Key Findings:

- Congress is considering comprehensively reforming the federal taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. code. Leading proposals include the GOP Blueprint offered by House Republicans and the campaign tax plan put forward by President Trump. The plans share a number of similarities, but vary in terms of how they would change federal tax bases.

- States, for administrative simplicity for both the state and taxpayers, tend to tie their tax codes to the federal tax code. Because of this conformity, changes made to federal definitions, such as adjusted gross incomeFor individuals, gross income is the total of all income received from any source before taxes or deductions. It includes wages, salaries, tips, interest, dividends, capital gains, rental income, alimony, pensions, and other forms of income. For businesses, gross income (or gross profit) is the sum of total receipts or sales minus the cost of goods sold (COGS)—the direct costs of producing goods, including inventory and certain labor costs. (AGI), influence the revenue that states collect.

- Twenty-seven states use federal AGI as their income tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates. , six states use federal taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. Taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. , and three states use gross income. Forty-one states conform to federal definitions of corporate income, either before or after net operating losses.

- State individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. revenues would likely increase due to the large base expansion occurring at the federal level, but revenue changes from corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. modification is less straightforward. However, the magnitude of revenue of the individual income tax changes would likely be larger than any possible revenue losses from corporate income tax reform.

- States have a number of options available to react to any revenue impacts from federal tax reform, such as phase-ins, tax triggers, and contingent enactment clauses. States can also look at ways to reform their tax codes in tandem to further mitigate any deleterious effects. Federal tax reform presents an opportunity for states to consider ways to improve their own tax structures, as was the case with the 1986 federal reforms.

Introduction

Federal policymakers are poised to reform the federal tax code for the first time since 1986. Both President Trump and House Republicans have released tax reform proposals. Each plan would make numerous changes to federal taxes for both individuals and corporations.

Federal tax reform, however, does not just impact the federal government and its revenue collections; state revenues are also affected by tax reform. States largely use the federal Internal Revenue Code as the basis of their state taxes. Changes to definitions of income, through base broadening, would flow downward to state-level taxes, impacting state revenues. In general, states should expect to see an increase in revenue from federal tax reform efforts, but in the few cases where revenue changes could result in lower revenues, state policymakers have a number of policy options available to them to ease the transition to a new tax structure.

The Need for Federal Tax Reform

Comprehensive tax reform last occurred at the federal level in 1986. Since that time, the United States tax system has become uncompetitive internationally. The federal income tax imposes high marginal rates on both businesses and individuals. The marginal corporate income tax rate is one of the highest in the world.[1] Individuals also face high marginal income tax rates. The top marginal tax rateThe marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. on labor in the United States, 48.6 percent, is higher than the average among industrialized nations, 46.3 percent.[2]

In addition to the high marginal rates, both the individual and corporate income tax bases at the federal level are in need of revision. On the individual side, several items are currently exempt that should be taxed, such as the amount paid for state and local taxes. On the corporate side, corporate income is subject to double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income. , a poor cost-recovery structure, and a worldwide tax system.

Both systems are immensely complex. Individuals spent 8.9 billion hours complying with Internal Revenue Code tax filing requirements in 2016. Total tax compliance cost the United States economy $409 billion in 2016.[3] It is against this backdrop that both the House Republicans and President Trump have proposed comprehensive tax reforms.

Overview of Proposed Federal Tax Changes

Currently, there are two major proposals to reform the federal tax code. The first plan was introduced by House Republican leadership in June 2016, called the “Better Way” proposal (also known as the “GOP Blueprint”).[4] The second plan was put forth by then-candidate Donald Trump during his presidential campaign.

Neither plan has been put into legislative language, but the frameworks that both the president and congressional Republicans outlined were detailed enough to model their impacts on federal revenues and the economy. As such, the current proposals give a good indication of what tax reform will most likely look like.

The plans are similar in many ways. Both would reduce marginal tax rates faced by individuals and businesses while broadening the federal tax base. Both plans also reduce federal revenue but grow the economy in the long run.

There are, however, many important differences in the plans. Most notably, these plans differ substantially in how they will impact the tax base, and consequently how individuals and businesses calculate their taxable income.

Changes to the Individual Income Tax

Tax Brackets and Rates

Both plans would consolidate the current seven tax bracketsA tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. into three, with rates of 12 percent, 25 percent, and 33 percent. The House GOP’s tax plan would keep the same bracket widths as current law and simply replace old rates with new rates. The 10 percent bracket and the 15 percent bracket would be replaced with a 12 percent bracket. The 25 and the 28 percent brackets would be replaced with a 25 percent bracket. A 33 percent bracket would replace the 33, 35, and 39.6 percent brackets.

President Trump’s plan proposes much the same, but the 25 percent bracket would be narrower than it is under the GOP proposal. In addition, President Trump’s tax plan would eliminate the head of household filing status.

| Current Law | Trump | House GOP | Single Brackets | Married Brackets | Head of Household (n/a for Trump Proposal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | 12% | 12% | $0 to $9,275 | $0 to $18,550 | $0 to $13,250 |

| 15% | 12% | 12% | $9,275 to $37,650 | $18,550 to $75,300 | $13,250 to $50,400 |

| 25% | 25% | 25% | $37,650 to $91,150 | $75,300 to $151,900 | $50,400 to $130,150 |

| 28% | 25% | 25% | $91,150 to $112,500 | $151,900 to $225,000 | $130,150 to $168,750 |

| 28% | 33% | 25% | $112,500 to $190,150 | $225,000 to $231,450 | $168,750 to $210,800 |

| 33% | 33% | 33% | $190,150 to $413,350 | $231,450 to $413,350 | $210,800 to $413,350 |

| 35% | 33% | 33% | $413,350 to $415,050 | $413,350 to $466,950 | $413,350 to $441,000 |

| 39.6% | 33% | 33% | $415,050+ | $466,950+ | $441,000+ |

Standard Deduction and Personal Exemption

Both proposals would alter the standard deductionThe standard deduction reduces a taxpayer’s taxable income by a set amount determined by the government. Taxpayers who take the standard deduction cannot also itemize their deductions; it serves as an alternative. and personal exemption. Under the GOP Blueprint, the standard deduction would nearly double from the current $6,300 for singles ($12,600 married filing jointly) to $12,000 for singles ($24,000 married filing jointly). The standard deduction for heads of household would also nearly double, from $9,300 to $18,000. The proposal would also convert the personal exemption into a $500 credit for dependents. Tax filers (and their spouses) would not benefit from the credit, but each of their dependents would net them a $500 nonrefundable credit.

President Trump’s proposal would increase the standard deduction to $15,000 for single filers and $30,000 for joint filers (head of household status is repealed). The Trump plan also proposes eliminating the personal exemption.

| Standard Deduction | Personal Exemption | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single | Joint | HoH | ||

| Current Law | $6,300 | $12,600 | $9,300 | $4,000 |

| Trump | $15,000 | $30,000 | Repealed | Repealed |

| House GOP | $12,000 | $24,000 | $18,000 | $500 Credit |

The Alternative Minimum Tax and Investment Income

The House GOP and Trump plans both propose repealing the Alternative Minimum Tax.

President Trump’s tax plan leaves the current rate structure applied to capital gains and dividends. The top rate would remain 20 percent. Interest income would still be taxed as ordinary income, which would face a top rate of 33 percent.

The GOP Blueprint would tax capital gains, dividends, and interest income all as ordinary income. However, individuals would be allowed to deduct 50 percent of their investment income against their taxable income.[5] As such, the top marginal tax rate for investment income would effectively be half the statutory tax rate, or 16.5 percent.

Itemized Deductions

Both plans would also limit itemized deductions. However, the GOP proposal would limit them to a much greater degree than President Trump’s proposal.

The GOP plan proposes to eliminate all itemized deductions except for the home mortgage interest deduction and the charitable contributions deduction. Eliminated deductions include medical and dental expenses, casualty and theft losses, job expenses, and other miscellaneous expenses. The largest of the eliminated deductions is the deduction for state income, sales, property, and real estate taxes. About 78 percent of the value of the eliminated itemized deductions would be from the elimination of the deduction for state and local taxes.

President Trump’s plan, rather than eliminating any itemized deductions, proposes to cap them. Under Trump’s proposal, individuals would only be able to deduct up to $100,000 in itemized deductions ($200,000 for married couples filing jointly). For example, if an individual under current law deducts $150,000 in itemized deductions, $50,000 would be added back to their taxable income under this proposal.

New Child Tax Benefits

President Trump’s plan also proposes a new benefit for families with childcare expenses. This proposal would allow taxpayers to exclude from AGI the amount they pay in childcare expenses, subject to a cap for high-income taxpayers. In addition, low-income taxpayers who would not receive a benefit from the AGI exclusion would receive an enhancement to their Earned Income Tax Credit.

This proposal is not included in the House GOP’s Blueprint. Instead, their child-related benefits are in the form of the new $500 nonrefundable credit for each dependent.

Changes to the Business Taxes

Both plans would significantly reduce marginal tax rates on businesses—both traditional C corporations and what are called “pass-through businesses.” President Trump’s tax plan would cut the corporate tax rate paired with a few changes to the way corporations are taxed. The House GOP’s proposal would convert the corporate income tax into what is called a “destination-based cash-flow tax.” President Trump’s and the House GOP plan would change the way pass-through businesses are taxed in the United States.

Trump’s Corporate Tax Cut

President Trump’s plan would reduce the current corporate income tax rate, from 35 percent to 15 percent. At the same time, the plan would eliminate the corporate alternative minimum tax.

In addition to the rate cut, President Trump’s tax plan would modestly pare back corporate tax expenditures by eliminating provisions such as the “Section 199” manufacturer deduction and various tax credits for specific activities. However, it is unclear which credits and deductions his plan would eliminate.

Lastly, his proposal would allow companies to choose between deducting net interest expense or the full deduction of capital investments, such as machinery, factories, or inventories.

It is unclear whether President Trump’s proposal would leave the current system for taxing foreign profits of U.S. multinationals in place,[6] or if his plan would reform it in some way. However, his plan would enact a one-time tax on offshore earnings at 10 percent.

The House GOP’s Destination-Based Cash-Flow Tax

The House GOP’s Blueprint would convert the current corporate income tax to what is called “destination-based cash-flow tax” (DBCFT), levied at a rate of 20 percent. Rather than taxing corporations based on where they produce their goods as under current law, corporations would be taxed based on where they sell their products. The new tax would be different than current law in four important ways:

- Full expensingFull expensing allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of certain investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings. It alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. of capital investments: This proposal would allow companies to write off or deduct the full cost of capital investments in the year in which they purchased them. This includes purchase of buildings, factories, plants and equipment, and inventories. Under current law, businesses need to depreciate, or deduct these assets over time, or use accounting procedures such as LIFO (Last-In, First-Out) or FIFO (First-In, First-Out).

- Elimination of the deduction for net interest expense: This proposal would no longer allow businesses to deduct interest expense (net of interest income).

- No residual tax on foreign profits: Under current law U.S. corporations are subject to tax on their worldwide income. However, profits earned overseas are not taxed until they are brought back to the United States and face the full U.S. tax minus what those profits faced in foreign countries. This proposal would remove this residual tax on foreign profits.[7]

- Border adjustment: The border adjustment would disallow the deduction for import purchases and exempt revenue from export sales. This would switch the tax to a destination-based tax system, which would tax companies based on the location of their sales.

Pass-through Businesses in Both Plans

Both plans also propose to change the tax treatment of pass-through businesses. Under the current U.S. tax code, several types of businesses are not subject to the corporate income tax. Instead of paying taxes on the business level, these companies pass their income through to their owners. The business owners are then required to report the business income on their personal tax returns, so that the business income is taxed under the individual income tax. These businesses are sole proprietorships, LLCs, partnerships, and S Corporations.

Both plans would place a cap on the marginal tax rate faced by individuals with pass-through businessA pass-through business is a sole proprietorship, partnership, or S corporation that is not subject to the corporate income tax; instead, this business reports its income on the individual income tax returns of the owners and is taxed at individual income tax rates. income. Trump’s plan would cap the rate at 15 percent and the House GOP plan would cap this rate at 25 percent. As such, there would be a new rate differential between wages and business income.

During the campaign, Trump’s advisors also suggested that their plan would have other requirements attached to its pass-through business proposal. It floated the idea that pass-through businesses need to retain some portion of their profits to benefit from this lower rate and would may need to pay an additional tax on the profits when distributed to the owners. However, details of the proposal are still unclear.

Other Changes

Both plans would eliminate the federal estate and gift taxes.

Impacts to the Federal Budget and the Economy

The two proposed tax plans would significantly change the way the U.S. federal tax code raises revenue, and how much it would raise. Both plans would reduce the amount of revenue that the federal government would raise over the next decade. The Trump proposal, which greatly reduces marginal rates but does not substantially broaden the tax base, would reduce revenue by $5.9 trillion over the next decade, or about 14 percent of federal revenue. The House GOP proposal, like the Trump plan, would reduce marginal rates, but features a greater commitment to the idea of base broadeningBase broadening is the expansion of the amount of economic activity subject to tax, usually by eliminating exemptions, exclusions, deductions, credits, and other preferences. Narrow tax bases are non-neutral, favoring one product or industry over another, and can undermine revenue stability. . As such, the plan does not reduce federal revenue by nearly as much. We estimate that it would reduce revenue by $2.4 trillion over the same period, representing about 6 percent of federal revenue. It is also worth noting that annual losses relative to current law would decrease over time under the GOP Blueprint. This is due to transition effects, with many of the changes associated with the cash-flow tax resulting in more lost revenue in the first few years than in the out years.

Both plans would reduce marginal tax rates on work, saving, and investment. Consequently, both plans would result in a larger economy in the long run. The House GOP plan would increase the level of long-run GDP by 9.1 percent[8] and the Trump administration’s tax plan would increase the level of GDP by 8.2 percent.[9]

| Trump | House GOP | |

|---|---|---|

| Source: Tax Foundation Taxes and Growth Model, March 2016 | ||

| GDP (change in level) | 8.2% | 9.1% |

| Wage Rate (change in level) | 6.3% | 7.7% |

| Full-time Equivalent Jobs (in thousands) | 2,155 | 1,687 |

| Static Revenue Impact (in billions, over 10 years) | -$5,906 | -$2,418 |

| Static Revenue Impact (percent, over 10 years) | -14% | -6% |

Impact to State Budgets

Federal tax policy, like federal spending policy, impacts states, as state tax codes are intertwined with the federal tax code in a number of ways. States use federal definitions of income and federal procedures and regulations to manage their own tax codes. Comprehensive tax reform at the federal level would influence state revenues and tax structures.

Conformity

The key to understanding how federal tax reform would change state tax codes and revenues is conformity. For reasons of administrative simplicity, states frequently seek to conform many, though rarely all, elements of their state tax codes to the federal tax code. This harmonization of definitions and policies reduces compliance costs for individuals and businesses with liability in multiple states and limits the potential for double taxation of income.[10] No state conforms to the federal code in all respects, and not all provisions of the federal code make for good tax policy, but greater conformity substantially reduces tax complexity and has significant value.

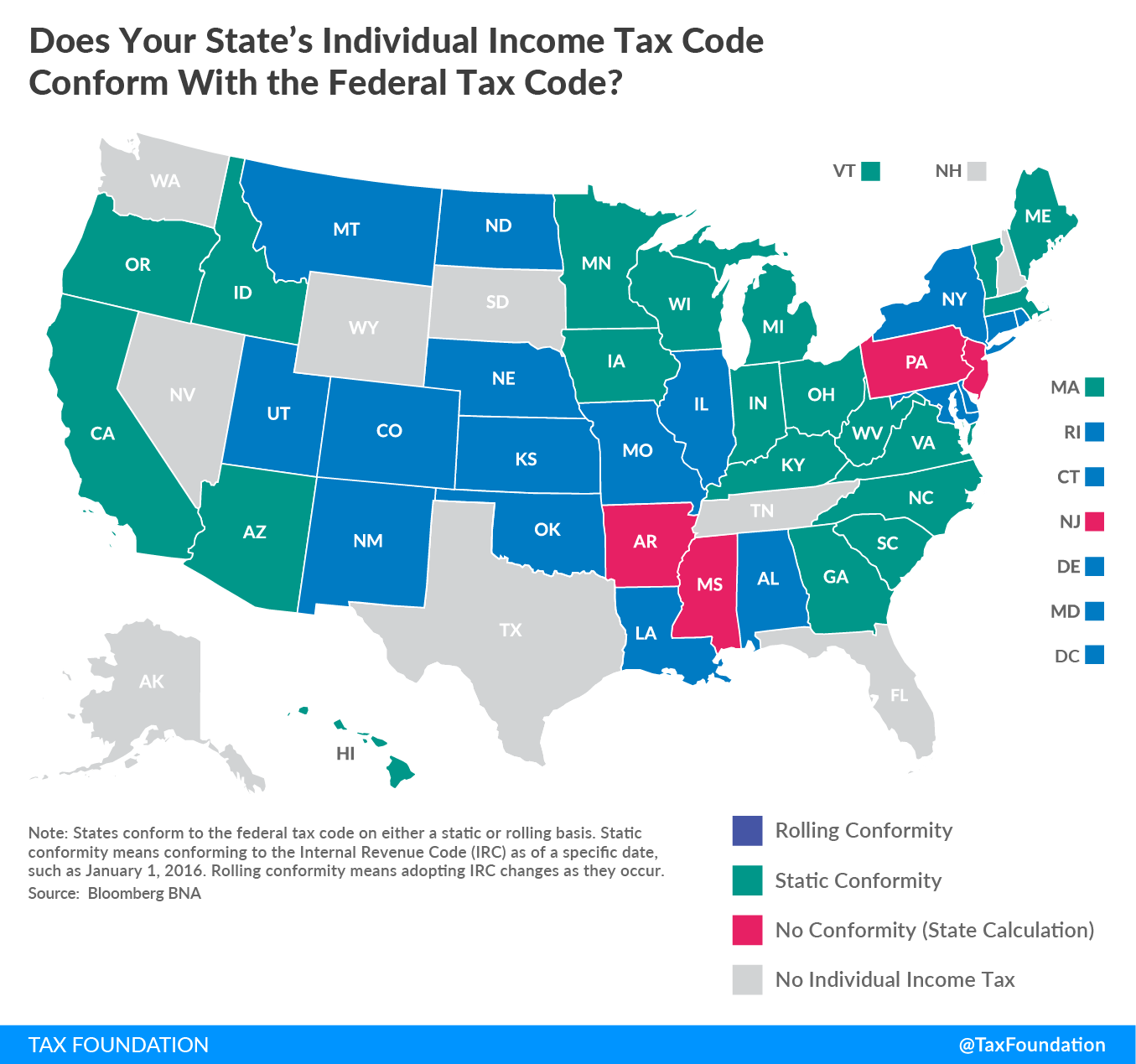

States conform on either a static or rolling basis. Static conformity means conforming to the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) as of a specific date, such as January 1, 2016. Rolling conformity means adopting IRC changes as they occur. The states are roughly split between these two types of conformity. Twenty states have rolling conformity, while 18 states have static conformity. (The remaining states do not tax individual income or use their own calculation of income.) But among the states with static conformity, the dates of conformity vary widely. Massachusetts conformed to the IRC as of 2005, while many other states have conformed as of 2016 (see Appendix A).

Individual Income Taxes

The first large area of conformity is federal definitions of income. Twenty-seven states begin with federal adjusted gross income (AGI) as their income tax base. Six states use federal taxable income and three states use federal gross income as their starting point (see map below).

Even if a state uses federal AGI as its starting calculation, there can be adjustments (e.g., pension and retirement income, Social Security benefits, and federal deductibility) which diverge from the federal treatment of income.[11] Twelve states conform to the federal standard deduction, while 10 use the federal personal exemption.[12] Appendix A of this paper provides a full list for each state.

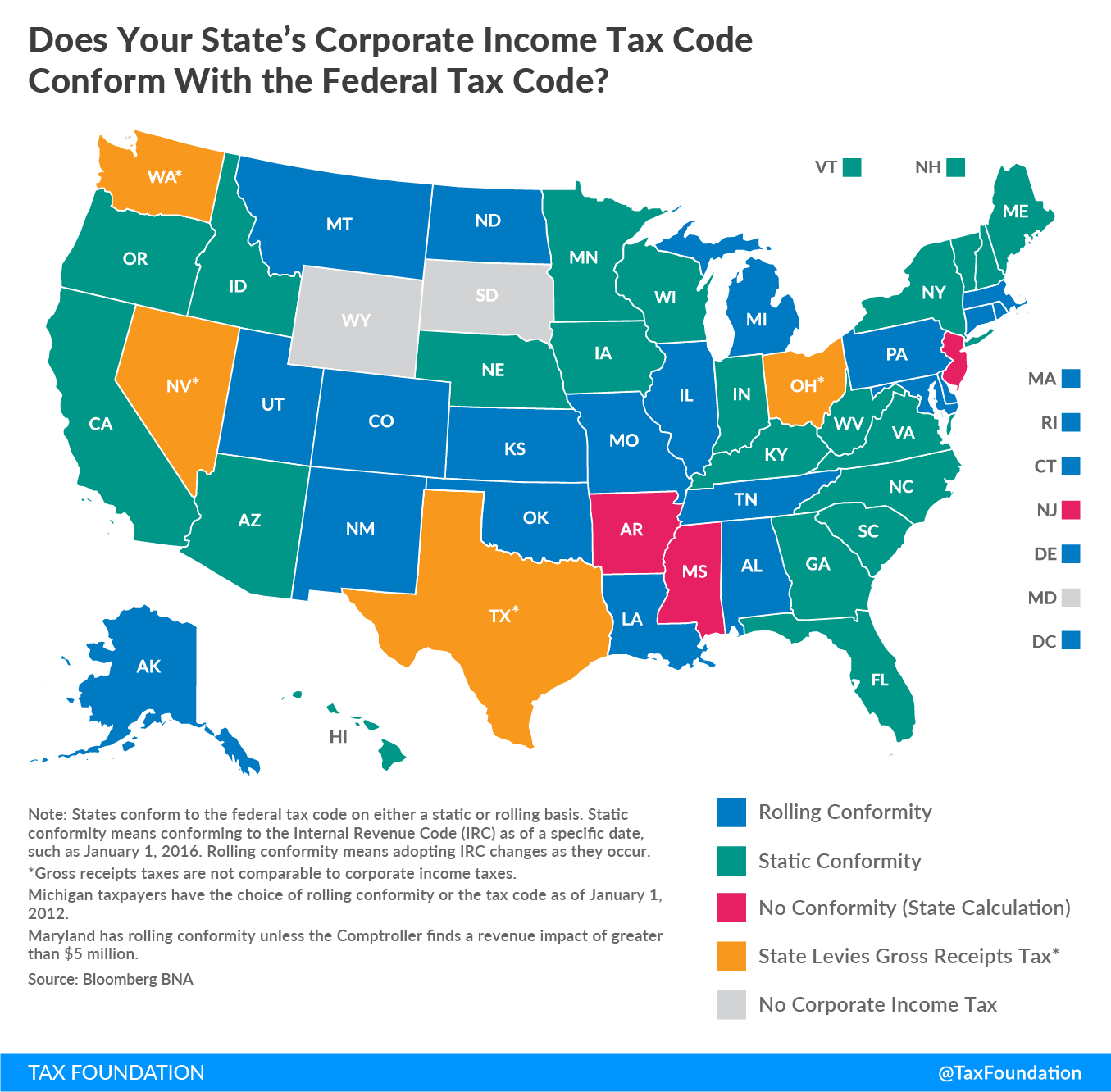

Corporate Income Taxes

States also conform to the IRC for corporate income tax calculations. States tend to conform to either taxable income before net operating losses or taxable income after net operating losses. Forty-one states conform to one of these two definitions of income. Two states have their own calculation of income, and the remaining states either do not tax corporate income or impose a statewide gross receipts tax (see map below).

As with individual income taxes, states then also can adjust the base level of income. For instance, many states do not conform on the length of time that net operating losses can be carried forward or backward, but the majority of states do conform to federal Section 179 bonus depreciation schedules. (Appendix B provides for a full list.)

Tax Change Provisions of Interest for States

Multiple provisions within the GOP Blueprint and the Trump tax plans would impact state budgets, and how a state conforms to the federal code impacts state-specific revenue projections. For instance, a state that uses federal taxable income or AGI as its starting point would likely see an increase in revenue due to the elimination of most federal itemized deductions. Under the Trump and GOP tax plans, the federal tax base (the definition of taxable income) would become much broader, leading to an expansion of the state tax base. The federal changes include rate cuts to offset the broader bases, but states set their tax rates independently. Absent state-level changes, states would have a much larger tax base without correspondingly lower rates, leading to higher state-level revenue.

As mentioned previously, some states couple with the federal code on the size of the standard deduction. Both the Trump plan and the GOP Blueprint would expand the standard deduction, meaning the state standard deductions would increase in tandem, decreasing state revenues. On the other hand, the elimination of the interest deduction at the federal level would increase revenues at the state level.

Though the change would not have a direct financial cost to state budgets, the elimination of the state-local taxes paid deduction would force high-income filers, particularly in states like New York and California, to feel the full effect of their states’ high marginal rates. The current federal deduction diminishes the effects of high state rates.[13]

Similarly, the repeal of the federal estate taxAn estate tax is imposed on the net value of an individual’s taxable estate, after any exclusions or credits, at the time of death. The tax is paid by the estate itself before assets are distributed to heirs. could increase the cost of tax administration for states. Fourteen states and the District of Columbia have an estate tax, but states rely heavily on the Internal Revenue Service to administer their estate tax through use of federal estate tax audits and federal estate tax regulations and guidance. [14] If the federal government succeeds in repealing the federal estate tax, states would bear the full administrative burden of this complex tax.

Estimating the revenue impact of border adjustability would face data availability challenges. The U.S. Census Bureau reports state-level data on imports and exports by origin and destination, but even the Census suggests that its data is not the most reliable. For example, export data could be based off a “consolidation point,” while import data might be based on an intermediary or distribution center.[15] There is no easy way for states to model the flow of imports and exports in their state, making it difficult to adequately predict whether a state would see a revenue increase or decrease due to this provision.[16]

Federal 10-Year Budget Window vs. States’ 1- or 2-Year Budget Window

While the federal government has an annual budget, the wide use of the 10-year budget projection window to evaluate legislation and the ability to deficit spend will ease transition costs for the federal government. As discussed, the GOP Blueprint eliminates depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment. schedules and goes to immediate, first-year expensing.[17] Full expensing is a front-loaded cost, but it smooths out over the 10-year federal budget window. The elimination of the deduction for net interest expenses, however, would move in the opposite direction. It would raise state (and federal) revenues, with the amount raised growing every year. The federal government has the fiscal flexibility to handle this, as the federal government has the ability to run deficits, and federal budgeting is traditionally done over a 10-year window.

State budgeting, however, does not permit the same flexibility. States budget in one- or two-year cycles, and 49 states have constitutional or statutory balanced budget requirements.[18] States do not have the ability to run a deficit in the short term to offset a long-term tax change. Absent federal transition assistance, states facing a negative revenue change as a result of the federal changes would therefore need to respond quickly to any revenue gains or losses from federal tax reform efforts.

State Revenues Likely Grow Under Proposed Tax Reforms

Given the current structures of the GOP Blueprint and the Trump tax plan, it is likely that most states would see increases in revenue. The base expansion under the individual income tax reform, as envisioned under these two plans, is quite large, meaning that states that use the IRC as their tax base would see an increase in revenue from the expanded base. The federal government offsets the increase in revenue with lowered and consolidated rates, but states set their rates independently. Without state action on marginal tax rates, states would see a large and rapid increase in revenues.

It is possible, however, that states would lose revenue from the corporate income tax changes, at least in the short term. Full expensing would shift state revenues later in time, resulting in a revenue reduction particularly in the first several years. However, the elimination of the deduction for net interest would offset part of that by increasing state revenues. However, even for the states that see a loss of revenue from the corporate income tax changes, the revenue from individual income tax changes would be of a much larger magnitude.

The revenue changes for states due to the border adjustment are less straightforward, as it varies by the industry mix and concentration of importers or exporters in a state. On net, state revenues should increase from the border adjustment.

Lessons from the 1986 and 2002 Federal Tax Changes

The experience of the 1986 federal reforms provides insight into just how this dynamic plays out for states.[19] As federal reform progressed, the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO) and the now-defunct Advisory Committee on Intergovernmental Relations (ACIR) projected income tax revenue impacts for each of the 50 states. On average, NASBO estimated that state revenues would increase by 8.3 percent, but there was large variation. Connecticut’s revenue would increase by 48.1 percent, while Vermont would lose 9.3 percent of its revenue.[20] ACIR found similar overall results, though it differed with NASBO on a few results. Estimates for 15 states differed by more than 3 percentage points.[21]

States responded in a number of ways. Ohio, for instance, acted quickly to cut its state-level tax rates to return its new revenue back to taxpayers.[22] Other states decided to expand their standard deductions and personal exemptions with the new state revenue. Nine states, including Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, and Utah, decided to retain the higher level of revenue in their budgets.[23]

Finally, several states decided to use the federal reforms as the impetus for state-level tax reform. Minnesota and New York passed robust tax reform packages that “simplified their income taxes by repealing numerous deductions and credits, by reducing the number of tax rates from 16 in Minnesota and 12 in New York to two, and by eliminating taxes on the poor.”[24]

Overall, states tended to mirror the federal reforms. States broadened their tax bases, lowered rates, simplified their tax codes, and increased progressivity. Federal tax reform was a strong impetus for states on their own to pass a number of tax reforms.

But states do not always decide to conform to federal tax changes, especially if a revenue loss is projected. In 2002, Congress accelerated depreciation rules. By allowing firms to depreciate assets faster, federal and state revenues fell. States were not anxious to adopt these changes and lose revenue, particularly during an economic downturn which was already stretching state budgets. Within one year of federal adoption, 29 states had limited the impact of, or decoupled entirely from, this provision.[25]

Possible Options for States

While federal tax reform would likely increase revenues for states and their budgets, the exact timing of those changes could present challenges to states.

For the few states that might see decreases in revenue from federal tax reform, there are several options to ameliorate any possible revenue decreases caused by timing issues created by the federal government.

Phase-In

States could phase in reforms, using tax triggers and phase-ins, which are already popular tools at the state level. Phase-ins specify how a state plans to slowly implement reforms, while moving towards the end goal of total conformity with the federal code.

Revenue Triggers

Tax triggers are a similar mechanism, but require revenue targets to be hit before changes occur. This would be particularly helpful for states in the initial post-tax-reform period.

Contingent Enactment

States could also include contingent enactment clauses, where detailed reforms are outlined but predicated on an event occurring, such as federal tax reform. States would proactively detail how they plan to modify their tax code when federal tax reform happens.

Special Sessions

States could also call special sessions later in the year. For instance, most states start their fiscal years on July 1, while taxes are collected on a calendar year basis. States must adopt their budgets by late June for the upcoming annual or biennial budget. It is highly unlikely that federal tax reform will be passed before states adopt their fiscal year 2018 budgets. States would need to budget without adding the increased revenues from federal tax reform to their budgeting baselines. Thus, states could call special sessions to handle the process of adding the new revenues to their baseline and determining what to do with the additional money.

Concurrent Reform

Federal tax reform presents an opportunity for states to consider ways to improve their own tax structures, as was the case with the 1986 federal reforms. States typically have tax expenditures in excess of the federal expenditures. States could look at removing their unique credits and deductions, under both the individual and corporate income taxes, to generate any necessary revenue to close revenue gaps caused by transitioning to the new tax systems.

Conclusion

The federal government could pass comprehensive tax reform for the first time since 1986. However, any federal-level tax change would impact state budgets, as most states tie their individual and corporate income tax codes to the federal tax code.

Historically, states have tended to mirror federal tax changes in their own codes. However, this trend is less robust when large revenue losses are associated with coupling. Most states would likely experience a revenue increase under the federal plans currently under consideration. Still, state policymakers should be aware of the numerous options available to them for responding to federal tax reform. The passage of federal tax reform provides an opportunity for state policymakers to revisit, review, and reform their state tax codes.

[1] Kyle Pomerleau and Emily Potosky, “Corporate Income Tax Rates around the World, 2016,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 525, August 18, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/corporate-income-tax-rates-around-world-2016/.

[2] Scott Greenberg, Income Taxes Illustrated, Tax Foundation, November 3, 2015, https://taxfoundation.org/income-taxes-illustrated/.

[3] Scott A. Hodge, “The Compliance Costs of IRS Regulations,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 512, June 15, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/compliance-costs-irs-regulations/.

[4] House GOP Conference, “A Better Way, Our Vision for a Confident America: Tax,” June 24, 2016, http://abetterway.speaker.gov/_assets/pdf/ABetterWay-Tax-PolicyPaper.pdf.

[5] This is distinct from an exclusion from AGI. An exclusion from AGI would interact with other tax provisions that are based on AGI, such as the Child Tax CreditA tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. . As a deduction, there are no such interactions with these provisions.

[6] Under current law, U.S. corporations are subject to the U.S. corporate income tax on their worldwide profits. If a company earns profits in a foreign country, those profits are first subject to tax in that foreign jurisdiction. Then, when those profits are returned, or repatriated, to the United States, they are subject to the U.S. corporate income tax minus a “foreign tax credit” for income taxes already paid to the foreign jurisdiction on that income.

[7] As a transition, old untaxed profits would be taxed one time at two rates: 8.75 percent on cash assets and 3.25 percent on non-cash assets.

[8] Kyle Pomerleau, “Details and Analysis of the 2016 House Republican Tax Reform Plan,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact No. 516, July 5, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/details-and-analysis-2016-house-republican-tax-reform-plan/.

[9] Alan Cole, “Details and Analysis of the Donald Trump Tax Reform Plan, September 2016,” Tax Foundation Tax Policy Blog, September 15, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/details-donald-trump-tax-reform-plan-september-2016/.

[10] Ruth Mason, “Delegating Up: State Conformity with the Federal Tax Base,” 7 Duke Law Journal 62 (April 2013): 1269–1270.

[11] Rick Olin, “Individual Income Tax Provisions in the States,” Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau, July 2012, https://www.wmc.org/wp-content/uploads/LFB-paper-on-Individual-Income-Tax-Provisions-in-the-States.pdf, 26. Bloomberg BNA.

[12] These counts include those states that use federal taxable income as their starting point, as the federal standard deduction and personal exemption are by definition included in taxable income.

[13] Alan Cole, Richard Borean, and Tom VanAntwerp, “Which Places Benefit Most from State and Local Tax Deductions,” Tax Foundation Blog, March 25, 2015, https://www.taxfoundation.org/which-places-benefit-most-state-and-local-tax-deductions.

[14] Most states eliminated their state estate taxes following the phaseout of the federal estate tax pick-up credit beginning in 2001.

[15] Census Bureau, Foreign Trade Statistics: State Data Series, https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/aip/elom.html.

[16] It is also unclear if the border adjustment would be accomplished via a tax credit or a tax deduction. Its structure would mean that states would conform in different ways. A deduction would likely be conformed automatically, but a credit would require more proactive action by states.

[17] The Trump plan provides an option of full expensing or deducting net interest expenses.

[18] Vermont, the exception, balances its budget regardless.

[19] For an overview of the 1986 federal reforms, please review Scott Greenberg, John Olson, and Stephen J. Entin, “Modeling the Economic Effects of Past Tax Bills,” Tax Foundation Fiscal Fact no. 527, September 14, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/modeling-economic-effects-past-tax-bills/.

[20] These numbers reflect the change in individual income tax revenue, not total revenue, meaning that changes in total revenue would be less than these stated numbers.

[21] Steven D. Gold, “The State Government Response to Federal Income Tax Reform: Indications from States that Completed Their Work Early,” National Tax Journal 40, No. 3 (September 1987): 431-444.

[22] Ibid, 437.

[23] Ibid, 438.

[24] Ibid, 439.

[25] Jeffrey A. Friedman, “What Would Federal Tax Reform Mean for States?” Urban Institute Forum, March 31, 2016.

Share this article