Key Findings

- In Illinois, legislation is pending repealing the state constitution’s uniformity clause and adopting a graduated-rate income taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities. with a top rate higher than the current rate. Graduated-rate taxation has also emerged as a theme in the gubernatorial race.

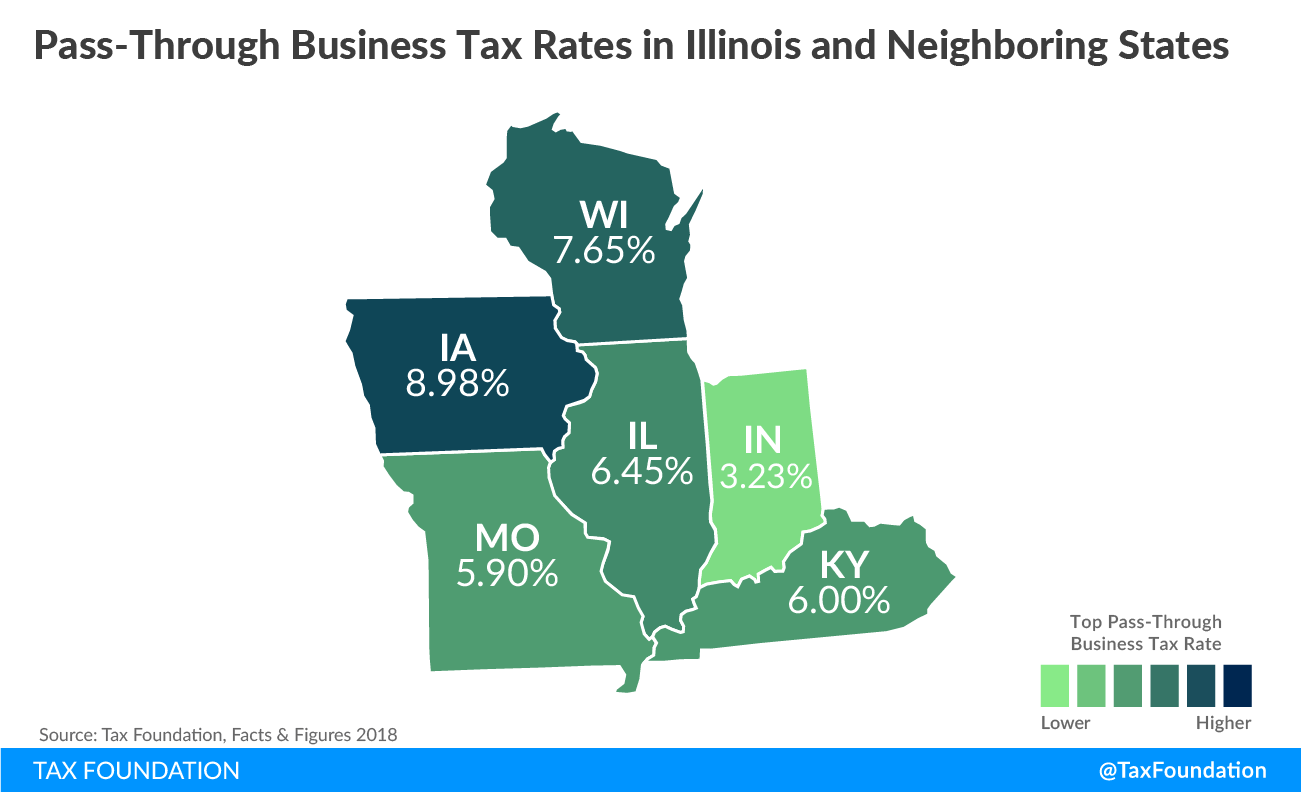

- Illinois’ low, single-rate individual income taxAn individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. is the saving grace of an otherwise high-rate and uncompetitive state tax code, and even its benefits are limited by a surtaxA surtax is an additional tax levied on top of an already existing business or individual tax and can have a flat or progressive rate structure. Surtaxes are typically enacted to fund a specific program or initiative, whereas revenue from broader-based taxes, like the individual income tax, typically cover a multitude of programs and services. on pass-through businessA pass-through business is a sole proprietorship, partnership, or S corporation that is not subject to the corporate income tax; instead, this business reports its income on the individual income tax returns of the owners and is taxed at individual income tax rates. income which brings the rate to 6.45 percent for small businesses.

- Graduated-rate income taxes are more susceptible to rate changes, a concern in a state where tax increases are contemplated so frequently. Two years ago, lawmakers came close to adopting an 11.25 percent tax on pass-through businesses.

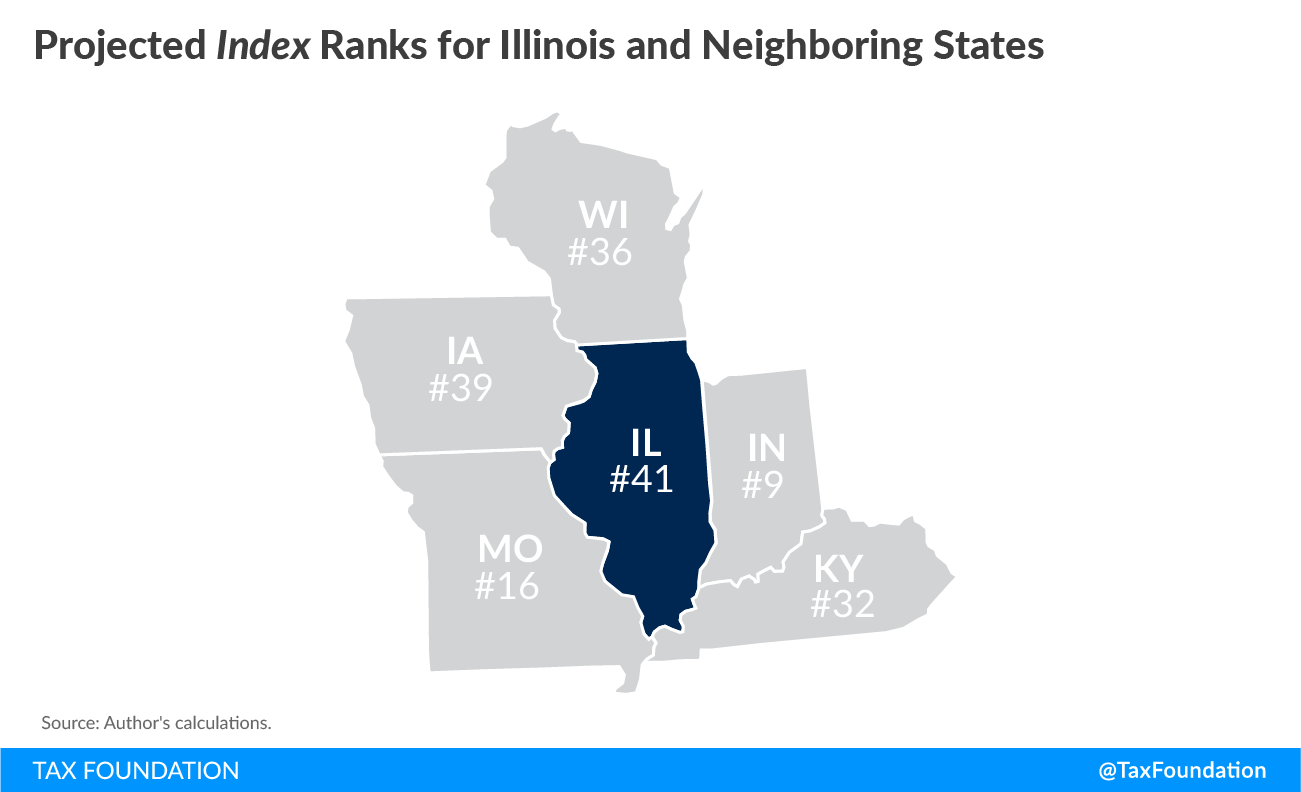

- Under House Bill 3522, Illinois would fall from 29th to 41st overall on the State Business Tax Climate Index, which measures tax structure, as the change would eliminate the state’s one competitive advantage.

- In the past, the state’s high taxes have forced officials to cut lucrative incentive deals with companies to keep them in-state. At a time when other states are increasingly working to make their own codes more competitive, repealing a taxpayer protection in the state constitution would be a step in the wrong direction.

Introduction

For small businesses in Illinois, the past few years have inspired little confidence. In 2016, the legislature came close to bringing the top rate on pass-through businesses to 11.25 percent, a rate only eclipsed in California.[1] Although that proposal was narrowly defeated, the legislature overrode a gubernatorial veto to increase the pass-through business rate from 5.25 to 6.45 percent in 2017, coupled with an increase in the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax. .[2] Now, leading contenders in the 2018 gubernatorial race are campaigning on another tax increase—and not just a tax increase, but a fundamental alteration of the Illinois system of taxation, the repeal of the state constitution’s uniformity clause.

Repealing the uniformity clause, which prohibits a graduated-rate income tax and provides other taxpayer protections, could have a dramatic impact on Illinois tax policy. It is an alteration that would exacerbate tax uncertainty, remove a barrier to tax increases in a state already held back by high taxes,[3] and make Illinois less competitive with its peers during a uniquely competitive moment, when many states are positioning themselves to attract some of the new investment enabled by federal tax reform.[4]

Background

The Illinois individual income tax is currently levied at a flat rate of 4.95 percent, to which is added a 1.5 percent “personal property replacement tax” (PPRT) on pass-through business income, yielding a 6.45 percent rate on owners of S corporations, LLCs, partnerships, and sole proprietorships, all of whom pay under the individual (not the corporate) income tax. Despite the confusing nomenclature, the PPRT is not a property taxA property tax is primarily levied on immovable property like land and buildings, as well as on tangible personal property that is movable, like vehicles and equipment. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local revenue in the U.S. and help fund schools, roads, police, and other services. but rather a second income tax, imposed on the same income base, and levied for the purpose of making local governments whole in 1979 after the abolition of tangible personal property taxes in Illinois.[5]

Until 2011, the state’s individual income tax was imposed at a 3 percent rate. That year, confronted with mounting debt and unpaid bills, Illinois legislators approved a temporary tax increase which, among other things, increased the individual income tax from 3 to 5 percent. A partial expiration was permitted to take effect in 2015, with the individual income tax rate falling back to 3.75 percent. Absent further legislative action, a subsequent reduction to 3.25 percent would have transpired in 2025.[6]

But the legislature did act, overriding a governor’s veto to hike the rate from 3.75 to 4.95 percent even though the temporary tax increase accomplished none of its aims. Despite raising an additional $30 billion during the years it was in effect, Illinois’ current backlog of unpaid bills remains higher than it was before the tax increase.[7]

Figure 1.

Governor Bruce Rauner (R) has insisted that tax rate changes be accompanied by structural reforms designed to improve the state’s finances, but the rate increase, accomplished over his opposition, was not paired with any broader changes. Still, it could have been worse: the previous year, the legislature very nearly marshaled the votes to force a tax hike which would have increased the small business rate to 11.25 percent.[8]

Graduated-Rate Income Tax Proposals

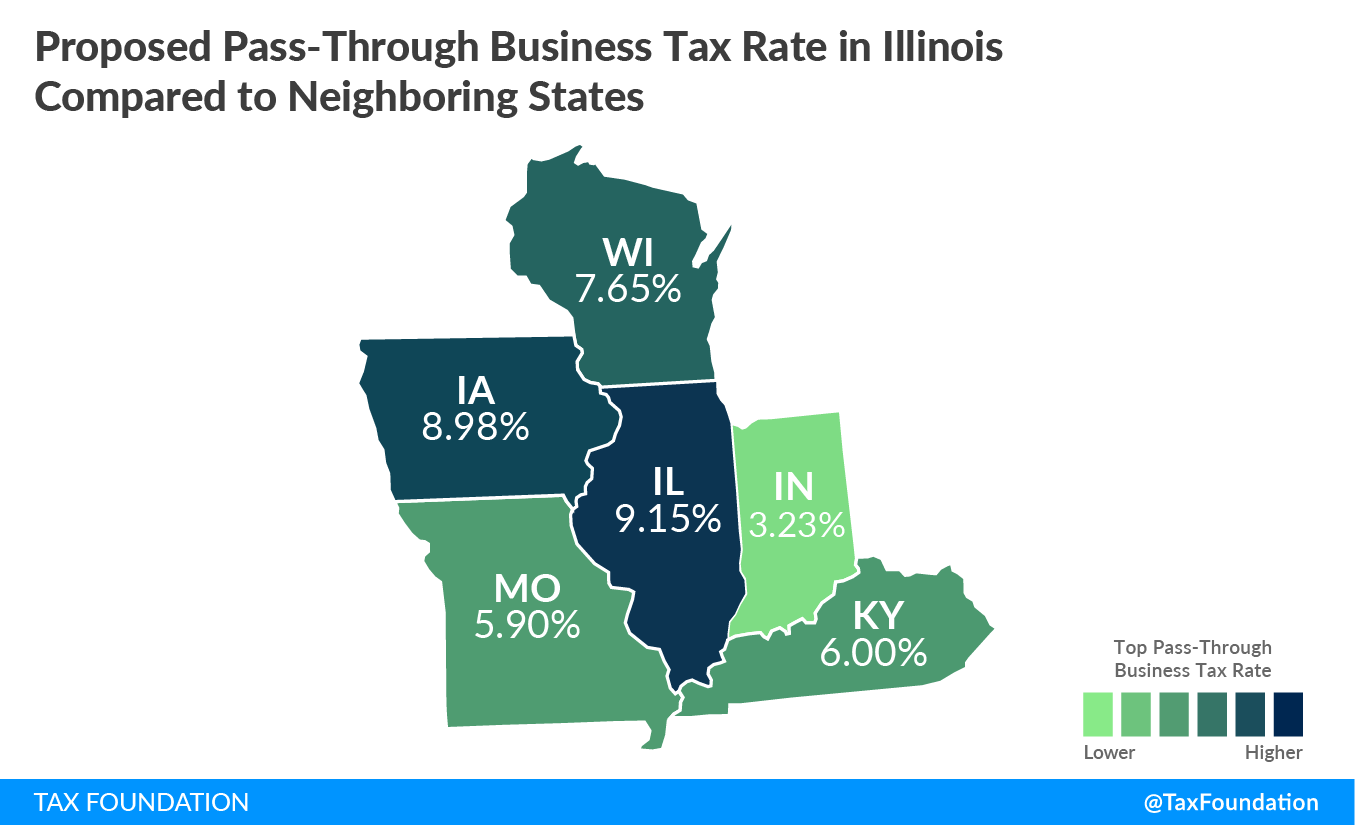

In his budget for fiscal year 2019, Governor Rauner has proposed a modest income tax reduction, trimming the rate from 4.95 to 4.7 percent,[9] while most of the candidates vying to oppose him this November favored a graduated-rate income tax with a top marginal rate higher than the current 4.95 percent.[10] Democratic nominee J.B. Pritzker,[11] along with other primary candidates including Chris Kennedy,[12] Bob Daiber,[13] and Daniel Biss,[14] all campaigned on proposals for a graduated-rate income tax, which would require a constitutional amendment. Meanwhile, Representative Robert Martwick (D) has introduced House Bill 3522 which, subject to ratification of a corresponding constitutional amendment, would create a four-bracket individual income tax with a top rate of 7.65 percent,[15] matching the rates of neighboring Wisconsin.

| Current Law | HB 3522 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income Range | Individuals | Pass-Throughs | Individuals | Pass-Throughs |

| $0 – $7,499 | 4.95% | 6.45% | 4.0% | 6.5% |

| $7,500 – $14,999 | 4.95% | 6.45% | 5.84% | 7.34% |

| $15,000 – $224,999 | 4.95% | 6.45% | 6.27% | 7.77% |

| $225,000 + | 4.95% | 6.45% | 7.65% | 9.15% |

In fact, mirroring Wisconsin is something of a theme. Biss, a state senator, has suggested “look[ing] at neighboring states like Wisconsin and Iowa,” both of which have graduated-rate income taxes, and argued that Illinois suffers in comparison with its regional peers. “All we need to do is to be as good as Ohio,”[16] he also argues. However, while Ohio has a graduated-rate income tax, its top marginal rate of 4.997 percent is almost identical with Illinois’ current flat rate even before accounting for the PPRT,[17] and well below the top marginal rates being contemplated in Illinois.

In Wisconsin, meanwhile, legislators are exploring ways to lower income tax rates,[18] and last year, the state assembly’s Republican majority even unveiled plans to move to a single-rate income tax.[19] While Illinois lawmakers seek to mirror Wisconsin’s tax code, legislators in Wisconsin are trying to move in the opposite direction.

It is certainly true that many states impose graduated-rate income taxes. It is also true, however, that Illinois already imposes uniquely high tax burdens, and a constitutional change would double down on the least competitive elements of the state’s system of taxation.

With a top marginal rate of 7.65 percent, the top rate for pass-through businesses would be 9.15 percent, higher than the rate on such businesses in any neighboring state. By way of comparison, four of Illinois’ six neighboring states impose top marginal rates of 6 percent or less on small businesses, and a fifth (Iowa, with a top rate of 8.98 percent) adopts a deduction for federal taxes paid which dramatically reduces individual income tax liability.[20] Iowa’s federal deductibility means that income subject to top marginal federal (37 percent) and state (8.98 percent with federal deductibility) rates faces an Iowa effective rate of 5.66 percent, against which the proposed rates in Illinois would compare unfavorably.[21]

Figure 2.

Furthermore, under House Bill 3522, while the top rate of 7.65 percent is reserved for filers with more than $225,000 in taxable incomeTaxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. Taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. , the vast majority of income-earners would reach the 6.27 percent rate, which kicks in at $15,000.[22] This results in an income tax increase for the overwhelming proportion of Illinois income-earners. A household with $50,000 in taxable income would see its income tax liability rise by 18 percent, while a household with $75,000 in taxable income would face a 21 percent tax increase. The new brackets would not be indexed to inflation, resulting in a phenomenon called “bracket creep,” where a greater share of residents’ income is subject to higher rates over time.

| Current Law | HB 3522 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taxable Income | Tax Liability | Effective Rate | Tax Liability | Effective Rate |

| $25,000 | $1,237.50 | 4.95% | $1,365.00 | 5.46% |

| $50,000 | $2,475.00 | 4.95% | $2,932.50 | 5.87% |

| $75,000 | $3,712.50 | 4.95% | $4,500.00 | 6.00% |

| $100,000 | $4,950 | 4.95% | $6,067.50 | 6.07% |

| $250,000 | $12,375 | 4.95% | $15,817.50 | 6.33% |

The Illinois state constitution imposes three limitations on income taxation:

- Income taxes must be imposed at a single (non-graduated) rate;

- No more than one such tax may be “imposed by the State for State purposes” on individual income, and one on corporate income; and

- The corporate income tax rate cannot exceed 160 percent of the individual income tax rate.[23]

Proponents of a graduated-rate income tax are understandably focused on the first restriction, but the other two could prove collateral damage. The last time Illinois policymakers pursued a constitutional amendment on uniformity, they opted to strike all three provisions, not just the first.[24] The personal property replacement tax avoids running afoul of the second provision because, while it is imposed by the state, it is ostensibly for local purposes and the revenues are remitted to local governments.

Consequences of Uniformity Clause Repeal and Graduated-Rate Income Taxation

Under Rep. Martwick’s plan, the top marginal rate would kick in at $225,000, while one of the gubernatorial candidates (Daiber) has proposed a top rate kicking in at $1 million. The latter, at least, is a high threshold, but 52.7 percent of pass-through business income is associated with businesses with adjusted gross incomes (AGIs) of $1 million or more. In 2016, legislative proposals included a top rate kick-in of $500,000. House Bill 3522 uses $225,000—and according to the Internal Revenue Service, 94.1 percent of all pass-through income is associated with filers reporting business income above $200,000. The table below gives a sense of how many Illinois small businesses could be adversely affected by tax increases, and the percentage of total pass-through AGI they represent.

| Note: In aggregate, businesses with less than $25,000 in AGI post negative income. Source: IRS Statistics of Income (2015) |

||||

| Number of Businesses | Adjusted Gross Income | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGI Range | Amount | % of Total | Amount | % of Total |

| $0 – $24,999 | 54,000 | 13.8% | ($731,141) | (2.8%) |

| $25,000 – $99,999 | 130,890 | 33.4% | $1,395,968 | 5.4% |

| $100,000 – $199,999 | 98,910 | 25.3% | $2,253,168 | 8.7% |

| $200,000 – $499,999 | 70,600 | 18.0% | $5,166,439 | 19.8% |

| $500,000 – $999,999 | 21,940 | 5.6% | $5,000,858 | 19.2% |

| $1,000,000 + | 15,040 | 3.8% | $12,954,341 | 49.7% |

Given the frequency with which lawmakers have looked to income tax increases in lieu of broader reforms, coupled with the fact that a tax with a top rate of 11.25 percent on small businesses came within a hair’s breadth of securing the support of a legislative supermajority, individuals and small business owners have good cause for concern that any tax increases adopted in the next year or two will not be the last.

This is important because graduated-rate income tax systems can make future rate increases easier. When most or all taxpayers share in a tax increase, there is substantial political pressure to balance revenue needs with tax competitiveness. The ability to single out select taxpayers for higher rates—which will also fall on many small businesses—would make future tax increases easier in a state where lawmakers have already demonstrated a willingness to countenance unusually high rates. Double-digit rates on pass-through businesses were seriously contemplated as recently as two years ago. Such rates would be unthinkable in a single-rate system, but could easily reemerge if the uniformity clause were repealed.

High taxes on income are generally among the least desirable taxes because they discourage wealth creation. A comprehensive review of international econometric tax studies found that individual income taxes are among the most detrimental to economic growth, outstripped only by corporate income taxes.[25] The literature on graduated-rate income taxes is particularly unfavorable, with substantial evidence that higher marginal tax rates reduce gross state product growth even after adjusting for overall state tax burdens.[26]

Were the legislature to adopt something similar to House Bill 3522, with a top marginal rate of 7.65 percent (and 9.15 percent on pass-through businesses), Illinois would slip from 29th to 41st overall on the State Business Tax Climate Index, which measures tax structure. On the individual income tax subcomponent of the Index, Illinois would slide from 16th to 32nd. Under the Daiber plan, making the generous assumption that brackets are indexed for inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power. , Illinois would fall to 39th overall.

The state’s relatively low single-rate individual income tax has historically been one of the few saving graces in a state with otherwise high and economically inefficient taxes. The state ranks below average on four of the Index’s five subcomponents (corporate income, sales, property, and unemployment insurance taxes), achieving a competitive ranking in only one area: individual income taxes. Eliminating that single advantage would strike a serious blow to the state’s competitiveness.

| Overall Rank | Income Tax Component Rank | |

|---|---|---|

| Current Law | 29th | 16th |

| House Bill 3522 | 41st | 32nd |

| Daiber Plan with Inflation Indexing | 39th | 28th |

The adverse impact of any such tax increase on the state’s small businesses, which employ nearly half of the state’s workforce,[27] would harm many working Illinoisans even if they would personally receive a reduction in their individual income tax liability.

Repealing the uniformity clause could change corporate taxation as well. Not only would it enable a graduated-rate corporate income tax, a concept that has very little intellectual justification,[28] but it would also sever the existing linkage between the individual and corporate income taxes. Including a 2.5 percent PPRT on corporate income, the state’s corporate income tax already stands at 9.5 percent, behind only Iowa (12 percent), Pennsylvania (9.99 percent), and Minnesota (9.8 percent).[29] There is little room to drive it higher without doing serious damage to the state’s economy.

Figure 3.

Conclusion

Illinois has already earned a well-deserved reputation as a high-tax state and has paid the price for it. After the imposition of 2011’s temporary tax increases, the state had to cut lucrative incentive deals with high-profile companies like Sears and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange to keep them from leaving the state.[30] Other states in the region, like Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin, have improved the competitiveness of their tax codes in recent years, and Iowa lawmakers have made tax reform a priority this year.

Ohio, cited as an important peer state by at least one proponent of graduated-rate income taxes, has a top marginal individual income tax rate of 4.997 percent, which compares favorably to the 6.45 percent rate Illinois already imposes on pass-through businesses. Ohio also forgoes a corporate income tax, although it does impose a low-rate but nonneutral gross receipts taxGross receipts taxes are applied to a company’s gross sales, without deductions for a firm’s business expenses, like compensation, costs of goods sold, and overhead costs. Unlike a sales tax, a gross receipts tax is assessed on businesses and applies to transactions at every stage of the production process, leading to tax pyramiding. in its stead.[31]

Amending the Illinois constitution and adopting a graduated-rate income tax cannot solve the state’s fundamental problems. Instead, it doubles down on an already uncompetitive tax code. Rather than addressing the income tax once and for all, it opens the door to more battles over rates in the future. Although most of these proposals are still vaguely defined, they have the potential to dramatically increase burdens on the state’s job creators and hold Illinois back at a time when other states are laboring to make their tax codes more competitive. Repealing a taxpayer protection embedded in the state constitution would be a step in the wrong direction.

[1] Jared Walczak and Joseph Bishop-Henchman, “Illinois Considers an 11.25 Percent Tax on Small Businesses,” Tax Foundation, April 26, 2016, https://taxfoundation.org/illinois-considers-1125-percent-tax-small-businesses/.

[2] Monique Garcia and Kim Geiger, “Illinois Senate Votes to Override Rauner Veto of Income Tax Hike, Budget,” Chicago Tribune, July 4, 2017, http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/local/politics/ct-illinois-senate-income-tax-hike-budget-met-0705-20170704-story.html.

[3] According to U.S. Census data, Illinois tax collections were the 12th highest per capita in fiscal year 2015, after the temporary tax increases had expired and before the new tax hikes went into effect. See U.S. Census Bureau, “2015 State and Local Government Finance,” https://www.census.gov/govs/local/.

[4] The merits and demerits of federal tax changes are outside the scope of this paper, but several reforms promote greater domestic investment. A lower corporate rate reduces the incentive to locate operations abroad and, by decreasing costs, increases the number of potential investments that are economically viable at any given time. A provision called “full expensingFull expensing allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of certain investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings. It alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs. ” also reduces some of the prior tax code’s built-in disincentives for capital investment. For a broader analysis of the economic implications of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, see Tax Foundation, “Preliminary Details and Analysis of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Dec. 18, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/final-tax-cuts-and-jobs-act-details-analysis/.

[5] Illinois Department of Revenue, “Personal Property Replacement Tax,” http://tax.illinois.gov/localgovernment/overview/howdisbursed/replacement.htm.

[6] 35 Ill. Comp. Stat. § 5/201.

[7] The current backlog stands at $9.2 billion, after spiking to nearly $16.7 billion in late 2017 when bond payments could not be made for two years due to the lack of a state budget. The backlog stood at $7.9 billion before the temporary tax increases took effect. See State of Illinois Comptroller, “Debt Transparency Report Summary No. 2,” Jan. 31, 2018, https://ledger.illinoiscomptroller.gov/ledger/assets/file/DTA/current/DTAReport.pdf; and State of Illinois Comptroller, “The Ledger: Debt Transparency Report,” http://ledger.illinoiscomptroller.gov/.

[8] 99th Ill. Gen. Assem., House Bill 689, 2016 Sess.

[9] Greg Hinz, “Rauner’s Plan: Trim Income Tax, Push Costs to Local Governments,” Crain’s Chicago Business, Feb. 14, 2018, http://www.chicagobusiness.com/article/20180214/BLOGS02/180219947/rauners-plan-trim-income-tax-push-costs-to-local-governments.

[10] Tim Jones and Kiannah Sepeda-Miller, “Tax Overhaul Sideshow: Long on Gimmicks, Short on Solutions,” Crain’s Chicago Business, Feb. 21, 2018, http://www.chicagobusiness.com/article/20180221/NEWS02/180229987.

[11] “J.B. Pritzker Candidate Profile,” Belleville (IL) News-Democrat, Feb. 21, 2018, http://www.bnd.com/news/politics-government/election/article201174139.html.

[12] “Candidate Questionnaire: Christopher Kennedy,” The (Springfield, IL) State Journal-Register, Feb. 25, 2018, http://www.sj-r.com/opinion/20180225/candidate-questionnaire-christopher-kennedy.

[13] Rebecca Susmarki, “Daiber Talks Plans for Illinois,” Daily Review Atlas (Monmouth, IL), Feb. 22, 2018, http://www.reviewatlas.com/news/20180222/daiber-talks-plans-for-illinois.

[14] Marni Pyke, “Biss: Illinois Suffocating Under Too Many Pension Systems,” Daily Herald (Arlington Heights, IL), Jan. 10, 2018, http://www.dailyherald.com/news/20180109/biss-illinois-suffocating-under-too-many-pension-systems.

[15] 100th Ill. Gen. Assem., House Bill 3522, 2018 Sess.

[16] Id.

[17] Morgan Scarboro, “State Individual Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2017,” Tax Foundation, March 9, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/state-individual-income-tax-rates-brackets-2017/.

[18] Matthew DeFour, “Republicans Want Income Tax Rate Cut Paid for with Tax Code Tweaks,” Wisconsin State Journal, Feb. 17, 2018, http://host.madison.com/wsj/news/local/govt-and-politics/republicans-want-income-tax-rate-cut-paid-for-with-tax/article_707af494-0a17-5b36-b432-bdfa291fa420.html.

[19] Matthew DeFour and Mark Sommerhauser, “Assembly GOP Plan Overhaul[s] Fuel Taxes, Steers State Toward Flat Income Tax,” Wisconsin State Journal, May 5, 2017, http://host.madison.com/wsj/news/local/govt-and-politics/assembly-gop-plan-overhaul-fuel-taxes-steers-state-toward-flat/article_df69d534-f6bc-56e3-8f71-046387d771c1.html.

[20] Id.

[21] The highest rate imposed on a marginal dollar of taxable income in Iowa is about 7.0 percent, for income subject to the state’s top marginal rate and the 22 percent federal rate.

[22] 100th Ill. Gen. Assem., House Bill 3522, 2018 Sess.

[23] Ill. Const. 1970, art. IX, § 3.

[24] 99th Ill. Gen. Assem., Senate Joint Resolution Constitutional Amendment 1, 2016 Sess. State Senator Daniel Bliss was a Senate cosponsor of the amendment.

[25] Jens Arnold, Bert Brys, Christopher Heady, Heady, Åsa Johansson, Cyrille Schwellnus, and Laura Vartia, “Tax Policy for Economic Recovery and Growth,” The Economic Journal 121:550 (February 2011).

[26] John Mullen and Martin Williams, “Marginal Tax Rates and State Economic Growth,” Regional Science and Urban Economics 24:6 (December 1994).

[27] Small firms were responsible for 47.2 percent of all state employment in 2012, though not all small businesses are pass-through entities. See U.S. Small Business Administration, “Small Business Profiles for the States and Territories,” February 2015: 57-60, https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/advocacy/SB%20Profiles%202014-15_0.pdf.

[28] Such a policy is not even particularly progressive. The size of a business tells us little about the incomes of its owners and investors, and the concept of ability to pay is rendered moot because corporate income taxes are imposed on net income.

[29] Morgan Scarboro, “State Corporate Income Tax Rates and Brackets for 2018,” Feb. 7, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/state-corporate-income-tax-rates-brackets-2018/.

[30] Benjamin Yount, “Tax Increase, Impact, Dominate Illinois Capitol in 2011,” Illinois Statehouse News, Dec. 27, 2011.

[31] See generally, Jared Walczak, “Ohio’s Commercial Activity Tax: A Reappraisal,” Sept. 26, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/ohio-commercial-activity-tax-2017/.

Share this article