Table of Contents

- Key Findings

- Introduction

- Global Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Is Weak

- Taxes on Foreign Earnings Influence Business Investment Decisions

- A Simple Example of Taxes on Global Companies and Investment Decisions

- A Lesson from Puerto Rico

- The Options on the Table

- — The OECD Pillar Two Blueprint

- — The Biden Proposal

- Mitigating Negative Impacts: Leaving Substance Alone

- Conclusion

Launch U.S. International Tax Reform Resource Center

Key Findings

- The political effort to address profit shiftingProfit shifting is when multinational companies reduce their tax burden by moving the location of their profits from high-tax countries to low-tax jurisdictions and tax havens. and limit the benefits of using low-tax jurisdictions to facilitate cross-border investment has focused on adopting a global minimum tax applicable to large multinational corporations.

- While a global minimum tax could act as a backstop to current corporate tax rules, it would also increase the tax burden on business investment across the world.

- The experience of U.S. companies following the elimination of a tax benefit connected to Puerto Rico shows that policies that increase the taxes owed on offshore operations can have negative blowback effects on domestic markets.

- Because foreign direct investment (FDI) is sensitive to tax rates, a global minimum tax would directly impact investment decisions of multinational companies.

- To mitigate the negative economic effects of a global minimum tax, policymakers should ensure that both the minimum rate and the tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. to which it applies are designed in a way that does not distort investment decisions but still acts as a backstop to current corporate tax rules.

Introduction

Leaders around the world are quickly moving to finalize an agreement on a global minimum tax in 2021, based on the so-called “Pillar Two” proposal from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).[1] The agreement would limit tax competition and the “race to the bottom” on corporate tax rates by putting a floor on effective tax rates applied to cross-border investment by large multinational corporations.

A global minimum tax would increase corporate tax revenues collected by governments around the world. One version of a minimum tax with a 15 percent rate would raise roughly $70 billion in new tax revenues according to analysis by economists at the OECD.[2]

These higher tax revenues would, however, come at a price of lower global investment. Businesses that currently utilize low-tax jurisdictions to facilitate cross-border investment would see a significant tax hike on their current projects and face a new tax deterrent on future projects—an effect ignored by many policymakers.

The result would be less foreign direct investment (FDI) and slower global economic growth.

However, many policymakers are prioritizing tax revenues ahead of investment and growth.

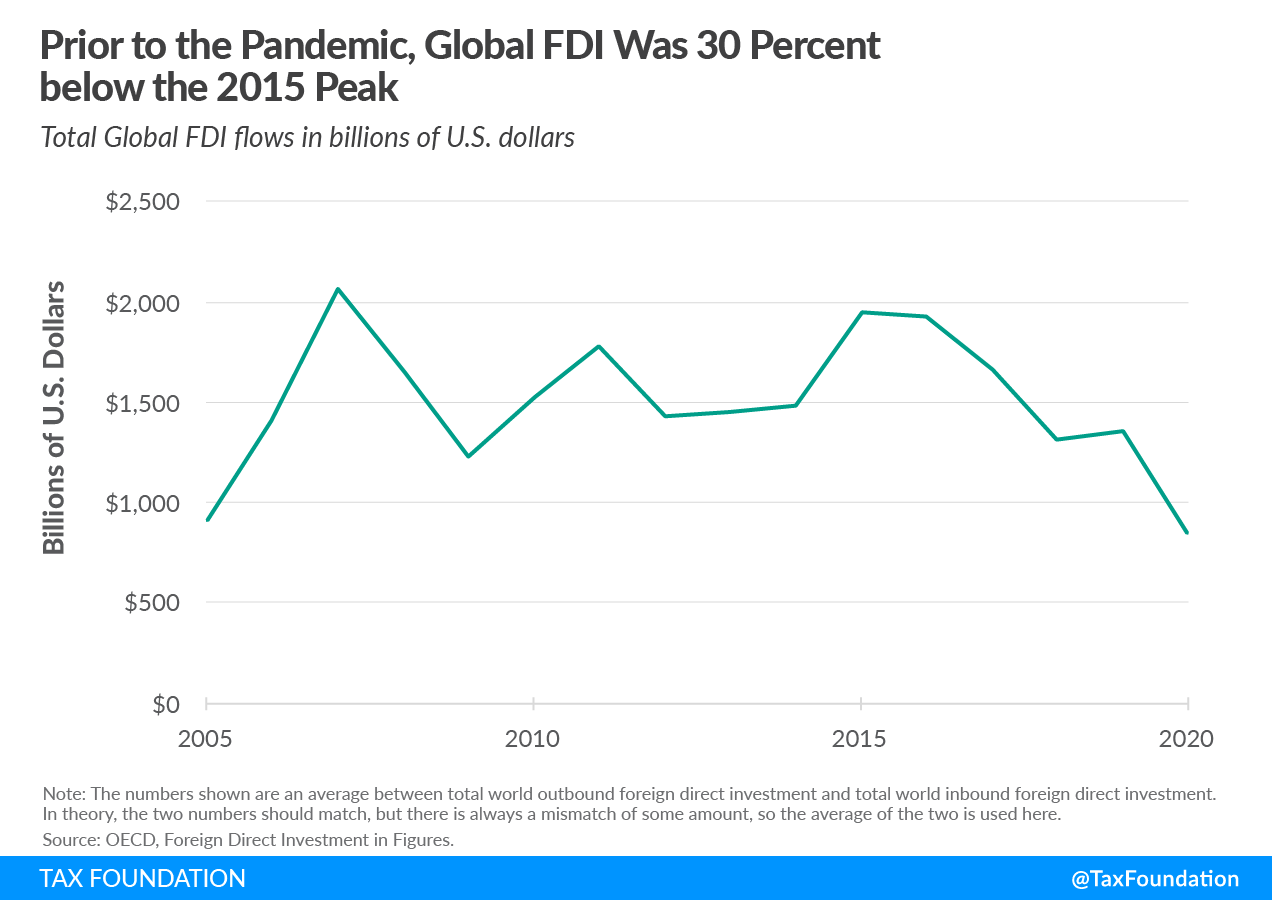

Growth in global FDI had stalled prior to the pandemic, and FDI fell by 38 percent in 2020 to its lowest level since 2005.[3]

A significant share of global FDI flows through jurisdictions with low corporate tax rates, facilitating investments by companies in both developed and developing countries.[4] Eliminating the tax benefits of structuring investments through these jurisdictions would directly impact business incentives to invest across borders.

Understanding how a global minimum tax might negatively impact cross-border investment and how to avoid that outcome will be critical if global FDI is to fully recover following the pandemic.

The companies targeted by a global minimum tax have a significant economic footprint across the world. As of 2018, U.S. multinational firms employed 28.6 million workers in the U.S. and 14.4 million in the rest of the world.[5] Other countries also have sizable companies with a global footprint.[6]

The international success of U.S. companies has meaningful impacts at home. When investing abroad, companies are commonly extending or replicating their operations to reach foreign markets.[7]

When U.S. companies succeed in reaching foreign customers, that can mean more investment in domestic activities and more hiring at home.[8] Recent research has shown that when a U.S. multinational increases hiring abroad, 67 percent of the time the company also increases employment in the U.S.[9] The U.S. economy is also dynamic. Even when a company chooses to offshore jobs, other employers may increase their job openings, with an overall net positive effect on U.S. employment.[10]

A harmful global minimum tax could therefore threaten jobs and investment both abroad and at home.

This paper lays out some examples and lessons for policymakers to consider when discussing the impact of low-tax jurisdictions, policies meant to curb tax avoidance, and ways to mitigate negative impacts of a global minimum tax on investment.

Of the main global minimum tax proposals currently being discussed, the Biden administration proposal to significantly increase the tax burden on Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI) is likely to be most harmful to cross-border investment decisions.[11] The Pillar Two policy laid out in a blueprint from the OECD would be somewhat less harmful.[12]

This paper offers a third design which would mitigate the most problematic impacts on cross-border investment decisions.[13] This would require a minimum tax with a true minimum base that allows businesses to fully deduct investment and employment costs and would essentially be a tax on cash flows that are taxed below the minimum rate.

Globalization has lowered barriers to trade and investment across the globe and facilitated development that has lifted millions out of poverty. Policies that create new barriers to cross-border investment could act as a burden on the global economic recovery and the next wave of global development.

It is imperative that policymakers negotiating new international tax rules choose policies that facilitate trade and investment rather than stand in their way to the harm of workers and consumers across the globe. A poorly designed global minimum tax could do just that.

Global Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Is Weak

The global minimum tax debate enters the scene at a weak time for the global economy. Following a peak of nearly $2 trillion in global FDI flows in 2015, worldwide cross-border investment fell in four out of the last five years. The most recent numbers from the pandemic economy of 2020 shows global FDI at a level below 2005.

As will be discussed, cross-border investment is sensitive to tax policy, and a global minimum tax will likely make firms more sensitive to taxes when choosing whether to expand abroad to reach foreign customers. This would be especially true for small and growing firms if they are also caught by the new rules.[14]

As mentioned in the Introduction, a significant share of global FDI is channeled through low-tax jurisdictions that are often referred to as investment hubs.[15] And evidence suggests that larger firms are more likely to use business structures that benefit from those low-tax jurisdictions.[16]

Some policymakers look at the role that lower-tax jurisdictions play in the global economy and simply see lost tax revenues. Many developing countries in particular see companies utilizing low-tax jurisdictions and tax treaty benefits to facilitate earning very low tax profits on their investments.[17]

These viewpoints have undergirded proposals for a global minimum tax. On the one hand, a minimum tax would eliminate many of the benefits of channeling investments through low-tax jurisdictions or exploiting tax treaties to pay low taxes on cross-border income streams. However, such a policy would not be without consequences.

Taxes on Foreign Earnings Influence Business Investment Decisions

A significant body of research has revealed that companies are sensitive to tax rates when making decisions about where to invest when they expand globally.

One of the more recent pieces of this research is from three economists in Dublin, Ireland, who find that smaller businesses are more sensitive to high tax rates than larger firms when making cross-border investment decisions.[18] The authors believe this may be because larger companies have more opportunities to minimize their exposure to high foreign taxes by utilizing low-tax jurisdictions.

This differential impact for large and small businesses is also found in OECD research on tax sensitivity by firm profitability.[19] They find that tax sensitivity of investment by companies with more than a 10 percent profit margin is half that of companies with a profit margin between 0 and 10 percent. This means that more profitable companies might not be as impacted by tax policy changes.

If larger and more profitable companies are currently less sensitive to tax rates due to access to low-tax jurisdictions, it is likely that policies designed to essentially block that access with higher taxes (such as a global minimum tax) will lead those businesses to be more sensitive to tax rates.[20]

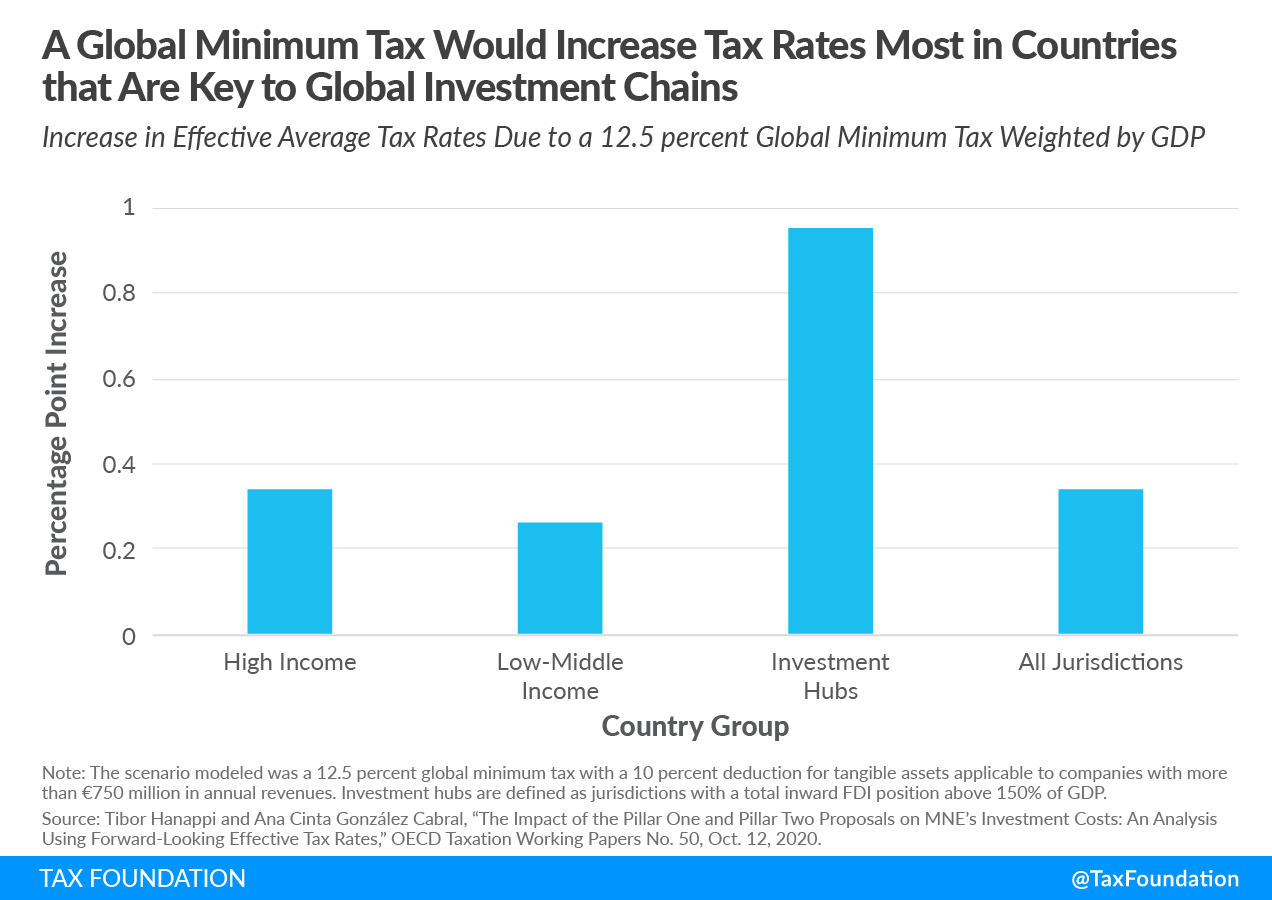

The OECD’s economic impact assessment of one possible version of the global minimum tax found that the policy would have the largest increase in effective average tax rates for investment hubs.[21]

Cross-border investment decisions are sensitive to effective average tax rates.[22] Companies more exposed to a global minimum tax will likely respond by changing their investment behavior. These changes could result in both foreign and domestic reductions in operations and employment with spillover effects to the local communities where they are located.

A global minimum tax would not be the first policy effort to increase tax rates on the foreign earnings of companies; far from it. In recent years, countries have adopted several policies to counter companies’ efforts to minimize their tax bills utilizing low-tax jurisdictions.

Tax Foundation Policy Analyst Elke Asen recently found in a review of the existing academic literature that these policies not only have revenue implications but they also change investment behavior for companies.[23]

In some cases, the policies act like a direct taxA direct tax is levied on individuals and organizations and cannot be shifted to another payer. Often with a direct tax, such as the personal income tax, tax rates increase as the taxpayer’s ability to pay increases, resulting in what’s called a progressive tax. increase on foreign subsidiaries, and companies respond by reducing investment in the subsidiaries most impacted (while maintaining overall investment levels).[24] Other policies meant to address tax avoidance by limiting the deductibility of interest payments lead to negative employment and investment effects. A study of German multinational companies found that FDI falls by 2.5 percent if a policy to limit interest deductibility is adopted by a country with an above-average corporate tax rate.[25]

A Simple Example of Taxes on Global Companies and Investment Decisions[26]

Imagine two businesses that are deciding where to invest and expand their operations abroad. One large company utilizes low-tax jurisdictions to minimize the amount of taxes it pays wherever its investments are located. Because of this it consistently pays an effective tax rate of 5 percent regardless of where its operations are in the world.

The other company is smaller and pays close attention to the taxes it pays because it does not have the resources or the business model that would allow it to channel its investments through low-tax jurisdictions.

If taxes were not part of the picture, both companies would invest in a country that has the best infrastructure, labor market, and proximity to foreign customers.

With taxes, though, perhaps the two businesses may choose different locations for their investment.

Now imagine that there are two countries where these businesses might choose to locate their investments. One country has a high corporate tax rate of 25 percent, and it has some of the best infrastructure, skilled workers, and market potential in the world.

The other country has a corporate tax rate of 10 percent. It has lower quality infrastructure and a less skilled work force, and it is not as well-situated to access foreign customers.

Because the large business can use low-tax jurisdictions to minimize its overall tax burden, it will invest in the high-tax country with the resources and location that best fit its needs.

The smaller business might choose the country with the 10 percent corporate tax rate. The business owners may think that the money it will save on taxes will more than make up for the costs of improving the lower quality infrastructure and investing in training the existing workforce.

How would a 15 percent global minimum tax change the decisions of these hypothetical companies?

Both companies will face tax hikes. The large business will face at least a 15 percent rate on its investment in the high-tax country, and the small business will face a 15 percent rate on its investment in the country with a 10 percent corporate tax.

After accounting for the new tax costs, the large business may continue to have operations in the high-tax country, but it reduces its plans to further expand foreign operations while cutting back roles in its home country that support foreign operations.

If the new tax costs are sufficiently high, the small business may be deterred from future cross-border investment altogether and may sell off current foreign operations to other companies. Like the large company, the small company may also shrink domestic operations that previously supported foreign sales.

In both cases, future foreign investment is stunted, and domestic investment is impacted as well.

A Lesson from Puerto Rico

One lesson from recent U.S. policy history provides some important insights into the context of understanding the economic impacts of eliminating the benefits of low-tax jurisdictions.

In 1996, the U.S. government began a 10-year phaseout of a tax benefit for U.S. companies with activities and profits in Puerto Rico. The policy, which was embedded in section 936 of the Internal Revenue Code, provided U.S. companies with operations or assets in Puerto Rico an opportunity to essentially eliminate federal tax on profits earned in Puerto Rico.

As Tax Foundation economists have written previously:

In addition to section 936, the Puerto Rican corporate tax code gave significant incentives for U.S. corporations to locate subsidiaries on the island. Puerto Rican tax law allowed a subsidiary that was more than 80 percent owned by a foreign entity to deduct 100 percent of the dividends paid to its parent. As such, subsidiaries in Puerto Rico had no corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. liability as long as their profits were distributed as dividends.[27]

This made Puerto Rico a popular spot for U.S. companies to put intangible assets or factories while keeping complementary activities in the continental United States. The low-tax manufacturing and other activities in Puerto Rico effectively lowered the cost of investing those profits back into complementary activities in places like Ohio or New York.

When the benefit began to phase out after 1996, things began to change. Recent research by Duke University economist Juan Carlos Suárez Serrato highlights how eliminating the tax haven status of Puerto Rico changed the game for U.S. companies.[28] Rather than having tax-free income channeled through Puerto Rico, U.S. companies quickly faced the full freight of the U.S. corporate tax with a federal statutory rate of 35 percent. As the tax costs rose, investment and hiring decisions were directly impacted.

According to Suárez Serrato, companies benefiting from section 936 “accounted for about 2.3 million jobs in the US and that the 682 firms with Puerto Rican affiliates employed close to 11 million workers in the US. Many of these firms are in the chemical, food, and electronic manufacturing industries.” As he puts it, “firms viewed the repeal of section 936 as an increase in the effective cost of investing in the US.”

Suárez Serrato estimates that the companies most exposed to the policy change saw effective tax rates rise by 4.65 to 6 percentage points. This translated into reduced global investment of 10 percent and reduced U.S. employment by 6.7 percent by these affected companies.

Global firms are also local companies scattered across the map in both large and small towns. When a local firm that has a global reach faces a large tax hike that leads to local reductions in employment, there can be spillover effects on the surrounding services and suppliers to the larger company.

Suárez Serrato explores the local impacts of the jobs lost due to the elimination of section 936. When a company eliminated a local job due to the repeal of section 936, that single layoff led to an estimated 3.57 other local jobs being lost. He also found “relative decreases in wage rates that are concentrated in the wages of workers without a college degree as well as decreases in housing prices and rental costs.”

Suárez Serrato also finds reduced job growth, more unemployment benefits, and higher dependency on income support programs in U.S. counties where firms most affected by the policy change were located.

The repeal of section 936 shows, as Suárez Serrato argues, that addressing the use of low-tax jurisdictions to minimize tax payments is not simply a question of revenues. In fact, the domestic economic blowback from increasing taxes on foreign income can be severe. Puerto Rico has suffered as well.[29]

The main lesson is that while policies can address the use of low-tax jurisdictions by multinational companies, this is accomplished by increasing the cost of investing and hiring. Taking the various approaches to addressing tax avoidance and unifying the effort with a global minimum tax could have negative impacts throughout the world.

However, countries could also choose a design for the global minimum tax that mitigates these effects.

The Options on the Table (Global Minimum Tax)

Discussions at the international level are ongoing and current uncertainties mean it is impossible to know exactly what sort of global minimum tax countries might agree on. However, the OECD laid out a blueprint in 2020 that is likely the basis for current discussions, and the Biden administration has also outlined its own approach.

The OECD Pillar Two Blueprint

The policy outlined by the OECD in 2020 would have two tools for implementing a global minimum tax.[30] The first, an income inclusion rule, would allow countries to tax the foreign earnings of their companies at a minimum rate. The second, an undertaxed payments rule, would allow countries to deny deductions for payments made by a subsidiary to its parent company (or other related entity) in a foreign jurisdiction that had a low effective tax rate on business income.

Countries that adopt both policies would ensure that any business that had operations in its jurisdictions (either as a headquarters or a subsidiary of a foreign company) would pay at least the minimum rate of tax.

A minimum tax must have a specific rate and base, though. The OECD’s economic impact assessment analyzed several options for the rate ranging from 7.5 percent to 17.5 percent.[31]

The tax base would begin with profits reported on public financial statements and adjusted for both temporary and permanent differences between financial profits and taxable profits. The proposal contemplates providing a deduction for economic substance measured by a percentage of tangible asset value and employment costs. Specific percentages were not offered in the blueprint, although the economic impact assessment modeled a 10 percent deduction for tangible assets.

A deduction for economic substance like tangible assets including factories, distribution centers, and research and development facilities along with employment costs makes sense. Such a deduction is meant to reduce the impact of the global minimum tax on decisions of hiring and investing across borders.

The OECD blueprint also outlined how a revenue threshold might be used to target the largest companies. For instance, if policymakers agreed on a €750 million annual revenue threshold for applying the rules, then the policy would avoid some of the distortive impacts on smaller businesses. Companies that grow to surpass the threshold could see a cliff effect where in one year they move from being below the threshold to being large enough that the global minimum tax would apply to them.

However, the U.S. has proposed something that is quite different and likely much more burdensome to the global success of U.S. companies.

The Biden Proposal

Since 2017, the U.S. has had a formulaic tax on the foreign earnings of U.S. companies. The tax is levied on Global Intangible Low-Tax Income (GILTI) which amounts to 50 percent of net foreign earnings after a 10 percent deduction for foreign assets (like the deduction for economic substance contemplated in the OECD proposal).

In theory, GILTI works as a minimum tax with a rate ranging from 10.5 percent to 13.125 percent depending on a company’s exposure to foreign taxes. In practice, it often operates as a surtaxA surtax is an additional tax levied on top of an already existing business or individual tax and can have a flat or progressive rate structure. Surtaxes are typically enacted to fund a specific program or initiative, whereas revenue from broader-based taxes, like the individual income tax, typically cover a multitude of programs and services. on the foreign earnings of U.S. companies with total effective tax rates on foreign earnings approaching (if not exceeding) the U.S. statutory rate of 21 percent.[32]

Unfortunately, the problems with GILTI that lead to these unintended results are likely to be made worse if President Biden’s proposals become law.

The Biden proposal would significantly increase the tax burden on the foreign earnings of U.S. companies with changes to GILTI.[33] Tax Foundation modeling has shown that the tax liability U.S. companies face on their foreign earnings could nearly triple over the next decade.[34]

The Biden proposal would change GILTI in several ways. First, it would increase the nominal tax rate from 10.5 percent to 21 percent.[35] Second, it would eliminate the deduction for foreign tangible assets. Third, the proposal would require GILTI to be calculated for each country where a U.S. company has profits rather than the current approach that allows all foreign earnings to be blended before calculating tax liability.

Relative to the OECD blueprint on a global minimum tax, the Biden approach on GILTI would have a high effective tax rate and a broad base. Both elements would negatively impact hiring and investment decisions by U.S. companies both inside the U.S. and abroad.

The U.S. administration has also proposed something that would work like the undertaxed payments rule in the OECD blueprint. The administration has proposed a policy named “Stopping Harmful Inversions and Ending Low-Tax Developments” (or SHIELD) as a tool to deny deductions for cross-border payments made by U.S. subsidiaries to a related party in a different country if that other country does not operate a global minimum tax.[36]

In international negotiations the U.S. Treasury has suggested that a global agreement should rely on a minimum effective tax rate of at least 15 percent. If such a policy were agreed to and the U.S. were to implement Biden’s proposed changes to GILTI, U.S. companies would face a more significant tax burden on their foreign operations than companies based in other countries.

This would put U.S. companies at a competitive disadvantage when seeking new markets and customers abroad and could lead to a shrinking global footprint of U.S. firms. Such a change would also reduce the domestic footprint of U.S. companies with impacts in communities across the country that are home to local, but globally successful, U.S. companies.

A global minimum tax does not need to be quite so harmful, however. In the following section I discuss one option to minimize the effect of a global minimum tax on investment decisions by companies, which could help to avoid stunting a recovery in global FDI and economic blowback on domestic jobs and hiring.

Mitigating Negative Impacts: Leaving Substance Alone

The best way to mitigate the negative impacts on cross-border investment and domestic blowback from the adoption of a global minimum tax is to design it with investment decisions in mind.

Economic models can show both how distortive a corporate tax change can be to investment decisions and how to avoid those distortions. One approach is to design the tax in a way that fully exempts business costs including start-up costs, ongoing employment costs, and the costs of expansion and new hiring.

While countries differ in their approaches to taxing businesses, few do it in a way that fully exempts these various costs. When those costs are not exempt, taxable income is inflated, and hiring and investment decisions are distorted. A policy that fully exempts those costs removes the distortions.

Economists refer to this type of tax as a tax on cash flow because taxes are only charged when cash (profit) moves out of a business. If a business reinvests its profits for new hiring or an expansion, there is no recognized profit for tax purposes.

Countries like Latvia, Estonia, and Georgia have adopted this type of corporate tax policy for two reasons. First, it is simple both from an administration and compliance standpoint. Second, it is a policy that is neutral to investment choices. If a company has a profitable investment opportunity, there is no tax wedge to distort that investment. However, if investors require a dividend or owners want to take cash out of the business for some reason, then that is when the tax is due.

In the context of a global minimum tax, a similar approach was suggested in 2013 by economists Harry Grubert and Rosanne Altshuler.[37] Their recommendation was for the U.S. to adopt a minimum tax on foreign earnings of U.S. companies and for that policy to fully exempt the costs of new investment (i.e., full expensing of capital).

The recommendation they made for the U.S. should be extended to the ongoing global negotiations.

In fact, a leaked draft version of the global minimum tax blueprint mentioned using full expensingFull expensing allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of certain investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings. It alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. of capital investment to avoid having the minimum tax cause new distortions to investment decisions.[38] In the blueprint that was released in October 2020, however, that option had been discarded in favor of a formula that would provide a deduction for tangible assets and employment costs.[39]

A deduction defined by a formula would be valuable although it is unlikely that it would fully offset the distortion of a global minimum tax, as it would not always accurately capture the costs of business inputs.

Other features of a minimum tax, which were included in the Pillar Two blueprint, include loss carryforwards and carryovers for foreign tax credits.[40] Both of these reduce the likelihood that one good year for a company would trigger global minimum tax liability and instead tax liability would be smoothed out over time.

Taken together, this policy approach would ensure that the global minimum tax applies to profits that are above and beyond normal economic returns on investment and cyclical fluctuations in foreign income. It would minimize distortions to new cross-border investment while collecting taxes on high value activities that are in tax jurisdictions that do not operate a global minimum tax themselves or do not have a corporate tax at all.

Conclusion

The global economy is currently weak, but a recovery is on the way. Policy discussions underway at the international level have the potential to either facilitate or dampen the recovery.

A high global minimum tax rate applied to a broad base of foreign earnings would have negative impacts on foreign investment decisions and result in economic blowback on countries implementing the policy. A policy like the one proposed by the Biden administration could have particularly severe effects for U.S. companies.

However, a minimum tax that acts more as a limited backstop to current corporate tax rules would have less harmful effects. If the minimum tax is applied to a tax base that fully exempts investment and employment costs, then it will be less distortive to business hiring and investment decisions.

The lessons of recent years in cross-border tax policy show clearly that businesses respond to higher taxes even when those policies are targeted at their foreign earnings.

The U.S. and other governments should avoid the temptation of focusing simply on potential revenues raised by a global minimum tax and instead account for the negative impacts on the U.S. and global economy if the recovery in cross-border investment were to stall in the coming years.

[1] OECD, “Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Report on Pillar Two Blueprint,” Oct. 14, 2020, https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/tax-challenges-arising-from-digitalisation-report-on-pillar-two-blueprint-abb4c3d1-en.htm.

[2] For the global minimum tax, the OECD modeled multiple rates to estimate the global revenue impacts while excluding U.S.-based multinationals which are already facing a form of a minimum tax. The revenue estimates range from about $20 billion for a 7.5 percent minimum tax rate to $87.5 billion for a 17.5 percent minimum tax rate. The OECD reports the revenue increase as a share of global corporate income tax revenues in Table 3.13 in OECD, “Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Economic Impact Assessment,” Oct. 12, 2020, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/0e3cc2d4-en.

[3] OECD, “Foreign Direct Investment in Figures,” accessed June 2, 2021, https://www.oecd.org/daf/inv/investment-policy/investmentnews.htm.

[4] Antonio Coppola et al., “Redrawing the Map of Global Capital Flows: The Role of Cross-Border Financing and Tax Havens,” April 2021, https://www.globalcapitalallocation.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/CMNS-Paper.pdf.

[5] Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Activities of U.S. Multinational Enterprises, 2018,” Aug. 21, 2020, https://www.bea.gov/news/2020/activities-us-multinational-enterprises-2018.

[6] C. Fritz Foley et al., Global Goliaths: Multinational Activity in the Modern World (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2021), https://www.brookings.edu/book/global-goliaths/.

[7] Ronald B. Davies and James R. Markusen, “The Structure of Multinational Firms’ International Activities,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 26827, Mar. 9, 2020, https://doi.org/10.3386/w26827.

[8] Evidence on this can be found in Mihir A. Desai, C. Fritz Foley, and James R. Hines Jr., “Foreign Direct Investment and Domestic Economic Activity” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 11717, Oct. 24, 2005, https://doi.org/10.3386/w11717, and Mihir A. Desai, C. Fritz Foley, and James R. Hines Jr., “Foreign Direct Investment and the Domestic Capital Stock,” American Economic Review 95:2 (May 2005), https://doi.org/10.1257/000282805774670185.

[9] Foley et al., Global Goliaths: Multinational Activity in the Modern World.

[10] Brian Kovak, Lindsay Oldenski, and Nicholas Sly, “The Positive and Negative Effects of Offshoring on Domestic Employment,” VoxEU.Org, Jan. 15, 2018, https://www.voxeu.org/article/positive-and-negative-effects-offshoring-domestic-employment .

[11] U.S. Treasury, “General Explanations of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2022 Revenue Proposals,” May 2021, https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/General-Explanations-FY2022.pdf.

[12] OECD, “Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Report on Pillar Two Blueprint.”

[13] This recommendation is inspired by a proposal for the U.S. made in Harry Grubert and Rosanne Altshuler, “Fixing the System: An Analysis of Alternative Proposals for the Reform of International Tax,” Social Science Research Network, Apr. 1, 2013, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2245128.

[14] The U.S. rules that tax foreign earnings of companies apply equally to small and large companies. So, President Biden’s proposal to increase the tax burden on GILTI would impact multinational firms regardless of their size. However, the blueprint for Pillar Two offered by the OECD would target multinational firms above a size threshold (such as €750 million in annual global revenues) to try to mitigate effects on smaller companies. A size threshold could also result in a cliff effect where a small company would potentially face a higher tax burden as it grows to cross the threshold.

[15] The OECD defines an investment hub as having a total inbound FDI position greater than 150 percent of gross domestic product.

[16] Ronald B. Davies, Iulia Siedschlag, and Zuzanna Studnicka, “The Impact of Taxes on the Extensive and Intensive Margins of FDI,” International Tax and Public Finance 28 (April 2021): 434–464, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-020-09640-3.

[17] For a thorough discussion of the tax treaty challenges of developing countries, see Sébastien Leduc and Geerten Michielse, “Chapter 8: Are Tax Treaties Worth It for Developing Economies,” in Ruud A. de Mooij, Alexander D. Klemm, and Victoria J. Perry, Corporate Income Taxes under Pressure: Why Reform Is Needed and How It Could Be Designed, (Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund, 2021), https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/books/071/28329-9781513511771-en/28329-9781513511771-en-book.xml.

[18] Davies, Siedschlag, and Studnicka, “The Impact of Taxes on the Extensive and Intensive Margins of FDI.”

[19] Valentine Millot et al., “Corporate Taxation and Investment of Multinational Firms: Evidence from Firm-Level Data,” OECD Taxation Working Papers No. 51, Oct. 12, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1787/9c6f9f2e-en.

[20] See Sébastien Leduc and Geerten Michielse, “Chapter 11: Strengthening Source-Based Taxation” in de Mooij, Klemm, and Perry, Corporate Income Taxes under Pressure.

[21] The scenario modeled was a 12.5 percent global minimum tax with a 10 percent deduction for tangible assets applicable to companies with more than €750 million in annual revenues. Tibor Hanappi and Ana Cinta González Cabral, “The Impact of the Pillar One and Pillar Two Proposals on MNE’s Investment Costs: An Analysis Using Forward-Looking Effective Tax Rates,” OECD Taxation Working Papers No. 50, Oct. 12, 2020, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/taxation/the-impact-of-the-pillar-one-and-pillar-two-proposals-on-mne-s-investment-costs_b0876dcf-en.

[22] Davies, Siedschlag, and Studnicka, “The Impact of Taxes on the Extensive and Intensive Margins of FDI.”

[23] Elke Asen, “What We Know: Reviewing the Academic Literature on Profit Shifting,” Tax Notes International 102 (May 24, 2021), https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-international/base-erosion-and-profit-shifting-beps/what-we-know-reviewing-academic-literature-profit-shifting/2021/05/24/60lj4.

[24] Ruud de Mooij and Li Liu, “At a Cost: The Real Effects of Transfer Pricing Regulations,” IMF Economic Review 68:1 (March 2020): 268–306, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41308-019-00105-0.

[25] Thiess Buettner, Michael Overesch, and Georg Wamser, “Anti Profit-Shifting Rules and Foreign Direct Investment,” International Tax and Public Finance 25:3 (June 2017): 553–580, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-017-9457-0.

[26] Credit is due to Dr. Ron Davies at University College Dublin for inspiring this example in an email exchange with the author.

[27] Scott Greenberg and Gavin Ekins, “Tax Policy Helped Create Puerto Rico’s Fiscal Crisis” Tax Foundation, June 30, 2015, https://www.taxfoundation.org/tax-policy-helped-create-puerto-rico-fiscal-crisis/.

[28] Juan Carlos Suárez Serrato, “Unintended Consequences of Eliminating Tax Havens” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 24850, July 23, 2018, https://doi.org/10.3386/w24850.

[29] Greenberg and Ekins, “Tax Policy Helped Create Puerto Rico’s Fiscal Crisis.”

[30] OECD, “Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Report on Pillar Two Blueprint.”

[31] OECD, “Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Economic Impact Assessment.”

[32] Daniel Bunn, “U.S. Cross-Border Tax Reform and the Cautionary Tale of GILTI,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 17, 2021, https://www.taxfoundation.org/gilti-us-cross-border-tax-reform/.

[33] U.S. Treasury, “General Explanations of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2022 Revenue Proposals.”

[34] Cody Kallen, “Effects of Proposed International Tax Changes on U.S. Multinationals” Tax Foundation, Apr. 28, 2021, https://www.taxfoundation.org/biden-international-tax-proposals/.

[35] The effective rate would be significantly higher. See Bunn, “U.S. Cross-Border Tax Reform and the Cautionary Tale of GILTI.”

[36] U.S. Treasury, “General Explanations of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2022 Revenue Proposals.”

[37] Grubert and Altshuler, “Fixing the System.”

[38] OECD, “Draft Report on Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Report on Pillar Two Blueprint,” 2020, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e77862f852cc823ab60c76a/t/5f514161f5864d37d303337b/1599160678490/Draft+report+-+Pillar+2+Blueprint.pdf.

[39] OECD, “Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Report on Pillar Two Blueprint.”

[40] Ibid.

Share this article