreciation and other adjustments to financial statement income, taxpayers now have to keep three sets of books in order to comply with the BMT: one for financial purposes, one for regular corporate tax purposes, and one for the BMT.

Another major difference between tax and book accounting is the treatment of gains and losses on assets. For tax purposes, gains and losses on assets are generally determined based on the realization principle, that is, based on a market transaction such as a sale. In contrast, financial books sometimes track the unrealized gains and losses of assets on a mark-to-market basis, which can result in large differences in the timing of income recognition. The statute and subsequent guidance recognized this mismatch in some but not all cases, allowing taxpayers to exclude from AFSI unrealized gains and losses for certain assets, such as those held in defined benefit pension plans. Taxpayers have noted this distorts investment decisions by creating a tax incentive to invest in excluded assets and have requested a comprehensive exclusion from AFSI for all unrealized gains and losses for book purposes and other items of income that are not included in regular taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. .[8]

A third major difference is that tax accounting is defined by specific rules and restrictions while book accounting allows more room for discretion and judgment calls on the part of the company. One practical implication in regard to the BMT is that where there are ambiguities (and there are many), taxpayers will be able to make book accounting decisions that lower tax liability. When a similar tax was introduced for two years in the 1980s, evidence indicates companies did in fact lower book income in response to the tax.[9] As accounting and policy experts have noted, this leads to fundamental questions about the soundness of the BMT as a revenue raiser or as a tax that ensures in any real sense a certain level of minimum tax. The same experts have also warned that by creating an incentive for taxpayers to manipulate financial income to reduce tax liability, the BMT could undermine the credibility and usefulness of company financial information on which our capital markets depend.[10]

Taxing book income is leading to a variety of implementation challenges and taxpayer confusion beyond the areas of concern highlighted above. As with the issue of unrealized gains and losses, regulatory guidance and taxpayer comments to date point to several issues that may be unresolvable without generating tremendous compliance costs for taxpayers or limiting the tax in such a way that it fails to generate any substantial amount of revenue for the federal government.[11]

For instance, one set of outstanding issues revolves around which financial statements and standards apply for reporting AFSI. For multinational enterprises and especially inbound companies (that is, foreign-headquartered companies with U.S. affiliates), some of their operations may report financial income under the U.S. accounting standard (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, or GAAP) while others may report income under the international standard (the International Financial Reporting Standards, or IFRS). The statute indicates taxpayers should prioritize GAAP accounting over IFRS and other standards, but that still leaves questions about how to match and blend the standards for different operations on a consolidated basis.[12]

A related problem is the mismatch between consolidation rules for book and tax income.[13] U.S. GAAP standards consolidate entities in certain fact patterns where tax does not (e.g., partnerships can be consolidated under U.S. GAAP but not tax rules).[14] A particular issue with the BMT is that the current statute and guidance could result in the double counting of income from majority-owned foreign corporations (controlled foreign corporations, or CFCs); taxpayers have therefore requested a broad exclusion of CFC dividends from AFSI.[15]

Insurance companies face a unique set of issues and use a special set of accounting rules, leading the Treasury Department to release 21 pages of specific guidance for the insurance industry that addresses several issues and allows taxpayers to exclude many items of income for BMT purposes.[16] These questions are not unique to the insurance sector.

Another outstanding set of issues relates to partnerships that flow up to corporations subject to the tax.[17] The biggest open question is when—and how much—partnership income is required to be included by related corporations (direct corporate partners, indirect corporate partners, and corporations that are part of the same controlled group). While the BMT is aimed at large corporations, as it stands, the law can be interpreted to require any partnership of any size to report if the partnership has any corporate partners. The task is made more challenging by the fact that many partnerships do not have audited financial statements.

Then there is the question of “distributive share.” The statute stipulates that “if the taxpayer is a partner in a partnership, adjusted financial statement income of the taxpayer with respect to such partnership shall be adjusted to only take into account the taxpayer’s distributive share of adjusted financial statement income of such partnership.” However, “distributive share” is a tax concept that does not neatly apply to book income, raising many unanswered questions. Initial regulatory guidance (which provided 50 pages of guidance on many issues) did not resolve these and other challenges with partnerships, such as how to deal with tiered partnerships.[18] As it stands, corporate partners may need to request from the partnership information on AFSI or the IRS could rule that partnerships are required to provide that information, potentially ensnaring thousands of partnerships in a new reporting requirement and compliance burden of unknown scale.[19]

Taxpayers are also concerned about one-time activities pushing them over the $1 billion income threshold that determines if they are subject to the book minimum tax. Such activities could include a sale of a business unit or other merger and acquisition activities. Guidance thus far has addressed how to treat certain transactions, such as spin-offs, but questions remain about the treatment of other extraordinary transactions. While the threshold is determined based on a three-year average of income, taxpayers have complained that this is “not an effective nor fair measure” due to the volatility of their income.[20] Some taxpayers have requested the option to drop one year from the three-year average or otherwise disregard extraordinary transactions.[21] These considerations are especially important because once a taxpayer is subject to the book minimum tax, the taxpayer remains subject to it forever regardless of income (but the Treasury Secretary can grant exceptions). An additional problem with the $1 billion threshold is the lack of inflation indexingInflation indexing refers to automatic cost-of-living adjustments built into tax provisions to keep pace with inflation. Absent these adjustments, income taxes are subject to “bracket creep” and stealth increases on taxpayers, while excise taxes are vulnerable to erosion as taxes expressed in marginal dollars, rather than rates, slowly lose value. , so over time more companies will be swept in (the price level has already increased about 3 percent since the passage of the tax, as measured by the Consumer Price Index).

Comment letters from taxpayers and practitioners identify numerous other specific issues with the BMT, sometimes disagreeing on how best to resolve them.[22] For instance, the American Bar Association and New York State Bar Association agree the initial guidance should change regarding basis adjustment rules to determine whether financial accounting or tax rules apply for recognition of gain or loss in some reorganization transactions, but various factions come to different conclusions on how to address it. Related to that is the issue of how far back to look to make adjustments for income and asset basis. Tax lawyers generally agree there should be a limited look-back period but do not agree on a time-specific limit. Regarding the safe harbor rule specified in the initial guidance, which allows certain companies to avoid the tax in 2023 using a simplified determination, tax lawyers generally agree with the rule but request that it be made more broadly applicable and extended permanently.

Finally, in the latest announcement on June 7, the IRS granted penalty relief for corporations that do not pay estimated tax for 2023 related to the book minimum tax, due to “challenges associated with determining whether a corporation is an Applicable Corporation and the amount of a corporation’s CAMT liability.”[23]

It is not clear when the IRS will provide additional guidance or to what degree it might address the issues raised in comment letters. In March of this year, an IRS official described the regulatory process for the BMT as “a long slog” while a Treasury official indicated plans to release “more detailed and refined proposed regulations later this year.”[24]

Buyback Tax

Compared to the book minimum tax, the tax on net share repurchases (or buybacks) is relatively straightforward. The statute calls for a 1 percent excise tax applicable to publicly traded companies on the value of their stock repurchases during the taxable year, net of new issuances of stock, for repurchases after December 31, 2022. The tax excludes stock contributed to retirement accounts, pensions, and employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs). Subsequent guidance introduced a controversial rule that greatly expands the scope of the tax to apply to share repurchases by foreign-headquartered companies with U.S. affiliates.

The statute indicates that if a U.S. company buys the stock of its public foreign affiliate, then the excise tax could apply. While such a situation is rare, guidance issued in December expanded the scope of the tax to include, in many cases, share repurchases made by foreign companies with U.S. affiliates (inbound companies).[25] The guidance accomplished the expansion by creating an overly broad funding rule. The rule provides that if the U.S. company “funds” its foreign affiliate by sending payments for nearly any reason within two years of a stock repurchase by the foreign affiliate, the tax applies to that stock repurchase. Cross-border payments that could trigger the tax include payments for common business services, such as interest payments, royalties, inventory purchases, and funding for an in-house bank.

Comment letters from foreign-headquartered companies point to the dangers of the ruling, including reciprocal actions from foreign governments that could turn around and tax U.S.-based multinational enterprises (MNEs) in the same way.[26]

Perhaps acknowledging these concerns, on June 29, the IRS issued guidance indicating taxpayers are not required to report the buyback tax on their tax return or make any payments of the tax until further guidance is issued, recommending in the meantime that taxpayers keep records for share repurchases made after December 31, 2022.[27] It is not clear when further guidance may be issued, but the general expectation is that it will likely arrive before the end of this year and will clarify the funding rule to be more in line with the statute.

Clarifying the funding rule will eliminate much of the remaining uncertainties about the tax, but it will not eliminate the tax’s distortionary effects. As many policy experts have noted, the tax is aimed at discouraging companies from distributing excess cash to shareholders in the form of buybacks, but it is not at all clear why this behavior should be punished. Companies can distribute cash to owners through dividends or buybacks, and companies have legitimate reasons for choosing one or the other.

For example, while dividends are typically used for regular distributions, buybacks provide a degree of flexibility for the company and a means to issue one-time distributions without creating shareholder expectations that they will continue.[28] No evidence exists to indicate buybacks come at the expense of investment; instead buybacks allow companies to release excess cash in an efficient manner, allowing shareholders to recycle funds into other investments.[29] The new buyback tax, once fully implemented and enforced, will interrupt and distort the efficient and beneficial process of recycling investable funds, leading to fewer buybacks along with some combination of increased dividend payouts and inefficient use of funds by companies.[30]

Green Energy Tax Credits

One of the most ambitious parts of the IRA is the expansion or creation of 22 tax credits for green energy development and use, subsidizing various technologies related to zero-carbon energy generation, electric vehicles, residential clean energy, alternative fuels, and advanced manufacturing.[31] The credits have two primary goals: increasing the development and deployment of low- or zero-emission technologies and increasing investment and growth in the U.S. economy broadly.[32]

The IRA credits can be sorted according to typical emissions sectors: utility-level electricity and power generation, transportation, commercial and residential buildings, and industrial activities.[33]

Table 1. Inflation Reduction Act Credits

| Electricity Generation Sector | Transportation Sector | Commercial and Residential Building Sector | Industrial Sector and Miscellaneous |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extension and Modification of Credit for Electricity Produced from Certain Renewable Resources (Section 45) | Incentives for Biodiesel, Renewable Diesel, and Alternative Fuels (Section 40A) | Extension, Increase, and Modifications of Nonbusiness Energy Property Credit (Section 25C) | Extension and Modification of Credit for Carbon Oxide Sequestration (Section 45Q) |

| Extension and Modification of Energy Credit (Section 48) | Extension of Second Generation Biofuel Incentives (Section 40) | Energy Efficient Commercial Buildings Deduction (Section 179D) | Cost Recovery for Qualified Facilities, Qualified Property, and Energy Storage Technology (Section 168) |

| Zero-Emission Nuclear Power Production Credit (Section 45U) | Sustainable Aviation Fuel Credit (Section 40B) | Extension, Increase, and Modification of New Energy Efficient Home Credit (Section 45L) | Advanced Manufacturing Production Credit (Section 45X) |

| Clean Electricity Production Credit (Section 45Y) | Clean Hydrogen Production Credit (Section 45V) | Residential Clean Energy Credit (Section 25D) | Extension of Advanced Energy Project Credit (Section 45C) |

| Clean Electricity Investment Credit (Section 48E) | Clean Vehicle Credit (Section 30D) | ||

| Credit for Used Clean Vehicles (Section 25E) | |||

| Qualified Commercial Clean Vehicles (Section 45W) | |||

| Alternative Fuel Refueling Property Credit (Section 30C) | |||

| Clean Fuel Production Credit (Section 45Z) |

Power Sector Credits

The five tax credits aimed at reducing emissions in the power sector reduce uncertainty in tax breaks for green energy in some ways. Provisions such as the energy production credit and energy investment credit used to be extenders requiring renewal almost every year. Now, most of the new green policies will be in place for 10 years. The longer availability stabilizes incentives for companies to make investment decisions, avoiding the uncertainty associated with the year-end push to extend expiring provisions.[34]

It is also worth clarifying that the IRA extended and expanded existing credits for clean energy investment (Section 48) and production (Section 45) until the beginning of 2025. Starting in 2025, the IRA’s new production and investment credits (Section 45Y and Section 48E, respectively) will effectively replace the pre-existing credits with an improved technology-neutral policy. The IRA also introduced a tax creditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. (Section 45U) for existing nuclear power production.

But the IRA’s new credits have come with new complexities. Many pair stability regarding incentives with complexity within the incentives themselves. For instance, the new power credits include bonus credits for paying prevailing wages (aimed at boosting unionized labor), establishing apprenticeships, meeting domestic content requirements, and locating activities in communities historically home to substantial fossil fuel industry.

The contingencies have necessitated additional guidance from the IRS. In November 2022, the IRS published guidance on the wage and apprenticeship requirements, primarily affecting the power generation sector.[35] In February 2023, the IRS published initial guidance on the energy community and low-income community bonus credits and issued new or updated guidance in April and June as well.[36] The agency published initial guidance for the domestic content bonus credits in May 2023, with particular consideration for what qualifies as domestically produced.[37]

Another issue relevant for the power sector credits (as well as for several other policies) is direct pay and transferability. Tax credits are used to offset tax liability, but some entities have no existing tax liability to offset, such as startup companies not yet profitable or nonprofit and governmental entities. To make the IRA incentives available to such entities, the IRA allows credits to be sold to other taxpayers with tax liability (transferability) or for direct payments to be made in terms of the value of the credit. This policy choice has necessitated additional guidance.[38] Transferability further blurs the line between tax credits and government spending. While it will create additional incentives for untaxed entities to invest in green energy, it could also lead to significant compliance and administrative challenges for both taxpayers and the IRS.[39]

Transportation Sector Credits

Nine credits are aimed at reducing emissions from the transportation sector. Most of the subsidies for transportation focus on reducing emissions from road travel, predominantly by subsidizing electric vehicles (EVs) (Section 30D, Section 25D, and Section 45W) and EV infrastructure (Section 30C). However, others focus on alternative fuels like biodiesel (Section 40, Section 40A, Section 40B, Section 45Z).[40] Lastly, Section 45V provides a tax credit for clean hydrogen technology, which has the potential for numerous applications across sectors, but most prominently transportation.[41]

The several tax credits related to EVs have been at the center of compliance challenges and controversies. For one, the eligibility for EV credits is partly contingent on the production location of critical minerals and battery components, not to mention production of the vehicles themselves.[42] The domestic content requirements led to significant tumult internationally, particularly from the European Union, South Korea, and Japan.[43]

Over the past year, the administration has slowly tweaked the credits to make them more available for foreign-produced cars. In December 2022, guidance made foreign-made vehicles eligible for the commercial vehicle credit, as long as the vehicles were leased. In late March and early April of 2023, deals with South Korea and Japan essentially satisfied the domestic content requirement for cars they produced.[44] The U.S. and EU may yet reach an agreement regarding eligibility of EU-produced cars, but negotiations are at an impasse.[45]

The long series of IRS guidance illustrates the complexities of the EV credits. In December 2022, the IRS issued the first set of notices and an FAQ page, followed by another update in February.[46] The IRS also released guidance for commercial clean energy vehicles at the end of December 2022, later updating the guidelines in February 2023.[47] While these publications have helped taxpayers navigate these complex credits, future policy changes thanks to negotiation with European countries may necessitate another round of guidance.

Commercial and Residential Buildings Credits

Four provisions are targeted at emissions produced within homes and businesses.

Two credits are focused on households. The nonbusiness energy property credit (Section 25D) covers 30 percent of the installation of residential-level energy property, such as solar panels, geothermal heat pumps, and small wind turbines.[48] The energy efficiency improvements credit (Section 25C) covers 30 percent of costs for various home construction elements and appliances. Previously, taxpayers faced a $500 lifetime limit, but the IRA raised the maximum value to $1,200 per year and removed lifetime limits.[49] The IRA also tweaked qualifying expenditures for each credit.[50]

Meanwhile, the other tax provisions related to building sector emissions are more focused on businesses. The credit for the construction of new housing units that meet certain energy efficiency requirements (Section 45L) is allocated to construction contractors.[51] The Energy Efficient Commercial Buildings Deduction (Section 179D) provides an extra tax deductionA tax deduction is a provision that reduces taxable income. A standard deduction is a single deduction at a fixed amount. Itemized deductions are popular among higher-income taxpayers who often have significant deductible expenses, such as state and local taxes paid, mortgage interest, and charitable contributions. for energy efficiency improvements in commercial buildings, which helps compensate for overall poor tax treatment of energy efficiency improvements and structures investment in some ways.[52] But like many other policies in the IRA, the incentive features substantial bonuses for prevailing wages.[53]

Industrial and Miscellaneous Credits

The other major category of CO2 emissions is industrial emissions, where various industrial processes, such as cement production, release CO2 and other greenhouse gases as a byproduct. Rather than focus on emissions, the tax credits directly applied to industrial production are more concerned with onshoring industrial production of various green energy components.

The IRA also expanded the existing tax credit for carbon sequestration, both the values provided per ton of CO2 captured for different activities and the eligible facilities.[54] Like many other credits, the additional value of the credit is contingent on prevailing wage requirements. This detail has led to some uncertainty, as carbon sequestration technology is often attached to an existing facility that may not have been constructed with the prevailing wage requirements of the credit.[55]

The IRA’s credit for qualified advanced energy projects (Section 48C) has several notable features. It provides a base credit of 6 percent of costs for clean energy project manufacturing and recycling, emissions reduction projects in the industrial production sector, and the production of specified critical minerals. The credit can then be boosted to 30 percent by meeting several conditions such as prevailing wage and domestic content requirements.[56]

Section 48C is also notable for how it blurs the line between tax credit and grant program, as it requires projects to go through an application process.[57] Unlike other credits, which are largely uncapped, the advanced energy property credit is limited to $10 billion, to be allocated by the IRS. Furthermore, the credit can only be claimed once, and no less than $4 billion of the credit must be allocated to existing energy communities, per initial and subsequent guidance issued in February and May.[58]

The advanced manufacturing production credit (Section 45X) is targeted at critical mineral production, as well as the production of other green energy products and components. The credit is worth 10 percent of the cost of production of a long series of minerals.[59] Notably, it is not to be confused with the Advanced Manufacturing Investment Credit introduced in the CHIPS Act of 2022.[60] Relative to Section 48C, Section 45X is a more conventional tax credit.

Fiscal Impact

The fiscal impact of the IRA green energy credits looks like it will be much larger than originally anticipated. When the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) reassessed the revenue cost in May 2023, they found a rough doubling since the law’s enactment: from 2023 to 2031, they found a $536 billion cost compared to the original $271 billion cost.[61] In particular, the Advanced Manufacturing Production Credit, the modified energy credit, and the EV credits saw large increases in estimated costs, with all of them more than quadrupling. JCT attributes the growth to several factors including Treasury’s expansive guidance as well as increases in anticipated production capacity for batteries and renewable energy. JCT also provided estimates over a longer budget window, finding the credits cost $663 billion over the period 2023 to 2033.

Table 2. IRA Green Energy Credit Fiscal Costs as Estimated by the Joint Committee on Taxation, 2023 to 2031

| JCT Score (August 2022), 2023-2031 | Preliminary Revised JCT Score (May 2023), 2023-2031 | Net Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Credit for Electricity from Renewables (Section 45) | $51.10 | $63.60 | $12.50 |

| Modification of Energy Credit (Section 48) | $14 | $60.10 | $46.10 |

| Clean Vehicle Credits | $11.10 | $69.40 | $58.30 |

| Advanced Manufacturing Production Credit (Section 45X) | $30.60 | $132.50 | $101.90 |

| Carbon Sequestration Credit (Section 45Q) | $3.20 | $17.40 | $14.20 |

| Clean Fuel Production Credit (Section 45Z) | $2.90 | $7.40 | $4.50 |

| Clean Electricity Investment Credit (48E) | $50.90 | $71.70 | $20.80 |

| Other | $107.20 | $114.30 | $7.10 |

| Total | $271.00 | $536.40 | $265.40 |

JCT’s analysis has not factored in recent climate efforts by government agencies that could push cost estimates higher.[62] For example, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has recently proposed rules that mandate stricter emissions standards for new vehicles starting in 2027, effectively requiring a major shift to EVs.[63] The EPA estimates the new regulations could add as much as $210 billion in tax revenue losses between 2027 and 2032: $136 billion from EV credits and $74 billion from the battery production credit.[64]

Analyses by several other organizations also point to escalating fiscal costs. For example, the Penn-Wharton Budget Model estimates the combined energy and climate provisions in the IRA will cost about $1 trillion over the next decade, while Goldman Sachs puts the cost at about $1.2 trillion.[65] A study by scholars at the Brookings Institution finds the fiscal cost through 2031 could range from $244 billion to $1.1 trillion depending on assumptions about eligibility and supply constraints.[66]

Economic Impact

The rising fiscal costs of the IRA credits reflect increasing taxpayer interest, uptake, and potentially larger economic effects than originally expected. Fundamentally, tax credits for specific types of investment should have two effects. First, the overall average tax burden on investment should fall, incentivizing additional investment. Second, the relative value of different investments should change, causing investment to shift from unsubsidized sectors to newly subsidized sectors.

Since the passage of the IRA, we have seen substantial new investments in subsidized sectors and industries, but no clear sign of a broad increase in investment economy-wide.[67] More data will be required, but even with years of data, it will be difficult to isolate the impact of the IRA’s tax changes, particularly on overall investment, due to confounding policy developments and economic factors.

For example, as mentioned, stricter emissions standards for new cars, which have been pursued by the Biden administration since early 2021, have also encouraged investment in EVs. The CHIPS Act, enacted in 2022, provides significant investment subsidies for certain industries. On the other hand, the Federal Reserve has substantially hiked interest rates over the last year and a half while taxes on business investment have increased (e.g., due to the phaseout of bonus depreciation and the requirement to amortize research and development [R&D] expenses as specified in the TCJA).

The trend towards green energy investment and adoption of cleaner technologies predates the IRA. A decades-long series of technological improvements have steadily improved the quality and lowered prices of key technologies such as batteries and solar panels, making widescale adoption and deployment much more feasible even without additional subsidies. As such, it is unclear to what degree the IRA credits have added to the trend by boosting marginal incentives or if they have merely subsidized technologies that would have been developed anyway.

Furthermore, investment in itself is not a policy success. The goal of investment is to increase productivity, which should then lead to increases in wages and living standards. Usually, we can be confident that each part of this chain will hold up. In the IRA’s case, though, we have good reasons to be concerned. Targeting all of the tax benefits to a few industries could result in a glut of investment that ultimately proves to be unproductive. On the other hand, the tax credits could accelerate technological development thanks to “learning by doing”; while, initially, some investment may not be particularly productive, increased activity in the sector could spur productivity improvements.[68]

Drug Pricing

The IRA imposed a new policy, the “Drug Price Negotiation Program,” to allow the government to determine a “maximum fair price” companies can charge for certain prescription drugs within Medicare. If pharmaceutical companies do not comply with government-set prices, they will face steep excise taxes ranging from 186 percent to 300 percent, 567 percent, or 1,900 percent on their drug sales, depending on the amount of time out of compliance.

Official estimates of the new law indicate an expectation that all manufacturers would comply with the government-set prices rather than pay the excise tax penalties, so that the tax itself does not raise any revenue. Manufacturers may also respond in other, unintended ways, including pulling a drug out of the U.S. market, refocusing development on drugs that are less likely to be a top Medicare drug, or other operational adjustments to reduce or avoid being caught up in the drug pricing program.[69]

Each year, the government will select from a list of 50 drugs with the most spending in Medicare Part B and 50 in Medicare Part D. Eligible drugs include single-source small molecule drugs that have been on the market for seven years and biologics that have been on the market for 11 years.

In 2023, the government can select from the list the first 10 drugs to face price restrictions, which will kick in starting in 2026. In 2025 and 2026, the government can select another 15 drugs each year, after which it can select 20 drugs per year. While price controls only apply to Medicare Part D in 2026 and 2027, afterward they will apply to Part B as well.

Forcibly lowering prices will reduce prescription drug spending, saving the government money by lowering expenditures within Medicare. But it will also reduce investments in biopharmaceutical R&D that produce new drugs and find new applications for existing drugs. For example, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that earlier versions of the drug pricing legislation would cause a 5 percent reduction in innovation, meaning 8 to 15 fewer drugs coming to market over the next decade.[70] Outside estimates put the number much higher, suggesting CBO’s estimate is a lower bound for potential innovation losses.[71]

Preliminary anecdotes indicate the predicted loss in innovation is already taking place, as several drug companies have announced curtailment of various drug development projects, pointing to the new law.[72]

The Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services (CMS) issued its guidance on March 15, 2023, less than six months before the deadline for drug manufacturers to sign agreements with CMS, with comments due by June 20, 2023.[73]

According to the comment solicitation letter, “In order to facilitate the timely implementation of the Negotiation Program, CMS is issuing guidance on section 30 of this memorandum as final, without a comment solicitation,” save for a small exception within that section. Section 30 is related to how CMS will identify, rank, and select the negotiation-eligible drugs for 2026 price restrictions, and not allowing public comment on that fundamental component of the program is highly questionable.

The tight timeline, issuing a major section of guidance as final, and the effects the drug pricing policy will ultimately have on innovation, drug development, and patient access, all illustrate the misguided approach the IRA took to reduce Medicare spending. While Medicare reform should be on the table as lawmakers address debt, deficits, and inflation, lawmakers should explore other policy options.[74]

IRS Funding

The IRA included a substantial funding increase for the IRS to use from Fiscal Year 2022 to Fiscal Year 2031. The funding can be broken into four categories: enforcement, operations support, business system modernization, and taxpayer services.

Table 3. IRS Funding Increases under the IRA

| Additional Funding (FY 2022-2031) | Percentage Increase over Baseline Funding | |

|---|---|---|

| Enforcement | +$45.64 billion | 69% |

| Operations Support | +$25.33 billion | 53% |

| Business System Modernization | +$4.75 billion | 153% |

| Taxpayer Services | +$3.18 billion | 9% |

| Total | +$78.90 billion | 2% |

The spending can also be divided into different categories based on policy goal. In the IRS’s Strategic Operating Plan, released this April, the agency presented five objectives for the funding package, as well as a separate item for implementing the IRA’s green energy credits. Each objective involves funding from multiple spending categories. For instance, the goal to “deliver cutting-edge technology, data, and analytics” includes funds from both the Business System Modernization and Operations Support account.[75]

Table 4. IRS Funding Increases by Operating Plan Objective

| Strategic Operating Plan Objective | Total Proposed Investment, FY2022-2031, Appropriations Account |

|---|---|

| Dramatically improve services to help taxpayers meet their obligations and receive the tax incentives for which they are eligible | $4.3 billion |

| Quickly resolve taxpayer issues when they arise | $3.2 billion |

| Focus expanded enforcement on taxpayers with complex tax filings and high-dollar noncompliance to address the tax gap | $47.4 billion |

| Deliver cutting-edge technology, data, and analytics to operate more effectively | $12.4 billion |

| Attract, retain, and empower a highly skilled, diverse workforce and develop a culture that is better equipped to deliver results | $8.2 billion |

| Energy Security | $3.9 billion |

| Total | $79.4 billion |

Ultimately, the IRS funding package has two core goals, with some of the listed objectives serving both.[76]

The first goal is improving IRS customer service. IRS customer service was already poor before the COVID-19 pandemic. It further deteriorated as lawmakers saddled the agency with administrating several massive economic relief programs during the pandemic.

The second goal is raising revenue by improving enforcement, thus reducing tax noncompliance. Reducing noncompliance would narrow the tax gapThe tax gap is the difference between taxes legally owed and taxes collected. The gross tax gap in the U.S. accounts for at least 1 billion in lost revenue each year, according to the latest estimate by the IRS (2011 to 2013), suggesting a voluntary taxpayer compliance rate of 83.6 percent. The net tax gap is calculated by subtracting late tax collections from the gross tax gap: from 2011 to 2013, the average net gap was around 1 billion. (the difference between taxes legally owed and taxes collected) and help fund the green energy subsidies included in the IRA. Funding for workforce development and technological upgrades could help serve both core goals.[77]

Implementation so Far: Taxpayer Services and Administrative Challenges

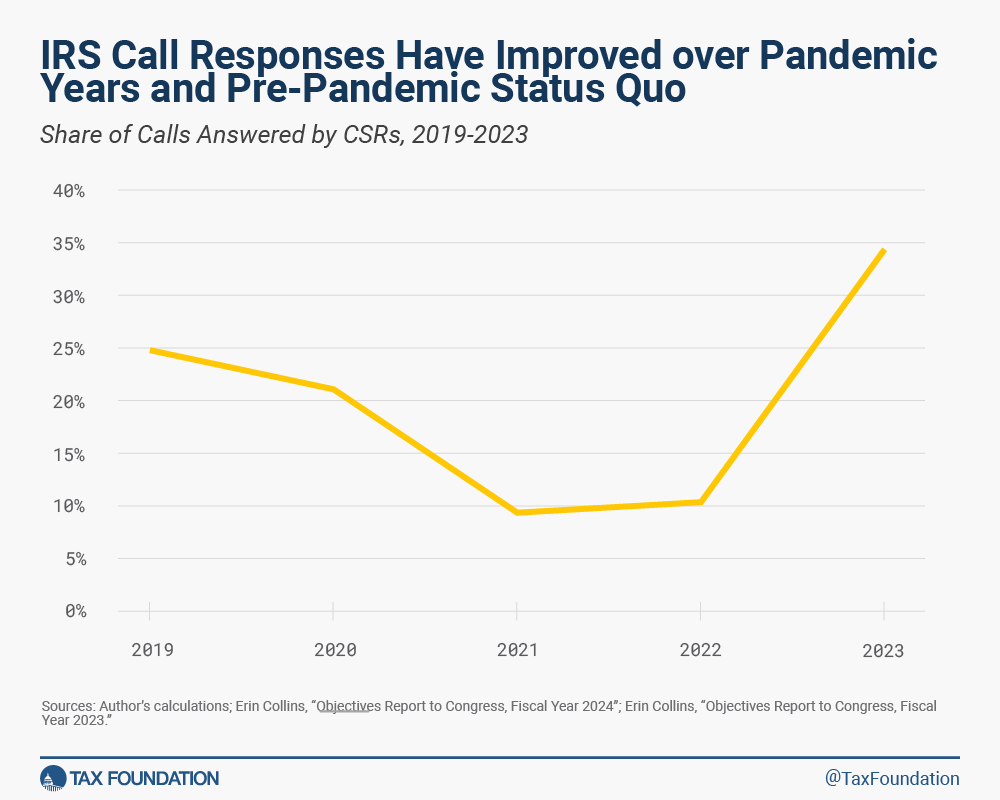

Taxpayer service has substantially improved in the 2023 filing season. One of the most salient examples of service woes was unresponsive telephone assistance. Customer service response rates sunk to roughly 10 percent in the two tax seasons preceding the IRA’s passage. Responsiveness improved during the 2023 tax season, after the agency used new funds to hire 5,000 new customer service employees.

During the 2023 tax season, IRS customer service agents answered over 34 percent of incoming calls compared to roughly 10 percent of calls in 2021 and 2022 and 25 percent of calls in 2019, the last pre-pandemic tax season.

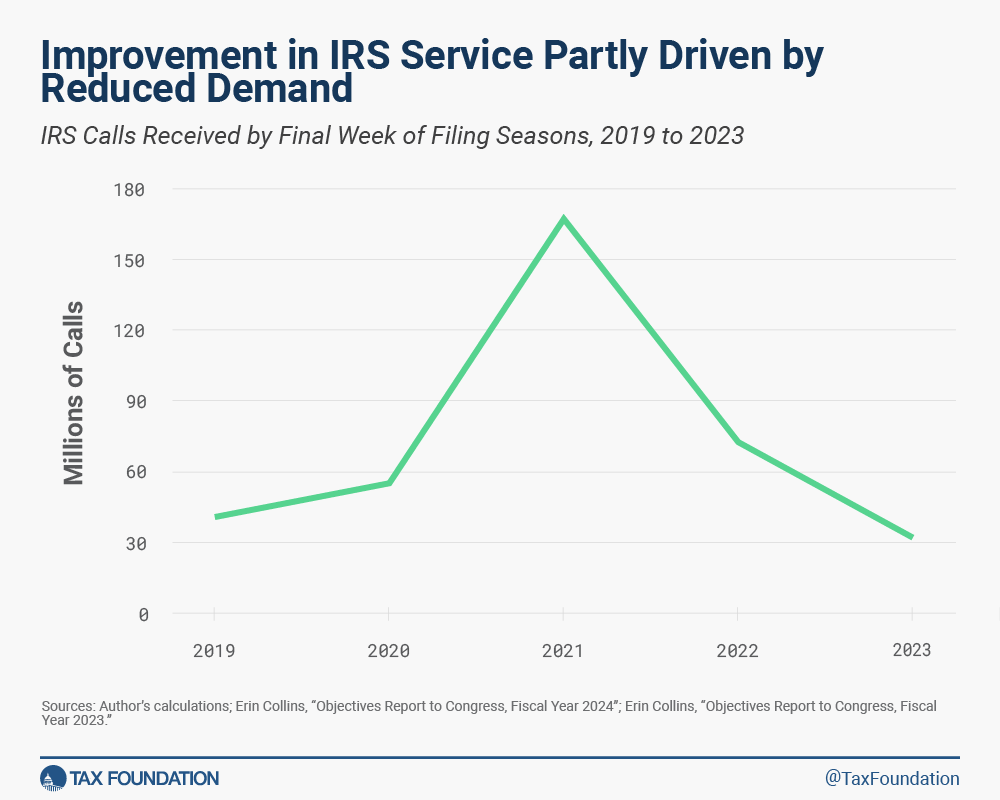

It is worth noting that some customer service improvements have been due to reduced demand, not increased capacity. In 2022, pandemic-era relief programs, most notably the expanded Child Tax Credit, expired, meaning fewer questions and reduced demand for IRS service. Calls to the IRS fell by more than 50 percent, from almost 73 million in the 2022 tax season to just 32 million in the 2023 tax season.

Another indicator of the IRS’s service deficiencies is the backlog of paper returns. National Taxpayer Advocate Erin Collins has described paper tax returns, still submitted by millions of taxpayers, as the IRS’s kryptonite.[78] A 2022 story from The Washington Post vividly documented the laborious and comically outdated methods the IRS uses to process paper tax returns.[79] At the end of the 2022 tax filing season, the IRS was still processing some paper returns filed during the 2021 calendar year and had a total of 13.3 million paper returns and 29.1 million items of correspondence awaiting manual processing.[80]

The IRS has substantially cleared up their backlog since the IRA’s passage. By the end of the 2023 filing season, the IRS had completely cleared its 2022 backlog, and had just 2.6 million remaining paper returns awaiting processing. Additionally, it had a total inventory of 16.9 million items of correspondence awaiting manual processing, over a 40 percent drop. This progress is mainly due to the additional workers available to process returns, although some technology improvements have helped as well.[81]

Most metrics show that the IRS has delivered on improved service, even if helped by a post-pandemic decline in demand, but some concerning signs remain.

The first is a misallocation of resources aimed at juicing service specific metrics. As noted in the National Taxpayer Advocate’s midyear report, the increased focus on telephone responsiveness has led to a buildup of amended returns awaiting processing.[82]

The second and more concerning factor is the rate at which the IRS has burned through the new service funding. According to the Strategic Operating Plan, the agency will exhaust its new service funding within four years if it maintains current level of service.[83]

The IRS’s Strategic Operating Plan also provides a clear illustration of the administrative challenges the IRA credits have created. In the April report, the IRS requested an additional $3.9 billion in funding to further implement the IRA’s green energy credits, as the credits’ administrative cost is eating into the ability to fund other objectives, such as increased enforcement and improved customer service.[84]

Relative to taxpayer service, enforcement effectiveness is more difficult to measure. To start, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) did not predict that the additional enforcement funding would raise additional revenue in the next couple of years due to the time required to recruit and train new employees and to upgrade technology.[85] The CBO estimated that the IRS enforcement provisions of the IRA would raise just $2 billion in revenue in 2023 and $5.1 billion in 2024, which are marginal changes in the context of a tax gap often estimated to be near or above $500 billion per year.[86] However, in later years, the figures are more impressive: CBO estimates that the enhanced IRS enforcement activities would raise an additional $35 billion in revenue in 2030 alone.[87]

The IRS’s Strategic Operating Plan highlights the development time needed for its enforcement initiatives to take effect. For almost every initiative under the objective “Focus Enforcement on Taxpayers with Complex Tax Filings and High-Dollar Noncompliance to Address the Tax Gap,” the fiscal year 2023 goal is to hire and onboard new specialists and begin the process of raising auditA tax audit is when the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) conducts a formal investigation of financial information to verify an individual or corporation has accurately reported and paid their taxes. Selection can be at random, or due to unusual deductions or income reported on a tax return. rates, particularly for large corporations, partnerships, and high-wealth individuals, with refining of operational strategies coming in future years.[88]

Next year, the IRS will release data regarding audits in Fiscal Year 2023, which may provide some insight into how audit rates have increased at the agency and the extent to which “recommended additional tax”, i.e., increases in taxes owed resulting from the audits, changed in the first tax season of expanded IRS funding.[89] Given the time it will take to ramp up enforcement efforts, we would still not expect a substantial bump in additional revenue until a few years down the line.

The IRS publishes tax gap estimates with a long lag. In 2022, it published an analysis of the tax gap for 2014 through 2016 with estimates for the gap in 2017 through 2019. Given that we do not have estimates of the tax gap for current years, it may be some time before we can evaluate the effects of enforcement changes on the tax gap with any degree of certainty.[90]

Further complicating the implementation of the IRS’s enforcement agenda, the recent debt ceiling deal repurposed around $20 billion of the $80 billion funding increase the IRA granted the IRS, while outright cutting $1.4 billion.[91] It appears taxpayer service funding will be spared from the reduction, meaning that the planned enforcement expansions may be curtailed. For now, the IRS has said it will continue with its investment plans, but unless the funds are restored, the plans may need to be consolidated.[92] The IRS has not specified which objectives or initiatives may be at risk due to the approximate 25 percent reduction of its funding.

The jury is still out on the impact of the IRS funding increase in its totality. The most informative data available so far show that the IRS has made progress in improving customer service, but that they may need additional funds to maintain the improved level of service going forward.

Conclusion

Enacted one year ago and now in various stages of implementation, the IRA represents an ambitious effort to achieve multiple, competing goals with varying levels of success. The goal of deficit reduction, and therefore inflation reduction, is most clearly off course. The best evidence indicates the law is increasing deficits, potentially by hundreds of billions of dollars, due to explosive growth in cost estimates for the green energy credits.[93] Additionally, two of the law’s major revenue raisers, the book minimum tax (BMT) and stock buyback tax, have been put on hold until further guidance is issued.

Some of the outstanding issues with the BMT are so daunting it is currently unclear the tax can be salvaged as a viable revenue raiser without greatly increasing compliance costs and taxpayer uncertainty. To the extent the BMT is implemented, there is no reason to think it would ensure a minimum level of taxation since it allows tax credits and other tax preferences. Instead, whatever revenue it raises would arbitrarily penalize certain companies, such as those with past losses and foreign earnings.[94] Accountants have warned the BMT could reduce the quality of financial information. As these and other problems become more apparent, the case for repealing the BMT will grow. Congress should cut to the chase and relieve taxpayers and the IRS from the burden of the BMT.

In contrast, the IRA’s other major goal of addressing climate change by massively subsidizing green energy appears to be successful, at least as indicated by the exploding cost of associated tax credits. While many factors have contributed to this, including other government policies pushing in the direction of a greener economy, it cannot be denied that the credits have spurred a gold rush towards EVs and other green technologies. But, as the budgetary cost of the subsidies has grown to more than double the original estimates, larger budgetary disfunction and escalating deficits have followed, leading Fitch Ratings to downgrade U.S. debt.[95] For this reason, Congress should consider controlling the cost, either by capping the credits or repealing them. Lawmakers have at their disposal more fiscally responsible policies to address concerns about climate change in a broad, market-based way, such as a carbon taxA carbon tax is levied on the carbon content of fossil fuels. The term can also refer to taxing other types of greenhouse gas emissions, such as methane. A carbon tax puts a price on those emissions to encourage consumers, businesses, and governments to produce less of them. .

Reflecting the law’s growing fiscal cost, the IRA is probably stimulative to the economy on net, at least in the short-term, until the BMT and buyback tax are fully implemented, and before drug price controls present a substantial drag on drug innovation. By most accounts, the economy in 2022 was not in need of stimulus, but rather was extremely overheated, leading the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates at the fastest pace since the 1980s. This is yet another reason to trim the IRA’s stimulative effect, particularly the green energy credits, so that it does not further add to inflation.

Ultimately, the more lawmakers simplify the tax code in fiscally responsible ways, as recommended here, the more they will reduce inflationary pressures and improve tax administration, the taxpayer experience, and compliance. While early signs indicate the IRA’s boost to the IRS budget has improved customer service, which is needed, the IRS cannot reasonably be expected to implement and properly enforce a new complicated tax on book income and 22 complicated tax credits on top of an already overly complicated tax code, even with an expanded budget.[96] The path to improving the budget process and budgetary outcomes is through simplification.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

SubscribeReferences

[1] Alex Durante et al., “Details and Analysis of the Inflation Reduction Act Tax Provisions,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 12, 2022, https://taxfoundation.org/inflation-reduction-act/.

[2] See Appendix for summary of IRS and Treasury Department guidance to date for the book minimum tax, buyback tax, and green energy tax credits.

[3] The major provisions covered in this analysis are the book minimum tax, the buyback tax, the excise tax on drug companies, the green energy credits, and the IRS funding boost. The IRA includes other policies not covered here, including an extension of the Premium Tax Credits that were expanded in the American Rescue Plan and an extension of loss limitations for pass-through businesses. See Alex Durante et al., “Details and Analysis of the Inflation Reduction Act Tax Provisions,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 12, 2022, https://taxfoundation.org/inflation-reduction-act/.

[4] IRS, “Treasury, IRS Issue Interim Guidance on New Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax,” Dec. 27, 2022, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/treasury-irs-issue-interim-guidance-on-new-corporate-alternative-minimum-tax; IRS, “Initial Guidance Regarding the Application of the Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax under Sections 55, 56A, and 59 of the Internal Revenue Code,” Notice 2023-7, Dec. 27, 2022, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-23-07.pdf; Monisha C. Santamaria, Sarah Staudenraus, Nick Tricarichi, Daniel Winnick, and Jessica Teng, “CAMTyland Adventures, Part 1: How to Play the Game – Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax Basics,” Tax Notes, Jul. 24, 2023, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-federal/corporate-alternative-minimum-tax/camtyland-adventures-part-i-how-play-game-corporate-alternative-minimum-tax-basics/2023/07/24/7gzqf#7gzqf-0000021; Monisha C. Santamaria, Sarah Staudenraus, Nick Tricarichi, Daniel Winnick, and Jessica Teng, “CAMTyland Adventures, Part II: ‘Right-Sizing’ in the Licorice Lagoon,” Tax Notes, Jul. 31, 2023, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-federal/corporate-alternative-minimum-tax/camtyland-adventures-part-ii-right-sizing-licorice-lagoon/2023/07/31/7h0nq#7h0nq-0000073.

[5] See, for instance: Michelle Hanlon and Jeff Hoopes, “Open Letter of Concern from 264 Accounting Academics Regarding Including Financial Accounting Income in the Tax Base,” Nov. 5, 2021, https://tax.unc.edu/index.php/news-media/open-letter-of-concern-from-264-accounting-academics-regarding-including-financial-accounting-income-in-the-tax-base/; Michelle Hanlon and Terry Shevlin, “Book-Tax Conformity for Corporate Income: An Introduction to the Issues,” Tax Policy and the Economy 19 (September 2005), https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/tpe.19.20061897; Garrett Watson and William McBride, “Evaluating Proposals to Increase the Corporate Tax Rate and Levy a Minimum Tax on Corporate Book Income,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 24, 2021, https://taxfoundation.org/biden-corporate-income-tax-rate/; Alex Muresianu and Erica York, “It Would Be a Mistake to Resurrect the Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 4, 2022, https://taxfoundation.org/corporate-alternative-minimum-tax/; Cody Kallen, William McBride, and Garrett Watson, “Minimum Book Tax: Flawed Revenue Source, Penalizes Pro-Growth Cost RecoveryCost recovery is the ability of businesses to recover (deduct) the costs of their investments. It plays an important role in defining a business’ tax base and can impact investment decisions. When businesses cannot fully deduct capital expenditures, they spend less on capital, which reduces worker’s productivity and wages. ,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 5, 2022, https://taxfoundation.org/inflation-reduction-act-accelerated-depreciation/; Cody Kallen and Garrett Watson, “Who Gets Hit by the Inflation Reduction Act Book Minimum Tax,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 12, 2022, https://taxfoundation.org/book-minimum-tax-analysis/; Kyle Pomerleau, “The Minimum Book Tax Is Not a ‘Second Best’ Reform,” American Enterprise Institute, Dec. 24, 2021, https://www.aei.org/op-eds/the-minimum-book-tax-is-not-a-second-best-reform.

[6] Brian Faler, “’Do Your Best’: Businesses Confront Dems’ New Minimum Tax Without Guidance from Treasury,” Politico, Nov. 17, 2022, https://subscriber.politicopro.com/article/2022/11/do-your-best-businesses-confront-dems-new-minimum-tax-without-guidance-from-treasury-00067885; Chandra Wallace, “IRS Counsels Patience on Corporate AMT Guidance,” Tax Notes, Mar. 2, 2023, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-today-federal/corporate-alternative-minimum-tax/irs-counsels-patience-corporate-amt-guidance/2023/03/02/7g07k.

[7] Tax Policy Center, “Raising Revenue from Corporations,” May 16, 2023, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/event/raising-revenue-corporations; Chandra Wallace, “Broad Exclusions from Corporate AMT Sought by CEO Group,” Tax Notes, Mar. 27, 2023, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-today-federal/corporate-alternative-minimum-tax/broad-exclusions-corporate-amt-sought-ceo-group/2023/03/27/7g8c8; Business Roundtable, “Business Roundtable Comments in Response to Notice 2023-7, Initial Guidance Regarding the Application of the Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax under Sections 55, 56A and 59 of the Internal Revenue Code,” Mar. 22, 2023, https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-comments-in-response-to-notice-2023-7-initial-guidance-regarding-the-application-of-the-corporate-alternative-minimum-tax-under-sections-55-56a-and-59-of-the-internal-revenue-code; Alliance for Competitive Taxation, “Comments on Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax Notice 2023-07,” Mar. 20, 2023, https://actontaxreform.com/media/uajlaiys/act-comments-on-camt-guidance-notice-2023-7-_20230320.pdf; U.S. Chamber of Commerce, “Preliminary Comments on Corporate AMT Implementation,” Mar. 23, 2023, https://www.uschamber.com/taxes/preliminary-comments-on-corporate-amt-implementation; Tim Shaw, “CPAs Comment on Interim Corporate AMT Guidance,” Thomson Reuters, April 18, 2023, https://tax.thomsonreuters.com/news/cpas-comment-on-interim-corporate-amt-guidance/; AICPA, “Comments on Notice 2023-7,” Mar. 27, 2023, https://us.aicpa.org/content/dam/aicpa/advocacy/tax/downloadabledocuments/56175896-aicpa-comment-letter-corporate-alternative-minimum-tax-notice-2023-7.pdf.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Dhammika Dharmapala, “The Tax Elasticity of Financial Statement Income: Implications for Current Reform Proposals,” National Tax Journal 73:4 (December 2020), https://www.ntanet.org/NTJ/73/4/ntj-v73n04p1047-1064-Tax-Elasticity-of-Financial-Statement-Income.html.

[10] Michelle Hanlon and Jeff Hoopes, “Open Letter of Concern from 264 Accounting Academics Regarding Including Financial Accounting Income in the Tax Base” Nov. 5, 2021, https://tax.unc.edu/index.php/news-media/open-letter-of-concern-from-264-accounting-academics-regarding-including-financial-accounting-income-in-the-tax-base/; Michelle Hanlon and Terry Shevlin, “Book-Tax Conformity for Corporate Income: An Introduction to the Issues,” Tax Policy and the Economy 19 (September 2005), https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/tpe.19.20061897; Garrett Watson and William McBride, “Evaluating Proposals to Increase the Corporate Tax Rate and Levy a Minimum Tax on Corporate Book Income,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 24, 2021, https://taxfoundation.org/biden-corporate-income-tax-rate/.

[11] KPMG, “KPMG Report: Draft Forms Provide Insight Into Compliance Burden Imposed by New CAMT,” Aug. 3, 2023, https://kpmg.com/us/en/home/insights/2023/08/tnf-kpmg-report-draft-forms-provide-insight-into-compliance-burden-imposed-by-new-camt.html.

[12] Monisha C. Santamaria, Sarah Staudenraus, Nick Tricarichi, Daniel Winnick, and Jessica Teng, “CAMTyland Adventures, Part I: How to Play the Game – Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax Basics,” Tax Notes, Jul. 24, 2023, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-federal/corporate-alternative-minimum-tax/camtyland-adventures-part-i-how-play-game-corporate-alternative-minimum-tax-basics/2023/07/24/7gzqf#7gzqf-0000021; Tim Shaw, “CPAs Comment on Interim Corporate AMT Guidance,” Thomson Reuters, Apr. 18, 2023, https://tax.thomsonreuters.com/news/cpas-comment-on-interim-corporate-amt-guidance/; AICPA, “Comments on Notice 2023-7,” Mar. 27, 2023, https://us.aicpa.org/content/dam/aicpa/advocacy/tax/downloadabledocuments/56175896-aicpa-comment-letter-corporate-alternative-minimum-tax-notice-2023-7.pdf; Tax Policy Center, “Raising Revenue from Corporations,” May 16, 2023, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/event/raising-revenue-corporations.

[13] Monisha C. Santamaria, Sarah Staudenraus, Nick Tricarichi, Daniel Winnick, and Jessica Teng, “CAMTyland Adventures, Part II: ‘Right-Sizing’ in the Licorice Lagoon,” Tax Notes, Jul. 31, 2023, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-federal/corporate-alternative-minimum-tax/camtyland-adventures-part-ii-right-sizing-licorice-lagoon/2023/07/31/7h0nq#7h0nq-0000073.

[14] Michelle Hanlon and Terry Shevlin, “Book-Tax Conformity for Corporate Income: An Introduction to the Issues,” Tax Policy and the Economy 19 (September 2005), https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/tpe.19.20061897; Tax Policy Center, “Raising Revenue from Corporations,” May 16, 2023, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/event/raising-revenue-corporations.

[15] Chandra Wallace, “Broad Exclusions from Corporate AMT Sought by CEO Group,” Tax Notes, Mar. 27, 2023, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-today-federal/corporate-alternative-minimum-tax/broad-exclusions-corporate-amt-sought-ceo-group/2023/03/27/7g8c8; Andrew Velarde, “Business Groups Request Corporate AMT CFC Double-Counting Relief,” Tax Notes, Mar. 27, 2023, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-today-federal/corporate-alternative-minimum-tax/business-groups-request-corporate-amt-cfc-double-counting-relief/2023/03/27/7g8b0; Business Roundtable, “Business Roundtable Comments in Response to Notice 2023-7, Initial Guidance Regarding the Application of the Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax under Sections 55, 56A and 59 of the Internal Revenue Code“, Mar. 22, 2023, https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-comments-in-response-to-notice-2023-7-initial-guidance-regarding-the-application-of-the-corporate-alternative-minimum-tax-under-sections-55-56a-and-59-of-the-internal-revenue-code; Alliance for Competitive Taxation, “Comments on Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax Notice 2023-07,” Mar. 20, 2023, https://actontaxreform.com/media/uajlaiys/act-comments-on-camt-guidance-notice-2023-7-_20230320.pdf; U.S. Chamber of Commerce, “Preliminary Comments on Corporate AMT Implementation,” Mar. 23, 2023, https://www.uschamber.com/taxes/preliminary-comments-on-corporate-amt-implementation.

[16] U.S. Department of the Treasury, “Treasury Releases Information on Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax,” Feb. 17, 2023, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1284; IRS, “Interim Guidance Regarding Certain Insurance Related Issues for the Determination of Adjusted Financial Statement Income under Section 56A of the Internal Revenue Code,” Notice 2023-20, Feb. 17, 2023, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-23-20.pdf.

[17] Erin Slowey, “Partnerships Struggle With Impact of US Corporate Minimum Tax,” Bloomberg Tax, Oct. 4, 2022, https://news.bloombergtax.com/daily-tax-report/partnerships-struggle-with-impact-of-us-corporate-minimum-tax.

[18] Alliance for Competitive Taxation, “Comments on Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax Notice 2023-07,” Mar. 20, 2023, https://actontaxreform.com/media/uajlaiys/act-comments-on-camt-guidance-notice-2023-7-_20230320.pdf; Tim Shaw, “CPAs Comment on Interim Corporate AMT Guidance,” Thomson Reuters, Apr. 18, 2023, https://tax.thomsonreuters.com/news/cpas-comment-on-interim-corporate-amt-guidance/; AICPA, “Comments on Notice 2023-7,” Mar. 27, 2023, https://us.aicpa.org/content/dam/aicpa/advocacy/tax/downloadabledocuments/56175896-aicpa-comment-letter-corporate-alternative-minimum-tax-notice-2023-7.pdf.

[19] Any new reporting requirements would be on top of burdensome new rules that went into force last year requiring partnerships to report more information on foreign income. See, Michael Rapoport, “IRS’s Partnership Foreign Income Forms Draw Ire of Preparers,” Bloomberg Tax, Feb. 9, 2022, https://news.bloombergtax.com/daily-tax-report-international/irss-partnership-foreign-income-forms-draw-ire-of-preparers.

[20] Jennifer Williams-Alvarez, “New Corporate Minimum Tax Could Ensnare Some Firms Over One-Time Moves,” The Wall Street Journal, Mar. 30, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/new-corporate-minimum-tax-could-ensnare-some-firms-over-one-time-moves-260f74df.

[21] Chandra Wallace, “Broad Exclusions from Corporate AMT Sought by CEO Group,” Tax Notes, Mar. 27, 2023, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-today-federal/corporate-alternative-minimum-tax/broad-exclusions-corporate-amt-sought-ceo-group/2023/03/27/7g8c8; Business Roundtable, “Business Roundtable Comments in Response to Notice 2023-7, Initial Guidance Regarding the Application of the Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax under Sections 55, 56A and 59 of the Internal Revenue Code,” Mar. 22, 2023, https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-comments-in-response-to-notice-2023-7-initial-guidance-regarding-the-application-of-the-corporate-alternative-minimum-tax-under-sections-55-56a-and-59-of-the-internal-revenue-code.

[22] Chandra Wallace, “Corporate AMT Comment Letters Rich in Detail – And Disagreement,” Tax Notes, Mar. 22, 2023, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-today-federal/corporate-alternative-minimum-tax/corporate-amt-comment-letters-rich-detail-and-disagreement/2023/03/22/7g804.

[23] IRS, “IRS Grants Penalty Relief for Corporations That Did Not Pay Estimated Tax Related to the New Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax,” Jun. 7, 2023, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/irs-grants-penalty-relief-for-corporations-that-did-not-pay-estimated-tax-related-to-the-new-corporate-alternative-minimum-tax; IRS, “Relief from Certain Additions to Tax for Corporation’s Underpayment of Estimated Income Tax under Section 6655,” Notice 2023-42, Jun. 7, 2023, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-23-42.pdf.

[24] Chandra Wallace, “IRS Counsels Patience on Corporate AMT Guidance,” Tax Notes, Mar. 2, 2023, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-today-federal/corporate-alternative-minimum-tax/irs-counsels-patience-corporate-amt-guidance/2023/03/02/7g07k; Chandra Wallace, “Treasury Undecided on Further Interim Guidance for Corporate AMT,” Tax Notes, Mar. 8, 2023, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-today-federal/corporate-alternative-minimum-tax/treasury-undecided-further-interim-guidance-corporate-amt/2023/03/08/7g43q.

[25] IRS, “Initial Guidance Regarding the Application of the Excise Tax on Repurchases of Corporate Stock Under Section 4501 of the Internal Revenue Code,” Notice 2023-2, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-23-02.pdf

[26] Jennifer Williams-Alvarez, “U.S. Buyback Tax Could Hit More Foreign Firms Than First Expected,” The Wall Street Journal, Apr. 14, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-buyback-tax-could-hit-more-foreign-firms-than-first-expected-e9dedec3.

[27] IRS, “Transitional Guidance with Respect to Stock Repurchase Excise Tax,” Announcement 2023-18, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/a-23-18.pdf.

[28] Alon Brav, John Graham, Campbell R. Harvey, and Roni Michaely, “Payout Policy in the 21st Century,” Journal of Financial Economics 77 (September 2005), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0304405X05000528; Tax Policy Center, “Raising Revenue from Corporations,” May 16, 2023, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/event/raising-revenue-corporations.

[29] Erica York, “Tax on Stock Buybacks a Misguided Way to Encourage Investment,” Tax Foundation, Sep. 10, 2021, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-on-stock-buybacks/.

[30] Alex Durante, “Stock Buyback Tax Would Hurt Investment and Innovation,” Tax Foundation, Aug. 12, 2022, https://taxfoundation.org/inflation-reduction-act-stock-buybacks/.

[31] Alex Muresianu, “Breaking Down the Inflation Reduction Act’s Green Energy Credits,” Tax Foundation, Sep. 14, 2022, https://taxfoundation.org/inflation-reduction-act-green-energy-tax-credits/.

[32] John Podesta, “Building a Clean Energy Economy: A Guidebook to the Inflation Reduction Act’s Investments in Clean Energy and Climate Action,” CleanEnergy.gov, January 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Inflation-Reduction-Act-Guidebook.pdf.

[33] EPA, “Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions,” U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions.

[34] Kyle Pomerleau, “Testimony: Temporary Policy in the Federal Tax Code,” Tax Foundation, Mar. 13, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/testimony-temporary-tax-policy/.

[35] Internal Revenue Service, “Prevailing Wage and Apprenticeship Initial Guidance Under Section 45(b)(6)(B)(ii) and Other Substantially Similar Provisions,” Notice 2022-61, Nov. 30, 2022, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2022/11/30/2022-26108/prevailing-wage-and-apprenticeship-initial-guidance-under-section-45b6bii-and-other-substantially.

[36] Internal Revenue Service, “Initial Guidance Establishing Program to Allocate Environmental Justice Solar and Wind Capacity Limitation Under Section 48(e),” Notice 2023-17, Feb. 13, 2023, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-23-17.pdf; Internal Revenue Service, “Energy Community Bonus Credit Amounts under the Inflation Reduction Act,” Notice 2023-29, Apr. 4, 2023, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-23-29.pdf; Internal Revenue Service, “Energy Community Bonus Credit Amounts Under the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022,” Notice 2023-45, Jun. 15, 2023, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-23-45.pdf.

[37] Internal Revenue Service, “Domestic Content Bonus Credit Guidance Under Section 45, 45Y, 48, and 48E,” Notice 2023-38, May 12, 2023, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-23-38.pdf.

[38] Internal Revenue Service, “Elective Pay and Transferability Frequently Asked Questions: Overview,” Jun. 14, 2023, https://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/elective-pay-and-transferability-frequently-asked-questions-overview.

[39] Scott Hodge, “’Monetizing’ Clean Energy Tax Credits Creates a Sham Market for Bad Policy,” Tax Foundation, Jul. 18, 2023, https://taxfoundation.org/irs-clean-energy-tax-credits/.

[40] Internal Revenue Service, “Sustainable Aviation Fuel Credit; Registration; Certificates; Request for Public Comments,” Notice 2023-06, Dec. 19, 2022, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-23-06.pdf.

[41] Natalie Houghtalen, “Hydrogen 101,” ClearPath, Feb. 11, 2021, https://clearpath.org/tech-101/hydrogen-101/.

[42] Internal Revenue Service, “IRS Issues Guidance and Updates Frequently Asked Questions Related to the New Clean Vehicle Critical Mineral and Battery Components,” Apr. 17, 2023, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/04/17/2023-06822/section-30d-new-clean-vehicle-credit.

[43] Chad Brown, “How the United States Solved South Korea’s Problems with Electric Vehicle Subsidies Under the Inflation Reduction Act,” Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper 23-6, July 2023, https://www.piie.com/publications/working-papers/how-united-states-solved-south-koreas-problems-electric-vehicle.

[44] Ibid; see also Internal Revenue Service, “Section 30D New Clean Vehicle Credit,” Mar. 31, 2023, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/04/17/2023-06822/section-30d-new-clean-vehicle-credit.

[45] Barbara Moens, Steven Overly, and Sarah Anne Aarup, “U.S. Pumps the Brakes on EU Clean Car Deal,” Politico, May 22, 2023, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/05/21/us-eu-clean-car-deal-00098092.

[46] Internal Revenue Service, “Submission of Information to IRS by Qualified Manufacturers of Clean Vehicles, Previously-Owned Clean Vehicles, and Commercial Clean Vehicles; Submission of Information to IRS by Sellers of Clean Vehicles and Previously-Owned Clean Vehicles,” Revenue Procedure 2022-42, Dec. 12, 2022, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-22-42.pdf; see also Internal Revenue Service, “Certain Definitions of Terms in Section 30D Clean Vehicle Credit,” Notice 2023-1, Dec. 29, 2022, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-23-01.pdf; Internal Revenue Service, “Certain Definitions of Terms in Section 30D Clean Vehicle Credit,” Notice 2023-16, Feb. 3, 2023, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-23-16.pdf.

[47] Internal Revenue Service, “Section 45W Commercial Clean Vehicles and Incremental Cost for 2023,” Notice 2023-9, Dec. 29, 2022, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-23-09.pdf; see also Internal Revenue Service, “Certain Definitions of Terms in Section 30D Clean Vehicle Credit.”

[48] Internal Revenue Service, “Frequently Asked Questions About Energy Efficient Home Improvements and Nonbusiness Energy Property Credits,” Fact Sheet 2022-40, Dec. 22, 2022, https://www.irs.gov/pub/taxpros/fs-2022-40.pdf.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Brendan McDermott, “Residential Energy Tax Credits: Changes in 2023,” Congressional Research Service, Nov. 21, 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN12051.

[51] Dave Sobochan and Mike McGivney, “15 Takeaways from the Inflation Reduction Act’s Clean Energy Tax Incentives,” Cohen & Co., Aug. 26, 2022, https://www.cohencpa.com/knowledge-center/insights/august-2022/15-takeaways-from-the-inflation-reduction-act-clean-energy-tax-incentives.

[52] Alex Muresianu, “How Expensing for Capital Investment Can Accelerate the Transition to a Cleaner Economy,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 12, 2021, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/energy-efficiency-climate-change-tax-policy/.

[53] Internal Revenue Service, “Prevailing Wage and Apprenticeship Initial Guidance Under Section 45(b)(6)(B)(ii) and Other Substantially Similar Provisions.”

[54] Clean Air Task Force, “Carbon Capture and the Inflation Reduction Act,” Aug. 19, 2022, https://cdn.catf.us/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/16093309/ira-carbon-capture-fact-sheet.pdf.

[55] Barbara S. de Marigny, “Firm Notes Ambiguity in Carbon Oxide Sequestration Credit Provisions,” Baker Botts LLP, Jun. 8, 2023, https://www.taxnotes.com/research/federal/other-documents/irs-tax-correspondence/firm-notes-ambiguity-in-carbon-oxide-sequestration-credit-provisions/7h1c4?highlight=De%20Marigny%20Barbara#7h1c4-0000009.

[56] Internal Revenue Service, “Initial Guidance Establishing Qualifying Advanced Energy Project Credit Allocation Program Under Section 48(e),” Notice 2023-18, Feb. 13, 2023, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-23-18.pdf.

[57] Diana DiGangi, “Treasury Issues Further Guidance for IRA’s $10B Tax Credit Incentivizing Clean Energy Manufacturing,” Utility Dive, Jun. 1, 2023, https://www.utilitydive.com/news/ira-clean-energy-manufacturing-tax-credit-ten-billion-irs-guidance/651807/.

[58] Ibid; Internal Revenue Service, “Additional Guidance for the Qualifying Advanced Energy Project Credit Allocation Program under Section 48C(e),” Notice 2023-44, May 31, 2023, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-23-44.pdf;

[59] International Energy Agency, “Inflation Reduction Act 2022: Sec. 13502 Advanced Manufacturing Production Credit,” May 24, 2023, https://www.iea.org/policies/16282-inflation-reduction-act-2022-sec-13502-advanced-manufacturing-production-credit.

[60] Internal Revenue Service, “Treasury, IRS Issue Guidance for the Advanced Manufacturing Investment Credit,” Jun. 14, 2023, https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/treasury-irs-issue-guidance-for-the-advanced-manufacturing-investment-credit.